Protests against Nicolás Maduro

| Protests against Nicolás Maduro | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the crisis in Venezuela | |||

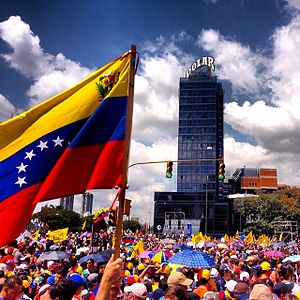

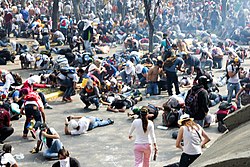

Images from top to bottom and from left to right:

| |||

| Date | 12 February 2014 – ongoing (11 years) | ||

| Location | Venezuela, worldwide | ||

| Status | Ongoing | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

| |||

| Number | |||

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | |||

| Injuries | |||

| Arrested | |||

In 2014, a series of protests, political demonstrations, and civil insurrection began in Venezuela due to the country's high levels of urban violence, inflation, and chronic shortages of basic goods and services.[23][24][25] Explanations for these worsening conditions vary,[26] with analysis blaming strict price controls,[27][28] alongside long-term, widespread political corruption resulting in the under-funding of basic government services. While protests first occurred in January, after the murder of actress and former Miss Venezuela Mónica Spear,[29][30] the 2014 protests against Nicolás Maduro began in earnest that February following the attempted rape of a student[31] on a university campus in San Cristóbal. Subsequent arrests and killings of student protesters spurred their expansion to neighboring cities and the involvement of opposition leaders.[32][33] The year's early months were characterized by large demonstrations and violent clashes between protesters and government forces that resulted in nearly 4,000 arrests and 43 deaths,[7][8][20] including both supporters and opponents of the government.[34] Toward the end of 2014, and into 2015, continued shortages and low oil prices caused renewed protesting.[35]

By 2016, protests occurred following the controversy surrounding the 2015 Venezuelan parliamentary elections as well as the incidents surrounding the 2016 recall referendum. On 1 September 2016, one of the largest demonstration of the protests occurred, gathered to demand a recall election against President Maduro. Following the suspension of the recall referendum by the government-leaning National Electoral Council (CNE) on 21 October 2016, the opposition organized another protest which was held on 26 October 2016, with hundreds of thousands participating while the opposition said 1.2 million participated.[36] After some of the largest protests occurred in a late-2016, Vatican-mediated dialogue between the opposition and government was attempted and ultimately failed in January 2017.[37][38] Concentration on protests subsided in the first months of 2017 until the 2017 Venezuelan constitutional crisis occurred when the pro-government Supreme Tribunal of Justice of Venezuela attempted to assume the powers of the opposition-led National Assembly and removed their immunity, though the move was reversed days later, demonstrations grew "into the most combative since a wave of unrest in 2014".[39][40][41][42]

During the 2017 Venezuelan protests, the Mother of all Protests involved from 2.5 million to 6 million protesters.[citation needed] The 2019 protests began in early January after the National Assembly declared the May 2018 presidential elections invalid and declared Juan Guaidó acting president, resulting in a presidential crisis. The majority of protests have been peaceful, consisting of demonstrations, sit-ins, and hunger strikes,[43][44] although small groups of protesters have been responsible for attacks on public property, such as government buildings and public transportation. Erecting improvised street barricades, dubbed guarimbas, were a controversial form of protest in 2014.[45][46][47][48] Although initially protests were mainly performed by the middle and upper classes,[49] lower class Venezuelans became involved as the situation in Venezuela deteriorated.[50] Nicolas Maduro's government characterized the protests as an undemocratic coup d'etat attempt,[51] which was orchestrated by "fascist" opposition leaders and the United States,[52] blaming capitalism and speculation for causing high inflation rates and goods scarcities as part of an "economic war" being waged on his government.[53][54] Although Maduro, a former trade union leader, says he supports peaceful protesting,[55] the Venezuelan government has been widely condemned for its handling of the protests. Venezuelan authorities have gone beyond the use of rubber pellets and tear gas to instances of live ammunition use and torture of arrested protesters according to organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch,[56][57] while the United Nations has accused the Venezuelan government of politically motivated arrests,[58][59][60] most notably former Chacao mayor and leader of Popular Will, Leopoldo Lopez, who has used the controversial charges of murder and inciting violence against him to protest the government's "criminalization of dissent".[61][62] Other controversies reported during the protests include media censorship and violence by pro-government militant groups known as colectivos.

On 27 September 2018, the United States government declared new sanctions on individuals in Venezuelan government. They included Maduro's wife Cilia Flores, Vice President Delcy Rodriguez, Minister of Communications Jorge Rodriguez and Defense Minister Vladimir Padrino.[63] On 27 September 2018, the UN Human Rights Council adopted a resolution for the first time on human rights abuses in Venezuela.[64] 11 Latin American countries proposed the resolution including Mexico, Canada and Argentina.[65] On 23 January 2019, El Tiempo revealed a protest count, showing over 50,000 registered protests in Venezuela since 2013.[66] In 2020, organized protests against Maduro had largely subsided, especially due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Venezuela.[67]

Background

[edit]Bolivarian Revolution

[edit]Venezuela was headed by a series of right-wing governments for years. In 1992, Hugo Chávez formed a group named Revolutionary Bolivarian Movement-200 aiming to take over the government, and attempted a coup d'état.[68][69] Later, another coup was performed while Chávez was in prison. Both coup attempts failed and fighting resulted in around 143–300 deaths.[69] Chávez, after receiving a pardon from president Rafael Caldera, later decided to participate in elections and formed the Movement for the Fifth Republic (MVR) party. He won the 1998 Venezuelan presidential elections. The changes started by Chávez were named the Bolivarian Revolution.

Chávez, an anti-American politician who declared himself a democratic socialist, enacted a series of social reforms aimed at improving quality of life. According to the World Bank, Chávez's social measures reduced poverty from about 49% in 1998 to about 25%. From 1999 to 2012, the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), shows that Venezuela achieved the second highest rate of poverty reduction in the region.[70] The World Bank also explained that Venezuela's economy is "extremely vulnerable" to changes in oil prices since in 2012 "96% of the country's exports and nearly half of its fiscal revenue" relied on oil production. In 1998, a year before Chávez took office, oil was only 77% of Venezuela's exports.[71][72] Under the Chávez government, from 1999 to 2011, monthly inflation rates were high compared to world standards, but were lower than that from 1991 to 1998.[73]

While Chávez was in office, his government was accused of corruption, abuse of the economy for personal gain, propaganda, buying the loyalty of the military, officials involved in drug trade, assisting terrorists such as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, intimidation of the media, and human rights abuses of its citizens.[74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83] Government price controls put in place in 2002 which initially aimed for reducing the prices of basic goods have caused economic problems such as inflation and shortages of basic goods.[84] The murder rate under Chávez's administration also quadrupled during his terms in office leaving Venezuela as one of the most violent countries in the world.[85]

On 5 March 2013, Chávez died of cancer and Nicolás Maduro, who was vice president at the time, took Chávez's place.[86] Throughout the year 2013 and into the year 2014, worries about the troubled economy, increasing crime and corruption increased, which led to the start of anti-government protests.

First demonstrations of 2014

[edit]

Demonstrations against violence in Venezuela began in January 2014,[29] and continued, when former presidential candidate Henrique Capriles shook the hand of President Maduro;[30] this "gesture... cost him support and helped propel" opposition leader Leopoldo López Mendoza to the forefront.[30] According to the Associated Press, well before protests began in the Venezuelan capital city of Caracas, the attempted rape of a young student on a university campus in San Cristóbal, in the western border state of Táchira, led to protests from students "outraged" at "long-standing complaints about deteriorating security under President Nicolas Maduro and his predecessor, the late Hugo Chávez. But what really set them off was the harsh police response to their initial protest, in which several students were detained and allegedly abused, as well as follow-up demonstrations to call for their release". These protests expanded, attracted non-students, and led to more detentions; eventually, other students joined, and the protests spread to Caracas and other cities, with opposition leaders getting involved.[32]

Leopoldo López, a leading figure in the opposition to the government, began leading protests shortly thereafter.[87] During events surrounding the 2002 Venezuelan coup d'état attempt, Lopez "orchestrated the public protests against Chávez and he played a central role in the citizen's arrest of Chavez's interior minister", Ramón Rodríguez Chacín, though he later tried to distance himself from the event.[88]

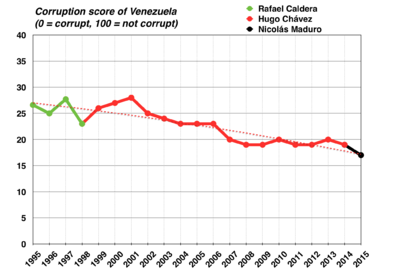

Corruption

[edit]

Source: Transparency International Archived 9 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine

In a 2014 survey by Gallup, nearly 75% of Venezuelans believe corruption is widespread in their government.[89] Leopoldo López has said, "We are fighting a very corrupt authoritarian government that uses all the power, all the money, all the media, all the laws, all the judicial system in order to maintain control."[90]

Corruption in Venezuela is ranked high by world standards. Corruption is difficult to measure reliably, but one well-known measure is the Corruption Perceptions Index, produced annually by a Berlin-based NGO, Transparency International (TNI). Venezuela has been one of the most corrupt countries in TNI surveys since they started in 1995, ranking 38th out of 41 that year[91] and performing very poorly in subsequent years. In 2008, for example, it was 158th out of 180 countries in 2008, the worst in the Americas except Haiti,[92] in 2012, it was one of the 10 most corrupt countries on the index, tying with Burundi, Chad, and Haiti for 165th place out of 176.[93] TNI public opinion data says that most Venezuelans believe the government's effort against corruption is ineffective, that corruption has increased and that government institutions such as the judicial system, parliament, legislature and police are the most corrupt.[94] According to TNI, Venezuela is currently the 18th most corrupt country in the world (160 of 177) and its judicial system has been deemed the most corrupt in the world.[95]

The World Justice Project moreover, ranked Venezuela's government in 99th place worldwide and gave it the worst ranking of any country in Latin America in the 2014 Rule of Law Index.[96] The report says, "Venezuela is the country with the poorest performance of all countries analyzed, showing decreasing trends in the performance of many areas in relation to last year. The country ranks last in the surrender of accounts by the government due to an increasing concentration of executive power and a weakened checks and balances." The report further states that "administrative bodies suffer inefficiencies and lack of transparency...and the judicial system, although relatively accessible, lost positions due to increasing political interference. Another area of concern is the increase in crime and violence, and violations of fundamental rights, particularly the right to freedom of opinion and expression."[82]

Economic problems

[edit]

According to the 2013 Global Misery Index Scores, Venezuela was ranked as the top spot globally with the highest misery index score.[97] In data provided by the CIA, Venezuela had the second highest inflation rate (56.20%) in the world for 2013, only behind the war-torn Syria.[98] The money supply of the hard bolívar in Venezuela also continues to accelerate, possibly helping to fuel more inflation.[99] The Venezuelan government's economic policies, including strict Price controls, led to one of the highest inflation rates in the world with "sporadic hyperinflation",[84] and have caused severe shortages of food and other basic goods.[28] Such policies created by the Venezuelan government have hurt businesses and led to shortages, long queues, and looting.[100]

The Heritage Foundation ranked Venezuela at 175th of 178 in economic freedom and was classified as a "Repressed" economy in its 2014 Index of Economic Freedom report.[101] More than half of those interviewed in a Datos survey held the Maduro government responsible for the country's current economic situation and most thought the country's economic situation would be worse or just as bad in the next 6 months of 2014.[102][103][104] President Maduro has blamed the economic troubles on an alleged "economic war" being waged against his government; specifically, he has placed blame on capitalism and speculation.[54]

An Associated Press report in February 2014 noted that "legions of the sick across the country" were being "neglected by a health care system doctors say is collapsing after years of deterioration". Doctors said it was impossible "to know how many have died, and the government doesn't keep such numbers, just as it hasn't published health statistics since 2010." Health Minister Isabel Iturria refused to give the AP an interview, while a deputy health minister, Nimeny Gutierrez, "denied on state TV that the system is in crisis."[105]

Violent crime

[edit]In Venezuela, a person is murdered every 21 minutes.[106][107] In the first two months of 2014, nearly 3,000 people were murdered – 10% more than in the previous year and 500% higher than when Hugo Chávez first took office.[108] In 2014, Quartz claimed that the high murder rate was due to Venezuela's " growing poverty rate; rampant corruption; high levels of gun ownership; and a failure to punish murderers (91% of the murders go unpunished, according to the Institute for Research on Coexistence and Citizen Security)."[108] InsightCrime attributed the escalating violence to "high levels of corruption, a lack of investment in the police force and weak gun control".[29]

Following the January killing of actress and former Miss Venezuela Mónica Spear and her ex-husband in a roadside robbery in the presence of their five-year-old daughter, who herself was shot in the leg,[29] Venezuela was described by Channel 4 as "one of the most dangerous countries in the world", [29] a country "where crime escalated during the administration of former President Hugo Chávez and killings are common in armed robberies."[29] The Venezuelan Violence Observatory said in March 2014 the country's murder rate was now nearly 80 deaths per 100,000 people, while government statistics put it at 39 deaths per 100,000.[109] The number of those murdered during the previous decade was comparable to the death rate in Iraq during the Iraq War; during some periods, Venezuela had a higher rate of civilian deaths than Iraq, even though the country was at peace.[110] Crime had also affected the economy, according to Jorge Roig, president of the Venezuelan Federation of Chambers of Commerce, who said that many foreign business executives were too scared to travel to Venezuela and that many owners of Venezuelan companies live abroad, with the companies producing less as a result.[111]

The opposition says that crime is the government's fault "for being soft on crime, for politicizing and corrupting institutions such as the judiciary, and for glorifying violence in public discourse", while the government says that "capitalist evils" are to blame, such as drug trafficking and violence in the media.[112]

The United States State Department and the Government of Canada have warned foreign visitors that they may be subjected to robbery, kidnapping for a ransom, or sale to terrorist organizations and murder.[113][114] The United Kingdom's Foreign and Commonwealth Office has advised against all travel within 80 km (50 miles) of the Colombian border in the states of Zulia, Táchira, and Apure.[115]

Elections

[edit]

On 14 April 2013, Nicolas Maduro won the presidential election with 50.6% of the vote, ahead of the 49.1% of candidate Henrique Capriles Radonski, surprisingly close compared to previous polls.[116] Opposition leaders made accusations of fraud shortly after the election[117] and Capriles refused to accept the results, alleging that voters had been coerced to vote for Maduro and claiming election irregularities. The National Electoral Council (CNE), which conducted a post-election audit of a random selection of 54% of the votes, comparing electronic records with paper ballots, claimed to find nothing suspicious.[118][119] Capriles initially called for an audit of the remaining 46% of the votes, asserting that this would show that he had won the election. The CNE agreed to carry out an audit, and planned to do so in May.[118][119] Later Capriles changed his mind, adding demands for a full audit of the electoral registry, and calling the audit process "a joke".[118] Before the government agreed to a full audit of the vote, there were public protests by opponents of Maduro. The crowds were ultimately dispersed by National Guard members using tear gas and rubber bullets.[120] President Maduro responded to the protests by saying, "If you want to try to oust us through a coup, the people and the armed forces will be waiting for you." [121] The clashes resulted in 7 people killed and dozens injured. President Maduro described the protests as a "coup" attempt, and blamed the United States for them. Finally, Capriles told protesters to stop and not play the "government's game," so there would be no more deaths.[122] On 12 June 2013 the results of the partial audit were announced. The CNE certified the initial results and confirmed Maduro's electoral victory.[123]

The opposition's defeat in the 8 December 2013 municipal elections,[124] which it had framed as a 'plebiscite' on Maduro's presidency,[125] ignited an internal debate over strategy. Moderate opposition leaders Henrique Capriles and Henri Falcón argued for 'unity' and dialogue with the government, and attended meetings held by the President to discuss cooperation among the country's mayors and governors.[126][127][128] Other opposition leaders, such as Leopoldo López and Marina Corina Machado, opposed dialogue[129] and called for a new strategy to force an immediate change in the government.[130][131]

Protest violence

[edit]"Colectivos"

[edit]

Militant groups known as "colectivos" attacked protesters and opposition TV staff, sent death threats to journalists, and tear-gassed the Vatican envoy after Hugo Chávez accused these groups of intervening with his government. Colectivos helped assist the government during the protests.[135] Human Rights Watch said that "the government of Venezuela has tolerated and promoted groups of armed civilians," which HRW claims have "intimidated protesters and initiated violent incidents".[136] Socialist International also condemned the impunity that irregular groups have had while attacking protesters.[137] President Maduro has thanked certain groups of motorcyclists for their help against what he views as a "fascist coup d'etat... being waged by the extreme right", but also distanced himself from armed groups, stating that they "had no place in the revolution".[138] On a later occasion, President Maduro issued a condemnation of all violent groups and said a government supporter would go to jail if he performed a crime, just as an opposition supporter would. He said that someone who is violent has no place as a government supporter and thus should leave the pro-government movement immediately.[139]

Some "colectivos" have acted violently against the opposition without impediment from Venezuelan government forces.[140] Vice President of Venezuela, Jorge Arreaza, praised colectivos saying, "If there has been exemplary behavior it has been the behavior of the motorcycle colectivos that are with the Bolivarian revolution."[141] However, on 28 March 2014, Arreaza promised that the government would disarm all irregular armed groups in Venezuela.[142] Colectivos have also been called a "fundamental pillar in the defense of the homeland" by the Venezuelan Prison Minister, Iris Varela.[143][144]

Human Rights Watch reported that government forces "repeatedly allowed" colectivos "to attack protesters, journalists, students, or people they believed to be opponents of the government with security forces just meters away" and that "in some cases, the security forces openly collaborated with the pro-government attackers". Human Rights Watch also stated that they "found compelling evidence of uniformed security forces and pro-government gangs attacking protesters side by side. One report said that government forces aided pro-government civilians that shot protesters with live ammunition.[57]

These groups of guarimberos, fascists and violent [people], and today now other sectors of the country's population as well have gone out on the streets, I call on the UBCh, on the communal councils, on communities, on colectivos: flame that is lit, flame that is extinguished.

Human Rights Watch stated that "Despite credible evidence of crimes carried out by these armed pro-government gangs, high-ranking officials called directly on groups to confront protesters through speeches, interviews, and tweets", further noting that President Nicolas Maduro "on multiple occasions called on civilian groups loyal to the government to 'extinguish the flame' of what he characterized as 'fascist' protesters".[57] The governor of the state of Carabobo, Francisco Ameliach, called on Units of Battle Hugo Chávez (UBCh), a government created civilian group that according to the government is a "tool of the people to defend its conquests, to continue fighting for the expansion of the Venezuelan Revolution". In a tweet, Ameliach asked UBCh to launch a rapid counterattack against protesters saying, "Gringos (Americans) and fascists beware" and that the order would come from the President of the National Assembly, Diosdado Cabello.[57][145][146][147]

Government forces

[edit]Government authorities have used "unlawful force against unarmed protesters and other people in the vicinity of demonstrations". Government agencies involved in the use of unlawful force include the National Guard, the National Police, the Guard of the People, and other government agencies. Some common abuses included "severely beating unarmed individuals, firing live ammunition, rubber bullets, and teargas canisters indiscriminately into crowds, and firing rubber bullets deliberately, at point-blank range, at unarmed individuals, including, in some cases, individuals already in custody". Human Rights Watch said that "Venezuelan security forces repeatedly resorted to force—including lethal force—in situations in which it was wholly unjustified" and that "the use of force occurred in the context of protests that were peaceful, according to victims, eyewitnesses, lawyers, and journalists, who in many instances shared video footage and photographs corroborating their accounts".[57]

Use of firearms

[edit]

Government forces have used firearms to control protests.[149] Amnesty International reported that they had "received reports of the use of pellet guns and tear gas shot directly at protesters at short range and without warning" and that "Such practices violate international standards and have resulted in the death of at least one protester." They also said that "Demonstrators detained by government forces at times have been denied medical care and access to lawyers".[56]

The New York Times reported that a protester was "shot at such close range by a soldier at a protest that his surgeon said he had to remove pieces of the plastic shotgun shell buried in his leg, along with the shards of keys" that were in their pocket at the time. Venezuelan authorities have also been accused of shooting shotguns with "hard plastic buckshot at point-blank range" which allegedly injured a great number of protesters and killed a woman. The woman who was killed was banging a pot outside of her house in protest when her father reported that "soldiers rode up on motorcycles" and that the woman then fell while trying to seek shelter in her home. Witnesses of the incident then said that "a soldier got off his motorcycle, pointed his shotgun at her head and fired". The shot that was fired by the policeman "slammed through her eye socket into her brain". The woman died days before her birthday. Her father said that the soldier who killed her was not arrested.[150] There has also been claims by the Venezuelan Penal Forum accusing authorities that have allegedly attempted to tamper with evidence, covering up that they had shot students.[151]

The article 68 of the Venezuelan Constitution states that "the use of firearms and toxic substances to control peaceful demonstrations is prohibited", and that "the law shall regulate the actions of the police and security control of public order".[152][153]

Use of chemical agents

[edit]

Some demonstrations have been controlled with tear gas and water cannons.[citation needed]

Some mysterious chemical agents were used in Venezuela as well. On 20 March 2014, the appearance of "red gas" first occurred when it was used in San Cristóbal against protesters, with reports that it was CN gas.[154] The first reported use of "green gas" was on 15 February 2014 against demonstrations in Altamira.[155] On 25 April 2014, "green gas" was reportedly used again on protesters in Mérida.[156] Venezuelan-American Ricardo Hausmann, director of the Center for International Development at Harvard made statements that this gas caused protesters to vomit.[157] Some reported that the chemical used was adamsite, a yellow-green arsenical chemical weapon that can cause respiratory distress, nausea and vomiting.[158]

In April 2014, Amnesty International worried about "the use of chemical toxins in high concentrations" by government forces and recommended better training for them.[56]

A study by Mónica Kräuter, a chemist and professor, involved the collection of thousands of tear gas canisters fired by Venezuelan authorities in 2014. She stated that the majority of canisters used the main component CS gas, supplied by Cóndor of Brazil, which meets Geneva Convention requirements. However, 72% of the tear gas used was expired and other canisters produced in Venezuela by Cavim did not show adequate labels or expiration dates. Following the expiration of tear gas, Krauter notes that it "breaks down into cyanide oxide, phosgenes and nitrogens that are extremely dangerous".[159]

In 2017, Amnesty International once again criticized the Bolivarian government's usage of chemical agents, expressing concern of a "red gas" used to suppress protesters in Chacao on 8 April 2017, demanding "clarification of the components of the red tear gas used by state security forces against the opposition demonstrations".[160] Experts stated that all tear gas used by authorities should originally be colorless, noting that the color may be added to provoke or "color" protesters so they can easily be identified and arrested.[161] On 10 April 2017, Venezuelan police fired tear gas at protesters from helicopters flying overhead, resulting with demonstrators running from projectiles to avoid being hit by the canisters.[162]

Abuse of protesters and detainees

[edit]

According to Amnesty International, "torture is commonplace" against protesters by Venezuelan authorities despite Article 46 of the Venezuelan Constitution prohibiting "punishment, torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment".[163] During the protests, there were hundreds of reported cases of torture.[164] In a report titled Punished for Protesting following a March investigation of conduct during the protests, Human Rights Watch said that those who were detained by government authorities were subjected to "severe physical abuse" with some abuses including being beaten "with fists, helmets, and firearms; electric shocks or burns; being forced to squat or kneel, without moving, for hours at a time; being handcuffed to other detainees, sometimes in pairs and others in human chains of dozens of people, for hours at a time; and extended periods of extreme cold or heat." It was also reported that "many victims and family members we spoke with said they believed they might face reprisals if they reported abuses by police, guardsmen, or armed pro-government gangs".[57]

Amnesty International "received reports from detainees who were forced to spend hours on their knees or feet in detention centers". Amnesty International also reported that a student was forced at gunpoint by plainclothes officers to sign a confession to acts he did not commit where his mother explained that "They told him that they would kill him if he didn't sign it, ... He started to cry, but he wouldn't sign it. They then wrapped him in foam sheets and started to hit him with rods and a fire extinguisher. Later, they doused him with gasoline, stating that they would then have evidence to charge him." Amnesty International said that the Human Rights Center at the Andres Bello Catholic University had reported that, "There are two cases that involved electric shocks, two cases that involved pepper gas and another two cases where they were doused with gasoline," she said. "We've found there to be systematic conduct on the part of the state to inflict inhumane treatment on detainees because of similar reports from different days and detention centers."[56]

The New York Times reported that the Penal Forum said that abuses are "continuous and systematic" and that Venezuelan authorities were "widely accused of beating detainees, often severely, with many people saying the security forces then robbed them, stealing cellphones, money and jewelry". In one case, a group of men said that when they were leaving a protest since it turned violent, "soldiers surrounded the car, broke the windows and tossed a tear gas canister inside". A man then said that a soldier "fired a shotgun at him at close range" while in the vehicle. The men were then "pulled from the car and beaten viciously" then one soldier "smashed their hands with the butt of his shotgun, telling them it was punishment for protesters' throwing rocks." The vehicle was then set on fire. One protester said that while detained, soldiers "kicked him over and over again". The protesters he was with "were handcuffed together, threatened with an attack dog, made to crouch for long periods, pepper sprayed and beaten". The protester then said that he was "hit so hard on the head with a soldier's helmet that he heard it crack". A woman also said she was with her daughter when "they were swept up by National Guard soldiers, taken with six other women to a military post and handed over to female soldiers". The women then said that "soldiers beat them, kicked them and threatened to kill them". The women also said that soldiers threatened to rape them, cut their hair and "were released only after being made to sign a paper stating that they had not been mistreated".[150]

Human Rights Watch reported that a man was going home and was attacked by National Guardsman dispersing a group of protesters. He was then hit by rubber bullets the National Guardsmen shot, beat by the National Guardsmen, and then shot in the groin. Another man was detained, shot repeatedly with rubber bullets, beat with rifles and helmets by three National Guardsman and was asked "Who's your president?" Some individuals that were arrested innocently were beaten and forced to repeat that Nicolas Maduro was president.[57]

NTN24 reported from a lawyer that National Guardsmen and individuals with "Cuban accents" in Mérida forced three arrested adolescents to confess to crimes they did not commit and then the adolescents "kneeled and were forced to raise their arms then shot with buckshot throughout their body" during an alleged "target practice".[165][166] NTN24 reported that some protesters were tortured and raped by government forces who detained them during the protests.[167] El Nuevo Herald reported that student protesters had been tortured by government forces in an attempt for the government to make them admit they are part of a plan of foreign individuals to overthrow the Venezuelan government.[168] In Valencia, protesters were dispersed by the National Guard in El Trigál where four students (three men and one woman) were attacked inside of a car while trying to leave the perimeter;[169] the three men were imprisoned and one of them reported being sodomized by one of the officers with a rifle.[170]

In an El Nacional article sharing interviews with protesters who were arrested, individuals explained their experiences in jail. One protester explained how he was placed into a 3 by 2 meter cell with 30 other prisoners where the inmates had to defecate in a bag behind a single curtain. The protester continued explaining how prisoners dealt punishments toward one another and the punishment for "guarimberos" was to be tied and gagged, which would allegedly occur without intervention from the authorities. Other arrested protesters interviewed also explained their fears of being imprisoned with violent criminals.[171]

The director of the Venezuelan Penal Forum, Alfredo Romero, called for both the opposition and the Venezuelan government to listen to the claims of the alleged human rights violations that have not been heard. He also reported that a woman was tortured with electric shocks to her breasts.[172][173] The Venezuelan Penal Forum also reported students being tortured with electric shocks, being beaten, and being threatened of being set on fire after they were doused in gasoline after they were arrested.[174]

Human Rights Watch reported that, "not all of the security force members or justice officials encountered by the victims in these cases participated in the abusive practices. Indeed, in some of the cases ... security officials and doctors in public hospitals had surreptitiously intervened to help them or to ease their suffering". Some National Guardsman assisted detainees that were being held in "incommunicado". It was also reported that "[i]n several cases, doctors and nurses in public hospitals—and even those serving in military clinics—stood up to armed security forces, who wanted to deny medical care to seriously wounded detainees. They insisted detainees receive urgent medical care, in spite of direct threats—interventions that may have saved victims' lives".[57]

On 8 October 2018 the government of Venezuela announced that Fernando Albán Salazar, who was jailed on suspicious attempt of assassination of President Maduro, committed suicide in prison, but friends, relatives, opposition members and NGOs denied the allegation.[175] Alban was arrested on 5 October, at Caracas international airport, when he was coming back from New York, where he had meetings with foreign diplomats attending the United Nations General Assembly.[176]

Government's response to abuses

[edit]The Venezuelan Attorney General's office reported it was conducting, as of the Human Rights Watch report, 145 investigations into alleged human rights abuses, and that 17 security officials had been detained in connection to them. President Maduro and other government officials have acknowledged human rights abuses, but said they were isolated incidents and not part of a larger pattern.[57] When opposition parties asked for a debate about torture in the National Assembly, the Venezuelan government refused, blaming the violence on the opposition saying, "The violent are not us, the violent are in a group of opposition".[177]

El Universal stated that Melvin Collazos of SEBIN, and Jonathan Rodríquez a bodyguard of the Minister of the Interior and Justice Miguel Rodríguez Torres, were in custody after shooting unarmed, fleeing, protesters several times in violation of protocol.[178] President Maduro announced that the personnel who fired at protesters were arrested for their actions.[179]

Arbitrary arrests

[edit]According to Human Rights Watch, Venezuelan government authorities arrested many innocent people. They stated that "the government routinely failed to present credible evidence that these protesters were committing crimes at the time they were arrested, which is a requirement under Venezuelan law when detaining someone without an arrest warrant". They also explained that "Some of the people detained, moreover, were simply in the vicinity of protests but not participating in them. This group of detainees included people who were passing through areas where protests were taking place, or were in public places nearby. Others were detained on private property such as apartment buildings. In every case in which individuals were detained on private property, security forces entered buildings without search orders, often forcing their way in by breaking down doors." One man was in his apartment when government forces fired tear gas into the building. The man went to the courtyard for fresh air and was arrested for no reason after police broke into the apartments.[57]

Violent protests

[edit]

Apart from peaceful demonstrations, an element in some protests includes burning trash, creating barricades and have resulted in violent clashes between the opposition and state authorities. Human Rights Watch said that protesters "who committed acts of violence at protests were a very small minority—usually less than a dozen people out of scores or hundreds of people present". It was reported that barricades were the most common form of protest and that occasional attacks on authorities with Molotov cocktails, rocks and slingshots occurred. In rare instances, homemade mortars were used by protesters. The use of Molotov Cocktails in some cases caught authorities and some government vehicles on fire.[57] President Maduro has stated that some protests "have included arson attacks on government buildings, universities and bus stations".[180]

Barricades

[edit]Throughout the protests, a common tactic that has divided opinions among Venezuelans and the anti-government opposition has been erecting burning street barricades, colloquially known as guarimbas. Initially, these barricades consisted of piles of trash and cardboard set on fire at night, and were easily removed by Venezuelan security forces. Guarimbas have since evolved into "fortress-like structures" of bricks, mattresses, wooden planks and barbed wire guarded by protesters, who "have to resort to guerrilla-style tactics to get a response from the government of President Nicolas Maduro". However, their use is controversial. Critics claim guarimbas, which are primarily erected in residential areas, victimize local residents and businesses and have little political impact.[45] Many opposition protesters argue that guarimbas are also used as a protection against armed groups, and not only as a form of protest.[181]

Demonstrators have used homemade caltrops made of hose pieces and nails, colloquially known in Spanish as "miguelitos" or "chinas", to deflate motorbike tires.[182][183] The government has also condemned their usage.[184] Protesters have cited videos of protests in Ukraine and Egypt as inspiration for their tactics in defending barricades and repelling government forces, such as using common items such as beer bottles, metal tubing, and gasoline to construct fire bombs and mortars, while using bottles filled with paint to block the views of tank and armored riot vehicle drivers. Common protective gear for protesters include motorcycle helmets, construction dust masks, and gloves.[185]

Attacks on public property

[edit]Public property was a target of protester violence. Attacks have been reported by Attorney General Luisa Ortega Diaz on the Public Ministry's headquarters;[186] and by Mayor Ramón Muchacho on the Bank of Venezuela and BBVA Provincial.[187] Many government officials have used social media to announce attacks and document damage. Carabobo state governor Francisco Ameliach used Twitter to report attacks on the United Socialist Party of Venezuela's headquarters in Valencia,[188] as did José David Cabello after an attack by "armed opposition" on the headquarters of the National Integrated Service for the Administration of Customs Duties and Taxes (SENIAT).[189] The wife of the Táchira's governor, Karla Jimenez de Vielma, said the headquarters of the Fundación de la Familia Tachirense had been attacked by "hooligans" and posted photographs of the damage on her Facebook page.[190]

In some attacks, institutions have suffered severe damage. In anger over María Corina Machado being teargassed for trying to enter the National Assembly after having been expelled, some protesters attacked the headquarters of the Ministry of Public Works & Housing. President Maduro said the attack forced the evacuation of workers from the building after it had become "engulfed in flames" with much of the building's equipment destroyed and its windows shattered.[191][192] Two weeks earlier, the Tachira state campus of the National Experimental University of the Armed Forces, a military university that was converted by government decree to a public university, was attacked with molotov cocktails and largely destroyed. The dean, who blamed opposition protesters, highlighted damage to the university's library, technology labs, offices, and buses.[193] A National Guard officer stationed at the university was shot dead days later during a second attack on the campus.[193]

Many vehicles have been destroyed, including those belonging to the national food distribution companies PDVAL[194] and Bicentenario.[195] Electricity Minister Jesse Chacón said 22 vehicles of the company Corpoelec had been burned and that some public property electricity distribution wires were cut down[196] The Land Transport Minister, Haiman El Troudi, reported attacks on the transport system.[197] Some transport routes were temporarily closed, as well as the Caracas subway.[198]

Timeline of events

[edit]

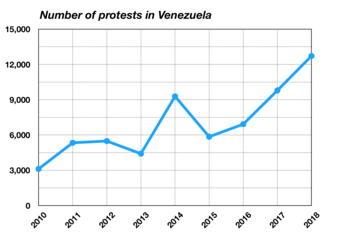

According to the Venezuelan Observatory of Social Conflict (OVCS), 9,286 protests occurred in 2014, the greatest number of protests occurring in Venezuela in decades.[35] The majority of protests, 6,369 demonstrations, occurred during the first six months of 2014 with an average of 35 protests per day.[43] SVCO estimated that 445 protests occurred in January; 2,248 in February; 1,423 in March; 1,131 in April; 633 in May; and 489 in June.[43] The main reason of protest was against President Maduro and the Venezuelan government with 52% of demonstrations and the remaining 42% of protests were due to other difficulties such as labor, utilities, insecurity, education and shortages.[35] Most protesting began in the first week of February, reaching peak numbers in the middle of that month following the call of students and opposition leaders to protest.[43]

The number of protests then declined into mid-2014 only to increase slightly in late 2014 into 2015 following the drop in the price of oil and due to the shortages in Venezuela; with protests denouncing shortages increasing nearly fourfold, from 41 demonstrations in July 2014 to 147 in January 2015.[35] In January 2015, there were 518 protests compared to the 445 in January 2014, with the majority of these protests involving shortages in the country.[199] In the first half of 2015, there were 2,836 protests, with the number of protests dropping from 6,369 in the first half of 2014.[200] Of the 2,836 protests that occurred in the first half of 2015, a little more than 1 of 6 events were demonstrations against shortages.[200] The drop in numbers participating in protests was attributed by analysts to the fear of a government crackdown and Venezuelans being preoccupied with trying to find food due to the shortages.[201] In January and February 2015, European Parliament MEPs condemned the arrest of protesters and began talks of possible targeted sanctions toward the Venezuelan government.[202][203]

In the first two months of 2016, over 1,000 protests occurred along with dozens of lootings, with the SVCO stating that the number of protests were increasing throughout Venezuela.[204] From January to October 2016, 5,772 protests occurred throughout Venezuela with protests for political rights increasing in late 2016.[205]

Following the 2017 Venezuelan constitutional crisis, and the push to ban potential opposition presidential candidate Henrique Capriles from politics for 15 years, protests grew to their most "combative" since they began in 2014.[42] Following the Venezuelan Constituent Assembly election in August 2017, protests subsided for the remainder of the year.

Into 2018, protests increased in numbers following the announcement of a snap election, which eventually resulted with the re-election of Nicolás Maduro. After the election, protests once again began to disappear.[206] According to the Venezuelan Observatory of Social Conflict, by June 2018 more than four thousand protests had occurred in 2018, an average of twenty daily protests, of which eight out of ten were to demand social rights.[207] Other protests that took place the same year were marches against low health works salary and unions protests against hyperinflation in Venezuela, starting in May 2018, and ending in August 2018, with none of their main focal points made with the government.[208] Lawyers, jobless workers and teachers also held strikes throughout the strike movement period, calling for salaries and better wage increases.[209] Protesters formed cacerolazo, human chains, barricades, roadblocks and pickets nationwide.[210]

As a continuation of the 2019 Venezuelan protests, protests continued in 2020, leaving four dead in March. In April, demonstrations took place in at least 100 cities and towns nationwide against food shortages, calling for better conditions and an end to the escalating political crisis.[211] Protesters rallied in late-May for two days, striking against the government's handling of the COVID-19 pandemic and calling on an end to shortages of food, fuel and medicine. Rioting broke out in the next few hours. Police fired tear gas to quell the first wave of demonstrations, but police presence was scarce during the second wave of popular protests prompted by even further tensions, violence, killings, crisis and shortages.[212] Four days of daily protests gained momentum and widespread unrest continued throughout over 105 areas in the country. Thousands participated in protests against late service deliveries and called on a solution to end the electricity, fuel and gas shortages. The wave of demonstrations and protests was the biggest since March. Two people were killed during the second wave of demonstrations.[213]

Domestic reactions

[edit]Government

[edit]

Government allegations

[edit]

In March 2014, the Venezuelan government suggested that the protesters wanted to repeat the 2002 Venezuelan coup d'état attempt.[citation needed] President Maduro also calls the opposition "fascists".[214]

President Maduro has said: "Beginning February 12, we have entered a new period in which the extreme right, unable to win democratically, seeks to win by fear, violence, subterfuge and media manipulation. They are more confident because the US government has always supported them despite their violence."[215] In an op-ed in The New York Times, President Maduro said that the protesters actions had caused several millions of dollars' worth of damage to public property. He continued, saying that the protesters have an undemocratic agenda to overthrow a democratically elected government, and that they are supported by the wealthy while receiving no support from the poor. He also added that crimes by government supporters will never be tolerated and that all perpetrators, no matter who they support, will be held accountable for their actions, and that the government has opened a Human Rights Council to investigate any issues, as "every victim deserves justice".[53] In an interview with The Guardian, President Maduro pointed to the United States' history of backing coups, citing examples such as the 1964 Brazilian coup d'état, 1973 Chilean coup d'état, and 2004 Haitian coup d'état.[52] President Maduro also highlighted whistleblower Edward Snowden's revelations, U.S. state department documents, and 2006 leaked diplomatic cables from the U.S.'s ambassador to Venezuela outlining plans to "'divide', 'isolate' and 'penetrate' the Chávez government" and revealing opposition group funding, some through USAid and the Office of Transition Initiatives, including $5 million earmarked for overt support of opposition political groups in 2014.[52] The United States has denied all involvement in the Venezuelan protests with President Barack Obama saying, "Rather than trying to distract from protests by making false accusations against U.S. diplomats, Venezuela's government should address the people's legitimate grievances".[216][217]

President Maduro also claimed that the government of Panama was interfering with the Venezuelan government.[218] At the same time the Venezuelan government supporters commemorated the first year since the death of President Chávez, the Venezuelan government severed diplomatic relations with Panama. Three days following, the government declared cessation of economic ties with Panama.

During a news conference on 21 February, Maduro once again accused the United States and NATO of trying to overthrow his government through media and claimed that Elias Jaua will be able to prove it.[219] President Maduro asked United States president Barack Obama for help with negotiations.[220] On 22 February during a public speech at the Miraflores Palace, President Maduro spoke out against the media, international artists, and criticized the President of the United States saying, "I invoke Obama and his African American spirit, to give the order to respect Venezuela."[221]

During a press conference on 18 March 2014, President of the National Assembly Diosdado Cabello said that the government accused María Corina Machado of 29 counts of murder due to the deaths resulting from the protests.[222] María Corina Machado was briefly detained when she arrived at Maiquetia Airport on 22 March and was later released that day.[223]

The New York Times editorial board stated that such fears of a coup by President Maduro "appear to be a diversion strategy by a maniacal statesman who is unable to deal with the dismal state of his country's economy and the rapidly deteriorating quality of life despite having the world's largest oil reserves".[224] The allegations made by the government were called by David Smilde of the Washington Office on Latin America as a form of unity, with Smilde saying, "When you talk about conspiracies, it's basically a way of rallying the troops. It's a way of saying 'this is no time for dissent'".[225]

In September 2018, The New York Times reported that "[t]he Trump administration held secret meetings with rebellious military officers from Venezuela over the last year to discuss their plans to overthrow President Nicolás Maduro."[226]

Retired general Hugo Carvajal—the head of Venezuela's military intelligence for ten years during Hugo Chávez's presidency, who served as a National Assembly deputy for the United Socialist Party of Venezuela and was considered a pro-Maduro legislator,[227] "one of the government's most prominent figures"[228]—said that Maduro orders the so-called "spontaneous protests" in his favor abroad, and his partners finance them.[229]

Arrests

[edit]

On 15 February, the father of Leopoldo Lopez said "They are looking for Leopoldo, my son, but in a very civilized way" after his house was searched through by the government.[230] The next day, Popular Will leader Leopoldo Lopez announced that he would turn himself in to the Venezuelan government after one more protest saying, "I haven't committed any crime. If there is a decision to legally throw me in jail I'll submit myself to this persecution."[231] On 17 February, armed government intelligence personnel illegally forced their way into the headquarters of Popular Will in Caracas and held individuals that were inside at gunpoint.[232] On 18 February, Lopez explained during his speech how he could have left the country, but "stayed to fight for the oppressed people in Venezuela".[233] Lopez surrendered to police after giving his speech and was transferred to the Palacio de Justicia in Caracas where his hearing was postponed until the next day.[234]

Human Rights Watch demanded the immediate release of Leopoldo Lopez after his arrest saying, "The arrest of Leopoldo López is an atrocious violation of one of the most basic principles of due process: you cannot imprison someone without evidence linking him with a crime".[235][236]

During the last few weeks of March, the government began making more accusations and arresting opposition leaders. Opposition mayor Vicencio Scarano Spisso was tried and sentenced to ten and a half months of jail for failing to comply with a court order to take down barricades in his municipality which resulted in various deaths and injuries in the previous days.[237] Adán Chávez, older brother of Hugo Chávez, joined the government's effort of criticizing opposition mayors who have supported the protest actions, stating that they "could end up like Scarano and Ceballos" by being charged for various cases.[238] On 27 February, the government issued an arrest warrant for Carlos Vecchio, a leader of Popular Will on various charges.[239]

On 25 March, President Maduro announced that three Venezuelan Air Force generals were arrested for allegedly planning a "coup" against the government and in support for the protests and will be charged accordingly.[240] On 29 April, Captain Juan Caguaripano of the Bolivarian National Guard criticized the Venezuelan government in a YouTube video. He said that "As a national guard member who loves this country and is worried about our future and our children". He continued saying that, "There are sufficient reasons to demand the resignation of the president, to free the political prisoners" and said that the government conducted a "fratricidal war". This video was posted days after Scott was accused of plotting a coup against the government "joining three generals from the air force and another captain of the national guard already accused of plotting against the state".[241]

225 Venezuelan military officers rejected the allegations against the three air force generals stating that to bring them before a military court "would be violating their constitutional rights, as it is essential first to submit a preliminary hearing" and asked the National Guard "to be limited to fulfill its functions under articles 320, 328 and 329 of the Constitution and cease their illegal activities repression of public order".[242] The allegations against the air force generals were also seen by former Venezuelan officials and commanders as a "media maneuver" to gain support from UNASUR since President Maduro timed it for the meeting and was not able to give details.[243]

Law enforcement actions

[edit]

Personnel from the Bolivarian National Police and the Venezuelan National Guard were also seen firing weapons and bombs on buildings where opposition protesters were gathered.[244] During a press conference, Minister of the Interior and Justice Miguel Rodriguez Torres denied allegations of Cuban special forces known as the "Black Wasps" of the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces assisting the Venezuelan government with protests saying that the only Cubans in Venezuela were helping with medicine and sports.[245]

The allegations that members of the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces were in Venezuela began when many people reported images of a military transport plane deploying uniformed soldiers alleged to be Cuban.[246]

In late March 2017, three officers from the National Bolivarian Armed Forces of Venezuela requested political asylum in Colombia becoming the first documented case of desertion since Maduro came to power.[247]

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights OHCHR issued a report in July 2018 mentioning the excessive arbitrary arrests and detentions by the Venezuelan intelligence and security forces since July 2017.[248] The report says that since 2014. There has been more than 12,000 arbitrarily arrests. From August 2017 to May 2018 alone at least 570 people, including 35 children, have been detained.[249] Venezuelan security forces have summarily executed many of anti- government protesters.[248]

Resolution 8610

[edit]On 27 January 2015, the Venezuelan Minister of Defense, Vladimir Padrino López, signed Resolution 8610 which stated that the "use of potentially lethal force, along with the firearm or another potentially lethal weapon" could be used as a last resort by the Venezuelan armed forces "to prevent disorders, support the legitimately constituted authority and reject any aggression, facing it immediately and the necessary means".[250] The resolution conflicted with Article 68 of the Venezuelan Constitution that states, "the use of firearms and toxic substances to control peaceful demonstrations is prohibited. The law shall regulate the actions of the police and security in the control of public order".[250]

The resolution caused outrage among some Venezuelans which resulted in protests against Resolution 8610, especially after the death of 14-year-old Kluiberth Roa Nunez, which had protests days after his death numbering in the thousands.[251][252][253] Students, academics and human rights groups condemned the resolution.[254] International entities had expressed concern with Resolution 8610 as well, including the Government of Canada which stated that it was "concerned by the decision of the Government of Venezuela to authorize the use of deadly force against demonstrators" while the European Parliament demanded the repeal of the resolution entirely.[255][256]

Days after the introduction of the resolution, Padrino López stated that critics "decontextualized" the decree calling it "the most beautiful document of profound respect for human rights to life and even the protesters".[257] On 7 March 2015, Padrino López later announced that the Venezuelan government was expanding on Resolution 8610 to give more detailed explanations and that the decree "should be regulated and reviewed".[258]

Opposition

[edit]Opposition allegations

[edit]

In an op-ed for The New York Times titled "Venezuela's Failing State," Lopez lamented "from the Ramo Verde military prison outside Caracas" that for the past fifteen years, "the definition of 'intolerable' in this country has declined by degrees until, to our dismay, we found ourselves with one of the highest murder rates in the Western Hemisphere, a 57 percent inflation rate and a scarcity of basic goods unprecedented outside of wartime." The economic devastation, he added, "is matched by an equally oppressive political climate. Since student protests began on Feb. 4, more than 1,500 protesters have been detained, more than 30 have been killed, and more than 50 people have reported that they were tortured while in police custody," thus exposing "the depth of this government's criminalization of dissent." Addressing his incarceration, López recounted that on 12 February, he had "urged Venezuelans to exercise their legal rights to protest and free speech – but to do so peacefully and without violence. Three people were shot and killed that day. An analysis of video by the news organization Últimas Noticias determined that shots were fired from the direction of plainclothes military troops." Yet after the protest, "President Nicolás Maduro personally ordered my arrest on charges of murder, arson and terrorism.... To this day, no evidence of any kind has been presented."[61]

The student leader at University of the Andes marched with protesters and delivered a document to the Cuban Embassy saying, "Let's go to the Cuban Embassy to ask them to stop Cuban interference in Venezuela. We know for a fact that Cubans are in the barracks' and Miraflores giving instructions to suppress the people."[259][260]

The opposition demonstrations that followed have been called by some as "Middle Class Protests".[261] However, some lower class Venezuelans told student protesters visiting them that they also want to protest against the "worsening food shortages, crippling inflation and unchecked violent crime" but are afraid to since pro-government groups known as "colectivos" had "violently suppressed" demonstrations and had killed some opposition protesters too.[262]

Public opinion

[edit]Public support of protests

[edit]Since the outset of the protests, peaceful daytime demonstrations advocating for policy changes and "redress of misgovernment" have received widespread support among the public.[263] However, calls for regime change have been met with minimal backing while opposition leaders have struggled to win over politically unaffiliated Venezuelans and members of the lower classes.

Support by the poor

[edit]Protests like this by the poor are really new. The opposition always claimed they existed before, but when you talked to the demonstrators, they were all middle class. But now, it is the poorest who are suffering the most.

The majority of protests were originally limited to more affluent areas of major cities with many working-class citizens thinking that the protests were unrepresentative of them and not working in their interests.[263] This was especially evident in the capital Caracas, where in the wealthier east side of the city, protests widely disrupted daily activities, while life in the poorer west side of the city—hit especially hard by the country's economic struggles— largely continued as normal.[51] The New York Times describes this "split personality" as representative of a long-standing class divide within the country and a potentially crippling fault within the anti-government movement, recognized both by opposition leaders and President Maduro.[49] Later in the protests, however, many in Venezuela's slums that are seen as "bulwarks of [government] support" thanks to social welfare programs, supported the protesters due to frustrations over crime, shortages, and inflation[264] and increasingly began to protest and loot as the situation in Venezuela continuously deteriorated.[50]

In some poor neighborhoods like Petare in western Caracas, residents that had benefitted from such government programs, joined protests against inflation, high murder rates and shortages.[265] Demonstrations in some poor communities remain rare, partially out of fear of armed colectivos acting as community enforcers and distrust of opposition leaders. An Associated Press investigation that followed two students encouraging anti-government support in poor districts found much discontent among the lower classes, but those Venezuelans were generally more worried about possibly losing pensions, subsidies, education, and healthcare if the opposition were to gain power, and many stated they felt leaders on both sides were only concerned with their own interests and ambitions.[264] The Guardian has also sought out viewpoints from the Venezuelan public. Respondents reiterated many of the core protest themes for their protester support: struggles with shortages in basic goods; crime; mismanagement of oil revenue; international travel struggles caused by difficulties in buying airline tickets and the "bureaucratic nightmare" of buying foreign currency; and frustration over the government's rhetoric regarding the alleged "far-right" nature of the opposition.[266] Others offered a variety of reasons for not joining the protests, including: support for the government due to improvements in education, healthcare, and public transportation; pessimism over whether Maduro's ouster would lead to meaningful changes; and the belief that a capitalist model would be no more effective than a socialist model in a corrupt government system.[267]

Protest coverage

[edit]Public support for the protests has also been affected by media coverage. Some outlets have downplayed, and sometimes ignored, the larger daytime protests, allowing the protest movement to be defined by its "tiny, violent guarimbero clique," whose radicalism undermines support for the mainline opposition and seemingly reinforces the government's narrative of "fascists" working to overthrow the government[263] in what Maduro described as a "slow motion coup".[51] An activist belonging to the Justice First party said, "Media censorship means people here only know the government version that spoiled rich kids are burning down wealthy parts of Caracas to foment a coup," creating a disconnect between opposition leaders and working-class Venezuelans that keeps protest support from spreading.[51]

Analysis of support

[edit]Some Venezuelans contend that the protests—seen as "rich people trying to get back lost economic perks"—have only served to unite the poor in defense of the revolution.[51] Analysts such as Steve Ellner, a political science professor at the University of the East in Puerto La Cruz, have expressed doubt over the protests' ultimate effectiveness if the opposition cannot create broader social mobilization.[51] Eric Olson, associate director for Latin America at the Woodrow Wilson International Center, said disruption caused by protesters had allowed Maduro to use the "greedy economic class" as a scapegoat, which has been an effective narrative for gaining support because people "are more inclined to believe conspiracy theories of price gouging than the intricacies of underlining economic policies".[51]

Poll and survey data

[edit]

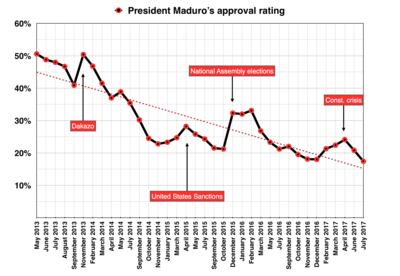

Sources: Datanálisis

Luis Vicente León, the president of Datanálisis, announced on 6 April his findings that 70% who supported the protests at their start turned to 63% of Venezuelan rejecting the form of protests. He also announced that the results of his latest opinion studies showed President Maduro at between 42% and 45% popularity, while no opposition leader surpassed 40%.[268] Another Datanálisis poll released on 5 May found that 79.5% of Venezuelans evaluated the country's situation as "negative". Maduro's disapproval rating had risen to 59.2%, up from 44.6% in November 2013. It also found that only 9.6% of the population would support the re-election of Maduro in 2019. The poll revealed that the Democratic Unity Roundtable had an approval rating of 39.6% compared to 50% of those who disapproved it; while the ruling United Socialist Party of Venezuela had a 37.4% approval rating, and a disapproval rating of 55%.[269]

In a poll released on 5 May 2015, Datanálisis found that 77% of respondents did not intend to participate in peaceful protests, while 88% would not participate in protests involving barricades. León attributed this to the criminalization of the protests, fears of government repression, and frustration over the protests' goals not being achieved. The poll also found that 70% would participate in upcoming parliamentary elections—a possible "exhaust valve" for channeling popular discontent—but León noted this represented weakened participation and that Venezuelans were preoccupied with economic and social issues.[270]

Media

[edit]Domestic media

[edit]

The Inter American Press Association protested against the "official censorship" of media by the government in Venezuela which included blocking the internet, banning channels, revoking foreign media credentials, harassing reporters and limiting resources for newspapers.[271] The Association of Foreign News Correspondents in Venezuela also accused the government of assault, abuse, harassment, threats and robberies of reporters.[272]

Media coverage in Venezuela has been limited by the government; "anti-government television stations such as RCTV and Globovision had their licenses revoked and were forced to undergo changes in ownership, respectively."[273] The government has, according to the opposition, "a powerful structure of radio stations, television stations and newspapers to have a communicational hegemony with their public funds" and does not provide reliable information from the Central Bank about the economy or any statistics about crime to journalists.[274]

On 15 March 2014, President of the National Assembly Diosdado Cabello announced a new commission called the "Truth Commission" whose establishment was ordered by the president in order to show videos and images of "where fascism is".[275]

Attacks on reporters

[edit]The Association of Foreign News Correspondents in Venezuela accused the government of assaulting reporters.[272] The National Union of Journalists (SNTP) in Venezuela has said there has been at least 181 attacks on journalists in the first few months of 2014 and that there has been "82 cases of harassment, 40 physical assaults, 35 robberies or destruction of the work material, 23 arrests and a bullet wound" and that at least 20 attacks were performed by "colectivos".[276][277][278][279] The National Institute of Journalists (CNP) stated that 262 attacks on the press occurred between February and June 2014.[280] According to El Nacional, the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (SEBIN) had raided facilities of reporters and human rights defenders several times.[281] It was also stated that SEBIN occasionally intimidated reporters by following them in unmarked vehicles where SEBIN personnel would "watch their homes and offices, the public places like bakeries and restaurants, and would send them text messages to their cell phones".[281]

Foreign media

[edit]According to The Washington Post, the Venezuelan protests in 2014 were overlooked by the United States media by the crisis in Ukraine.[282] The Post performed LexisNexis searches of the topics in Venezuela and Ukraine within news stories from The Washington Post and The New York Times and found that the Ukrainian topics were nearly doubled compared to the Venezuelan topics.[282]

The Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights also said that, "Documenting the protests has been a challenge for members of the media and NGO's as the government has stifled the flow of information" and that "Journalists have been threatened and arrested, and had their equipment confiscated or had materials erased from their equipment."[283] Those reporting the protests feel threatened by President Maduro who has created "an increasingly asphyxiating climate" for them.[284] Television stations in Venezuela have hardly displayed live coverage of protests and had resulted in many opposition viewers moving to CNN in 2014.[285]

Years later on 14 February 2017, President Maduro ordered cable providers to take CNN en Español off the air, days after CNN aired an investigation into the alleged fraudulent issuing of Venezuelan passports and visas. The news story revealed a confidential intelligence document that links Venezuelan Vice President Tareck El Aissami to 173 Venezuelan passports and IDs issued to individuals from the Middle East, including people connected to the terrorist group Hezbollah.[286][287]

Censorship

[edit]

The secretary general of Reporters Without Borders said in a letter to President Maduro condemning the censorship by the Venezuelan government and responding to Delcy Rodríguez who denied attacks on journalists by saying, "I can assure you that the cases documented by Reporters Without Borders and other NGOs such as Espacio Público, IPYS and Human Rights Watch were not imagined."[288] According to Spanish newspaper El País, National Telecommunications Commission of Venezuela (Conatel) warned Internet service providers in Venezuela that they, "must comply without delay with orders to block websites with content contrary to the interests of the Government" in order to prevent "destabilization and unrest".[289] It was also reported by El País that there will be possible automations of DirecTV, CANTV, Movistar and possible regulation of YouTube and Twitter.[289]

Internet censorship

[edit]In 2014, there were mixed reports of internet censorship. It was reported that Internet access was unavailable in San Cristóbal, Táchira for up to about half a million citizens from an alleged blockage of service by the government.[290][291][292][293][294] This happened after President Maduro threatened Táchira that he would "go all in" and that citizens "would be surprised".[295] Internet access was reported to be available again one day and a half later.[296]

Social media applications such as Twitter[297][298] and Zello[299][300] are censored by the Venezuelan government as well.

State media censorship

[edit]During her speech at the National Assembly, María Corina Machado had the camera taken off of her while she was presenting those who were killed and while criticizing Luisa Ortega Díaz saying, "I heard the testimony of Juan Manuel Carrasco who was raped and tortured and the Attorney General of this country has the inhuman condition to deny and even mock".[301]

Censoring of domestic media

[edit]One threat a journalist faced was a note placed on her car by someone belonging to the Tupamaros. The note was titled, "Operation Defense of the Socialist Revolution, Anti-Imperialist, and Madurista Chavista" said that her actions "promote destabilizing actions of fascist groups and stateless persons who seek to overthrow the legitimate government of President Nicolas Maduro, probably financed and paid by the squalid and bourgeois right have burned the country". They gave the reporter and ultimatum saying they knew where she and her family stayed telling her to "immediately stop communication" or she would suffer consequences in order to "enforce the Constitution and keep alive the legacy of our supreme commander and eternal Hugo Chavez".[302]

A cameraman who resigned from Globovisión shared images that were censored by the news agency showing National Guard troops and colectivos working together during the protests.[303]

Censoring of foreign media

[edit]The Colombian news channel NTN24 was taken off the air by CONATEL (the Venezuelan government agency appointed for the regulation, supervision and control over telecommunications) for "promoting violence".[304] President Maduro also denounced the Agence France-Presse (AFP) for manipulating information about the protests.[305]

On 19 April 2017 during the Mother of All Marches, TN's satellite signal was censored after showing live coverage of the protests. El Tiempo of Colombia was also censored in the country during the day's protests.[306]

Social media

[edit]

Social media is an essential tool for Venezuelans to show the news in the streets, which contradicts most official news from the government and most stories have to be compiled together from cell phone videos on small websites.[307] The popularity of social media to some Venezuelans is due to a lack of trust, supposed propaganda from state owned media and alleged "self-censorship" that private media now uses in order to please the government.[273] According to Mashable, Twitter is very popular in Venezuela and according to an opposition figure, "Venezuela is a dictatorship, and the only free media is Twitter,"[308] Protesters use Twitter since "traditional media" has been unable to cover the protests and so that, "the international community can notice what's happening and help us spread the word in every corner,"[308] However, the government has been accused of using Twitter as a propaganda tool when it allegedly "purchased followers, created fake accounts to boost pro-government hashtags, and hired a group of users to harass critics" and claiming protesters were "fascists" that were trying to commit a "coup d'état".[308]

False media

[edit]"The social networks have come to be an alternative media," states Tarek Yorde, a Caracas-based political analyst. "But both sides, the government and opposition, use them to broadcast false information."[273] Some photographs, often outdated or from protests in various countries around the world including Syria, Chile and Singapore, have been circulated by the opposition through social media to foment dissent.[309][310] In an interview with The Nation, Venezuelan writer and member of the Venezuelan Council of State Luis Britto García referenced such photographs as evidence of the opposition's campaign to falsely portray the protests as having widespread student support when the protests instead involve, as he claimed, only a few hundred students in a country with 9.5 million of them.[311]

Usage of false media also applies to the government when President of the National Assembly, Diosdado Cabello, shared a photo on a VTV program showing an alleged "gun collection" at the home of Ángel Vivas, when it was really a photo taken from an airsoft gun website.[312][313][314][315] Minister of Tourism, Andrés Izarra, also used old images of crowded ferries from August 2013 trying to indicate that life is back to normal in Venezuela and a massive mobilization of ferries are on their way to Margarita Island.[316][317][318] Student protesters contested the statement, saying there is no Carnaval celebrations on the island and that "here there is nothing to celebrate; Venezuela is mourning".[319] President Maduro allegedly played a video, edited specifically in order to accuse mayor of Chacao of promoting barricades.[320]

International reactions

[edit]

See also

[edit]- 2013 Venezuelan presidential election protests

- La Salida

- Spring (political terminology)

- Protests against Daniel Ortega

- States of emergency in Venezuela

- List of protests in the 21st century

References