Afghan Civil War (1992–1996)

| Second Afghan Civil War | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Afghan conflict and the Iran–Saudi Arabia proxy conflict (after Dec. 1992) | ||||||||

A picture of Kabul's city center, Jada-e Maiwand, depicting the widespread destruction of city's infrastructure caused by the war, c.1993. | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

Regional Kandahar Militia Leaders

|

Supported by: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

| 26,759 killed (per UCDP ) | ||||||||

The 1992–1996 Afghan Civil War, also known as the Second Afghan Civil War, took place between 28 April 1992—the date a new interim Afghan government was supposed to replace the Republic of Afghanistan of President Mohammad Najibullah—and the Taliban's occupation of Kabul establishing the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan on 27 September 1996.[6]

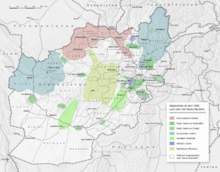

The war immediately followed the 1989–1992 civil war with the mujahideen victory and dissolution of the Republic of Afghanistan in April 1992. The Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin, led by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and supported by Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), refused to form a coalition government and tried to seize Kabul with the help of Khalqists. On 25 April 1992 fighting broke out between three, and later five or six, mujahideen armies. Alliances between the combatants were transitory throughout the war.

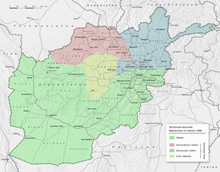

The Taliban, a new militia formed with support from Pakistan and ISI, became dominant in 1995–96. It captured Kandahar in late-1994, Herat in 1995, Jalalabad in early-September 1996, and Kabul by late-September 1996. The Taliban fought the newly-formed Northern Alliance in the subsequent 1996-2001 civil war.

Kabul's population fell from two million to 500,000 during the 1992–1996 war; 500,000 fled during the first four months.

Overall, the Afghan Civil War of 1992–1996 was a period of intense conflict and suffering for the people of Afghanistan. The collapse of the Soviet-backed government, ethnic and religious divisions, and external involvement all contributed to the conflict. The legacy of this period of Afghan history continues to shape the country's politics and society today.

Background

[edit]The Republic of Afghanistan quickly collapsed in 1992 after the Russian Federation halted its support to it. On 16 April 1992 Afghan President Mohammad Najibullah stepped down and the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan was dissolved.

Several mujahideen parties started negotiations to form a national coalition government. But one group, the Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin led by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, presumably supported and directed by Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), did not join the negotiations and announced to conquer Kabul alone. Hekmatyar moved his troops to Kabul, and was allowed into the town soon after 17 April. The other mujahideen groups also entered Kabul, on 24 April, to prevent Hekmatyar from taking over the city and the country.[7][8] This ignited a civil war between five or six rival armies, most of them backed by foreign states. Several Mujahideen groups proclaimed the establishment of the Islamic State of Afghanistan on 28 April 1992 with Sibghatullah Mojaddedi as acting president, but this never attained real authority over Afghanistan.

Outline of civil war (1992–96)

[edit]War over Kabul (28 April 1992–93)

[edit]Fighting and rivalry over Kabul had started on 25 April 1992, involving six armies: Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin, Jamiat-e Islami, Harakat-i-Inqilab-i-Islami, Ittehad-e Islami, Hezb-i Wahdat and Junbish-i Milli. Mujahideen warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar (Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin), after talks with mujahideen leader Ahmad Shah Massoud (Jamiat-e Islami) on 25 May 1992, was offered the position of prime minister in President Mujaddidi's – paralyzed – 'interim government'. But this agreement shattered already on 29 May when Mujaddidi accused Hekmatyar of having rockets fired at his plane returning from Islamabad.[9]

By 30 May 1992, Jamiat-e Islami and Junbish-i Milli mujahideen forces were fighting against Hekmatyar's Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin again in southern Kabul. In May[10] or early June, Hekmatyar started shelling all around Kabul,[9][11] presumably with substantial support from the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI).[10] Junbish-i Milli and Jamiat-e Islami in June shelled areas south of Kabul, Ittehad-e Islami and Hezb-i Wahdat were fighting each other in west Kabul. At the end of June 1992, Burhanuddin Rabbani took over the interim Presidency from Mujaddidi, as provided in the Peshawar Accords[9] – a paralyzed 'interim government' though, right from its proclamation in April 1992.[12]

In the rest of 1992, hundreds of rockets hit Kabul, thousands, mostly civilians, were killed, half a million people fled the city. In 1993, the rivalling militia factions continued their fights over Kabul, several cease-fires and peace accords failed.[13] According to Human Rights Watch, in the period 1992–95, five different mujahideen armies contributed to heavily damaging Kabul,[14][15] though other analysts blame especially the Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin group.[10][16]

War expanding (1994)

[edit]In January 1994, Dostum's Junbish-i Milli forces and Mazari's Hezb-i Wahdat joined sides with Hekmatyar's Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin.[13] Fighting this year also broke out in the northern town of Mazar-i-Sharif. In November 1994, the new Deobandi jihadist militia known as Taliban conquered Kandahar city and by January 1995 they controlled 12 Afghan provinces.[17]

War spreads throughout Afghanistan and the rise of the Taliban (1995–96)

[edit]In 1995, the civil war in Afghanistan raged between at least four parties: the Burhanuddin Rabbani 'interim government' with Ahmad Shah Massoud and his Jamiat-e Islami forces; the Taliban; Abdul Rashid Dostum with his Junbish-e Melli-ye Islami forces; and the Hezb-i Wahdat.[13] The Taliban captured Ghazni (south of Kabul) and Maidan Wardak Province (west of Kabul) and in February approached Kabul. The Taliban then continued shelling Kabul and attacking Massoud's forces in Kabul.

In 1996, the Taliban grew stronger, as analysts say with decisive support from Pakistan.[18] This induced some other warring factions to form new alliances, starting with the Burhanuddin Rabbani 'interim government' and Hekmatyar with his Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin in early March. In July, a new government was formed by five factions: Rabbani's Jamiat-e Islami, the Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin, Abdul Rasul Sayyaf's Ittehad-e Islami, the Harakat-i-Islami, and Hezb-i Wahdat's Akbari faction. Such alliances did not stop the advance and victories of the Taliban. On 27 September 1996, the Taliban, took control of Kabul and established the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.[6]

Main participants

[edit]Islamic State of Afghanistan

[edit]Jamiat-e Islami

[edit]Jamiat-e Islami (‘Islamic Society’) was a political party of ethnic Tajiks, and included one of the strongest mujahideen militias in Afghanistan since 1979. Its military wing was commanded by Ahmad Shah Massoud. During the Soviet–Afghan War, his role as a powerful mujahideen insurgent leader earned him the nickname of "Lion of Panjshir" (شیر پنجشیر) among his followers as he successfully resisted the Soviets from taking Panjshir Valley. In 1992 he signed the Peshawar Accord, a peace and power-sharing agreement, in the post-communist Islamic State of Afghanistan,[19] and was so appointed as the Minister of Defense as well as the government's main military commander. His militia fought to defend the capital Kabul against militias led by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and other warlords who were bombing the city[20]—and eventually the Taliban, who started to lay siege to the capital in January 1995 after the city had seen fierce fighting with at least 60,000 civilians killed.[21][22]

Hezb-e Islami Khalis

[edit]Hezb-e Islami Khalis was an Afghan political movement under Mohammad Yunus Khalis, who separated from Gulbuddin Hekmatyar's Hezb-e Islami and formed his own resistance group in 1979. After the fall of the Communist regime in 1992, Khalis participated in the Islamic Interim Government. He was a member of the Leadership Council (Shura-ye Qiyaadi), but held no other official post. Instead of moving to Kabul, he chose to remain in Nangarhar. His party controlled major parts of this politically and strategically important province. The Taliban brought Nangarhar under their control in September 1996 and Khalis was supportive of the Taliban movement and had a close relationship with its commanders.

Ittehad-e Islami / Saudi Arabia

[edit]The Sunni Pashtun Ittehad-e Islami bara-ye Azadi-ye Afghanistan ('Islamic Union for the Liberation of Afghanistan') of Abdul Rasul Sayyaf was supported by Sunni Wahabbi Saudi Arabia, to maximize Wahhabi influence.[23] After the forced withdrawal of the demoralised Soviet forces in 1989, and the overthrow of the Mohammad Najibullah regime in 1992, Sayyaf's organization's human rights record became noticeably worse, underlined by their involvement in the infamous massacres and rampages in the Hazara Kabul neighbourhood of Afshar in 1992–1993 during the Battle of Kabul.[24] Sayyaf's faction was responsible for, "repeated human butchery", when his faction of Mujahideen turned on civilians and the Shia Hezb-i Wahdat group in west Kabul[25] starting May 1992.[24] Amnesty International reported that Sayyaf's forces rampaged through the mainly Shi'ite Tajik (Qizilbash) Afshar neighborhood of Kabul, slaughtering and raping inhabitants and burning homes.[26] Sayyaf, who was allied with the de jure Kabul government of Burhanuddin Rabbani, did not deny the abductions of Hazara civilians, but merely accused the Hezb-i Wahdat militia of being an agent of the theocratic Iranian government.[24]

Harakat-i-Inqilab-i-Islami

[edit]Mohammad Nabi Mohammadi, leader of the Harakat-i-Inqilab-i-Islami ('Islamic Revolution Movement'), became the Vice President of Afghanistan in the Mujahideen government. However, when the Mujahideen leaders opened their weapons at each other and the civil war in Afghanistan started, he resigned from his post and forbade the troops loyal to him from taking part in the war. He remained in Pakistan and tried his best to stop the war between Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, Burhanuddin Rabbani and Abdul Rasul Sayyaf.[27][28] In 1996, the Taliban took control of Afghanistan. Most of the Taliban leaders were the students of Molvi Mohammad Nabi Mohammadi.[29] Mohammadi, however, maintained a good relationship with the Taliban.

Hezb-i Wahdat / Iran

[edit]The Shia Hazara Hizb-e Wahdat-e Islami Afghanistan ('Islamic Unity Party of Afghanistan') of Abdul Ali Mazari was strongly supported by Shia Iran, according to Human Rights Watch, with Iran's Ministry of Intelligence and National Security officials providing direct orders.[23] After the fall of Kabul, the Afghan political parties agreed on a peace and power-sharing agreement, the Peshawar Accords. The Peshawar Accords created the Islamic State of Afghanistan and appointed an interim government for a transitional period to be followed by general elections. According to Human Rights Watch:

The sovereignty of Afghanistan was vested formally in the Islamic State of Afghanistan, an entity created in April 1992, after the fall of the Soviet-backed Najibullah government. ... With the exception of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar's Hezb-e Islami, all of the parties... were ostensibly unified under this government in April 1992. ... Hekmatyar's Hezbe Islami, for its part, refused to recognize the government for most of the period discussed in this report and launched attacks against government forces but the shells and rockets fell everywhere in Kabul resulting in many civilian casualties.[30]

The Hezb-i Wahdat initially took part in the Islamic State of Afghanistan and held some posts in the government. Soon, however, conflict broke out between the Hazara Hezb-i Wahdat of Mazari, the Wahabbi Pashtun Ittehad-e Islami of warlord Abdul Rasul Sayyaf supported by Saudi Arabia.[30][31][32] The Islamic State's defense minister Ahmad Shah Massoud tried to mediate between the factions with some success, but the ceasefire remained only temporary. As of June 1992, the Hezb-i Wahdat and the Ittehad-e Islami engaged in violent street battles against each other. With the support of Saudi Arabia,[31] Sayyaf's forces repeatedly attacked western suburbs of Kabul resulting in heavy civilian casualties. Likewise, Mazari's forces were also accused of attacking civilian targets in the west.[33] Mazari acknowledged taking Pashtun civilians as prisoners, but defended the action by saying that Sayyaf's forces took Hazaras first.[34] Mazari's group started cooperating with Hekmatyar's group from January 1993.[35]

Junbish-i Milli / Uzbekistan

[edit]The Junbish-i-Milli Islami Afghanistan ('National Islamic Movement of Afghanistan') militia of former communist and ethnic Uzbek general Abdul Rashid Dostum was backed by Uzbekistan.[10] Uzbek President Islam Karimov was keen to see Dostum controlling as much of Afghanistan as possible, especially in the north along the Uzbek border.[10] Dostum's men would become an important force in the fall of Kabul in 1992. In April 1992, the opposition forces began their march to Kabul against the government of Najibullah. Dostum had allied himself with the opposition commanders Ahmad Shah Massoud and Sayed Jafar Naderi,[36] the head of the Isma'ili community, and together they captured the capital city. He and Massoud fought in a coalition against Gulbuddin Hekmatyar.[37] Massoud and Dostum's forces joined to defend Kabul against Hekmatyar. Some 4000-5000 of his troops, units of his Sheberghan-based 53rd Division and Balkh-based Guards Division, garrisoning Bala Hissar fort, Maranjan Hill, and Khwaja Rawash Airport, where they stopped Najibullah from entering to flee.[38]

Dostum then left Kabul for his northern stronghold Mazar-i-Sharif, where he ruled, in effect, an independent region (or 'proto-state'), often referred as the Northern Autonomous Zone. He printed his own Afghan currency, ran a small airline named Balkh Air,[39] and formed relations with countries including Uzbekistan. While the rest of the country was in chaos, his region remained prosperous and functional, and it won him the support from people of all ethnic groups. Many people fled to his territory to escape the violence and fundamentalism imposed by the Taliban later on.[40] In 1994, Dostum allied himself with Gulbuddin Hekmatyar against the government of Burhanuddin Rabbani and Ahmad Shah Massoud, but in 1995 sided with the government again.[37]

Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin / Pakistan's ISI

[edit]According to the U.S. Special Envoy to Afghanistan in 1989–1992, Peter Tomsen, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar was hired in 1990 by the Pakistani intelligence agency Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) planned to conquer and rule Afghanistan which was delayed until 1992 as a result of US pressure to cancel it.[41] In April 1992, according to self-made Afghan historian Nojumi,[42] the Inter-Services Intelligence helped Hekmatyar by sending hundreds of trucks loaded with weapons and fighters to the southern part of Kabul.[43] In June 1992, Hekmatyar with his Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin ('Islamic party') troops started shelling Kabul.[23] The Director of the Centre for Arab and Islamic Studies at the Australian National University, Amin Saikal, confirmed the Pakistani support in 1992 for Hekmatyar: "Pakistan was keen to gear up for a breakthrough in Central Asia...Islamabad could not possibly expect the new Islamic government leaders ... to subordinate their own nationalist objectives in order to help Pakistan realize its regional ambitions. ... Had it not been for the ISI's logistic support and supply of a large number of rockets, Hekmatyar's forces would not have been able to target and destroy half of Kabul."[10]

Taliban / Pakistan

[edit]The Taliban ('the students') have been described as a movement of religious students (talib) from the Pashtun areas of eastern and southern Afghanistan who had been educated in traditional Islamic schools in Pakistan.[14] The movement was founded in September 1994, promising to "rid Afghanistan of warlords and criminals".[17] Several analysts state that at least since October 1994, Pakistan and especially the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence were heavily supporting the Taliban.[17][44] Amin Saikal stated: "Hekmatyar's failure to achieve what was expected of him [later] prompted the ISI leaders to come up with a new surrogate force [the Taliban]."[10] Also a publication of the George Washington University stated: when Hekmatyar in 1994 had failed to "deliver for Pakistan", Pakistan turned towards a new force: the Taliban.[45]

Ahmad Shah Massoud, involved in the political and military turmoil of Afghanistan since 1973 and therefore not an impartial observer, in early September 1996 described the Taliban as the centre of a wider movement in Afghanistan of armed Islamic radicalism: a coalition of wealthy sheikhs (like Osama bin Laden) and preachers from the Persian Gulf advocating the Saudi's puritanical outlook on Islam which Massoud considered abhorrent to Afghans but also bringing and distributing money and supplies; Pakistani and Arab intelligence agencies; impoverished young students from Pakistani religious schools chartered as volunteer fighters notably for this group called Taliban; and exiled Central Asian Islamic radicals trying to establish bases in Afghanistan for their revolutionary movements.[46]

Although Pakistan initially denied supporting the Taliban,[47] Pakistan's Interior Minister Naseerullah Babar (1993–96) would state in 1999,[48] "we created the Taliban",[49] and Pervez Musharraf, Pakistani President in 2001-2008 and Chief of Army Staff since 1998, wrote in 2006: "we sided" with the Taliban to "spell the defeat" of anti-Taliban forces.[50] According to journalist and author Ahmed Rashid, between 1994 and 1999, an estimated 80,000 to 100,000 Pakistanis trained and fought in Afghanistan on the side of the Taliban.[51]

Atrocities

[edit]In 1992–93, Kabul, the factions of Hezb-i Wahdat, Ittehad-e Islami, Jamiat-e Islami and Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin, would regularly target civilians with attacks, intentionally fire rockets into occupied civilian homes, or random civilian areas.[15] In January–June 1994, 25,000 people died in Kabul due to fighting, with targeted attacks on civilian areas, between an alliance of Dostum's (Junbish-i Milli) with Hekmatyar's (Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin) against Massoud's (Jamiat-e Islami) forces.[52]

In 1993–95, leaders of Jamiat-e Islami, Junbish-i Milli, Hezb-i Wahdat and Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin, could not stop their commanders from committing murder, rape and extortion. Even the various warlords in north Afghanistan descended to such horridness.[14]

Fighting in Kabul

[edit]In 1992–95, Kabul was heavily bombarded and damaged. Some analysts emphasize the role of Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin in "targeting and destroying half of Kabul"[10] or in heavy bombardments especially in 1992.[16] But Human Rights Watch in two reports stated that nearly all armies participating in the 1992–95 period of war contributed to "destroying at least one-third of Kabul, killing thousands of civilians, driving a half million refugees to Pakistan": Jamiat-e Islami, Junbish-i Milli, Hezb-i Wahdat, Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin[14] and Ittehad-e Islami.[15]

As of November 1995, the Taliban also engaged in bombing and shelling Kabul, causing many civilians to be killed or injured.[53][54]

Timeline

[edit]1992

[edit]April–May

[edit]

As of 28 April, an interim government under interim President Sibghatullah Mojaddedi, with interim minister of defense Ahmad Shah Massoud, claimed to be governing Afghanistan, as agreed in the Peshawar Accords.[12][7]

But soon, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and his Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin again infiltrated Kabul trying to take power. This forced other parties to advance on the capital as well. Already before 28 April, the Mujahideen forces that had fought against Russian troops with help from the US had taken command of Kabul and Afghanistan.[8] Hekmatyar had asked other groups such as Harakat-Inqilab-i-Islami and the Khalis faction to join him while entering Kabul, but they declined his offer and instead backed the Peshawar Accords. Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin entered the city from the south and west but were quickly expelled. The forces of Jamiat-e Islami and Shura-e Nazar entered the city, with agreement from Nabi Azimi and the Commander of the Kabul Garrison, General Abdul Wahid Baba Jan that they would enter the city through Bagram, Panjshir, Salang and Kabul Airport.[55] Many government forces, including generals, joined Jamiat-e Islami,[55] including the forces of General Baba Jan, who was at the time in charge of the garrison of Kabul. On 27 April, all other major parties such as Junbish-i Milli, Hezb-i Wahdat, Ittehad-e Islami and Harakat had entered the city as well.[23] After suffering heavy casualties, Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin forces deserted their positions and fled to the outskirts of Kabul in the direction of Logar province.

The Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin had been driven out of Kabul, but were still within artillery range. In May 1992 Hekmatyar started a bombardment campaign against the capital, firing thousands of rockets supplied by Pakistan.[10] In addition to the bombardment campaign, Hekmatyar's forces had overrun Pul-e-Charkhi prison while still in the centre of Kabul, and had set free all the inmates, including many criminals, who were able to take arms and commit gruesome crimes against the population.[56] With a government structure yet to be established, chaos broke out in Kabul.

The immediate objective of the interim government was to defeat the forces acting against the Peshawar Accord. A renewed attempt at peace talks on 25 May 1992 again agreed to give Hekmatyar the position of prime minister, however, this lasted less than a week after Hekmatyar attempted to shoot down the plane of President Mujaddidi.[23] Furthermore, as part of the peace talks Hekmatyar was demanding the departure of Dostum's forces, which would have tilted the scales in his favour.[23] This led to fighting between Dostum and Hekmatyar. On 30 May 1992, during fighting between the forces of Dostum's Junbish-i Milli and Hekmatyar's Hizb-i Islami in the southeast of Kabul, both sides used artillery and rockets, killing and injuring an unknown number of civilians.[55]

June–July

[edit]In June 1992, as scheduled in the Peshawar Accords, Burhanuddin Rabbani became interim president of Afghanistan.

From the onset of the battle, Jamiat-e Islami and Shura-e Nazar controlled the strategic high areas, and were thus able to develop a vantage point within the city from which opposition forces could be targeted. Hekmatyar continued to bombard Kabul with rockets. Although Hekmatyar insisted that only Islamic Jihad Council areas were targeted, the rockets mostly fell over the houses of the innocent civilians of Kabul, a fact that has been well-documented.[23][57] Artillery exchanges quickly broke out escalating in late May–Early June. Shura-e Nazar was able to immediately benefit from heavy weapons left by fleeing or defecting government forces and launched rockets on Hekmatyar's positions near the Jalalabad Custom's Post, and in the districts around Hood Khil, Qala-e Zaman Khan and near Pul-e-Charkhi prison. On 10 June it was reported that Dostum's forces had also begun nightly bombardments of Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin positions.[16]

Particularly noticeable in this period was the escalation of the fight in West Kabul between the Shi'a Hezb-i Wahdat forces supported by Iran and those of the Wahhabist Ittehad-e Islami militia supported by Saudi Arabia. Hezb-i Wahdat was somewhat nervous about the presence of Ittehad-e Islami posts, which were deployed in Hazara areas such as Rahman Baba High school. According to the writings of Nabi Azimi, who at the time was a high ranking governor, the fighting began on 31 May 1992 when 4 members of Hezb-i Wahdat's leadership were assassinated near the Kabul Silo. Those killed were Karimi, Sayyid Isma'il Hosseini, Chaman Ali Abuzar and Vaseegh, the first 3 being members of the party's central committee. Following this the car of Haji Shir Alam, a top Ittehad-e Islami commander was stopped near Pol-e Sorkh, and although Alem escaped, one of the passengers was killed.[58] On 3 June 1992, heavy fighting between forces of Ittehad-e Islami and Hezb-i Wahdat in west Kabul. Both sides used rockets, killing and injuring civilians. On 4 June, interviews with Hazara households state that Ittehad-e Islami forces looted their houses in Kohte-e Sangi, killing 6 civilians. The gun battles at this time had a death toll of over 100 according to some sources.[59] On 5 June 1992, further conflict between forces of Ittehad-e Islami and Hezb-i Wahdat in west Kabul was reported. Here, both sides used heavy artillery, destroying houses and other civilian structures. Three schools were reported destroyed by bombardment. The bombardment killed and injured an unknown number of civilians. Gunmen were reported killing people in shops near the Kabul Zoo. On 24 June 1992 the Jamhuriat hospital located near the Interior Ministry was bombed and closed. Jamiat-e Islami and Shura-e Nazar sometimes joined the conflict when their positions came under attack by Hezb-i Wahdat forces and in June/July bombarded Hezb-i Wahdat positions in return. Harakat forces also sometimes joined the fight.[citation needed]

August–December

[edit]In the month of August alone, a bombardment of artillery shells, rockets and fragmentation bombs killed over 2,000 people in Kabul, most of them civilians. On 1 August the airport was attacked by rockets. 150 rockets alone were launched the following day, and according to one author these missile attacks killed as many as 50 people and injured 150. In the early morning on 10 August Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin forces attacked from three directions – Chelastoon, Darulaman and Maranjan mountain. A shell also struck a Red Cross hospital. On 10–11 April[clarification needed] nearly a thousand rockets hit parts of Kabul including about 250 hits on the airport. Some estimate that as many as 1000 were killed, with the attacks attributed to Hekmatyar's forces.[16] By 20 August it was reported that 500, 000 people had fled Kabul.[60] On 13 August 1992, a rocket attack was launched on Deh Afghanan in which cluster bombs were used. 80 were killed and more than 150 injured according to press reports. In response to this, Shura-e Nazar forces bombard Kart-I Naw, Shah Shaheed and Chiilsatoon with aerial and ground bombardment. In this counterattack more than 100 were killed and 120 wounded.[23]

Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin was not however the only perpetrator of indiscriminate shelling of civilians. Particularly in West Kabul, Hezb-i Wahdat, Ittehad-e Islami and Jamiat-e Islami all have been accused of deliberately targeting civilian areas.[citation needed] All sides used non-precision rockets such as Sakre rockets and the UB-16 and UB-32 S-5 airborne rocket launchers.

In November, in a very effective move, Hekmatyar's forces, together with guerrillas from some of the Arab groups, barricaded a power station in Sarobi, 30 miles east of Kabul, cutting electricity to the capital and shutting down the water supply, which is dependent on power. His forces and other Mujahideen were also reported to have prevented food convoys from reaching the city.[citation needed]

On 23 November, Minister of Food Sulaiman Yaarin reported that the city's food and fuel depots were empty. The government was now under heavy pressure. At the end of 1992 Hezb-i Wahdat officially withdrew from the government and opened secret negotiations with Hizb-I Islami. In December 1992, Rabbani postponed convening a shura to elect the next president. On 29 December 1992, Rabbani was elected as president and he agreed to establish a parliament with representatives from all of Afghanistan. Also notable during this month was the solidification of an alliance between Hezb-i Wahdat and Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin against the Islamic State of Afghanistan. While Hizb-i Islami joined in bombardments to support Hezb-i Wahdat, Wahdat conducted joint offensives, such as the one to secure Darulaman.[61] On 30 December 1992 at least one child was apparently killed in Pul-i Artan by a BM21 Rocket launched from Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin forces at Rishkor.[62]

Kandahar

[edit]Kandahar was host to three different local Pashtun commanders Amir Lalai, Gul Agha Sherzai and Mullah Naqib Ullah who engaged in an extremely violent struggle for power and who were not affiliated with the interim government in Kabul. The bullet-riddled city came to be a centre of lawlessness, crime and atrocities fueled by complex Pashtun tribal rivalries.[citation needed]

1993

[edit]January–February

[edit]The authority of Burhanuddin Rabbani, interim President since June 1992 and also the leader of the Jamiat-e Islami party, remained limited to only part of Kabul; the rest of the city remained divided among rival militia factions. On 19 January, a short-lived cease-fire broke down when Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin forces renewed rocket attacks on Kabul from their base in the south of the city supervised by Commander Toran Kahlil.[63] Hundreds were killed and wounded while many houses were destroyed in this clash between Hizb-i Islami and Jamiat-e Islami.[citation needed]

Heavy fighting was reported around a Hezb-i Wahdat post held by Commander Sayid Ali Jan near Rabia Balkhi girls' school. Most notable during this period was the rocket bombardments that would start against the residential area of Afshar. Some of these areas, such as Wahdat's headquarters at the Social Science Institute, were considered military targets, a disproportionate number of the rockets, tank shells and mortars fell in civilian areas.[64] Numerous rockets were reportedly launched from Haider-controlled frontlines of Tap-I Salaam towards the men of Division 095 under Ali Akbar Qasemi. One attack during this time from Hezb-i Wahdat killed at least 9 civilians.[65] Further rockets bombardments took place on 26 February 1993 as Shura-e Nazar and Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin bombarded each other's positions. Civilians were the main victims in the fighting, which killed some 1,000 before yet another peace accord was signed on 8 March. However the following day rocketing by Hekmatyar's Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin and Hezb-i Wahdat in Kabul left another 10 dead.[66]

Afshar

[edit]See the main article for more information:

The Afshar Operation was a military operation by Burhanuddin Rabbani's Islamic State of Afghanistan government forces against Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin and Hezb-i Wahdat forces that took place in February 1993. The Iran-controlled Hezb-i Wahdat together with the Pakistani-backed Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin of Hekmatyar were shelling densely populated areas in Kabul from their positions in Afshar. To counter these attack Islamic State forces attacked Afshar in order to capture the positions of Wahdat, capture Wahdat's leader Abdul Ali Mazari and to consolidate parts of the city controlled by the government. The operation took place in a densely populated district of Kabul, the Afshar district. Afshar district is situated on the slopes of Mount Afshar in west Kabul. The district is predominantly home to the Hazara ethnic group. The Ittehad-e Islami troops of Abdul Rasul Sayyaf escalated the operation into a rampage against civilians. Both Ittehad and Wahdat forces have severely targeted civilians in their war. The Wahhabist Ittehad-e Islami supported by Saudi Arabia was targeting Shias, while the Iran-controlled Hezb-i Wahdat was targeting Sunni Muslims.[citation needed]

March–December

[edit]

Under the March accord, brokered by Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, Rabbani and Hekmatyar agreed to share power until elections could be held in late 1994. Hekmatyar's condition had been the resignation of Massoud as minister of defense. The parties agreed to a new peace accord in Jalalabad on 20 May under which Massoud agreed to relinquish the post of Defense Minister. Massoud had resigned in order to gain peace.[citation needed] Hekmatyar at first accepted the post of prime minister but after attending only one cabinet meeting he left Kabul again starting to bomb Kabul leaving more than 700 dead in bombing raids, street battles and rocket attacks in and around Kabul. Massoud returned to the position of minister of defense to defend the city against the rocket attacks.[citation needed]

1994

[edit]January–June

[edit]In January 1994, Dostum, for different reasons, joined with the forces of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin, along with their new allies of Hezb-i Wahdat and Junbish-i Milli, launched the Shura Hamaghangi campaign against the forces of Massoud and the interim government. During this, Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin was able make use of Junbish's air force in both bombing the positions of Jamiat-e Islami and in resupplying their men. This led to greater artillery bombardment on behalf of Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin.[57] Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin and Junbish-i Milli were able to hold parts of central Kabul during this time. Junbish forces were particularly singled out for committing looting, rape and murder, for the sole reason that they could get away with it.[67] Some commanders such as Shir Arab, commander of the 51st regiment,[57] Kasim Jangal Bagh, Ismail Diwaneh ["Ismail the Mad"], and Abdul Cherikwere[23] particularly singled out. According to Afghanistan Justice Project, during this period until June 1994, 25,000 people were killed. Areas around Microraion were particularly bloody. By now the population of Kabul had dropped from 2,000,000 during Soviet times to 500,000 due to a large exodus from Kabul.[68]

July–December

[edit]According to Human Rights Watch, numerous Iranian agents were assisting Hezb-i Wahdat, as "Iran was attempting to maximize Wahdat's military power and influence in the new government".[10][23][69] Saudi agents "were trying to strengthen the Wahhabi Abdul Rasul Sayyaf and his Ittehad-e Islami faction to the same end".[10][23] "Outside forces saw instability in Afghanistan as an opportunity to press their own security and political agendas."[45] Human Rights Watch writes that "rare ceasefires, usually negotiated by representatives of Ahmad Shah Massoud, Sibghatullah Mojaddedi or Burhanuddin Rabbani (the interim government), or officials from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), commonly collapsed within days."[23]

The Taliban movement first emerged on the military scene in August 1994,[citation needed] with the stated goal of liberating Afghanistan from its present corrupt leadership of warlords and establish a pure Islamic society. It was reported in the December 2009 edition of Harper's Weekly that the Taliban originated in the districts around Kandahar city.[70] By October 1994 the Taliban movement had according to academic consensus and on-the-ground reports attracted the support of Pakistan[71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78] which saw in the Taliban a way to secure trade routes to Central Asia and establish a government in Kabul friendly to its interests.[79][80][81][82] Pakistani politicians during that time repeatedly denied supporting the Taliban.[47][83] But senior Pakistani officials such as Interior Minister Naseerullah Babar would later state, "we created the Taliban"[49] and former Pakistani President Musharraf would write "we sided" with the Taliban to "spell the defeat" of anti-Taliban forces.[50]

In October 1994 a bomb struck a wedding ceremony in Qala Fathullah in Kabul, killing 70 civilians. No fighting had been witnessed in the area in several days according to reports.[84]

Also in October 1994, the Taliban revolted in Kandahar. On 12 October 1994, the Taliban scored their first victory when they captured the Kandahar district of Spin Boldak.[70] They then captured Kandahar city on 5 November 1994 and soon went on to capture most of the south.

By the end of 1994, Junbish-i Milli and Dostum were on the defensive in capital Kabul, and Massoud's forces had ousted them from most of their strongholds. Massoud more and more gained control of Kabul. At the same time Junbish was able to push Jamiat-e Islami out of Mazar-e Sharif.

1995

[edit]January–March

[edit]Interim President Rabbani refused to step down at the end of his term on 28 December 1994, and on 1 January UN peace envoy Mahmoud Mistiri returned to Kabul.[6] On 10 January Rabbani offered to step down and turn over power to a 23-member UN interim administration if Hikmatyar agreed to withdraw. On 12 January a cease fire was agreed, but bombing began again on 19 January, killing at least 22.[6] Between 22 and 31 January, Dostum's Junbish-i Milli party bombed government positions in Kunduz town and province, killing 100 people are and wounding over 120. The town fell to Dostum on 5 February. Rabbani further delayed his resignation on the 21st, stating he would resign on the 22nd.[6] In late January, Ghazni fell to the Taliban. Hikmatyar lost hundreds of men and several tanks in the battle, which included a temporary alliance between the Taliban and the forces of Rabbani.[6]

Meanwhile, the Taliban began to approach Kabul, capturing Wardak in early February and Maidan Shar, the provincial capital, on 10 February 1995. On 14 February 1995, Hekmatyar was forced to abandon his artillery positions at Charasiab due to the advance of the Taliban, who were, therefore, able to take control of this weaponry. During 25–27 February clashes broke out in Karte Seh, Kote Sangi and Karte Chahar between government forces and Hezb-i Wahdat, resulting in 10 dead and 12 wounded.[6] In March, Massoud launched an offensive against Hezb-i Wahdat trapping Wahdat forces in Karte Seh and Kote Sangi. According to other reports, the forces of Jamiat-e Islami also committed mass rape and executions on civilians in this period.[85] The Taliban retreated under the bombardment, taking Mazari with them and throwing him from a helicopter en route to Kandahar. The Taliban then continued to launch offenses against Kabul, using the equipment of Hizb-e Islami. While the Taliban retreated, large amounts of looting and pillaging was said to have taken place in south-western Kabul by the forces under Rabbani and Massoud against ethnic Hazaras.[86] Estimates of civilian casualties from this period of fighting are 100 killed and 1000 wounded.[6]

Starting on 12 March 1995 Massoud's forces launched an offensive against the Taliban and were able to drive them out from the area around Kabul, retaking Charasiab on 19 March and leading to a period of relative calm for a few months. The battle left hundreds of Taliban dead and the force suffered its first defeat. However, while retreating, the Taliban shelled the capital, Kabul. On 16 March, Rabbani stated, once again, that he would not resign. On 30 March, a grave of 22 male corpses, 20 of which were shot in the head, was found in Charasiab.[6]

April–September

[edit]On 4 April, the Taliban killed about 800 government soldiers and captured 300 more in Farah Province, but were later forced to retreat.[6] In early May, Rabbani's forces attacked the Taliban in Maidan Shar.[6] India and Pakistan agree to reopen their diplomatic missions in Kabul on 3–4 May. On 11 May, Ismail Khan and Rabbani's forces recaptured Farah from the Taliban. Ismail Khan reportedly used cluster bombs, killing 220–250 unarmed civilians.[6] Between 14 and 16 May, Helmand and Nimruz fall to Rabbani and Khan's forces. On 20 May, Hezb-i Wahdat forces captured Bamiyan. On 5 June, Dostum's forces attacked Rabbani's forces in Samangan. More than 20 are killed, and both forces continue to fight in Baghlan. On 9 June, a 10-day truce was signed between the government and the Taliban. On 15 June, Dostum bombed Kabul and Kunduz. Two 550-pound (250 kg) bombs are dropped in a residential area of Kabul, killing two and injuring one. Three land near the defence ministry.[6] On 20 June, the government recaptured Bamiyan. On 23 July, Dostum and Wahdat managed to recapture Bamiyan. On 3 August, the Taliban hijacked a Russian cargo aircraft in Kandahar and captured weapons intended for Rabbani. The Government captured Girishk and Helmand from the Taliban on 28 August, but were unable to hold Girishk. In September, Dostum forces captured Badghis. The Taliban were able to capture Farah on 2 September, and Shindand on the 3rd. On 5 September, Herat fell, with Ismail Khan fleeing to Mashhad. Some attribute this to the informal alliance between Dostum and the Taliban, along with Dostum's bombing of the city.[6] Iran followed by closing the border. On 6 September, a mob swarms the Pakistani embassy in Kabul, killing one and wounding 26, including the Pakistani ambassador.

October–December

[edit]On 11 October, the Taliban retook Charasiab. The National Reconciliation Commission presented its proposals for peace on the same day. On 15 October, Bamiyan fell to the Taliban. Between 11 and 13 November 1995 at least 57 unarmed civilians were killed and over 150 injured when rockets and artillery barrages fired from Taliban positions south of Kabul pounded the civilian areas of the city. On 11 November alone, 36 civilians were killed when over 170 rockets as well as shells hit civilians areas. A salvo crashed into Foruzga Market, while another struck the Taimani district, where many people from other parts of Kabul have settled. Other residential areas hit by artillery and rocket attacks were the Bagh Bala district in the northwest of Kabul and Wazir Akbar Khan, where much of the city's small foreign community lived.[53] In the north, Rabbani's forces fought for control of the Balkh Province, reclaiming many districts from Dostum.

On 20 November 1995, Taliban forces gave the government a 5-day ultimatum in which they would resume bombardment if Rabbani and his forces did not leave the city. This ultimatum was eventually withdrawn.[53] By the end of December, more than 150 people had died in Kabul due to the repeated rocketing, shelling, and high-altitude bombing of the city, reportedly by Taliban forces.[86]

1996

[edit]January–September

[edit]On 2–3 January, Taliban rocket attacks killed between 20 and 24 people and wounded another 43–56.[6] On 10 January, a peace proposal was presented to the Taliban and opposition. On 14, January Hikmatyar blocked Kabul's western route, leaving the city surrounded. However, in mid-January, Iran intervened and the Khalili faction of Hezb-i Wahdat signed a peace agreement that lead to the opening of the Kabul-Bamiyan road. On 20 January, factional fighting broke out among the Taliban in Kandahar. On 1 February, Taliban jet-bombed a residential area in Kabul, killing 10 civilians. On 3 February, the Red Cross began to airlift supplies into Kabul.[6] On 6 February, the road is used to bring in more food. On 26 February, Hikmatyar and the pro-Dostum Ismaili faction of Sayed Jafar Nadiri fought in Pul-i Khumri, Baghlan Province. Hundreds were killed before a ceasefire was reached on 4 March and the Ismaili faction lost 11 important positions.[6]

In 1996, the Taliban returned to seize Kabul.[87] Analyst Ahmed Rashid considers the Taliban at that time to have been decisively supported by Pakistan;[citation needed] also less renowned sources suspect Taliban to have had support from Pakistan, considering their heavy weaponry.[54]

On 7 March, Hikmatyar and the Burhanuddin Rabbani government signed an agreement to take military action against the Taliban.

On 11 April, the government captured Saghar District in Ghor Province from the Taliban, along with large stores of ammunition. Fighting continues, however, in Chaghcharan, and the Taliban captured Shahrak district.[6] On 4 May, the Iranian embassy in Kabul was shelled and two staff members were wounded. On 12 May, Hikmatyar's forces arrived in Kabul to help defend against the Taliban. On 24 May, another peace agreement was signed between Rabbani and Hikmatyar. On 24 June, Rasul Pahlawan, an Uzbek military leader in Afghanistan, was killed in an ambush near Mazar-i Sharif. This would later have significant impact on the balance of power in the North.[citation needed]

On 3 July, a 10-member cabinet is formed. Hikmatyar's party got the ministries of defense and finance; Rabbani got the ministries of interior and foreign affairs; Sayyaf's party got education, information and culture, while Harakat-i-Islami got planning and labor and social welfare and the Hezb-i Wahdat Akbari faction got commerce. 12 other seats were left open for other factions.[6]

On 8 August government forces captured Chaghcharan, but lost it again. On 11 September, Jalalabad fell to the Taliban, who then marched on Sarobi. On 12 September, the Taliban captured Mihtarlam in Laghman province. On 22 September, Kunar province fell to the Taliban.[6]

Taliban take-over

[edit]

On 25 September, the strategic town[6] of Sarobi, an eastern outpost of Kabul, fell to the Taliban[88] who captured it from interim government troops.[6] 50 people were killed and the Taliban captured many arms from fleeing government soldiers.[6]

On 26 September, with the Taliban attacking Kabul,[6] interim minister of defense Ahmad Shah Massoud in his headquarters in northern Kabul concluded that his and President Rabbani's interim government's forces had been encircled,[88] and decided to quickly evacuate[88] or withdraw[6] those forces to the north,[88][6] to avoid destruction.[88] Also Hekmatyar, leader of Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin, withdrew from Kabul.[6]

By nightfall,[88] or on the next day of 27 September,[6] the Taliban had conquered Kabul.[88][6] Taliban's leader Mullah Muhammad Omar appointed his deputy, Mullah Mohammad Rabbani, as head of a national ruling council which was called the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.[6] By now, the Taliban controlled most of Afghanistan.[2]

Aftermath

[edit]In its first action while in power, the Taliban hung former President Najibullah and his brother from a tower, after they had first castrated Najibullah[89] and then tortured them to death.[citation needed] All key government installations appeared to be in Taliban's hands within hours, including the presidential palace and the ministries of defense, security and foreign affairs.

On 5 October 1996, the Taliban attacked Massoud's forces in the Salang Pass but suffered heavy losses. On 1 October, Massoud retook Jabal Saraj and Charikar. Bagram was taken back a week later. On 15–19 October, Qarabagh changed hands before being captured by Massoud and Dostum's forces.[6] During 21–30 October, Massoud's forces stalled on the way to the capital. On 25 October, the Taliban claimed to have captured Badghis province and started to attack Dostum's forces in Faryab. On 27–28 October, anti-Taliban forces attempted to recapture Kabul but were unable to do so. On 30 October Dara-I-Nur District in Nangarhar province fell to anti-Taliban forces but was retaken in early November. Fighting also occurred in Baghdis province with no significant gains from either side. Ismail Khan's forces were flown in from Iran to support the anti-Taliban alliance. On 4 November, Dostum's forces bombed the Herat airport and anti-Taliban forces took control of Nurgal district in Konar province. Between 9 and 12 November, Dostum's jets bombed the Kabul airport, and between 11 and 16 approximately 50,000 people, mostly Pashtuns, arrived in Herat province, fleeing the fight in Badghis. On 20 November, the UNHCR halted all activities in Kabul. On 21–22 December, anti-Taliban demonstrations occurred in Herat as women demanded assistance from international organizations, but it was violently dispersed. On 28–29 December a major offensive was launched against Bagram airbase and the base was surrounded.[6]

The United Front, known in the Pakistani and Western media as the 'Northern Alliance', was created in opposition to the Taliban under the leadership of Massoud. In the following years, over 1 million people fled the Taliban, many arriving to the areas controlled by Massoud. The events of this war lead to the Afghan Civil War (1996–2001).

References

[edit]- ^ Maley, William (2002), Maley, William (ed.), "The Interregnum of Najibullah, 1989–1992", The Afghanistan Wars, London: Macmillan Education UK, p. 193, doi:10.1007/978-1-4039-1840-6_9, ISBN 978-1-4039-1840-6, retrieved 27 December 2022

- ^ a b Country profile: Afghanistan (published August 2008) Archived 11 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine (page 3). Library of Congress. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ See sections Bombardments and Timeline 1994, Januari-June

- ^ See section Bombardments

- ^ See sections Atrocities and Timeline

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Afghanistan: Chronology of Events January 1995 – February 1997 (PDF) (Report). Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. February 1997. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ a b Sifton, John (6 July 2005). Blood-Stained Hands: Past Atrocities in Kabul and Afghanistan's Legacy of Impunity (chapter II, Historical background) (Report). Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ a b Urban, Mark (28 April 1992). "Afghanistan: power struggle". PBS. Archived from the original on 9 July 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- ^ a b c Sifton, John (6 July 2005). Blood-Stained Hands: Past Atrocities in Kabul and Afghanistan's Legacy of Impunity (ch. III, Battle for Kabul 1992-93) (Report). Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Saikal (2004), p. 352.

- ^ [dead link] Kent, Arthur (9 September 2007). "Warnings About al Qaeda Ignored by the West". SKY Reporter. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013.

- ^ a b "The Peshawar Accord, April 25, 1992" Archived 4 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Website photius.com. Text from 1997, purportedly sourced on The Library of Congress Country Studies (USA) and CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ a b c For details and reference sources see section 'Timeline' below

- ^ a b c d "Afghanistan: The massacre in Mazar-i Sharif. (Chapter II: Background)". Human Rights Watch. November 1998. Archived from the original on 2 November 2008. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Sifton, John (6 July 2005). Blood-Stained Hands: Past Atrocities in Kabul and Afghanistan's Legacy of Impunity (ch. III, Battle for Kabul 1992-93; see under § Violations of International Humanitarian Law) (Report). Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d Jamilurrahman, Kamgar (2000). Havadess-e Tarikhi-e Afghanistan 1990–1997. Peshawar Markaz-e Nashrati. translation by Human Rights Watch. Meyvand. pp. 66–68.

- ^ a b c 'The Taliban' Archived 17 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University. Updated 15 July 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ^ See reference sources in Taliban#Role of the Pakistani military and Taliban#Pakistan

- ^ Clements, Frank (2003). "Civil War". Conflict in Afghanistan: A Historical Encyclopedia Roots of Modern Conflict. ABC-CLIO. p. 49. ISBN 9781851094028. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ "A Decade Ago, Massoud's Killing Preceded Sept. 11". NPR.org. NPR.org. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ^ "Mujahedin Victory Event Falls Flat". Danish Karokhel. 5 April 2003. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014.

- ^ Dorronsoro, Gilles (14 October 2007). "Kabul at War (1992–1996) : State, Ethnicity and Social Classes". Gilles Dorronsoro. doi:10.4000/samaj.212. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Sifton, John (6 July 2005). Blood-Stained Hands: Past Atrocities in Kabul and Afghanistan's Legacy of Impunity (Report). Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ a b c "Ittihad". Blood-Stained Hands: Past Atrocities in Kabul and Afghanistan's Legacy of Impunity. Human Rights Watch. 2005. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ Anderson, John Lee (2002). The Lion's Grave (26 November 2002 ed.). Atlantic Books. p. 224. ISBN 1-84354-118-1.

- ^ Phil Rees (2 December 2001). "A personal account". BBC News. Archived from the original on 21 December 2008. Retrieved 21 April 2008.

- ^ "Pakistan Pleads for Cease-Fire in Afghanistan". The New York Times. 27 August 1992. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ "Afghan Peace Mission". The Independent UK. London. 26 August 1992. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- ^ Marsden, Peter (15 September 1998). The Taliban: War, Religion and the New Order in Afghanistan. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781856495226. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ a b "Blood-Stained Hands, Past Atrocities in Kabul and Afghanistan's Legacy of Impunity". Human Rights Watch. 6 July 2005. Archived from the original on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ a b Amin Saikal (2006). Modern Afghanistan: A History of Struggle and Survival (1st ed.). London New York: I.B. Tauris & Co. p. 352. ISBN 1-85043-437-9.

- ^ Gutman, Roy (2008): How We Missed the Story: Osama Bin Laden, the Taliban and the Hijacking of Afghanistan, Endowment of the United States Institute of Peace, 1st ed., Washington DC.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Blood-Stained Hands: III. The Battle for Kabul: April 1992-March 1993". Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Blood-Stained Hands: III. The Battle for Kabul: April 1992-March 1993". Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Blood-Stained Hands: III. The Battle for Kabul: April 1992-March 1993". Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ Vogelsang (2002), p. 324.

- ^ a b "Abdul Rashid Dostum". Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. Archived from the original on 10 March 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- ^ Anthony Davis, 'The Battlegrounds of Northern Afghanistan,' Jane's Intelligence Review, July 1994, p.323-4

- ^ Vogelsang (2002), p. 232.

- ^ The Last Warlord: The Life and Legend of Dostum, the Afghan Warrior Who Led US Special Forces to Topple the Taliban Regime by Brian Glyn Williams, 2013

- ^ Tomsen, Peter (2011). The Wars of Afghanistan: Messianic Terrorism, Tribal Conflicts, and the Failures of Great Powers. PublicAffairs. pp. 405–408. ISBN 978-1-58648-763-8. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ^ 'The Rise of the Taliban' (etc.) Archived 27 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Amazon. Retrieved 14 January 2018. N.B.: The relevance of this web page lies in the two 'Editorial Reviews' which suggest that mr. Nojumi is not held in great respect among acknowledged historians.

- ^ Nojumi (2002), p. 260.

- ^ Shaffer, Brenda (2006). The Limits of Culture: Islam and Foreign Policy. MIT Press. p. 267. ISBN 978-0-262-19529-4. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

Pakistani involvement in creating the movement is seen as central

- ^ a b Gandhi, Sajit, ed. (11 September 2003). "The September 11th Sourcebooks, Volume VII: The Taliban File". National Security Archive. George Washington University. Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ Coll (2004), p. 5 and 13.

- ^ a b Hussain, Rizwan (2005). Pakistan and the Emergence of Islamic Militancy in Afghanistan. Ashgate. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-7546-4434-7.

- ^ Aziz, Omer (8 June 2014). "The ISI's Great Game in Afghanistan". The Diplomat – The Diplomat is a current-affairs magazine for the Asia-Pacific, with news and analysis on politics, security, business, technology and life across the region. Archived from the original on 8 October 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ a b McGrath, Kevin (2011). Confronting Al-Qaeda: New Strategies to Combat Terrorism. Naval Institute Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-61251-033-0.

- ^ a b Musharraf, Pervez (2006). In the Line of Fire: A Memoir. Simon and Schuster. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-7432-9843-8.

- ^ Maley, William (2009). The Afghanistan Wars: Second Edition. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 288. ISBN 978-1-137-23295-3.

- ^ "Casting Shadows: War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity: 1978–2001" (PDF). Afghanistan Justice Project. 2005. p. 63. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Afghanistan: Further Information on Fear for Safety and New Concern: Deliberate and Arbitrary Killings: Civilians in Kabul (Report). Amnesty International. 16 November 1995. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ^ a b Video 'Starving to Death', Massoud defending Kabul against the Taliban siege in March 1996. Archived 13 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine (With horrifying pictures of civilian war casualties.) By Journeyman Pictures/Journeyman.tv. Retrieved on YouTube, 27 June 2018.

- ^ a b c Afghanistan Justice Project (2005), p. 65.

- ^ De Ponfilly, Christophe (2001). Massoud l'Afghan. Gallimard. p. 405. ISBN 2-07-042468-5.

- ^ a b c Afghanistan Justice Project (2005).

- ^ Mohammaed Nabi Azimi, "Ordu va Siyasat." p 606.[full citation needed]

- ^ Herbaugh, Sharon (5 June 1992). "Pro-Government militias intervene as fighting continues in Kabul". Associated Press.

- ^ Bruno, Philip (20 August 1992). "La seconde bataille de Kaboul 'le gouvernment ne contrôle plus rien". Le Monde.

- ^ Afghanistan Justice Project (2005), p. 71.

- ^ Afghanistan Justice Project (2005), p. 76.

- ^ Afghanistan Justice Project (2005), p. 67.

- ^ Afghanistan Justice Project (2005), p. 77.

- ^ Afghanistan Justice Project (2005), p. 78.

- ^ Afghanistan Justice Project (2005), p. 79.

- ^ Afghanistan Justice Project (2005), p. 105.

- ^ "The Struggle for Kabul" Library of Congress Country Studies Archived 9 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gutman (2008).

- ^ a b Aikins, Matthieu (December 2009). "The Master of Spin Boldak: Meet the mobsters who run the show in one of the world's deadliest cities". Harper's Magazine. Vol. December 2009. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ Shaffer, Brenda (2006). The Limits of Culture: Islam and Foreign Policy. MIT Press. p. 267. ISBN 978-0-262-19529-4.

Pakistani involvement in creating the movement is seen as central

- ^ Forsythe, David P (2009). Encyclopedia of Human Rights. Vol. 1: Afghanistan-Democracy and the Right to Participate. Oxford University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-19-533402-9.

In 1994 the Taliban was created, funded and inspired by Pakistan

- ^ Gardner, Hall (2007). American Global Strategy and the 'War on Terrorism'. Ashgate. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-4094-9589-5.

- ^ Jones, Owen Bennett (2003). Pakistan: Eye of the Storm. Yale University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-300-10147-8.

The ISI's undemocratic tendencies are not restricted to its interference in the electoral process. The organisation also played a major role in creating the Taliban movement.

- ^ Randal, Jonathan C. (2012). Osama: The Making of a Terrorist. I.B.Tauris. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-78076-055-1.

Pakistan had all but invented the Taliban, the so-called Koranic students

- ^ Peimani, Hooman (2003). Falling Terrorism and Rising Conflicts: The Afghan "Contribution" to Polarization and Confrontation in West and South Asia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-275-97857-0.

Pakistan was the main supporter of the Taliban since its military intelligence, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) formed the group in 1994

- ^ Hilali, A. Z. (2005). US-Pakistan Relationship: Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan. Ashgate. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-7546-4220-6.

- ^ Rumer, Boris Z. (2015). Central Asia: A Gathering Storm?. Taylor & Francis. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-317-47521-7.

- ^ Pape, Robert A.; Feldman, James K. (2010). Cutting the Fuse: The Explosion of Global Suicide Terrorism and How to Stop It. University of Chicago Press. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-0-226-64564-3.

- ^ Harf, James E.; Lombardi, Mark Owen (2005). The Unfolding Legacy of 9/11. University Press of America. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-7618-3009-2.

- ^ Hinnells, John; King, Richard (2007). Religion and Violence in South Asia: Theory and Practice. Routledge. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-134-19219-9.

- ^ Boase, Roger (2016). Islam and Global Dialogue: Religious Pluralism and the Pursuit of Peace. Routledge. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-317-11262-4.

Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence agency used the students from these madrassas, the Taliban, to create a favourable regime in Afghanistan

- ^ Saikal (2004), p. 342.

- ^ Women in Afghanistan: A Human Rights Catastrophe (Report). Amnesty International. 17 May 1994. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ Afghanistan Justice Project (2005), p. 63.

- ^ a b "Afghanistan Human Rights Practices, 1995". U.S. Department of State. March 1996. Archived from the original on 11 July 2010. Retrieved 7 December 2009.

- ^ Maley, William (1998). Fundamentalism Reborn?: Afghanistan and the Taliban. New York University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-8147-5586-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g Coll (2004), p. 14.

- ^ Lamb, Christina (29 June 2003). "President of hell: Hamid Karzai's battle to govern post-war, post-Taliban Afghanistan". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015.

Bibliography

[edit]- Rashid, A. (2000). Taliban: Islam, oil, and the new great game in Central Asia. I.B. Tauris.

- Rubin, B. R. (2002). The fragmentation of Afghanistan: State formation and collapse in the international system. Yale University Press.

- Marsden, P. (1998). The Taliban: war, religion and the new order in Afghanistan. Zed Books.

- Casting Shadows: War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity: 1978-2001 (PDF) (Report). Afghanistan Justice Project. 2005.

- Coll, Steve (2004). Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001. Penguin Group, London, New York etc. ISBN 0-141-02080-6.

- Corwin, Phillip (2003). Doomed in Afghanistan: A UN Officer's Memoir of the Fall of Kabul and Najibullah's Failed Escape, 1992. Rutgers University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-8135-3171-7.

- Gutman, Roy (2008). How We Missed the Story: Osama Bin Laden, the Taliban, and the Hijacking of Afghanistan. US Institute of Peace Press. ISBN 978-1-60127-024-5.

- Nojumi, Neamatollah (2002). The Rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan: Mass Mobilization, Civil War, and the Future of the Region. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-29584-4.

- Saikal, Amin (2004). Modern Afghanistan: A History of Struggle and Survival. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85771-478-7.

External links

[edit]- Afghanistan – the Squandered Victory by the BBC (documentary film directly from the year 1989 explaining the beginning of the turmoil to follow)

- Massoud's Conversation with Hekmatyar (original document from 1992)

- Commander Massoud's Struggle by Nagakura Hiromi (from 1992, one month after the collapse of the communist regime, after Hekmatyar was repelled to the southern outskirts of Kabul, before he started the heavy bombardment of Kabul with the support of Pakistan)

- Starving to Death Afghanistan (documentary report) by Journeyman Pictures/ABC Australia (from March 1996)

- Afghan Civil War (1992–1996)

- Afghanistan conflict (1978–present)

- Battles involving Afghanistan

- Warlordism

- 20th century in Kabul

- 1990s in Afghanistan

- 1990s conflicts

- Conflicts in 1992

- Conflicts in 1993

- Conflicts in 1994

- Conflicts in 1995

- Conflicts in 1996

- Government of Benazir Bhutto

- Wars involving Afghanistan

- Wars involving the Taliban

- 1992 in Afghanistan

- 1993 in Afghanistan

- 1994 in Afghanistan

- 1995 in Afghanistan

- 1996 in Afghanistan

- Battles involving the Tajiks