Abiy Ahmed

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Excessive quotes from sources in citations. (March 2024) |

Abiy Ahmed | |

|---|---|

አብይ አሕመድ | |

Abiy in 2018 | |

| Prime Minister of Ethiopia | |

| Assumed office 2 April 2018 | |

| President | |

| Deputy | |

| Preceded by | Hailemariam Desalegn |

| 1st President of the Prosperity Party | |

| Assumed office 1 December 2019 | |

| Deputy | |

| Preceded by | Party established |

| 3rd Chairman of the Ethiopian Peoples' Revolutionary Democratic Front | |

| In office 27 March 2018 – 1 December 2019 | |

| Deputy | Demeke Mekonnen |

| Preceded by | Hailemariam Desalegn |

| Succeeded by | Party abolished |

| Leader of the Oromo Democratic Party | |

| In office 22 February 2018 – 1 December 2019 | |

| Deputy | Lemma Megersa |

| Preceded by | Lemma Megersa |

| Succeeded by | Post abolished |

| Minister of Science and Technology | |

| In office 6 October 2015 – 1 November 2016 | |

| Prime Minister | Hailemariam Desalegn |

| Preceded by | Demitu Hambisa |

| Succeeded by | Getahun Mekuria |

| Director General of the Information Network Security Agency | |

Acting | |

| In office 2008–2015 | |

| Preceded by | Teklebirhan Woldearegay |

| Succeeded by | Temesgen Tiruneh |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Abiy Ahmed Ali 15 August 1976 Beshasha, Kaffa Province, Ethiopia |

| Political party | Prosperity Party |

| Other political affiliations | |

| Spouse | Zinash Tayachew |

| Children | 4 |

| Education | Microlink Information Technology College (BA) University of Greenwich (MA) Leadstar College of Management (MBA) Addis Ababa University (PhD) |

| Awards | Nobel Peace Prize (2019) |

| Website | pmo |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Ethiopia |

| Branch/service | Ethiopian Army |

| Years of service | 1991–2010 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | Army Signals Corps |

| Commands | Information Network Security Agency |

| Battles/wars | |

Abiy Ahmed Ali (Oromo: Abiyi Ahmed Alii; Amharic: ዐብይ አሕመድ ዐሊ; born 15 August 1976) is an Ethiopian politician who is the current Prime Minister of Ethiopia since 2018 and the leader of the Prosperity Party since 2019.[1][2] He was awarded the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize "for his efforts to achieve peace and international cooperation, and in particular for his decisive initiative to resolve the border conflict with neighbouring Eritrea".[3] Abiy served as the third chairman of the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) that governed Ethiopia for 28 years and the first person of Oromo descent to hold that position.[4][5] Abiy is a member of the Ethiopian parliament, and was a member of the Oromo Democratic Party (ODP), one of the then four coalition parties of the EPRDF, until its rule ceased in 2019 and he formed his own party, the Prosperity Party.[6][7]

In June 2020, Abiy and the National Election Board of Ethiopia (NEBE) postponed parliamentary elections because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The postponement was criticised, especially from the opposition,[8][9] and raised questions about the delay's constitutional legitimacy.[10] An election was eventually held in 2021. The African Union described the election as an improvement compared to the 2015 election and positive overall, urging the government to continue the commitment to democracy.[11]

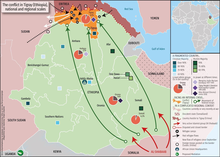

During 2020, ethnic and political tensions grew, and in early November, attacks on the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) Northern Command resulted in the 2-year Tigray War between the combined forces of the ENDF and the Eritrean army against forces loyal to the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF)[12]—as well as those loyal to significant allied groups such as the Oromo Liberation Army.

Since 2019, Ethiopia has undergone democratic backsliding under Abiy's premiership,[13][14] marked by severe human rights violations, media censorship, internet shutdown, civil conflicts and systematic persecution of thousands of ethnic Amharas, and ethnic violence in southern regions of Ethiopia, such as Amaro Koore, Konso and Gedeo Zones.[15][16] Politically motivated purges also became common and many journalists and activists were arrested, by police for alleged breach of "constitutional laws".[17][18] As of June 2022, 18 journalists were arrested in allegation of "inciting violence" while reporting for independent media outlets or YouTube channels.[19] Abiy also believed to lead and organize Koree Nageenyaa, a secret service that purportedly commits unlawful detentions and extrajudicial killings in the Oromia Region with the aim of suppressing uprisings.[20][21][22]

Personal life

Early life

Abiy Ahmed was born in the small town of Beshasha, Ethiopia.[23][24][25][26] His deceased father, Ahmed Ali, was a Muslim Oromo.[27] Abiy's father was a typical Oromo farmer, speaking only Oromo.[28]

The ethnicity of Abiy's deceased mother, Tezeta Wolde, varies according to the sources. The New York Times, in a 2018 interview with Abiy, stated that his mother "was Amhara and Orthodox Christian" and "converted to Islam when she married"[27] and The Guardian in 2019 described Tezeta as Amhara.[29] The Ethiopian Reporter stated in 2019 that Tezeta was "a converted Christian".[30] In a 2021 Oromia Broadcasting Network interview redistributed on YouTube, Abiy stated that his parents were both Oromo, and asserted that "no one is giving or taking away my Oromummaa."[28] Tezeta was a fluent speaker of both Amharic and Oromo.[28]

Abiy is the 13th child of his father and the sixth and youngest child of his mother, the fourth of his father's four wives.[23] His childhood name was Abiyot (English: "Revolution"). The name was sometimes given to children in the aftermath of the Ethiopian Revolution in the mid-1970s.[23] The then Abiyot went to the local primary school and later continued his studies at secondary schools in Agaro town. Abiy, according to several personal reports, was always very interested in his own education and later in his life also encouraged others to learn and to improve.[23] Abiy married Zinash Tayachew, an Amhara woman from Gondar,[23][31] while both were serving in the Ethiopian National Defense Force.[32] They are the parents of three daughters and one adopted son.[32] Abiy speaks Oromo, Amharic, Tigrinya and English.[33] He is a fitness aficionado and frequents physical and gym activities in Addis Ababa.[32]

Religion

Abiy is a Pentecostal Christian,[34][35] born of a Muslim father and a Christian mother. He was raised in a family of religious plurality. Abiy and his family are regular church attendees, and he also occasionally ministers in preaching and teaching the Gospel at the Ethiopian Full Gospel Believers' Church. His wife Zinash Tayachew is also a Christian who ministers in her church as a gospel singer.

Education

While serving in the Ethiopian National Defense Force, Abiy received his first degree, a Bachelor's degree in computer engineering[36] from the Microlink Information Technology College in Addis Ababa in 2009.[37]

Abiy holds a Master of Arts in transformational leadership[36] earned from the business school at Greenwich University, London, in collaboration with the International Leadership Institute, Addis Ababa, in 2011. He also holds a Master of Business Administration from the Leadstar College of Management and Leadership in Addis Ababa in partnership with Ashland University[38][39] in 2013.[40]

Abiy, who had started his Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) work as a regular student,[41] submitted his PhD thesis in 2016,[42] and defended it in 2017[43][44][45] at the Institute for Peace and Security Studies, Addis Ababa University. He did his PhD work on the Agaro constituency with the PhD thesis entitled "Social Capital and its Role in Traditional Conflict Resolution in Ethiopia: The Case of Inter-Religious Conflict In Jimma Zone State", supervised by Amr Abdallah[42]). In 2022, Alex de Waal described Abiy's PhD thesis as constituting an anecdote on an event in which an individual friendship between people of opposite sides augmented social capital and inspired the resolution of a local violent conflict in Jimma Zone. De Waal saw the thesis as "perhaps enough for an undergraduate paper", but not deep enough to cover social capital, background literature on armed conflict and resolution, or literature on "identity, nationalism and conflict".[43] In 2023, de Waal and colleagues recommended that Addis Ababa University re-examine Abiy's PhD thesis for plagiarism, based on their claim of the presence of plagiarism on every page of Chapter 2 of the thesis.[46]

Abiy published a related short research article on de-escalation strategies in the Horn of Africa in a special journal issue dedicated to countering violent extremism.[45]

Military career

At the age of 14, in early 1991,[47] he joined the armed struggle against the Marxist–Leninist regime of Mengistu Haile Mariam after the death of his oldest brother. He was a child soldier, affiliated to the Oromo People's Democratic Organization (OPDO), which at that time was a tiny organization of only around 200 fighters part of the large coalition army of the EPRDF which had over 100,000 fighters that resulted in the regime's fall later that year.[33][23][32] As there were only so few OPDO fighters in an army with its core of about 90,000 Tigrayans, Abiy quickly had to learn the Tigrinya language. As a speaker of Tigrinya in a security apparatus dominated by Tigrayans, he could move forward with his military career.[33]

After the fall of the Derg, he took formal military training from Assefa Brigade in West Wollega and was stationed there. Later on in 1993 he became a soldier in the now Ethiopian National Defense Force and worked mostly in the intelligence and communications departments. In 1995, after the Rwandan genocide, he was deployed as a member of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) in the country's capital, Kigali.[48] In the Eritrean–Ethiopian War that occurred between 1998 and 2000, he led an intelligence team to discover positions of the Eritrean Defence Forces.[49]

Later on, Abiy was posted back to his home town of Beshasha, where he – as an officer of the Defense Forces – had to address a critical situation of inter-religious clashes between Muslims and Christians with a number of deaths.[33][50] He brought calm and peace in a situation of communal tensions accompanying the clashes.[33] In later years, following his election as an MP, he continued these efforts to bring about reconciliation between the religions through the creation of the Religious Forum for Peace.[49]

In 2006, Abiy was one of the co-founders of the Ethiopian Information Network Security Agency (INSA), where he worked in different positions.[23] For two years, he was acting director of INSA due to the director's leave of absence.[23] In this capacity, he was board member of several government agencies working on information and communications, like Ethio telecom and Ethiopian Television. He attained the rank of Lieutenant colonel[45][33] before deciding in 2010 to leave the military and his post as deputy director of INSA (Information Network Security Agency) to become a politician.

Political career

Member of Parliament

Abiy started his political career as a member of the Oromo Democratic Party (ODP).[51] The ODP has been the ruling party in Oromia Region since 1991 and also one of four coalition parties of the ruling coalition in Ethiopia, the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). He became a member of the central committee of ODP and congress member of the executive committee of the EPRDF in quick succession.[33] In the 2010 national election, Abiy represented the district of Agaro and became an elected member of the House of Peoples' Representatives, the lower chamber of the Ethiopian Federal Parliamentary Assembly. Before and during his time of parliamentary service, there were several religious clashes among Muslims and Christians in Jimma Zone. Some of these confrontations turned violent and resulted in the loss of life and property. Abiy, as an elected member of parliament took a proactive role in working with several religious institutions and elders to bring about reconciliation in the zone. He helped set up a forum entitled "Religious Forum for Peace", an outcome of the need to devise a sustainable resolution mechanism to restore peaceful Muslim-Christian community interaction in the region.[45]

In 2014, during his time in parliament, Abiy became the director-general of a new and in 2011 founded Government Research Institute called Science and Technology Information Center (STIC).[23][52] The following year, Abiy became an executive member of ODP. The same year he was elected to the House of Peoples' Representatives for a second term, this time for his home woreda of Gomma.[53]

Rise to power

Starting from 2015, Abiy became one of the central figures in the violent fight against illegal land grabbing activities in Oromia Region and especially around Addis Ababa. Although the Addis Ababa Master Plan at the heart of the land-grabbing plans was stopped in 2016, the disputes continued for some time resulting in injuries and deaths.[54] It was this fight against land-grabbing, that finally boosted Abiy Ahmed's political career, brought him into the spotlight and allowed him to climb the political ladder.[33]

In October 2015, Abiy became the Ethiopian Minister of Science and Technology (MoST), a post which he left after only 12 months. From October 2016 on, Abiy served as Deputy President of Oromia Region as part of the team of Oromia Region's president Lemma Megersa while staying a member of the Ethiopian Federal House of Peoples' Representatives.[55][56] Abiy Ahmed also became the head of the Oromia Urban Development and Planning Office. In this role, Abiy was expected to be the major driving force behind Oromia Economic Revolution, Oromia Land and Investment reform, youth employment as well as resistance to widespread land grabbing in Oromia region.[57] As one of his duties in office, he took care of the one million displaced Oromo people displaced from the Somali Region from the 2017 unrest.[58]

As head of the ODP Secretariat from October 2017, Abiy facilitated the formation of a new alliance between the Oromo and Amhara groups, which together constitute two-thirds of the Ethiopian population.[59]

In early 2018, many political observers considered Abiy and Lemma Megersa as the most popular politicians within the Oromo community, as well as other Ethiopian communities.[60][61] This came after several years of unrest in Ethiopia. But despite this favourable rating for Abiy Ahmed and Lemma Megersa, young people from the Oromia region called for immediate action without delays to bring fundamental change and freedom to Oromia Region and Ethiopia – otherwise more unrest was to be expected.[54] According to Abiy himself, people are asking for a different rhetoric, with an open and respectful discussion in the political space to allow political progress and to win people for democracy instead of pushing them.[54]

Until early 2018, Abiy continued to serve as head of the ODP secretariat and of the Oromia Housing and Urban Development Office and as Deputy President of Oromia Region. He left all these posts after his election as the leader of the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front.[62][55]

EPRDF leadership election

Following three years of protest and unrest, on 15 February 2018 the Ethiopian Prime Minister, Hailemariam Desalegn, announced his resignation – which included his resignation from the post of EPRDF chairman. With the EPRDF's large majority in Parliament, its EPRDF chairman was all but assured of becoming the next Prime Minister. The EPRDF chairman, on the other hand, is one of the heads of the four parties that make up the ruling coalition: Oromo Democratic Party (ODP), Amhara Democratic Party (ADP), Southern Ethiopian People's Democratic Movement (SEPDM) and Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF).[63]

Hailemariam's resignation triggered the first ever contested leadership election among EPRDF coalition members to replace him. A lot of political observers made Lemma Megersa (the ODP chairman) and Abiy Ahmed the front-runners to become the Leader of the ruling coalition and eventually Prime Minister of Ethiopia. Despite being the clear favorite for the general public, Lemma Megersa was not a member of the national parliament, a requirement to become Prime Minister as required by the Ethiopian constitution. Therefore, Lemma Megersa was excluded from the leadership race.[64] On 22 February 2018, Lemma Megersa's party, ODP, called for an emergency executive committee meeting and replaced him as Chairman of ODP with Abiy Ahmed, who was a member of parliament. Some observers saw that as a strategic move by the ODP to retain its leadership role within the coalition and to promote Abiy Ahmed to become prime minister.[53]

On 1 March 2018, the 180 EPRDF executive committee members started their meeting to elect the leader of the party. Each of the four parties sent in 45 members. The contest for the leadership was among Abiy Ahmed of ODP, Demeke Mekonnen, the Deputy Prime Minister and ADP leader, Shiferaw Shigute as Chairman of SEPDM and Debretsion Gebremichael as the Leader of TPLF. Despite being the overwhelming favorite by the majority of Ethiopians, Abiy Ahmed faced major opposition from TPLF and SEPDM members during the leadership discussions.[65]

On 27 March 2018, a few hours before the beginning of the leadership elections, Demeke Mekonnen, who had been seen as the major opponent to Abiy Ahmed, dropped out of the race. Many observers saw this as an endorsement of Abiy Ahmed. Demeke was then approved as deputy prime minister for another term. Following Demeke's exit, Abiy Ahmed received a presumably unanimous vote from both the ADP and ODP executive members, with 18 additional votes in a secret ballot coming from elsewhere. By midnight, Abiy Ahmed was declared chairman of the ruling coalition in Ethiopia, the EPRDF, and was considered as the Prime Minister Designate of Ethiopia by receiving 108 votes while Shiferaw Shigute received 58 and Debretsion Gebremichael received 2 votes.[5] On 2 April 2018, Abiy Ahmed was elected as Prime Minister of Ethiopia by the House of Representatives and sworn in.[2]

Prime Minister of Ethiopia

On 2 April 2018, Abiy was confirmed and sworn in by the Ethiopian parliament as Prime Minister of Ethiopia. During his acceptance speech, he promised political reform; to promote the unity of Ethiopia and unity among the peoples of Ethiopia; to reach out to the Eritrean government to resolve the ongoing Eritrean–Ethiopian border conflict after the Eritrean–Ethiopian War and to also reach out to the political opposition inside and outside of Ethiopia. His acceptance speech sparked optimism and received an overwhelmingly positive reaction from the Ethiopian public including the opposition groups inside and outside Ethiopia. Following his speech, his popularity and support across the country reached a historical high and some political observers argued that Abiy was overwhelmingly more popular than the ruling party coalition, the EPRDF.[5]

Domestic policy

Since taking office in April 2018, Abiy's government has presided over the release of thousands of political prisoners from Ethiopian jails and the rapid opening of the country's political landscape.[66][67][68] In May 2018 alone the Oromo region pardoned over 7,600 prisoners.[69] On 29 May Ginbot 7 leader Andargachew Tsege, facing the death penalty on terrorism charges, was released after being pardoned by President Mulatu Teshome, along with 575 other detainees.[70]

That same day, charges were dropped against Andargachew's colleague Berhanu Nega and the Oromo dissident and public intellectual Jawar Mohammed, as well as their respectively affiliated US-based ESAT and OMN satellite television networks.[71] Shortly thereafter, Abiy took the "unprecedented and previously unimaginable" step of meeting Andargachew, who twenty-four hours previously had been on death row, at his office; a move even critics of the ruling party termed "bold and remarkable".[72] Abiy had previously met former Oromo Liberation Front leaders including founder Lencho Letta, who had committed to peaceful participation in the political process, upon their arrival at Bole International Airport.[73]

On 30 May 2018, it was announced the ruling party would amend the country's "draconian" anti-terrorism law, widely perceived as a tool of political repression. On 1 June 2018, Abiy announced the government would seek to end the state of emergency two months in advance of the expiration its six-month tenure, citing an improved domestic situation. On 4 June 2018, Parliament approved the necessary legislation, ending the state of emergency.[68] In his first briefing to the House of Peoples' Representatives in June 2018, Abiy countered criticism of his government's release of convicted "terrorists" which according to the opposition is just a name the EPRDF gives you if you are a part or even meet the "opposition". He argued that policies that sanctioned arbitrary detention and torture themselves constituted extra-constitutional acts of terror aimed at suppressing opposition.[74] This followed the additional pardon of 304 prisoners (289 of which had been sentenced on terrorism-related charges) on 15 June.[75]

The pace of reforms has revealed fissures within the ruling coalition, with hardliners in the military and the hitherto dominant TPLF said to be "seething" at the end of the state of emergency and the release of political prisoners.[76]

An editorial on the previously pro-government website Tigrai Online arguing for the maintenance of the state of emergency gave voice to this sentiment, saying that Abiy was "doing too much too fast".[77] Another article critical of the release of political prisoners suggested that Ethiopia's criminal justice system had become a revolving door and that Abiy's administration had quite inexplicably been rushing to pardon and release thousands of prisoners, among them many deadly criminals and dangerous arsonists.[78] On 13 June 2018, the TPLF executive committee denounced the decisions to hand over Badme and privatize SOEs as "fundamentally flawed", saying that the ruling coalition suffered from a fundamental leadership deficit.[79]

Transparency

In 2018, to expand the free press in Ethiopia, Abiy invited exiled media outlets to return.[80][81][82][83][84][85][86] One of the media outlets invited to return was ESAT (which had called for the genocide of Ethiopian Tigrayans).[87][88][89] However, since assuming office in April 2018, Abiy himself had, as of March 2019, only given one press conference,[90] on 25 August 2018 and around five months after he assumed office, where he answered questions from journalists. As of 21 March 2019,[update] he has not given another press conference where he has not refused to answer questions from journalists (rather than reading prepared statements).[91][92][93]

According to the NGOs Human Rights Watch, Committee to Protect Journalists and Amnesty International, Abiy's government has since mid 2019 been arresting Ethiopian journalists and closing media outlets (except for ESAT-TV).[94][95][96][97][98][99] From the international media outlets, his government has suspended the press license of Reuters's correspondent, and issued a warning letter to the correspondents of both BBC and Deutsche Welle for what the government described as "violation of the rules of media broadcasting".[100][101][102]

Economic reforms

In June 2018, the ruling coalition announced its intention to pursue the large-scale privatisation of state-owned enterprises and the liberalization of several key economic sectors long considered off-limits, marking a landmark shift in the country's state-oriented development model.[103]

State monopolies in the telecommunications, aviation, electricity, and logistics sectors are to be ended and those industries opened up to private sector competition.[104] Shares in the state-owned firms in those sectors, including Ethiopian Airlines, Africa's largest and most profitable, are to be offered for purchase to both domestic and foreign investors, although the government will continue to hold a majority share in these firms, thereby retaining control of the commanding heights of the economy.[105] State-owned enterprises in sectors deemed less critical, including railway operators, sugar, industrial parks, hotels and various manufacturing firms, may be fully privatised.[106]

Aside from representing an ideological shift with respect to views on the degree of government control over the economy, the move was seen as a pragmatic measure aimed at improving the country's dwindling foreign-exchange reserves, which by the end of the 2017 fiscal year were equal in value to less than two months worth of imports, as well as easing its growing sovereign debt load.[105][103]

In June 2018, Abiy announced the government's intention to establish an Ethiopian stock exchange in tandem with the privatization of state-owned enterprises.[107] As of 2015, Ethiopia was the largest country in the world, in terms of both population and gross domestic product, without a stock exchange.[108]

Foreign policy

In May 2018, Abiy visited Saudi Arabia, receiving guarantees for the release of Ethiopian prisoners including billionaire entrepreneur Mohammed Hussein Al Amoudi, who was detained following the 2017 Saudi Arabian purge.[66]

In June 2018, he met with Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in Cairo and, separately, brokered a meeting in Addis Ababa between the South Sudanese president Salva Kiir and rebel leader Riek Machar in an attempt to encourage peace talks.[109]

In December 2022, he attended the United States–Africa Leaders Summit 2022 in Washington, D.C., and met with US President Joe Biden.[110]

In February 2023, French President Emmanuel Macron welcomed Abiy Ahmed in Paris.[111] In April 2023, Abiy met with Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni in Addis Ababa.[112] In early May 2023, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz met with Abiy Ahmed in Addis Ababa to normalize relations between Germany and Ethiopia that had been strained by the Tigray War.[113]

In July 2023, Abiy attended the 2023 Russia–Africa Summit in Saint Petersburg and met with Russian President Vladimir Putin.[114][115]

Djibouti and port agreements

Since taking power Abiy has pursued a policy of expanding landlocked Ethiopia's access to ports in the Horn of Africa region. Shortly before his assumption of office it was announced that the Ethiopian government would take a 19% stake in Berbera Port in the Somaliland region located in northern Somalia as part of a joint venture with DP World.[116] In May 2018, Ethiopia signed an agreement with the government of Djibouti to take an equity stake in the Port of Djibouti, enabling Ethiopia to have a say in the port's development and the setting of port handling fees.[117]

Two days later a similar agreement was signed with the Sudanese government granting Ethiopia an ownership stake in the Port Sudan. The Ethio-Djibouti agreement grants the Djiboutian government the option of taking stakes in state-owned Ethiopian firms in return, such as the Ethiopian Airlines and Ethio Telecom.[118] This in turn was followed shortly thereafter by an announcement that Abiy and Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta had reached an agreement for the construction of an Ethiopian logistics facility at Lamu Port as part of the Lamu Port and Lamu-Southern Sudan-Ethiopia Transport Corridor (LAPSSET) project.[119]

The potential normalization of Ethiopia-Eritrea relations likewise opens the possibility for Ethiopia to resume using the Ports of Massawa and Asseb, which, prior to the Ethio-Eritrean conflict, were its main ports, which would be of particular benefit to the northern region of Tigray.[103] All these developments would reduce Ethiopian reliance on Djibouti's port which, since 1998, has handled almost all of Ethiopia's maritime traffic.[120][118]

Eritrea

Upon taking office, Abiy stated his willingness to negotiate an end to the Ethio-Eritrean conflict. In June 2018, it was announced that the government had agreed to hand over the disputed border town of Badme to Eritrea, thereby complying with the terms of the 2000 Algiers Agreement to bring an end to the state of tension between Eritrea and Ethiopia that had persisted despite the end of hostilities during the Ethiopia-Eritrea War.[103] Ethiopia had until then rejected the international boundary commission's ruling awarding Badme to Eritrea, resulting in a frozen conflict (popularly termed a policy of "no war, but no peace") between the two states.[121]

During the national celebration on 20 June 2018, the president of Eritrea, Isaias Afwerki, accepted the peace initiative put forward by Abiy and suggested that he would send a delegation to Addis Ababa. On 26 June 2018, Eritrean Foreign Minister Osman Saleh Mohammed visited Addis Ababa in the first Eritrean high-level delegation to Ethiopia in over two decades.[122]

In Asmara, on 8 July 2018, Abiy became the first Ethiopian leader to meet with an Eritrean counterpart in over two decades, in the 2018 Eritrea–Ethiopia summit.[123] The very next day, the two signed a "Joint Declaration of Peace and Friendship" declaring an end to tensions and agreeing, amongst other matters, to re-establish diplomatic relations; reopen direct telecommunication, road, and aviation links; and facilitate Ethiopian use of the ports of Massawa and Asseb.[124][125][126] Abiy was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019 for his efforts in ending the war.[3]

In practice, the agreement has been described as "largely unimplemented". Critics say not much has changed between the two nations. Among the Eritrean diaspora, many voiced disapproval for the Nobel Peace Prize focusing on the agreement with Eritrea when so little had changed in practice.[127] In July 2020, Eritrea's Ministry of Information said: "Two years after the signing of the Peace Agreement, Ethiopian troops continue to be present in our sovereign territories, Trade and economic ties of both countries have not resumed to the desired extent or scale."[128]

In October 2023, Abiy said that the secession of Eritrea from Ethiopia in 1993 was a historical mistake that threatens the existence of landlocked Ethiopia, saying that "In 2030 we are projected to have a population of 150 million. 150 million people can't live in a geographic prison."[129] He said Ethiopia has "natural rights" to direct access to the Red Sea and if denied, "there will be no fairness and justice and if there is no fairness and justice, it's a matter of time, we will fight".[130]

Calls to revoke Nobel Peace Prize

In June 2021, representatives from multiple countries called for the award of the Nobel Peace Prize to Abiy to be re-considered because of the war crimes committed in Tigray.[131][132] In an opinion piece, Simon Tisdall, one-time foreign editor of The Guardian, wrote that Abiy "should hand back his Nobel Peace Prize over his actions in the breakaway region".[133]

A person on a petition organization called Change.org launched a campaign to gather 35,000 signatures for revoking his Peace Prize; as of September 2021, nearly 30,000 have been obtained.[134]

Egypt

The dispute between Egypt and Ethiopia over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam has become a national preoccupation in both countries.[135][136] Abiy has warned: "No force can stop Ethiopia from building a dam. If there is need to go to war, we could get millions readied."[137]

After the murder of activist, singer and political icon Hachalu Hundessa ignited violence across Addis Ababa and other Ethiopian cities, Abiy hinted, without obvious suspects or clear motives for the killing, that Hundessa may have been murdered by Egyptian security agents acting on orders from Cairo to stir up trouble.[138] An Egyptian diplomat responded by saying that Egypt "has nothing to do with current tensions in Ethiopia".[139] Ian Bremmer wrote in a Time magazine article that Prime Minister Abiy "may just be looking for a scapegoat that can unite Ethiopians against a perceived common enemy".[138]

Religious harmony

Ethiopia is a country of various religious groups, primarily Christian and Muslim communities. Both inter-religious and intra-religious divisions and conflicts were a major concern, where both the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church and the Ethiopian Islamic Council experienced religious and administrative divisions and conflicts.[140][141] In 2018, he was given a special "peace and reconciliation" award by the Ethiopian Church for his work in reconciling rival factions within the church.[142]

Security sector reform

In June 2018, Abiy, speaking to senior commanders of the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) declared his intention to carry out reforms of the military to strengthen its effectiveness and professionalism, with the view of limiting its role in politics. This followed renewed calls both within Ethiopia and from international human rights groups, namely Amnesty International, to dissolve highly controversial regional militias such as the Liyyu force.[143] This move is considered likely to face resistance from TPLF hardliners, who occupy much of the military high command.[144]

Notably, he has also called for the eventual reconstitution of the Ethiopian Navy, dissolved in 1996 in the aftermath of Eritrea's secession after an extraterritorial sojourn in Djibouti, saying that "we should build our naval force capacity in the future."[145] It was reported that this move would appeal to nationalists still smarting from the country's loss of its coastline 25 years prior. Ethiopia already has a maritime training institute on Lake Tana as well as a national shipping line.

On 7 June 2018, Abiy carried out a wide-ranging reshuffle of top security officials, replacing ENDF Chief of Staff Samora Yunis with Lieutenant General Se'are Mekonnen, National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) director Getachew Assefa with Lieutenant General Adem Mohammed, National Security Advisor and former army chief Abadula Gemeda, and Sebhat Nega, one of the founders of the TPLF and director-general of the Foreign Relations Strategic Research Institute[146][147] Sebhat's retirements had been previously announced that May.[148]

Grenade attack

A large peaceful demonstration was organized in Addis Ababa at Meskel Square on 23 June 2018 to show support for the new prime minister. Just after Abiy had finished addressing the crowd a grenade was thrown and landed just 17 metres away from where he and other top officials were sitting. Two people were killed and over 165 were injured. Following the attack, 9 police officials were detained, including the deputy police commissioner, Girma Kassa, who was fired immediately. Questions were asked as to how a police car carrying attackers got so close to the prime minister and soon after the car was set alight destroying evidence. After the attack the prime minister addressed the nation on national TV unhurt by the blast and describing it as an "unsuccessful attempt by forces who do not want to see Ethiopia united". On the same day the prime minister made an unannounced visit to the Black Lion general hospital to meet victims of the attack.[149][150][151][152]

Cabinet reshuffle

In the parliamentary session held on 16 October 2018, Abiy proposed to reduce the number of ministries from 28 to 20 with half of the cabinet positions for female ministers, a first in the history of the country.[153] The new cabinet restructure included the first female president, Sahle-Work Zewde; the first female minister of the Ministry of Defense, Aisha Mohammed Musa;[154] the first female minister of the new Ministry of Peace, Muferiat Kamil responsible for the Ethiopian Federal Police and the intelligence agencies; the first female press secretary for the Office of the Prime Minister, Billene Seyoum Woldeyes.[155]

Internet shutdowns

According to NGOs like Human Rights Watch and NetBlocks, politically motivated Internet shutdowns have intensified in severity and duration under the leadership of Abiy Ahmed despite the country's rapid digitalization and reliance on cellular internet connectivity in recent years.[156][157] In 2020, Internet shutdowns by the Ethiopian government had been described as "frequently deployed".[158] Access Now said that shutdowns have become a "go-to tool for authorities to muzzle unrest and activism."[158] His government will cut internet as and when, "it's neither water nor air" have said Abiy.[159][160]

Political party reform

On 21 November 2019, upon approval of EPRDF ruling coalition, a new party, Prosperity Party, is formed via merging of three of the four parties that made up the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) and other five affiliate parties. The parties include the Oromo Democratic Party (ODP), the Southern Ethiopian People's Democratic Movement (SEPDM), the Amhara Democratic Party (ADP), the Harari National League (HNL), the Ethiopian Somali Peoples Democratic Party (ESPDP), the Afar National Democratic Party (ANDP), the Gambella Peoples Unity Party (GPUP), and the Benishangul Gumuz Peoples Democratic Party (BGPDP). The programs and bylaws of the newly merged party were first approved by the executive committee of EPRDF. Abiy believes that "Prosperity Party is committed to strengthening and applying a true federal system which recognizes the diversity and contributions of all Ethiopians".[161]

Civil conflicts

Awol Allo argues that when Abiy came to power in 2018, two irreconcilable and paradoxical vision future created. Central of these ideological vision often contradict historical narrative of Ethiopian state.[162] Abiy's undertook major reforms in the country and the liberation suspected to worsen the relationship with TPLF members.[163] The following lists detail civil conflicts and war during Abiy's premiership.

Amhara Region coup d'état attempt

On 22 June 2019, factions of the security forces of the region attempted a coup d'état against the regional government, during which the President of the Amhara Region, Ambachew Mekonnen, was assassinated.[164] A bodyguard siding with the nationalist factions assassinated General Se'are Mekonnen – the Chief of the General Staff of the Ethiopian National Defense Force – as well as his aide, Major General Gizae Aberra.[164] The Prime Minister's Office accused Brigadier General Asaminew Tsige, head of the Amhara region security forces, of leading the plot,[165] and Tsige was shot dead by police near Bahir Dar on 24 June.[166]

Metekel conflict

Starting in June 2019, fighting in the Metekel Zone of the Benishangul-Gumuz Region in Ethiopia has reportedly involved militias from the Gumuz people.[167] Gumuz are alleged to have formed militias such as Buadin and the Gumuz Liberation Front that have staged attacks.[168][169] According to Amnesty International, the 22–23 December 2020 attacks were by Gumuz against people from the Amhara, Oromo and Shinasha ethnic groups, who the Gumuz nationalists viewed as "settlers".[170]

October 2019 Ethiopian clashes

In October 2019, Ethiopian activist and media owner Jawar Mohammed claimed that members of the police had attempted to force his security detail to vacate the grounds of his home in Addis Ababa in order to detain him the night of 23 October, intimating that they had done so at the behest of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. The previous day, Abiy had given a speech in Parliament in which he had accused "media owners who don't have Ethiopian passports" of "playing it both ways", a thinly veiled reference to Jawar, adding that "if this is going to undermine the peace and existence of Ethiopia... we will take measures."[171][172]

Hachalu Hundessa riots

The murder of Oromo singer Hachalu Hundessa led serious unrest across Oromia Region and Addis Ababa from 30 June to 2 July 2020. The riots lead to the deaths of at least 239 people according to initial police reports.[173]

Tigray War

In early November 2020, an armed conflict began after TPLF security forces attacked the ENDF Northern Command headquarters, prompting the ENDF to engage in war. The ENDF was supported by Eritrean Defence Force, Amhara and Afar Region special force with other regional forces, while TPLF was aided by Tigray Special Force which later became the Tigray Defense Forces.[174][175][176][177][178][179][180][181] Hostilities between the central government and the TPLF escalated after the TPLF rejected the central government's decision to postponing August 2020 elections to mid-2021 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, accusing the government of violating the Ethiopian constitution.[182]

The TPLF carried out its own regional elections, winning all contested seats in the region's parliament.[183] In response, Abiy Ahmed redirected funding from the top level of the Tigray regional government to lower ranks in a bid to weaken the TPLF party.[184]

The central matter of the civil conflict, as portrayed by Abiy and as reported by Seku Ture, a member of the TPLF party, is an attack on the Northern Command bases and headquarters in the Tigray region by security forces of the TPLF,[185][186][187] the province's elected party; though such a claim is contested.

The Ethiopian government announced on 28 November 2020 that they had captured Mekelle, the capital of Tigray, completing their "rule of law operations".[188] However, there are reports that guerrilla-style conflict with the TPLF continues.[189][190]

About 2.3 million children are cut off from desperately needed aid and humanitarian assistance, said the United Nations. The Ethiopian federal government has made strict control of access to the Tigray region (since the start of the conflict), and the UN said it is frustrated that talks with the Ethiopian government have not yet brought humanitarian access. These include, "food, including ready-to-use therapeutic food for the treatment of child malnutrition, medicines, water, fuel and other essentials that are running low" said UNICEF.[191][192][193][194][195]

On 18 December 2020, looting was reported by EEPA, including 500 dairy cows and hundreds of calves stolen by Amhara forces.[196] On 23 November, a reporter of AFP news agency visited the western Tigray town of Humera, and observed that the administration of the conquered parts of Western Tigray was taken over by officials from Amhara Region.[197] Refugees interviewed by Agence France Presse (AFP) stated that pro-TPLF forces used Hitsats as a base for several weeks in November 2020, killing several refugees who wanted to leave the camp to get food, and in one incident, killed nine young Eritrean men in revenge for having lost a battle against the EDF.[198]

In his premature[199][200][201][202][203][204] victory speech delivered to the federal parliament[205] on 30 November 2020, Abiy Ahmed pronounced: "Related to civilian damage, maximum caution was taken. In just 3 weeks of fighting, in any district, in Humera, Adi Goshu, ... Axum, ..., Edaga Hamus, .... The defence forces never killed a single civilian in a single town. No soldier from any country could display better competence."[206]

On 21 March 2021, during a parliamentary session in which Abiy Ahmed was questioned on sexual violence in the Tigray War, he replied: "The women in Tigray? These women have only been penetrated by men, whereas our soldiers were penetrated by a knife".[207]

The public image of Abiy Ahmed is being rapidly re-assessed by international media as increasingly grisly reports of atrocities emerge.[208] The US Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, has been quoted as saying that he had seen "very credible reports of human rights abuses and atrocities", and that "forces from Eritrea and Amhara must leave and be replaced by 'a force that will not abuse the human rights of the people of Tigray or commit acts of ethnic cleansing'." In December 2021, Declan Walsh reported in The New York Times that Abiy and Isaias had been secretly planning the Tigray War even before the former's Nobel Prize was awarded, in order to settle their grudges against the TPLF.[209]

According to researchers at Ghent University in Belgium, as many as 600,000 people had died as a result of war-related violence and famine by late 2022.[210]

War in Amhara

In early April 2023, a disagreement occurred between the Ethiopian federal government and Amhara regional forces, particularly the Fano militia following the EDNF army raided to Amhara Region to disarm regional and paramilitary forces. On 9 April, large protests erupted in Gondar, Kobo, Seqota, Weldiya and other cities where the protestors block roads to deter the army to enter. On 4 May, the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC) reported that there is militarized situations in the area of North Gondar, North Wollo and North Shewa zones in the town of Shewa Robit, Armania, Antsokiyana Gemza and Majete.[211]

Further skirmishes led to series clashes between the Fano militia and ENDF in August while ENDF troops attempted to push back Fano unit from seizing Debre Tabor and Kobo. After Fano captured Lalibela, the Amhara Regional Governor Yilkal Kefale request help from ENDF to suppress Fano aggression, resulted in a six-months state of emergency issued by the federal government on 4 August. According to EHRC, in 4 densely populated kebeles in Debre Birhan, civilians including in a hospital, church, and school as well as residents in their neighborhoods and workers in their workplaces apparently killed due to fragments from heavy artillery or in crossfire between 6 and 7 August 2023. Crossfire was imminent in Debre Birhan IDPs, particularly in China IDPs site near Kebele 8 hosts close to 13,000 people.[212]

The conflict also spread into Oromia Region since 26 August 2023, after Fano and the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) engagement in Dera.[213] Human rights violation often burdened toward ethnic Amhara who reportedly subjected to mass arbitrary arrest as the urban center of the Amhara region cities under military command post position.[214] Between 25 August and 5 September 2023, EHRC found that many civilians were killed, physically injured, and their properties destroyed in the area of Debre Markos in East Gojjam Zone, Adet and Merawi in North Gojjam Zone; Debre Tabor in South Gondar Zone; Delgi in Central Gondar Zone; Majetie, Shewa Robit and Antsokiya towns in North Shewa Zone.[215]

Political positions

Abiy has been described as a "liberal populist" by the academic and journalist Abiye Teklemariam and the influential Oromo activist Jawar Mohammed.[citation needed] Alemayehu Weldemariam, a U.S.-based Ethiopian lawyer and public intellectual, has called Abiy "an opportunistic populist jockeying for power on a democratizing platform."[216] On the other hand, Tom Gardner argues in Foreign Policy that he's not a populist, but more of a liberal democrat. However, Gardner acknowledges that Abiy has "occasionally used language that can be read as euphemistic and conspiracy-minded", and might have "exploited the system's vulnerabilities, such as a pliable media and politicized judiciary, for his own ends."[216]

Criticism

Abiy's government was accused of authoritarianism and restricting freedom of the press, especially since the start of the Tigray War. Numerous watchdogs and human rights groups accused Abiy's government of "increasingly intimidating" the media as well as harassing opponents to propel unrest.[217] In 2019 World Press Freedom Index, Ethiopia improved the rank by jumping forty positions from 150 to 110 out of 180 countries.[218]

In 2021, 46 journalists were detained, making Ethiopia the worst jailers in Africa. Journalist Gobeze Sisay was arrested by unknown plainclothes officers in his home on 1 May. On 3 May, the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC) released statement about Gobez Sisay's whereabout.[219][220][221][222] Similarly, the founder of Terara Network was arrested in Addis Ababa on 10 December 2021 in allegation of "disseminating misinformation", which was transferred to Sabata Daliti police station in Oromia Special Zone. He was released on 5 April 2022 with bail of 50,000 Ethiopian birr.[223][224][225]

Blockade of the Tigray region

In August 2021, USAID accused Abiy's government of "obstructing" access to Tigray.[226] In early October 2021, nearly a year after the Tigray War started, Mark Lowcock, who led OCHA during part of the Tigray War, stated that the government of Abiy Ahmed was deliberately starving Tigray, "running a sophisticated campaign to stop aid getting in" and that there was "not just an attempt to starve six million people but an attempt to cover up what's going on."[227] WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus called the blockade by Ethiopia "an insult to our humanity".[228]

Awards

| # | Award | Awarding institution | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Most Excellent Order of the Pearl of Africa: Grand Master[229] | Uganda | 9 June 2018 |

| 2 | Order of the Zayed Medal[230] | UAE Crown Prince | 24 July 2018 |

| 3 | High Rank Peace Award[231] | Ethiopian Orthodox Church | 9 September 2018 |

| 4 | Order of King Abdulaziz[232] | Kingdom of Saudi Arabia | 16 September 2018 |

| 5 | Nominee for Tipperary International Peace Award alongside Mary Robinson (the eventual winner); Aya Chebbi; humanitarian worker in South Sudan Orla Treacy; the President of Eritrea, Isaias Afwerki; Swedish student and climate change activist Greta Thunberg Cherinet Hariffo Education Advocate From Ethiopia and Nigerian humanitarian activist Zannah Mustapha[233] | Tipperary Peace Convention | November 2018 |

| 6 | 100 Most Influential Africans of 2018[234] | New African magazine | 1 December 2018 |

| 7 | African of the year[235] | The African leadership magazine | 15 December 2018 |

| 8 | The 5th Africa Humanitarian and Peacemakers Award (AHPA)[236] | African Artists for Peace Initiative | 2018 |

| 9 | 100 Most Influential People 2018[237] | Time magazine | 1 January 2019 |

| 10 | 100 Global Thinkers of 2019[238] | Foreign Policy magazine | 1 January 2019 |

| 11 | Personality of the Year[239] | AfricaNews.com | 1 January 2019 |

| 12 | African Excellence Award for Gender[240] | African Union | 11 February 2019 |

| 13 | Humanitarian and Peace Maker Award[241] | African Artists Peace Initiative | 9 March 2019 |

| 14 | Laureate of the 2019 edition of the Félix Houphouët-Boigny – UNESCO Peace Prize[242] | UNESCO | 2 May 2019 |

| 15 | Peace Award for Contribution of Unity to Ethiopian Muslims[243] | Ethiopian Muslim Community | 25 May 2019 |

| 16 | Chatham House Prize 2019 Nominee[244] | Chatham House – The Royal Institute of International Affairs | July 2019 |

| 17 | World Tourism Award 2019[245] | World Tourism Forum | August 2019 |

| 18 | Hessian Peace Prize[246] | State of Hessen | August 2019 |

| 19 | African Association of Political Consultants Award[247] | APCAfrica | September 2019 |

| 20 | Nobel Peace Prize[248] | Nobel Foundation | 11 October 2019 |

| 21 | GIFA Laureate 2022 [249] - Global Islamic Finance Award | Global Islamic Finance Awards | 14 September 2022 |

| 22 | Outstanding African Leadership Award[250][251] Award for Green Legacy Initiative | American Academy of Achievement and Global Hope Coalition | 13 December 2022 |

| 23 | FAO Agricola Medal[252][253] | UN's Food and Agriculture Organization | 28 Jan 2024 |

References

- ^ "Prime Minister". The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia's Office of the Prime Minister. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

H.E. Abiy Ahmed Ali (PhD) is the fourth Prime Minister of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia

- ^ a b "Dr Abiy Ahmed sworn in as Prime Minister of Ethiopia". Fana Broadcasting. 1 April 2018. Archived from the original on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ a b Busby, Mattha; Belam, Martin (11 October 2019). "Nobel peace prize: Ethiopian prime minister Abiy Ahmed wins 2019 award – as it happened". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ "Abiy Ahmed prime minister of Ethiopia", Encyclopedia Britannica, archived from the original on 10 November 2019, retrieved 10 February 2021

- ^ a b c "EPRDF elects Abiy Ahmed chair". The Reporter. 27 March 2018. Archived from the original on 27 March 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ "Ethiopia's ODP picks new chairman in bid to produce next Prime Minister". Africa News. 22 February 2018. Archived from the original on 9 December 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ Abiy Ahmed: Ethiopia's prime minister, BBC News, 28 March 2018, archived from the original on 11 October 2019, retrieved 11 October 2019

- ^ Schwikowski, Martina (16 June 2020). "Crisis looms in Ethiopia as elections are postponed". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ Endeshaw, Dawit (21 June 2019). "Ethiopia opposition see dangers if 2020 vote delayed". Reuters. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ "Ethiopia is entering constitutional limbo". The Economist. 16 May 2020. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ "Preliminary Statement: African Union Election Observation Mission to the 21 June 2021 General Elections in the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia | African Union". au.int. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ "Rise and fall of Ethiopia's TPLF – from rebels to rulers and back". The Guardian. 25 November 2020. Archived from the original on 15 February 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ "Ethiopia's Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed: Peacemaker or Authoritarian?". www.democratic-erosion.com. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ Teshome, Moges Zewdu (15 June 2023). "Charming Abiy Ahmed, a very modern dictator". Ethiopia Insight. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ "Ethiopia: News - Amhara Opposition Party Requests PM Abiy to Appear Before Lawmakers, Parliament Session On Recent Killing in Western Oromia". AllAfrica. 25 June 2022. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

The opposition National Movement of Amhara (NaMA) requested Speaker of the House of People's Representatives, Tagesse Chafo, to call on Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed to appear before Parliament to explain why his government is "unable to stop the ongoing genocide against the people of Amhara, and why it has not been able to provide adequate support to the victims who are displaced by the recent attack in Western Oromia, at a time when PM Abiy Ahmed and his government repeatedly state that "they have built the capacity and enough security forces to ensure the security of our country and its people."

- ^ "Statement on the Ongoing Violence Against the Amhara People". lemkininstitute.com.

Since 2018, when the Oromo-backed Prosperity Party came into power (led by 2019 Nobel Prize laureate Abiy Ahmed Ali), the Amhara people have continued to suffer severely, and their fundamental human rights have been heavily violated. Abiy's government amnestied previously exiled OLA members. The atrocity crimes committed against the Amhara people since 2018 include mass killings and summary executions, ethnic cleansing, abduction of children, forced disappearances, measures intended to prevent births, the forcible transfer of children of the group to another group, rape and other forms of sexual violence, and looting.

- ^ Harding, Andrew (21 November 2021). "Ethiopia's Tigray conflict: Mass arrests and ethnic profiling haunt Addis Ababa". BBC News. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ "More than 4,000 arrested in Amhara as Ethiopia cracks down on militia". The Guardian. 30 May 2022. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ Tzabiras, Marianna (14 June 2022). "Mass arrest of journalists in Ethiopia". IFEX. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ Paravicini, Giulia (23 February 2024). "In Ethiopia, a secret committee orders killings and arrests to crush rebels". Reuters. Retrieved 29 November 2024.

- ^ Account (23 February 2024). "Koree Nageenyaa - secret gov't body -behind executions in Oromia : report". Borkena Ethiopian News. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ OGF (8 March 2024). "The "Koree Nageenyaa's" Brutality Echoes Gestapo Tactics: members of Ethiopia's State Terror group must be held accountable". Oromia Global Forum (OGF). Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Endeshaw, Dawit (31 March 2018). "The rise of Abiy 'milion' Ahmed". The Reporter. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ "Prime Minister". pmo.gov.et. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- ^ "Abiy Ahmed Ali". DW.com (in Swahili). 28 March 2018. Archived from the original on 6 May 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

Abiy Ahmed alizaliwa August 15, 1976 nchini Ethiopia (Abiy Ahmed was born on August 15, 1976 in Ethiopia)

- ^ Girma, Zelalem (31 March 2015). "Ethiopia in democratic, transformational leadership". Ethiopian Herald. Archived from the original on 6 May 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ a b Sengupta, Somini (17 September 2018). "Can Ethiopia's New Leader, a Political Insider, Change It From the Inside Out?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ a b c OBN, Oromia (15 July 2020). "Dr Abiyyi Ahimad turtii OBN waliin taasisan". Youtube. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ "The Guardian view on Ethiopia: change is welcome, but must be secured". The Guardian. 7 January 2019. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 21 August 2019. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Endeshaw, Dawit (31 March 2018). "The rise of Abiy "Abiyot" Ahmed". The Reporter. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

Abiy's mother, Tezeta Wolde, a converted Christian from Burayu, Finfine Special Zone, Oromia Regional State, was the fourth wife for Ahmed. Together they have six children with Abiy being the youngest.

- ^ "First Lady". FDRE Office of the Prime Minister. Archived from the original on 31 August 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Dr Abiy Ahmed interview with Amhara TV". ZeHabesha TV. 21 November 2017. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2019 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Manek, Nizar (4 April 2018). "Can Abiy Ahmed save Ethiopia?". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 4 April 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ Shellnutt, Kate (11 October 2019). "Ethiopia's Evangelical Prime Minister Wins Nobel Peace Prize". News & Reporting. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "God wants Ethiopians to prosper: The prime minister and many of his closest allies follow a fast-growing strain of Christianity". The Economist. 24 November 2018. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ a b በኦሮሚያ ብሄራዊ ክልላዊ መንግስት ካቢኒ አባልነት የተሾሙት እነማን ናቸው? [Who are the Cabinet members in the Oromia Regional State?]. FanaBC (in Amharic). Archived from the original on 20 February 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ "A brief profile about Dr. Abiy Ahmed". Walta Media and Communication Corporate. 28 March 2018. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ "Dr. Abiy Ahmed's Ethiopia: Anatomy of an African enigmatic polity". 17 May 2018. Archived from the original on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ "Biography of Abiy Ahmed PRIME MINISTER OF ETHIOPIA". Archived from the original on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ "Ali Honorary Degree Board Package" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ "IPSS Student named to Ethiopia's Cabinet". IPSS Addis. 12 October 2015. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ a b Ahmed, Abiy (2016). "Social capital and its role in traditional conflict resolution: the case of inter-religious conflict in Jimma Zone of the Oromia Regional State in Ethiopia" (PDF). Addis Ababa University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 May 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ a b de Waal, Alex (4 May 2022). "Abiy Ahmed—PhD?". World Peace Foundation. Archived from the original on 22 June 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Abiy Ahmed | Biography, Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 10 November 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d Ahmed, Abiy (1 August 2017). "Countering Violent Extremism through Social Capital: Anecdote from Jimma, Ethiopia". Horn of Africa Bulletin. 29 (4): 12–17. ISSN 2002-1666. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ Alex de Waal; Jan Nyssen; Gebrekirstos G. Gebremeskel; Boudewijn François Roukema; Rundassa Eshete (12 April 2023), Plagiarism in Abiy Ahmed’s PhD Thesis: How will Addis Ababa University handle this?, World Peace Foundation, Wikidata Q117600374, archived from the original on 12 April 2023

- ^ Endeshaw, Dawit (31 March 2018). "The rise of Abiy "Abiyot" Ahmed". The Reporter. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

For some time the EPRDF, was in talks with the OLF; in fact, the later was part of the then transitional government. OLF was, at the time, very popular in Oromia region. However, the peaceful talks failed to bear fruit as things turn to become violent. That was when alternative forces like the Oromo People's Democratic Organization (OPDO) came to the fore.

According to people who witnessed that critical period, the OLF had strong support in Agaro like most parts of Oromia region (No statistical evidence exists to support this claim).

It was at that time that Abiy's family was directly affected by the political transition in the country. Abiy's father and his eldest son, Kedir Ahmed, were arrested for some time.

Unfortunately, Kedir was killed during that time in what was believed to be a politically motivated assassination, according to people close to the family.

By the time, Agaro, which now has a population of, 41,085, was believed to be a stronghold of the OLF.

"I think losing his brother at that age was a turning point in Abiy's life," Miftah Hudin Aba Jebel, a childhood friend of Abiy, told The Reporter. "I mean we were young and I remember one night Abiy asking me to join the struggle," he recalls. "To be honest, it was difficult for me to understand what he was saying."

According to multiple sources, Abiy joined the struggle during early 1991, just a few months before the downfall of the military regime, almost at the age of 15.

"By the time we were teenagers; Abiy, another young man by the name Komitas, who was a driver for Abadula Gemeda at the time, and myself joined the OPDO," Getish Mamo, the then member of OPDO's music band called Bifttu Oromia, told The Reporter. "We were also close with Abadula Gemeda." Abadula was one of the founders of the OPDO and current speaker of the House of People's Representatives.

Abiy, at the time, was working as a radio operator, according to Getish. - ^ "Dr. Abiy Ahmed's must listen speech on knowledge, ideas and concepts". Borkena.com. 11 January 2018. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ a b "Nobel Peace Prize: Ethiopia PM Abiy Ahmed wins". BBC News. 11 October 2019. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ Mackay, Maria (1 December 2006). "Muslim Mob Kills Six Christians In Ethiopia". Christianity Today. Archived from the original on 10 May 2007. Retrieved 14 July 2007.

- ^ "About Us". Oromo Democratic Party. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ "About STIC". Stic.gov.et. Archived from the original on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ a b "Dr Abiy Ahmed: a biography". Eritrea Hub. 7 November 2018. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ a b c "Ethiopia: Who is new Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali?". Deutsche Welle. 29 March 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ a b "Exciting opportunity for investors in Oromia State". Ethiopian Herald. Archived from the original on 20 February 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ "Oromia Committed to Support Domestic Investors: Chief Administrator Lemma Megersa". ena.gov.et. Archived from the original on 20 February 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ "ኦሮሚያ፣ የ"ኢኮኖሚ አብዮት"" [Oromia, the "Economy Revolution"]. Deutsche Welle (in Amharic). 10 March 2017. Archived from the original on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ "What is behind clashes in Ethiopia's Oromia and Somali regions?". BBC News. 18 September 2017. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ "Amhara Mass Media Agency". Facebook.com. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ "Who will become Ethiopia's new prime minister and how?". The East African. 17 February 2018. Archived from the original on 18 February 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ Allo, Awol K. "Ethiopia's state of emergency 2.0". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ Endeshaw, Dawit (4 November 2017). "Movers and Shakers!!!". The Reporter. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ "Abiy Ahmed elected as chairman of Ethiopia's ruling coalition". Al Jazeera. 28 March 2018. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ "Ethiopia: Dr. Abiy Ahmed tipped to become next PM". Journal du Cameroun. 23 February 2018. Archived from the original on 13 March 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ "Seven people who could be Ethiopia's next leader". BBC News. 16 March 2018. Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ a b "Abiy Ahmed pulls off an astonishing turnaround for Ethiopia". The Washington Post. 10 June 2018. Archived from the original on 11 June 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ^ Soleiman, Ahmend (27 April 2018). "Ethiopia's Prime Minister Shows Knack for Balancing Reform and Continuity". Chatham House. Archived from the original on 1 May 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ a b Dahir, Abdi Latif (4 June 2018). "Ethiopia will end its state of emergency early, as part of widening political reforms". Quartz. Archived from the original on 5 June 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ "Ethiopia's Oromia regional state pardons 7,611 detainees". Xinhua. 24 May 2018. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "Ethiopia frees abducted Briton Andargachew Tsege on death row". BBC News. 29 May 2018. Archived from the original on 30 May 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "Ethiopia drops charges against 2 US-based broadcasters". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 29 May 2018. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ Zelalem, Zecharias (31 May 2018). "Ethiopia's PM Abiy Ahmed 'breaks the internet' with photo of Andargachew Tsige meeting". OPride. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ Standard, Addis (24 May 2018). "PM #AbiyAhmed met today with the leadership of ODF". Twitter – @addisstandard. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ Mumbere, Daniel (19 June 2018). "Ethiopia PM says era of state sanctioned torture is over". AfricaNews. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ "Ethiopia pardons hundreds sentenced on 'terrorism' charges". Al Jazeera. Reuters. 15 June 2018. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ Bruton, Bronwyn (6 June 2018). "The announcement that Ethiopia will give up Badme..." Twitter. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "Lift the state of emergency in Ethiopia, and lose the country". Tigrai Online. 2 June 2018. Archived from the original on 7 June 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ Gebre, Seifeselassie (28 May 2018). "Is Ethiopia Creating a Revolving Door Criminal Justice System?". Tigrai Online. Archived from the original on 2 June 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ Abera, Etenesh (13 June 2018). "TPLF says Ethiopia's recent Eritrea, economy related decisions have "fundamental flaws"; calls for emergency meeting of EPRDF executive". Addis Standard. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ "One year on, tough times loom for Ethiopia's Abiy Ahmed". Yahoo! News. 31 March 2019. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

... Abiy has touted his moves to improve media freedom – following in the footsteps of Hailemariam, who released several prominent jailed journalists – but instability threatens this progress.

- ^ "Ethiopia drops charges against two foreign based media organizations, two individuals". FanaBC. 29 May 2018. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

The Federal Attorney General has requested the federal high court to drop charges against two foreign countries-based media organizations-ESAT and OMN as well as Berhanu Nega and Jawar Mohammed.

- ^ "New television channels in Ethiopia may threaten state control". The Economist. 9 December 2016. Archived from the original on 12 January 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ Yoseph, Nardos (2 August 2009). "New Channels Abundance Increases Competition for TV Ad Revenues". Addis Fortune. Archived from the original on 21 April 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ Roth, Kenneth (19 December 2018). "Ethiopia: Events of 2018". World Report 2019. Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 19 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

After years of widespread protests against government policies, and brutal security force repression, the human rights landscape transformed in 2018 after Abiy Ahmed became prime minister in April. The government lifted the state of emergency in June and released thousands of political prisoners from detention, including journalists and key opposition leaders such as Eskinder Nega and Merera Gudina. The government lifted restrictions on access to the internet, admitted that security forces relied on torture, committed to legal reforms of repressive laws and introduced numerous other reforms, paving the way for improved respect for human rights... Parliament lifted the ban on three opposition groups, Ginbot 7, Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), and Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) in June. The government had used the proscription as a pretext for brutal crackdowns on opposition members, activists, and journalists suspected of affiliation with the groups. Many members of these and other groups are now returning to Ethiopia from exile...

With the ruling Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) controlling 100 percent of the seats in parliament, the institutional and legal impediments for sustained political space remain a challenge. Accountability for years of abuses, including torture and extrajudicial killings, and opening the space for political parties and civil society remain significant challenges for the new administration. There are indications that the reform process may ultimately be hindered by a lack of independent institutions to carry forward changes...

Ethiopia released journalists who had been wrongfully detained or convicted on politically motivated charges, including prominent writers such as Eskinder Nega and Woubshet Taye, after more than six years in jail. The federal Attorney General's Office dropped all pending charges against bloggers, journalists and diaspora-based media organizations, including the Zone 9 bloggers, Ethiopian Satellite Television (ESAT), and Oromia Media Network (OMN), which had previously faced charges of violence inciting for criticizing the government...

OMN and ESAT television stations reopened in Addis Ababa in June, following calls by Prime Minister Abiy for diaspora-based television stations to return. Additionally, the government lifted obstructions to access to more than 250 websites. The restriction on access to the internet and mobile applications introduced during the 2015 protests was also lifted. - ^ Latif Dahir, Abdi (14 December 2018). "For the first time in decades, there are no Ethiopian journalists in prison". Quartz Africa. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

...Abiy Ahmed, who took over in April also released thousands of political prisoners and journalists and dismissed charges against diaspora-based media outlets. Those released included prominent journalists Eskinder Nega, Darsema Sori, and Khalid Mohammed, who were held for years on charges ranging from treason to inciting extremist ideology and planning to overthrow the government.

- ^ Bieber, Florian; Tadesse Goshu, Wondemagegn (15 January 2019). "Don't Let Ethiopia Become the Next Yugoslavia". Foreign Policy. Graham Holdings Company. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

The process of liberalizing a political system in an ethnically polarized society is dangerous. During the liberalizing moment, newfound freedom of speech can easily focus on finding culprits, singling out particular groups, and bringing up repressed grievances. Furthermore, there is less tradition to distinguish fact from rumor, and thus fearmongering rhetoric can travel quickly and with fewer checks than in established pluralist environments. This is mostly due to social media but also because of a lack of reliable institutions and structures to turn to in a country where institutions have been decimated by years of authoritarian rule.

- ^ "Why ESAT and Messay Mekonen called for genocide on the people of Tigray?". Horn Affairs. 15 November 2016. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

Mr. Messay Mekonon has called a genocide attack to such civil population, which are the indigenous people of Tigray-Ethiopia in his satellite TV called ESAT on 4 September 2016

- ^ "ESAT Radio and Television: The Voice of Genocide". Horn Affairs. 23 August 2017. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

ESAT television, in a public address it made to the people of Gondar, on August 06, 2016, ESAT journalist Mesay Mekonnen broadcast that "the difficulty that we (Ethiopians) are facing now is not between the oppressor government/regime and the oppressed people, as other countries are facing. What we Ethiopians are now facing is between a small minority ethnic group, representing five percent of the Ethiopian population, who wants to rule Ethiopia subjugating others and the subjugated peoples. And the solution for what we are facing at this time is "drying the water so as to catch (kill) the fish."

- ^ "ESAT TV, stop your hate propaganda against the people of Tigrai". Tigrai Online. 27 January 2013. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

ESAT's main objective is to provide thinly veiled poisonous hate propaganda against the people of Tigrai. Financed by the traditional enemies of Ethiopia this divisive and very dangerous media outlet has been pumping out thousands of articles, cyber TV programs and radio programs. Majority of those programs are designed to create a permanent discord between the general Ethiopian population and the people of Tigrai.

- ^ "Press freedom in Ethiopia has blossomed. Will it last?". The Economist. 16 March 2019. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

Two tests of the new opening loom. The first is the willingness of state media to give equal time to the prime minister and his opponents in elections next year. Another will be the openness of Abiy himself to scrutiny: he has given only one press conference and few interviews.

- ^ "PM Abiy holds his first ever press conference since inauguration". Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation. 25 August 2018. Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "Ethiopians are going wild for Abiy Ahmed". The Economist. 18 August 2018. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

Ethiopia's state media behave slavishly towards the prime minister, obsessively covering his appearances and seldom airing critical views. Mr Abiy himself never gives interviews and has yet to hold a press conference. Non-state outlets complain that they are no longer invited to official press briefings.

- ^ "Nobel peace prize winner Abiy Ahmed embroiled in media row". The Guardian. 8 December 2019. Archived from the original on 12 December 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

Senior officials of the Norwegian Nobel Institute have said the 2019 winner's refusal to attend any event where he could be asked questions publicly is "highly problematic". Olav Njølstad, the secretary of the Nobel committee, said it would "very much have wanted Abiy to engage with the press during his stay in Oslo". "We strongly believe that freedom of expression and a free and independent press are vital components of peace … Moreover, some former Nobel peace prize laureates have received the prize in recognition of their efforts in favour of these very rights and freedoms," he said. Nobel peace prize laureates traditionally hold a news conference a day before the official ceremony, but Abiy has told the Norwegian Nobel committee he does not intend to do so.

- ^ "Ethiopia: Release detained journalists and opposition politicians immediately". Amnesty International. 7 April 2020. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "Ethiopian authorities arrest Addis Standard editor Medihane Ekubamichael". Committee to Protect Journalists. 13 November 2020. Archived from the original on 12 December 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "Ethiopian journalist Yayesew Shimelis detained following COVID-19 report". Committee to Protect Journalists. April 2020. Archived from the original on 8 December 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2020.