Adamantane

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Adamantane[1]

| |||

| Other names

Tricyclo[3.3.1.13,7]decane

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.457 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C10H16 | |||

| Molar mass | 136.238 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | White to off-white powder | ||

| Density | 1.07 g/cm³ (20 °C), solid | ||

| Melting point | 270 °C (543 K) | ||

| Poorly soluble | |||

| Solubility in other solvents | Soluble in hydrocarbons | ||

| Structure | |||

| face-centred cubic | |||

| 0 D | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |||

Main hazards

|

Flammable | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

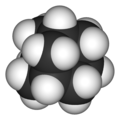

Adamantane (tricyclo[3.3.1.13,7]decane) is a colourless, crystalline compound with a camphor-like odour.[2] With a formula C10H16, it is a cycloalkane and also the simplest diamondoid. Adamantane was discovered in petroleum in 1933.[3] Its name derived from the Greek adamantinos (relating to steel or diamond), due to its diamond-like structure.[4] Adamantane is the most stable isomer of C10H16.

Synthesis

Adamantane was first synthesised by Prelog in 1941.[5][6] A more convenient method was found by Schleyer in 1957, from dicyclopentadiene by hydrogenation followed by acid-catalysed skeletal rearrangement.[7][8]

Uses

Adamantane itself enjoys few applications since it is merely an unfunctionalised hydrocarbon. It is used in some dry etching masks.[9] It is also used in some polymer formulations.

In solid-state NMR spectroscopy, adamantane is a common standard for chemical shift referencing.[10]

In dye lasers, adamantane may be used to extend the life of the gain medium; it cannot be photoionised under atmosphere because its absorption bands lie in the vacuum-ultraviolet region of the spectrum. Photoionization energies have been determined recently for adamantane as well as for several bigger diamondoids.[11]

Adamantane derivatives

Adamantane derivatives are useful in medicine, e.g. amantadine, memantine and rimantadine. Condensed adamantanes or diamondoids have been isolated from petroleum fractions, where they occur in small amounts. These species are of interest as molecular approximations of the cubic diamond framework, terminated with C-H bonds. 1,3-Dehydroadamantane is a member of the propellane family.

Due to its stability, specific steric properties and conformational rigidity, the 1-adamantyl group is a (bulky) substituent in organic and organometallic chemistry. Some of the first persistent carbenes featured adamantyl substituents.

Adamantane analogues

Many molecules adopt cage structures with adamantanoid structures. Particularly useful compounds with this motif include P4O6, As4O6, P4O10 (= (PO)4O6), P4S10 (= (PS)4S6), and N4(CH2)6.[12]

References

- ^ According to page 41 of a 2004 IUPAC guide, adamantane is the "preferred IUPAC name."

- ^ "ADAMANTANE(TRICYCLO(3.3.1.1)DECANE)". Retrieved 14 October 2005.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Landa, S.; Machácek, V. (1933). Collection Czech. Chem. Commun. 5: 1.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Alexander Senning. Elsevier's Dictionary of Chemoetymology. Elsevier, 2006. ISBN 0444522395.

- ^ Prelog, V., Seiwerth,R. (1941). "Über die Synthese des Adamantans". Berichte. 74: 1644–1648. doi:10.1002/cber.19410741004.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Prelog, V., Seiwerth,R. (1941). "Über eine neue, ergiebigere Darstellung des Adamantans". Berichte. 74: 1769–1772. doi:10.1002/cber.19410741109.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schleyer, P. von R. (1957). "A Simple Preparation of Adamantane". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 79: 3292–3292. doi:10.1021/ja01569a086.

- ^ Schleyer, P. von R.; Donaldson, M. M.; Nicholas, R. D.; Cupas, C. (1973). "Adamantane". Organic Syntheses

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collected Volumes, vol. 5, p. 16. - ^ Watanabe, Keiji; et al. (2001). "Resist Composition and Pattern Forming Process". United States Patent Application 20010006752. Bandwidth Market, Ltd. Retrieved 14 October 2005.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Morcombe, Corey R.; Zilm, Kurt W. (2003). "Chemical Shift referencing in MAS solid state NMR". J. Magn. Reson. 162: 479–486. doi:10.1016/S1090-7807(03)00082-X.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lenzke, K. ; Landt, L.; Hoener, M.; et al. (2007). "Experimental determination of the ionization potentials of the first five members of the nanodiamond series". J. Chem. Phys. 127: 084320. doi:10.1063/1.2773725.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vitall, J. J. (1996). "The Chemistry of Inorganic and Organometallic Compounds with Adamantane-Like Structures". Polyhedron. 15: 1585–1642. doi:10.1016/0277-5387(95)00340-1.