Adam and Eve

Adam and Eve, according to the creation myth[Note 1] of the Abrahamic religions,[1][2] were the first man and woman. They are central to the belief that humanity is in essence a single family, with everyone descended from a single pair of original ancestors.[3] They also provide the basis for the doctrines of the fall of man and original sin, which are important beliefs in Christianity, although not held in Judaism or Islam.[4]

In the Book of Genesis of the Hebrew Bible, chapters one through five, there are two creation narratives with two distinct perspectives. In the first, Adam and Eve are not named. Instead, God created humankind in God's image and instructed them to multiply and to be stewards over everything else that God had made. In the second narrative, God fashions Adam from dust and places him in the Garden of Eden. Adam is told that he can eat freely of all the trees in the garden, except for the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Subsequently, Eve is created from one of Adam's ribs to be his companion. They are innocent and unembarrassed about their nakedness. However, a serpent convinces Eve to eat fruit from the forbidden tree, and she gives some of the fruit to Adam. These acts not only give them additional knowledge, but also give them the ability to conjure negative and destructive concepts such as shame and evil. God later curses the serpent and the ground. God prophetically tells the woman and the man what will be the consequences of their sin of disobeying him. Then he banishes them from the Garden of Eden.

Neither Adam nor Eve is mentioned elsewhere in the Hebrew scriptures apart from a single listing of Adam in a genealogy in 1 Chronicles 1:1,[5] suggesting that although their story came to be prefixed to the Jewish story, it has little in common with it.[6] The myth underwent extensive elaboration in later Abrahamic traditions, and it has been extensively analyzed by modern biblical scholars. Interpretations and beliefs regarding Adam and Eve and the story revolving around them vary across religions and sects; for example, the Islamic version of the story holds that Adam and Eve were equally responsible for their sins of hubris, instead of Eve being the first one to be unfaithful. The story of Adam and Eve is often depicted in art, and it has had an important influence in literature and poetry.

Hebrew Bible narrative

The opening chapters of the Book of Genesis provide a mythic history of the infiltration of evil into the world.[7] God places the first man and woman (Adam and Eve) in his Garden of Eden, whence they are expelled; the first murder follows, and God's decision to destroy the world and save only the righteous Noah and his sons; a new humanity then descends from these and spreads throughout the world, but although the new world is as sinful as the old, God has resolved never again to destroy the world by flood, and the History ends with Terah, the father of Abraham, from whom will descend God's chosen people, the Israelites.[8]

Creation narrative

Adam and Eve are the Bible's first man and first woman.[9][10] Adam's name appears first in Genesis 1 with a collective sense, as "mankind"; subsequently in Genesis 2–3 it carries the definite article ha, equivalent to English 'the', indicating that this is "the man".[9] In these chapters God fashions "the man" (ha adam) from earth (adamah), breathes life into his nostrils, and makes him a caretaker over creation.[9] God next creates for the man an ezer kenegdo, a "helper corresponding to him", from his side or rib.[10] The word 'rib' is a pun in Sumerian, as the word ti means both 'rib' and 'life'.[11][12] She is called ishsha, "woman", because, the text says, she is formed from ish, "man".[10] The man receives her with joy, and the reader is told that from this moment a man will leave his parents to "cling" to a woman, the two becoming one flesh.[10]

The Fall

The first man and woman are in God's Garden of Eden, where all creation is vegetarian and there is no violence. They are permitted to eat the fruits of all the trees except one, the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. The woman is tempted by a talking serpent to eat the forbidden fruit, and gives some to the man, who eats also.[10] (Contrary to popular myth she does not beguile the man, who appears to have been present at the encounter with the serpent).[10] God punishes the man with a lifetime of hard labor followed by death, the woman with the pain of childbirth and subordination to her husband, and curses the serpent to crawl on its belly and endure enmity with both man and woman. God then clothes the nakedness of the man and woman, who have become god-like in knowing good and evil, then banishes them from the garden lest they eat the fruit of a second tree, the tree of life, and live forever.[13]

Expulsion from Eden

The story continues in Genesis 3 with the "expulsion from Eden" narrative. A form analysis of Genesis 3 reveals that this portion of the story can be characterized as a parable or "wisdom tale" in the wisdom tradition. The poetic addresses of the chapter belong to a speculative type of wisdom that questions the paradoxes and harsh realities of life. This characterization is determined by the narrative's format, settings, and the plot. The form of Genesis 3 is also shaped by its vocabulary, making use of various puns and double entendres.[14]

The expulsion from Eden narrative begins with a dialogue between the woman and a serpent,[15] identified in Genesis 3:1[16] as an animal that was more crafty than any other animal made by God, although Genesis does not identify the serpent with Satan.[17] The woman is willing to talk to the serpent and respond to the creature's cynicism by repeating God's prohibition against eating fruit from the tree of knowledge (Genesis 2:17).[18][19] The woman is lured into dialogue on the serpent's terms which directly disputes God's command.[20] The serpent assures the woman that God will not let her die if she ate the fruit, and, furthermore, that if she ate the fruit, her "eyes would be opened" and she would "be like God, knowing good and evil" (Genesis 3:5).[21] The woman sees that the fruit of the tree of knowledge is a delight to the eye and that it would be desirable to acquire wisdom by eating the fruit. The woman eats the fruit and gives some to the man (Genesis 3:6).[22] With this the man and woman recognize their own nakedness, and they make loincloths of fig leaves (Genesis 3:7).[23][24]

In the next narrative dialogue, God questions the man and the woman (Genesis 3:8–13),[25][15] and God initiates a dialogue by calling out to the man with a rhetorical question designed to consider his wrongdoing. The man explains that he hid in the garden out of fear because he realized his own nakedness (Genesis 3:10).[26][27] This is followed by two more rhetorical questions designed to show awareness of a defiance of God's command. The man then points to the woman as the real offender, and he implies that God is responsible for the tragedy because the woman was given to him by God (Genesis 3:12).[28][29] God challenges the woman to explain herself, and she shifts the blame to the serpent (Genesis 3:13).[30][31]

Divine pronouncement of three judgments is then laid against all the culprits (Genesis 3:14–19).[32][15] A judgement oracle and the nature of the crime is first laid upon the serpent, then the woman, and, finally, the man. On the serpent, God places a divine curse.[33] The woman receives penalties that impact her in two primary roles: she shall experience pangs during childbearing, pain during childbirth, and while she shall desire her husband, he will rule over her.[34] The man's penalty results in God cursing the ground from which he came, and the man then receives a death oracle, although the man has not been described, in the text, as immortal.[17]: 18 [35] Abruptly, in the flow of text, in Genesis 3:20,[36] the man names the woman "Eve" (Hebrew hawwah), "because she was the mother of all living". God makes skin garments for Adam and Eve (Genesis 3:20).[37]

The chiasmus structure of the death oracle given to Adam in Genesis 3:19[38] is a link between man's creation from "dust" (Genesis 2:7)[39] to the "return" of his beginnings:[40] "you return, to the ground, since from it you were taken, for dust you are, and to dust, you will return."

The garden account ends with an intradivine monologue, determining the couple's expulsion, and the execution of that deliberation (Genesis 3:22–24).[41][15] The reason given for the expulsion was to prevent the man from eating from the tree of life and becoming immortal: "Behold, the man is become as one of us, to know good and evil; and now, lest he put forth his hand, and take also of the tree of life, and eat, and live for ever" (Genesis 3:22).[42][17]: 18 [43] God exiles Adam and Eve from the Garden and installs cherubs (supernatural beings that provide protection) and the "ever-turning sword" to guard the entrance (Genesis 3:24).[44][45]

Offspring

Genesis 4 narrates life outside the garden, including the birth of Adam and Eve's first children Cain and Abel and the story of the first murder. A third son, Seth, is born to Adam and Eve, and Adam had "other sons and daughters" (Genesis 5:4).[46] Genesis 5 lists Adam's descendants from Seth to Noah with their ages at the birth of their first sons and their ages at death. Adam's age at death is given as 930 years. According to the Book of Jubilees, Cain married his sister Awan, a daughter of Adam and Eve.[47] According to the Pseudo-Philo, Adam and Eve's male children were: Eliseel, Suris, Elamiel, Brabal, Naat, Zarama, Zasam, Maathal, and Anath. And Adam and Eve's female children were: Phua, Iectas, Arebica, Sifa, Tecia, Saba, and Asin.[48]

Textual history

The Primeval History forms the opening chapters of the Torah, the five books making up the history of the origins of Israel. This achieved something like its current form in the 5th century BCE,[49] but Genesis 1–11 shows little relationship to the rest of the Bible:[50] for example, the names of its characters and its geography – Adam (man) and Eve (life), the Land of Nod ("Wandering"), and so on – are symbolic rather than real,[51] and almost none of the persons, places and stories mentioned in it are ever met anywhere else.[51] This has led scholars to suppose that the History forms a late composition attached to Genesis and the Pentateuch to serve as an introduction.[52] Just how late is a subject for debate: at one extreme are those who see it as a product of the Hellenistic period, in which case it cannot be earlier than the first decades of the 4th century BCE;[53] on the other hand the Yahwist source has been dated by some scholars, notably John Van Seters, to the exilic pre-Persian period (the 6th century BCE) precisely because the Primeval History contains so much Babylonian influence in the form of myth.[54][Note 2] The Primeval History draws on two distinct "sources", the Priestly source and what is sometimes called the Yahwist source and sometimes simply the "non-Priestly"; for the purpose of discussing Adam and Eve in the Book of Genesis the terms "non-Priestly" and "Yahwist" can be regarded as interchangeable.[55]

Abrahamic traditions

Judaism

It was also recognized in ancient Judaism that there are two distinct accounts for the creation of man. The first account says "male and female [God] created them", implying simultaneous creation, whereas the second account states that God created Eve subsequent to the creation of Adam. The Midrash Rabbah – Genesis VIII:1 reconciled the two by stating that Genesis one, "male and female He created them", indicates that God originally created Adam as a hermaphrodite,[56] bodily and spiritually both male and female, before creating the separate beings of Adam and Eve. Other rabbis suggested that Eve and the woman of the first account were two separate individuals, the first being identified as Lilith, a figure elsewhere described as a night demon.

According to traditional Jewish belief, Adam and Eve are buried in the Cave of Machpelah, in Hebron.

In Genesis 2:7 "God breathes into the man's nostrils and he becomes nefesh hayya", signifying something like the English word "being", in the sense of a corporeal body capable of life; the concept of a "soul" in the modern sense, did not exist in Hebrew thought until around the 2nd century BC, when the idea of a bodily resurrection gained popularity.[57]

Christianity

Some early fathers of the Christian church held Eve responsible for the Fall of man and all subsequent women to be the first sinners because Eve tempted Adam to commit the taboo. "You are the devil's gateway" Tertullian told his female readers, and went on to explain that they were responsible for the death of Christ: "On account of your desert [i.e., punishment for sin, that is, death], even the Son of God had to die."[58] In 1486, the Dominicans Kramer and Sprengler used similar tracts in Malleus Maleficarum ("Hammer of Witches") to justify the persecution of "witches".

Medieval Christian art often depicted the Edenic Serpent as a woman (often identified as Lilith), thus both emphasizing the serpent's seductiveness as well as its relationship to Eve. Several early Church Fathers, including Clement of Alexandria and Eusebius of Caesarea, interpreted the Hebrew "Heva" as not only the name of Eve, but in its aspirated form as "female serpent."

Based on the Christian doctrine of the Fall of man, came the doctrine of original sin. St Augustine of Hippo (354–430), working with the Epistle to the Romans, interpreted the Apostle Paul as having said that Adam's sin was hereditary: "Death passed upon [i.e., spread to] all men because of Adam, [in whom] all sinned", Romans 5:12[59] Original sin became a concept that man is born into a condition of sinfulness and must await redemption. This doctrine became a cornerstone of the Western Christian theological tradition, which however not shared by Judaism or the Orthodox churches.

Over the centuries, a system of unique Christian beliefs had developed from these doctrines. Baptism became understood as a washing away of the stain of hereditary sin in many churches, although its original symbolism was apparently rebirth. Additionally, the serpent that tempted Eve was interpreted to have been Satan, or that Satan was using a serpent as a mouthpiece, although there is no mention of this identification in the Torah and it is not held in Judaism.

As well as developing the theology of the protoplasts, the medieval Church also expanded the historical narrative in a vast tradition of Adam books, which add detail to the fall, and tell of their life after the expulsion from Eden. These are continued in the Legend of the Rood, dealing with Seth's return to Paradise and subsequent events involving the wood from the tree of life. These stories were widely believed in Europe until early modern times.

Regarding the real existence of the progenitors – as of other narratives contained in Genesis – the Catholic Church teaches that Adam and Eve were historical humans, personally responsible for the original sin. This position was clarified by Pope Pius XII in the encyclical Humani Generis, in which the Pope condemned the theory of polygenism and expressed that original sin comes "from a sin actually committed by an individual Adam". Despite this, the Humani Generis also states that the belief in evolution is not in contrast to Catholic doctrine; this has led to a gradual acceptance of theistic evolution among Roman Catholic and Independent Catholic theologians, a position that has been encouraged by Pope John Paul II, Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis.[60][61][62][63]

The biblical fall of Adam and Eve is also understood by some Christians (especially those in the Eastern Orthodox tradition) as a reality outside of empirical history that effects the entire history of the universe. This concept of an atemporal fall has been most recently expounded by the Orthodox theologians David Bentley Hart, John Behr, and Sergei Bulgakov, but it has roots in the writings of several early church fathers, especially Origen and Maximus the Confessor.[64][65][66] Bulgakov writes in his 1939 book The Bride of the Lamb translated by Boris Jakim (Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2001) that "empirical history begins precisely with the fall, which is its starting premise" and that in the "narrative in Genesis 3, ...an event is described that lies beyond our history, although at its boundary."[67] David Bentley Hart has written about this concept of an atemporal fall in his 2005 book The Doors of the Sea as well as in his essay "The Devil's March: Creatio ex Nihilo, the Problem of Evil, and a Few Dostoyevskian Meditations" (from his 2020 book Theological Territories).[68]

Gnostic traditions

Gnostics discussed Adam and Eve in two known surviving texts, namely the "Apocalypse of Adam" found in the Nag Hammadi documents and the Testament of Adam. The creation of Adam as Protoanthropos, the original man, is the focal concept of these writings.

Another Gnostic tradition held that Adam and Eve were created to help defeat Satan. The serpent, instead of being identified with Satan, is seen as a hero by the Ophites. Still other Gnostics believed that Satan's fall, however, came after the creation of humanity. As in Islamic tradition, this story says that Satan refused to bow to Adam due to pride. Satan said that Adam was inferior to him as he was made of fire, whereas Adam was made of clay. This refusal led to the fall of Satan recorded in works such as the Book of Enoch.

In Mandaeism, "(God) created all the worlds, formed the soul through his power, and placed it by means of angels into the human body. So He created Adam and Eve, the first man and woman."[69]

Islam

In Islam, Adam (Ādam; Arabic: آدم), whose role is being the father of humanity, is looked upon by Muslims with reverence. Eve (Ḥawwāʼ; Arabic: حواء ) is the "mother of humanity".[70] The creation of Adam and Eve is referred to in the Qurʼān, although different Qurʼanic interpreters give different views on the actual creation story (Qurʼan, Surat al-Nisaʼ, verse 1).[71]

In al-Qummi's tafsir on the Garden of Eden, such a place was not entirely earthly. According to the Qurʼān, both Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit in a Heavenly Eden. As a result, they were both sent down to Earth as God's representatives. Each person was sent to a mountain peak: Adam on al-Safa, and Eve on al-Marwah. In this Islamic tradition, Adam wept for 40 days until he repented, after which God sent down the Black Stone, teaching him the Hajj. According to a prophetic hadith, Adam and Eve reunited in the plain of ʻArafat, near Mecca.[72] They had multiple children, particularly, Qabil and Habil.[73] There is also a legend of a younger son, named Rocail, who created a palace and sepulchre containing autonomous statues that lived out the lives of men so realistically they were mistaken for having souls.[74]

The concept of "original sin" does not exist in Islam because, according to Islam, Adam and Eve were forgiven by God. When God orders the angels to bow to Adam, Iblīs questioned, "Why should I bow to man? I am made of pure fire and he is made of soil."[75] The liberal movements within Islam have viewed God's commanding the angels to bow before Adam as an exaltation of humanity, and as a means of supporting human rights; others view it as an act of showing Adam that the biggest enemy of humans on earth will be their ego.[76]

In Swahili literature, Eve ate from the forbidden tree, thus causing her expulsion, after being tempted by Iblis. Thereupon, Adam heroically eats the forbidden fruit in order to follow Eve and protect her on earth.[77]

Baháʼí Faith

In the Baháʼí Faith, Adam is regarded as the first Manifestation of God.[78] The Adam and Eve narrative is seen as symbolic. In Some Answered Questions, 'Abdu'l-Bahá rejects a literal reading and states that the story contains "divine mysteries and universal meanings".[79] Adam symbolizes the "spirit of Adam", Eve symbolizes "His self", the Tree of Knowledge symbolizes "the material world", and the serpent symbolizes "attachment to the material world".[80][81][82] The fall of Adam thus represents the way humanity became conscious of good and evil.[78] In another sense, Adam and Eve represent God's Will and Determination, the first two of the seven stages of Divine Creative Action.[83]

Historicity

While a traditional view attributes the Book of Genesis to Mosaic authorship, modern scholars consider the Genesis creation narrative as one of various ancient origin myths.[84][85]

Analysis like the documentary hypothesis also suggests that the text is a result of the compilation of multiple previous traditions, explaining apparent contradictions.[86][87] Other stories of the same canonical book, like the Genesis flood narrative, are also understood as having been influenced by older literature, with parallels in the older Epic of Gilgamesh.[88]

Y chromosomal Adam and Mitochondrial Eve

Scientific developments within the natural sciences have shown evidence that humans, and all other living and extinct species, share a common ancestor and evolved through natural processes, over billions of years to diversify into the life forms we know today.[89][90][relevant?]

In biology, the most recent common ancestors of humans, when traced back using the Y chromosome for the male lineage and mitochondrial DNA for the female lineage, are commonly called the Y-chromosomal Adam and Mitochondrial Eve, respectively. Anatomically modern humans emerged in Africa approximately 300,000 years ago.[91] The matrilineal most recent common ancestor lived around 155,000 years ago,[92][93][94][95] while the patrilineal most recent common ancestor lived around 200,000 to 300,000 years ago.[96] These do not fork from a single couple at the same epoch even though the names were borrowed from the Tanakh.[97]

Arts and literature

John Milton's Paradise Lost, a famous 17th-century epic poem written in blank verse, explores and elaborates upon the story of Adam and Eve in great detail. As opposed to the biblical Adam, Milton's Adam is given a glimpse of the future of mankind, by the archangel Michael, before he has to leave Paradise.

Mark Twain wrote humorous and satirical diaries for Adam and Eve in both "Eve's Diary" (1906) and The Private Life of Adam and Eve (1931), posthumously published.

C. L. Moore's 1940 story Fruit of Knowledge is a re-telling of the Fall of Man as a love triangle between Lilith, Adam and Eve – with Eve's eating the forbidden fruit being in this version the result of misguided manipulations by the jealous Lilith, who had hoped to get her rival discredited and destroyed by God and thus regain Adam's love.

In Stephen Schwartz's 1991 musical Children of Eden, "Father" (God) creates Adam and Eve at the same time and considers them his children. They even assist Him in naming the animals. When Eve is tempted by the serpent and eats the forbidden fruit, Father makes Adam choose between Him and Eden, or Eve. Adam chooses Eve and eats the fruit, causing Father to banish them into the wilderness and destroying the Tree of Knowledge, from which Adam carves a staff. Eve gives birth to Cain and Abel, and Adam forbids his children from going beyond the waterfall in hopes Father will forgive them and bring them back to Eden. When Cain and Abel grow up, Cain breaks his promise and goes beyond the waterfall, finding the giant stones made by other humans, which he brings the family to see, and Adam reveals his discovery from the past: during their infancy, he discovered these humans, but had kept it secret. He tries to forbid Cain from seeking them out, which causes Cain to become enraged and he tries to attack Adam, but instead turns his rage to Abel when he tries to stop him and kills him. Later, when an elderly Eve tries to speak to Father, she tells how Adam continually looked for Cain, and after many years, he dies and is buried underneath the waterfall. Eve also gave birth to Seth, which expanded hers and Adam's generations. Finally, Father speaks to her to bring her home. Before she dies, she gives her blessings to all her future generations, and passes Adam's staff to Seth. Father embraces Eve and she also reunited with Adam and Abel. Smaller casts usually have the actors cast as Adam and Eve double as Noah and Mama Noah.

In Ray Nelson's novel Blake's Progress the poet William Blake and his wife Kate travel to the end of time where the demonic Urizen offers them his own re-interpretation of the Biblical story: "In this painting you see Adam and Eve listening to the wisdom of their good friend and adviser, the serpent. One might even say he was their Savior. He gave them freedom, and he would have given them eternal life if he'd been allowed to."[citation needed]

John William "Uncle Jack" Dey painted Adam and Eve Leave Eden (1973), using stripes and dabs of pure color to evoke Eden's lush surroundings.[98]

In C.S. Lewis' 1943 science fiction novel Perelandra, the story of Adam and Eve is re-enacted on the planet Venus – but with a different ending. A green-skinned pair, who are destined to be the ancestors of Venusian humanity, are living in naked innocence on wonderful floating islands which are the Venusian Eden; a demonically possessed Earth scientist arrives in a spaceship, acting the part of the snake and trying to tempt the Venusian Eve into disobeying God; but the protagonist, Cambridge scholar Ransom, succeeds in thwarting him, so that Venusian humanity will have a glorious future, free of original sin.

Image gallery

-

Early Christian depiction of Adam and Eve in the Catacombs of Marcellinus and Peter

-

Detail of a stained glass window (12th century) in Saint-Julien cathedral - Le Mans, France

-

Depiction of the Fall in Kunsthalle Hamburg, by Master Bertram, 1375-1383

-

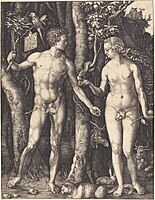

Adam and Eve, engraving by Albrecht Dürer, 1504 (National Gallery of Art)

-

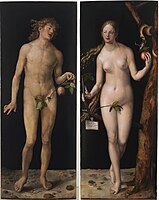

Adam and Eve by Albrecht Dürer, 1507

-

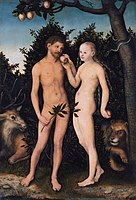

Adam and Eve in paradise (The Fall), Eve gives Adam the forbidden fruit, by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1533

-

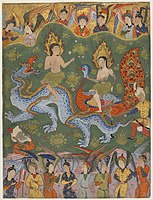

Adam and Eve from a copy of the Falnama (Book of Omens) ascribed to Ja'far al-Sadiq, c. 1550, Safavid dynasty, Iran

-

Adam and Eve by Titian, c. 1550

-

Adam and Eve by Maarten van Heemskerck, 1550

-

Adam and Eve Driven From Paradise by James Tissot, c. 1896-1902

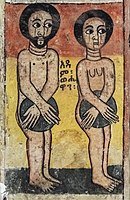

-

Adam and Eve depicted in a mural in Abreha wa Atsbeha Church, Ethiopia

-

1896 illustration of Eve handing Adam the forbidden fruit

-

Adam and Eve by Frank Eugene, taken 1898, published in Camera Work no. 30, 1910

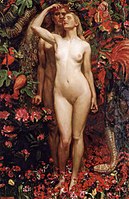

-

The Woman, the Man, and the Serpent by Byam Shaw, 1911

-

Adam and Eve by Franz Stuck, 1920

See also

Notes

- ^ Myth in this case not meaning a false story, but rather a traditional story which embodies a belief regarding some fact or phenomenon of experience, and in which often the forces of nature and of the soul are personified; a sacred narrative regarding a god, a hero, the origin of the world or of a people, etc.

- ^ See John Van Seters, Prologue to History: The Yahwist as Historian in Genesis Archived 2022-11-02 at the Wayback Machine (1992), pp.80, 155–156.

References

- ^ Womack, Mari (2005). Symbols and Meaning: A Concise Introduction. Walnut Creek ... [et al.]: Altamira Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0759103221. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

Creation myths are symbolic stories describing how the universe and its inhabitants came to be. Creation myths develop through oral traditions and therefore typically have multiple versions.

- ^ Leeming, David (2010). Creation Myths of the World: Parts I-II. p. 303.

- ^ Azra, Azyumardi (2009). "Chapter 14. Trialogue of Abrahamic Faiths: Towards an Alliance of Civilizations". In Ma'oz, Moshe (ed.). The Meeting of Civilizations: Muslim, Christian, and Jewish. Eastbourne: Sussex Academic Press. pp. 220–229. ISBN 978-1-845-19395-9.

- ^ Alfred J., Kolatch (1985). The Second Jewish Book of Why (2nd, revised ed.). New York City: Jonathan David Publishers. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-824-60305-2. Excerpt in Judaism's Rejection Of Original Sin Archived 2016-12-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Enns 2012, p. 84.

- ^ Blenkinsopp 2011, p. 3.

- ^ Blenkinsopp 2011, p. ix.

- ^ Blenkinsopp 2011, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Hearne 1990, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f Galambush 2000, p. 436.

- ^ Kramer 1963, p. 149.

- ^ Collon, Dominique (1995). Ancient Near Eastern Art. University of California Press. p. 213. ISBN 9780520203075. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

the strange story of Adam's 'spare rib' from which Eve was created (Genesis 2:20–3) makes perfect sense once it is realised that in Sumerian the feminine particle and the words for rib and life are all ti, so that the tale in its original form must have been based on Sumerian puns.

- ^ Alter 2004, p. 27–28.

- ^ Freedman, Meyers, Patrick (1983). Carol L. Meyers; Michael Patrick O'Connor; David Noel Freedman (eds.). The Word of the Lord Shall Go Forth: Essays in Honor of David Noel Freedman. Eisenbrauns. pp. 343–344. ISBN 9780931464195.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Mathews 1996, p. 226

- ^ Genesis 3:1

- ^ a b c Levenson, Jon D. (2004). "Genesis: Introduction and Annotations". In Berlin, Adele; Brettler, Marc Zvi (eds.). The Jewish Study Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195297515.

- ^ Genesis 2:17

- ^ Mathews 1996, p. 235

- ^ Mathews 1996, p. 236

- ^ Genesis 3:5

- ^ Genesis 3:6

- ^ Genesis 3:7

- ^ Mathews 1996, p. 237

- ^ Genesis 3:8–13

- ^ Genesis 3:10

- ^ Mathews 1996, p. 240

- ^ Genesis 3:12

- ^ Mathews 1996, p. 241

- ^ Genesis 3:13

- ^ Mathews 1996, p. 242

- ^ Genesis 3:14–19

- ^ Mathews 1996, p. 243

- ^ Mathews 1996, p. 248

- ^ Mathews 1996, p. 252

- ^ Genesis 3:20

- ^ Genesis 3:20

- ^ Genesis 3:19

- ^ Genesis 2:7

- ^ Mathews 1996, p. 253

- ^ Genesis 3:22–24

- ^ Genesis 3:22

- ^ Addis, Edward (1893). The Documents of the Hexateuch, Volume 1. Putnam. pp. 4–7.

- ^ Genesis 3:24

- ^ Weinstein, Brian (2010). 54 Torah Talks: From Layperson to Layperson. iUniverse. p. 4. ISBN 9781440192555.

- ^ Genesis 5:4

- ^ Betsy Halpern Amaru (1999), and by the same book, Seth married Abel's sister, Azura. The Empowerment of Women in the Book of Jubilees, p. 17.

- ^ Anonymous, unknown date, Pseudo-Philo, p. 76

- ^ Enns 2012, p. 5.

- ^ Sailhamer 2010, p. 301 and fn.35.

- ^ a b Blenkinsopp 2011, p. 2.

- ^ Sailhamer 2010, p. 301.

- ^ Gmirkin 2006, p. 240-241.

- ^ Gmirkin 2006, p. 6.

- ^ Carr 2000, p. 492.

- ^ Howard Schwartz (September 2004). Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism: The Mythology of Judaism. Oxford University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0195086799. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

The myth of Adam the Hermaphrodite grows out of three biblical verses

- ^ Harry Orlinsky's Notes to the NJPS Torah

- ^ "Tertullian, "De Cultu Feminarum", Book I Chapter I, Modesty in Apparel Becoming to Women in Memory of the Introduction of Sin Through a Woman (in "The Ante-Nicene Fathers")". Tertullian.org. Retrieved 2014-02-17.

- ^ Fox, Robin Lane (2006) [1991]. The Unauthorized Version: Truth and Fiction in the Bible. Penguin Books Limited. pp. 15–27. ISBN 9780141925752.

- ^ "Humani Generis (August 12, 1950) | PIUS XII". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- ^ Owen, Richard (6 March 2009). "Vatican says Evolution does not prove the non existence of God". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460.

- ^ John Paul II, Message to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences: On Evolution Archived 2021-12-08 at the Wayback Machine; the speech was made in French - for a dispute over whether the correct English translation of "la theorie de l'evolution plus qu'une hypothese" is "more than a hypothesis" or "more than one hypothesis", see Eugenie Scott, NCSE online version Archived 2018-10-02 at the Wayback Machine of Creationists and the Pope's Statement, which originally appeared in The Quarterly Review of Biology, 72.4, December 1997

- ^ McKenna, Josephine (2014-10-27). "Pope Francis: 'Evolution ... is not inconsistent with the notion of creation'". Religion News Service.

- ^ Hart, David Bentley (31 August 2022). "Sensus Plenior I: On gods and mortals". Leaves in the Wind. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

First Reader (Aug 31, 2022): Should we favor the 'atemporal fall' view then? David Bentley Hart (Aug 31, 2022): Well, I certainly do. But the original Eden story isn't about the 'fall' at all, except in the vague sense that it was a mythic aetiology of life's miseries. Second Reader (Sep 2, 2022): Can you briefly describe what you understand or hold the 'atemporal fall' to be? Hart (Sep 2, 2022): No, not briefly. Second Reader (Sep 2, 2022): An extended response would, of course, be satisfactory also! But no, if you are aware of any particularly good reflections on it, I'd be grateful for a reference. Hart (Sep 2, 2022): Bulgakov, The Bride of the Lamb

- ^ Behr, John (15 January 2018). "Origen and the Eschatological Creation of the Cosmos". Eclectic Orthodoxy. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

Our beginning in this world and its time can only be thought of as a falling away from that eternal and heavenly reality, to which we are called.

- ^ Chenoweth, Mark (Summer 2022). "The Redemption of Evolution: Maximus the Confessor, The Incarnation, and Modern Science". Jacob's Well. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Bulgakov, Sergei (2001). "Evil". The Bride of the Lamb. Translated by Jakim, Boris. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans. p. 170. ISBN 9780802839152.

- ^ Hart, David Bentley (2020). "The Devil's March: Creatio ex Nihilo, the Problem of Evil, and a Few Dostoyevskian Meditations". Theological Territories: A David Bentley Hart Digest. Notre Dame, Indiana: Notre Dame Press. ISBN 9780268107178.

- ^ Al-Saadi, Qais (27 September 2014), "Ginza Rabba "The Great Treasure" The Holy Book of the Mandaeans in English", Mandaean Associations Union, retrieved 28 November 2021

- ^ Historical Dictionary of Prophets in Islam and Judaism, Wheeler, "Adam and Eve"

- ^ Quran 4:1:O mankind! Be dutiful to your Lord, Who created you from a single person (Adam), and from him (Adam) He created his wife Hawwa (Eve), and from them both He created many men and women;

- ^ Wheeler, Brannon (July 2006). Mecca and Eden: Ritual, Relics, and Territory in Islam – Brannon M. Wheeler – Google Books. University of Chicago Press. p. 85. ISBN 9780226888040. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ^ al-Tabari (1989). The History of al-Tabari. New York: State University of New York Press. p. 259. ISBN 0-88706-562-7.

- ^ Godwin, William (1876). Lives of the Necromancers. Chatto and Windus. pp. 112–113. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ Quran 7:12

- ^ Javed Ahmed Ghamidi, Mizan. Lahore: Dar al-Ishraq, 2001

- ^ John Renard Islam and the Heroic Image: Themes in Literature and the Visual Arts Mercer University Press 1999 ISBN 9780865546400 p. 122

- ^ a b Smith, Peter (2000). "Adam". A Concise Encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith. London: Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1-78074-480-3. OCLC 890982216. Retrieved 2021-06-26 – via Google Books.

- ^ Sours, Michael (2001). The Tablet of the Holy Mariner: An Illustrated Guide to Baha'u'llah's Mystical Work in the Sufi Tradition. Los Angeles: Kalimát Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-890688-19-6.

- ^ ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (2014) [1908]. Some Answered Questions (newly revised. ed.). Haifa, Israel: Baháʼí World Centre. ISBN 978-0-87743-374-3.

- ^ Momen, Wendy (1989). A Basic Baháʼí Dictionary. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-85398-231-9.

- ^ McLean, Jack (1997). Revisioning the Sacred: New Perspectives on a Baháʼí Theology – Volume 8. Archived 2022-11-02 at the Wayback Machine p. 215.

- ^ Saiedi, Nader (2008). Gate of the Heart. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-1-55458-035-4.

- ^ Van Seters, John (1998). "The Pentateuch". In Steven L. McKenzie, Matt Patrick Graham (ed.). The Hebrew Bible Today: An Introduction to Critical Issues. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780664256524.

- ^ Davies, G.I (1998). "Introduction to the Pentateuch". In John Barton (ed.). Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. p. 37. ISBN 9780198755005.

- ^ Gooder, Paula (2000). The Pentateuch: A Story of Beginnings. T&T Clark. pp. 12–14. ISBN 9780567084187.

- ^ Van Seters, John (2004). The Pentateuch: A Social-science Commentary. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 30–86. ISBN 9780567080882.

- ^ Finkel, Irving (2014). The Ark Before Noah. UK: Hachette. p. 88. ISBN 9781444757071.

- ^ Kampourakis, Kostas (2014). Understanding Evolution. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 127–129. ISBN 978-1-107-03491-4. LCCN 2013034917. OCLC 855585457.

- ^ Schopf, J. William; Kudryavtsev, Anatoliy B.; Czaja, Andrew D.; Tripathi, Abhishek B. (October 5, 2007). "Evidence of Archean life: Stromatolites and microfossils". Precambrian Research. 158 (3–4): 141–155. Bibcode:2007PreR..158..141S. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2007.04.009. ISSN 0301-9268.

- ^ Schlebusch; et al. (3 November 2017). "Southern African ancient genomes estimate modern human divergence to 350,000 to 260,000 years ago". Science. 358 (6363): 652–655. Bibcode:2017Sci...358..652S. doi:10.1126/science.aao6266. PMID 28971970.

- ^ Soares P, Ermini L, Thomson N, Mormina M, Rito T, Röhl A, et al. (June 2009). "Correcting for purifying selection: an improved human mitochondrial molecular clock". American Journal of Human Genetics. 84 (6): 740–759

- ^ Poznik GD, Henn BM, Yee MC, Sliwerska E, Euskirchen GM, Lin AA, et al. (August 2013). "Sequencing Y chromosomes resolves discrepancy in time to common ancestor of males versus females". Science. 341 (6145): 562–565.

- ^ Fu Q, Mittnik A, Johnson PL, Bos K, Lari M, Bollongino R, et al. (April 2013). "A revised timescale for human evolution based on ancient mitochondrial genomes". Current Biology. 23 (7): 553–559.

- ^ Explanation of the three studies cited: Two studies published in 2013 had 95% confidence intervals barely overlapping in the neighbourhood of 15 ka, a third study had a 95% confidence interval intermediate between the two others: "99 to 148 ka" according to Poznik, 2013 (ML whole-mtDNA age estimate: 178.8 [155.6; 202.2], ρ whole-mtDNA age estimate: 185.2 [153.8; 216.9], ρ synonymous age estimate: 174.8 [153.8; 216.9]), "134 to 188 ka", according to Fu, 2013, and 150 to 234 ka (95% CI) from Soares, 2009.

- ^ Karmin; et al. (2015). "A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture". Genome Research. 25 (4): 459–66. doi:10.1101/gr.186684.114. PMC 4381518. PMID 25770088.

we date the Y-chromosomal most recent common ancestor (MRCA) in Africa at 254 (95% CI 192–307) kya and detect a cluster of major non-African founder haplogroups in a narrow time interval at 47–52 kya, consistent with a rapid initial colonization model of Eurasia and Oceania after the out-of-Africa bottleneck. In contrast to demographic reconstructions based on mtDNA, we infer a second strong bottleneck in Y-chromosome lineages dating to the last 10 ky. We hypothesize that this bottleneck is caused by cultural changes affecting variance of reproductive success among males.

- ^ Takahata, N (January 1993). "Allelic genealogy and human evolution". Mol. Biol. Evol. 10 (1): 2–22. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a039995. PMID 8450756.

- ^ "Adam and Eve Leave Eden". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

Bibliography

- Almond, Philip C. Adam and Eve in Seventeenth-Century Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999, 2008)

- Alter, Robert (2004). The Five Books of Moses. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-33393-0.

- Ayoub, Mahmoud. The Qur'an and its Interpreters, SUNY: Albany, 1984

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2011). Creation, Un-creation, Re-creation: A Discursive Commentary on Genesis 1–11. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-567-37287-1.

- Carr, David M. (2000). "Genesis, Book of". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Enns, Peter (2012). The Evolution of Adam: What the Bible Does and Doesn't Say about Human Origins. Baker Books. ISBN 978-1-58743-315-3.

- Galambush, Julie (2000). "Eve". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Gmirkin, Russell (15 May 2006). Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus: Hellenistic Histories and the Date of the Pentateuch. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-567-13439-4.

- Greenblatt, Stephen (2017). The Rise and Fall of Adam and Eve. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-24080-1.

- Hearne, Stephen Z. (1990). "Adam". In Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey (eds.). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865543737.

- Hendel, Ronald S (2000). "Adam". In David Noel Freedman (ed.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Kissling, Paul (2004). Genesis, Volume 1. College Press. ISBN 978-0899008752.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-45238-7.

- Mathews, K. A. (1996). Genesis 1–11:26. B&H Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0805401011.

- Mckenzie, John L. (1995). The Dictionary of the Bible. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780684819136.

- Murdoch, Brian O. The Apocryphal Adam and Eve in Medieval Europe: Vernacular Translations and Adaptations of the Vita Adae et Evae. Oxford University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-19-956414-9

- Patai, R. The Jewish Alchemists, Princeton University Press, 1994.

- Rana & Hugh. Fazale Rana and Ross, Hugh, Who Was Adam: A Creation Model Approach to the Origin of Man, 2005, ISBN 1-57683-577-4

- Sailhamer, John H. (21 December 2010). Introduction to Old Testament Theology: A Canonical Approach. Zondervan Academic. ISBN 978-0-310-87721-9.

- Sykes, Bryan. The Seven Daughters of Eve

External links

- First Human Beings (Library of Congress)

- The Story of Lilith in The Alphabet of Ben Sira

- Islamic view of the fall of Adam (audio)

- 98 classical images of Adam and Eve Archived 2019-01-03 at the Wayback Machine

- The Book of Jubilees

- Adam and Eve in Medieval Reliefs, Capitals, Frescoes, Roof Bosses and Mosaics Cynistory and Phantamangas of Finceland

- "Adam and Eve" at the Christian Iconography website

- Translation of Grimm's Fairy Tale No. 180, Eve's Unequal Children, a German Fairy Tale about Adam and Eve

- Jewish Encyclopedia