MEAI

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | none |

| Other names | 5-MeO-AI; 5-MeO-2-AI; 5-Methoxy-2-aminoindane; 5-Methoxy-2-aminoindan; Chaperon; CMND-100; CMND100 |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | High[citation needed] |

| Metabolism | Acetyl-aminoindandane[citation needed] |

| Elimination half-life | Non-linear[citation needed] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

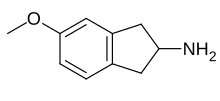

| Formula | C10H13NO |

| Molar mass | 163.220 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

MEAI, also known as 5-methoxy-2-aminoindane (5-MeO-AI), is a monoamine releasing agent of the 2-aminoindane group.[1] It specifically acts as a selective serotonin releasing agent (SSRA).[1] The drug is under development for the treatment of alcoholism, cocaine use disorder, metabolic syndrome, and obesity under the developmental code name CMND-100.[2]

Effects

[edit]When used recreationally, MEAI is reported to produce mild psychoactive effects and euphoria.[1]

Pharmacology

[edit]MEAI is a monoamine releasing agent.[1] It is a modestly selective serotonin releasing agent, with 6-fold preference for induction of serotonin release over norepinephrine release and 20-fold preference for induction of serotonin release over dopamine release.[1] In addition to inducing monoamine neurotransmitter release, MEAI has moderate affinity for the α2-adrenergic receptor.[1] Based on these findings, MEAI might produce MDMA-like entactogenic and sympathomimetic effects but may be expected to have reduced misuse liability in comparison.[1]

History

[edit]MEAI appears to have been first synthesized in 1956.[1] Its molecular structure was first mentioned implicitly in a markush structure schema appearing in a patent from 1998.[3] It was later explicitly and pharmacologically described in a peer reviewed paper in 2017 by David Nutt and Ezekiel Golan et al.[4] followed by another in February 2018 which detailed the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and metabolism of MEAI by Shimshoni, David Nutt, Ezekiel Golan et al.[5] One year later it was studied and reported on in another peer reviewed paper by Halberstadt et al.[6] The aminoindane family of molecules was, perhaps, first chemically described in 1980.[7][8]

Alcohol substitute

[edit]MEAI was an early candidate of alcohol replacement drugs that came to market during a late 2010s movement to replace alcohol with less-toxic alternatives spearheaded by British psychopharmacologist David Nutt[9][10][11] rippling to the rest of Europe.[12]

In an act of gonzo journalism, Michael Slezak writing for New Scientist, tried and reported on his experience with MEAI[13] after being provided with it by Dr Zee[14] (Ezekiel Golan) after an interview[13] Golan claimed he invented MEAI and originally intended MEAI to be sold as a legal high but instead indicated plans to work with David Nutt and his company DrugScience to develop MEAI further based on Golan's patents as a "binge behaviour regulator"[15] and "alcoholic beverage substitute".[16]

In 2018, a company named Diet Alcohol Corporation of the Americas (DACOA) began openly marketing an MEAI-based drink called "Pace" for sale in the USA and Canada. Pace was described as a 50ml bottle containing 160mg of MEAI in mineral water. Distribution halted after Health Canada released a warning indicating the substance was considered illegal to market for consumption in Canada due to structural similarity to amphetamine.[17][18] In a December 2018 article by CBC News, Ezekiel Golan (Dr Z/Dr Zee) was interviewed and publicly came out as the "lead scientist" of Pace claiming "tens of thousands" of bottles were already sold in Canada.[19] Golan claimed the MEAI featured in Pace was "manufactured in India" and "bottled in Delaware".[19] Health Canada provided a statement to CBC News stating "Pace is an illegal and unauthorized product in Canada." Both Chemistry World[20] and The BBC have dubbed Ezekiel Golan as "the man who invents legal highs".[21] The Guardian called him "the godfather of legal highs"[22] for his contribution in reintroducing substituted cathinone based drugs commonly sold as Bath salts (drug) including Mephedrone

Pharmaceutical development

[edit]On May 26, 2022, MEAI was prepared for FDA registration by Clearmind Medicine Inc.;[23][24][25] Clearmind Medicine claims wide intellectual property holdings to Ezekiel Golan's patents.[26][27][28][29] In March 2022 Clearmind Medicine announced supportive evidence from animal studies in mice attesting to suppression of alcohol consumption.[30] In June 2022 Clearmind Medicine announced promising results from animal studies that showed promise for treating cocaine addiction with MEAI.[31][32]

MEAI, under the developmental code name CMND-100, is under development by Clearmind Medicine for the treatment of alcoholism, cocaine use disorder, metabolic syndrome, and obesity.[2] As of October 2024, it is in the preclinical stage of development for these indications.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Halberstadt AL, Brandt SD, Walther D, Baumann MH (March 2019). "2-Aminoindan and its ring-substituted derivatives interact with plasma membrane monoamine transporters and α2-adrenergic receptors". Psychopharmacology (Berl). 236 (3): 989–999. doi:10.1007/s00213-019-05207-1. PMC 6848746. PMID 30904940.

- ^ a b c "5-Methoxy 2-aminoindane". AdisInsight. 16 October 2024. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ US 5708018, Haadsma-Svensson SR, Andersson BR, Sonesson CA, Lin CH, Waters RN, Svensson KA, Carlsson PA, Hansson LO, Stjernlof NP, "2-aminoindans as selective dopamine D3 ligands", published 1998-01-13, assigned to Pharmacia & Upjohn Co.

- ^ Shimshoni JA, Winkler I, Edery N, Golan E, van Wettum R, Nutt D (March 2017). "Toxicological evaluation of 5-methoxy-2-aminoindane (MEAI): Binge mitigating agent in development". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 319: 59–68. Bibcode:2017ToxAP.319...59S. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2017.01.018. PMID 28167221. S2CID 205304106.

- ^ Shimshoni JA, Sobol E, Golan E, Ben Ari Y, Gal O (March 2018). "Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation of 5-methoxy-2-aminoindane (MEAI): A new binge-mitigating agent". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 343: 29–39. Bibcode:2018ToxAP.343...29S. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2018.02.009. PMID 29458138. S2CID 3879333.

- ^ Halberstadt AL, Brandt SD, Walther D, Baumann MH (March 2019). "2-Aminoindan and its ring-substituted derivatives interact with plasma membrane monoamine transporters and α2-adrenergic receptors". Psychopharmacology. 236 (3): 989–999. doi:10.1007/s00213-019-05207-1. PMC 6848746. PMID 30904940.

- ^ Sainsbury PD, Kicman AT, Archer RP, King LA, Braithwaite RA (2011). "Aminoindanes--the next wave of 'legal highs'?". Drug Testing and Analysis. 3 (7–8): 479–482. doi:10.1002/dta.318. PMID 21748859.

- ^ Cannon JG, Perez JA, Pease JP, Long JP, Flynn JR, Rusterholz DB, Dryer SE (July 1980). "Comparison of biological effects of N-alkylated congeners of beta-phenethylamine derived from 2-aminotetralin, 2-aminoindan, and 6-aminobenzocycloheptene". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 23 (7): 745–749. doi:10.1021/jm00181a009. PMID 7190613.

- ^ Nutt D (23 October 2013). "Decision making about illegal drugs: time for science to take the lead". Nobel Forum, Karolinska Institutet – via YouTube.

- ^ Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD (November 2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis". Lancet. 376 (9752). London, England: 1558–65. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. S2CID 5667719.

- ^ Forster K (24 September 2016). "Hangover free alcohol is finally here". The Independent. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ Wermter B (29 April 2019). "Rauschmittel und gesellschaftliche Probleme" [Drug related societal issues]. Benedict Wermter (in German).

- ^ a b Slezak M (30 December 2014). "High and dry? Party drug could target excess drinking". New Scientist. Retrieved 2022-10-16.

- ^ Slezak M (9 August 2014). "An Interview with Dr Z" (PDF). New Scientist. pp. 1–3. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ US 10406123B2, Golan E, "Binge behavior regulators", issued 2019-09-10

- ^ US 20170360067, Golan E, "Alcoholic beverage substitutes", issued 2017-12-21

- ^ "Advisory - Health Canada warns consumers that Pace, promoted as an alcohol substitute, is unauthorized and may pose serious health risks". Health Canada. 21 December 2018 – via CISION.

- ^ Brunet J (24 April 2019). "FACT CHECK: Is Pace, an "Alcohol Alternative," Legal in Canada?". The Walrus. Toronto, Ontario.

- ^ a b Wright J (8 December 2018). "Is this drink really a new 'alcohol alternative'?". Information Morning Saint John. pp. All. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ Extance A (6 September 2017). "The rising tide of 'legal highs'". Chemistry World. Retrieved 2022-10-17.

- ^ "Meet Dr. Zee - the man who invented legal highs". BBC. 23 January 2018.

- ^ Jonze T (24 May 2016). "Dr Zee, the godfather of legal highs: 'I test everything on myself'". TheGuardian.com.

- ^ "Clearmind Medicine". www.clearmindmedicine.com.

- ^ "Clearmind Medicine Inc". CSE:CMND.

- ^ וינרב, גלי (16 February 2022). "החברה שמנסה להפוך סם פסיכדלי למוצר נגד התמכרות" [The company trying to turn a psychedelic drug into an anti-addiction product]. Globes (in Hebrew).

- ^ US 10137096, Golan E, "Binge behavior regulators", published 2018-11-27

- ^ EP 3230256, Golan E, "Alcoholic beverage substitutes", published 2019-11-13

- ^ EP 3230255, Golan E, "Binge behavior regulators", published 2017-10-18

- ^ "The Science and IP Behind our Treatments". Clearmind.

- ^ "Clearmind Medicine". www.clearmindmedicine.com.

- ^ "Clearmind Medicine". www.clearmindmedicine.com. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ "Clearmind Medicine". www.clearmindmedicine.com. Retrieved 2022-10-16.