Meteor

A meteor, known colloquially as a shooting star, is a glowing streak of a small body (usually meteoroid) going through Earth's atmosphere, after being heated to incandescence by collisions with air molecules in the upper atmosphere,[2][3][4] creating a streak of light via its rapid motion and sometimes also by shedding glowing material in its wake. Although a meteor may seem to be a few thousand feet from the Earth,[5] meteors typically occur in the mesosphere at altitudes from 76 to 100 km (250,000 to 330,000 ft).[6][7] The root word meteor comes from the Greek meteōros, meaning "high in the air".[3]

Millions of meteors occur in Earth's atmosphere daily. Most meteoroids that cause meteors are about the size of a grain of sand, i.e. they are usually millimeter-sized or smaller. Meteoroid sizes can be calculated from their mass and density which, in turn, can be estimated from the observed meteor trajectory in the upper atmosphere. [8] Meteors may occur in showers, which arise when Earth passes through a stream of debris left by a comet, or as "random" or "sporadic" meteors, not associated with a specific stream of space debris. A number of specific meteors have been observed, largely by members of the public and largely by accident, but with enough detail that orbits of the meteoroids producing the meteors have been calculated. The atmospheric velocities of meteors result from the movement of Earth around the Sun at about 30 km/s (67,000 mph),[9] the orbital speeds of meteoroids, and the gravity well of Earth.

Meteors become visible between about 75 to 120 km (47 to 75 mi) above Earth. They usually disintegrate at altitudes of 50 to 95 kilometres (31 to 59 mi).[10] Meteors have roughly a fifty percent chance of a daylight (or near daylight) collision with Earth. Most meteors are, however, observed at night, when darkness allows fainter objects to be recognized. For bodies with a size scale larger than 10 cm (3.9 in) to several meters meteor visibility is due to the atmospheric ram pressure (not friction) that heats the meteoroid so that it glows and creates a shining trail of gases and melted meteoroid particles. The gases include vaporised meteoroid material and atmospheric gases that heat up when the meteoroid passes through the atmosphere. Most meteors glow for about a second.

History

[edit]Meteors were not known to be an astronomical phenomenon until early in the nineteenth century. Before that, they were seen in the West as an atmospheric phenomenon, like lightning, and were not connected with strange stories of rocks falling from the sky. In 1807, Yale University chemistry professor Benjamin Silliman investigated a meteorite that fell in Weston, Connecticut.[11] Silliman believed the meteor had a cosmic origin, but meteors did not attract much attention from astronomers until the spectacular meteor storm of November 1833.[12] People all across the eastern United States saw thousands of meteors, radiating from a single point in the sky. Careful observers noticed that the radiant, as the point is called, moved with the stars, staying in the constellation Leo.[13]

The astronomer Denison Olmsted extensively studied this storm, concluding that it had a cosmic origin. After reviewing historical records, Heinrich Wilhelm Matthias Olbers predicted the storm's return in 1867, drawing other astronomers' attention to the phenomenon. Hubert A. Newton's more thorough historical work led to a refined prediction of 1866, which proved correct.[12] With Giovanni Schiaparelli's success in connecting the Leonids (as they are called) with comet Tempel-Tuttle, the cosmic origin of meteors was firmly established. Still, they remain an atmospheric phenomenon and retain their name "meteor" from the Greek word for "atmospheric".[14]

Fireball

[edit]A fireball is a brighter-than-usual meteor which can be also seen during daylight. The International Astronomical Union (IAU) defines a fireball as "a meteor brighter than any of the planets" (apparent magnitude −4 or greater).[15] The International Meteor Organization (an amateur organization that studies meteors) has a more rigid definition. It defines a fireball as a meteor that would have at least magnitude of −3 if seen at zenith. This definition corrects for the greater distance between an observer and a meteor near the horizon. For example, a meteor of magnitude −1 at 5 degrees above the horizon would be classified as a fireball because, if the observer had been directly below the meteor, it would have appeared as magnitude −6.[16]

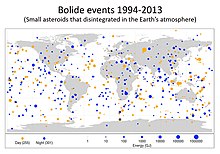

Fireballs reaching apparent magnitude −14 or brighter are called bolides.[17] The IAU has no official definition of "bolide", and generally considers the term synonymous with "fireball". Astronomers often use "bolide" to identify an exceptionally bright fireball, particularly one that explodes in a meteor air burst.[18] They are sometimes called detonating fireballs. It may also be used to mean a fireball which creates audible sounds. In the late twentieth century, bolide has also come to mean any object that hits Earth and explodes, with no regard to its composition (asteroid or comet).[19] The word bolide comes from the Greek βολίς (bolis) [20] which can mean a missile or to flash. If the magnitude of a bolide reaches −17 or brighter it is known as a superbolide.[17][21] A relatively small percentage of fireballs hit Earth's atmosphere and then pass out again: these are termed Earth-grazing fireballs. Such an event happened in broad daylight over North America in 1972. Another rare phenomenon is a meteor procession, where the meteor breaks up into several fireballs traveling nearly parallel to the surface of Earth.

A steadily growing number of fireballs are recorded at the American Meteor Society every year.[22] There are probably more than 500,000 fireballs a year,[23] but most go unnoticed because most occur over the ocean and half occur during daytime. A European Fireball Network and a NASA All-sky Fireball Network detect and track many fireballs.[24]

| Year | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 734 | 676 | 953 | 1,660 | 2,183 | 3,599 | 3,789 | 4,250 | 5,391 | 5,510 | 5,993 | 6,978 | 8,259 | 9,629 |

Effect on atmosphere

[edit]

The entry of meteoroids into Earth's atmosphere produces three main effects: ionization of atmospheric molecules, dust that the meteoroid sheds, and the sound of passage. During the entry of a meteoroid or asteroid into the upper atmosphere, an ionization trail is created, where the air molecules are ionized by the passage of the meteor. Such ionization trails can last up to 45 minutes at a time.

Small, sand-grain sized meteoroids are entering the atmosphere constantly, essentially every few seconds in any given region of the atmosphere, and thus ionization trails can be found in the upper atmosphere more or less continuously. When radio waves are bounced off these trails, it is called meteor burst communications. Meteor radars can measure atmospheric density and winds by measuring the decay rate and Doppler shift of a meteor trail. Most meteoroids burn up when they enter the atmosphere. The left-over debris is called meteoric dust or just meteor dust. Meteor dust particles can persist in the atmosphere for up to several months. These particles might affect climate, both by scattering electromagnetic radiation and by catalyzing chemical reactions in the upper atmosphere.[25] Meteoroids or their fragments achieve dark flight after deceleration to terminal velocity.[26] Dark flight starts when they decelerate to about 2–4 km/s (4,500–8,900 mph). [27] Larger fragments fall further down the strewn field.

Colours

[edit]

The visible light produced by a meteor may take on various hues, depending on the chemical composition of the meteoroid, and the speed of its movement through the atmosphere. As layers of the meteoroid abrade and ionize, the colour of the light emitted may change according to the layering of minerals. Colours of meteors depend on the relative influence of the metallic content of the meteoroid versus the superheated air plasma, which its passage engenders:[28]

- Orange-yellow (sodium)

- Yellow (iron)

- Blue-green (magnesium)

- Violet (calcium)

- Red (atmospheric nitrogen and oxygen)

Acoustic manifestations

[edit]The sound generated by a meteor in the upper atmosphere, such as a sonic boom, typically arrives many seconds after the visual light from a meteor disappears. Occasionally, as with the Leonid meteor shower of 2001, "crackling", "swishing", or "hissing" sounds have been reported,[29] occurring at the same instant as a meteor flare. These are sometimes called electrophonic sounds.[30] Similar sounds have also been reported during intense displays of Earth's auroras.[31][32][33][34]

Theories on the generation of these sounds may partially explain them. For example, scientists at NASA suggested that the turbulent ionized wake of a meteor interacts with Earth's magnetic field, generating pulses of radio waves. As the trail dissipates, megawatts of electromagnetic power could be released, with a peak in the power spectrum at audio frequencies. Physical vibrations induced by the electromagnetic impulses would then be heard if they are powerful enough to make grasses, plants, eyeglass frames, the hearer's own body (see microwave auditory effect), and other conductive materials vibrate.[35][36][37][38] This proposed mechanism, although proven plausible by laboratory work, remains unsupported by corresponding measurements in the field. Sound recordings made under controlled conditions in Mongolia in 1998 support the contention that the sounds are real.[39] (Also see Bolide.)

Meteor shower

[edit]

A meteor shower is the result of an interaction between a planet, such as Earth, and streams of debris from a comet or other source. The passage of Earth through cosmic debris from comets and other sources is a recurring event in many cases. Comets can produce debris by water vapor drag, as demonstrated by Fred Whipple in 1951,[40] and by breakup. Each time a comet swings by the Sun in its orbit, some of its ice vaporizes and a certain amount of meteoroids are shed. The meteoroids spread out along the entire orbit of the comet to form a meteoroid stream, also known as a "dust trail" (as opposed to a comet's "dust tail" caused by the very small particles that are quickly blown away by solar radiation pressure).

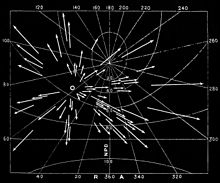

The frequency of fireball sightings increases by about 10–30% during the weeks of vernal equinox.[41] Even meteorite falls are more common during the northern hemisphere's spring season. Although this phenomenon has been known for quite some time, the reason behind the anomaly is not fully understood by scientists. Some researchers attribute this to an intrinsic variation in the meteoroid population along Earth's orbit, with a peak in big fireball-producing debris around spring and early summer. Others have pointed out that during this period the ecliptic is (in the northern hemisphere) high in the sky in the late afternoon and early evening. This means that fireball radiants with an asteroidal source are high in the sky (facilitating relatively high rates) at the moment the meteoroids "catch up" with Earth, coming from behind going in the same direction as Earth. This causes relatively low relative speeds and from this low entry speeds, which facilitates survival of meteorites.[42] It also generates high fireball rates in the early evening, increasing chances of eyewitness reports. This explains a part, but perhaps not all of the seasonal variation. Research is in progress for mapping the orbits of the meteors to gain a better understanding of the phenomenon.[43]

Notable meteors

[edit]

- 1992 – Peekskill, New York

- The Peekskill Meteorite was recorded on October 9, 1992 by at least 16 independent videographers.[44] Eyewitness accounts indicate the fireball entry of the Peekskill meteorite started over West Virginia at 23:48 UT (±1 min). The fireball, which traveled in a northeasterly direction, had a pronounced greenish colour, and attained an estimated peak visual magnitude of −13. During a luminous flight time that exceeded 40 seconds the fireball covered a ground path of some 430 to 500 mi (700 to 800 km).[45] One meteorite recovered at Peekskill, New York, for which the event and object gained their name, had a mass of 27 lb (12.4 kg) and was subsequently identified as an H6 monomict breccia meteorite.[46] The video record suggests that the Peekskill meteorite had several companions over a wide area. The companions are unlikely to be recovered in the hilly, wooded terrain in the vicinity of Peekskill.

- 2009 – Bone, Indonesia

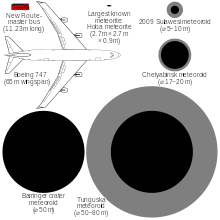

- A large fireball was observed in the skies near Bone, Sulawesi, Indonesia on October 8, 2009. This was thought to be caused by an asteroid approximately 10 m (33 ft) in diameter. The fireball contained an estimated energy of 50 kilotons of TNT, or about twice the Nagasaki atomic bomb. No injuries were reported.[47]

- 2009 – Southwestern US

- A large bolide was reported on 18 November 2009 over southeastern California, northern Arizona, Utah, Wyoming, Idaho and Colorado. At 00:07 local time a security camera at the high altitude W. L. Eccles Observatory (9,610 ft (2,930 m) above sea level) recorded a movie of the passage of the object to the north.[48][49] It had a spherical "ghost" image slightly trailing the main object (likely a lens reflection of the intense fireball), and a bright fireball explosion associated with the breakup of a substantial fraction of the object. An object trail continued northward after the fireball. The shock from the final breakup triggered seven seismological stations in northern Utah. The seismic data yielded a terminal location of the object at 40.286 N, −113.191 W, altitude 90,000 ft (27 km).[citation needed] This is above the Dugway Proving Grounds, a closed Army testing base.

- 2013 – Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia

- The Chelyabinsk meteor was an extremely bright, exploding fireball, or superbolide, measuring about 17 to 20 m (56 to 66 ft) across, with an estimated mass of 11,000 tonnes as the relatively small asteroid entered Earth's atmosphere.[50][51] It was the largest natural object known to have entered Earth's atmosphere since the Tunguska event in 1908. Over 1,500 people were injured, mostly by glass from shattered windows caused by the air burst approximately 25 to 30 km (80,000 to 100,000 ft) above the environs of Chelyabinsk, Russia on 15 February 2013. An increasingly bright streak was observed during morning daylight with a large contrail lingering behind. At no less than one minute and up to at least three minutes after the object peaked in intensity (depending on distance from trail), a large concussive blast was heard that shattered windows and set-off car alarms, which was followed by a number of smaller explosions.[52]

- 2019 – Midwestern United States

- On November 11, 2019, a meteor was spotted streaking across the skies of the Midwestern United States. In the St. Louis Area, security cameras, dashcams, webcams, and video doorbells captured the object as it burned up in the earth's atmosphere. The superbolide meteor was part of the South Taurids meteor shower.[53] It traveled east to west ending its flight somewhere near Wellsville, Missouri.[54][55]

Monitoring

[edit]

In a range of countries networks of sky observing installations have been set up to monitor meteors.

Gallery

[edit]-

Orionid meteor

-

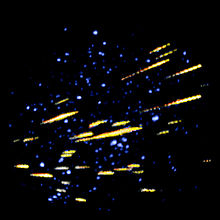

Sporadic bolide over the desert of Central Australia and a Lyrid (top edge)

-

Meteor (center) seen from the International Space Station

-

Possible meteor (center) photographed from Mars, March 7, 2004, by MER Spirit

-

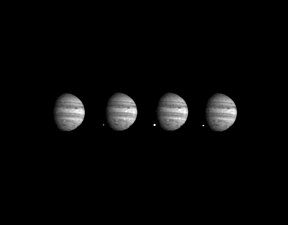

Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 colliding with Jupiter: The sequence shows fragment W turning into a fireball on the planet's dark side

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Cosmic Fireball Falling Over ALMA". ESO Picture of the Week. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ "Glossary International Meteor Organization". International Meteor Organization (IMO). Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ^ a b "meteor". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2014-09-21.

- ^ Bronshten, V. A. (2012). Physics of Meteoric Phenomena. Science. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 358. ISBN 978-94-009-7222-3.

- ^ Bob King. (2016). Night Sky With Naked Eye: How to Find Planets, Constellations, Satellites and Other Night Sky Wonders Without a Telescope[ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^ Erickson, Philip J. "Millstone Hill UHF Meteor Observations: Preliminary Results". Archived from the original on 2016-03-05.

- ^ "Meteor FAQs: How high up do meteors occur?". American Meteor Society (AMS). Retrieved 2021-04-16.

- ^ Subasinghe, Dilini (2018). "Luminous Efficiency Estimates of Meteors". Astronomical Journal. 155 (2): 88. arXiv:1801.06123. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aaa3e0. S2CID 118990427.

- ^ Williams, David R. (2004-09-01). "Earth Fact Sheet". NASA. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

- ^ Jenniskens, Peter (2006). Meteor Showers and their Parent Comets. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 372. ISBN 978-0-521-85349-1.

- ^ Taibi, Richard. "The Early Years of Meteor Observations in the USA". American Meteor Society.

- ^ a b Kronk, Gary W. "The Leonids and the Birth of Meteor Astronomy". Meteorshowers Online. Archived from the original on January 22, 2009.

- ^ Hitchcock, Edward (January 1834). "On the Meteors of Nov. 13, 1833". The American Journal of Science and Arts. XXV.

- ^ "October's Orionid Meteors". Astro Prof. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ Zay, George (1999-07-09). "MeteorObs Explanations and Definitions (states IAU definition of a fireball)". Meteorobs.org. Archived from the original on 2011-10-01. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ^ "International Meteor Organization - Fireball Observations". imo.net. 2004-10-12. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ^ a b Di Martino, Mario; Cellino, Alberto (2004). "Physical properties of comets and asteroids inferred from fireball observations". In Belton, Michael J. S.; Morgan, Thomas H.; Samarasinha, Nalin; et al. (eds.). Mitigation of hazardous comets and asteroids. Cambridge University Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-521-82764-5.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian, ed. (2018). "bolide". Oxford Dictionary of Astronomy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-185119-3. Retrieved 2024-09-03.

- ^ Rogers, John J. W. (1993). A History of the Earth. Cambridge University Press. p. 251. ISBN 978-0-521-39782-7.

- ^ "Bolide". MyEtymology. Archived from the original on January 17, 2012.

- ^ Adushkin, Vitaly; Nemchinov, Ivan (2008). Catastrophic events caused by cosmic objects. Springer. p. 133. Bibcode:2008cecc.book.....A. ISBN 978-1-4020-6451-7.

- ^ a b American Meteor Society. "Fireball Logs". Retrieved 2016-09-28.

- ^ "Fireball FAQs". American Meteor Society. Retrieved 2013-03-21.

- ^ Cook, Bill. "NASA's All Sky Fireball Network". Retrieved 2021-03-04.

- ^ Kanipe, Jeff (14 September 2006). "Climate change: A cosmic connection". Nature. 443 (7108): 141–143. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..141K. doi:10.1038/443141a. PMID 16971922. S2CID 4400113.

- ^ "Fireballs and Meteorite Falls". International Meteor Organization. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- ^ "Fireball FAQS". American Meteor Society. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- ^ "Background facts on meteors and meteor showers". NASA. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- ^ Burdick, Alan (2002). "Psst! Sounds like a meteor: in the debate about whether or not meteors make noise, skeptics have had the upper hand until now". Natural History. Archived from the original on 2012-07-15.

- ^ Zgrablić, Goran; Vinković, Dejan; Gradečak, Silvija; Kovačić, Damir; Biliškov, Nikola; Grbac, Neven; Andreić, Željko; Garaj, Slaven (2002). "Instrumental recording of electrophonic sounds from Leonid fireballs". Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics. 107 (A7): SIA 11–1–SIA 11-9. Bibcode:2002JGRA..107.1124Z. doi:10.1029/2001JA000310. ISSN 2156-2202.

- ^ Vaivads, Andris (2002). "Auroral Sounds". Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- ^ "Auroral Acoustics". Laboratory of Acoustics and Audio Signal Processing, Helsinki University of Technology. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ^ Silverman, Sam M.; Tuan, Tai-Fu (1973). Auroral Audibility. Advances in Geophysics. Vol. 16. pp. 155–259. Bibcode:1973AdGeo..16..155S. doi:10.1016/S0065-2687(08)60352-0. ISBN 978-0-12-018816-1.

- ^ Keay, Colin S. L. (1990). "C. A. Chant and the Mystery of Auroral Sounds". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 84: 373–382. Bibcode:1990JRASC..84..373K.

- ^ "Listening to Leonids". science.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 2009-09-08. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ^ Sommer, H. C.; Von Gierke, H. E. (September 1964). "Hearing sensations in electric fields". Aerospace Medicine. 35: 834–839. PMID 14175790. Extract text archive.

- ^ Frey, Allan H. (1 July 1962). "Human auditory system response to modulated electromagnetic energy". Journal of Applied Physiology. 17 (4): 689–692. doi:10.1152/jappl.1962.17.4.689. PMID 13895081. S2CID 12359057. Full text archive.

- ^ Frey, Allan H.; Messenger, Rodman (27 Jul 1973). "Human Perception of Illumination with Pulsed Ultrahigh-Frequency Electromagnetic Energy". Science. 181 (4097): 356–358. Bibcode:1973Sci...181..356F. doi:10.1126/science.181.4097.356. PMID 4719908. S2CID 31038030. Full text archive.

- ^ Riley, Chris (1999-04-21). "Sound of shooting stars". BBC News. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ^ Whipple, Fred (1951). "A Comet Model. II. Physical Relations for Comets and Meteors". Astrophysical Journal. 113: 464–474. Bibcode:1951ApJ...113..464W. doi:10.1086/145416.

- ^ Phillips, Tony. "Spring is Fireball Season". science.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 2011-04-03. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ^ Langbroek, Marco; Seizoensmatige en andere variatie in de valfrequentie van meteorieten, Radiant (Journal of the Dutch Meteor Society), 23:2 (2001), p. 32

- ^ Coulter, Dauna (2011-03-01). "What's Hitting Earth?". science.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-05-25. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ^ "The Peekskill Meteorite October 9". aquarid.physics.uwo.ca.

- ^ Brown, Peter; Ceplecha, Zedenek; Hawkes, Robert L.; Wetherill, George W.; Beech, Martin; Mossman, Kaspar (1994). "The orbit and atmospheric trajectory of the Peekskill meteorite from video records". Nature. 367 (6464): 624–626. Bibcode:1994Natur.367..624B. doi:10.1038/367624a0. S2CID 4310713.

- ^ Wlotzka, Frank (1993). "The Meteoritical Bulletin, No. 75, 1993 December". Meteoritics. 28 (5): 692–703. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.1993.tb00641.x.

- ^ Yeomans, Donald K.; Chodas, Paul; Chesley, Steve (October 23, 2009). "Asteroid Impactor Reported over Indonesia". NASA/JPL Near-Earth Object Program Office. Archived from the original on October 26, 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-30.

- ^ "W. L. Eccles Observatory, November 18, 2009, North Camera". YouTube. 2009-11-18. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ^ "W. L. Eccles Observatory, November 18, 2009, North West Camera". YouTube. 2009-11-18. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ^ Yeomans, Don; Chodas, Paul (1 March 2013). "Additional Details on the Large Fireball Event over Russia on Feb. 15, 2013". NASA/JPL Near-Earth Object Program Office. Archived from the original on 6 March 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ JPL (2012-02-16). "Russia Meteor Not Linked to Asteroid Flyby". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ^ "Meteorite slams into Central Russia injuring 1100 - as it happened". Guardian. 15 February 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ Staff (November 12, 2019). "Once in a lifetime: Bright meteor streaks across St. Louis nighttime skies". St. Louis Post Dispatch. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ^ Perlerin, Vincent (12 November 2019). "Fireball spotted over Missouri on Nov. 11th, 2019". American Meteor Society. Retrieved 2024-09-19.

- ^ Elizabeth Wolfe; Saeed Ahmed (November 12, 2019). "A bright meteor streaks through the Midwest sky". CNN. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ^ Reyes, Tim (17 November 2014). "We are not Alone: Government Sensors Shed New Light on Asteroid Hazards". Universe Today. Retrieved 12 April 2015.