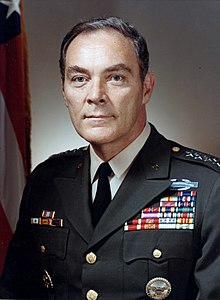

Alexander Haig

Alexander Meigs Haig Jr. (/heɪɡ/; 2 December 1924 – 20 February 2010) was United States Secretary of State under president Ronald Reagan and White House chief of staff under presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford.[1] Prior to and in between these cabinet-level positions, he was a general in the U.S. Army, serving first as the vice chief of staff of the Army and then as Supreme Allied Commander Europe. In 1973, Haig became the youngest four-star general in the Army's history.

Haig was born and raised in Pennsylvania. He graduated from the U.S. Military Academy and served in the Korean War, during which he served as an aide to general Alonzo Patrick Fox and general Edward Almond. Afterward, he served as an aide to defense secretary Robert McNamara. During the Vietnam War, Haig commanded a battalion and later a brigade of the 1st Infantry Division. For his service, Haig received the Distinguished Service Cross, the Silver Star with oak leaf cluster, and the Purple Heart.[2]

In 1969, Haig became an assistant to national security advisor Henry Kissinger. He became vice chief of staff of the Army, the Army's second-highest-ranking position, in 1972. After the 1973 resignation of H. R. Haldeman, Haig became President Nixon's chief of staff. Serving in the wake of the Watergate scandal, he became especially influential in the final months of Nixon's tenure, playing a role in persuading Nixon to resign in 1974. Haig continued to serve as chief of staff for the first month of President Ford's tenure. From 1974 to 1979, Haig served as Supreme Allied Commander Europe, commanding all NATO forces in Europe. He retired from the army in 1979 and pursued a career in business.

After Reagan won the 1980 U.S. presidential election, he nominated Haig to be his secretary of state. After the Reagan assassination attempt, Haig said "I am in control here, in the White House", despite not being next in the line of succession. During the Falklands War, Haig sought to broker peace between the United Kingdom and Argentina. He resigned from Reagan's cabinet in July 1982. He unsuccessfully sought the presidential nomination in the 1988 Republican primaries. He also served as the head of a consulting firm and hosted the television program World Business Review.[3]

Early life and education

[edit]Haig was born in Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania, the middle of three children of Alexander Meigs Haig, a Republican lawyer of Scottish descent, and his wife, Regina Anne (née Murphy).[4] When Haig was 9, his father, aged 41, died of cancer. His Irish American mother raised her children in the Catholic faith.[5] Haig initially attended Saint Joseph's Preparatory School in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on a scholarship; when he was withdrawn due to poor academic performance, he transferred to Lower Merion High School in Ardmore, Pennsylvania, where he graduated in 1942.

Initially unable to secure his desired appointment to the United States Military Academy, though one of his teachers opined that "Al is definitely not West Point material", Haig studied at the University of Notre Dame, where he earned a "string of A's" in an "intellectual awakening"[6] for two years before securing a congressional appointment to the U.S. Military Academy in 1944 at the behest of his uncle, who served as the Philadelphia municipal government's director of public works.[6]

Haig was enrolled in an accelerated wartime curriculum at West Point that deemphasized the humanities and social sciences, and he graduated in the bottom third of his class[7] (ranked 214 of 310) in 1947.[8] Although a West Point superintendent characterized Haig as "the last man in his class anyone expected to become the first general",[9] other classmates acknowledged his "strong convictions and even stronger ambitions".[8] Haig later earned an MBA from the Columbia Business School in New York City in 1955. As a major, he attended the Naval War College in 1960 and then earned a M.A. in international relations from Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. in 1961. His thesis at Georgetown University examined the role of military officers in making national policy.

Early military career

[edit]Korean War

[edit]As a young officer, Haig served as an aide to Lieutenant General Alonzo Patrick Fox, a deputy chief of staff to General Douglas MacArthur. In 1950 Haig married Fox's daughter, Patricia.[7] In the early days of the Korean War, Haig was responsible for maintaining General MacArthur's situation map and briefing MacArthur each evening on the day's battlefield events.[10] Haig later served (1950–51) with the X Corps, as aide to MacArthur's chief of staff, General Edward Almond,[2] who awarded Haig two Silver Stars and a Bronze Star with Valor device.[11] Haig participated in four Korean War campaigns, including the Battle of Inchon, the Battle of Chosin Reservoir and the evacuation of Hŭngnam,[10] as Almond's aide.

Pentagon assignments

[edit]Haig served as a staff officer in the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations at the Pentagon (1962–64), and then was appointed military assistant to Secretary of the Army Stephen Ailes in 1964. He then was appointed military assistant to Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, continuing in that service until the end of 1965.[7] In 1966, Haig graduated from the United States Army War College.

Vietnam War

[edit]

In 1966, Haig took command of a battalion of the 1st Infantry Division during the Vietnam War. On 22 May 1967, General William Westmoreland rewarded Haig with the Distinguished Service Cross, the U.S. Army's second-highest medal for valor, in recognition of his actions during the Battle of Ap Gu in March 1967.[12] During the battle, Haig, then a member of the 1st Battalion, 26th Infantry Regiment, became pinned down by a Viet Cong force that outnumbered U.S. forces by three to one. In an attempt to survey the battlefield, Haig boarded a helicopter and flew to the point of contact. His helicopter was subsequently shot down, leading to two days of bloody hand-to-hand combat. An excerpt from Haig's Distinguished Service Cross citation states:

When two of his companies were engaged by a large hostile force, Colonel Haig landed amid a hail of fire, personally took charge of the units, called for artillery and air fire support and succeeded in soundly defeating the insurgent force ... the next day a barrage of 400 rounds was fired by the Viet Cong, but it was ineffective because of the warning and preparations by Colonel Haig. As the barrage subsided, a force three times larger than his began a series of human wave assaults on the camp. Heedless of the danger himself, Colonel Haig repeatedly braved intense hostile fire to survey the battlefield. His personal courage and determination, and his skillful employment of every defense and support tactic possible, inspired his men to fight with previously unimagined power. Although his force was outnumbered three to one, Colonel Haig succeeded in inflicting 592 casualties on the Viet Cong ... HQ US Army, Vietnam, General Orders No. 2318 (22 May 1967)[13]

Haig was also awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Purple Heart during his tour in Vietnam[12] and was eventually promoted to colonel as commander of 2nd Brigade, 1st Infantry Division in Vietnam.

Return to West Point

[edit]Following his one-year tour of Vietnam during the Vietnam War, Haig returned to the United States to become regimental commander of the Third Regiment of the Corps of Cadets at West Point under the newly appointed commandant, Brigadier General Bernard W. Rogers. Both had previously served together in the 1st Infantry Division, Rogers as assistant division commander and Haig as brigade commander.

Security adviser and vice chief of staff (1969–1973)

[edit]In 1969, he was appointed military assistant to the assistant to the president for national security affairs, Henry Kissinger. A year later, he replaced Richard V. Allen as deputy assistant to the president for national security affairs. During this period, he was promoted to brigadier general (September 1969) and major general (March 1972).

In the spring of 1972, the North Vietnamese armed forces (PAVN) launched a multi-prong attack, known as the Easter Offensive, on every region of South Vietnam. For the first time, the PAVN deployed heavy weaponry such as mobile surface-to-air missile batteries, tanks, and armored vehicles. In the early weeks of the offensive, the PAVN won startling advances, and captured crucial bases, roads, and cities. Nixon and Kissinger——while delicately picking their way through the diplomatic thickets of détente with Moscow and open relations with Peking (Beijing)——decided to respond to North Vietnam’s sweeping assault by mining its principal harbor, and massively bombing targets in every quarter of North Vietnam.[14] Nixon, in his reflexive suspicion,[15] and Kissinger, in his boundless ambition,[16] opted to bypass the Departments of State and Defense, as well as the Joint Chiefs of Staff(JCS), in any advisory or decision-making capacity relating to what would become known as Operation Linebacker.[17]

Haig effectively substituted for the JCS during this time. He developed the core strategy coordinating the mining with the bombing of transportation targets. He was dispatched, to the Pentagon as well as Saigon, to critique field commanders and military procedure, and provide an independent information channel to the White House. He was a member of a national security triumvirate, along with Nixon and Kissinger, that both scapegoated and ignored the military command running the daily operations in Vietnam.[18]

In this position, Haig helped South Vietnamese president Nguyen Van Thieu negotiate the final cease-fire talks in 1972. Haig continued in the role until 4 January 1973,[19] when he became vice chief of staff of the Army. Nixon planned to appoint Haig as chief of staff over Creighton Abrams, whom he personally disliked, but secretary of defense Melvin Laird resisted as Haig lacked the relevant upper-level command experience.[20] He was confirmed by the U.S. Senate in October 1972, thus skipping the rank of lieutenant general. By appointing him to this billet, Nixon "passed over 240 generals" who were senior to Haig.[21]

White House Chief of Staff (1973–1974)

[edit]Nixon administration

[edit]

In May 1973, after only four months as VCSA, Haig returned to the Nixon administration at the height of the Watergate affair as White House Chief of Staff. During the Saturday Night Massacre, Haig attempted to make acting-Attorney General William Ruckelshaus to fire special prosecutor Archibald Cox. Haig's coercion failed, and Ruckelshaus resigned.[22] Retaining his Army commission, he remained in the position until 21 September 1974, ultimately overseeing the transition to the presidency of Gerald Ford following Nixon's resignation on 9 August 1974.

Haig has been largely credited with keeping the government running while President Nixon was preoccupied with Watergate[23] and was essentially seen as the "acting president" during Nixon's last few months in office.[7] During July and early August 1974, Haig played an instrumental role in persuading Nixon to resign. Haig presented several pardon options to Ford a few days before Nixon resigned. In this regard, in his 1999 book Shadow, author Bob Woodward describes Haig's role as the point man between Nixon and Ford during the final days of Nixon's presidency. According to Woodward, Haig played a major behind-the-scenes role in the delicate negotiations of the transfer of power from Nixon to Ford.[24] Indeed, about one month after taking office, Ford did pardon Nixon, resulting in much controversy.

However, Haig denied the allegation that he played a key role in arbitrating Nixon's resignation by offering Ford's pardon to Nixon. One of the most crucial moments occurred a day before Haig's departure to Europe to begin his tenure as NATO Supreme Allied Commander. Haig was telephoned by J. Fred Buzhardt, who once served as special White House counsel for Watergate matters.[25][26] In the call, Buzhardt discussed with Haig President Ford's upcoming speech to the nation about pardoning Nixon, informing Haig that the speech contained something indicating Haig's role in Nixon's resignation and Ford's pardon of Nixon. According to Haig's autobiography (Inner Circles: How America Changed the World), Haig was furious and immediately drove straight to the White House to determine the veracity of Buzhardt's claims. This was due to his concern that Ford's speech would expose Haig's role in negotiating Nixon's resignation supposedly in exchange for a pardon issued by the new president.[25][26]

On 7 August 1974, two days before Nixon's resignation, Haig met with Nixon in the Oval Office to discuss the transition. Following their conversation, Nixon told Haig "You fellows, in your business, have a way of handling problems like this. Give them a pistol and leave the room. I don't have a pistol, Al."[27]

Ford administration

[edit]

Following Nixon's resignation, Haig remained briefly as White House Chief of Staff under Ford. Haig aided in the transition by advising the new president mostly on policy matters on which he had been working under the Nixon presidency and introducing Ford to the White House staff and their daily activities. Haig recommended that Ford retain several of Nixon's White House staff for 30 days to provide an orderly transition. Haig and Kissinger also advised Ford on Nixon's détente policy with the Soviet Union following the SALT I treaty in 1972.

Haig found it difficult to get along with the new administration and wanted to return to the Army for his last command. It had also been rumored that Ford wanted to be his own chief of staff. At first Ford decided to replace Haig with Robert T. Hartmann, Ford's chief of staff during his tenure as vice president.[26][25][28] Ford soon replaced Hartmann with United States Permanent Ambassador to NATO Donald Rumsfeld. Author and Haig biographer Roger Morris, a former colleague of Haig's on the National Security Council early in Nixon's first term, wrote that when Ford pardoned Nixon, he in effect pardoned Haig as well.[29]

Haig resigned from his position as White House Chief of Staff and returned to active duty in the United States Army in September 1974.[25]

NATO Supreme Allied Commander (1974–1979)

[edit]

In December 1974, Haig was appointed as the next Supreme Allied Commander Europe by President Ford, replacing General Andrew Goodpaster and returning to active duty in the United States Army. Haig also became the front-runner to be the 27th U.S. Army Chief of Staff, following the death of General Creighton Abrams from complications of surgery to remove lung cancer on 4 September 1974. However it was General Frederick C. Weyand who ultimately filled Abrams's position as Chief of Staff.[25] From 1974 to 1979 Haig served as the Supreme Allied Commander Europe, the commander of NATO forces in Europe, as well as commander-in-chief of United States European Command. During his tenure as SACEUR, Haig focused on transforming SACEUR in order to face the future global challenge following the end of the Vietnam War and the rise of Soviet influence within Eastern Europe.

Haig focused on strengthening the relationship between the United States and NATO member nations and their allies. As a result, several fleets of United States Air Force aircraft, such as the F-111 Aardvark from the Strategic Air Command, were relocated to US Air Force bases located in Europe.[25] Haig also stressed the importance of increasing the training of US troops deployed in Europe following his tour of the Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean Sea, on which Haig saw poorly-disciplined and ill-trained troops. As a result, Haig conducted routine inspections during NATO troops' training and often went to the training site and participated in the training itself. Haig also recommended the revitalization of equipment in the US installations in Europe and US troops deployed in Europe, in order to strengthen deterrence from possible attack.[25]

Haig took the same route to SHAPE every day—a pattern of behavior that did not go unnoticed by terrorist organizations. On 25 June 1979, Haig was the target of an assassination attempt in Mons, Belgium. A land mine blew up under the bridge on which Haig's car was traveling, narrowly missing his car and wounding three of his bodyguards in a following car.[30][31] Authorities later attributed responsibility for the attack to the Red Army Faction (RAF). In 1993 a German court sentenced Rolf Clemens Wagner, a former RAF member, to life imprisonment for the assassination attempt.[30] During Haig's last month as Supreme Allied Commander Europe, he oversaw the talks and negotiation between the United States and NATO member nations of a new policy following the signing of SALT II treaty on 18 June 1979, by President Jimmy Carter and Soviet President Leonid Brezhnev. However Haig also drew concern regarding the treaty, which he believed benefited the Soviet position by giving them a way to build up their military arsenal.[25]

Haig retired from his position as Supreme Allied Commander Europe in July 1979 and was succeeded by General Bernard W. Rogers, who previously served as Army Chief of Staff.[25] Haig's retirement ceremony took place at NATO Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe on 1 July 1979, and was attended by Secretary of Defense Harold Brown, NATO Secretary General Joseph Luns and U.S. Ambassador to NATO William Tapley Bennett Jr.[25]

Civilian positions

[edit]In 1979, Haig joined the Philadelphia-based Foreign Policy Research Institute as director of its Western Security Program, and he later served on the organization's board of trustees.[32] Later that year, he was named president and director of United Technologies Corporation under chief executive officer Harry J. Gray, where he remained until 1981.

Secretary of State (1981–1982)

[edit]

Haig was the second of three career military officers to become secretary of state (George C. Marshall and Colin Powell were the others). His speeches in this role in particular led to the coining of the neologism "Haigspeak," described in a dictionary of neologisms as "Language characterized by pompous obscurity resulting from redundancy, the semantically strained use of words, and verbosity,"[33] leading Ambassador Nicko Henderson to offer a prize for the best rendering of the Gettysburg Address in Haigspeak.[34]

Initial challenges

[edit]On 11 December 1980, president-elect Reagan was prepared to publicly announce nearly all of his candidates for the most important cabinet-level posts. Singularly absent from the list of top nominees was his choice for Secretary of State, presumed by many at the time to be Alexander Haig. Haig's prospects for Senate confirmation were clouded when Senate Democrats questioned his role in the Watergate scandal. In Haig's defense, North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms claimed to have phoned former president Nixon personally to inquire whether any material on Nixon's unreleased White House tapes could embarrass Haig. According to Helms, Nixon replied, "Not a thing."[35] Haig was eventually confirmed after hearings he described as an "ordeal," during which he received no encouragement from Reagan or his staff.[36]

Several days earlier, on 2 December 1980, as Haig faced these initial challenges to the next step in his political career, four U.S. Catholic missionary women in El Salvador, two of whom were Maryknoll sisters, were beaten, raped and murdered by five Salvadoran national guardsmen ordered to follow them. Their bodies were exhumed from a remote shallow grave two days later in the presence of then-U.S. ambassador to El Salvador Robert E. White. Despite this diplomatically awkward atrocity, the Carter administration soon approved $5.9 million in lethal military assistance to El Salvador's oppressive right-wing government.[37] The incoming Reagan administration expanded that aid to $25 million less than six weeks later.[38]

In justifying the arms shipments, the new administration claimed that the Salvadoran government of José Napoleón Duarte had taken "positive steps" to investigate the murder of four American nuns, but this was disputed by U.S. Ambassador Robert E. White, who said that he could find no evidence the junta was "conducting a serious investigation." White was dismissed from the Foreign Service by Haig because of his complaints. White later asserted that the Reagan administration was determined to ignore and even conceal the complicity of the Salvadoran government and army in the murders.[39]

Throughout the 1980 U.S. presidential campaign, Reagan and his foreign policy advisers faulted the Carter administration's perceived over-emphasis on the human rights abuses committed by authoritarian governments allied to the U.S., labeling it a "double standard" when compared with Carter's treatment of communist-bloc governments. Haig, who described himself as the "vicar" of U.S. foreign policy,[40] believed the human rights violations of a U.S. ally such as El Salvador should be given less attention than the ally's successes against enemies of the U.S., and thus found himself diminishing the murders of the nuns before the House Foreign Affairs Committee in March 1981:

I'd like to suggest to you that some of the investigations would lead one to believe that perhaps the vehicle the nuns were riding in may have tried to run through a roadblock, or may have accidentally been perceived to have been doing so, and there may have been an exchange of fire, and then perhaps those who inflicted the casualties sought to cover it up.

— Alexander Haig, Alexander Haig, House Foreign Affairs committee testimony, quoted by UPI, 19 March 1981[41]

The outcry that immediately followed Haig's insinuation prompted him to emphatically withdraw his speculative suggestions the very next day before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.[42] Similar public relations miscalculations, by Haig and others, continued to plague the Reagan administration's attempts to build popular support at home for its Central American policies.

Reagan assassination attempt

[edit]

In 1981, following the 30 March assassination attempt on Reagan, Haig asserted before reporters, "I am in control here"[43] as a result of Reagan's hospitalization, indicating that, while Reagan had not "transfer[red] the helm," Haig was in fact directing White House crisis management until Vice President George Bush arrived in Washington to assume that role.

Constitutionally, gentlemen, you have the president, the vice president, and the secretary of state in that order, and should the president decide he wants to transfer the helm to the vice president, he will do so. He has not done that. As of now, I am in control here, in the White House, pending return of the vice president and in close touch with him. If something came up, I would check with him, of course.

The U.S. Constitution, including both the presidential line of succession and the 25th Amendment, dictates what happens when a president is incapacitated. The Speaker of the House (at the time, Tip O'Neill, Democrat) and the president pro tempore of the Senate (at the time, Strom Thurmond, Republican), precede the secretary of state in the line of succession. Haig later clarified,

I wasn't talking about transition. I was talking about the executive branch, who is running the government. That was the question asked. It was not, "Who is in line should the president die?"

— Alexander Haig, "Alexander Haig" interview with 60 Minutes II 23 April 2001

His reputation never recovered after this press conference,[45] and in virtually all of the obituaries published after his death, his quote is referenced in the opening paragraphs.

Falklands War

[edit]

In April 1982, Haig conducted shuttle diplomacy between the governments of Argentina in Buenos Aires and the United Kingdom in London after Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands. Negotiations collapsed and Haig returned to Washington on 19 April. The British naval fleet then entered the war zone. In December 2012 documents released under the United Kingdom's 30 Year Rule disclosed that Haig planned to reveal British classified military information to Argentina in advance of the recapture of South Georgia Island. The information, which contained the plans for Operation Paraquet, was intended to show the Argentine military junta in Buenos Aires that the United States was a neutral player and could be trusted to act impartially during negotiations to end the conflict.[46] However, in 2012 it was revealed via documents released from the Reagan Presidential Library that Haig attempted to persuade Reagan to side with Argentina in the war.[47]

1982 Lebanon War

[edit]Haig's report to Reagan on 30 January 1982, shows that Haig feared the Israelis might start a war against Lebanon.[48] Critics accused Haig of "greenlighting" the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in June 1982. Haig denied this and said he urged restraint.[49]

Resignation

[edit]Haig caused some alarm with his suggestion that a "nuclear warning shot" in Europe might be effective in deterring the Soviet Union.[50] His tenure as secretary of state was often characterized by his clashes with the defense secretary, Caspar Weinberger. Haig, who repeatedly had difficulty with various members of the Reagan administration during his year-and-a-half in office, decided to resign his post on 25 June 1982.[51] President Reagan accepted his resignation on 5 July.[52] Haig was succeeded by George P. Shultz, who was confirmed on July 16.[53]

1988 Republican presidential primaries

[edit]Haig ran unsuccessfully for the 1988 Republican Party presidential nomination. Although he enjoyed relatively high name recognition, Haig never broke out of single digits in national public opinion polls. He was a fierce critic of then–Vice President George H. W. Bush, often doubting Bush's leadership abilities, questioning his role in the Iran–Contra affair, and using the word "wimp" in relation to Bush in an October 1987 debate in Texas.[54] Despite extensive personal campaigning and paid advertising in New Hampshire, Haig remained stuck in last place in the polls. After finishing with less than 1 percent of the vote in the Iowa caucuses and trailing badly in the New Hampshire primary polls, Haig withdrew his candidacy and endorsed Senator Bob Dole.[55][56] Dole, steadily gaining on Bush after beating him handily a week earlier in the Iowa caucus, ended up losing to Bush in the New Hampshire primary by 10 percentage points. With his momentum regained, Bush easily won the nomination.

Later life, health, and death

[edit]

In 1980 Haig had a double heart bypass operation.[57]

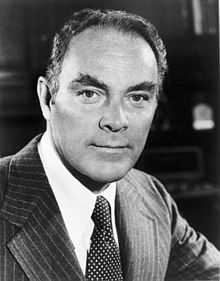

After leaving the Reagan White House, Haig took a seat on the MGM board of directors in an effort to cultivate a film career.[58] He supervised the development of John Milius' Red Dawn (1984) and made significant changes to it.[59] While heading a consulting firm in the 1980s and 1990s, he served as a director for various struggling businesses, including computer manufacturer Commodore International.[60] He also served as a founding corporate director of America Online.[61]

Haig was the host for several years of the television program World Business Review. At the time of his death, he was the host of 21st Century Business, with each program a weekly business education forum that included business solutions, expert interview, commentary, and field reports.[62] Haig was co-chairman of the American Committee for Peace in the Caucasus, along with Zbigniew Brzezinski and Stephen J. Solarz. He was also member of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy (WINEP) board of advisers.[63]

On 5 January 2006, Haig participated in a meeting at the White House of former secretaries of defense and state to discuss U.S. foreign policy with Bush administration officials.[64] On 12 May 2006, Haig participated in a second White House meeting with 10 former secretaries of state and defense. The meeting included briefings by Donald Rumsfeld and Condoleezza Rice and was followed by a discussion with President George W. Bush.[65] Haig's memoirs—Inner Circles: How America Changed The World—were published in 1992.

On 19 February 2010, a hospital spokesman revealed that the 85-year-old Haig had been hospitalized at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore since January 28 and remained in critical condition.[66] On February 20, Haig died at the age of 85, from complications from a staphylococcal infection that he had prior to admission. According to The New York Times, his brother, Frank Haig, said the Army was coordinating a mass at Fort Myer in Washington, D.C., and an interment at Arlington National Cemetery, but both had to be delayed by about two weeks owing to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.[7] A Mass of Christian Burial was held at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C., on 2 March 2010. Eulogies were given by Henry Kissinger and Sherwood D. Goldberg.[67]

President Barack Obama said in a statement that "General Haig exemplified our finest warrior–diplomat tradition of those who dedicate their lives to public service."[7] Secretary of State Hillary Clinton described Haig as a man who "served his country in many capacities for many years, earning honor on the battlefield, the confidence of presidents and prime ministers, and the thanks of a grateful nation."[68]

Family

[edit]Alexander Haig was married to Patricia (née Fox), with whom he had three children: Alexander Patrick Haig, Barbara Haig, and Brian Haig.[7] Haig's younger brother, Frank Haig, was a Jesuit priest and professor emeritus of physics at Loyola University in Baltimore, Maryland.[69]

Publications

[edit]Articles

- "Introduction". World Affairs, Vol. 144, No. 4, Statements by Ambassador Max Kampelman before the Madrid Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, Spring 1982. JSTOR 20671913 (pp. 299–301)

- "Stalemate: The Public Reaction to Poland". World Affairs, Vol. 144, No. 4, Statements by Ambassador Max Kampelman before the Madrid Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, Spring 1982. JSTOR 20671920 (pp. 467–511)

- "U.S. Foreign Policy: A Discussion with Former Secretaries of State Dean Rusk, William P. Rogers, Cyrus R. Vance, and Alexander M. Haig, Jr.". International Studies Notes, Vol. 11, No. 1, Special Edition: The Secretaries of State, Fall 1984. JSTOR 44234902 (pp. 10–20)

- "Reply". Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs, Vol. 27, No. 2, Summer 1985. doi:10.2307/165716 JSTOR 165716 (pp. 23–24)

- "The Challenges to American Leadership". Harvard International Review, Vol. 11, No. 3, Tenth Anniversary Issue – American Foreign Policy: Toward the 1990s, 1989. JSTOR 43648931 (pp. 24–29)

- "Nation Building: A Flawed Approach". The Brown Journal of World Affairs, Vol. 2, No. 1, Winter 1994. JSTOR 24595446 (pp. 7–10)

Books

- Caveat: Realism, Reagan and Foreign Affairs. New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1984. ISBN 978-0025473706. 367 pages.

- Inner Circles: How America Changed the World: A Memoir. New York, NY: Warner Books, 1992. ISBN 978-0446515719 LCCN 91-50409. 650 pages.

Contributed works

- "Foreword". Soviet Leaders from Lenin to Gorbachev by Thomas Streissguth. Minneapolis, MN: Oliver Press, 1992. ISBN 978-1881508021 LCCN 92-19903 (pp. 7–8)

Awards and decorations

[edit]

| ||

| Valorous Unit Award | ||

| Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation | Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross Unit Citation | Republic of Vietnam Civil Actions Medal Unit Citation |

|

| SHAPE Badge |

Other honors

[edit]In 1976, Haig received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[71] In 2009, Haig was recognized for their generous gift in support of academic programs at West Point by being inducted into the Eisenhower Society for Lifetime Giving.[72]

References

[edit]- ^ "Alexander Haig - MSN Encarta". MSN. 10 March 2008. Archived from the original on 10 March 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2025.

- ^ a b "Premier Speakers Bureau". Archived from the original on 14 January 2010.

- ^ "World Business Review (TV Series 1996–2006)", IMDb, retrieved 20 October 2020

- ^ Hohmann, James (February 21, 2010). "Alexander Haig, 85; soldier-statesman managed Nixon resignation". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ "Haig's Future Uncertain After a Shaky Start". Anchorage Daily News. 11 April 1981. Retrieved 22 December 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Bellow, Adam (13 July 2004). In Praise of Nepotism. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. ISBN 9781400079025.

- ^ a b c d e f g Weiner, Tim (February 20, 2010). "Alexander M. Haig Jr., 85, Forceful Aide to 2 Presidents, Dies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 23, 2010. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ^ a b Jackson, Harold (20 February 2010). "Alexander Haig obituary". The Guardian.

- ^ "Al Haig, the long goodbye". 22 February 2010.

- ^ a b Alexander M. Haig Jr. "Lessons of the forgotten war".

- ^ "UT Biography". Archived from the original on 11 May 2013.

- ^ a b "West Point Citation". Archived from the original on 16 May 2006.[verification needed]

- ^ "Full Text Citations For Award of The Distinguished Service Cross, US Army Recipients – Vietnam".

- ^ Randolph, Stephen (2007). Powerful and Brutal Weapons: Nixon, Kissinger, and the Easter Offensive. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674024915.

- ^ Summers, Anthony (2000). The Arrogance of Power: The Secret World of Richard Nixon. New York: Viking.

- ^ Hersh, Seymour (1983). The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House. New York: Summit.

- ^ Randolph 2007, p. 164.

- ^ Randolph 2007, p. 87-88.

- ^ "Personnel - White House Appointment of Military Personnel to Staff" (PDF). Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library & Museum. p. 11.

- ^ Colodny, Len; Shachtman, Tom (2009). Forty Years War. TrineDay. ISBN 9781634240574.

- ^ "4-Star Diplomat in White House Alexander Meigs Haig Jr". The New York Times. 5 May 1973.

- ^ Frank, Jeffrey (9 May 2017). "Comey's Firing Is—and Isn't—Like Nixon's Saturday Night Massacre". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ "Alexander Haig". MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on March 10, 2008.

- ^ The Final Days, by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, 1976, New York, Simon & Schuster; Shadow, by Bob Woodward, 1999, New York, Simon Schuster, pp. 4–38.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Haig, Alexander M. (1 September 1992). Inner Circles: How America Changed the World: A Memoir. Grand Central Publisher. ISBN 978-0446515719.

- ^ a b c Woodward, Robert Upshur (16 June 1999). Shadow: Five Presidents And The Legacy Of Watergate. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0684852638.

- ^ Woodward, Bob (1976). The final days. Carl Bernstein. New York. ISBN 0-671-22298-8. OCLC 1975233.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Rumsfeld, Donald (2011). Known and unknown : a memoir. New York: Sentinel. ISBN 978-1-59523-067-6. OCLC 650210649.

- ^ Haig: The General's Progress, by Roger Morris (American writer), Playboy Press, 1982, pp. 320–25.

- ^ a b "German Guilty in '79 Attack At NATO on Alexander Haig". The New York Times. 25 November 1993.

- ^ Aust, Stefan (2020). Der Baader-Meinhof-Komplex (in German). Piper. p. 959. ISBN 978-3-492-23628-7.

- ^ Maykuth, Andrew (21 February 2010). "Philadelphia dominated Haig's formative years". Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ^ Fifty years among the new words: a dictionary of neologisms, 1941–1991, John Algeo, p.231

- ^ Financial Times, London, March 21, 2009

- ^ "Reagan selects half of Cabinet-level staff". Gadsden Times. Associated Press. 11 December 1980.

- ^ Chace, James (22 April 1984). "The Turbulent Tenure of Alexander Haig". The New York Times.

- ^ LeoGrande, William (1998). Our Own Backyard: The United States in Central America, 1977–1992. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 70. ISBN 0807898805.

- ^ LeoGrande 1998, p. 89.

- ^ Bonner, Raymond (November 9, 2014). "Bringing El Salvador Nun Killers to Justice". The Daily Beast. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

- ^ "Alexander Haig". The Economist. 25 February 2010.

- ^ "Church Women Ran Roadblock, Haig Theorizes". Pittsburgh Press. UPI. 19 March 1981. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ Michaels, Leonard; Ricks, Christopher (1990). The State of the Language (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 261. ISBN 0520059069.

- ^ "The 'anonymous official op-ed' is less than it seems". 6 September 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ^ "Alexander Haig". Time. 2 April 1984. p. 22 of 24 page article. Archived from the original on 6 April 2008. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- ^ Inboden, William (2022). The Peacemaker: Ronald Reagan, the Cold War, and the World on the Brink. Dutton. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-1-5247-4589-9.

- ^ Tweedie, Neil (28 December 2012). "US wanted to warn Argentina about South Georgia". Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ^ O'Sullivan, John (2 April 2012). "How the U.S. Almost Betrayed Britain". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- ^ Ronald Reagan edited by Douglas Brinkley (2007) The Reagan Diaries Harper Collins ISBN 978-0-06-087600-5 p. 66 Saturday, January 30

- ^ "Alexander Haig". Time. 9 April 1984. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009.

- ^ Waller, Douglas C. Congress and the Nuclear Freeze: An Inside Look at the Politics of a Mass Movement, 1987. Page 19.

- ^ 1982 Year in Review: Alexander Haig Resigns

- ^ Ajemian, Robert; George J. Church; Douglas Brew (5 July 1982). "The Shakeup at State". Time. Archived from the original on 27 March 2010. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ^ Short History of the Department of State, United States Department of State, Office of the Historian. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ^ Dowd, Maureen (21 November 1987). "Haig, the Old Warrior, in New Battles". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ "Haig Calls Meeting to Discuss Campaign". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. 12 February 1988. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ Clifford, Frank (13 February 1988). "Haig Drops Out of GOP Race, Endorses Dole". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ Harold Jackson (20 February 2010). "obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ^ Bart, Peter (28 September 2009). "First Look: Famous Firings a Tough Ax to Follow". Variety.

- ^ Bart, Peter (16 June 1997). "'Red Dawn': Shooting it the McVeigh way". Variety.

- ^ "Businessweek June 16, 1991". Businessweek.com. 16 June 1991. Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ^ "New Atlanticist". Acus.org. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ^ "World Business Review with Alexander Haig". Archived from the original on 25 October 2006. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ^ "Business Wire AOL-Time Warner announces its board of directors". Business Wire. 12 January 2001. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ^ "President George W. Bush poses for a photo Thursday, January 5, 2006, in the Oval Office with former secretaries of state and secretaries of defense from both Republican and Democratic administrations, following a meeting on the strategy for victory in Iraq". The White House. 5 January 2006. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ^ "Bush discusses Iraq with former officials".

- ^ "Haig, top adviser to 3 presidents, hospitalized". Associated Press. 19 February 2010. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- ^ "Alexander M. Haig, Jr". West Point Association of Graduates. Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved August 9, 2011.

- ^ "Alexander Haig, former secretary of state, dies at 85". Washington Times. 20 February 2010. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ^ Krebs, Albin (25 January 1982). "NOTES ON PEOPLE; A Haig Inaugurated". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ^ "Cidadãos Estrangeiros Agraciados com Ordens Portuguesas". Página Oficial das Ordens Honoríficas Portuguesas. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "The Dedication of the Alexander M. Haig, Jr. Room". West Point.

Further reading

[edit]- Colodny, Len and Robert Gettlin. Silent Coup: The Removal of a President. New York City: St. Martin's Press, 1991.

- Haig, Alexander. Caveat: Realism, Reagan and Foreign Affairs. New York City: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1984.

- Haig, Alexander and Charles McCarry. Inner Circles: How America Changed the World. Grand Central Publishing, 2 January 1994.

- Hersh, Seymour. The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House. New York City: Summit Books, 1983. ISBN 0-671-50688-9

- Morris, Robert. Haig: The General's Progress. ISBN 0872237532 LCCN 81-82835. 490 pages.

External links

[edit]- The Day Reagan was Shot article on Haig

- The Falklands: Failure of a Mission critique of Haig's mediation efforts

- Portrait of Alexander Haig by Margaret Holland Sargent

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Alexander Haig at IMDb

- ANC Explorer

- 1924 births

- 2010 deaths

- 20th-century American memoirists

- AOL people

- American corporate directors

- American people of Irish descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- Candidates in the 1988 United States presidential election

- Columbia Business School alumni

- Deaths from staphylococcal infection

- Ford administration personnel

- Georgetown University alumni

- Grand Crosses 1st class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Hudson Institute

- Infectious disease deaths in Maryland

- Knights of Malta

- Lower Merion High School alumni

- Military personnel from Philadelphia

- NATO Supreme Allied Commanders

- Nixon administration personnel involved in the Watergate scandal

- Nixon administration personnel

- Pennsylvania Republicans

- People from Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania

- People of the Falklands War

- Politicians from Philadelphia

- Reagan administration cabinet members

- Recipients of the Air Force Distinguished Service Medal

- Recipients of the Air Medal

- Recipients of the Defense Distinguished Service Medal

- Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United States)

- Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United States)

- Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army)

- American recipients of the Gallantry Cross (Vietnam)

- Recipients of the Legion of Merit

- Recipients of the National Order of Vietnam

- Recipients of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal

- Recipients of the Silver Star

- St. Joseph's Preparatory School alumni

- United States Army Vice Chiefs of Staff

- United States Army War College alumni

- United States Army generals

- United States Army personnel of the Korean War

- United States Army personnel of the Vietnam War

- United States Deputy National Security Advisors

- United States Military Academy alumni

- United States secretaries of state

- United States presidential advisors

- University of Notre Dame alumni

- White House chiefs of staff