Alpha-thalassemia

| Alpha-thalassemia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | α-thalassemia |

| Specialty | Hematology |

| Symptoms | Anemia, jaundice, enlarged spleen[1] |

| Complications | Iron overload |

| Usual onset | Inherited - present in utero |

| Causes | Genetically determined deficiency in alpha globin production[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood smear, hemoglobin electrophoresis, DNA sequencing[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Beta thalassemia, iron deficiency anemia |

| Treatment | Blood transfusion, possible splenectomy, bone marrow transplant[1][4] |

Alpha-thalassemia (α-thalassemia, α-thalassaemia) is an inherited blood disorder and a form of thalassemia. Thalassemias are a group of inherited blood conditions which result in the impaired production of hemoglobin, the molecule that carries oxygen in the blood.[5] Symptoms depend on the extent to which hemoglobin is deficient, and include anemia, pallor, tiredness, enlargement of the spleen, iron overload, abnormal bone structure, jaundice, and gallstones. In severe cases death ensues, often in infancy, or death of the unborn fetus.[6][7]

The disease is characterised by reduced production of the alpha-globin component of hemoglobin, caused by inherited mutations affecting the genes HBA1 and HBA2.[8] This causes reduced levels of hemoglobin leading to anemia, while the accumulation of surplus beta-globin, the other structural component of hemoglobin, damages red blood cells and shortens their life.[6] Diagnosis is by checking the medical history of near relatives, microscopic examination of blood smear, ferritin test, hemoglobin electrophoresis, and DNA sequencing.[6]

As an inherited condition, alpha thalassemia cannot be prevented although genetic counselling of parents prior to conception can propose the use of donor sperm or eggs.[9] The principle form of management is blood transfusion every 3 to 4 weeks, which relieves the anemia but leads to iron overload and possible immune reaction. Medication includes folate supplementation, iron chelation, bisphosphonates, and removal of the spleen.[6] Alpha thalassemia can also be treated by bone marrow transplant from a well matched donor.[10]

Thalassemias were first identified in severely sick children in 1925,[11] with identification of alpha and beta subtypes in 1965.[12] Alpha thalassemia is has greatest prevalence in populations originating from Southeast Asia, Mediterranean countries, Africa, the Middle East, India, and Central Asia.[8] Having a mild form of alpha thalassemia has been demonstrated to protect against malaria and thus can be an advantage in malaria endemic areas.[13]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]The presentation of individuals with alpha-thalassemia consists of:

| Common | Uncommon |

|---|---|

|

|

Cause

[edit]

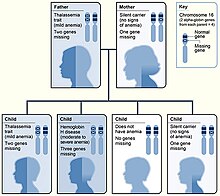

Alpha-thalassemias are most commonly inherited in a Mendelian recessive manner. They are also associated with deletions of chromosome 16p.[2] Alpha thalassemia can also be acquired under rare circumstances.[17]

Pathophysiology

[edit]

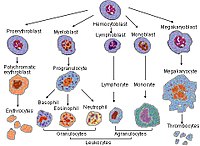

Hemoglobin is a protein containing iron that facilitates the transportation of oxygen in red blood cells.[18] Hemoglobin in the blood carries oxygen from the lungs to the other tissues of the body, where it releases the oxygen to enable metabolism. A healthy level of hemoglobin for men is between 13.2 and 16.6 grams per deciliter, and in women between 11.6 and 15 g/d.[19]

Normal adult hemoglobin (HbA) is composed of four protein chains, two α and two β-globin chains arranged into a heterotetramer. In thalassemia, patients have defects in the noncoding region of either the α or β-globin genes, causing ineffective production of normal alpha- or beta-globin chains, which can lead to ineffective erythropoiesis, premature red blood cell destruction, and anemia.[20] The thalassemias are classified according to which chain of the hemoglobin molecule is affected. In α-thalassemias, production of the α-globin chain is affected, while in β-thalassemia, production of the β-globin chain is affected.[21]

The α-globin chains are encoded by two closely linked genes HBA1[22] and HBA2[23] on chromosome 16; in a person with two copies on each chromosome, a total of four loci encode the α chain.[24] Two alleles are maternal and two alleles are paternal in origin. Alpha-thalassemias result in decreased alpha-globin production, resulting in an excess of β chains in adults and excess γ chains in fetus and newborns.

- In infants and adults, the excess β chains form unstable tetramers called hemoglobin H or HbH comprising 4 beta chains.

- In the fetus, the excess γ chains combine hemoglobin Bart's comprising 4 gamma chains

Both HbH and Hb Bart's have a strong affinity for oxygen but do not release it, causing oxygen starvation in the tissues. They can also precipitate within the RBC damaging its membrane and shortening the life of the cell.[25]

The severity of the α-thalassemias is correlated with the number of affected α-globin alleles: the greater, the more severe will be the manifestations of the disease.[26][27]

| # of faulty alleles | Types of alpha thalassemia[26][27] | Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Silent carrier | No symptoms |

| 2 | Alpha thalassemia trait | Minor anemia |

| 3 | Hemoglobin H disease | Mild to moderate anemia; may lead normal life |

| 4 | Hemoglobin Bart’s hydrops fetalis | Death usually occurs in utero or at birth |

Diagnosis

[edit]Diagnosis of alpha-thalassemia is primarily by laboratory evaluation and molecular diagnosis. Alpha-thalassemia can be mistaken for iron-deficiency anaemia on a full blood count or blood film, as both conditions have a microcytic anaemia. Serum iron and serum ferritin can be used to exclude iron-deficiency anaemia.[3]

Laboratory diagnosis

[edit]The ability to measure hemoglobin Barts makes it useful in newborn screening tests. If hemoglobin Barts is detected on a newborn screen, the patient is usually referred for further evaluation since detection of hemoglobin Barts can indicate either one alpha globin gene deletion, making the baby a silent alpha thalassemia carrier, two alpha globin gene deletions (alpha thalassemia), or hemoglobin H disease (three alpha globin gene deletions).[citation needed]

Post-newborn ages, initial laboratory diagnosis should include a complete blood count and red blood cell indices.[7] As well, a peripheral blood smear should be carefully reviewed.[7] In hemoglobin H disease, red blood cells containing hemoglobin H inclusions can be visualized on the blood smear using new methylene blue or brilliant cresyl blue stain.[28]

Hemoglobin analysis is important for the diagnosis of alpha-thalassemia as it determines the types and percentages of types of hemoglobin present.[29] Several different methods of hemoglobin analysis exist, including hemoglobin electrophoresis, capillary electrophoresis and high-performance liquid chromatography.[29]

Molecular analysis of DNA sequences (DNA analysis) can be used for the confirmation of a diagnosis of alpha-thalassemia, particularly for the detection of alpha-thalassemia carriers (deletions or mutations in only one or two alpha-globin genes).[29]

Prognosis

[edit]Deletion of four alpha globin genes was previously felt to be incompatible with life, but there are currently[when?] 69 patients who have survived past infancy. All such children too show high level of hemoglobin Barts on newborn screen along with other variants.[30]

Treatment

[edit]Treatment for alpha-thalassemia may include blood transfusions to maintain hemoglobin at a level that reduces symptoms of anemia. The decision to initiate transfusions depends on the clinical severity of the disease.[31] Splenectomy is a possible treatment option to increase total hemoglobin levels in cases of worsening anemia due to an overactive or enlarged spleen, or when transfusion therapy is not possible.[32] However, splenectomy is avoided when other options are available due to an increased risk of serious infections and thrombosis.[32]

Additionally, gallstones may be a problem that would require surgery. Secondary complications from febrile episode should be monitored, and most individuals live without any need for treatment.[1][4] Additionally, stem cell transplantation should be considered as a treatment (and cure), which is best done in early age. Other options, such as gene therapy, are still being developed.[33]

A study by Kreger et al combining a retrospective review of three cases of alpha thalassemia major and a literature review of 17 cases found that in utero transfusion can lead to favorable outcomes. Successful hematopoietic cell transplantation was eventually carried out in four patients.[34]

Epidemiology

[edit]

Worldwide distribution of inherited alpha-thalassemia corresponds to areas of malaria exposure, suggesting a protective role. Thus, alpha-thalassemia is common in sub-Saharan Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, and generally tropical (and subtropical) regions. The epidemiology of alpha-thalassemia in the US reflects this global distribution pattern. More specifically, HbH disease is seen in Southeast Asia and the Middle East, while Hb Bart hydrops fetalis is acknowledged in Southeast Asia only.[35] The data indicate that 15% of the Greek and Turkish Cypriots are carriers of beta-thalassemia genes, while 10% of the population carry alpha-thalassemia genes.[36]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Origa, Raffaella; Moi, Paolo; Galanello, Renzo; Cao, Antonio (1 January 1993). "Alpha-Thalassemia". GeneReviews. PMID 20301608. Archived from the original on 4 September 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2016.update 2013

- ^ a b BRS Pathology (4th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins medical. December 2009. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-4511-1587-1.

- ^ a b "Alpha Thalassemia Workup: Approach Considerations, Laboratory Studies, Hemoglobin Electrophoresis". emedicine.medscape.com. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ a b "Complications and Treatment | Thalassemia | Blood Disorders | NCBDDD | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ Lanzkowsky's Manual Of Pediatric Hematology And Oncology 6th Edition ( 2016).

- ^ a b c d "Alpha Thalassemia". John Hopkins Medicine. 27 January 2025. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f "Alpha-thalassemia - Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment | BMJ Best Practice". bestpractice.bmj.com. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Alpha thalassemia: MedlinePlus Genetics". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ "Thalassaemia - Thalassaemia carriers". National Health Service. 17 October 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ England, N. H. S. (10 November 2023). "NHS England » Clinical commissioning policy: allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (Allo-HSCT) for adult transfusion dependent thalassaemia". www.england.nhs.uk. Retrieved 18 January 2025.

- ^ Stuart H. Orkin; David G. Nathan; David Ginsburg; A. Thomas Look (2009). Nathan and Oski's Hematology of Infancy and Childhood, Volume 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 1054–1055. ISBN 978-1-4160-3430-8.

- ^ Harteveld, Cornelis L.; Higgs, Douglas R. (28 May 2010). "α-thalassaemia". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 5 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-5-13. ISSN 1750-1172. PMC 2887799. PMID 20507641.

- ^ Wambua S, Mwangi TW, Kortok M, Uyoga SM, Macharia AW, Mwacharo JK, Weatherall DJ, Snow RW, Marsh K, Williams TN (May 2006). "The effect of alpha+-thalassaemia on the incidence of malaria and other diseases in children living on the coast of Kenya". PLOS Medicine. 3 (5): e158. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030158. PMC 1435778. PMID 16605300.

- ^ Reference, Genetics Home. "Alpha thalassemia". Genetics Home Reference. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ Origa, Raffaella; Moi, Paolo (1993), Adam, Margaret P.; Ardinger, Holly H.; Pagon, Roberta A.; Wallace, Stephanie E. (eds.), "Alpha-Thalassemia", GeneReviews®, University of Washington, Seattle, PMID 20301608, archived from the original on 12 November 2020, retrieved 25 November 2019

- ^ "Assessment of anaemia - Aetiology | BMJ Best Practice". bestpractice.bmj.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ Steensma DP, Gibbons RJ, Higgs DR (January 2005). "Acquired alpha-thalassemia in association with myelodysplastic syndrome and other hematologic malignancies". Blood. 105 (2): 443–52. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-07-2792. PMID 15358626.

- ^ Maton, Anthea; Jean Hopkins; Charles William McLaughlin; Susan Johnson; Maryanna Quon Warner; David LaHart; Jill D. Wright (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, US: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-981176-0.

- ^ "Hemoglobin test - Mayo Clinic". Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. 12 April 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2025.

- ^ Baird DC, Batten SH, Sparks SK. Alpha- and Beta-thalassemia: Rapid Evidence Review. Am Fam Physician. 2022 Mar 1;105(3):272-280. PMID 35289581.

- ^ Muncie HL, Campbell J (August 2009). "Alpha and beta thalassemia". American Family Physician. 80 (4): 339–344. PMID 19678601.

- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): Hemoglobin—Alpha locus 1; HBA1 - 141800

- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): Hemoglobin—Alpha locus 2; HBA2 - 141850

- ^ Robbins Basic Pathology, Page No:428

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Harewood-2023was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Galanello R, Cao A (February 2011). "Gene test review. Alpha-thalassemia". Genetics in Medicine. 13 (2): 83–88. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181fcb468. PMID 21381239.

- ^ a b "Alpha-thalassaemia". Genomics Education Programme, NHS England. 24 August 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2025.

- ^ Keohane, E; Smith, L; Walenga, J (2015). Rodak's Hematology: Clinical Principles and Applications (5 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 466. ISBN 978-0-323-23906-6. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Viprakasit, Vip; Ekwattanakit, Supachai (1 April 2018). "Clinical Classification, Screening and Diagnosis for Thalassemia". Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America. 32 (2): 193–211. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2017.11.006. ISSN 0889-8588. PMID 29458726.

- ^ Songdej D, Babbs C, Higgs DR (March 2017). "An international registry of survivors with Hb Bart's hydrops fetalis syndrome". Blood. 129 (10): 1251–1259. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-08-697110. PMC 5345731. PMID 28057638.

- ^ "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ a b Taher, Ali; Musallam, Khaled; Cappellini, Maria Domenica, eds. (2017). Guidelines for the management of non-transfusion-dependent thalassemia (NTDT) (2nd ed.). Thalassemia International Foundation. pp. 24–32. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ "Thalassaemia | Doctor | Patient". Patient. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ Kreger EM, Singer ST, Witt RG, Sweeters N, Lianoglou B, Lal A, et al. (December 2016). "Favorable outcomes after in utero transfusion in fetuses with alpha thalassemia major: a case series and review of the literature". Prenatal Diagnosis. 36 (13): 1242–1249. doi:10.1002/pd.4966. PMID 27862048. S2CID 29734120.

- ^ Harteveld CL, Higgs DR (May 2010). "Alpha-thalassaemia". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 5 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-5-13. PMC 2887799. PMID 20507641.

- ^ Haematology Made Easy. AuthorHouse. 2013-02-06. ISBN 978-1-4772-4651-1.page 246

Further reading

[edit]- Anie KA, Massaglia P (March 2014). "Psychological therapies for thalassaemia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (3): CD002890. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd002890.pub2. PMC 7138048. PMID 24604627.

- Galanello R, Cao A (February 2011). "Gene test review. Alpha-thalassemia". Genetics in Medicine. 13 (2): 83–8. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181fcb468. PMID 21381239. S2CID 209070781.

External links

[edit]- "What Are Thalassemias? - NHLBI, NIH". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. Retrieved 15 September 2016.