ABO (gene)

| ABO | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | ABO, A3GALNT, A3GALT1, GTB, NAGAT, ABO blood group (transferase A, alpha 1-3-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase; transferase B, alpha 1-3-galactosyltransferase), alpha 1-3-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase and alpha 1-3-galactosyltransferase | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 110300; MGI: 2135738; HomoloGene: 69306; GeneCards: ABO; OMA:ABO - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| EC number | 2.4.1.37 2.4.1.40, 2.4.1.37 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

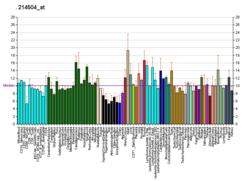

Histo-blood group ABO system transferase is an enzyme with glycosyltransferase activity, which is encoded by the ABO gene in humans.[5][6] It is ubiquitously expressed in many tissues and cell types.[7] ABO determines the ABO blood group of an individual by modifying the oligosaccharides on cell surface glycoproteins. Variations in the sequence of the protein between individuals determine the type of modification and the blood group. The ABO gene also contains one of 27 SNPs associated with increased risk of coronary artery disease.[8]

Alleles

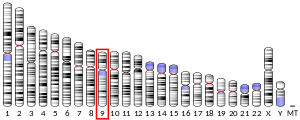

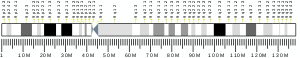

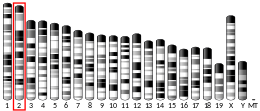

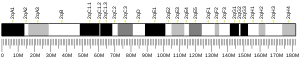

[edit]The ABO gene resides on chromosome 9 at the band 9q34.2 and contains 7 exons.[6] The ABO locus encodes three alleles, that is, 3 variants of the same gene. One allele is derived from each parent.

The A allele produces α-1,3-N-acetylgalactosamine transferase (A-transferase), which catalyzes the transfer of GalNAc residues from the UDP-GalNAc donor nucleotide to the Gal residues of the acceptor H antigen, converting the H antigen into A antigen in A and AB individuals.

The B allele encodes α-1,3-galactosyl transferase (B-transferase), which catalyzes the transfer of Gal residues from the UDP-Gal donor nucleotide to the Gal residues of the acceptor H antigen, converting the H antigen into B antigen in B and AB individuals. Remarkably, the difference between the A and B glycosyltransferase enzymes is only four amino acids.[9]

The O allele lacks both enzymatic activities because of the frameshift caused by a deletion of guanine-258 in the gene which corresponds to a region near the N-terminus of the protein.[10] This results in a frameshift and thus of a truncated protein of only 117 amino acids.[9][11] The truncated protein is unable to modify oligosaccharides which end in fucose linked to galactose. Thus no A or B antigen is found in O individuals. This sugar combination is termed the H antigen. These antigens play an important role in the match of blood transfusion and organ transplantation.[9] Other minor alleles have been found for this gene.[6]

Common alleles

[edit]There are six common alleles in individuals of European descent. Nearly every living human's phenotype for the ABO gene is some combination of just these six alleles:[12][13]

- A

- A101 (A1)

- A201 (A2)

- B

- B101 (B1)

- O

- O01 (O1)

- O02 (O1v)

- O03 (O2)

Many rare variants of these alleles have been found in human populations around the world.

Clinical significance

[edit]In human cells, the ABO alleles and their encoded glycosyltransferases have been described in several oncologic conditions.[14] Using anti-GTA/GTB monoclonal antibodies, it was demonstrated that a loss of these enzymes was correlated to malignant bladder and oral epithelia.[15][16] Furthermore, the expression of ABO blood group antigens in normal human tissues is dependent upon the type of differentiation of the epithelium. In most human carcinomas, including oral carcinoma, a significant event as part of the underlying mechanism is decreased expression of the A and B antigens.[17] Several studies have observed that a relative down-regulation of GTA and GTB occurs in oral carcinomas in association with tumor development.[17][18] More recently, a genome wide association study (GWAS) has identified variants in the ABO locus associated with susceptibility to pancreatic cancer.[19][20]

Clinical marker

[edit]A multi-locus genetic risk score study based on a combination of 27 loci, including the ABO gene, identified individuals at increased risk for both incident and recurrent coronary artery disease events, as well as an enhanced clinical benefit from statin therapy. The study was based on a community cohort study (the Malmo Diet and Cancer study) and four additional randomized controlled trials of primary prevention cohorts (JUPITER and ASCOT) and secondary prevention cohorts (CARE and PROVE IT-TIMI 22).[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c ENSG00000281879 GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000175164, ENSG00000281879 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000015787 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Ferguson-Smith MA, Aitken DA, Turleau C, de Grouchy J (September 1976). "Localisation of the human ABO: Np-1: AK-1 linkage group by regional assignment of AK-1 to 9q34". Human Genetics. 34 (1): 35–43. doi:10.1007/BF00284432. PMID 184030. S2CID 12384399.

- ^ a b c "Entrez Gene: ABO ABO blood group (transferase A, alpha 1-3-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase; transferase B, alpha 1-3-galactosyltransferase)".

- ^ "BioGPS - your Gene Portal System". biogps.org. Retrieved 2016-10-11.

- ^ a b Mega JL, Stitziel NO, Smith JG, Chasman DI, Caulfield MJ, Devlin JJ, Nordio F, Hyde CL, Cannon CP, Sacks FM, Poulter NR, Sever PS, Ridker PM, Braunwald E, Melander O, Kathiresan S, Sabatine MS (June 2015). "Genetic risk, coronary heart disease events, and the clinical benefit of statin therapy: an analysis of primary and secondary prevention trials". Lancet. 385 (9984): 2264–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61730-X. PMC 4608367. PMID 25748612.

- ^ a b c Yamamoto F, Clausen H, White T, Marken J, Hakomori S (May 1990). "Molecular genetic basis of the histo-blood group ABO system". Nature. 345 (6272): 229–33. Bibcode:1990Natur.345..229Y. doi:10.1038/345229a0. PMID 2333095. S2CID 4237562.

- ^ Iwamoto S, Kumada M, Kamesaki T, Okuda H, Kajii E, Inagaki T, Saikawa D, Takeuchi K, Ohkawara S, Takahashi R, Ueda S, Inoue S, Tahara K, Hakamata Y, Kobayashi E (November 2002). "Rat encodes the paralogous gene equivalent of the human histo-blood group ABO gene. Association with antigen expression by overexpression of human ABO transferase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (48): 46463–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M206439200. PMID 12237302.

- ^ "ABO - Histo-blood group ABO system transferase - Homo sapiens (Human) - ABO gene & protein". www.uniprot.org. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- ^ Seltsam A, Hallensleben M, Kollmann A, Blasczyk R (October 2003). "The nature of diversity and diversification at the ABO locus". Blood. 102 (8): 3035–42. doi:10.1182/blood-2003-03-0955. PMID 12829588.

- ^ Ogasawara K, Bannai M, Saitou N, Yabe R, Nakata K, Takenaka M, Fujisawa K, Uchikawa M, Ishikawa Y, Juji T, Tokunaga K (June 1996). "Extensive polymorphism of ABO blood group gene: three major lineages of the alleles for the common ABO phenotypes". Human Genetics. 97 (6): 777–83. doi:10.1007/BF02346189. PMID 8641696. S2CID 12076999.

- ^ Goldman M (February 2007). "Translational mini-review series on Toll-like receptors: Toll-like receptor ligands as novel pharmaceuticals for allergic disorders". Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 147 (2): 208–16. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03296.x. PMC 1810467. PMID 17223960.

- ^ Kay HE (November 1982). "Bone marrow transplantation: 1982". British Medical Journal. 285 (6351): 1296–8. doi:10.1136/bmj.285.6351.1296. PMC 1500229. PMID 6812684.

- ^ Hakomori S (December 1999). "Antigen structure and genetic basis of histo-blood groups A, B and O: their changes associated with human cancer". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 1473 (1): 247–66. doi:10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00183-x. PMID 10580143.

- ^ a b Dabelsteen E, Gao S (January 2005). "ABO blood-group antigens in oral cancer". Journal of Dental Research. 84 (1): 21–8. doi:10.1177/154405910508400103. PMID 15615870. S2CID 16975373.

- ^ Dabelsteen E (February 2002). "ABO blood group antigens in oral mucosa. What is new?". Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine. 31 (2): 65–70. doi:10.1046/j.0904-2512.2001.00004.x. PMID 11896825.

- ^ Amundadottir LT (2016-01-01). "Pancreatic Cancer Genetics". International Journal of Biological Sciences. 12 (3): 314–25. doi:10.7150/ijbs.15001. PMC 4753160. PMID 26929738.

- ^ Amundadottir L, Kraft P, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Fuchs CS, Petersen GM, Arslan AA, et al. (September 2009). "Genome-wide association study identifies variants in the ABO locus associated with susceptibility to pancreatic cancer". Nature Genetics. 41 (9): 986–90. doi:10.1038/ng.429. PMC 2839871. PMID 19648918.

Further reading

[edit]- Nagai M, Davè V, Kaplan BE, Yoshida A (January 1978). "Human blood group glycosyltransferases. I. Purification of n-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 253 (2): 377–9. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)38216-9. PMID 618875.

- Takeya A, Hosomi O, Shimoda N, Yazawa S (September 1992). "Biosynthesis of the blood group P antigen-like GalNAc beta 1-->3Gal beta 1-->4GlcNAc/Glc structure: a novel N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase in human blood plasma". Journal of Biochemistry. 112 (3): 389–95. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123910. PMID 1429528.

- Kominato Y, McNeill PD, Yamamoto M, Russell M, Hakomori S, Yamamoto F (November 1992). "Animal histo-blood group ABO genes". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 189 (1): 154–64. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(92)91538-2. PMID 1449469.

- Yamamoto F, McNeill PD, Hakomori S (August 1992). "Human histo-blood group A2 transferase coded by A2 allele, one of the A subtypes, is characterized by a single base deletion in the coding sequence, which results in an additional domain at the carboxyl terminal". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 187 (1): 366–74. doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(05)81502-5. PMID 1520322.

- Clausen H, White T, Takio K, Titani K, Stroud M, Holmes E, Karkov J, Thim L, Hakomori S (January 1990). "Isolation to homogeneity and partial characterization of a histo-blood group A defined Fuc alpha 1----2Gal alpha 1----3-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase from human lung tissue". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 265 (2): 1139–45. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)40169-5. PMID 2104827.

- Yamamoto F, Marken J, Tsuji T, White T, Clausen H, Hakomori S (January 1990). "Cloning and characterization of DNA complementary to human UDP-GalNAc: Fuc alpha 1----2Gal alpha 1----3GalNAc transferase (histo-blood group A transferase) mRNA". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 265 (2): 1146–51. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)40170-1. PMID 2104828.

- Yamamoto F, Hakomori S (November 1990). "Sugar-nucleotide donor specificity of histo-blood group A and B transferases is based on amino acid substitutions". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 265 (31): 19257–62. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)30652-X. PMID 2121736.

- Whitehead JS, Bella S, Kim YS (June 1974). "An N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase from human blood group A plasma. II. Kinetic and physicochemical properties". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 249 (11): 3448–52. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)42593-3. PMID 4831223.

- Whitehead JS, Bella A, Kim YS (June 1974). "An N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase from human blood group A plasma. I. Purification and agarose binding properties". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 249 (11): 442–7. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)42592-1. PMID 4831233.

- Kobata A, Ginsburg V (March 1970). "Uridine diphosphate-N-acetyl-D-galactosamine: D-galactose alpha-3-N-acetyl-D-galactosaminyltransferase, a product of the gene that determines blood type A in man". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 245 (6): 1484–90. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)63261-2. PMID 5442829.

- Yoshida A, Yamaguchi H, Okubo Y (May 1980). "Genetic mechanism of cis-AB inheritance. I. A case associated with unequal chromosomal crossing over". American Journal of Human Genetics. 32 (3): 332–8. PMC 1686052. PMID 6770676.

- Olsson ML, Thuresson B, Chester MA (November 1995). "An Ael allele-specific nucleotide insertion at the blood group ABO locus and its detection using a sequence-specific polymerase chain reaction". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 216 (2): 642–7. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1995.2670. PMID 7488159.

- Bennett EP, Steffensen R, Clausen H, Weghuis DO, van Kessel AG (January 1995). "Genomic cloning of the human histo-blood group ABO locus". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 206 (1): 318–25. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1995.1044. hdl:2066/22100. PMID 7598760. S2CID 39351683.

- Yamamoto F, McNeill PD, Hakomori S (February 1995). "Genomic organization of human histo-blood group ABO genes". Glycobiology. 5 (1): 51–8. doi:10.1093/glycob/5.1.51. PMID 7772867.

- Bennett EP, Steffensen R, Clausen H, Weghuis DO, Geurts van Kessel A (June 1995). "Genomic cloning of the human histo-blood group ABO locus". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 211 (1): 347. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1995.1817. hdl:2066/22100. PMID 7779106.

- Yamamoto F, McNeill PD, Kominato Y, Yamamoto M, Hakomori S, Ishimoto S, Nishida S, Shima M, Fujimura Y (1993). "Molecular genetic analysis of the ABO blood group system: 2. cis-AB alleles". Vox Sanguinis. 64 (2): 120–3. doi:10.1111/j.1423-0410.1993.tb02529.x. PMID 8456556. S2CID 23119465.

- Yamamoto F, McNeill PD, Yamamoto M, Hakomori S, Harris T (1993). "Molecular genetic analysis of the ABO blood group system: 3. A(X) and B(A) alleles". Vox Sanguinis. 64 (3): 171–4. doi:10.1111/j.1423-0410.1993.tb05157.x. hdl:2027.42/71979. PMID 8484250. S2CID 43662514.

- Ogasawara K, Yabe R, Uchikawa M, Saitou N, Bannai M, Nakata K, Takenaka M, Fujisawa K, Ishikawa Y, Juji T, Tokunaga K (October 1996). "Molecular genetic analysis of variant phenotypes of the ABO blood group system". Blood. 88 (7): 2732–7. doi:10.1182/blood.V88.7.2732.bloodjournal8872732. PMID 8839869.

External links

[edit]- Human ABO genome location and ABO gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P16442 (Histo-blood group ABO system transferase) at the PDBe-KB.

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.