9th Operations Group

9th Operations Group

| |

|---|---|

U-2 Dragon Lady 80-1080 from the 9th Reconnaissance Wing | |

| Active | 1922–1948; 1949–1952; 1991–present |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Role | Reconnaissance |

| Part of | Air Combat Command 9th Reconnaissance Wing |

| Motto(s) | Semper Paratus Latin Always Ready[1] |

| Engagements | World War IIAmerican Theater (1941–1943) Asiatic-Pacific Theater |

| Decorations | Distinguished Unit Citation Air Force Meritorious Unit Award Air Force Outstanding Unit Award[2] |

| Insignia | |

| 9th Operations Gp emblem[note 1][note 2] |  |

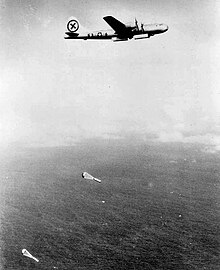

| WW II Tail Marking | Circle K |

The 9th Operations Group is the operational flying component of the 9th Reconnaissance Wing, stationed at Beale Air Force Base, California.

The 9th OG's mission is to organize, train and equip Lockheed U-2R, RQ-4 Global Hawk and MC-12W Liberty combat elements for peacetime intelligence gathering, contingency operations, conventional war fighting and Emergency War Order support.

It is a descendant organization of the 9th Group (Observation), one of the 15 original combat air groups formed by the Army before World War II. It is the fourth oldest active group in the USAF, and the seventh created following the establishment of the U.S. Air Service. During World War II, the 9th Bombardment Group, Very Heavy was a B-29 Superfortress group assigned to Twentieth Air Force flying bombardment operations against Japan. Its aircraft were identified by a "X" inside a Circle painted on the tail.

History

[edit]- For related history and lineage, see 9th Reconnaissance Wing

Origins

[edit]The 1st Squadron was the first squadron organized in the air force, formed on 5 March 1913, at Texas City, Texas, as the 1st Aero Squadron. In March 1916, the 1st Aero Squadron, with Captain Benjamin D. Foulois as commander, supported General "Black Jack" Pershing's punitive expeditions into Mexico. Pancho Villa had raided Columbus, New Mexico, and Pershing pursued and hoped to capture him. On 16 March 1916, Captain T.F. Dodd, with Captain Foulois as observer, flew the first American aerial reconnaissance mission in combat. The wavy line in the middle of the wing's emblem represents the Rio Grande and the 1st Aero Squadron's operations in 1916. The 5th Aero Squadron was organized in 1917 at Kelly Field, Texas, and served as a flying training unit.

World War I

[edit]Between 12 and 15 September 1918, they joined the great air armada of 1,481 airplanes in a massive air offensive in the St. Mihiel sector of France. The squadrons also participated in the Champagne-Marne, Aisne-Marne, and Meuse-Argonne combat operations. The four black crosses on the wing's emblem commemorate these air battles.

Between the wars

[edit]

From June to September 1921 both squadrons served as part of the 1st Provisional Air Brigade, organized by Brig. Gen. William L. Mitchell to demonstrate aerial bombardment of battleships.

Originally created as the 9th Observation Group on 19 July 1922, as part of the U.S. Army Air Service, the group was organized on 1 August 1922, at Mitchel Field, New York.[3] The squadrons assigned to the group were the 1st and 5th Aero Squadrons (Observation), both re-designated bomb squadrons in March 1935. From 1923 to 1929, both squadrons of the 9th were reassigned to higher echelons, but remained in actuality a part of the group. From 1922 to 1940, they also trained, took part in maneuvers, and participated in air shows. The 99th Observation Squadron, organized at Kelly Field in 1917 and earning four campaign streamers in France, was added to the 9th Group on 9 November 1928, and on 15 February 1929, all three squadrons were assigned permanently. The 9th Observation Group used the Airco DH.4 for its observation airplane between 1922 and 1928, and the Curtiss O-1B Falcon from 1928 to 1935.

The Air Service became the U.S. Army Air Corps on 2 July 1926.

The 9th was re designated the ‘’'9th Bombardment Group'’’ in 1935, and early that year, the Air Corps re-organized, with all combat groups within the continental United States being centrally controlled for the first time, under a new command organization called General Headquarters Air Force. The role of observation as the primary function of the air arm had been de-emphasized in the creation of eight new groups between 1927 and 1932. With the creation of GHQAF it was further de-emphasized and the 9th was converted into a bombardment group. Made a part of the 2nd Wing, the 9th BG was responsible for the air defense of the East Coast of the United States.

The group's designation was changed to the 9th Bombardment Group on 19 February 1935, the 9th Bombardment Group (Medium) on 6 December 1939, and the 9th Bombardment Group (Heavy) on 20 November 1940. During the period 1935–1940 the 9th Bombardment Group trained aircrews, took part in maneuvers, and participated in air shows, equipped with Keystone B-6 (1935–36), Martin B-10 (1936–38), and the B-18 Bolo (1938–1942).

The 9th moved to Rio Hato Airport, Panama, on 12 November 1940, to serve as part of the defense force for the Panama Canal. The 44th Reconnaissance Squadron stationed at Albrook Field, Panama Canal Zone, was attached to the 9th on 20 November 1940. In addition to 5 additional B-18's it provided a single B-17B Flying Fortress to the group. The group later hunted German U-boats in the Caribbean.

The 9th Bombardment Group relocated in a series of moves to Caribbean bases to conduct antisubmarine patrols. The 1st Bomb Squadron moved to Piarco Airport, Trinidad, on 24 April 1941; followed by the 5th Bomb Squadron to Beane Field, Saint Lucia, on 28 September; the group headquarters squadron to Waller Field, Trinidad, on 30 October (where it was joined by the 1st Bomb Squadron); the 44th Reconnaissance Squadron to Atkinson Field, British Guiana, on 4 November; and the 99th Bomb Squadron to Zandrey Field, Surinam, on 3 December 1941.

World War II

[edit]Anti-Submarine Patrols

[edit]The 44th Reconnaissance Squadron was assigned to the 9th Bombardment Group on 25 February 1942, and re designated the 430th Bombardment Squadron on 22 April. The group's Headquarters Squadron was disbanded on 22 July 1942. The 1st Bomb Squadron changed stations to Edinburg Field, Trinidad, on 23 August, and the group was assigned to the Antilles Air Task Force on 18 September, where it continued antisubmarine patrols and conducted reconnaissance of the Vichy French fleet at Martinique, using B-18 aircraft from a base in Trinidad. It then returned without personnel or equipment to the United States on 31 October 1942.

Army Air Force School of Applied Tactics

[edit]The 9th Bombardment Group's assets were transferred to the 25th Bombardment Group and it was returned without personnel or equipment to the US in October 1942, where it was reconstituted as part of the Army Air Force School of Applied Tactics at Orlando Army Air Base, Florida. The group's squadrons were assigned as school squadrons, with the 1st located at Brooksville Army Air Field, the 5th at Pinecastle Army Air Field, and the 99th at Montbrook Army Air Field, Florida. These used B-17 Flying Fortress, B-24 Liberator, and B-26 Marauder aircraft to train cadres for 44 bomb groups in organization and operations, performed bombing pattern tests, experimented with 3-plane formations to attack moving ships, and performed over a hundred equipment tests.

B-29 Superfortress

[edit]

On 3 March 1944, the ‘’'9th Bombardment Group'’’ was established on paper at Dalhart Army Air Field, Texas, as part of the 313th Bombardment Wing, to organize and train for B-29 operations in the Western Pacific. The 9th helped to develop operational bombardment tactics and tested special devices and equipment during this time.

During April, the key personnel of the new group (including group commander Col. Donald Eisenhart and Deputy Group Commander Lt.Col. Henry Huglin) assembled at Dalhart, forming the command and operations cadres, and were transferred with the group to McCook Army Airfield, Nebraska. After a brief period establishing the units at McCook, the cadre of group and squadron operations staffs went by train to the Army Air Force School of Applied Tactics in Orlando, Florida. This occurred during May for the 4-week training course in organizing and conducting combat operations with very heavy bomb group units.

While the cadre was training in Florida, an influx of new personnel continued at McCook.

After the return of the group and squadron cadres in June 1944, the squadrons organized new combat crews and the group conducted an intensive program of ground and flying training using B-17 aircraft to practice takeoffs, landings, instrument and night flying, cross-country navigation, high altitude formation flying, and bombing and gunnery practice.

The 9th Group had been forced to use B-17's in its training because the development of the B-29 as an operational weapon had been plagued since an early flight test on 28 December 1942, resulted in an engine fire. This culminated in a massive emergency modification program in the winter of 1943–44 ordered by Chief of the U.S. Army Air Forces, General Henry H. Arnold, and nicknamed the "Battle of Kansas". In particular the program sought to resolve a spate of problems with serious engine fires and faulty gunnery central fire control systems. All B-29s modified in this program were diverted to the 58th Bombardment Wing to meet President Franklin D. Roosevelt's commitment to China to have B-29's deployed to the China Burma India Theater in the spring of 1944. This commitment inadvertently led to there being no available aircraft to equip the 12 new groups being formed in the 73rd, 313th, and 314th Bombardment Wings.

Pacific Theater

[edit]

The 9th Group received its first training B-29 on 13 July 1944. After four further months of training, Col. Eisenhart declared the unit ready for movement overseas, and its ground echelon left McCook for the Seattle, Washington, port of embarkation on 18 November 1944, traveling by the troopship U.S.S. Cape Henlopen to the Mariana Islands on a voyage that required thirty days. The ground echelon of the group debarked at Tinian on 28 December and was assigned a camp on the west side of the island between the two airfields.

The air echelon of the 9th Bombardment Group began its overseas movement in January 1945 by sending the combat crews to Herington Field, Kansas, where over a three-week period they accepted 37 new B-29s. The first bombers left their staging field at Mather Army Airfield, California on 15 January 1945, and proceeded individually by way of Hickam Field, Hawaii, and Kwajalein to North Field, Tinian, with the first five arriving on 18 January 1945. The last of the original 37 airplanes to reach Tinian arrived on 12 February, by which time the group had already flown its first combat mission.

The 9th Bombardment Group was one of four groups of the 313th Bombardment Wing stationed at North Field as part of XXI Bomber Command, Twentieth Air Force. It was assigned the Unit identification aircraft markings of the letter "X" above a small black triangle symbol, both placed above the aircraft's tail fin serial and victor number (a one- or two-digit number assigned an airplane to identify it individually both within the group and squadron). The group carried this marking until April, when the 313th Wing changed its marking to that of a 126-inch-diameter (3.2 m) circle in black to outline a 63-inch-high (1.6 m) group letter.

The 9th Bombardment Group conducted four training missions against the Japanese-held Maug Islands in the Northern Marianas on 27, 29, 31 January, and 6 February. Its first combat mission took place on 9 February 1945 with 30 aircraft bombing a Japanese naval airfield located on the island of Moen at Truk atoll (now known as the Chuuk Islands). Flown by day at an altitude of 25,000 feet, it was in actuality a further training mission, encountering no opposition.

The second group mission was a pre-invasion bombing of Iwo Jima on 12 February, one week prior to D-Day for Operation Detachment. The capture of Iwo Jima had as its objective an emergency landing field for Twentieth Air Force bombers attacking Japan and a base for P-51D Mustang and P-47N Thunderbolt fighters to fly escort and strafing missions.

The first mission to the Japanese home islands was the 9th Bombardment Group's fifth mission overall. It was flown on 25 February 1945. Again, a day mission flown at high altitude, the target was the port facilities of Tokyo. That same day Col. Eisenhart was made Operations Officer of the 339th Bombardment Wing and was succeeded in command of the group by Lt. Col. Huglin.

Unlike their counterparts in the Eighth Air Force and Fifteenth Air Forces, B-29s of the Twentieth Air Force did not assemble in defensive formations over friendly territory before proceeding on the mission. On daytime missions to Japan (which because of the seven- to eight-hour flight time to Japan from the Marianas usually resulted in night takeoffs) B-29's took off from Tinian's multiple runways to shorten group launch times.

To conserve fuel and engine stress when the aircraft were at their heaviest, the bombers flew individually at low altitude, usually climbing to bombing altitude only in the last hour before rendezvous (dictated by weather conditions encountered). After 9 March bombing altitudes rarely exceeded 20,000 feet, reducing the amount of climb required to assemble and further conserving fuel and engine life. Flight profiles were carefully calculated during mission planning and recorded as detailed performance tables, specifying power settings and fuel consumption rates, and carried by the flight deck crews during the mission.

At a designated rendezvous point off the coast of Japan, lead B-29's (using colored-smoke generators to identify themselves) flew circles with a radius of a mile or more, at different altitudes and in different directions for squadrons within a group. Aircraft formed on the leader as they arrived, and it was not uncommon for formations to include aircraft from other groups that had been unable to locate their own group formation. If the mission plan called for a wing assembly, the lead group flew to a second assembly point and flew one large circle, measured in minutes and not distance, to allow following groups to join up. The formation stayed together only in the target area, breaking up again and reducing altitude to return to base (or Iwo Jima) individually.

Night missions had similar profiles to and from the target, except that aircraft did not assemble in the target area but bombed individually, guided by their own navigation systems and by the glow of fires started by pathfinder aircraft. In addition, bombing altitudes were rarely higher than 8,000 feet.

On the group's seventh mission, which lasted from 9 to 10 March 1945, XXI Bomber Command radically changed tactics at the direction of its commander, Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay, attacking Tokyo's urban center by night with incendiary bombs and at altitudes of only 6,400 to 7,800 feet, resulting in one of the most destructive attacks in history. The mission resulted in the first two losses to the group when B-29s from both the 1st Bomb Squadron and 99th Bomb Squadrons were forced to crash-land at sea after they ran out of fuel while returning to Tinian. The crew of the 1st BS B-29 was rescued, but three members of the 99th BS crew were killed, including the Group Radar Officer.

The Tokyo fire raid was the first of five flown between 9 and 18 March, resulting in devastation of four urban areas (Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka, and Kobe) and extensive civilian loss of life. The 9th Bombardment Group had its first bomber shot down on 16 March Kobe mission, and its second on 24 March 1945, attacking the Mitsubishi Aircraft factory at Nagoya (ironically the same crew that had ditched on 10 March).

On 27 March, the 9th Bombardment Group began a week of night missions sowing both acoustic and magnetic aerial anti-shipping mines in Japanese harbor approaches and Inland Sea ship passages, with a mission to block the Shimonoseki Straits. Attacks in April were a combination of night and medium altitude day missions against the Japanese aircraft industry, and beginning 18 April, three weeks of daytime attacks against Japanese airfields on Kyūshū launching Kamikaze attacks against U.S. naval forces at Okinawa.

The 9th Bombardment Group was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation for the mission of 15–16 April 1945, during which the 313th Bombardment Group flew B-29s for 1,500 miles at a low-level to avoid detection, over water, at night, to attack the heavily defended industrial area of Kawasaki, Japan. The group also attacked Kawasaki Heavy Industries at Kawasaki, Japan, a target judged to be "an important link in the component productive capacity...upon which industries in Tokyo and Yokahama depended."[citation needed]

Because of its strategic location between two heavily defended areas, the objective was strongly guarded by masses of defenses both on the flanks and in the immediate target area, making the approach, the bomb run, and the break-away from the target extremely hazardous." The 9th Group, dispatching 33 aircraft on a "maximum effort", was the last group over the target. Japanese anti-aircraft defenses had by then determined the bombing altitude and direction of attack, and the 9th Bombardment Group experienced close coordination between Japanese searchlights and anti-aircraft guns while over land, and accurate fire from flak boats on ingress and egress to the target area. 56 Japanese fighters were reported by returning crews, including a number of Kamikaze planes, with 2 claimed as shot down. Enemy searchlight, anti-aircraft guns, and flak boats destroyed four of the group's 33 bombers and damaged six others. Nevertheless, the attack demolished Kawasaki's strategic industrial district. The group earned a Distinguished Unit Emblem (DUE) for its actions.

On 18 May 1945, the 9th Bombardment Group resumed mine-laying operations, which continued through 28 May, for which the group was awarded its second Distinguished Unit Citation. Flying at night at 5,500 feet in what the citation stated was "the second most heavily-defended zone in Japan", the group sowed 1425 mines in 209 sorties with a 92% accuracy rate, primarily against Shimonoseki Straits and harbors on Kyūshū and the northwest coast of Honshū. This caused the 9th to win another DUE the following month that and the blocking of Inland Sea traffic as well as the isolation of important Japanese ports. During the mining campaign the 9th lost one B-29 on a takeoff accident on 20 May and a second in combat on 28 May.

On 1 June 9 Bombardment Group resumed a grim campaign of night incendiary raids against the remaining urban areas of Japan not previously attacked that continued to its final mission, 14 August 1945.

The 9th Bombardment Group flew 71 combat missions, three show-of-force flyover missions after the cessation of hostilities, and one mission to drop medical and food supplies to liberated prisoners-of-war. Total combat sorties for the group were 2,012, of which 1,843 were against the Japanese home islands. The group logged approximately 28,000 total hours of combat flight time and dropped approximately 12,000 tons of bombs and mines.

Of the 71 combat missions, 27 were incendiary raids, 14 mining operations (with 328 total sorties), 13 against airfields, 9 against aircraft production, and 9 against other industry or targets other than the home islands. 39 of the missions were flown at night, and 32 by day. Only six of the 71 combat missions were flown above 20,000 feet altitude.

The group began combat operations with 37 aircraft and ended them with 48 B-29's, with an average of 47 on hand and 33 in commission at any one time. 78 B-29's were assigned to the group at some point while it was stationed on Tinian, of which 5 were transferred to other groups. Of the remainder, 11 were shot down in combat or lost on return because of battle damage (a combat attrition rate of 16%), 2 were lost after running out of fuel, 1 crashed on takeoff, 1 crashed attempting to land, 4 were written off as salvage, and 3 were declared "war-weary" and retired from combat operations while being carried on the group inventory.

| 9th BG losses | |

|---|---|

| 11 | B-29's lost in combat |

| 4 | B-29's lost in accidents |

| 25 | Air crew killed in action |

| 21 | Air crew wounded in action |

| 84 | Air crew missing in action |

| 12 | Air crew captured |

91 combat crews of eleven crewmembers each served with the 9th Bombardment Group on Tinian. 11 combat crews were lost (13%) on combat missions while 10 crews completed a full 35-mission tour by the end of hostilities (although 12 additional crews had accumulated 31 or more missions by 15 August 1945).

The 9th Bombardment Group (VH) had 153 total aircrew casualties:

- 111 killed or presumed dead

- 25 killed in action

- 1 killed in a training accident at McCook Army Air Field

- 1 killed in an airfield accident on Tinian

- 84 missing-in-action and declared dead

- 30 wounded or injured

- 21 wounded-in-action

- 12 prisoners-of-war later repatriated

The history of the group reports that part or all of 4 crews captured after parachuting over Japan were killed in a fire in Tokyo on 25 May 1945, when prison guards intentionally kept them confined for which the guards were later prosecuted for war crimes.

Post/Cold War

[edit]Although partially demobilized with personnel and aircraft, the 9th returned to the United States, and moved to Clark Field in the Philippines on 15 April 1946. It relocated to Harmon Field on Guam on 9 June 1947, by which time it was largely a paper organization with few personnel or aircraft. The group was inactivated on Guam on 20 October 1948, and its squadrons reassigned to other units.

On 1 May 1949 the 9th Strategic Reconnaissance Group and the 1st, 5th, and 99th Strategic Reconnaissance Squadrons were re-activated at Fairfield-Suisun Air Force Base, California. Upon activation, the group was assigned to the new 9th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing under the wing base organization.

The 9th's mission was to obtain complete data through visual, photographic, electronic, and weather reconnaissance operations. To carry out this mission, the group flew RB-29 Superfortresses and a few RB-36 Peacemakers. The 9th Reconnaissance Technical Squadron also joined the 9th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing on 1 May 1949.

On 1 April 1950, the Air Force redesignated the 9th SRW as the 9th Bombardment Wing, Heavy, with similar redesignations of the 9th Group and the 1st, 5th, and 99th Squadrons. Seven months later, on 2 November, the wing and subordinate units were again re-designated to Bombardment, Medium with the transfer of the RB-36s, leaving the wing at B-29 Superfortress unit. In early February 1951, the Air Force realigned its flying operation and placed the flying squadrons directly under control of the wings. The Air Force, therefore, placed the 9th Bombardment Group in Records Unit status as part of the tri-deputate reorganization, then inactivated the group on 16 June 1952.

From 1991

[edit]Reactivated as the 9th Operations Group on 1 September 1991 as part of the Objective Wing organization of the 9th Wing.

U-2s surveyed earthquake damage over California's Yucca Valley, in June and July 1992, and Northridge in 1994. The reconnaissance photographs helped geologists map surface ruptures, fault lines, and potential landslide sites. The pictures also pinpointed infrastructure damage and allowed local and national planners to assess the relief and recovery needs.

In the early 1990s personnel and aircraft provided reconnaissance coverage during the crises in Croatia and Bosnia-Hercegovina. Later, U-2s verified compliance with the Dayton Peace Accords that ended the immediate crisis. Then, when Serbia began the "ethnic cleansing" of Albanians in Kosovo, Operation Allied Force halted the killing and restored order. During Operation Allied Force, U-2s provided over 80% of the targeting intelligence for NATO forces. NATO leadership credited the U-2 with the destruction of 39 surface-to-air missile sites and 28 aircraft of the Serbian military.

During U.S. military operations in Afghanistan in late 2001 and Iraq in early 2003, the group also flew the unmanned RQ-4 Global Hawk aircraft. Serves as the sole manager for U-2 high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft.

Lineage

[edit]- Established as the 9th Group (Observation) on 19 July 1922

- Organized on 1 August 1922

- Redesignated 9th Observation Group on 25 January 1923

- Redesignated 9th Bombardment Group on 1 March 1935

- Redesignated 9th Bombardment Group (Medium) on 6 December 1939

- Redesignated 9th Bombardment Group (Heavy) on 20 November 1940

- Redesignated 9th Bombardment Group, Very Heavy on 28 March 1944

- Inactivated on 20 October 1948

- Redesignated 9th Strategic Reconnaissance Group and activated on 1 May 1949

- Redesignated 9th Bombardment Group, Heavy on 1 April 1950

- Redesignated 9th Bombardment Group, Medium on 2 October 1950

- Inactivated on 16 June 1952

- Redesignated 9th Strategic Reconnaissance Group on 31 July 1985 (Remained inactive)

- Redesignated 9th Operations Group on 29 August 1991

- Activated on 1 September 1991[2]

Assignments

[edit]- Second Corps Area, 1 August 1922

- 19th Composite Wing, 1 April 1931

- Second Corps Area, c. 25 January 1933

- 2d Wing, 1 March 1935

- 19th Bombardment Wing, 12 November 1940

- VI Bomber Command, 25 October 1941 (attached to VI Interceptor Command (later VI Fighter Command), 28 January 1942-unknown 1942

- Army Air Forces School of Applied Tactics (later Army Air Forces Tactical Center), 31 October 1942

- Second Air Force, 9 March 1944 (attached to 17th Bombardment Operational Training Wing), 19 May–18 November 1944

- 313th Bombardment Wing, c. 28 December 1944

- Twentieth Air Force, 9 June 1947 – 20 October 1948

- 9th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing (later 9th Bombardment Wing), 1 May 1949 – 16 June 1952

- 9th Wing (later 9th Reconnaissance Wing), 1 September 1991 – present[2]

Components

[edit]- 1st Squadron (later 1st Observation Squadron, 1st Bombardment Squadron, 1st Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron, 1st Bombardment Squadron, 1st Reconnaissance Squadron): assigned 1 August 1922 – 24 March 1923, attached 24 March 1923 – 15 February 1929, assigned 15 February 1929 – 10 October 1948 (not operational, 15 March – 30 April 1946, and April 1947 – 10 October 1948); 1 June 1949 – 16 June 1952 (attached to 9th Bombardment Wing after 10 February 1951); 1 September 1991 – present[2]

- 5th Squadron (later 5th Observation Squadron, 5th Bombardment Squadron, 5th Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron, 5th Bombardment Squadron, 5th Reconnaissance Squadron): assigned 1 August 1922 – 24 March 1923, attached 24 March 1923 – 15 February 1929, assigned 15 February 1929 – 20 October 1948 (not operational 16 May-c. 16 September 1946 and April 1947 – 10 October 1948), 1 May 1949 – 16 June 1952 (attached to 9th Bombardment Wing after 10 February 1951); assigned 1 October 1994 – present[2]

- 9th Air Refueling Squadron: 1 August 1951 – 16 June 1952 (attached to 43d Bombardment Wing until 3 September 1951, 36th Air Division until 14 January 1952, 303d Bombardment Wing)[2][4]

- 12th Reconnaissance Squadron: 8 November 2001 – present[2]

- 14th Bombardment Squadron: attached 1 March 1935 – c. 8 May 1936[2]

- 18th Reconnaissance Squadron: attached 1 September 1936 – c. September 1940, assigned 3 April 2006 – 24 August 2007[2]

- 44th Reconnaissance Squadron (later 430th Bombardment Squadron): attached 20 November 1940, assigned 25 February 1942 – 10 May 1944 (not operational November 1942 – March 1943)

- 59th Bombardment Squadron: attached 6 January 1941 – 21 July 1942[2]

- 99th Observation Squadron (later 99th Bombardment Squadron, 99th Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron, 99th Bombardment Squadron, 99th Reconnaissance Squadron): attached 9 November 1928, assigned 15 February 1929 – 20 October 1948 (not operational November 1942 – February 1943, c. 15 March – 27 September 1946, and April 1947-20 October 1948), 1 May 1949 – 16 June 1952 (not operational 1–31 May 1949; (attached to 19th Bombardment Group 5 August – 23 September 1950 and 9th Bombardment Wing after 10 February 1951), 1 September 1991 – present[2]

- 349th Air Refueling Squadron: 1 September 1991 – 1 June 1992[2]

- 350th Air Refueling Squadron: 1 September 1991 – 1 October 1993[2]

- 427th Reconnaissance Squadron: 1 May 2012 – c. 20 November 2015[5][6]

- 489th Reconnaissance Squadron: 26 August 2011 – 10 May 2015[7]

Stations

[edit]- Mitchel Field, New York, 1 August 1922 – 6 November 1940

- Rio Hato Airport, Panama, 12 November 1940

- Waller Field, Trinidad, 30 October 1941 – 31 October 1942

- Orlando Army Air Base, Florida, 31 October 1942

- Dalhart Army Air Field, Texas, 9 March 1944

- McCook Army Air Field, Nebraska, 19 May – 18 November 1944

- North Field, Tinian, 28 December 1944

- Clark Field, Philippines, 15 April 1946

- Harmon Field, Guam, 9 June 1947 – 20 October 1948

- Fairfield-Suisun Air Force Base (later Travis Air Force Base), California, 1 May 1949 – 16 June 1952

- Beale Air Force Base, California, 1 September 1991 – present[2]

Aircraft

[edit]- Flew O-1, O-11, O-13, O-25, O-31, O-38, O-39, O-40, O-43, YO-31, YO-35, YO-40, OA-2, A-3, B-6, C-8,1922–1936

- Martin B-10, 1936–1938

- B-18 Bolo, 1938–1942

- B-17 Flying Fortress, 1942–1944

- RB-17 Flying Fortress (Reconnaissance), 1949–1950

- B-24 Liberator, 1942–1944

- B-25 Mitchell, 1943–1944

- B-26 Marauder, 1943–1944

- Boeing C-73, 1943–1944

- B-29 Superfortress, 1944–1947; 1949–1951

- RB-29 Superfortress (Reconnaissance), 1949–1950

- B-36 Peacemaker, 1949–1950

- KC-135 Stratotanker, 1991–1993

- Lockheed U-2, 1991–present

- T-38 Talon, 1991–present

- TR-1, 1991–1993

- SR-71 Blackbird, 1995–1999

- RQ-4 Global Hawk, 2002–present

- MC-12W, 2011–2015

Honors and campaigns

[edit]Honors

[edit]- Distinguished Unit Citation

- Kawasaki, Japan, 15–16 April 1945

- Japan, 13–28 May 1945

Campaigns

[edit]- American Theater

- Antisubmarine, American Theater

- Air Combat, Asiatic-Pacific Theater

- Air Offensive, Japan

- Western Pacific

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ The group uses the 9th Reconnaissance Wing emblem with the group designation on the scroll.

- ^ The emblem was approved for the 9th Observation Group on 20 March 1924, and in modified form for the 9th Reconnaissance Wing on 1 July 1952. The shield, in black and green, represents the old colors of the Air Service parted by a wavy line representing the Rio Grande and the 1st Aero Squadron's operations in 1916. On the gold band are four black crosses representing four World War I offensives, Aisne-Marne, Champagne-Marne, Meuse-Argonne, and St. Mihiel, in which squadrons later assigned to the 9th Group fought. The former crest of a rattlesanke coiled around a cactus recalls the service in Mexico of the 1st Aero Squadron.

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Maurer, Combat Units, pp. 49–50

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Robertson, Patsy (22 January 2017). "Factsheet 9 Operations Group (ACC)". Air Force Historical Research Agency. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ^ Conaway, William. "9th Bombardment Group (Heavy)". VI Bomber Command in Defense of the Panama Canal 1941 – 45.

- ^ Kane, Robert B. (10 June 2010). "Factsheet 9 Air Refueling Squadron (AMC)". Air Force Historical Research Agency. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ^ Robertson, Patsy (27 July 2012). "Factsheet 427 Reconnaissance Squadron (ACC)". Air Force Historical Research Agency. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ^ Guthrie, Capt Christine (20 November 2015). "Historic squadron inactivates". 9th Wing Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ^ Bailey, Carl E. (7 February 2017). "Factsheet 489 Attack Squadron (ACC)". Air Force Historical Research Agency. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

Bibliography

[edit]![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency

This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency

- Conaway, William. "VI Bomber Command In Defense Of The Panama Canal 1941 – 45". Planes and Pilots of World War Two.

- Maurer, Maurer, ed. (1983) [1961]. Air Force Combat Units of World War II (PDF) (reprint ed.). Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-912799-02-1. LCCN 61060979. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- Maurer, Maurer, ed. (1982) [1969]. Combat Squadrons of the Air Force, World War II (PDF) (reprint ed.). Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-405-12194-6. LCCN 70605402. OCLC 72556. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- Ravenstein, Charles A. (1984). Air Force Combat Wings, Lineage & Honors Histories 1947-1977. Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-912799-12-9. Retrieved 17 December 2016.