18th (Service) Battalion, King's Royal Rifle Corps (Arts and Crafts)

| 18th (Service) Battalion, King's Royal Rifle Corps (Arts & Crafts) | |

|---|---|

Cap badge of the King's Royal Rifle Corps | |

| Active | 4 June 1915–3 February 1920 |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Pals battalion |

| Role | Infantry |

| Size | One Battalion |

| Part of | 41st Division |

| Garrison/HQ | Gidea Park |

| Patron | Maj Sir Herbert Raphael, Bt, MP |

| Engagements | Battle of Flers–Courcelette Battle of the Transloy Ridges Battle of Messines Battle of Pilckem Ridge Battle of the Menin Road Ridge German spring offensive Hundred Days Offensive |

The 18th (Service) Battalion, King's Royal Rifle Corps (Arts and Crafts) (18th KRRC) was an infantry unit recruited as part of 'Kitchener's Army' in World War I. It was raised in the summer of 1915 by the politician Sir Herbert Raphael at Gidea Park in Essex. It served on the Western Front from May 1916, seeing action on the Somme. Later it fought at Messines and Ypres. After a period on the Italian Front it returned to the west to serve against the German spring offensive, when it was almost wiped out. The rebuilt battalion then took part in the final advance to victory in Flanders, before participating in the Allied occupation of the Rhineland.

Recruitment and training

[edit]

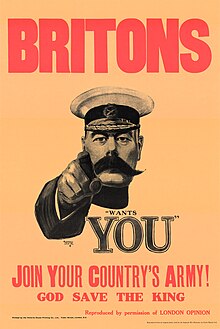

On 6 August 1914, less than 48 hours after Britain's declaration of war, Parliament sanctioned an increase of 500,000 men for the Regular British Army. The newly-appointed Secretary of State for War, Earl Kitchener of Khartoum, issued his famous call to arms: 'Your King and Country Need You', urging the first 100,000 volunteers to come forward. Men flooded into the recruiting offices and the 'first hundred thousand' were enlisted within days. This group of six divisions with supporting arms became known as Kitchener's First New Army, or 'K1'.[1][2] The K2, K3 and K4 battalions, brigades and divisions followed soon afterwards. But the flood of volunteers overwhelmed the ability of the Army to absorb them, and the K5 units were largely raised by local initiative rather than at regimental depots, often from men from particular localities or backgrounds who wished to serve together: these were known as 'Pals battalions'. The 'Pals' phenomenon quickly spread across the country, as local recruiters offered complete units to the War Office (WO). One such unit was the 18th (Service) Battalion, King's Royal Rifle Corps (Arts and Crafts) (18th KRRC) raised by Sir Herbert Raphael, 1st Baronet, MP. He had at one time been an officer in the 1st Volunteer Battalion, Essex Regiment, but had enlisted as a Private in the 24th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers (2nd Sportsmen's) soon after the outbreak of war. In June 1915 he was given the rank of Captain to raise a new battalion. Before the war he had been developing his estate at Gidea Park, Essex, as a 'Garden suburb' as part of the Arts and Crafts movement, and the name became attached to the battalion raised there.[3][4][5][6][7]

Raphael was promoted to Major and served as the second-in-command of 18th KRRC in its early days.[8] Lieutenant-Colonel Newdigate Burne, a retired Indian Army officer, was appointed commanding officer (CO) on 16 August.[9][10] Robert Pennell, who had begun the war as a sergeant and had been badly wounded at the First Battle of the Aisne in 1914, was appointed Regimental Sergeant-Major. By the time the battalion went to France he had been promoted to Temporary Captain.[11] The battalion was taken over by the WO on 4 September 1915.[5] Training continued at Gidea Park[12] until October 1915 when the battalion moved to Witley Camp in Surrey to join 41st Division, the last Kitchener division to be formed. The battalion was assigned to 122nd Brigade, serving alongside 12th (S) Bn, East Surrey Regiment (Bermondsey) ('12th ESR'), 15th (S) Bn, Hampshire Regiment (2nd Portsmouth) ('15th Hants', the 'Pompey Pals'), and 11th (S) Bn, Queen's Own Royal West Kent Regiment (Lewisham) ('11th RWK').[5][7][13][14]

The battalions at Witley were equipped with Lee-Enfield Mark III rifles, specialists such as Lewis gunners, signallers and 'bombers' were selected and trained. Route marches were carried out with full kit, the pouches filled with iron weights (known as 'Kitchener's chocolate') to simulate the weight of ammunition; many of the men discarded these weights in roadside ditches. In November 1915 the battalion moved to Ramillies Barracks, Aldershot, where the men fired their musketry courses, before returning to Witley.[5][13][15] Lieutenant-Col Burne was replaced on 1 February 1916 by Capt George Soltau-Symons, a former KRRC officer who had been recalled on the outbreak of the war and had been acting as a staff officer.[4][9][10] During February 1916 122nd Bde returned to Marlborough Lines, Aldershot, to begin final intensive training prior to going overseas to join the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front.[5][7][13]

On 2 May the battalion boarded three trains at the military siding at Farnborough, bound for Southampton Docks. The men boarded two ships and landed at Le Havre next day.[4][5][7][13][16]

23rd (Reserve) Battalion

[edit]The depot companies of 18th KRRC remained behind when the battalion joined 41st Division, and in December 1915 they were formed into 23rd (Reserve) Battalion, KRRC, to supply reinforcements to 18th KRRC. Its CO was Lt-Col Sir John Hope, 16th Baronet, MP, a former Regular KRRC officer[4] who had been wounded as second-in-command of another Kitchener battalion, 9th KRRC, at Hooge in July 1915.[17] Major Sir Herbert Raphael transferred from 18th KRRC to serve as second-in-command.[8]

By January 1916 23rd KRRC was at Banbury, Oxfordshire, in 26th Reserve Brigade, which moved to Wimbledon Common in June. On 1 September 1916 the Training Reserve was established following the introduction of conscription, and 23rd (R) Bn KRRC became 111th Training Reserve Battalion, though the training staff retained their KRRC badges. The brigade continued to provide reinforcement drafts for the KRRC and the Rifle Brigade. The battalion was disbanded at Wimbledon on 2 March 1918.[3][4][5]

Service

[edit]By 8 May 1916 41st Division had completed its concentration between Hazebrouck and Bailleul in Second Army's area. While continuing its training, including the use of 'gas helmets', parties from the new division were sent up to the line for an introduction to trench warfare from experienced units. 41st Division then relieved 9th (Scottish) Division in the Ploegsteert trenches, with 18th KRRC going into the line on 30 May. It then began a routine of one week in the trenches and one in reserve at the 'Piggeries' or at Papot, usually alternating with the 15th Hants or 26th Royal Fusiliers (Bankers) of 124th Bde. The battalion also had to supply working parties, and it began to suffer a trickle of casualties, particularly from chance shelling or rifle grenade fire. Lieutenant-Col Soltau-Symons was invalided on 13 June and the second-in-command, Maj E.RH. Herbert, took over temporarily. On 25 June Maj Charles Marten (West Yorkshire Regiment), the second-in-command of 32nd Royal Fusiliers (East Ham) in 124th Bde, arrived to take over command of 18th KRRC.[9][13][14][16][18][19][20]

When 41st Division arrived on the Western Front the BEF was preparing for that summer's 'Big Push', the Battle of the Somme, the bombardment beginning on 24 June. To confuse the enemy as to the extent of the offensive, 41st Division was ordered to make diversionary raids at Ploegsteert. The other three battalions of 122nd Bde carried out a large raid on 30 June, and although 18th KRRC was not involved it suffered some casualties from retaliatory shellfire. The battalion carried out its own raid on 12/13 July, but the parties found the enemy barbed wire newly repaired and their trenches strongly held: the raiders withdrew with some casualties. On the night of 5/6 August 18th KRRC and 228th (Barnsley) Field Company, Royal Engineers (RE), carried out an operation under the codename 'Jump' to advance the line by digging new trenches and erecting a new belt of barbed wire in No Man's land. The digging and wiring parties were protected by covering parties and Lewis gun teams. The battalion was congratulated by the division and corps commanders for this work.[16][21][22][23]

Flers–Courcelette

[edit]

On 15 August 18th KRRC left Papot and marched by stages to the Méteren training area, where it began special training before 41st Division joined Fourth Army in the offensive. It moved on 24 August to Brucamps, where the training included operating in a wood similar to the notorious Delville Wood on the Somme. Then on 6 September the battalion entrained at Longpré-les-Corps-Saints station for Méricourt-l'Abbé, whence it marched to bivouacs at Fricourt, which had been captured at the beginning of the Somme Offensive. 41st Division was now ordered to take part in the next phase of the offensive, the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, in which 122nd Bde (code-name 'Jam') on the division's left was to capture the village of Flers. For this its first attack, 41st Division had support from tanks, also making their first ever appearance on a battlefield. Ten Mark I tanks of D Company, Heavy Section, Machine Gun Corps, were assigned to the division, formed up behind the infantry. 122nd Brigade took up its positions north-west of Delville Wood by 02.00 on 15 September. 18th KRRC (code-name 'Jar') was on the left of the brigade's first line with 15th Hants to the right, followed by 12th ESR and 11th RWK respectively. 18th KRRC was to advance on a four-platoon front with each company (A–D right to left) in four platoon waves at 70 yards (64 m) intervals. While the tanks crept into position behind them, the leading waves lay down in No man's land.[16][24][25][26][27][28][29]

Just as the attack was about to start, a single German shell hit 18th KRRC's battalion headquarters, killing Lt-Col Marten, together with the adjutant, signalling officer and trench mortar officer. Nevertheless, at Zero (06.20) the battalion moved forward behind a Creeping barrage, sweeping over 'Tea Support Trench' (which had been almost obliterated by shellfire) and then taking the first (Green Line) objective, 'Switch Trench', by 06.45, just after the tanks reached it. 12th ESR followed close behind, the two battalions getting mixed up. Most of the Germans fled, but a few machine gun teams in Flers caused heavy casualties, particularly among the officers. After a pause for consolidation, the two battalions moved off again at 07.20 behind a barrage with the four tanks that were still in action. Moving quickly, they reached the second (Brown Line) objective, 'Flers Trench'. Their advance had been so fast that 18th KRRC and 12th ESR were now in front of their own creeping barrage. The signallers showed flares and coloured panels to alert the contact aircraft overhead, who ordered the artillery to lift the barrage forwards. While the battalion waited in Flers trench, the first of the tanks (D16, Dracula) arrived, and when the barrage lifted onto Flers village they went forward together over the last 600 yards (550 m) to the village, the tanks flattening the German wire. Other tanks worked up the east and west sides of the village. After confused fighting, Flers (the third or Blue Line objective) was in British hands by 10.30, and the troops began 'mopping up' the dugouts with 'P Bombs' (phosphorus grenades), sending large numbers of prisoners back. Other Germans fled towards Gueudecourt, while their artillery put down a heavy bombardment on Flers. The troops in the village – about 100 of 18th KRRC under Capt R. Baskett, and groups from the other battalions of 122nd Bde and even 124th Bde – were badly disorganised and were cut off by a German barrage laid in their rear. Men of 12th ESR were pushing on through the village with tank D17, Dinnaken, but many of the officers and warrant officers who had gone into action had become casualties and most of the remaining NCOs and ORs were unaware that they were supposed to advance to one final (Red Line) objective, a line of trenches beyond the village. Dinnaken had broken down while withdrawing to the rally point, but two tanks that had accompanied the New Zealand Division up the west side of Flers came out of cover in the village and broke up a German counter-attack. 122nd Brigade gathered what troops it could, including 228th Fd Co, RE, who had been building strongpoints, and stabilised the situation so that the brigade could be relieved by 123rd Bde from 16.30.[13][14][16][26][27][29][30][31][32][33] 18th KRRC went back to the old British lines and reorganised in 'Savoy Trench'. Next day Capt William Moore Alpine, who had been commanding the battalion 'details' at the transport lines, came up and took over temporary command of the battalion, which had a frontline strength of roughly 274 men. Four officers were temporarily attacked from 11th RWK to replace casualties. On 20 September Capt Moore Alpine was promoted to acting Lt-Col to take permanent command of the battalion.[9][16]

Transloy Ridges

[edit]18th KRRC was relieved from the reserve trenches on 18 September and marched back to Dernancourt. It remained in camp reorganising for the rest of the month, then on 2 October it marched up to Mametz Wood. On the night of 3/4 October it relieved troops of the New Zealand Division in 'Goose Alley' and 'Grove Alley', east of Flers, where the New Zealanders had launched the Battle of the Transloy Ridges. The area was under heavy bombardment, and the enemy attempted to bomb their way down 'Gird Trench' nearby, where they were stopped by 15th Hants. 18th KRRC dug new support trenches for 15th Hants during the night of 4/5 October, by which time the battalion had suffered 100 casualties. 122nd and 124th Brigades renewed the offensive operation on the afternoon of 7 October. 18th KRRC in close support to 15th Hants attacked at 13.45, successfully at first, but was then held up by machine gun fire. At dusk the battalion dug a new trench 200 yards (180 m) ahead of where it started. It had casualties of 6 officers and 78 ORs, including some of the battalion transport, caught by shellfire on the Flers road. It was relieved during the night and went back first to Flers Trench and later to Savoy Trench. On 11 October it went back by Decauville Railway to Dernancourt camp.[13][14][16][23][34][35]

Winter 1916–17

[edit]On 18 October 18th KRRC began a series of slow train journeys north, finally marching into 'Chippewa Camp' near Reningelst on 25 October, where 41st Division rejoined Second Army. Over the next six months, the battalions rotated between rest and training at Chippewa Camp and the front and reserve trench lines, either in the Voormezeele area near Dickebusch or the St Eloi sector on the southern side of the Ypres Salient, with 18th KRRC usually alternating with 23rd (2nd Football) Bn, Middlesex Regiment, of 123rd Bde. There was much work to do in maintaining the trenches in the waterlogged ground, under German observation and shellfire from Wytschaete–Messines Ridge, and battalions were relieved every five days, suffering a trickle of casualties on every tour of duty. In October 18th KRRC received drafts of over 500 men, but did not get any significant reinforcements again until the end of December, when 140 partly-trained men arrived from the base, bringing the battalion close to full strength. Lt-Col Moore Alpine left in mid-December and was replaced as CO on 26 December by Maj Charles Kitching (Worcestershire Regiment), who had been second-in-command of 15th Hants. He was promoted to Lt-Col in February and Capt Pennell, who had being acting CO for much of the winter, was promoted to major. 18th KRRC broke its routine in February when it moved from Chippewa Camp to Murrumbidgee Camp at Ridge Wood, where it relieved 10th Queen's Regiment (Battersea) of 124th Bde. It then manned the GHQ line in support when that battalion carried out a large daylight raid on the Hollandscheschuur Salient on 24 February. 18th KRRC returned to 122nd Bde at Voormezeele at the end of the month, and over the following weeks provided working parties for the REs when not in the line. On 7 April it carried out a dummy raid on the mine craters in front of St Eloi, which the artillery bombarded heavily. The Germans responded by blowing a Camouflet, which destroyed about 150 yards (140 m) of the battalion's front line, wounding 17 men.[9][11][16][36][37]

Messines

[edit]

In early 1917 Second Army was preparing for the Battle of Messines. The object of this attack was to capture Messines Ridge with its fine observation positions over the British line. In the weeks before the battle units were withdrawn for careful rehearsals behind the lines, and leaders down to platoon level were taken to see a large model of the ridge constructed at Scherpenberg. 18th KRRC left Chippewa Camp on 25 April for the brigade training area several days' march away at Mentque. At the end of the training, which included a fullscale rehearsal of the brigade's planned attack, 41st Division returned to the Dickebusch area, with 18th KRRC back at Chippewa Camp on 17 May, going into the St Eloi trenches again on 19 May. A mass of heavy, medium and field artillery began systematic destruction of enemy strongpoints and batteries on 21 May and the bombardment became intense from 31 May. The area to be attacked was obvious to the enemy, who bombarded all the roads and railways behind British lines; however the surprise element was the line of 19 great mines dug under the ridge. During the waiting period a 15-man outpost of 18th KRRC was badly hit by German retaliatory fire, but the five unwounded men stayed at their post. On 25 May the battalion raided No 5 Crater at St Eloi under cover of artillery (CXC (Wimbledon) Brigade, Royal Field Artillery (RFA)) and trench mortars and a crossfire by eight Lewis guns firing from the lip of No 3 Crater. The raiders did not secure any prisoners (though a patrol out that night did) but they reconnoitred the crater and as they left they lobbed P Bombs into it to destroy enemy stores. On the night of 6/7 June 18th KRRC left Chippewa Camp and moved up to its concentration area in 'Old French Trench' by 01.10 to wait for Zero hour.[16][38][39][40][41]

The mines were fired at 03.10 on 7 June. With 95,600 pounds (43,400 kg) of ammonal, the St Eloi mine was the largest fired that day and the resulting crater, some 17 feet (5.2 m) deep and 176 feet (54 m) wide, dwarfed all those from former tunnel warfare in the area and left the surroundings strewn with concrete blocks from shattered dugouts. After the mines exploded and the barrage came down the battalions advanced under bright moonlight, although the visibility became bad because of the smoke and dust from the mine explosions and barrage. 123rd Brigade's role was to capture the St Eloi salient by a converging attack as far as the 'Damstrasse', a raised driveway leading to 'White Chateau'. From this first objective (the Blue Line) 122nd Bde was to take over and continue to 'Oblong Reserve Trench' as the second objective (the Black Line). The Blue Line was taken by 05.00 with hardly any resistance, and 122nd Bde moved off at 05.10, leaving 18th KRRC in Old French Trench to follow. Once the brigade was established along the Damstrasse, A and then B Companies moved out at 06.20 along the top of Old French trench and advanced in 'artillery formation' followed by C and D Companies and Battalion HQ. 18th KRRC reached 'Oar Support Trench' (the German second line) at 06.45, where it was the divisional reserve. A Company was sent forward to support 15th Hants, while the other companies provided carrying parties for the brigade. The operation was entirely successful, 18th KRRC's casualties to shellfire amounted to 1 officer and 18 ORs killed and 30 wounded. It was withdrawn to Old French Trench at 22.00.[13][14][16][41][42][43][44][45]

18th KRRC relieved 1/15th Londons (Civil Service Rifles) of 47th (2nd London) Division in the Hollebeke sector on 12/13 June and established Battalion HQ in the ruins of 'White Chateau'. On 14 June the battalion, along with 11th RWK, carried out a small operation to take parts of 'Olive Trench' and 'Optic Trench' that had not been captured on 7 June. B and D Companies led at 19.30, following a creeping barrage that then halted to form a protective standing barrage beyond the objectives. As well as securing the trenches, this successful little operation captured 20 prisoners, two machine guns and a dismantled battery of 5.9-inch howitzers. 18th KRRC's casualties were 3 officers and 9 ORs killed, 2 officers and 59 ORs wounded. Next day the Germans attempted to retake the trenches, but their counter-attack was driven off by artillery and Lewis gun fire. The Germans kept up continuous shellfire on White Chateau, and their aircraft were very active overhead. 18th KRRC was withdrawn into brigade reserve on 16 June, and three days later went back to rest bivouacs at Ridge Wood. Major Pennell took temporary command of 18th KRRC while Lt-Col Kitching went on leave, and then took over 12th ESR during their CO's leave the following month. 122nd Brigade moved to La Roukloshille on 28 June, where it underwent a month's training, which emphasised techniques for overcoming pillboxes and culminated in fullscale practice attacks on 20 and 22 July.[16][41][46][47][48]

Ypres

[edit]On 23 July 41st Division returned to the line for the opening of the Flanders Offensive (the Third Battle of Ypres). Once again 18th KRRC relieved the 1/15th Londons, taking over Optic Trench on the night of 24/25 July. Next day a shell burst in the HQ dugout, setting fire to a store of flares and causing casualties, including wounding the adjutant. On 27 July Battalion HQ was moved into the canal bank near the Iron Bridge. There were rumours that the Germans had pulled back, so units were ordered to send out patrols. One of 18th KRRC's patrols surprised and captured some Germans in a defended shellhole, but were themselves attacked by more Germans emerging from a dugout and only half the patrol got back, without the prisoners. On 29 July it began to rain, flooding the trenches and making movement difficult. After days of bombardment the offensive began on 31 July with the Battle of Pilckem Ridge. Second Army had a minor role in covering the right flank of the main offensive by Fifth Army: 41st Division made an attack on either side of the Ypres–Comines Canal with limited objectives. 122nd Brigade on the south of the canal attacked from Optic Trench with 18th KRRC (right) and 11th RWK (left), the objectives being the German Front line (the Red Line), Forret Farm and the Hollebeke crossroads (Blue Line), and just beyond that the Green Line, exactly as they had rehearsed at La Roukloshille. The two battalions each took 500 men into action, attacking in two waves on a two-company front, the first wave to take the Red Line and the second to pass through to the Green Line. 18th KRRC detailed special mopping-up parties for the dugouts at Forret Farm, at Hollebeke village and to its south-east, and the roads between the Red and Green lines. The battalion was accompanied by a party from 122nd TMB carrying two Stokes mortars and 80 rounds, and a section of 122nd MG Company to mount a Vickers gun at each of the four strongpoints planned in the battalion's area. One platoon of 18th KRRC was attached to 228th Fd Co, RE, to dig a new communication trench forward from Optic trench. The artillery ([[Shrapnel shell]) and machine gun barrage came down at 03.50 and 122nd Bde advanced to the attack, the enemy's counter-barrage falling behind them as they advanced. The Red Line was easily taken, but the second objective proved much tougher: the dugouts had not been touched by the artillery and were strongly held, while the attacking troops ran into uncut wire. 11th RWK gained a foothold in Hollebeke by 11.30, but 18th KRRC was held up in front of Forret Farm, which was strongly defended. Most of their rifles and Lewis guns were clogged with mud. The second wave had lost direction and got mixed up with 11th RWK, losing the barrage and leaving the farm unattacked on their right. A Stokes mortar was sent up to bombard the farm dugouts but was put out of action after firing just five rounds. Repeated orders were sent for one of the first wave companies consolidating the Red Line to go forward and rush the farm, but none of the runners got through the German barrage with the message. Captain Baskett was sent up to take control, but he was wounded. The survivors of C and D Companies dug in where they were. At the time 12th ESR was providing carrying parties for the assaulting battalions, and at 16.30 Acting Lt-Col Pennell was ordered to take 12th ESR forward to complete the capture of Hollebeke. The coloured flare to indicate success was fired at 19.59 and 12th ESR established a line near 'Forret Farm' just beyond the village, which it consolidated. 18th KRRC was withdrawn that night, having suffered 5 officers and 21 ORs killed or died of wounds, 2 officers and 88 ORs wounded, 37 ORs missing. (12th ESR captured Forret Farm next day when it was found to be abandoned, and then recovered it again after a German counter-attack on 5 August, for which A/Lt-Col Pennell received a DSO.)[13][14][16][49][50][51][52]

18th KRRC remained in the trenches until 14 August, when it went La Roukloshille for rest and reorganisation. On 21 August it moved by motor bus to Westbécourt, near St Omer, where 41st Division underwent training. The men were practised in the specialisations (Lewis gunners, bombers and rifle grenadiers) required by the new 'fighting platoon' tactics, which the battalion practised over a 'shell-hole' training area. The training emphasised rifle grenades for use against the number of enemy pillboxes now being encountered. The battalion received over 130 reinforcements. Major Pennell had returned to 18th KRRC and on 7 September assumed command of the battalion, being promoted to Temporary Lt-Col on 22 September.[9][11][16][16][52][53][54]

On 14 September the battalion began marching by stages back to the Ypres Salient as 41st Division moved into its positions by the canal for the next attack up onto the 'Tower Hamlets' spur. On 17 September 18th KRRC moved into overcrowded positions around Mount Sorrel, where it suffered heavy casualties from shellfire. When the jumping-off line was pegged out in No man's land, it was discovered that the area of 'Bodmin Copse' was a marsh, which would split the battalion in two, and the assembly was extremely difficult. The division formed up on the night of 19/20 September. 122nd Brigade was on the left, with 18th KRRC in the first line on the right followed by 12th ESR, each battalion being on a two company frontage and each accompanied by a mortar team and a two-gun subsection of the brigade MG company. The barrage began at 05.40 and paused for 3 minutes for the first wave to close up, then began creeping towards the first objective. 18th KRRC was held up by a pillbox in the Bassevillebeek valley just beyond Bodmin Copse. 12th ESR came up in support and after half an hour the enemy were dispersed with rifle grenades. The battalion secured its first and second objectives, and formed a defensive flank to the right, where 124th Bde was held up. 12th ESR then passed through to advance on the Green Line, but it was badly hit by fire from the right and only gained its objective late in the day with heavy casualties. The positions were shelled all next day and 122nd was still affected by enfilade fire from the right, where 123rd Bde had taken over from 124th Bde but had still not got onto the Tower Hamlets spur. The Germans made three counter-attacks during the afternoon and evening but 18th KRRC's posts held firm. The battalion was relieved on the night of 22/23 September, going back to Ridge Wood and then by train to Caëstre.[13][14][16][52][55][56][57]

41st Division was now sent to the Flanders Coast, with 18th KRRC in divisional reserve at Bray-Dunes, near Dunkirk, where it reorganised and trained. On 15 October it went into the coast defences at La Panne, where Lt-Col Pennell (who had been awarded a Bar to his DSO) took temporary command of 122nd Bde. The battalion received 190 reinforcements, mainly men 'combed out' from the Army Service Corps and the Army Ordnance Corps.[13][14][16][58][59]

Italy

[edit]On 7 November 1917 41st Division was informed that it was to be transferred to reinforce the Italian Front, and entrainment began on 12 November.[13][14][60][61][62] The division completed its concentration in the Mantua area by 18 November. 122nd Brigade then undertook a five-day march of 120 miles (190 km) to take up positions in the Montello sector. The gruelling march was conducted in battle order with advanced guards and night outposts. The advance guard for 122nd Bde under Lt-Col Pennell consisted of 18th KRRC, a section of 122nd MG Co, a battery of 187th (Fulham) Brigade, RFA, and 228th Fd Co, RE. On 1 December the brigade took over a sector of the front line along the River Piave. On 16–17 January 1918 the brigade marched to billets in Loria, where it remained training for a month before moving to Venegazzù in the Monte Grappa sector. While there the division received orders to return to the Western Front. The division concentrated in the Camposampiero entraining area and 18th KRRC entrained at Fontaniva in two halves on 1 and 2 March. It detrained at Mondicourt in the Somme sector on 5 March, going into billets at Pommera, where 41st Division was in GHQ Reserve.[13][14][5][59][63][64][65][66]

The BEF was suffering a manpower crisis in early 1918, and each infantry brigade was reduced from four to three battalions, the surplus units being disbanded and drafted to provide reinforcements. When 41st Division arrived from Italy it conformed to the new organisation, and 11th RWK was disbanded from 122nd Bde, while 18th KRRC received a draft of 2 officers and 130 ORs from 21st KRRC (Yeoman Rifles), which was being disbanded from 124th Bde.[5][7][13][14][66][67]

Spring Offensive

[edit]41st Division was preparing to reinforce Third Army. Early on 21 March 18th KRRC entrained at Mondicourt for the Edgehill training area near Albert, Somme, but the long-anticipated German spring offensive began that morning and Third Army was soon under intense pressure. 41st Division 's trains were redirected to Achiet-le-Grand where the battalion detrained about 01.00 on 22 March, leaving the station just before the Germans began to shell it. It marched to Savoy Camp near Bihucourt. At 06.00 next morning 41st Division was ordered into IV Corps' Reserve area, and 18th KRRC set off at 11.00 to a position between Favreuil and Sapignies in the rear defence zone (the 'Green Line'). That night and the following morning (23 March) the battalion dug a new line behind Beugnâtre while the Germans shelled the nearby airfield. At 23.00 the battalion was ordered up into the line west of Beugny and came under the command of 123rd Bde. About 10.00 on 24 March Lt-Col Pennell was wounded by a sniper and was evacuated across the open. Major William Bristowe of A Company (one of the officers from 21st KRRC) assumed temporary command in his place. There was a certain amount of shelling, and 123rd Bde warned that the danger was likely to come from the right. At about 15.00 the troops to the right of the battalion were seen to be retreating and C Company was sent out as a flank guard. Heavy rifle and machine gun fire came from that flank, but smoke from a burning dump hid the enemy's movements. At 15.30 troops to the left were also seen withdrawing, and an attempt was made to extricate the battalion before it was surrounded. All four companies were now heavily engaged and the enemy was advancing fast on both flanks, but belts of wire behind the front and support lines and a hostile barrage behind the battalion made it difficult to escape. With an enemy machine gun enfilading the escape route from a nearby railway embankment, casualties during the withdrawal were very heavy. The remnants of the battalion were collected in the defences they had dug on 21–22 March, but the flanks were open and they were forced to withdraw from that line as well. That night (24/25 March) what was left of 123rd Bde was gathered at Bihucourt. 18th KRRC's casualties had been approximately 15 officers and 475 ORs. The survivors, together with those of 123rd Bde, dug two lines of trenches in front of Bienvillers to protect the road to Achiet-le-Grand, the enemy already being in Bapaume. However, next morning this line became untenable as the enemy worked their way up the valley between Bienvillers and Favreuil. 41st Division gradually fell back to a position along the Albert–Achiet-le-Grand railway line. That night (25/26 March) the division was relieved on this line, but the remnant of 18th KRRC could not find the rest of 122nd Bde and spent the night at Essarts. Next morning it linked up with 122nd Bde and picked up a party of the battalion (mainly from C Company) who had become detached during the fighting. It was withdrawn to Bienvillers and spent the very cold night of 26/27 March in a field. It spent 27 March reorganising in a wood at Bienvillers, on 28/29 March it moved into the support line behind Gommecourt. On 29/30 March it relieved a battalion of 42nd (East Lancashire) Division in the support line behind Bucquoy. Here it was joined by some stragglers and reorganised into two companies. However, apart from some shelling, all was quiet: the Germans had been stopped at Bucquoy and the 'Great Retreat' was over.[13][14][66][67][68][69][70]

Ypres Salient

[edit]

41st Division was finally relieved on the night of 1/2 April after 10 days' fighting, and was taken by motor bus to a rest area. It then moved north by marching and train to rejoin Second Army at Ypres, which was now considered a quiet area. 18th KRRC rested at 'School Camp' at Poperinge where it received large reinforcement drafts, bringing the battalion back up to a strength of 26 officers and 917 ORs, organised as four companies once more. On the night of 6/7 April the battalion took over the support line in the Passchendaele sector, at the head of the salient that had been captured during the Third Battle of Ypres. After four days 18th KRRC was relieved. The Germans had launched the second phase of their Spring offensive (the Battle of the Lys) just south of Ypres and made such rapid progress that by 12 April the position in the Passchendaele salient was critical and the defenders were thinned out in readiness for a withdrawal. 18th KRRC went up that night to take over the whole brigade front, with two companies holding each battalion frontage. Over the following days the troops salvaged equipment and destroyed the dugouts and then early on 16 April 18th KRRC withdrew its outposts and marched back to 'Salvation Camp' just outside Ypres as the Passchendaele Salient was evacuated. On 19 April the battalion moved to 'Warrington Camp' and spent the rest of the month working on a new defence line in front of Ypres. On 24 April Lt-Col Sir John Lees, 3rd Baronet, arrived to take over command of the battalion from Maj Bristowe. On 29 and 30 April 18th KRRC 'stood to' ready to move at short notice as the Germans made their last effort south-west of Ypres. The battalion was not called upon, but suffered a number of casualties as its camp was shelled. It took over the front line from 3 to 17 May and then from 26 May to 3 June, leaving the raw recruits behind for training at Brandhoek and other camps. When not in the line the battalion worked on the 'Green Line' defences. By now it was at full strength: 46 officers and 1120 ORs. On 4–5 June the battalion travelled by rail to Hellebrouck in the Second Army Training Area where 41st Division underwent intensive training, then on 24–26 June the battalion marched to billets at Abeele Aerodrome when 41st Division went into reserve for XIV French Corps. On 1/2 July the battalion relieved a battalion of the 103rd French Infantry Regiment in the support positions at La Clytte, from which it began alternating with the other battalions of 122nd Bde in the front line. German artillery was fairly active against these positions and 18th KRRC patrolled aggressively.[13][14][66][71][72][73]

Hundred Days Offensive

[edit]On 8 August, when the Allied Hundred Days Offensive began further south with the Battle of Amiens, Second Army stood fast, but 122nd Bde's front was particularly active: 15th Hants carried out a night attack to straighten the brigade front, which 18th KRRC then took over. On 11 August the Germans carried out a strong counter-attack following a heavy morning bombardment: it drove in 18th KRRC's left company front where one platoon was isolated and overrun. The rest of the company then reorganised and retook all the ground except the isolated post. The right company drove off the attack on their front and those who had got behind their left flank were driven out by the company's left support platoon with 'sword' (the riflemen's term for bayonet) and rifle. By 08.00 the situation had reverted to normal. The battalion's casualties were 3 officers and 4 ORs killed, 2 officers and 20 ORs wounded, 1 officer and 19 ORs missing. Early on 24 August the enemy put down a heavy barrage and attacked four of the battalion's forward posts, overrunning two of them as well as 'Clydesdale Camp'. That evening 18th KRRC sent platoon-strength fighting patrols against each of the four posts, finding two still held by the battalion and bombing the Germans out of one. However, they could make no progress against No 5 Post or Clydesdale Camp. An attempt the following evening to get from No 4 Post behind No 5 Post failed when the officer was killed and the men returned. The battalion was relieved before it could make another attempt, having lost 3 officers and 8 ORs killed, 20 ORs wounded and 7 missing over the two days.[66][74]

On 28 August 41st Division began to be relieved by 27th US Infantry Division and 18th KRRC went by train to billets in Esquerdes, near St Omer. However, on the evening of 30 August the Germans were seen to be shelling their own line and patrols from 41st Division found that the enemy had retired. 41st and 27th US Divisions immediately began following up, and 18th KRRC was recalled from its billets, moving into reserve at Vierstraat on the night of 2/3 September and relieving American troops who had been engaged in heavy fighting. While the rest of 122nd Bde attacked, 18th KRRC remained in reserve, being heavily shelled with Mustard gas and taking part in a small operation to straighten the line on 4/5 September. It went to Hoograaf for rest 6–13 September before returning to Vierstraat to hold the outposts from 14 to 20 September. On 21 September 122nd Bde went back to Abeele for training, with special emphasis on dealing with strongpoints and machine gun nests.[13][14][66][66][75][76]

The Allies launched a coordinated series of offensives on 26–29 September. Second Army's attack (the Fifth Battle of Ypres) began on 28 September: there was little resistance. 122nd Brigade joined in the pursuit next day with 18th KRRC engaging the enemy at Villers Farm and suffering about 90 casualties. It spent the night at the farm. On 1 October 122nd Bde advanced towards Menin, but when the mist cleared it was held up by a strong line of machine gun posts at Geluwe. At 19.30 18th KRRC was ordered to make an immediate attack and the battalion struggled to make the arrangements while under heavy artillery fire: Brigade HQ agreed to defer the attack until next morning. 18th KRRC and 15th Hants accordingly attacked at 07.00 on 2 October and by midday had advanced the line and gained touch with the formations on the flanks. The unit on the left flank was driven back by a counter-attack at 17.45, so 18th KRRC had to withdraw its left to form a flank guard along the Wervicq–Geluwe railway, abandoning two German field guns that it had captured. Next day 122nd Bde went back into divisional reserve. 18th KRRC had lost 3 officers and 27 ORs killed, 10 officers and 167 ORs wounded, and 38 ORs missing, though it received some reinforcements while it was at Dallington Camp.[13][14][66][76][77][78]

On 11 October 18th KRRC went up by train to 'Stirling Castle' on the Menin Road to prepare for the next attack (the Battle of Courtrai). The barrage opened at 05.32 on 14 October and 122nd Bde attacked with 18th KRRC on the right. Despite the confusion of advancing through the fog and smokescreen the battalion reached the Blue Line objective at 09.00 and pushed on to the Red Line where it reorganised. 122nd Brigade remained in support next day, then marched several miles east on 16 October to stay in support for 123rd Bde as the pursuit accelerated and the first liberated Belgian civilians began to be seen. 18th KRRC remained at Gulleghem under intermittent shelling until 19 October, when it crossed the River Lys to the outskirts of Courtrai. 41st Division attacked again on 21 October to close up to the River Scheldt east of the Courtrai-Le Bossuyt Canal, a 9,000 yards (8,200 m) advance for 122nd Bde. The attack began at 07.15, 18th KRRC having sections of Vickers guns, field artillery and engineers attached. The battalion successfully crossed the canal by the Pont Levis No 2 bridge, which was damaged but passable by infantry; the attached engineers began repairs and the Vickers guns were posted to cover the canal. With the field guns engaging enemy machine guns, the battalion pressed on almost to the Hoogmolen ridge. It was then ordered to pull back to allow for an artillery bombardment and then resume the attack at 12.15. However, the attack orders did not arrive until 12.58, by which time the bombardment had ceased and the battalion was unable to regain the ground it had given up. 122nd Brigade issued preliminary orders for a new attack that afternoon, but by then the neighbouring division was already attacking the same objective and its artillery caused casualties among 18th KRRC. In the chaotic conditions, 18th KRRC found that the forming-up area assigned for next morning's attack was still in enemy hands and a company had to clear this before Zero. The left attack was unnecessary, the neighbouring division already having cleared the ground, but the right lost direction and got too far ahead, an officer and 20 men subsequently being reported missing. The advance was halted at 12.15 and 122nd Brigade was rested until 26 October. On that day 18th KRRC and 12th ESR prepared to assault Avelgem on the Scheldt. However, just before Zero civilians reported the town abandoned, which was confirmed by patrols from the battalions, who secured the riverbank. 18th KRRC went back to rest billets in Bellegem next day. It returned to the line on 31 October. The battalion suffered a few more casualties from shelling over the next few days, but it had made its last attack. On 8 November it carried out a dress rehearsal on the Lys for a proposed night assault crossing of the Scheldt, but this became unnecessary when the enemy retreated. 18th KRRC crossed the river and was at Nukerke, south of Oudenaarde, when the Armistice with Germany came into force on 11 November day.[5][13][14][66][76][79][80]

Post-Armistice

[edit]On 12 November 41st Division learned that it had been selected to form part of the Allied occupation forces in Germany. 18th KRRC carried out a series of marches until it reached Zarlardinge on 21 November, where it was billeted until 13 December, when it resumed its march, reaching Villers-le-Bouillet on 22 December. Here it stayed into the new year and demobilisation got under way. On 9 January 1919 the battalion entrained at Huy for the last part of its journey into Germany, crossing the Rhine and detraining at Bensberg, east of Cologne. It was stationed in the adjoining villages of Hoffnungsthal and Volberg, where it took up duties in the Cologne Bridgehead, as brigade reserve to 12th ESR which manned the outpost line. 18th KRRC itself took over the outpost line on 14 February.[13][14][66]

On 27 February 1919 18th KRRC was transferred from 41st Division to 2nd Division, joining 99th Bde at Niederaußem. The British occupation force was designated British Army of the Rhine on 15 March, and 2nd Division was converted into the Light Division, with 18th KRRC brigaded with 13th KRRC and 20th KRRC (British Empire League) in 1st Light Brigade. As men were progressively demobilised, the battalion was kept up to strength by absorbing 52nd (Service) Bn KRRC (a former training battalion from England) on 10 April. In November 1919 the Light Division was abolished and 1st Light Brigade became the Light Brigade in the Independent Division. These in turn were disbanded in January–February 1920 and 18th (Service) Battalion, King's Royal Rifle Corps (Arts & Crafts) was disbanded on 3 February.[3][66][81]

Memorials

[edit]The KRRC's World War I memorial, with sculpture by John Tweed, stands near the west door of Winchester Cathedral.[82][83][84]

There is also a memorial on Wimbledon Common to the 19th, 22nd and 23rd Reserve Battalions of the King's Royal Rifle Corps who trained there in 1916–18 as part of 26th Reserve Brigade.[85]

The 41st Division memorial is at Flers, the bronze figure by Albert Toft being a copy of his Royal Fusiliers War Memorial in London.[86][87]

Insignia

[edit]In addition to the KRRC's black cap badge and metal 'K.R.R.' title on the shoulder strap, the battalion wore a cloth badge on the upper arm when it first arrived in France. This is described as a green arc with a central V shape worn on both shoulder seams, but had disappeared in 1917. Some of the men unofficially wore the KRRC badge on the front of their helmet. 41st Division's formation sign was a white diagonal stripe across a coloured square, which was green in the case of 122nd Bde. This was not worn on the uniform but only on vehicles and signboards. Battalion transport vehicles carried a numeral on this sign; as the junior battalion in the brigade, 18th KRRC's numeral would have been '4'.[88][89][90] For the Battle of Flers-Courcelette every 10th man in the 122nd Bde carried a small piece of mirror attached to his back, so that observers in the rear could monitor their progress.[26] At Messines each man of the brigade carrying party provided by D Company wore a yellow band.[16]

Notes

[edit]- ^ War Office Instructions No 32 (6 August) and No 37 (7 August).

- ^ Becke, Pt 3a, pp. 2 & 8.

- ^ a b c Frederick, p. 245.

- ^ a b c d e Hare, pp. 94–6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j James, p. 95.

- ^ War Office Instruction No 56 of September 1915, Appendix IX.

- ^ a b c d e KRRC at Long, Long Trail.

- ^ a b Who Was Who.

- ^ a b c d e f KRRC at Infantry Battalion Commanding Officers of the British Armies in the First World War (archived at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ a b London Gazette, 10 February 1916.

- ^ a b c Aston & Duggan, p. 139.

- ^ 'Albert's Story' at Milton Keynes Heritage Association.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Becke, Pt 3b, pp. 109–15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q 41st Division at Long, Long Trail.

- ^ Pearse & Sloman, Vol II, p. 28.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q 18th KRRC War Diary 2 May 1916–31 October 1917, The National Archives (TNA), Kew, file WO 95/2635/3.

- ^ 9th KRRC at Great War Forum.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 23–30.

- ^ Eden, pp. 75–9.

- ^ Pearse & Sloman, Vol II, pp. 183–4.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 30–40.

- ^ Eden, pp. 79–81.

- ^ a b Pearse & Sloman, Vol II, pp. 252–3.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 36–45.

- ^ Miles, 1916, Vol II, pp. 299, 321–2.

- ^ a b c Miles, 1916, Vol II Appendices 28 & 29.

- ^ a b Pearse & Sloman, Vol II, pp. 253–4.

- ^ Pidgeon, pp. 71–7.

- ^ a b '15 September 1916 – Supporting 41st Division' at Landships.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 46–51.

- ^ Hare, pp. 167–9.

- ^ Miles, 1916, Vol II, pp. 322–3, 330, Sketch 37.

- ^ Pidgeon, pp. 78–86.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 53–61.

- ^ Miles, 1916, Vol II, p. 436.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 61–98.

- ^ Pearse & Sloman, Vol II, pp. 256–8.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 98–111.

- ^ Eden, pp. 134–41.

- ^ Edmonds, 1917, Vol II, pp. 34, 41–5, Sketch 3.

- ^ a b c Pearse & Sloman, Vol III, pp. 84–8.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 111–6.

- ^ Eden, pp. 141–3.

- ^ Edmonds, 1917, Vol II, pp. 65–9.

- ^ Hare, p. 213.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 117–24.

- ^ Edmonds, 1917, Vol II, p. 147.

- ^ Hare, p. 214.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 125–41.

- ^ Edmonds, 1917, Vol II, p. 149, Sketch 11.

- ^ Hare, pp. 225–6.

- ^ a b c Pearse & Sloman, pp. 89–92.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 147–51.

- ^ Griffith, pp. 77–9.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 151–71.

- ^ Edmonds, 1917, Vol II, pp. 253–5, 261.

- ^ Hare, p. 240.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 172–6.

- ^ a b Pearse & Sloman, pp. 92–5.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 176–8.

- ^ Edmonds, 1917, Vol II, p. 352.

- ^ Edmonds & Davies, pp. 88–9.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 176–98.

- ^ Edmonds & Davies, pp. 95, 99–102, 105, 150–1.

- ^ Edmonds, 1918, Vol I, pp. 83, 115, 131.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k 18th KRRC War Diary 1 March 1918–29 March 1919, TNA file WO 95/2635/4.

- ^ a b Hare, pp. 326–9.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 202–4, 211.

- ^ Edmonds, 1918, Vol I, pp. 249, 253, 384–7, 435–41, 483, Sketches 16–9.

- ^ Pearse & Sloman, Vol III, pp. 149, 151.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 222–46.

- ^ Edmonds, 1918, Vol II, pp. 105, 140, 274–5, 326, Sketches 21–4.

- ^ Pearse & Sloman, Vol III, pp. 151–3.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 246–9.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 249–58.

- ^ a b c Pearse & Sloman, Vol III, pp. 215–22.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 260–6.

- ^ Edmonds & Maxwell-Hyslop, 1918, Vol V, pp. 78–9, 88, Sketch 9.

- ^ Aston & Duggan, pp. 266–80.

- ^ Edmonds & Maxwell-Hyslop, 1918, Vol V, pp. 273–4, 432–3, 435–6, 443, Sketches 22, 24, 32–3.

- ^ Rinaldi.

- ^ IWM WMR Ref 21928.

- ^ War Memorials Online Ref 102162.

- ^ Quinlan, p. 72.

- ^ IWM WMR Ref 12192.

- ^ Pidgeon, p. 100.

- ^ Quinlan, p. 58.

- ^ Bilton, pp. 17, 22, 265–7.

- ^ Elderton & Gibbs, p. 52.

- ^ Hibberd, p. 45.

References

[edit]- J. Aston & L.M. Duggan, The History of the 12th (Bermondsey) Battalion East Surrey Regiment, Union Press, 1936/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2005, ISBN 978-1-845742-75-1.

- Maj A.F. Becke,History of the Great War: Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 3a: New Army Divisions (9–26), London: HM Stationery Office, 1938/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2007, ISBN 1-847347-41-X.

- Maj A.F. Becke,History of the Great War: Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 3b: New Army Divisions (30–41) and 63rd (R.N.) Division, London: HM Stationery Office, 1939/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2007, ISBN 1-847347-41-X.

- David Bilton, The Badges of Kitchener's Army, Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2018, ISBN 978-1-47383-366-1.

- Brig-Gen Sir James E. Edmonds, History of the Great War: Military Operations, France and Belgium 1917, Vol II, Messines and Third Ypres (Passchendaele), London: HM Stationery Office, 1948/Uckfield: Imperial War Museum and Naval and Military Press, 2009, ISBN 978-1-845747-23-7.

- Brig-Gen Sir James E. Edmonds & Maj-Gen H.R. Davies, History of the Great War: Military Operations, Italy 1915–1919, London: HM Stationery Office, 1949/Imperial War Museum, 1992, ISBN 978-0-901627742/Uckfield: Naval and Military Press, 2011, ISBN 978-1-84574-945-3.

- Brig-Gen Sir James E. Edmonds, History of the Great War: Military Operations, France and Belgium 1918, Vol I, The German March Offensive and its Preliminaries, London: Macmillan, 1935/Imperial War Museum and Battery Press, 1995, ISBN 0-89839-219-5/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2009, ISBN 978-1-84574-725-1.

- Brig-Gen Sir James E. Edmonds, History of the Great War: Military Operations, France and Belgium 1918, Vol II, March–April: Continuation of the German Offensives, London: Macmillan, 1937/Imperial War Museum and Battery Press, 1995, ISBN 1-87042394-1/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2009, ISBN 978-1-84574-726-8.

- Brig-Gen Sir James E. Edmonds & Lt-Col R. Maxwell-Hyslop, History of the Great War: Military Operations, France and Belgium 1918, Vol V, 26th September–11th November, The Advance to Victory, London: HM Stationery Office, 1947/Imperial War Museum and Battery Press, 1993, ISBN 1-870423-06-2/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2021, ISBN 978-1-78331-624-3.

- Clive Elderton & Gary Gibbs, World War One British Army Corps and Divisional Signs, Wokingham: Military History Society, 2018.

- J.B.M. Frederick, Lineage Book of British Land Forces 1660–1978, Vol I, Wakefield: Microform Academic, 1984, ISBN 1-85117-007-3.

- Paddy Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Western Front: The British Army's Art of Attack 1916–18, Newhaven, CT, & London: Yale University Press, 1994, ISBN 0-300-05910-8.

- Maj-Gen Sir Steuart Hare, The Annals of the King's Royal Rifle Corps, Vol V: The Great War, London:John Murray. 1932/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2015, ISBN 978-1-84342-456-8.

- Mike Hibberd, Infantry Divisions, Identification Schemes 1917, Wokingham: Military History Society, 2016.

- Brig E.A. James, British Regiments 1914–18, London: Samson Books, 1978, ISBN 0-906304-03-2/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2001, ISBN 978-1-84342-197-9.

- Capt Wilfred Miles, History of the Great War: Military Operations, France and Belgium 1916, Vol II, 2nd July 1916 to the End of the Battles of the Somme, London: Macmillan, 1938/Imperial War Museum & Battery Press, 1992, ISBN 0-89839-169-5/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2005, ISBN 978-1-84574-721-3.

- Capt Wilfred Miles, History of the Great War: Military Operations, France and Belgium 1916, Vol II, Appendices, London: Macmillan, 1938/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2005, ISBN 978-1-84574-847-0.

- Trevor Pidgeon, Battleground Europe: Somme: Flers and Gueudecourt, Barnsley: Leo Cooper, 2002, ISBN 0-85052-778-3.

- Mark Quinlan, Sculptors and Architects of Remembrance, Sandy, Bedfordshire: Authors Online, 2007, ISBN 978-0-755203-98-7.

- Richard A. Rinaldi, The Original British Army of the Rhine, 2006.

- Instructions Issued by The War Office During August, 1914, London: HM Stationery Office, 1916.

- Instructions Issued by The War Office During September 1915, London: HM Stationery Office.

- Who Was Who.