Jewish principles of faith

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Jewish philosophy |

|---|

|

The formulation of principles of faith that are universally recognized by all branches of Judaism remains undefined. There is no central authority in Judaism in existence today - although the Sanhedrin, the supreme Jewish religious court, would fulfill this role if it were re-established. Instead, Judaism's principles of faith remain debated by the rabbis based on their understanding of the sacred writings, laws, and traditions, which collectively shape its theological and ethical framework. The most accepted version in extent is the opinion of Maimonides.

Maimonides collection of fundamentals is found in his Commentary to the Mishna. He stresses the importance in believing that there is one single, omniscient, transcendent, non-compound God, who created the universe, and continues to monitor all creation to allow for eventual reward or punishment. Part of the list is the idea that God created the world from nothingness, to the coming of Mashiach and resurrection. Also included is the principle that God revealed his laws and 613 commandments to the Jewish people in the form of the Written and Oral Torah. In Rabbinic Judaism, the Torah consists of both the written Torah (Pentateuch) and a tradition of oral law, much of it later codified in sacred writings (see: Mishna, Talmud).

Traditionally, the practice of Judaism has been devoted to the study of Torah and observance of its laws and commandments. In normative Judaism, the Torah, and hence Jewish law itself, is unchanging, but interpretation of the law is more open. It is considered a mitzvah (commandment) to study and understand the law.

Conception of God

[edit]Monotheism

[edit]Judaism is based on a strict monotheism, and a belief in one single, indivisible, non-compound God. The Shema Yisrael. This is illustrated in what is considered by some to be the Jewish moto, encapsulating the monotheistic nature of Judaism:[1] "Hear, O Israel: The LORD is our God; the LORD is one."[2]

"Judaism emphatically rejects any concept of plurality with respect to God",[3] explicitly rejecting polytheism, dualism, and trinitarianism, which are "incompatible with monotheism as Judaism understands it".[1] The unity of God is stated many times in Jewish tradition. It is the second of Maimonides's 13 principles of faith; Maimonides wrote that, "This God is One, not two or more than two, but One whose unity is different from all other unities that there are. He is not one as a genus, which contains many species, is one. Nor is He one as a body, containing parts and dimensions, is one. But His is a unity that which there is no other anywhere" (Yad, Yesode Ha-Torah 1:7).[1]

In Jewish tradition, dualistic and trinitarian conceptions of God are generally referred to as Shituf ("partnership"), incorrect, but not idolatrous.[4]

God is the creator of the universe

[edit]Traditionally, Jews believe that God is the creator of the universe. Different sects of Jews view this in different ways. For example, some strictly-Orthodox groups reject the concept of evolution and believe the earth to be only a few thousands years old. Other groups of Orthodox and non-Orthodox Jews do not believe in a literal interpretation of the Genesis creation narrative, and according to that view, Judaism is not in contradiction to the scientific model that states that the age of the universe is around 13.77 billion years old.[5] Norbert M. Samuelson writes the "question of dating the universe has never been a problem of Jewish philosophy, ultimately because that philosophy has never taken the literal meaning of the Bible to be its revealed, true meaning".[6]

Moses Maimonides (12th century) wrote that "by virtue of the existence of the Creator, everything exists"[7] and that "time itself is part of creation" and therefore, "when God is described as existing before the creation of the universe, the notion of time should not be understood in its normal sense".[8] The 15th-century Jewish philosopher Joseph Albo argued similarly in his Ikkarim that there are two types of time: "Measured time which depends on motion, and time in the abstract", the second of which has no origin and is "the infinite space of time before the universe was created". Albo argued that "although it is difficult to conceive of God existing in such a duration, it is likewise difficult to imagine God outside space". Other Jewish writers have come to different conclusions, such as 13th-century scholar Bahya ben Asher, 16th-century scholar Moses Almosnino, and the 18th-century Hasidic teacher Nahman of Bratslav, who expressed a view - similar to that expressed by the Christian Neo-Platonic writer Boethius - that God "lives in the eternal present" and transcends or is above all time.[9]

Nature of God

[edit]The Jewish view is that God is eternal, with "neither beginning nor end", a principle stated in a number of Biblical passages. The rabbis taught a "quite literally ... down-to-earth" view of the eternalness of God: That "God is eternal, but it is not given to man to explore the full meaning of this idea", and so, "one cannot, therefore, expect to find in the rabbinic literature anything like a detailed examination of what is meant by divine eternity". A famous Mishnah statement on attempts to "pierce the veil" is this: "Whoever reflects on four things it were better for him that he had not come into the world: "what is above? what is beneath? what is before? and what is after?"[10]

Various Jewish thinkers, however, have proposed a "finite God", sometimes in response to the problem of evil and ideas about free will. Louis Jacobs writes that modern Jewish thinkers such as Levi Olan, echoing some classical Jewish writers such as the 14th-century Talmudist Gersonides have "thought of God as limited by His own nature so that while He is infinite in some respects he is finite in others", referencing the idea, present in classical sources, that "there is a primal formless material co-existent with God from all eternity upon which God has to work, and that God only knows the future in a general sense, but not how individual men will exercise their choice".[11] On the topic of omniscience and free will, Jacobs writes that in the medieval period, three views were put forth: Maimonides, who wrote that God had foreknowledge and man is free; Gersonides, who wrote that man is free and consequently God does not have complete knowledge, and Hasdai Crescas, who wrote in Or Adonai that God has complete foreknowledge and consequently man is not really free.[11]

Several Jewish writers have dealt with the issue of theodicy: whether and how God is all-powerful and all-good, given the existence of evil in the world, particularly the Holocaust. Jon D. Levenson argues that omnipotence doctrine fails to "give due regard to "'the formidability and resilience of the forces counteracting creation" (such as the primordial state of chaos existing before creation) and "leads to a neglect of the role of humanity in forming and stating the world order.[12] Hans Jonas proposed a "tentative myth" that "God 'chose' in the beginning to give God's self 'over to the chance and risk and endless variety of becoming, entering into the adventure of space in time". Jonas expressed the view that "God does not create the world by fiat (although God does create the world), but leads it by beckoning it into novel possibilities of becoming. Jonas, who was influenced by the Holocaust experience, believed that God is omnipresent, but not "in all respects non-temporal, impassible, immutable, and unqualified omnipotent".[12]

Traditionlly, Judaism views God as a personal god. This is shown in the Jewish liturgy, such as in the Adon Olam hymn, which includes a "confident affirmation" that "He is my God, my living God...Who hears and answers".[13] Edward Kessler writes that Hebrew Bible "portrays an encounter with a God who cares passionately and who addresses humanity in the quiet moments of its existence".[14] British chief rabbi Jonathan Sacks suggests that God "is not distant in time or detached, but passionately engaged and present".[14] The predicate 'personal' as applied to God does not mean that God is corporeal or anthropomorphic, views which Judaism has always rejected; rather, "personality" refers not to physicality, but to "inner essence, psychical, rational, and moral".[13] Although most Jews believe that "God can be experienced", it is understood that "God cannot be understood" because "God is utterly unlike humankind" (as shown in God's response to Moses when Moses asked for God's name: "I Am that I Am"); all anthropomorphic statements about God "are understood as linguistic metaphors; otherwise, it would be impossible to talk about God at all".[14]

Although the dominant strain in Judaism is that God is personal, there is an "alternate stream of tradition exemplified by ... Maimonides", who, along with several other Jewish philosophers, rejected the idea of a personal God.[14] This reflected his belief in negative theology: that God can only be described by what God is not.[14] Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan, who developed Reconstructionist Judaism and taught at the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary of America, also rejected the idea of a personal God. Kaplan instead thought of God "as a force, like gravity, built into the very structure of the universe", believing that "since the universe is constructed to enable us to gain personal happiness and communal solidarity when we act morally, it follows that there is a moral force in the universe; this force is what the Constructionists mean by God", although some Reconstructionists do believe in a personal God.[15] According to Joseph Telushkin and Morris N. Kertzer, Kaplan's "rationalist rejection of the traditional Jewish understanding of God exerted a powerful influence" on many Conservative and Reform rabbis, influencing many to stop believing in a personal God".[16] According to the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life's 2008 U.S. Religious Landscape Survey, Americans who identify as Jewish by religion are twice as likely to favor ideas of God as "an impersonal force" over the idea that "God is a person with whom people can have a relationship".[17]

Sole Devotion to the Creator

[edit]Within Judaism, the essence of worship is deeply rooted in the belief of monotheism, emphasizing the exclusive devotion to the Creator. This principle dictates that worship and reverence should be directed solely towards God, as articulated by Maimonides' fifth principle of faith. According to this belief, no entity, aside from the Creator, is deemed worthy of worship.[18]

Revelation

[edit]Scripture

[edit]The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh is the Jewish scriptural canon and central source of Jewish law. The word is an acronym formed from the initial Hebrew letters of the three traditional subdivisions of the Tanakh: The Torah ("Teaching", also known as the Five Books of Moses or Pentateuch), the Nevi'im ("Prophets") and the Ketuvim ("Writings").[19] The Tanakh contains 24 books in all; its authoritative version is the Masoretic Text. Traditionally, the text of the Tanakh was said to have been finalized at the Council of Jamnia in 70 CE, although this is uncertain.[19] In Judaism, the term "Torah" refers not only to the Five Books of Moses, but also to all of the Jewish scriptures (the whole of Tanakh), and the ethical and moral instructions of the rabbis (the Oral Torah).[20]

In addition to the Tanakh, there are two further textual traditions in Judaism: Mishnah (tractates expounding on Jewish law) and the Talmud (commentary of Misneh and Torah). These are both codifications and redactions of the Jewish oral traditions and major works in Rabbinic Judaism.[20]

The Talmud consists of the Babylonian Talmud (produced in Babylon around 600 CE) and the Jerusalem Talmud (produced in the Land of Israel circa 400 CE). The Babylonian Talmud is the more extensive of the two and is considered the more important.[21] The Talmud is a re-presentation of the Torah through "sustained analysis and argument" with "unfolding dialogue and contention" between rabbinic sages. The Talmud consists of the Mishnah (a legal code) and the Gemara (Aramaic for "learning"), an analysis and commentary to that code.[21] Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz writes that "If the Bible is the cornerstone of Judaism, then the Talmud is the central pillar ... No other work has had a comparable influence on the theory and practice of Jewish life, shaping influence on the theory and practice of Jewish life" and states:[22]

The Talmud is the repository of thousands of years of Jewish wisdom, and the oral law, which is as ancient and significant as the written law (the Torah) finds expression therein. It is a conglomerate of law, legend, and philosophy, a blend of unique logic and shrewd pragmatism, of history and science, anecdotes and humor... Although its main objective is to interpret and comment on a book of law, it is, simultaneously, a work of art that goes beyond legislation and its practical application. And although the Talmud is, to this day, the primary source of Jewish law, it cannot be cited as an authority for purposes of ruling...

Though based on the principles of tradition and the transmission of authority from generation to generation, it is unparalleled in its eagerness to question and reexamine convention and accepted views and to root out underlying causes. The talmudic method of discussion and demonstration tries to approximate mathematical precision, but without having recourse to mathematical or logical symbols.

...the Talmud is the embodiment of the great concept of mitzvat talmud Torah - the positive religious duty of studying Torah, of acquiring learning and wisdom, study which is its own end and reward.[22]

Moses and the Torah

[edit]Orthodox and Conservative Jews hold that the prophecy of Moses is the "Av" (senior) of all other prophets, even of those who were before and after him. This belief was expressed by Maimonides, who wrote that "Moses was superior to all prophets, whether they preceded him or arose afterwards. Moses attained the highest possible human level. He perceived God to a degree surpassing every human that ever existed... God spoke to all other prophets through an intermediary. Moses alone did not need this; this is what the Torah means when God says, "Mouth to mouth, I will speak to him". The great Jewish philosopher Philo understands this type of prophecy to be an extraordinarily high level of philosophical understanding, which had been reached by Moses and which enabled him to write the Torah through his own rational deduction of natural law. Maimonides describes a similar concept of prophecy, since a voice that did not originate from a body cannot exist, the understanding of Moses was based on his lofty philosophical understandings.[23] However, this does not imply that the text of the Torah should be understood literally, as according to Karaism. Rabbinic tradition maintains that God conveyed not only the words of the Torah, but the meaning of the Torah. God gave rules as to how the laws were to be understood and implemented, and these were passed down as an oral tradition. This oral law was passed down from generation to generation and ultimately written down almost 2,000 years later in the Mishna and the two Talmuds.

For Reform Jews, the prophecy of Moses was not the highest degree of prophecy; rather it was the first in a long chain of progressive revelations in which mankind gradually began to understand the will of God better and better. As such, they maintain that the laws of Moses are no longer binding, and it is today's generation that must assess what God wants of them. This principle is also rejected by most Reconstructionist Jews, but for a different reason; most posit that God is not a being with a will; thus, they maintain that no will can be revealed.[24]

The origin of the Torah

[edit]The Torah is composed of 5 books called in English Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. They chronicle the history of the Hebrews and also contain the commandments that Jews are to follow.

Rabbinic Judaism holds that the Torah extant today is the same one that was given to Moses by God on Mount Sinai. Maimonides explains: "We do not know exactly how the Torah was transmitted to Moses. But when it was transmitted, Moses merely wrote it down like a secretary taking dictation...[Thus] every verse in the Torah is equally holy, as they all originate from God, and are all part of God's Torah, which is perfect, holy and true."

Haredi Jews generally believe that the Torah today is no different from what was received from God to Moses, with only the most minor of scribal errors. They note that the Masoretes (7th to 10th centuries) compared all known Torah variations in order to create a definitive text.

However, even according to this position that the scrolls that Jews possess today are not letter-perfect, the Torah scrolls are certainly the word-perfect textus receptus that was divinely revealed to Moses. Indeed, the general consensus of Orthodox rabbinic authority posits this belief in the word-perfect nature of the Torah scroll as a defining feature of Orthodox Judaism.[25][26]

Prophecy

[edit]Jews believe that the Almighty Creator at times chooses to prophecy. Many of such occurrences are described in The Nevi'im, the books of the Prophets. However, since the destruction of the first Temple prophecy has ceased. The purpose of prophecy is to reward those who seek God.[27]

Oral Torah

[edit]Orthodox Jews view the Written and Oral Torah as the same as Moses taught, for all practical purposes. Conservative Jews tend to believe that much of the Oral law is divinely inspired, while Reform and Reconstructionist Jews tend to view all of the Oral law as an entirely human creation. Traditionally, the Reform movement held that Jews were obliged to obey the ethical but not the ritual commandments of Scripture, although today many Reform Jews have adopted many traditional ritual practices. Karaite Jews traditionally consider the Written Torah to be authoritative, viewing the Oral Law as only one possible interpretation of the Written Torah. Most Modern Orthodox Jews will agree that, while certain laws within the Oral Law were given to Moses, most of the Talmudic laws were derived organically by the Rabbis of the Mishnaic and Talmudic eras.

People are born with both a tendency to do good and to do evil

[edit]Jewish tradition mostly emphasizes free will, and most Jewish thinkers reject determinism, on the basis that free will and the exercise of free choice have been considered a precondition of moral life.[28] "Moral indeterminacy seems to be assumed both by the Bible, which bids man to choose between good and evil, and by the rabbis, who hold the decision for following the good inclination, rather than the evil, rests with every individual."[28] Maimonides asserted the compatibility of free will with foreknowledge of God.[29][28] Only a handful of Jewish thinkers have expressed deterministic views. This group includes the medieval Jewish philosopher Hasdai Crescas and the 19th-century Hasidic rabbi Mordechai Yosef Leiner of Izbica.[30][31]

All is necessary for God because He is perfect but for mankind all is possible by virtue of choice; the two types of view are true with knowing about the prophet who is in Devekut with God to be wise and to perform miracle for Him.[32]

Judaism affirms that people are born with both a yetzer ha-tov (יצר הטוב), an inclination or impulse to do good, and with a yetzer hara (יצר הרע), an inclination or impulse to do evil. These phrases reflect the concept that "within each person, there are opposing natures continually in conflict" and are referenced many times in the rabbinic tradition.[33] The rabbis even recognize a positive value to the yetzer ha-ra: without the yetzer ha-ra there would be no civilization or other fruits of human labor. Midrash states: "Without the evil inclination, no one would father a child, build a house, or make a career."[34] The implication is that yetzer ha-tov and yetzer ha-ra are best understood not only as moral categories of good and evil, but as the inherent conflict within man between selfless and selfish orientations.

Judaism recognizes two classes of "sin": offenses against other people, and offenses against God. Offenses against God may be understood as violation of a contract (the covenant between God and the Children of Israel). Once a person has sinned, there are various means by which they may obtain atonement (see Atonement in Judaism).

Judaism rejects the belief in "original sin". Both ancient and modern Judaism teaches that every person is responsible for his own actions. The existence of some "innate sinfulness on each human being was discussed" in both biblical (Genesis 8:21, Psalms 51.5) and post-biblical sources;[35] however, in the biblical verses this is brought as an argument for divine mercy, as humans cannot be blamed for the nature they were created with. Some apocrypha and pseudepigraphic sources express pessimism about human nature ("A grain of evil seed was sown in Adam's heart from the beginning"), and the Talmud (b. Avodah Zarah 22b) has an unusual passage which Edward Kessler describes as "the serpent seduced Eve in paradise and impregnated her with spiritual-physical 'dirt' which was inherited through the generations", but the revelation at Sinai and the reception of the Torah cleansed Israel.[35] Kessler states that "although it is clear that belief in some form of original sin did exist in Judaism, it did not become mainstream teaching, nor dogmatically fixed", but remained at the margins of Judaism.[35]

Reward and punishment

[edit]The mainstream Jewish view is that God will reward those who observe His commandments and punish those who intentionally transgress them. Examples of rewards and punishments are described throughout the Bible, and throughout classical rabbinic literature. The common understanding of this principle is accepted by most Orthodox and Conservative and many Reform Jews; it is generally rejected by the Reconstructionists.[36] See also Free will in theology #Judaism

The Bible contains references to Sheol, lit. gloom, as the common destination of the dead, which may be compared with the Hades or underworld of ancient religions. In later tradition, this is interpreted either as Hell or as a literary expression for death or the grave in general.

According to aggadic passages in the Talmud, God judges who has followed His commandments and who does not and to what extent. Those who do not "pass the test" go to a purifying place (sometimes referred to as Gehinnom, i. e., Hell, but more analogous to the Christian Purgatory) to "learn their lesson". There is, however, for the most part, no eternal damnation. The vast majority of souls only go to that reforming place for a limited amount of time (less than one year). Certain categories are spoken of as having "no part in the world to come", but this appears to mean annihilation rather than an eternity of torment.

Philosophical rationalists such as Maimonides believed that God did not actually mete out rewards and punishments as such. In this view, these were beliefs that were necessary for the masses to believe in order to maintain a structured society and to encourage the observance of Judaism. However, once one learned Torah properly, one could then learn the higher truths. In this view, the nature of the reward is that if a person perfected his intellect to the highest degree, then the part of his intellect that connected to God – the active intellect – would be immortalized and enjoy the "Glory of the Presence" for all eternity. The punishment would simply be that this would not happen; no part of one's intellect would be immortalized with God. See Divine Providence in Jewish thought.

The Kabbalah (mystical tradition in Judaism) contains further elaborations, though some Jews do not consider these authoritative. For example, it admits the possibility of reincarnation, which is generally rejected by non-mystical Jewish theologians and philosophers. It also believes in a triple soul, of which the lowest level (nefesh or animal life) dissolves into the elements, the middle layer (ruach or intellect) goes to Gan Eden (Paradise) while the highest level (neshamah or spirit) seeks union with God.

Some Jews consider tikkun olam ('repairing the world') as a fundamental motivating factor in Jewish ethics. Therefore, the concept of "life after death", in the Jewish view, is not encouraged as the motivating factor in performance of Judaism. Indeed, it is held that one can attain closeness to God even in this world through moral and spiritual perfection.

Israel chosen for a purpose

[edit]God chose the Jewish people to be in a unique covenant with God; the description of this covenant is the Torah itself. God further declared in the Torah through prophecy to Moses that his "firstborn" is the Israelites. However, closeness and being chosen does not imply exclusivity as anyone can join and convert. Included in the idea of being chosen is that Jews were chosen for a specific mission, a duty: to be a light unto the nations, and to have a covenant with God as described in the Torah.

Rabbi Lord Immanuel Jakobovits, former Chief Rabbi of the United Synagogue of Great Britain, describes the mainstream Jewish view on this issue: "Yes, I do believe that the chosen people concept as affirmed by Judaism in its holy writ, its prayers, and its millennial tradition. In fact, I believe that every people—and indeed, in a more limited way, every individual—is 'chosen' or destined for some distinct purpose in advancing the designs of Providence. Only, some fulfill their mission and others do not. Maybe the Greeks were chosen for their unique contributions to art and philosophy, the Romans for their pioneering services in law and government, the British for bringing parliamentary rule into the world, and the Americans for piloting democracy in a pluralistic society. The Jews were chosen by God to be 'peculiar unto Me' as the pioneers of religion and morality; that was and is their national purpose."

The messiah

[edit]Judaism acknowledges an afterlife, but does not have a single or systemic way of thinking about the afterlife. Judaism places its overwhelming stress on Olam HaZeh (this world) rather than Olam haba (the World to Come), and "speculations about the World to Come are peripheral to mainstream Judaism".[37] In Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers), it is said that "One hour of penitence and good deeds in this world is better than all the life of the world to come; but one hour of spiritual repose in the world to come is better than all the life of this world", reflecting both a view of the significance of life on Earth and the spiritual repose granted to the righteous in the next world.[37]

Jews reject the idea that Jesus of Nazareth was the messiah and agree that the messiah has not yet come. Throughout Jewish history there have been a number of Jewish Messiah claimants considered false by Jews, including most notably Simon bar Kokhba and Sabbatai Zevi, whose followers were known as Sabbateans.[38]

The twelfth of Maimonides' 13 principles of faith was: "I believe with perfect faith in the coming of the messiah (mashiach), and though he may tarry, still I await him every day." Orthodox Jews believes that a future Jewish messiah (the Mashiach, "anointed one") will be a king who will rule the Jewish people independently and according to Jewish law. In a traditional view, the Messiah was understood to be a human descendant of King David (that is, of the Davidic line).[38]

Liberal, or Reform Judaism does not believe in the arrival of a personal Messiah who will ingather the exiles in the Land of Israel and cause the physical resurrection of the dead. Rather, Reform Jews focus on a future age in which there is a perfected world of justice and mercy.[38]

History and development

[edit]The activities of the various prophets refined, developed and intertwined with the religious beliefs of the early Israelites.[39]

A number of formulations of Jewish beliefs have appeared, and there is some dispute over the number of basic principles. Rabbi Joseph Albo, for instance, in Sefer Ha-Ikkarim (c. 1425 CE) counts three principles of faith, while Maimonides (1138–1204) lists thirteen. While some later rabbis have attempted to reconcile the differences, claiming that Maimonides' principles are covered by Albo's much shorter list, alternative lists provided by other medieval rabbinic authorities seem to indicate some level of tolerance for varying theological perspectives.

No formal text canonized

[edit]Though to a certain extent incorporated in the liturgy and utilized for purposes of instruction, these formulations of the cardinal tenets of Judaism carried no greater weight than that imparted to them by the fame and scholarship of their respective authors. None of them had an authoritative character analogous to that given by Christianity to its three great formulas (the Apostles' Creed, the Nicene or Constantinopolitan, and the Athanasian), or to the Kalimat As-Shahadat of the Muslims. None of the many summaries from the pens of Jewish philosophers and rabbis has been invested with similar importance.[40]

Conversion to Judaism

[edit]Unlike some other religions, Judaism has not made strong attempts to convert non-Jews, although formal conversion to Judaism is permitted. Righteousness, according to Jewish belief, was not restricted to those who accepted the Jewish religion. Maimonides regards the righteous among the nations who carried into practice the seven fundamental laws of the covenant with Noah and his descendants as participants in the felicity of the hereafter.[41] This interpretation of the status of non-Jews made the development of a missionary attitude unnecessary. Moreover, the regulations for the reception of proselytes, as developed in course of time, prove the eminently practical, that is, the non-creedal character of Judaism. Compliance with certain rites – immersion in a mikveh (ritual bath), brit milah (circumcision), and the acceptance of the mitzvot (commandments of the Torah) as binding – is the test of the would-be convert's faith. The convert is instructed in the main points of Jewish law, while the profession of faith demanded is limited to the acknowledgment of the unity of God and the rejection of idolatry. Judah ha-Levi (Kuzari 1:115, c. 1140 CE) states:

- We are not putting on an equality with us a person entering our religion through confession alone. We require deeds, including in that term self-restraint, purity, study of the Law, circumcision, and the performance of other duties demanded by the Torah.

For the preparation of the convert, therefore, no other method of instruction was employed than for the training of one born a Jew. The aim of teaching was to convey a knowledge of halakha (Jewish law), obedience to which manifested the acceptance of the underlying religious principles; namely, the existence of God and the mission of Israel as the people of God's covenant.

Are principles of faith inherent in mitzvot?

[edit]Many scholars have debated whether the practice of mitzvot in Judaism is inherently connected to Judaism's principles of faith. Moses Mendelssohn, in his Jerusalem (1783), defended the non-dogmatic nature of the practice of Judaism. Rather, he asserted, the beliefs of Judaism, although revealed by God in Judaism, consist of universal truths applicable to all mankind. Rabbi Leopold Löw (1811-1875), among others, took the opposite view, and considered that the Mendelssohnian theory had been carried beyond its legitimate bounds. Underlying the practice of the Law was assuredly the recognition of certain fundamental principles, he asserted, culminating in the belief in God and revelation, and likewise in the doctrine of divine justice.

The first to attempt to formulate Jewish principles of faith was Philo of Alexandria in the 1st century CE. He enumerated five articles: God is and rules; God is one; the world was created by God; Creation is one, and God's providence rules Creation.

Belief in the Oral Law

[edit]Many rabbis were drawn into controversies with both Jews and non-Jews, and had to fortify their faith against the attacks of contemporaneous philosophy as well as against rising Christianity. The Mishnah (c. 200 CE) excludes from the world to come the Epicureans and those who deny belief in resurrection or in the divine origin of the Torah.[42] "Rabbi Akiva (died 135 CE) would also regard as heretical the readers of Sefarim Hetsonim[43] – certain extraneous writings that were not canonized – as well such persons that would heal through whispered formulas of magic. Abba Saul designated as under suspicion of infidelity those that pronounce the ineffable name of God."[44] By implication, the contrary doctrine may be regarded as Orthodox. On the other hand, Akiva himself declares that the command to love one's neighbor is the fundamental principle of the Torah; while Ben Asa assigns this distinction to the Biblical verse "This is the book of the generations of man".

The definition of Hillel the Elder (died 10 CE) in his interview with a would-be convert (Talmud, Shabbat 31a) embodies in the golden rule the one fundamental article of faith. Rabbi Simlai (3rd century) traces the development of Jewish religious principles from Moses with his 613 commandments, through David, who, according to this rabbi, enumerates eleven; through Isaiah, with six; Micah, with three; to Habakkuk who simply but impressively sums up all religious faith in the single phrase, "The pious lives in his faith".[45] As Jewish law enjoins that one should prefer death to an act of idolatry, incest, unchastity, or murder, the inference is plain that the corresponding positive principles were held to be fundamental articles of Judaism.

Belief during the medieval era

[edit]Detailed constructions of articles of faith did not find favor in Judaism before the medieval era, when Jews were forced to defend their faith from both Islamic and Christian inquisitions, disputations, and polemics. The necessity of defending their religion against the attacks of other philosophies induced many Jewish leaders to define and formulate their beliefs. Saadia Gaon's Emunot ve-Deot (c. 933 CE) is an exposition of the main tenets of Judaism. Saadia lists these as: The world was created by God; God is one and incorporeal; belief in revelation (including the divine origin of tradition); man is called to righteousness, and endowed with all necessary qualities of mind and soul to avoid sin; belief in reward and punishment; the soul is created pure; after death, it leaves the body; belief in resurrection; Messianic expectation, retribution, and final judgement.

Judah Halevi endeavored, in his Kuzari to determine the fundamentals of Judaism on another basis. He rejects all appeal to speculative reason, repudiating the method of the Islamic Motekallamin. The miracles and traditions are, in their natural character, both the source and the evidence of the true faith. In this view, speculative reason is considered fallible due to the inherent impossibility of objectivity in investigations with moral implications.

Maimonides' 13 principles of faith

[edit]13 Principles of Faith, summarized:

- I believe with perfect faith that the Creator, Blessed be His Name, is the Creator and Guide of everything that has been created; He alone has made, does make, and will make all things.

- I believe with perfect faith that the Creator, Blessed be His Name, is One, and that there is no unity in any manner like His, and that He alone is our God, who was, and is, and will be.

- I believe with perfect faith that the Creator, Blessed be His Name, has no body, and that He is free from all the properties of matter, and that there can be no (physical) comparison to Him whatsoever.

- I believe with perfect faith that the Creator, Blessed be His Name, is the first and the last.

- I believe with perfect faith that to the Creator, Blessed be His Name, and to Him alone, it is right to pray, and that it is not right to pray to any being besides Him.

- I believe with perfect faith that all the words of the prophets are true.

- I believe with perfect faith that the prophecy of Moses our teacher, peace be upon him, was true, and that he was the chief of the prophets, both those who preceded him and those who followed him.

- I believe with perfect faith that the entire Torah that is now in our possession is the same that was given to Moses our teacher, peace be upon him.

- I believe with perfect faith that this Torah will not be exchanged, and that there will never be any other Torah from the Creator, Blessed be His Name.

- I believe with perfect faith that the Creator, Blessed be His Name, knows all the deeds of human beings and all their thoughts, as it is written, "Who fashioned the hearts of them all, Who comprehends all their actions" (Psalm 33:15).

- I believe with perfect faith that the Creator, Blessed be His Name, rewards those who keep His commandments and punishes those that transgress them.

- I believe with perfect faith in the coming of the Messiah; and even though he may tarry, nonetheless, I wait every day for his coming.

- I believe with perfect faith that there will be a revival of the dead at the time when it shall please the Creator, Blessed be His name, and His mention shall be exalted for ever and ever.

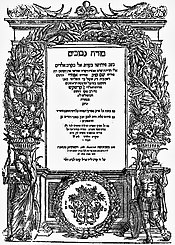

Rabbi Moses ben Maimon, better known as Maimonides or "The Rambam" (1135–1204 CE), lived at a time when both Christianity and Islam were developing active theologies. Jewish scholars were often asked to attest to their faith by their counterparts in other religions. The Rambam's 13 principles of faith were formulated in his commentary on the Mishnah (tractate Sanhedrin, chapter 10). They were one of several efforts by Jewish theologians in the Middle Ages to compile such a list. By the time of Maimonides, centers of Jewish learning and law were dispersed geographically. Judaism no longer had a central authority that might bestow official approval on any list of principles of faith.

Maimonides' 13 principles evoked criticism from Crescas (c. 1340 – 1410/11) and from Joseph Albo (c. 1380 – 1444). They evoked criticism as minimizing acceptance of the entire Torah (Rabbi S. of Montpelier, Yad Rama, Y. Alfacher, Rosh Amanah). The 13 principles are simultaneously understood as rooted in legitimate Talmudic scholarship and Jewish tradition, and also remain somewhat controversial as scholars who both preceded and succeeded Maimonides (and Maimonides himself, in one case[47]) offered different views.[47][48] Over time two poetic restatements of these principles (Ani Ma'amin and Yigdal) became canonized in the Jewish prayerbook. Eventually, Maimonides' 13 principles of faith became the most widely accepted statement of belief.

Importantly, Maimonides, while enumerating the above, added the following caveat:

"There is no difference between [the Biblical statement] 'his wife was Mehithabel' [Genesis 10,6] on the one hand [i. e., an "unimportant" verse], and 'Hear, O Israel' on the other [i. e., an "important" verse]... anyone who denies even such verses thereby denies God and shows contempt for his teachings more than any other skeptic, because he holds that the Torah can be divided into essential and non-essential parts..."

The uniqueness of the 13 fundamental beliefs was that even a rejection out of ignorance placed one outside Judaism, whereas the rejection of the rest of Torah must be a conscious act to stamp one as an unbeliever. Others, such as Rabbi Joseph Albo and the Raavad, criticized Maimonides' list as containing items that, while true, in their opinion did not place those who rejected them out of ignorance in the category of heretics. Many others criticized any such formulation as minimizing acceptance of the entire Torah. As noted, however, neither Maimonides nor his contemporaries viewed these principles as encompassing all of Jewish belief, but rather as the core theological underpinnings of the acceptance of Judaism.

Some modern Orthodox scholars have pointed out apparent inconsistencies in Maimonides's writings with respect to the 13 principles of faith.[49][50]

Karaite articles

[edit]A contemporary of Maimonides, the 12th-century Karaite scholar and liturgist Judah ben Elijah Hadassi in his Eshkol ha-Kofer formulated non-Rabbinic articles of faith:

(1) God is the Creator of all created beings; (2) He is premundane and has no peer or associate; (3) the whole universe is created; (4) God called Moses and the other Prophets of the Biblical canon; (5) the Law of Moses alone is true; (6) to know the language of the Bible is a religious duty; (7) the Temple at Jerusalem is the palace of the world's Ruler; (8) belief in Resurrection contemporaneous with the advent of the Messiah; (9) final judgment; (10) retribution.

— Judah ben Elijah Hadassi, Eshkol ha-Kofer[40]

After Maimonides

[edit]Some successors of Maimonides, from the 13th to the 15th centuries — Nahmanides, Abba Mari ben Moses, Simon ben Zemah Duran, Joseph Albo, Isaac Arama, and Joseph Jaabez — narrowed his 13 articles to three core beliefs: belief in God; in creation (or revelation); and in providence (or retribution).

Others, like Crescas and David ben Samuel Estella, spoke of seven fundamental articles, laying stress on free-will. On the other hand, David ben Yom-Tob ibn Bilia, in his Yesodot ha- Maskil (Fundamentals of the Thinking Man), adds to the 13 of Maimonides 13 of his own — a number which a contemporary of Albo also chose for his fundamentals; while Jedaiah Penini (c. 1270 – c. 1340) , in the last chapter of his "Behinat ha-Dat", enumerated no fewer than 35 cardinal principles.

Isaac Abarbanel, in his Rosh Amanah (The Pinnacle of Faith, 1505), took the same attitude towards Maimonides' creed. While defending Maimonides against Hasdai and Albo, he refused to accept dogmatic articles for Judaism, criticizing any formulation as minimizing acceptance of all 613 mitzvot.

The Enlightenment

[edit]In the late-18th century Europe was swept by a group of intellectual, social and political movements, together known as the Enlightenment. These movements promoted scientific thinking and free thought; they allowed people to question previously unshaken religious dogmas. Like Christianity, Judaism developed several responses to this unprecedented phenomenon. One response saw the Enlightenment as positive, while another saw it as negative. The Enlightenment meant equality and freedom for many Jews in many countries, so some felt that it should be warmly welcomed. Scientific study of religious texts would allow people to study the history of Judaism. Some Jews felt that Judaism should accept modern secular thought and change in response to these ideas. Others, however, believed that the divine nature of Judaism precluded changing any fundamental beliefs.

While the modernist wing of Orthodox Judaism, led by such rabbis as Samson Raphael Hirsch (1808-1888), was open to the changing times, it rejected any doubt in the traditional theological foundation of Judaism. Historical-critical methods of research and new philosophy led to the formation of various non-Orthodox denominations, as well as of Jewish secular movements.

Principles of faith in Modern Judaism

[edit]Orthodox Judaism

[edit]Orthodox Judaism continuously maintained the historical rabbinic Judaism. Therefore, as above, it accepts philosophic speculation and statements of dogma only to the extent that they exist within, and are compatible with, the system of written and oral Torah. As a matter of practice, Orthodox Judaism lays stress on the performance of the actual commandments. Dogma is considered to be the self-understood underpinning of the practice of the Mitzvot.[51]

Owing to this, there is no one official statement of principles. Rather, all formulations by accepted early Torah leaders are considered to have possible validity. The 13 principles of Maimonides have been cited by adherents as the most influential: They are often printed in prayer books, and in some congregations, a hymn (Yigdal) incorporating them is sung on Friday nights or even every morning in some communities.

Conservative Judaism

[edit]Conservative Judaism developed in Europe and the United States in the late 1800s, as Jews reacted to the changes brought about by the Jewish Enlightenment and Jewish emancipation. In many ways, it was a reaction to what were seen as the excesses of the Reform movement. For much of the movement's history, Conservative Judaism deliberately avoided publishing systematic explications of theology and belief; this was a conscious attempt to hold together a wide coalition. This concern became a non-issue after the left-wing of the movement seceded in 1968 to form the Reconstructionist movement, and after the right-wing seceded in 1985 to form the Union for Traditional Judaism.

In 1988, the Leadership Council of Conservative Judaism finally issued an official statement of belief, "Emet Ve-Emunah: Statement of Principles of Conservative Judaism". It noted that a Jew must hold certain beliefs. However, the Conservative rabbinate also notes that the Jewish community never developed any one binding catechism. Thus, Emet Ve-Emunah affirms belief in God and in God's revelation of Torah to the Jews. However, it also affirms the legitimacy of multiple interpretations of these issues. Atheism, Trinitarian views of God, and polytheism are all ruled out. All forms of relativism, and also of literalism and fundamentalism, are also rejected. It teaches that Jewish law is both still valid and indispensable, but also holds to a more open and flexible view of how law has, and should, develop than the Orthodox view.

Reform Judaism

[edit]Reform Judaism has had a number of official platforms, especially in the United States. The first platform was the 1885 Declaration of Principles ("The Pittsburgh Platform")[52] – the adopted statement of a meeting of reform rabbis from across the United States November 16 – 19, 1885.

The next platform – The Guiding Principles of Reform Judaism ("The Columbus Platform")[53] – was published by the Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR) in 1937.

The CCAR rewrote its principles in 1976 with its Reform Judaism: A Centenary Perspective[54] and rewrote them again in 1999's A Statement of Principles for Reform Judaism.[55] While original drafts of the 1999 statement called for Reform Jews to consider re-adopting some traditional practices on a voluntary basis, later drafts removed most of these suggestions. The final version is thus similar to the 1976 statement.

According to the CCAR, personal autonomy still has precedence over these platforms; lay people need not accept all, or even any, of the beliefs stated in these platforms. Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR) President Rabbi Simeon J. Maslin wrote a pamphlet about Reform Judaism, entitled "What We Believe... What We Do...". It states that, "If anyone were to attempt to answer these two questions authoritatively for all Reform Jews, that person's answers would have to be false. Why? Because one of the guiding principles of Reform Judaism is the autonomy of the individual. A Reform Jew has the right to decide whether to subscribe to this particular belief or to that particular practice." Reform Judaism affirms "the fundamental principle of Liberalism: that the individual will approach this body of mitzvot and minhagim in the spirit of freedom and choice. Traditionally, Israel started with harut, the commandment engraved upon the Tablets, which then became freedom. The Reform Jew starts with herut, the freedom to decide what will be harut - engraved upon the personal Tablets of his life." [Bernard Martin, Ed., Contemporary Reform Jewish Thought, Quadrangle Books 1968.] In addition to those, there were the 42 Affirmations of Liberal Judaism in Britain from 1992, and the older Richtlinien zu einem Programm für das liberale Judentum (1912) in Germany, as well as others, all stressing personal autonomy and ongoing revelation.

Reconstructionist Judaism

[edit]Reconstructionist Judaism is an American denomination that has a naturalist theology as developed by Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan.[56] This theology is a variant of the naturalism of John Dewey, which combined atheistic beliefs with religious terminology in order to construct a religiously satisfying philosophy for those who had lost faith in traditional religion. [See id. at 385; but see Caplan at p. 23, fn.62 ("The majority of Kaplan's views ... were formulated before he read Dewey or [William] James."[57])] Reconstructionism posits that God is neither personal nor supernatural. Rather, God is said to be the sum of all natural processes that allow man to become self-fulfilled. Rabbi Kaplan wrote that "to believe in God means to take for granted that it is man's destiny to rise above the brute and to eliminate all forms of violence and exploitation from human society".

Many Reconstructionist Jews reject theism, and instead define themselves as religious naturalists. These views have been criticized on the grounds that they are actually atheists, which has only been made palatable to Jews by rewriting the dictionary. A significant minority of Reconstructionists have refused to accept Kaplan's theology, and instead affirm a theistic view of God.

As in Reform Judaism, Reconstructionist Judaism holds that personal autonomy has precedence over Jewish law and theology. It does not ask that its adherents hold to any particular beliefs, nor does it ask that halakha be accepted as normative. In 1986, the Reconstructionist Rabbinical Association (RRA) and the Federation of Reconstructionist Congregations (FRC) passed the official "Platform on Reconstructionism" (2 pages). It is not a mandatory statement of principles, but rather a consensus of current beliefs. [FRC Newsletter, Sept. 1986, pages D, E.] Major points of the platform state that:

- Judaism is the result of natural human development. There is no such thing as divine intervention.

- Judaism is an evolving religious civilization.

- Zionism and aliyah (immigration to Israel) are encouraged.

- The laity can make decisions, not just rabbis.

- The Torah was not inspired by God; it only comes from the social and historical development of Jewish people.

- All classical views of God are rejected. God is redefined as the sum of natural powers or processes that allows mankind to gain self-fulfillment and moral improvement.

- The idea that God chose the Jewish people for any purpose, in any way, is "morally untenable", because anyone who has such beliefs "implies the superiority of the elect community and the rejection of others".

This platform puts Reconstructionist Jews at odds with all other Jews, as it seems to accuse all other Jews of being racist. Jews outside of the Reconstructionist movement strenuously reject this charge.

Although Reconstructionist Judaism does not require its membership to subscribe to any particular dogma, the Reconstructionist movement actively rejects or marginalizes certain beliefs held by other branches of Judaism, including many (if not all) of the 13 Principles. For example, Rabbi Kaplan "rejected traditional Jewish understandings of messianism. His God did not have the ability to suspend the natural order, and could thus not send a divine agent from the house of David who would bring about a miraculous redemption."[57] Rather, in keeping with Reconstructionist naturalist principles, "Kaplan believed strongly that ultimately, the world will be perfected, but only as a result of the combined efforts of humanity over generations." (Id. at 57) Similarly, Reconstructionism rejects the 13th principle of resurrection of the dead, which Kaplan believed "belonged to a supernatural worldview rejected by moderns". (Id. at 58.) Thus, the Reconstructionist Sabbath Prayer Book erases all references to a messianic figure, and the daily 'Amidah replaces the traditional blessing of reviving the dead with one that blesses God "who in love remembers Thy creatures unto life". (Id. at 57-59.)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Louis Jacobs, "Chapter 2: The Unity of God" in A Jewish Theology (1973). Behrman House.

- ^ Deut 6:4–9

- ^ Aryeh Kaplan, The Handbook of Jewish Thought (1979). e Maznaim: p. 9.

- ^ Jewish Theology and Process Thought (eds. Sandra B. Lubarsky & David Ray Griffin). SUNY Press, 1996.

- ^ How Old is the Universe? How Old is the Universe?, NASA; Phil Plait, The Universe Is 13.82 Billion Years Old (March 21, 2013), Slate

- ^ Norbert Max Samuelson, Revelation and the God of Israel (2002). Cambridge University Press: p. 126.

- ^ Maimonides, The Guide of the Perplexed, translated by Chaim Menachem Rabin (Hackett, 1995).

- ^ Guide for the Perplexed 2:13

- ^ Dan Cohn-Sherbok, Judaism: History, Belief, and Practice (2003). Psychology Press: p. 359.

- ^ Louis Jacobs, "Chapter 6: Eternity" in A Jewish Theology (1973). Behrman House: p. 81-93.

- ^ a b Louis Jacobs, "Chapter 5: Omnipotence and Omniscience" in A Jewish Theology (1973). Behrman House: p. 76-77.

- ^ a b Clark M. Williamson, A Guest in the House of Israel: Post-Holocaust Church Theology (1993). Westminster John Knox Press: pp. 210-215.

- ^ a b Samuel S. Cohon. What We Jews Believe (1931). Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

- ^ a b c d e Edward Kessler, What Do Jews Believe?: The Customs and Culture of Modern Judaism (2007). Bloomsbury Publishing: pp. 42-44.

- ^ Morris N. Kertzer, What Is a Jew (1996). Simon and Schuster: pp. 15-16.

- ^ Joseph Telushkin, Jewish Literacy: The Most Important Things to Know About the Jewish Religion, Its People, and Its History (Revised Edition) (2008). HarperCollins: p. 472.

- ^ http://www.pewforum.org/files/2013/05/report-religious-landscape-study-full.pdf Archived 2017-04-17 at the Wayback Machine, p. 164

- ^ "Mishnah Sanhedrin 10:1".

- ^ a b Peter A. Pettit, "Hebrew Bible" in A Dictionary of Jewish-Christian Relations (2005). Eds. Edward Kessler and Neil Wenborn. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Christopher Hugh Partridge, Introduction to World Religions (2005). Fortress Press: pp 283-286.

- ^ a b Jacob Neusner, The Talmud: What It Is and What It Says (2006). Rowman & Littlefield.

- ^ a b Adin Steinsaltz, "Chapter 1: What is the Talmud?" in The Essential Talmud (2006). Basic Books: pp. 3-9.

- ^ Commentary to the Mishna, preface to chapter "Chelek", Tractate Sanhedrin; Mishneh Torah, Laws of the foundations of the Torah, ch. 7

- ^ Sarna, Johnathan D. (2004). American Judaism: A History. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. pp. 246.

- ^ Fishman, Sylvia Barack. "CHANGING MINDS: Feminism in Contemporary Orthodox Jewish Life" (PDF). p. 9 (19). Retrieved January 29, 2024.

Second, Orthodox Jews are presumed to feel allegiance to some interpretation of the traditional concept of divine revelation of Jewish law, torah mi sinai, a belief that the complex, prescriptive codes of rabbinic law derive from God's articulated instructions to the Jewish people. A very broad interpretive gamut is reflected as Orthodox Jews of various shades and stripes formulate what torah mi sinai means to them. However, no matter how liberal an individual Orthodox person's interpretation of divine revelation, daily life is influenced by a group of observances that are precisely dictated by written texts.

- ^ "Denominational Differences On Conversion". My Jewish Learning. Retrieved 2024-01-29.

- ^ https://www.sefaria.org/Mishnah_Sanhedrin.10.1?lang=bi&p2=Rambam_on_Mishnah_Sanhedrin.10.1.21&lang2=bi

- ^ a b c Determinism, in The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion (ed. Adele Berlin, Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 210.

- ^ Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Teshuvah 5

- ^ Louis Jacobs, A Jewish Theology (Behrman House, 1973), p. 79.

- ^ Alan Brill, Thinking God: The Mysticism of Rabbi Zadok of Lublin (KTAV Publishing, 2002), p. 134.

- ^ ”Or Adonai” by Hasdai Crescas

- ^ Ronald L. Eisenberg, What the Rabbis Said: 250 Topics from the Talmud (2010). ABC-CLIO: pp. 311-313.

- ^ Bereshit Rabbah 9:7

- ^ a b c Edward Kessler, "Original Sin" in A Dictionary of Jewish-Christian Relations (eds. Edward Kessler & Neil Wenborn, Cambridge University Press, 2005) pp. 323-324.

- ^ Rebecca Alpert (2011). "Judaism, Reconstructionist". The Cambridge Dictionary of Judaism and Jewish Culture. Cambridge University Press. p. 346.

- ^ a b Marc Angel, "Afterlife" in A Dictionary of the Jewish-Christian Dialogue (1995). Eds. Leon Klenicki and Geoffrey Wigoder. Paulist Press: pp. 3-5.

- ^ a b c Eugene B. Borowitz, Naomi Patz, "Chapter 19: Our Hope for a Messianic Age" in Explaining Reform Judaism (1985). Behrman House.

- ^

Lods, Adolphe (1955) [1935]. The Prophets and the Rise of Judaism. Translated by Hooke, Samuel Henry. K. Paul, Trench, Trubner. p. 110, 151. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

Isaiah sometimes defines the normal attitude which Jahweh is entitled to expect from the nation by a word which Christianity was to make extremely popular, namely, faith. [...] into the very centre of the spiritual religion which the prophets had hoped to build up, a wedge of popular belief was driven: the belief in the Temple of Jerusalem and its ritual.

- ^ a b

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Kohler, Kaufmann; Hirsch, Emil G. (1901–1906). "Articles of Faith". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Kohler, Kaufmann; Hirsch, Emil G. (1901–1906). "Articles of Faith". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Schwarzschild, Steven S. "Noachide Laws". Encyclopaedia Judaica. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

Maimonides equates the 'righteous man (ḥasid) of the [gentile] nations' who has a share in the world to come even without becoming a Jew with the gentile who keeps [the Noachide] laws.

- ^ Mishnah, Sanhedrin 11:1

- ^ Sefarim Chitsonim

- ^ "Articles of Faith". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2024-01-29.

- ^ Talmud, Makkot, toward end

- ^ David Birnbaum, Jews, Church & Civilization, Volume III (Millennium Education Foundation 2005)

- ^ a b "The Thirteen Principles of Faith". My Jewish Learning. Retrieved 2024-01-30.

- ^ Shapiro, Marc B. (1993). "Maimonides' Thirteen Principles: The Last Word in Jewish Theology?". The Torah U-Madda Journal. 4: 187–242. ISSN 1050-4745. JSTOR 40914883.

- ^ Kellner, Menachem Marc (2006-01-01). Must a Jew Believe Anything?. Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. ISBN 9781904113386.

- ^ Shapiro, Marc B. (2004-01-01). The limits of Orthodox theology: Maimonides' Thirteen principles reappraised. Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. ISBN 9781874774907.

- ^ Hammer, Reuven (2010). "Judaism as a System of Mitzvot". Conservative Judaism. 61 (3): 12–25. doi:10.1353/coj.2010.0022. ISSN 1947-4717. S2CID 161398603.

- ^ "Declaration of Principles – "The Pittsburgh Platform"". The Central Conference of American Rabbis. 1885. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- ^ "The Guiding Principles of Reform Judaism – "The Columbus Platform"". The Central Conference of American Rabbis. 1937. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- ^ "Reform Judaism: A Centenary Perspective". The Central Conference of American Rabbis. 1976. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- ^ "A Statement of Principles for Reform Judaism". The Central Conference of American Rabbis. 1999. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- ^ Mordecai M. Kaplan, Judaism as a Civilization: Toward a Reconstruction of American-Jewish Life (MacMillan Company 1934), reprinted by Jewish Publication Society 2010.

- ^ a b Eric Caplan, From Ideology to Liturgy: Reconstructionist Worship and American Liberal Judaism (Hebrew Union College Press 2002)

Further reading

[edit]- Blech, Benjamin Understanding Judaism: The Basics of Deed and Creed Jason Aronson; 1992, ISBN 0-87668-291-3.

- Bleich, J. David (ed.), With Perfect Faith: The Foundations of Jewish Belief, Ktav Publishing House, Inc.; 1983. ISBN 0-87068-452-3

- Boteach, Shmuel, Wisdom, Understanding, and Knowledge: Basic Concepts of Hasidic Thought Jason Aronson; 1995. Paperback. ISBN 0-87668-557-2

- Dorff, Elliot N. and Louis E. Newman (eds.) Contemporary Jewish Theology: A Reader, Oxford University Press; 1998. ISBN 0-19-511467-1.

- Dorff, Elliot N. Conservative Judaism: Our Ancestors to Our Descendants (Revised edition) United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, 1996

- Platform on Reconstructionism, FRC Newsletter, Sept. 1986

- Fox, Marvin Interpreting Maimonides, Univ. of Chicago Press. 1990

- Robert Gordis (Ed.) Emet Ve-Emunah: Statement of Principles of Conservative Judaism JTS, Rabbinical Assembly, and the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, 1988

- Julius Guttmann, Philosophies of Judaism, Translated by David Silverman, JPS, 1964

- Jacobs, Louis, Principles of the Jewish Faith: An Analytical Study, 1964.

- Maimonides' Principles: The Fundamentals of Jewish Faith, in "The Aryeh Kaplan Anthology, Volume I", Mesorah Publications 1994

- Kaplan, Mordecai M., Judaism as a Civilization, Reconstructionist Press, New York. 1935. Jewish Publication Society; 1994

- Kellner, Menachem, Dogma in Medieval Jewish Thought, Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Maslin, Simeon J., Melvin Merians and Alexander M. Schindler, What We Believe...What We Do...: A Pocket Guide for Reform Jews, UAHC Press, 1998

- Shapiro, Marc B., "Maimonides Thirteen Principles: The Last Word in Jewish Theology?" in The Torah U-Maddah Journal, Vol. 4, 1993, Yeshiva University.

- Shapiro, Marc B., The Limits of Orthodox Theology: Maimonides' Thirteen Principles Reappraised, The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization; 2004, ISBN 1-874774-90-0.