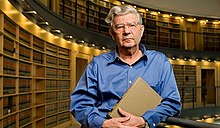

Aharon Barak

Aharon Barak | |

|---|---|

| אהרן ברק | |

| |

| President of the Supreme Court of Israel | |

| In office 13 August 1995 – 14 September 2006 | |

| Preceded by | Meir Shamgar |

| Succeeded by | Dorit Beinisch |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 16 September 1936 Kaunas, Lithuania |

| Nationality | Israeli |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 4 |

| Parent(s) | Zvi Brick, Leah Brick |

| Alma mater | Hebrew University of Jerusalem |

| Signature |  |

Aharon Barak (Hebrew: אהרן ברק; born 16 September 1936) is an Israeli lawyer and jurist who served as President of the Supreme Court of Israel from 1995 to 2006. Prior to this, Barak served as a Justice of the Supreme Court of Israel from 1978 to 1995, and before this as Attorney General of Israel from 1975 to 1978.

Barak was born with the name of Erik Brick in Kaunas, Lithuania in 1936. Having survived the Holocaust, he and his family later immigrated to Mandatory Palestine in 1947. He studied law, international relations and economics at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and obtained his Bachelor of Laws in 1958. Between 1958 and 1960, he was drafted into the Israeli military.

From 1974 to 1975, Barak was dean of the law faculty of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.[1] Barak is currently a law professor at Reichman University in Herzliya, and has taught at institutions including Yale Law School, Central European University, Georgetown University Law Center, and the University of Toronto Faculty of Law.

Biography

[edit]Erik Brick (later Aharon Barak) was born in Kaunas, Lithuania, the only son of Zvi Brick, an attorney, and his wife Leah, a teacher. After the Nazi occupation of the city in 1941, the family was in the Kovno ghetto. In an interview with HaOlam HaZeh, Barak told how a Lithuanian farmer saved his life by hiding him under a load of potatoes and smuggling him out of the ghetto, thereby risking his own life if caught.[2] At the end of the war, after wandering through Hungary, Austria, and Italy, Barak and his parents reached Rome, where they spent the next two years. In 1947, they received travel papers and immigrated to Mandatory Palestine. After a brief period in a moshav, the family settled in Jerusalem.[citation needed]

He studied law, international relations and economics at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and obtained his Bachelor of Laws in 1958. Between 1958 and 1960, having been drafted into the Israeli Defense Forces, he served in the office of the Financial Advisor to the Chief of Staff. Upon discharging his service he returned to the Hebrew University, where he completed his doctoral dissertation with distinction in 1963. Simultaneously he began work as an intern at the Attorney General's office. When the Attorney General began dealing with the trial of Adolf Eichmann, Barak, being a Holocaust survivor, preferred not to be involved in the work. At his request, he was transferred to the State Attorney's office to complete his internship. Upon completing his internship he was recognised as a certified attorney.

Barak is married to Elisheva Barak-Ussoskin, former vice president of the National Labor Court, with whom he has three daughters and a son, all trained in the law.[3] Barak's son-in-law Ram Landes made a one-hour documentary film about Barak in 2009 called The Judge (השופט), based on an in-depth interview with Barak.

Academic career

[edit]Between 1966 and 1967 Barak studied at Harvard University. In 1968 he was appointed as a professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and in 1974 was named the dean of its law faculty. In 1975, at age 38, he was awarded the Israel Prize for legal research. In the same year he became a member of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. In 1978 he became a foreign member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

After his retirement from the Supreme Court, Barak joined the staff of the Reichman University in Herzliya, and he teaches in the master's degree program for Commercial Law. He also lectures in the Bachelor of Laws program. In addition, he continues to lecture at both the Yale Law School and the University of Alabama in the United States, as well as lecturing as a Distinguished Visitor at the University of Toronto Faculty of Law.

Judicial career

[edit]Attorney General of Israel

[edit]Between 1975 and 1978, Barak served as the Attorney General of Israel. Among his well-known decisions in this capacity were:

- The decision to launch a criminal investigation against Asher Yadlin, CEO of Clalit Health Services and a nominee for the position of director of the Bank of Israel. Yadlin was convicted of accepting a bribe and sentenced to 5 years imprisonment. During this incident Barak coined the so-called Buzaglo test.

- The decision to continue with the police investigation of Housing and Construction Minister Avraham Ofer, despite the Minister's request that the investigation be terminated. Ofer committed suicide in 1977, prior to the conclusion of the investigation.

- The decision to prosecute Leah Rabin due to the Dollar Account affair. This decision brought about the resignation of the Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. In justifying his decision not to prosecute Yitzhak Rabin for the affair, Barak has argued that "Rabin was severely punished in that he was forced to resign from his position. There was no room to punish him further."

Barak was appointed by Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin in 1978 as the legal advisor to the Israeli delegation for negotiating the Camp David Accords. In his book Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid, Jimmy Carter praises Barak as a negotiator despite the political disagreements between them.[4]

Supreme Court of Israel

[edit]On 22 September 1978, Barak began his service as a Justice of the Supreme Court of Israel – the youngest of all of the judges. In 1982–83 he served as a member of the Kahan Commission, a state investigation committee formed to investigate the circumstances surrounding the Sabra and Shatila massacre. As part of the committee's conclusions, then Minister of Defense Ariel Sharon was removed from his position. The committee further recommended that he never be appointed to that position again in the future. In 1993, with the retirement of the Deputy President of the Supreme Court Menachem Elon, Barak was appointed the Deputy President. Subsequently, with the retirement of the President Meir Shamgar on 13 August 1995, Barak was appointed the President of the Supreme Court.

In the course of his service on the Supreme Court, Barak greatly expanded the range of issues with which the court dealt.[5] He canceled the standing test which Israel's Supreme Court had used frequently, and greatly expanded the scope of justiciability by allowing petitions on a range of matters. Professor Daphna Barak-Erez commented that:"One of the most significant impacts of Judge Barak on Israeli law is found in the change which he led with regard to all matters of justiciability. Judge Barak was the instigator and leader of the outlook which regards the traditional doctrine of justiciability as inappropriately and unnecessarily limiting the matters which the court deals with. Under the leadership of Judge Barak, the Supreme Court significantly increased the [range of] fields in which it is [willing to intervene]."[6]

Simultaneously, he advanced a number of standards, both for public administration (mainly, the standard of the reasonableness of the administrative decision) and in the private sector (the standard of good faith), while blurring the distinction between the two. Barak's critics have argued that, in doing so, the Supreme Court under his leadership harmed judicial consistency and stability, particularly in the private sector.[7]

After 1992, much of his judicial work was focused on advancing and shaping Israel's Constitutional Revolution (a phrase which he coined), which he believed was brought about by the adoption of Basic Laws in the Israeli Knesset dealing with human rights. According to Barak's approach, which was adopted by the Supreme Court, the Constitutional Revolution brought values such as the Right to Equality, Freedom of Employment and Freedom of Speech to a position of normative supremacy, and thereby granted the courts (not just the Supreme Court) the ability to strike down legislation which is inconsistent with the rights embodied in the Basic Laws. Consequently, Barak held that the State of Israel has been transformed from a parliamentary democracy to a constitutional parliamentary democracy, in that its Basic Laws were to be interpreted as its constitution.[8]

During his time as President of the Supreme Court, Barak advanced a judicial activist approach, whereby the court was not required to limit itself to judicial interpretation, but rather was permitted to fill the gaps in the law through judicial legislation at common law. This approach was highly controversial and was met with much opposition, including by some politicians. The Israeli legal commentator Ze'ev Segal wrote in a 2004 article, "Barak sees the Supreme Court as a [force for societal change], far beyond the primary role as a decisor in disputes. The Supreme Court under his leadership is fulfilling a central role in the shaping of Israeli law, not much less than [the role of] the Knesset. Barak is the leading power in the court, as a key judge in it for a quarter of a century, and as the number 1 judge for some 10 years now."

On 14 September 2006, upon reaching the mandatory age, Barak retired from the Supreme Court. Three months later he published his final judgments, among them a number of precedents regarding damages in tort for residents of the Palestinian territories, Israel's policy of targeted killing, and preferential treatment for IDF veterans.

Parallel to his service in the Supreme Court, Barak also served as the head of a committee which, for some twenty years, drafted the Israeli Civil Codex, which worked to unite the 24 main civil law statutes in Israeli law under a single comprehensive law.

Selected judgments

[edit]

- CA 6821/93 United Hamizrahi Bank Ltd. v. Migdal Kfar Shitufi 49(4) P.D 221: The judgment in which Barak, together with other judges, described the Constitutional Revolution as he understood it, which began following the legislation of Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty and Basic Law: Freedom of Occupation. In this case it was held that the Supreme Court could strike down Knesset legislation which is inconsistent with these Basic Laws.

- CA 243/83 The Jerusalem Municipality v. Gordon, 39(1) P.D 113: In this judgment Barak reformed key aspects of Israeli tort law.

- HC 3269/95 Katz v. Regional Rabbinical Court, 50(4) P.D 590: In this judgment Barak held, sitting as Deputy President to Meir Shamgar, that the laws pertaining to property disputes arising from divorce are not caused by the act of marriage and thus are not to be regarded as matters of marriage. Rather, they derive from an agreement between the parties and are an aspect of the freedom of association. This case established that the Israeli Rabbinical courts must apply the doctrine of joint matrimonial property, a doctrine based in Israeli common law rather than the Halakha (Jewish religious law).

- CA 4628/93 State of Israel v. Guardian of Housing and Initiatives (1991) Ltd., 49(2) P.D 265: In this judgment Barak proposed a new approach to contract construction, holding that a lot of weight should be given to the circumstances which led to the formation of the contract. Some aspects of Barak's views in this regard remain controversial, but his general approach to contract construction is today accepted by the Supreme Court.

- CA 165/82 Kibbutz Hatzor v Assessing Officer, 39(2) P.D 70: This judgment was a turning point in the interpretation of tax law in Israel, in establishing that a purposive approach was generally preferred to textualism in determining the meaning of the law.

- FH 40/80 Koenig v. Cohen, 36(3) P.D 701: In this judgment Barak, in the minority, expounded upon his approach to interpreting legislation. Today this approach has become an acceptable approach to statutory interpretation.

- CA 817/79, Kossoy v. Y.L. Feuchtwanger Bank Ltd., 38(3) P.D 253: In this judgment Barak imposed a duty of fairness upon one who controls a company, holding that one who controls a company cannot sell his shares of the company when as a consequence of doing so the company, and thus its shareholders, would be harmed.

South Africa v. Israel

[edit]On January 11, 2024, the Israeli government appointed Barak as an ad hoc judge to serve on the International Court of Justice case South Africa v. Israel, brought against Israel by South Africa on charges of genocide.[9] In this role, Barak voted against several of the provisional measures the ICJ imposed on Israel, such as preventing acts of genocide, protecting evidence, and facilitating humanitarian aid, suggesting he found insufficient basis in the evidence for these specific requirements.[10]

On June 5, 2024, Barak resigned from his role as an ad hoc judge, citing personal reasons.[11]

Views and opinions

[edit]Barak championed a proactive judiciary that has interpreted Israel's Basic Law as its constitution, and challenged Knesset laws on that basis. Barak's legal philosophy starts with the belief that "the world is filled with law". This idea portrays law as an all-encompassing framework of human affairs from which no action can ever be immune: Whatever the law does not prohibit, it permits; either way, the law always has its say, on everything.[12] Following his retirement from the Supreme Court, the new President of the Court, Judge Dorit Beinisch, said at his farewell ceremony: "At the heart of the development of the law of Israel stands Aharon Barak. He opened new horizons. The law as it stands after his [Presidency] differs in its purpose from the era which preceded him. Since his first year in the Supreme Court his rulings were groundbreaking, since '78 and until today he set the central legal norms that this court granted Israeli society."

On the issue of the substantial expansion of the right of standing and the test of reasonableness of an administrative decision (which grants the courts the power to overrule an administrative decision if the judge is convinced that it does not "stand [within the] bounds of reasonableness"), Amnon Rubinstein wrote:" Thus a situation has arisen whereby the Supreme Court may convene and decide on every conceivable issue. In addition to that the unreasonableness of an administrative decision will be grounds for judicial intervention. This was a total revolution in the judicial thinking which characterized the Supreme Court of previous generations, and this has given it the reputation of the most activist court in the world, causing both admiration and criticism. In practice, in many respects the Supreme Court under Barak has become an alternate government."

Barak is a secular Jew but believes in compromise with the religious sector, and state support for religion.[citation needed] His judgments on the interaction between religion and state have led to hostility towards him by some in the religious public. Religious Jews from all sectors of society (including both Haredim and Religious Zionists) held a mass protest against the Supreme Court under his presidency, after the Supreme Court ruled that in cases of divorce the Israeli religious courts of law are required to decide property disputes according to the law of the Knesset rather than according to the Halakha.[citation needed]

Criticism

[edit]Among critics of Barak's judicial activism are former President of the Supreme Court of Israel Moshe Landau, Ruth Gavison, and Richard Posner. Posner, a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit and authority on jurisprudence, criticised Barak's decision to interpret the Basic Laws as Israel's constitution, stating that "only in Israel ... do judges confer the power of abstract review on themselves, without benefit of a constitutional or legislative provision."[13] He also argues that Barak's idea of the courts enforcing a set of rights which they find in "substantive" democracy, rather than merely democratic political rights, actually involves a curtailing of democracy and results in a "hyperactive judiciary."[13] Furthermore, he claims that Barak's approach to the interpretation of statutes involves, in practice, interpretation in the context of the judge's own personal ideal system, and "opens up a vast realm for discretionary judgment", rather than providing for an objective interpretation of the statute.[13] He is also critical of Barak's view of the separation of powers, arguing that, in effect, it is that "judicial power is unlimited and the legislature cannot remove judges."[13] He also asserts that Barak fails to apply his own judicial philosophy in practice at times.[13] Nevertheless, Posner said that "Barak himself is by all accounts brilliant, as well as austere and high-minded – Israel's Cato", and that while he would not regard Barak's judicial approach as a desirable universal model, it may be suited to Israel's specific circumstances.[13] He also suggested that if there were a Nobel Prize for law, Barak would likely be among its early recipients.[13]

His judgments on matters of security have been subject to criticism by some on both the left and the right.[14][15][16][vague]

Key legal doctrines

[edit]Awards and recognition

[edit]- In 1975, Barak was awarded the Israel Prize, in jurisprudence.[18]

- In 1987, he was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[19]

- In 2003, he received Honorary Degrees from Brandeis University.

- In 2006, he received the Justice Prize of the Peter Gruber Foundation for "outstanding courage and principle who has devoted his life to the promotion of justice and the just rule of law."[20]

- In 2007, he received Honorary Degrees from Columbia University.

Published works

[edit]- Judicial Discretion (1989) ISBN 978-0-300-04099-9

- Purposive Interpretation in Law (2005) ISBN 978-0-691-12007-2 Book review.[21]

- The Judge in a Democracy (2006) ISBN 978-0-691-12017-1

- Proportionality: Constitutional Rights and Their Limitations (2012) ISBN 978-1-107-40119-8

- Human Dignity: The Constitutional Value and the Constitutional Right (2015) ISBN 978-1-107-09023-1

- Begin and the Rule of Law, Israel Studies, Indiana University Press, Volume 10, Number 3, Fall 2005, pp. 1–28

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Aharon Barak – President of the Supreme Court". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ^ Avnery, Uri (18 April 2015). "There Are Still Judges…". Gush Shalom. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ^ "Aharon Barak – Curriculum Vitae" (PDF). Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Retrieved 13 November 2024.

- ^ Carter, James Earl (2006). Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-7432-8502-5.

- ^ Neuer, Hillel (1998). "Aharon Barak's Revolution". Azure. Winter 5758 (3). Retrieved 24 January 2011.mirror Archived 1 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 29 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "השופט כבוחן כליות ולב". Makorrishon.co.il. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ פרוטוקול:208 – חוקה בהסכמה רחבה (in Hebrew). Huka.gov.il. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ Berman, Lazar; Horowitz, Michael; Sharon, Jeremy (7 January 2024). "Israel tasks ex-Supreme Court chief Aharon Barak to serve at Hague genocide hearings". Retrieved 10 January 2024.

- ^ "Separate opinion of Judge ad hoc Barak | INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE". www.icj-cij.org. Retrieved 13 November 2024.

- ^ "Aharon Barak steps down from role as ad hoc judge at ICJ for personal reasons". Times of Israel. 5 June 2024.

- ^ Aharon Barak's revolution Archived 1 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g Posner, Richard A. (23 April 2007). "Enlightened Despot". The New Republic. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ^ "ערוץ 7 - רשת תקשורת ישראלית". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 29 October 2009.

- ^ "אצלי זה פוליטי, נקודה – מוסף הארץ – הארץ". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 November 2009. Retrieved 29 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Aharon Barak on the Role of Proportionality Archived 26 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine (Foundation for Law, Justice and Society Annual Lecture 2009)

- ^ "Israel Prize Official Site – Recipients in 1975 (in Hebrew)".

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter B" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ "2006 Gruber Justice Prize Press Release". Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ^ Kahn, Ronald (September 2006). "PURPOSIVE INTERPRETATION IN LAW, by Aharon Barak". Law and Politics Book Review. 16 (9): 708–738. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010.

External links

[edit]- Aharon Barak – in the online exhibition "To Build and To Be Built" – The Contribution of Holocaust Survivors to the State of Israel – Yad Vashem

- The Judge in a Democracy (Princeton University Press, 2006)

- "The Legacy of Justice Aharon Barak: A Critical Review", by Nimer Sultany

- Review of Barak's book, Hassan Jabareen

- Justice Barak Unbound, Nathan J. Diament

- Human Rights and their Limitations: The Role of Proportionality Video of a lecture by Aharon Barak for the Foundation for Law, Justice and Society, Oxford, 2009

- 1936 births

- Chief justices of the Supreme Court of Israel

- Harvard University alumni

- Academic staff of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Israel Prize in law recipients

- Academic staff of Reichman University

- Living people

- Lithuanian Jews

- Academic staff of the University of Toronto Faculty of Law

- Yale Law School faculty

- Attorneys general of Israel

- Members of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities

- Lithuanian emigrants to Mandatory Palestine

- Israeli people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Kovno Ghetto inmates

- Israeli Jews

- Georgetown University Law Center faculty

- People from Kaunas

- Holocaust survivors