Albanoid

| Albanoid | |

|---|---|

| Albanic, Adriatic Indo-European, Illyric, Illyrian complex, Western Paleo-Balkan | |

| Geographic distribution | Western Balkans, Southern Italy |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Albanoid |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Linguasphere | 55 (phylozone) |

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

Albanoid or Albanic is a branch or subfamily of the Indo-European (IE) languages, of which Albanian language varieties are the only surviving representatives. In current classifications of the IE language family, Albanian is grouped in the same IE branch with Messapic, an ancient extinct language of Balkan provenance that is preserved in about six hundred inscriptions from Iron Age Apulia.[1] This IE subfamily is alternatively referred to as Illyric, Illyrian complex, Western Paleo-Balkan, or Adriatic Indo-European.[2] Concerning "Illyrian" of classical antiquity, it is not clear whether the scantly documented evidence actually represents one language and not material from several languages, but if "Illyrian" is defined as the ancient precursor of Albanian or the sibling of Proto-Albanian it is automatically included in this IE branch.[3] Albanoid is also used to explain Albanian-like pre-Romance features found in Eastern Romance languages.[4]

Due to the relatively poor knowledge of Messapic, its belonging to the IE branch of Albanian has been described by some as currently speculative,[5] although it is supported by available fragmentary linguistic evidence that shows common characteristic innovations and a number of significant lexical correspondences between the two languages.[6]

Nomenclature

[edit]The IE subfamily that gave rise to Albanian and Messapic is alternatively referred to as 'Albanoid', 'Illyric', 'Illyrian complex', 'Western Palaeo-Balkan', or 'Adriatic Indo-European'.[2] 'Albanoid' is considered more appropriate as it refers to a specific ethnolinguistically pertinent and historically compact language group.[7] Concerning "Illyrian" of classical antiquity, it is not clear whether the scantly documented evidence actually represents one language and not material from several languages.[8] However, if "Illyrian" is defined as the ancient precursor language to Albanian, for which there is some linguistic evidence,[9] and which is often supported for obvious geographic and historical reasons,[10] or the sister language of Proto-Albanian, it is automatically included in this IE branch.[3] 'Albanoid' is also used to explain Albanian-like pre-Romance features found in Eastern Romance languages.[4]

The term 'Albanoid' for the IE subfamily of Albanian was firstly introduced by Indo-European historical linguist Eric Pratt Hamp (1920 – 2019),[11] and thereafter adopted by a series of linguists.[12] A variant term is 'Albanic'.[13] The root ultimately originated from the name of the Illyrian tribe Albanoi,[14] early generalized to all the Illyrian tribes speaking the same idiom.[15] The process was similar to the spread of the name Illyrians from a small group of people on the Adriatic coast, the Illyrioi.[16]

History

[edit]Albanoid and other Paleo-Balkan languages had their formative core in the Balkans after the Indo-European migrations in the region.[17]

Indo-European diversification and dispersal

[edit]

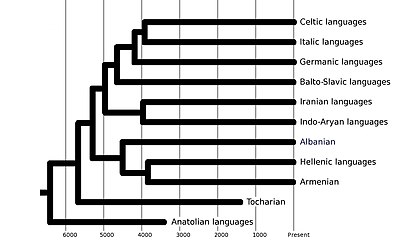

Although research is ongoing, in current phylogenetic tree models of the Indo-European language family, the IE dialect that gave rise to Albanian splits from "Post-Tocharian Indo-European", that is the residual Indo-European unity ("Core Indo-European") which remained after Tocharian's splitting from "Post-Anatolian Indo-European".[20] The transition between the Basal IE and Core IE speech communities appears to have been marked by an economic shift from a mainly non-agricultural economy to a mixed agro-pastoral economy. The lack of evidence for agricultural practices in early, eastern Yamnaya of the Don-Volga steppe does not offer a perfect archaeological proxy for the Core IE language community, rather western Yamnaya groups around or to the west of the Dnieper River better reflect that archaeological proxy.[21] The common stage between the Late Proto-Indo-European dialects of Pre-Albanian, Pre-Armenian, and Pre-Greek, is considered to have occurred in the Late Yamnaya period after the westward migrations of Early Yamnaya across the Pontic–Caspian steppe, also remaining in the western steppe for a prolonged period of time separated from the Proto-Indo-European dialects that later gave rise in Europe to the Corded Ware and Bell Beaker cultures.[22]

Yamnaya steppe pastoralists apparently migrated into the Balkans about 3000 to 2500 BCE, and they soon admixed with the local populations, which resulted in a tapestry of various ancestry from which speakers of the Albanian and other Paleo-Balkan languages emerged.[23] The Albanoid speech was among the Indo-European languages that replaced the pre-Indo-European languages of the Balkans,[24] which left traces of the Mediterranean-Balkan substratum.[25] On the other hand, Baltic and Slavic, together with Germanic, as well as possibly Celtic and Italic, apparently emerged on the territory of the Corded Ware archaeological horizon of the late 4th and the 3rd millennium BCE. The distinction between the southern European languages (in particular Albanian and Greek) and the northern and western European languages (Baltic, Slavic, Germanic, Celtic, and Italic) is further reflected by the frequently shared lexical items of northwest pre-Indo-European substratum among the latter languages.[26]

| The Palaeo-Balkanic Indo-European branch based on the chapters "Albanian" (Hyllested & Joseph 2022) and "Armenian" (Olsen & Thorsø 2022) in Olander (ed.) The Indo-European Language Family |

Classification

[edit]Recent IE phylogenetic studies group the Albanoid subfamily in the same IE branch with Graeco-Phrygian and Armenian, labelled '(Palaeo-)Balkanic Indo-European',[27] based on shared Indo-European morphological, lexical, and phonetic innovations, archaisms, as well as shared lexical proto-forms from a common pre-Indo-European substratum.[28][note 1][note 2] Innovative creations of agricultural terms shared only between Albanian and Greek were formed from non-agricultural PIE roots through semantic changes to adapt them for agriculture. Since they are limited only to Albanian and Greek, they could be traced back with certainty only to their last common IE ancestor, and not projected back into Proto-Indo-European.[32]

Shortly after they had diverged from one another, Pre-Albanian, Pre-Greek, and Pre-Armenian undoubtedly also underwent a longer period of contact, as shown by common correspondences that are irregular for other IE languages. Furthermore, intense Greek–Albanian contacts certainly have occurred thereafter.[33]

Family tree

[edit]

- Albanoid

- Proto-Albanian

- Common Albanian

- Gheg Albanian (Northern Albanian dialect)

- Northern Gheg

- Northwestern Gheg

- Malsia e Madhe (in the region of Malësia)

- Shkodra and Lezha (in the regions of Shkodër and Lezhë)

- Arbanasi (in Zadar, Croatia)

- Istrian Albanian (extinct)

- Northeastern Gheg (in northeast Albania and most of Kosovo)

- Northwestern Gheg

- Central-Southern Gheg

- Central Gheg

- Southern Gheg (includes the capital Tirana)

- Transitional Gheg

- Southern Elbasan

- Southern Peqin

- Northwestern Gramsh

- Transitional Gheg

- Northern Gheg

- Tosk Albanian (Southern Albanian dialect)

- Northern Tosk (basis of Standard Modern Albanian but not identical)

- Northeastern Tosk

- Mandritsa Tosk (in far southeast Bulgaria)

- Ukrainian Tosk (in Ukraine)

- Western Thracian Tosk (in Western Thrace)

- Northeastern Tosk

- Southern Tosk

- Lab

- Cham

- Suliot (extinct)

- Arbëresh (in Southern Italy)

- Puglia Arbëresh / Apulo-Arbëresh

- Molise Arbëresh / Molisan-Arbëresh

- Campania Arbëresh / Campano-Arbëresh

- Basilicata Arbëresh / Basilicatan-Arbëresh

- Calabria Arbëresh / Calabro-Arbëresh

- Sicilia Arbëresh / Siculo-Arbëresh

- Arvanitika (in Greece)

- Northwestern Arvanitika

- Southcentral Arvanitika

- Southern Arvanitika

- Northern Tosk (basis of Standard Modern Albanian but not identical)

- Gheg Albanian (Northern Albanian dialect)

- Common Albanian

- Messapic (extinct)

- Illyrian (extinct) (?) (if sibling and not precursor of Albanian)

- Pre-Eastern Romance (extinct) (?) (the non-Albanian, but Albanian-like features in Eastern Romance)

- Proto-Albanian

Notes

[edit]- ^ A remarkable PIE root that underwent in Albanian, Armenian, and Greek a common evolution and semantic shift in the post PIE period is PIE *mel-i(t)- 'honey', from which Albanian bletë, Armenian mełu, and Greek μέλισσα, 'bee' derived.[29] However, the Armenian term features -u- through the influence of the PIE *médʰu 'mead', which constitutes an Armenian innovation that isolates it from the Graeco-Albanian word.[30]

- ^ A remarkable common proto-form for "goat" of non-Indo-European origin is exclusively shared between Albanian, Armenian, and Greek. It could have been borrowed at a pre-stage that was common to these languages from a pre-Indo-European substrate language that in turn had loaned the word from a third source, from which the pre-IE substrate of the proto-form that is shared between Balto-Slavic and Indo-Iranian could also have borrowed it. Hence it can be viewed as an old cultural word, which was slowly transmitted to two different pre-Indo-European substrate languages, and then independently adopted by two groups of Indo-European speakers, reflecting a post-Proto-Indo-European linguistic and geographic separation between a Balkan group consisting of Albanian, Greek, and Armenian, and a group to the North of the Black Sea consisting of Balto-Slavic and Indo-Iranian.[31]

- ^ The map does not imply that the Albanian language is the majority or the only spoken language in these areas.

References

[edit]- ^ Hyllested & Joseph 2022, p. 235; Friedman 2020, p. 388; Majer 2019, p. 258; Trumper 2018, p. 385; Yntema 2017, p. 337; Mërkuri 2015, pp. 65–67; Ismajli 2015, pp. 36–38, 44–45; Ismajli 2013, p. 24; Hamp & Adams 2013, p. 8; Demiraj 2004, pp. 58–59; Hamp 1996, pp. 89–90.

- ^ a b Crăciun 2023, pp. 77–81; Friedman 2023, p. 345; Hyllested & Joseph 2022, p. 235; Friedman 2022, pp. 189–231; Trumper 2020, p. 101; Trumper 2018, p. 385; Baldi & Savoia 2017, p. 46; Yntema 2017, p. 337; Ismajli 2015, pp. 36–38, 44–45; Ismajli 2013, p. 24; Hamp & Adams 2013, p. 8; Schaller 2008, p. 27; Demiraj 2004, pp. 58–59; Hamp 2002, p. 249; Ködderitzsch 1998, p. 88; Ledesma 1996, p. 38.

- ^ a b Friedman 2022, pp. 189–231; Friedman 2020, p. 388; Baldi & Savoia 2017, p. 46; Hamp & Adams 2013, p. 8; Holst 2009, pp. 65–66

- ^ a b Hamp 1981, p. 130; Joseph 1999, p. 222; Hamp 2002, p. 249; Joseph 2011, p. 128; Ismajli 2015, pp. 36–38, 44–45; Trumper 2018, pp. 383–386; Friedman 2019, p. 19.

- ^ Hyllested & Joseph 2022, p. 240: "Technically speaking, from a genealogical standpoint, Messapic likely is the closest IE language to Albanian (Matzinger 2005). However, in the absence of sufficient evidence, that connection must remain speculative.

- ^ Trumper 2018, pp. 383–386; Friedman 2020, p. 388; Friedman 2011, pp. 275–291.

- ^ Trumper 2018, p. 385; Manzini 2018, p. 15.

- ^ Holst 2009, p. 65–66.

- ^ Friedman 2022, pp. 189–231; Holst 2009, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Friedman 2022, pp. 189–231; Coretta et al. 2022, p. 1122; Matasović 2019, p. 5; Parpola 2012, p. 131; Beekes 2011, p. 25; Fortson 2010, p. 446; Holst 2009, pp. 65–66; Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 11.

- ^ Joseph 2011, p. 128.

- ^ Huld 1984, p. 158; Ledesma 1996, p. 38; Joseph 1999, p. 222; Trumper 2018, p. 385; Friedman 2023, p. 345; Crăciun 2023, pp. 77–81.

- ^ Friedman 2022, pp. 189–231; Friedman & Joseph 2017, pp. 55–87; Friedman 2000, p. 1; "Albanic" in Linguasphere Observatory.

- ^ Demiraj 2020, p. 33; Campbell 2009, p. 120.

- ^ Demiraj 2020, p. 33.

- ^ Campbell 2009, p. 120.

- ^ Friedman 2022, pp. 189–231; Lazaridis & Alpaslan-Roodenberg 2022, pp. 1, 10.

- ^ Chang, Chundra & Hall 2015, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Hyllested & Joseph 2022, p. 241.

- ^ Hyllested & Joseph 2022, p. 241; Koch 2020, pp. 24, 50, 54; Chang, Chundra & Hall 2015, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Kroonen et al. 2022, pp. 1, 11, 26, 28.

- ^ Nielsen 2023, pp. 225, 231–235.

- ^ Lazaridis & Alpaslan-Roodenberg 2022, pp. 1, 10.

- ^ Friedman 2023, p. 345.

- ^ Demiraj 2013, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Matasović 2013, p. 97.

- ^ Hyllested & Joseph 2022, p. 241; Olsen & Thorsø 2022, p. 209; Thorsø 2019, p. 258; Chang, Chundra & Hall 2015, pp. 199–200; Holst 2009, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Hyllested & Joseph 2022, p. 241; Olsen & Thorsø 2022, p. 209; Thorsø 2019, p. 258; Kroonen 2012, p. 246; Holst 2009, pp. 65–66.

- ^ van Sluis 2022, p. 16; Hyllested & Joseph 2022, p. 238.

- ^ Hyllested & Joseph 2022, p. 238.

- ^ Thorsø 2019, p. 255; Kroonen 2012, p. 246.

- ^ Kroonen et al. 2022, pp. 11, 26, 28

- ^ Thorsø 2019, p. 258.

Sources

[edit]- Baldi, Benedetta; Savoia, Leonardo M. (2017). "Cultura e identità nella lingua albanese" [Culture and Identity in the Albanian Language]. LEA - Lingue e Letterature d'Oriente e d'Occidente. 6 (6): 45–77. doi:10.13128/LEA-1824-484x-22325. ISSN 1824-484X.

- Beekes, Robert S. P. (2011). Comparative Indo-European Linguistics: An Introduction. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-1185-9.

- Campbell, Duncan R. J. (2009). The so-called Galatae, Celts, and Gauls in the Early Hellenistic Balkans and the Attack on Delphi in 280–279 BC (Thesis). University of Leicester.

- Chang, Will; Chundra, Cathcart; Hall, David (2015). "Ancestry-constrained phylogenetic analysis supports the Indo-European steppe hypothesis" (PDF). Language. 91 (1): 194–244. doi:10.1353/lan.2015.0005. S2CID 143978664.

- Coretta, Stefano; Riverin-Coutlée, Josiane; Kapia, Enkeleida; Nichols, Stephen (16 August 2022). "Northern Tosk Albanian". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 53 (3): 1122–1144. doi:10.1017/S0025100322000044. hdl:20.500.11820/ebce2ea3-f955-4fa5-9178-e1626fbae15f.

- Crăciun, Radu (2023). "Diellina, një bimë trako-dake me emër proto-albanoid" [Diellina, a Thracian-Dacian plant with a Proto-Albanoid name]. Studime Filologjike (1–2). Centre of Albanological Studies: 77–83. doi:10.62006/sf.v1i1-2.3089. ISSN 0563-5780.

- Demiraj, Shaban (2004). "Gjendja gjuhësore e Gadishullit Ballkanik në lashtësi" [The linguistic situation of the Balkan Peninsula in antiquity]. Gjuhësi Ballkanike [Balkan Linguistics] (in Albanian). Academy of Sciences of Albania. ISBN 9789994363001.

- Demiraj, Bardhyl (2013). Spiro, Aristotel (ed.). "Gjurmë të substratit mesdhetar-ballkanik në shqipe dhe greqishte: shq. rrush dhe gr. ῥώξ si rast studimi" [Traces of the Mediterranean-Balkan substratum in Albanian and Greek: Alb. rrush and Gr. ῥώξ as case study]. Albanohellenica (5). Albanian-Greek Philological Association: 23–40.

- Demiraj, Bardhyl (2020). "The Evolution of Albanian". Studia Albanica (2). Academy of Sciences of Albania: 33–40. ISSN 0585-5047.

- Friedman, Victor A. (2000). "After 170 years of Balkan Linguistics: Whither the Millennium?". Mediterranean Language Review. 12. O. Harrassowitz: 1–15. ISSN 0724-7567.

- Friedman, Victor A. (2011). "The Balkan Languages and Balkan Linguistics". Annual Review of Anthropology. 40: 275–291. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-081309-145932.

- Friedman, Victor A.; Joseph, Brian D. (2017). "Reassessing Sprachbunds: A View from the Balkans". The Cambridge Handbook of Areal Linguistics. Cambridge Handbooks in Language and Linguistics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 55–87. ISBN 9781316839454.

- Friedman, Victor A. (2019). "In Memoriam: Eric Pratt Hamp (1920–2019)" (PDF). Rocznik Slawistyczny. LXVIII: 13–24. doi:10.24425/rslaw.2019.130009. ISSN 0080-3588.

- Friedman, Victor A. (2020). "The Balkans". In Evangelia Adamou, Yaron Matras (ed.). The Routledge Handbook of Language Contact. Routledge Handbooks in Linguistics. Routledge. pp. 385–403. ISBN 9781351109147.

- Friedman, Victor A. (2022). "The Balkans". In Salikoko Mufwene, Anna Maria Escobar (ed.). The Cambridge Handbook of Language Contact: Volume 1: Population Movement and Language Change. Cambridge Handbooks in Language and Linguistics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 189–231. ISBN 9781009115773.

- Friedman, Victor A. (2023). "The importance of Aromanian for the study of Balkan language contact in the context of Balkan-Caucasian parallels". In Aminian Jazi, Ioana; Kahl, Thede (eds.). Ethno-Cultural Diversity in the Balkans and the Caucasus. Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. pp. 345–360. doi:10.2307/jj.3508401.16. JSTOR jj.3508401.16.

- Fortson, Benjamin Wynn IV (2010). Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4443-5968-8.

- Hamp, Eric P. (1981). "Albanian edhe "and"". In Yoël L. Arbeitman, Allan R. Bomhard (ed.). Bono Homini Donum: Essays in Historical Linguistics, in Memory of J. Alexander Kerns. (2 volumes). Current Issues in Linguistic Theory. Vol. 16. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 127–132. ISBN 9789027280954.

- Hamp, Eric P. (1996). "Varia". Études Celtiques. 32: 87–90. doi:10.3406/ecelt.1996.2087. ISSN 0373-1928.

- Hamp, Eric P. (2002). "On Serbo-Croatian's Historic Laterals". In Friedman, Victor A.; Dyer, Donald L. (eds.). Of all the Slavs my favorites. Indiana Slavic studies. Vol. 12. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University. pp. 243–250. OCLC 186020548.

- Hamp, Eric; Adams, Douglas (August 2013). "The Expansion of the Indo-European Languages: An Indo-Europeanist's Evolving View" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. 239.

- Holst, Jan Henrik (2009). Armenische Studien (in German). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447061179.

- Huld, Martin E. (1984). Basic Albanian Etymologies. Columbus, OH: Slavica Publishers. ISBN 9780893571351.

- Hyllested, Adam; Joseph, Brian D. (2022). "Albanian". The Indo-European Language Family. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108499798.

- Ismajli, Rexhep (2013). "Diskutime për prejardhjen e gjuhës shqipe" [Discussions About the Origin of the Albanian Language]. In Bardh Rugova (ed.). Seminari XXXII Ndërkombëtar për Gjuhën, Letërsinë dhe Kulturën Shqiptare [The XXXII International Seminar on Albanian Language, Literature and Culture] (in Albanian). Prishtinë: University of Prishtina.

- Ismajli, Rexhep (2015). Eqrem Basha (ed.). Studime për historinë e shqipes në kontekst ballkanik [Studies on the History of Albanian in the Balkan context] (in Albanian). Prishtinë: Kosova Academy of Sciences and Arts, special editions CLII, Section of Linguistics and Literature.

- Joseph, Brian D. (1999). "Romanian and the Balkans: Some comparative perspectives". In E. F. K. Koerner; Sheila M. Embleton; John Earl Joseph; Hans-Josef Niederehe (eds.). The Emergence of the Modern Language Sciences: Methodological perspectives and applications. The Emergence of the Modern Language Sciences: Studies on the Transition from Historical-comparative to Structural Linguistics in Honour of E.F.K. Koerner. Vol. 2. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 217–238. ISBN 9781556197604.

- Joseph, Brian D. (2011). "Featured Review". Acta Slavica Iaponica (pdf). 29: 123–131. hdl:2115/47633.

- Ködderitzsch, Rolf (1998). Uniwersytet Łódzki (ed.). "Albanisch und Slawisch – zwei indogermanische Sprachen im Vergleich". Studia Indogermanica Lodziensia (in German). Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: 79–88. ISBN 9788371711343.

- Koch, John T. (2020). Celto-Germanic, Later Prehistory and Post-Proto-Indo-European vocabulary in the North and West. University of Wales Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies. ISBN 9781907029325.

- Kroonen, Guus (2012). "Non-Indo-European root nouns in Germanic: evidence in support of the Agricultural Substrate Hypothesis". In Riho Grünthal, Petri Kallio (ed.). A Linguistic Map of Prehistoric Northern Europe. Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Toimituksia = Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne. Vol. 266. Société Finno-Ougrienne. pp. 239–260. ISBN 9789525667424. ISSN 0355-0230.

- Kroonen, Guus; Jakob, Anthony; Palmér, Axel I.; van Sluis, Paulus; Wigman, Andrew (12 October 2022). "Indo-European cereal terminology suggests a Northwest Pontic homeland for the core Indo-European languages". PLOS ONE. 17 (10): e0275744. Bibcode:2022PLoSO..1775744K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275744. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 9555676. PMID 36223379.

- Lazaridis, Iosif; Alpaslan-Roodenberg, Songül; et al. (26 August 2022). "The genetic history of the Southern Arc: A bridge between West Asia and Europe". Science. 377 (6609): eabm4247. doi:10.1126/science.abm4247. PMC 10064553. PMID 36007055. S2CID 251843620.

- Ledesma, Manuel Sanz (1996). Ediciones Clásicas (ed.). El Albanés: gramática, historia, textos. Instrumenta studiorum: Lenguas indoeuropeas (in Spanish). ISBN 9788478822089.

- Majer, Marek (2019). "Parahistoria indoevropiane e fjalës shqipe për 'motrën'" [Indo-European Prehistory of the Albanian Word for 'Sister']. Seminari Ndërkombëtar për Gjuhën, Letërsinë dhe Kulturën Shqiptare [International Seminar for Albanian Language, Literature and Culture] (in Albanian). 1 (38). University of Prishtina: 252–266. ISSN 2521-3687.

- Mallory, J. P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- Manzini, M. Rita (2018). "Introduction: Structuring thought, externalizing structure: Variation and universals". In Grimaldi, Mirko; Lai, Rosangela; Franco, Ludovico; Baldi, Benedetta (eds.). Structuring Variation in Romance Linguistics and Beyond: In Honour of Leonardo M. Savoia. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 9789027263179.

- Matasović, Ranko (2013). "Substratum words in Balto-Slavic". Filologija. 60: 75–102. eISSN 1848-8919. ISSN 0449-363X.

- Matasović, Ranko (2019). A Grammatical Sketch of Albanian for Students of Indo European (PDF). Zagreb. p. 39.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mërkuri, Nexhip (2015). "Gjuhësia e përgjithshme dhe këndvështrimet bashkëkohore për Epirin dhe mesapët" [General Linguistics and Contemporary Perspectives on Epirus and the Messapians]. In Ibrahimi, Zeqirija (ed.). Shaban Demiraj – figurë e shquar e albanologjisë dhe ballkanologjisë [Shaban Demiraj – prominent figure of Albanianology and Balkanology] (in Albanian). Instituti i Trashëgimisë Shpirtërore e Kulturore të Shqiptarëve – Shkup. p. 57. ISBN 9786084653240.

- Nielsen, R. T. (2023). Prehistoric loanwords in Armenian: Hurro-Urartian, Kartvelian, and the unclassified substrate (PhD). Leiden University. hdl:1887/3656151.

- Olsen, Birgit Anette; Thorsø, Rasmus (2022). "Armenian". In Olander, Thomas (ed.). The Indo-European Language Family: A Phylogenetic Perspective. Cambridge University Press. pp. 202–222. doi:10.1017/9781108758666.012. ISBN 9781108758666.

- Parpola, Asko (2012). "Formation of the Indo-European and Uralic (Finno-Ugric) language families in the light of archaeology: Revised and integrated 'total' correlations". In Riho Grünthal, Petri Kallio (ed.). A Linguistic Map of Prehistoric Northern Europe. Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Toimituksia / Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne. Vol. 266. Helsinki: Société Finno-Ougrienne. pp. 119–184. ISBN 9789525667424. ISSN 0355-0230.

- Schaller, Helmut W. (2008). "Balkanromanischer Einfluss auf das Bulgarische". In Biljana Sikimić, Tijana Ašić (ed.). The Romance Balkans (in English and German). Balkanološki institut SANU. pp. 27–36. ISBN 9788671790604.

- van Sluis, P. S. (2022). "Beekeeping in Celtic and Indo-European". Studia Celtica. 56 (1): 1–28. doi:10.16922/SC.56.1. hdl:1887/3655383.

- Thorsø, Rasmus (2019). "Two Balkan Indo-European Loanwords". In Matilde Serangeli; Thomas Olander (eds.). Dispersals and Diversification: Linguistic and Archaeological Perspectives on the Early Stages of Indo-European. Brill's Studies in Indo-European Languages & Linguistics. Vol. 19. Brill. pp. 251–262. ISBN 9789004416192.

- Trumper, John (2018). "Some Celto-Albanian isoglosses and their implications". In Grimaldi, Mirko; Lai, Rosangela; Franco, Ludovico; Baldi, Benedetta (eds.). Structuring Variation in Romance Linguistics and Beyond: In Honour of Leonardo M. Savoia. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 9789027263179.

- Trumper, John (2020). "The role of Albanoid groups (Albanian and Italoalbanian) in language transmission (Italy and Calabria as exemplum". In Iamajli, Rexhep (ed.). Studimet albanistike në Itali [Albanistic studies in Italy]. ASHAK. pp. 101–108.

- Yntema, Douwe (2017). "The Pre-Roman Peoples of Apulia (1000-100 BC)". In Gary D. Farney, Guy Bradley (ed.). The Peoples of Ancient Italy. De Gruyter Reference. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. pp. 337–. ISBN 9781614513001.