ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's journeys to the West

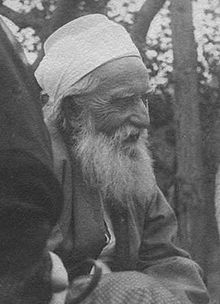

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's journeys to the West were a series of trips ʻAbdu'l-Bahá undertook starting at the age of 66, journeying continuously from Palestine to the West between 1910 and 1913. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was the eldest son of Baháʼu'lláh, founder of the Baháʼí Faith, and suffered imprisonment with his father starting at the age of 8; he suffered various degrees of privation for almost 55 years, until the Young Turk Revolution[1] in 1908 freed religious prisoners of the Ottoman Empire. Upon the death of his father in 1892, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá had been appointed as the successor, authorized interpreter of Bahá'u'lláh's teachings, and Center of the Covenant of the Baháʼí Faith.

At the time of his release, the major centres of Baháʼí population and scholarly activity were mostly in Iran,[2] with other large communities in Baku, Azerbaijan,[3] Ashgabat, Turkmenistan,[4] and Tashkent, Uzbekistan.[5]

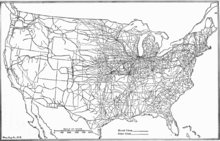

Meanwhile, in the Occident the religion had been introduced in the late 1890s in several locales, with the very first mention of Baha'u'llah occurring in a talk given by a Christian missionary during the First World Parliament of Religions held in conjunction with the Chicago World's Fair in 1893. However, by 1910 the religion's followers still numbered less than a few thousands across the entire West.[2] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá thus took steps to personally present the Baháʼí teachings to the West by traveling to Europe and North America. His first excursion outside of Palestine and Iran was to Egypt in 1910 where he stayed for around a year, followed by a near five-month trip to France and Great Britain in 1911. After returning to Egypt, he left on a trip to North America which lasted nearly eight months. During that trip he visited many cities across the United States, from major metropolitan areas on the eastern coast of the country, to cities in the midwest, and California on the west coast; he also visited Montreal in Canada. Following his trip in North America he visited various countries in Europe, including France, Britain and Germany for six months, followed by a six-month stay again in Egypt, before returning to Haifa.[1]

With his visits to the West, the small Western Baháʼí community was given a chance to consolidate and embrace a wider vision of the religion; the religion also attracted the attention of sympathetic attention from both religious, academic, and social leaders as well as in newspapers which provided significant coverage of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's visits.[6] During his travels ʻAbdu'l-Bahá would give talks at the homes of Baháʼís, at hotels, and at other public and religious sites, such as the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration, the Bethel Literary and Historical Society, at the NAACP, at Howard and Stanford universities, and at various Theosophical Societies, among others. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá talks across the West also became an important addition to the body of Baháʼí literature.[1] In succeeding decades after his visit the American community substantially grew[7] and then spread across South America, Australasia, Subsaharan Africa and the Far East.[8]

During these journeys Bahíyyih Khánum, his sister, was given the position of acting head of the religion.[9]

Trip to Egypt

[edit]ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left Haifa for Port Said, Egypt on 29 August 1910. Earlier on that day he had accompanied two pilgrims to the Shrine of the Báb, and then he headed down to the port in the city where at around 4pm he set sail on the steamer "Kosseur London" and then telegrammed the Baháʼís in Haifa that he was in Egypt.[10][11] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stayed in the city for around one month where Baháʼís from Cairo came to visit him.

On 1 October, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá again set sail; his intention was to go to Europe, but because of his poor health, he instead landed in Alexandria where he stayed for nearly eight months. While in Egypt there was increasingly positive coverage of him and the Baháʼís from various Egyptian news outlets.[10] While in Alexandria he met with a larger number of people. In November he met with Briton Wellesley Tudor Pole who later became a Baháʼí.[12] He also was visited by Russian/Polish Isabella Grinevskaya who also became a Baháʼí.[13] In late April Louis Gregory, an African-American who had gone on Baháʼí pilgrimage, met with ʻAbdu'l-Bahá while he was in the suburb of Ramleh.[14] Later in May ʻAbdu'l-Bahá moved to Cairo and got more favourable press coverage, including from Al-Ahram. During his time there he met the Mufti of Egypt, with Abbas II of Egypt, the Khedive of Egypt.[10]

Finally on 11 August 1911 ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left Egypt towards Europe. He boarded the SS Corsican, an Allan Line Royal Mail Steamer[15][16] towards the port of Marseilles, France accompanied by secretary Mírzá Mahmúd, and personal assistant Khusraw.[17] Memoirs that cover the periods in Egypt include Yazdi (1987).[18]

First trip to Europe

[edit]ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's first European trip spanned from August to December 1911, at which time he returned to Egypt. During his first European trip he visited Lake Geneva on the border of France and Switzerland, Great Britain and Paris, France. The purpose of these trips was to support the Baháʼí communities in the West and to further spread his father's teachings,[19] after sending representatives and a letter to the First Universal Races Congress in July.[20][21]

Various memoirs cover this period.[nb 1]

Lake Geneva

[edit]When ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arrived in Marseille, he was greeted by Hippolyte Dreyfus-Barney, a prominent early French Baháʼí.[22] Dreyfus-Barney accompanied ʻAbdu'l-Bahá to Thonon-les-Bains, a French town, on Lake Geneva that straddles France and Switzerland.[22]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stayed in Thonon-les-Bains in France for a few days before going to Vevey in Switzerland. In Vevey ʻAbdu'l-Bahá offered a talk on the Baháʼí point of view on the immortality of soul and relationship of worlds and on the subject of divorce. He also met Horace Holley there.[23] While in Thonon, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá met Mass'oud Mirza Zell-e Soltan, who had asked to meet ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. Soltan, who had ordered the execution of King and Beloved of martyrs, was the eldest grandson of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar who had ordered the Execution of the Báb himself. Juliet Thompson, an American Baháʼí and artist who had also come to visit ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, shared comments of Hippolyte who heard Soltan's stammering apology for past wrongs. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá embraced him and invited his sons to lunch.[24] Thus Bahram Mirza Sardar Mass'oud and Akbar Mass'oud, another grandson of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, met with the Baháʼís, and apparently Akbar was greatly affected by meeting ʻAbdu'l-Bahá.[25]

Great Britain

[edit]On 3 September ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left the shores of Lake Geneva travelling towards London where he arrived on 4 September; he would stay in London until 23 September. While in London ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stayed at a residence of Lady Blomfield.[26] On the first few days in London ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was interviewed by the editor of the Christian Commonwealth, a weekly newspaper devoted to a liberal Christian theology.[27][28] The editor was also present at a meeting of the Reverend Reginald John Campbell and ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and wrote about the meeting in the 13 September edition of the Christian Commonwealth and the reprinted in the Star of the West Baháʼí magazine.[27] After the meeting, the Reverend Reginald John Campbell asked ʻAbdu'l-Bahá to speak at City Temple.

Later in the month ʻAbdu'l-Bahá took a trip to Byfleet near Surrey where he visited Alice Buckton and Anett Schepel at their home.[17][29][30] On the evening of 10 September he gave his first public talk in the Occident at City Temple[29] The English translation was read by Wellesley Tudor Pole[17] and the talk was printed in the Christian Commonwealth newspaper on 13 September.

On 17 September, at the invitation of Albert Wilberforce, Archdeacon of Westminster, he addressed the congregation of Saint John the Divine, in Westminster.[17] He spoke on the subject of the kingdoms of mineral, vegetable, animal, humanity, and the Manifestations of God beneath God;[29] Albert Wilberforce read the English translation himself.[17] On the 28th ʻAbdu'l-Bahá returned to Byfleet again visiting Buckhorn and Schepel.[29][30] He visited Bristol on the 23rd–25th for several receptions and meetings though less public. On one such meeting he mentioned "When a thought of war enters your mind, suppress it, and plant in its stead a positive thought of peace."[17] On the 30th he spoke to a Theosophical Society meeting with Annie Besant, Alfred Percy Sinnett, Eric Hammond,[17] who later published a volume on the religion in 1909.[31] Back in London Alice Buckton visited Abdu'l-Bahá once again, and he went to Church House, Westminster to see a Christmas mystery play titled Eager Heart that she had written.[17]

From 23 to 25 September, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá went to Bristol where he met with many leading individuals including David Graham Pole, Claude Montefiore, Alexander Whyte, Lady Evelyn Moreton among others.[17] Rev. Peter Z. Easton, a Presbyterian in the Synod of the Northeast in New York who was stationed in Tabriz, Iran from 1873 to 1880, did not have an appointment to meet ʻAbdu'l-Bahá.[32][33] Easton attempted to meet and challenge ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and in his actions made those around him uncomfortable; ʻAbdu'l-Bahá withdrew him to a private conversation and then he left. Later he printed a polemic attack on the religion, Bahaism—A Warning, in the Evangelical Christendom newspaper of London (September–October 1911 edition.)[34] The polemic was later responded to by Mírzá Abu'l-Faḍl in his book The Brilliant Proof written in December 1911.[35]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá returned to London on 25 September, and a pastor of a Congregational church in the east end of London invited him to give an address on the following Sunday evening.[17] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá also visited to Oxford University where he met the higher Bible critic, Thomas Kelly Cheyne. Though ill, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá embraced him and praised his life's work.[17][36] News of his activity in Britain was covered in New Zealand in a couple publications.[37][38][39]

Ezra Pound met with him about the end of September, later explaining to Margaret Craven that Pound approached him like "an inquisition… and came away feeling that questions would have been an impertinence…."[40]

The whole point is that they have done instead of talking, and a persian movement for religious unity that claims the feminine soul equal to the male… is worth while."[40]

On 1 October 1911, he returned to Bristol to perform a wedding of Baháʼís who had traveled from Persia and who brought humble gifts as well.[17][29] On 3 October ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left London for Paris, France.[1]

France

[edit]ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stayed in Paris for nine weeks, during which time he stayed at a residence at 4 Avenue de Camoens, and during his time there he was helped by Mr. Dreyfus-Barney and his wife, along with Lady Blomfield who had come from London. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's first talk in Paris was on 16 October,[41] and later that same day guests gathered in a poor quarter outside Paris at a home for orphans by Mr and Mrs. Ponsonaille which was much praised by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá.[42]

From almost every day from 16 October to 26 November he gives talks.[41][43] On a few of the days, he gave more than one talk. The book Paris Talks, part I, records transcripts of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's talks while he was in Paris for the first time. The substance of the volume is from notes Sara Louisa Blomfield,[44] her two daughters and a friend.[45] While most of his talks were held at his residence, he also gave talks at the Theosophical Society headquarters, at L'Alliance Spiritaliste, and on 26 November he spoke at Charles Wagner's church Foyer de l-Ame.[43] He also met with various people including Muhammad ibn ʻAbdu'l-Vahhad-i Qazvini and Seyyed Hasan Taqizadeh.[46] It was during one of the meetings with Taqizadeh that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá personally first spoke on a telephone.

On 2 December 1911 ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left France, returning to Egypt.[10]

Trip to North America

[edit]

In the following year, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá undertook a much more extensive journey to the United States and Canada, ultimately visiting some 40 cities, to once again spread his father's teachings.[47] He arrived in New York City on 11 April 1912. While he spent most of his time in New York, he visited many cities on the east coast. Then in August he started a more extensive journey across to the West coast before starting to return east at the end of October. On 5 December 1912 he set sail back to Europe.[19] Several people, including ʻAbdu'l-Bahá himself, Allan L. Ward, author of 239 Days, and critic Samuel Graham Wilson have taken note of the uniqueness of this trip.[48][49] Ward wrote: "... never before during the formative years of a religion has a figure of like stature made a journey of such magnitude in a setting so different from that of His native land." Wilson stated: "But Abdul Baha, except for Hindu Swamis, was the first Asiatic revelator America has received. Its hospitality showed up well. The public and press neither stoned the "prophet" nor caricatured him but looked with kindly eye upon the grave old man, in flowing oriental robes and white turban, with waving hoary hair and long white beard."

During his nine months on the continent, he met with David Starr Jordan, president of Stanford University; Rabbi Stephen Samuel Wise of New York City; the inventor Alexander Graham Bell; Jane Addams, the noted social worker; the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore, who was touring America at the time;[50] Herbert Putnam, Librarian of Congress; the industrialist and humanitarian Andrew Carnegie; Samuel Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor; the Arctic explorer Admiral Robert Peary; as well as hundreds of American and Canadian Baháʼís, recent converts to the religion.[51]

A large number of memoirs cover this period[nb 2] as well as a wide array of newspaper stories.[52][53]

On the RMS Cedric

[edit]ʻAbdu'l-Bahá boarded the RMS Cedric in Alexandria, Egypt bound for Naples on 25 March 1912.[1] Others with him included Shoghi Effendi, Asadu'lláh-i-Qumí, Dr Amínu'lláh Faríd, Mírzá Munír-i-Zayn, Áqá Khusraw, and Mahmúd-i-Zarqání.[54] During the voyage a member of the Unitarians onboard requested if ʻAbdu'l-Bahá would send a message to them. He replied with a message announcing "… Glad tidings, glad tidings, the Herald of the Kingdom has raised His voice."[55] Through several conversations it was arranged by several passengers that he address a larger audience on the ship.[56] The ship arrived in Naples harbour on 28 March 1912,[57] and on the next day several Baháʼís from America and Britain boarded the ship. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and his group did not disembark for fear of being confused with Turks during the ongoing Italo-Turkish War. Shoghi Effendi and two others were refused further passage by reason of a minor illness and were taken ashore. Though all were not convinced of the sincerity of the diagnosis and some presumed it was ill will against the voyagers as if they were Turkish.[1]

The American Baháʼí community had sent thousands of dollars urging ʻAbdu'l-Bahá to leave the Cedric in Italy and travel to England to sail on the maiden voyage of the RMS Titanic. Instead he returned the money for charity and continued the voyage on the Cedric.[58] From Naples, the group sailed on to New York — the group included ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, Asadu'lláh-i-Qumí, Dr Amínu'lláh Faríd, Mahmúd-i-Zarqání, Mr and Mrs Percy Woodcock and their daughter from Canada, Mr and Mrs Austin from Denver, Colorado, and Miss Louisa Mathew.[59] Other notables aboard included at least two Italian embassy officials; note ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was listed as an "author" on immigration paperwork.[60] They passed Gibraltar on 3 April onward to New York.[61] Many letters and telegrams were sent and received during the voyage as well as various tablets written.

New England

[edit]The SS Cedric arrived in New York harbour on the morning of 11 April and telegrams were sent and received from Baháʼí local spiritual assemblies to announce his safe arrival while the passengers were processed for quarantine.[62] Baháʼís who had gathered at the port were generally sent to gather at a home where ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was to visit later. Reporters interviewed him while he was on board and he elaborated on the trip and his goals. However a few Baháʼís, including Marjorie Morten, Rhoda Nichols and Juliet Thompson, hid themselves to catch a glimpse of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá.[63] His arrival in New York was covered by various different newspapers including the New York Tribune[64] and the Washington Post.[65]

While in New York he stayed at The Ansonia hotel.[66] Several blocks to the north west of the hotel was the residence of Edward B. Kinney, where ʻAbdu'l-Bahá held his first meeting with the American Baháʼís;[67] his next talk was at given at Howard MacNutt's residence. From 11 April until 25 April he gave at least one talk a day and most mornings and afternoons were spent meeting often one by one with visitors coming to his residence.[54][68][69] During ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's time in New York, Lua Getsinger helped correspond with various Baháʼís about ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's plans as they evolved.[70]

Rev. Percy Stickney Grant, through association with Juliet Thompson, invited ʻAbdu'l-Bahá to speak at Church of the Ascension on the evening of 14 April.[68] The event was covered by the New York Times,[71] the New York Tribune,[72] and the Washington Post.[73] The event caused a stir because, while there were rules in the Episcopal Church Canon forbidding someone of another ordination from preaching from the pulpit without the consent of the bishop, there was no provision against a non-ordained person offering prayer in the chancel.[74]

Mary Williams, also known as Kate Carew, known for her caricatures,[75] was among those who visited ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and travelled with him for a number of days. On 16 April, with Mary Williams still travelling with him, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá visited the Bowery.[76] Mary Williams noted that she was impressed with ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's generosity of spirit in bringing people of social standing to the Bowery as well as that he then gave money to the poor.[58][76][77][78] Some boys were reported to heckle the event but were invited afterwards for a personal meeting. At this meeting, after greeting all the boys, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá singled out an African-American boy and compared him to a black rose as well as rich chocolate.[79]

In Boston newspaper reporters asked ʻAbdu'l-Bahá why he had come to America, and he stated that he had come to participate in conferences on peace and that just giving warning messages is not enough.[80] A full page summary of the religion was printed in the New York Times.[81] A booklet on the religion was published late April.[82]

On 20 April ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left New York and travelled to Washington, D.C., where he stayed until 28 April. While in Washington, D.C., a number of meetings and notable events took place. On 23 April ʻAbdu'l-Bahá attended several events;[83] first he spoke at Howard University to over 1000 students, faculty, administrators and visitors—an event commemorated in 2009.[84] Then he attended a reception by the Persian Charg-de-Affairs and the Turkish Ambassador;[85] at this reception ʻAbdu'l-Bahá moved the place-names such that the only African-American present, Louis George Gregory, was seated at the head of the table next to himself.[85][86][87][88] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá also welcomed William Sulzer, then a Democratic Congressman and later Governor from New York, as well as Champ Clark, then Speaker of the House of Representatives.[89][nb 3]

Later during his stay in Washington, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá spoke at Bethel Literary and Historical Society, the leading African-American institution of Washington DC.[90] The talk had been planned out by the end of March due to the work of Louis Gregory.[85][91][92] While in Washington ʻAbdu'l-Bahá continued to speak from the Parson's home to individuals and groups.[93] A Methodist minister suggested some of his listeners should teach him Christianity, though also judged him sincere.[94]

Midwest

[edit]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arrived in Chicago on 29 April,[1] though later than anticipated as he had hoped to be in Chicago in time for the American Baháʼí national convention.[95] While in Chicago ʻAbdu'l-Bahá attended the last session of the newly founded Baháʼí Temple Unity, and laid the dedication stone of the Baháʼí House of Worship near Chicago.[96]

Robert Sengstacke Abbott, an African American lawyer and newspaper publisher, met ʻAbdu'l-Bahá when covering a talk of his during his stay in Chicago at Jane Addams' Hull House.[97] He would later become a Baháʼí in 1934.[98] Also while ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was in Chicago, the NAACP's print magazine The Crisis printed an article introducing the religion to their readers,[99] and later in June noted ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's talk at their fourth national convention.[100][101][102]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left Chicago on 6 May and went to Cleveland where he stayed until the 7th. Though Saichiro Fujita, one of the first Baháʼís of Japanese descent, was living in Cleveland working for a Dr Barton-Peek, a female Baháʼí, he failed to meet ʻAbdu'l-Bahá as he came through. He was able to meet ʻAbdu'l-Bahá later during his further travels.[103] In Cleveland ʻAbdu'l-Bahá spoke at his hotel twice and was interviewed by newspaper reporters.[104][105] Among some who met ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in Cleveland included Louise Gregory,[106] and Alain Locke.[107]

On 7 May ʻAbdu'l-Bahá went to Pittsburgh where a speaking engagement was arranged for him in early April through the efforts of Martha Root.[108][109] He stayed in Pittsburgh for one day before going back to Washington D.C on 8 May 1912.

Back to North East

[edit]

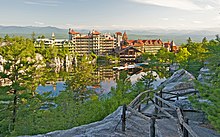

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stayed in Washington DC from 8 to 11 May, when he then returned to the New York City area. On 12 May he visited Montclair, NJ, and then on 14 May he went to northern New York state to Lake Mohonk where he addressed the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration and stayed at the Mohonk Mountain House.[110][111][112][113][114][115]

His talk was covered by many publications,[58][116][117][118][119] and began

"When we consider history, we find that civilization is progressing, but in this century its progress cannot be compared with that of past centuries. This is the century of light and of bounty. In the past, the unity of patriotism, the unity of nations and religions was established; but in this century, the oneness of the world of humanity is established; hence this century is greater than the past."[114]

In the rest of his talk he outlined a brief history of religious conflict, spoke about some of the Baháʼí teachings including the oneness of humanity, the complementary role of religion and science, the equality of women and men, the abolition of the extremes of wealth and poverty, and that humanity needs more than philosophy—that it needs the breadth of the Holy Spirit. A reverend heard his presentation and invited him and introduced him at a reception at another event on 28 May.[120][121] Elbert Hubbard, an American writer, also noted ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's talk at the Mohonk conference.[122] Samuel Chiles Mitchell, then President at the University of South Carolina was present and affected by his presentation.[123] Through correspondence with Gregory, Gregory came to the view that Mitchell had repeated ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's words "upon many platforms."

After the conference, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá returned to New York City, where he stayed until the 22nd, leaving to the Boston area for four days including a trip to Worcester, Massachusetts on the 23rd. On 26 May he returned to New York City, where he would remain for most of his time until 20 June. He took short trips to Fanwood, New Jersey, from 31 May to 1 June, to Milford, Pennsylvania, on 3 June, and to Philadelphia from 8 to 10 June, always returning to New York City.[1]

On 18 June ʻAbdu'l-Bahá hosted a meeting at the MacNutt's home for the purpose of being filmed and recorded. This film was the second time that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was filmed,[nb 4] and was done by Baháʼís at the home of Howard MacNutt.[124] The film recorded at the MacNutt residence was released as a short movie called "Servant of Glory".[58][125]

Over several days starting on 1 June ʻAbdu'l-Bahá sat for a life-sized portrait by Juliet Thompson.[58][126] During that time Thompson witnessed Lua Getsinger given the task of conveying ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's message that New York was the City of the Covenant;[127] when the group moved into the rest of the house Getsinger made the announcement.

Later in the month, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá visited Montclair, New Jersey from 20 to 25 June,[128] coming back to New York until 29 June. On 29 and 30 June he visited West Englewood, NJ which is now Teaneck and attended a Unity Feast similar to a Nineteen Day Feast[129][130][131] where Baháʼís, Jews, Muslims, Christians, Caucasians, African-Americans, and Persians attended.[125][132] Among those that attended the event was Martha Root.[109] For her it was a high point in her life and has since been commemorized as ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's "Souvenir Picnic".[133] It is at this event that Lua Getsinger intentionally walked through poison ivy hoping to make her incapable of leaving the presence of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá when he asked her to travel ahead of him to California.[68][134] Today the property is known as the Wilhelm Baháʼí Properties.[58]

His further travels took him to Morristown, New Jersey on 30 June and he then went back to New York for a nearly a month from 30 June to 23 July, with a sojourn in West Englewood, NJ on 14 July. Starting on 23 June ʻAbdu'l-Bahá went to New England on his way to Canada in late August. He stayed in Boston for 23 and 24 July, and then went to the summer home of Mr. and Mrs. Parsons in Dublin, New Hampshire from 24 July to 16 Aug.[135] He then went to Eliot, Maine from 16 to 23 Aug, where he stayed in Green Acre which was then a conference facility, and which since has become a Baháʼí school.[136][137] His final destination in New England was Malden, Massachusetts where he stayed from 23 to 29 August.[1]

Trip to Canada

[edit]ʻAbdu'l-Bahá had mentioned an intention of visiting Montreal as early as February 1912 and in August a phone number was listed for inquirers to arrange appointments for his visit there. He left to Boston and then rode to Montreal where he arrived near midnight on 30 August 1912 at the Windsor train station on Peel Street and was greeted by William Sutherland Maxwell. He would stay in Montreal until 9 September. On his first day in the city he was visited by Frederick Robertson Griffin who would later lead the First Unitarian Church of Philadelphia. Later that morning he visited a friend of the Maxwell's who had a sick baby. In the afternoon he took a car ride around Montreal. That evening a reception was held including a local socialist leader. The next day he spoke at a Unitarian church on Sherbrooke Street. Anne Savage recorded that she had sought him out but uncharacteristically was shy upon seeing him.[138] He took up residence in the Windsor Hotel. The next day William Peterson, then Principal of McGill University visited him. After a day of meeting individuals he took an afternoon excursion on his own possibly to the francophone part of the city and back. That evening he spoke to a socialist meeting addressing "The Economic Happiness of the Human Race"—that we are as one family and should care for each other, not to have absolute equality but to have a firm minimum even for the poorest, to note foremost the position of the farmer, and a progressive tax system.[139] The next day he rode the Mountain Elevator of Montreal The next day Paul Bruchési Archbishop of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Montreal visited him and later he spoke at the Saint James United Church; his talk outlined a comprehensive review of the Baháʼí teachings. Afterwards he said:

I find these two great American nations highly capable and advanced in all that appertains to progress and civilization. These governments are fair and equitable. The motives and purposes of these people are lofty and inspiring. Therefore, it is my hope that these revered nations may become prominent factors in the establishment of international peace and the oneness of the world of humanity; that they may lay the foundations of equality and spiritual brotherhood among mankind; that they may manifest the highest virtues of the human world, revere the divine lights of the Prophets of God and establish the reality of unity so necessary today in the affairs of nations. I pray that the nations of the East and West shall become one flock under the care and guidance of the divine Shepherd. Verily, this is the bestowal of God and the greatest honor [sic] of man. This is the glory of humanity. This is the good pleasure of God. I ask God for this with a contrite heart.[140]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's visit to Montreal provided notable newspaper coverage; on the night of his arrival the editor of the Montreal Daily Star met with him and that newspaper along with The Montreal Gazette, Montreal Standard, Le Devoir and La Presse among others reported on ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's activities.[141][142] The headlines in those papers included "Persian Teacher to Preach Peace", "Racialism Wrong, Says Eastern Sage, Strife and War Caused by Religious and National Prejudices", and "Apostle of Peace Meets Socialists, Abdul Baha's Novel Scheme for Distribution of Surplus Wealth."[142] The Montreal Standard, which was distributed across Canada, took so much interest that it republished the articles a week later; the Gazette published six articles and Montreal's largest French language newspaper published two articles about him.[141] The Harbor Grace Standard newspaper, of Harbour Grace, Newfoundland, printed a story summarizing several of his talks and trips.[143] After he left the country, the Winnipeg Free Press highlighted his position on the equality of women and men.[144] All together some accounts of his talks and trips would reach 440,000 in French and English coverage.[145] He travelled through several villages on the way back to the States.[146]

Travel to the West coast

[edit]ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left Canada and started his travel to the American West coast stopping in multiple places in the country during his travels. From 9 September through 12th he stayed in Buffalo, New York, where he made a fleeting visit to Niagara Falls on 12 September.[147] He then travelled to Chicago (12–15 September), Kenosha, Wisconsin (15–16 September), back to Chicago on 16 September, and then to Minneapolis where he stayed from 16 to 21 September.

His further travels took him to Omaha, Nebraska (21 September), Lincoln, Nebraska (23 September), Denver, Colorado ( 24–27 September), Glenwood Springs, Colorado (28 September), and Salt Lake City (29–30 September).[148][149] In Salt Lake City, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, accompanied by his translators, Saichiro Fujita and others attended the Utah State Fair and visited the Mormon Tabernacle. During the Mormon's annual convention, at the steps of the Temple, he was reported to have said: "They built me a temple but they will not let me in!" He left the next day and travelled by railcar to San Francisco, on what was then the Central Pacific Railroad, through Reno. Traveling all day through Nevada on its way to California, the train made regular stops but there's no record of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá disembarking until his arrival in San Francisco. While traversing the Sierra Nevada, he made a reference to observing the snow sheds at Donner Pass and the struggle of the pioneering members of the Donner Party.

California

[edit]ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arrived in San Francisco on 4 October.[150][151] During his visit to California he mostly stayed in Bay Area including from 4–13 October, 16–18 October, 21–25 October with shorter trips to Pleasanton from 13 to 16 October, to Los Angeles from 18–21 October and to Sacramento from 25–26 October While in San Francisco, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá spoke at Stanford University on 8 October, and at Temple Emmanuel-El on 12 October.

When ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arrived in Los Angeles he went to the Hotel Lankershim, where he would reside during his stay, and where he would later give a talk.[152][nb 5] On his first full day in Los Angeles ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, along with twenty-five other Baháʼís, visited Thornton Chase's grave on 19 October. Thornton Chase was the first American Baháʼí, and he had only recently moved to Los Angeles and helped form the first Local Spiritual Assembly in the city.[155] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was eager to meet Thornton Chase, but Chase died on the evening of 30 September shortly before ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arrived in California on 4 October. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá designated Chase's grave a place of pilgrimage, and revealed a tablet of visitation, which is a prayer to say in remembrance of a person, and decreed that his death be commemorated annually.[156]

Back across America

[edit]After his visit to California, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá started his trip back to the East coast. On his way back he stopped in Denver (28–29 October), Chicago (31 October – 3 November) and Cincinnati (5–6 November) before arriving in Washington, D.C., on 6 November. In Washington he was invited to speak to the Washington Hebrew Congregation at their temple on 9 November.[157]

Later on 11 November, he travelled to Baltimore, where his arrival was anticipated from early April,[158] and he spoke at a Unitarian church saying in part that "the world looked to America as the leader in the world-wide peace movement" and "not being a rival of any other power and not considering colonization schemes or conquests, made it an ideal country to lead the movement."[159][160] On the same day he travelled to Philadelphia, and the next day on 12 November he arrived back to New York where he stayed until he would leave back to Europe 5 December. During his stay in New York ʻAbdu'l-Bahá addressed a suffragette group elaborating on the equality of women and men.[161]

On 5 December ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left New York, sailing for Liverpool on the SS Celtic(as it was named at the time).[162][163]

Second trip to Europe

[edit]ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arrived in Liverpool on 13 December,[164] and over the next six months he visited Britain, France, Austria-Hungary, and Germany before finally returning to Egypt on 12 June 1913.[19]

Several memoirs cover this period.[nb 6]

Great Britain

[edit]After his arrival in Liverpool ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stayed in the city for three days before going to London by train on 16 December. He stayed in London until 6 January 1913 and during his stay there he gave multiple talks. In one of his talks on 2 January he spoke about women's suffrage to the Women's Freedom League — part of his address, and the accompanying print coverage of his talk, noted the examples of Táhirih, Mary Magdalene, and Queen Zenobia to the organization.[165][166]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left London by the Euston Station at 10am and arrived in Edinburgh at 6.15pm where he was met by Jane Elizabeth Whyte, a notable Scottish Baháʼí and wife of Alexander Whyte, and others.[167][168] While in Edinburgh he and his associates stayed at the Georgian House of #7 Charlotte Square. On 7 January ʻAbdu'l-Bahá visited the Outlook Tower, and then went on a driving tour of some of Edinburgh and the nearby countryside;[169] later in the afternoon he met with students of the University of Edinburgh in the library of 7 Charlotte Sq, followed by a talk to the Edinburgh Esperanto Society in the Freemason's Hall. The meeting in the library was run by Alexander Whyte who said "Dear and honoured Sir, I have had many meetings in this house, but never have I seen such a meeting It reminds me of what St. Paul said, ' God hath made of one blood all nations of men,' and of what our Lord said, ' They shall come from the East and the West, from the North and the South, and shall sit down in the Kingdom of God.'"[170]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's stay in Edinburgh was covered by The Scotsman newspaper.[171][172][173][174] The newspaper coverage lead to a stream of visitors and speaking engagements on 8 Jan; he spoke at the Edinburgh College of Art, and the North Canongate School.[nb 7] Later in the evening he spoke at Rainy Hall, which is part of New College, which was followed by a viewing of Handel's Messiah in St Giles' Cathedral. Visitors again came on the 9th, and in the evening he gave a talk with the Theosophical society hosted by David Graham Pole. That night and or early the next morning ʻAbdu'l-Bahá wrote a letter to Andrew Carnegie.[178][179] The letter commented on reading The Gospel of Wealth.[180][181] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá again sent a letter to Carnegie in 1915.[182]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and his associates leave Edinburgh mid-morning on the 10th, and went back to London until the 15th. Then he was in Bristol on 15 and 16 January, coming back to London where he stayed until the 21st, except for a trip to Woking on the 18th.[1]

Continental Europe

[edit]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's arrived in Paris on 22 January; the visit which was his second to the city last for a couple months. During his stay in the city he continued his public talks, as well as with meeting Baháʼís, including locals, those from Germany, and those who had come from the East specifically to meet with him. During his stay in Paris, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's stayed at an apartment at 30 Rue St Didier which was rented for him by Hippolyte Dreyfus-Barney.[183]

Some of the notables that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá met while in Paris include the Persian minister in Paris, several prominent Ottomans from the previous regime, professor 'Inayatu'llah Khan, and E.G. Browne.[183] He also gave a talk on the evening of the 12th to the Esperantists, and on the next evening gave a talk to the Theosophists at the Hotel Moderne. He had met with a group of Pairs professors and theological students at Pasteur Henri Monneir's Theological Seminary; Pasteur Monnier was a distinguished Protestant theologian, vice-president of the Protestant Federation of France and professor of Protestant theology in Paris.[184] Around a week later, on the 21st, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá spoke at the Salle de Troyes which was organized by L'Alliance Spiritualiste.[183] On 30 March, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left Paris toward Stuttgart.

He visited Germany for 8 days in 1913, including visiting Stuttgart, Esslingen and Bad Mergentheim.[19] During this visit he spoke to a youth group as well as a gathering of Esperantists.[185] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left Stuttgart to go to Budapest, and on his way he changed trains in Vienna, where a number of Iranian Baháʼís were waiting for him.[186] He spoke to them while he was waiting for the train to Budapest. In Budapest ʻAbdu'l-Bahá met with a number of well known social leaders including academics and leaders of peace movements including Turks, Arabs, Jews and Catholics. See the Baháʼí Faith in Hungary. He also met with the Theosophical Society, and the Turkish Association. On 11 April he spoke at the hall of the old building of parliament, and on the next day he spoke to some visitors who included the president of the Turanian Society.[186] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was supposed to leave to Vienna on the 15th, but because of a cold he did not travel to Vienna until 18 April.[186][187] In Vienna ʻAbdu'l-Bahá met with the Persian minister, the Turkish Ambassador in multiple occasions, and spoke with Theosophists on three separate days. He also met with Bertha von Suttner, who was the first woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize.[186] He left Vienna on the 24th, and went back to Stuttgart where he arrived early on 25 April 1913. During his week in Stuttgart, he mostly stayed at his hotel due to a lingering cold, but he did give a talk at a museum, as well as receiving guests at his room.[188]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá left Stuttgart on 1 May, arriving in Paris on the 2nd for his third stay in the French capital; he stayed in Paris until 12 June.[188] Because his travels had led to reduced physical strength, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was largely unable to go to meetings held in Baháʼí homes during his final stay in Paris, but he did hold meetings and talks at his hotel. He also met again with Turkish and Persian ministers. On June 6h, Ahmed Izzet Pasha, the former grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire, gave a dinner party for ʻAbdu'l-Bahá.[188] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá gave his final farewell at the Paris train station, when he boarded a train for Marseilles on 12 June. He stayed in Marseilles for one night before boarding the P & O steamer Himalaya early the next morning on 13 June. The steamer landed in Port Said in Egypt on 17 June 1913.[188]

Return to Egypt

[edit]When ʻAbdu'l-Bahá returned to Egypt, he decided not to immediately go back to Haifa. He stayed in Port Said until 11 July, and during his time there he met with many Baháʼís, who had come to visit him from Haifa, and local Muslims and Christians.[188] Because of bad weather conditions, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá moved to Ismailia, but there he contracted a fever and only attended his mail during his week there. Thinking that the humid conditions in Alexandria would be better for his health, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá travelled on 17 July to a Ramleh, a suburb of Alexandria. On 1 August, his grandson Shoghi Effendi, his sister Bahíyyih Khánum and his eldest daughter came to visit him from Haifa.[188] Later during his stay he again met with ʻAbbas II of Egypt, the Khedive of Egypt. Finally on 2 December he boarded a Lloyd Triestino boat, and headed for Haifa with stops in Port Said and Jaffa. He landed in Haifa in the early afternoon of 5 December 1913.[188]

See also

[edit]- 1910 in rail transport, 1911 in rail transport, 1912 in rail transport, 1913 in rail transport

- Baháʼí timeline

- Baháʼí Faith in Egypt

- Baháʼí Faith in the United Kingdom

- Baháʼí Faith in Germany

- Baháʼí Faith in Hungary

References

[edit]- ^ Note several volumes covering the talks given on ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's journeys are of incomplete substantiation — "The Promulgation of Universal Peace", "Paris Talks" and "ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in London" contain transcripts of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's talks in North America, Paris and London respectively. While there exists original Persian transcripts of some, but not all, of the talks from "The Promulgation of Universal Peace", "Paris Talks", there are no original transcripts for the talks in "ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in London". See Research Department of the Baháʼí World Center (22 October 1996). "Authenticity of some Texts". Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2010..

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (2006). Paris Talks Addresses Given by Abdul-Baha in 1911. UK Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 978-1-931847-32-2.

- Blomfield, Lady (1975) [1956]. "Abdu'l–Baha in London" and "ʻAbdu'l–Baha in Paris". The Chosen Highway; Part III (ʻAbdu'l–Bahá). London: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 147–187. ISBN 978-0-87743-015-5. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014.

- Thompson, Juliet; Gail, Marzieh (1983). "With ʻAbdu'l–Bahá in Thonon, Vevey, and Geneva". The diary of Juliet Thompson. Kalimat Press. pp. 147–223. ISBN 978-0-933770-27-0. Archived from the original on 7 April 2013.

- ^ Transcripts of many talks given by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in the US and Canada can be found in:

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1982) [1922]. The Promulgation of Universal Peace (2nd ed.). US Baháʼí Publishing Trust. p. 513. ISBN 978-0-87743-172-5. Archived from the original on 8 October 2013.

- Brown, Ramona Allen (1980). Memories of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá; Recollections of the Early Days of the Baháʼí Faith in California. US: US Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 978-0-87743-139-8.

- Gail, Marzieh (1991). "Chapters: 15 to 18". Arches of the Years. George Ronald Publisher. ISBN 978-0-85398-325-5.

- Ives, Howard Colby (1983) [1937]. Portals to Freedom. UK: George Ronald. ISBN 978-0-85398-013-1.

- Mahmúd-i-Zarqání, Mírzá (1998) [1913]. Mahmúd's Diary Chronicling ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Journey to America. Oxford: George Ronald. ISBN 978-0-85398-418-4. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013.

- Parsons, Agnes (1996). Hollinger, Richard (ed.). ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in America; Agnes Parsons' Diary. US: Kalimat Press. ISBN 978-0-933770-91-1.

- Thompson, Juliet; Gail, Marzieh (1983). "ʻAbdu'l–Bahá in America". The diary of Juliet Thompson. Kalimat Press. pp. 223–. ISBN 978-0-933770-27-0. Archived from the original on 4 April 2013.

- Ward, Allan L. (1979). 239 Days; ʻAbdu'-Bahá's Journey in America. US Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 978-0-87743-129-9.

- Ward, Allan L. (1960). "An historical study of the North American speaking tour of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and a rhetorical analysis of his addresses". University Libraries ALICE Online Catalog. Ohio University Libraries (Athens). Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- "Hand of Cause Robarts present at Canadian Association's fifth annual conference". Baháʼí News. No. 515. October 1980. p. 12. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014.

- "Analysis of Topics Published in World Order". Baháʼí Bibliography. Baháʼí Library Online. September 2003. Archived from the original on 4 April 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ Note Sulzer would go on to write expansively of the Baha'i Faith as he understood it:

- Sulzer, William (14 February 1920). "What is Bahaism?". The Broad Ax. Salt Lake City, Utah. p. 2. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- "William Sulzer will speak…". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. 20 February 1932. p. 13. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- ^ The first film was by a production company that asked if they could film him for few minutes to appear in a newsreel the first week he arrived He agreed over the objection of the Baháʼís who felt the process was not socially proper. This first film was incorporated into a 1985 documentary by the BBC TV unit in 1985 called "The Quiet Revolution" as part of the "Everyman" TV series.

- ^ The hotel was located at Broadway and 7th.[153] The hotel was sold in 1919 and the company that owned it dissolved in 1933.[154]

- ^ Transcripts of many talks given by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in the US and Canada can be found in:

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1987) [1912]. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in London; Addresses & Notes of Conversations. UK Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 978-0-900125-89-8. Archived from the original on 8 October 2013.

- Sohrab, Ahmad. David Merrick (ed.). Abdu'l-Bahá in the UK 1913; the Diary of Ahmad Sohrab; 5 Dec 1912 – 21 Jan 1913 (Draft) (PDF). David Merrick. p. 250. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2018.

- Blomfield, Lady (1975) [1956]. "ʻAbdu'l–Baha in London" and "ʻAbdu'l–Baha in Paris". The Chosen Highway; Part III (ʻAbdu'l–Bahá). London: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 147–187. ISBN 978-0-87743-015-5. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014.

- Gollmer, Werner (1988). ʻAbdu'l-Baha in Germany. Baháʼí-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-87037-215-6.

- Khursheed, Anjam (1991). The Seven Candles of Unity; The Story of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in Edinburgh. London: Baha'i Publishing Trust of the UK. p. 246. ISBN 978-1-870989-12-1.

- Sohrab, Ahmad. David Merrick (ed.). Abdu'l-Bahá in Edinburgh; The Diary of Ahmad Sohrab; 6 Jan 1913 – 10 Jan 1913 (PDF). David Merrick. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2013.

- "Abdu'l-Bahá's Visit to Edinburgh 1913" (PDF). based on Sohrab's Diary and The Seven Candles of Unity. 22 June 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ The school was closed and renamed the "Canongate Venture",[175] scheduled for demolition in 2008,[176] but which survived at least to 2010.[177]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Smith 2000, pp. 16–18

- ^ a b Momen 2004, pp. 63–106

- ^ "Baha'i Faith History in Azerbaijan". National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Azerbaijan. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- ^ Balci, Bayram; Jafarov, Azer (21 February 2007), "The Baha'is of the Caucasus: From Russian Tolerance to Soviet Repression {2/3}", Caucaz.com, archived from the original on 11 September 2012

- ^ Hassall, Graham (1993). "Notes on the Babi and Baha'i Religions in Russia and its territories". Journal of Baháʼí Studies. 05 (3): 41–80, 86. doi:10.31581/JBS-5.3.3(1993). Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ^ Egea, Amin (2011). "The Travels of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and their Impact on the Press". Lights of Irfan. 12. Wilmette, IL: Haj Mehdi Armand Colloquium: 1–25. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ^ Smith, Peter (2004). Smith, Peter (ed.). Baha'is in the West. Vol. 14. Kalimat Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-890688-11-0.

- ^ Hands of the Cause living in the Holy Land (1964). The Baháʼí Faith: 1844-1963: Information Statistical and Comparative. Baháʼí World Center. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013.

- ^ Khan, Janet A. (2005). Prophet's Daughter The Life and Legacy of Bahíyyih Khánum, Outstanding Heroine Of The Baháʼí Faith. Wilmette, IL: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-1-931847-14-8.

- ^ a b c d Balyuzi 2001, pp. 133–68

- ^ Hartzler & Shoemaker 1912, pp. 247–249

- ^ Hassal, Graham (1997). "Baha'i country notes: Egypt". Archived from the original on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2006.

- ^ Hassall, Graham (1993). "Notes on the Babi and Baha'i Religions in Russia and its territories". Journal of Baháʼí Studies. 5 (3): 41–80, 86. doi:10.31581/JBS-5.3.3(1993). Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- ^ Hassall, Graham (c. 2000). "Egypt: Baha'i history". Asia Pacific Baháʼí Studies: Baháʼí Communities by country. Baháʼí Online Library. Archived from the original on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ^ "Allan Line Steamship Fleet List - 1907 - 27 Vessels (Bottom of Page)". GG Archives. GG Group. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ^ "S/S Corsican, Allan Line". Passenger lists and emigrant ships from Norway Heritage. www.norwayheritage.com. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Blomfield 1975, pp. 147–185

- ^ Yazdi, Ali M. (1987). Blessings Beyond Measure Recollections of Abdu'l-Baha and Shoghi Effendi. US Baháʾí Publishing Trust. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-87743-211-1.

- ^ a b c d Balyuzi 2001, pp. 159–397

- ^ various (20 August 1911). Windust, Albert R; Buikema, Gertrude (eds.). "various". Star of the West. 02 (9). Chicago, IL: Baháʼí News Service: all. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ^ ʻAbdu'l-Bahá; Wellesley Tudor Pole (1911). Spiller, G. (ed.). The Bahai Movement. Papers on Inter-racial Problems Communicated to the First Universal Races Congress. London: in London, P.S. King & Son and Boston, The World's Peace Foundation. pp. 154–157. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ a b "Hippolyte Dreyfus, apôtre d'ʻAbdu'l-Bahá; Premier Baháʼí français". Qui est Abdu'l-Baha ?. Assemblée Spirituelle Nationale des Baha'is de France. 9 July 2000. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ^ Kazemzadeh, Firuz (2009). "ʻAbdu'l-Bahá 'Abbás (1844–1921)". Baháʼí Encyclopedia Project. Evanston, IL: National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of the United States. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ^ Thompson & Gail 1983, pp. 147–223, "With ʻAbdu'l–Bahá in Thonon, Vevey, and Geneva"

- ^ Honnold 2010, pp. 51–52

- ^ "UK Baháʼí Heritage Site-A memorial to Lady Blomfield". Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. by Rob Weinberg and originally published in Baháʼí Journal UK

- ^ a b True, Corinne (27 September 1911). Windust, Albert R; Buikema, Gertrude (eds.). "Towards Spiritual Unity". Star of the West. 02 (10–11). Chicago, IL: Baháʼí News Service: 2, 4–7. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ^ Canney 1921, p. 102

- ^ a b c d e ʻAbdu'l-Bahá 1911

- ^ a b "Alice Mary Buckton". History, genealogical data and interesting facts about the Buckton family. Buckton Family. 2010. Archived from the original on 18 June 2010. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ^ trans. Hammond, Eric (June 1909). Cranmer-Byng, L.; Kapadia, SA (eds.). Wisdom of the East; The splendour of God; being extracts from the sacred writings of the Bahais. London: John Murray, Albamarle St. p. 124. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012.

- ^ "Minutes of the ... annual session of the Synod of New York". Presbyterian in the Synod of the Northeast. 29 March 1914. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ^ Rev. Simpson, Albert B; Rev. Smith, Eugene R., eds. (October 1881). "Persia Mission of the Presbytrian Church, Independent Mission Work In Persia and the Caucasus" (PDF). The Gospel in All Lands. 04 (4). New York: Bible House: 175–177. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ^ Mírzá Abu'l-Faḍl Gulpáygání (1998) [1912]. The Brilliant Proof. Los Angeles: Kalimát Press. p. APPENDIX Bahaism – A Warning, by Peter Z. Easton. Archived from the original on 6 April 2013.

- ^ Burhan-i-Lamiʻ (The Brilliant Proof): Published, along with an English translation, in Chicago in 1912, the paper responds to a Christian clergyman's questions. Republished as Mírzá Abu'l-Faḍl Gulpáygání (1998) [1912]. The Brilliant Proof. Los Angeles: Kalimát Press. Archived from the original on 8 April 2013.

- ^ Lambden, Stephen N. "Thomas Kelly Cheyne (1841-1915), Biblical Scholar and Baháʼí". Hurqalya Publications. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ^ "Persian Prophet of Bahaism a London Society Cult". The Pittsburg Gazette Times. 1 October 1911. pp. 2, Second section. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ^ "Bahaism. A New Religion from Persia "Prophet's" visit to London". Grey River Argus. New Zealand. 6 November 1911. p. 1. Archived from the original on 29 September 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ^ "Bahaism. A New Religion from Persia "Prophet's" visit to London". Poverty Bay Herald. New Zealand. 21 October 1911. p. 1. Archived from the original on 29 September 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ^ a b Moody, A. David (11 October 2007). Ezra Pound Poet I The Young Genius 1885-1920. Oxford University Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-19-921557-7. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ^ a b ʻAbdu'l-Bahá 1995, pp. 15–17

- ^ Beede, Alice R. (7 February 1912). Windust, Albert R; Buikema, Gertrude (eds.). "A Glimpse of Abdul-Baha in Paris". Star of the West. 02 (18). Chicago, IL: Baháʼí News Service: 6, 7, 12. Archived from the original on 7 April 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ^ a b ʻAbdu'l-Bahá 1995, pp. 119–123

- ^ "Memorial to a shining star". Baháʼí International News Service. Baháʼí International Community. 10 August 2003. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ^ Abdu'l-Bahá (1916). Lady Blomfield (ed.). Talks by Abdul Baha Given in Paris. G. Bell and Sons, LTD. p. 5.

- ^ Taqizadeh, Hasan; Muhammad ibn ʻAbdu'l-Vahhad-i Qazvini (1998) [1949]. "ʻAbdu'l-Baha Meeting with Two Prominent Iranians". Published academic articles and papers. Bahai Academic Library. Archived from the original on 4 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ^ Hatcher & Martin 2002

- ^ Ward 1979, p. ix, 10

- ^ Wilson 1915, pp. 263–286

- ^ Terry, Peter (1992, 2015) Rabindranath Tagore: Some Encounters with Baháʼís.

- ^ Kazemzadeh, Firuz (2009). "ʻAbdu'l-Bahá 'Abbás (1844–1921)". Baháʼí Encyclopedia Project. Evanston, IL: National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of the United States.

- ^ "News Clips". ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in America • 1912-2012. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of the United States. 2011. Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ Egea, Amin (2011). "The Travels of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and their Impact on the Press". Lights of Irfan. 12. Wilmette, IL: Haj Mehdi Armand Colloquium: 1–25. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ a b Mahmúd-i-Zarqání 1998, p. [page needed]

- ^ Mahmúd-i-Zarqání 1998, p. 17

- ^ Mahmúd-i-Zarqání 1998, p. 20

- ^ Mahmúd-i-Zarqání 1998, pp. 21–22

- ^ a b c d e f Lacroix-Hopson & ʻAbdu'l-Bahá 1987

- ^ Mahmúd-i-Zarqání 1998, pp. 22–23

- ^ Poirier, Brent (2002). "ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Immigration Record". Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ Mahmúd-i-Zarqání 1998, pp. 27–28

- ^ Mahmúd-i-Zarqání 1998, pp. 34–35

- ^ Thompson & Gail 1983, pp. 233–234, "ʻAbdu'l–Bahá in America"

- ^ "Persian Prophet Here; Abdul Baha ʻAbbas Comes to Preach Universal Peace". New York Tribune. 12 April 1912. p. 13, col. 3. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ "In Exile for 50 Years' Bahai Leader Comes to New York to Urge World Peace; He favors woman suffrage". Washington Post. 11 April 1912. p. 4, col. 4. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Mahmúd-i-Zarqání 1998, p. 37

- ^ ʻAbdu'l-Bahá 1912, p. [page needed]

- ^ a b c Thompson & Gail 1983, p. [page needed]

- ^ Ward 1979

- ^ Metelmann 1997, pp. 150–184

- ^ "ʻAbdu'l-Baha prays in Ascension Church" (PDF). New York Times. 15 April 1912. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ "Abdul Baha Preaches; Head of Bahai Movement Says All shall be Brothers Some Day". New York Tribune. 15 April 1912. p. 3, col. 3. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ^ "Bahai Leader in Pulpit; Abdul Baha Abbas Preaches to Fashionable Congregation; Message of World Peace Voiced by Persian Philosopher in Fifth Avenue Church". Washington Post. 15 April 1912. p. 4, col. 4. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Ward 1979, p. 23

- ^ Schmidt, Barbara. "KATE CAREW, "The Only Woman Caricaturist"". Special Features. Archived from the original on 21 January 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ^ a b Williams, Mary (5 May 1912). "Abdul Baha Talks to Kate Carew of Things Spiritual and Mundane" (PDF). New York Tribune. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ Ward 1979, pp. 27–35

- ^ "Free Money on Bowery; Abdul Baha Visits Mission and Distributes Quarters". New York Tribune. 20 April 1912. p. 16. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ Ives 1983, pp. 63–67

- ^ Balyuzi 2001, p. 232.

- ^ "A Message from Abdul Baha, Head of the Bahais" (PDF). New York Times. 21 April 1912. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ "Boston Letter; A Continuous issue of Books Planned by its Publishers; Bahaism" (PDF). New York Times. 28 April 1912. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ Parsons 1996, pp. 23–26

- ^ Musta, Lex (25 March 2009). "Get on the Bus for a Spiritual Journey through DC and Baha'i History". The News. Bahai Faith, Washington DC. Archived from the original on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ a b c Morrison 1982, pp. 50–62

- ^ Ward 1979, pp. 40–41

- ^ Parsons 1996, pp. 31–34

- ^ Thompson & Gail 1983, pp. 269–270, "ʻAbdu'l–Bahá in America"

- ^ Menon, Jonathan (27 April 2012). "At 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue". 239 Days in America - a Social Media Documentary. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- ^ ʻAbdu'l-Bahá 1912, pp. 49–52

- ^ Thomas 2006, pp. 32–33

- ^ "Bahai Leader May Address Bethel Literary". Washington Bee. 30 March 1912. p. 2, col. 4. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ "Persian Priest Attracts Society Women to the Cult of Bahaism; Followers kiss flowing robes of Abdul Baha at his Address to Leaders of Washington Smart Circles, in the ...". Washington Post. 26 April 1912. p. 12, col. 3 & 4. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ "Prayer for Abdul Baha; Methodists Hope he will "See LIght" and Go Home". Washington Post. 29 April 1912. p. 2, col. 6. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ "ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in Chicago". Baháʼí News. No. 558. September 1977. pp. 2–8. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014.

- ^ "Abdu'l-Baha and the House of Worship". National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of the United States. 17 April 2008. Archived from the original on 28 December 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ Perry, Mark (10 October 1995). "S. Abbott and the Chicago Defender: A Door to the Masses". Michigan Chronicle. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011 – via Bahá'í Association of The University of Georgia.

- ^ Ottley, Roi. The Lonely Warrior. United States of America: Henry Regnery Company, 1955. Print. 160.

- ^ Du Bois, W. E. Burghardt; MacLean, M. D., eds. (May 1912). "Men of the Month". The Crisis; A Record of the Darker Races. 4 (1). National Association for the Advancement of Colored People: 14–16. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ Morrison 1982, pp. 55, 150

- ^ Du Bois, W. E. Burghardt; MacLean, M. D., eds. (June 1912). "The Fourth Annual Conference of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People". The Crisis; A Record of the Darker Races. 4 (2). National Association for the Advancement of Colored People: 80. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- ^ ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (June 1912). Du Bois, W. E. Burghardt; MacLean, M. D. (eds.). "The Brotherbood of Man". The Crisis; A Record of the Darker Races. 4 (2). National Association for the Advancement of Colored People: 88–89. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- ^ Sims 1989, pp. 1–2

- ^ Mahmúd-i-Zarqání 1998, pp. 81–83

- ^ Busta-Peck, Christopher (16 April 2009). "ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and the Baháʼí Faith". Cleveland in Cuyahoga County, Ohio. HMdb.org. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Etter-Lewis 2006, pp. 51–52

- ^ Buck, Christopher (24 September 2007). Alain Locke; "Race Amity" & the Baháʼí Faith. Alain Lock Centenary Program. Washington D.C.: American Association of Rhodes Scholars, Howard University. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Leader of Bahaism is Coming to Pittsburgh". The Gazette Times. 4 July 1912. p. 7. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ a b Francis, Richard (1998). "Martha Root - Herald of the Kingdom, Lioness at the Threshold". Biographies. Baha'i Library Online. Archived from the original on 4 April 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ Mahmúd-i-Zarqání 1998, pp. 100–103

- ^ Ives 1983, p. 196

- ^ Parsons 1996, p. 161

- ^ "Head of New Religion of Peace". Atlanta Constitution. American Press Association. 30 May 1912. p. 7. ProQuest 496578595.

- ^ a b Report of the annual Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration. Lake Mohonk: Harvard University. 1912. pp. 42–44.

- ^ "Head of New religion Prominent at Lake Mohonk Conference". The Lowerll Sun. 18 May 1912. p. 6. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Elkinton, Joseph (30 May 1912). "The Mohonk Conference on Peace and International Arbitration of 1912". The Friend; A Religious and Literary Journal. 85 (48). Edwin P. Sellew: 379. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ Free Religious Association (Boston, Mass.) Meeting (1912). Proceedings at the 45th Annual meeting of the Free Religious Association. Adams & Co. pp. 84–90.

- ^ Spring 1944, p. 161

- ^ Bixby, James T. (1912). "What is Behaism?". The North American Review. 195 (679): 833–846. JSTOR 25119778.

- ^ Foster, E (28 April 1910). Windust, Albert R; Buikema, Gertrude (eds.). "Address at Metropolitan Temple Reception, 7th Ave and 14th St, NY, May 28, 1912". Star of the West. 03 (7). Chicago, IL: Baháʼí News Service: 14–15. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ "Points toward Peace; Religious Unity will bring World Amity, says Persian Teacher" (PDF). New York Times. 29 May 1912. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ Hubbard 1912, pp. 21–40

- ^ Venters, III, Louis E. (2010). Most great reconstruction: The Baha'i Faith in Jim Crow South Carolina, 1898-1965 (Thesis). Colleges of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina. pp. 127–129. ISBN 978-1-243-74175-2. Archived from the original on 6 April 2014.

- ^ Muriel Ives Barrow Newhall (1998). "Stories of Muriel Ives Newhall Barrow: Grace Robarts Ober". Archived from the original on 4 April 2013.

- ^ a b Mahmúd-i-Zarqání 1998, p. 42

- ^ "Sixtieth Anniversary of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Travels to the Western World". Baháʼí News. No. 488. November 1971. p. 7. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014.

- ^ "New York Sites Visited by ʻAbdu'l·Baha". Baháʼí News. No. 423. June 1966. p. 8. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014.

- ^ "Jersey's New Resident; Abdul Pasha, Persian Religious Leadder, to Live in Montclair". The New Brunswick Times. 3 June 1912. p. 7. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ ʻAbdu'l-Bahá 1912, pp. 213–215

- ^ Thompson & Gail 1983, pp. 322–325, "ʻAbdu'l–Bahá in America"

- ^ Mahmúd-i-Zarqání 1998, pp. 149–151

- ^ Johnston 1975, p. 10,317

- ^ Garis 1983, p. 53

- ^ Metelmann 1997, pp. 159–161

- ^ Parsons 1996, p. 69

- ^ Parsons 1996, pp. 113–120

- ^ Mahmúd-i-Zarqání 1998, pp. 209–220

- ^ Van den Hoonaard 1996, p. 49

- ^ "Apostle of Peace meets Socialists". The Montreal Gazette. 4 September 1912. p. 2. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ ‘Abdu’l-Bahá (1982). "5 September 1912 Talk at St. James Methodist Church – Montreal, Canada". The Promulgation of Universal Peace (2nd ed.). US Bahá’í Publishing Trust. p. 470. Archived from the original on 28 November 2012 – via Bahá’í Reference Library.

- ^ a b Van den Hoonaard 1996, pp. 56–68

- ^ a b Balyuzi 2001, p. 256

- ^ "Persian Peace Prophet gives Message to Canada through the Standard". The Harbor Grace Standard. 7 September 1912. p. 17. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ "Message of the Great Persian Reformer". Winnipeg Free Press. Winnipeg, Manitoba. 19 September 1912. p. 9, col. 3. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ Van den Hoonaard 1996, pp. 43–63

- ^ A portion of Van den Hoonaard's book is posted online along with rare pictures at "The Baháʼí Faith comes to Hamilton". The Baha'i Community of Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ MacEoin, Denis; Collins, William. "Memorials (Listings)". The Babi and Baha'i Religions: An Annotated Bibliography. Greenwood Press's ongoing series of Bibliographies and Indexes in Religious Studies. Archived from the original on 7 April 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Come to Lecture on Bahai Religion". Salt Lake Tribune. Salt Lake City. 30 September 1912. pp. 5, col. 4. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ "Come to Lecture on Bahai Religion". The Evening Standard. Ogden, Utah. 30 September 1912. pp. 14, col. 4. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ Allen, Frances Orr (16 October 1912). "ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in San Francisco, California". Star of the West. 3 (12): 9.

- ^ Brown 1980, p. 34

- ^ "Foreign Tongue Soothes; Bahaistic Leader Gives Advice and Comfort through Interpreter' Followers Quekk Threatened Revolt". Los Angeles Times. 21 October 1912. p. 110. ProQuest 159830527.

- ^ More information about the hotel can be found at Dickerson, Brent C. "A Visit to Old Los Angeles". Indexes of Grab-Bag Essays and Old Los Angeles Episodes. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Thompson, Daniella. "The Shattuck Hotel: Berkeley's Once and Future Jewel?". East Bay: Then and Now. Berkeley Landmarks. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Dobbs, Randolph (8 January 2010). "Los Angeles Baha'i community turns 100". Commemorations. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha'is of the United States. Archived from the original on 28 December 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ Stockman, Robert H. (2009). "Chase, Thornton (1847-1912)". Baháʼí Encyclopedia Project. Evanston, IL: National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of the United States. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Appeals to Jewish Hearers; Abdul Baha Addresses Washington Hebrew Congregation". The Washington Post. 9 November 1912. p. 3. ProQuest 145176477.

- ^ "Abdul Baha Within Week; Persian Philosopher will Speak in this City". The Baltimore Sun. 15 April 1912. p. 8. ProQuest 535264267.

- ^ "Women Kis His Hand; Persian Advoate of Human Brother is Venerated". The Baltimore Sun. 12 November 1912. p. 9. ProQuest 535257618.

- ^ "Abdul Baha here Tomorrow; Persian Philosopher Expected at Unitarian Church". The Baltimore Sun. 10 November 1912. p. 12. ProQuest 535221531.

- ^ "Minervas hear A Baha; Persian Sage Compliments 'Em on their "Radiant Faces"". New-York Tribune. 26 November 1912. p. 11. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ^ Effendi 1979, p. 281

- ^ Ives 1983, pp. 211–227

- ^ Balyuzi 2001, p. 343

- ^ "The Equality of Woman. Abdul Baha to Lecture to a W.F.L. Meeting". The Vote. 3 January 1913. p. 7. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ "(two stories) Towards Unity & An Eastern Prophet's Message: Abdul Baha says: "There is no distinction: Men and Women are Equal". The Vote. 10 January 1913. pp. 180–182. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ "Printable One-Page Timeline" (PDF). Abdu'l-Bahá's Visit to Edinburgh 1913. Edinburgh Baha'i Community. 22 June 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ "Take the Visual Tour". Abdu'l-Bahá's Visit to Edinburgh 1913. Edinburgh Baha'i Community. 22 June 2007. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ "Take the Visual Tour". ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Visit to Edinburgh 1913. Edinburgh Baha'i Community. 22 June 2007. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ Barbour 1923, p. 554

- ^ "International Amity, Meetings of Edinburg Citizens to Greet...". The Scotsman. 4 January 1913. p. 1. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ "Abdul Baha in Edinburgh". The Scotsman. 8 January 1913. p. 10. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ "Abdul Baha in Edinburgh". The Scotsman. 9 January 1913. p. 11. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ ""Bahaism" and Christianity". The Scotsman. 13 January 1913. p. 10. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ "The Canongate Venture". Canongate Community Forum. 13 August 1987. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ "Report on the Canongate Project, May – June 2008" (PDF). Canongate Community Forum. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ "A New Canongate Venture". Edinburgh Old Town Development Trust. 2010. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Effendi, Shoghi (1981). "Letter of 29 April 1948". Unfolding Destiny. US Bahá’í Publishing Trust. pp. 212–216. Retrieved 9 September 2020 – via Bahá’í Reference Library.

- ^ "Abdu'l-Bahá's Visit to Edinburgh 1913" (PDF). 22 June 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ Carnegie, Andrew. "The Gospel of Wealth and other Timely Essays". Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ "Abdul Baha's Tribute to Mr. Carnegie; Famous Persian Prophet Praises the "Gospel of Wealth" and Tells When the Rich May Give to the Poor". New York Times. 9 February 1913. pp. SM12, Magazine Section 6. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ "Carnegie Exalted by Bahaist Leader; Abdul Baha Abbas Sends Letter from Syria Extolling His Efforts for Peace" (PDF). New York Times. 5 September 1915. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ a b c Balyuzi 2001, pp. 373–379

- ^ Fazel, Seena (1993). "ʻAbdu'l-Bahá on Christ and Christianity". Baháʼí Studies Review. 03 (1). Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ Effendi 1979, pp. 286–87

- ^ a b c d Balyuzi 2001, pp. 383–387

- ^ "A Draft Summary of the History and International Character of the Hungarian Baháʼí Community". National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha'is of Hungary. 2011. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g Balyuzi 2001, pp. 388–401

References and further reading

[edit]- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1911). ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in London. London: Baháʼí Publishing Trust: 1982. ISBN 978-0-900125-50-8. Archived from the original on 6 October 2013.

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1912). The Promulgation of Universal Peace (Hardcover ed.). Wilmette, IL: Baháʼí Publishing Trust: 1982. ISBN 978-0-87743-172-5. Archived from the original on 8 October 2013.

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1995) [1912]. Paris Talks (Hardcover ed.). Baháʼí Distribution Service. ISBN 978-1-870989-57-2. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012.

- Balyuzi, H.M. (2001). ʻAbdu'l-Bahá The Centre of the Covenant of Baháʼu'lláh (Paperback ed.). Oxford: George Ronald. ISBN 978-0-85398-043-8.

- Barbour, G. F. (1923). The Life of Alexander Whyte. London: Hodder and Stoughton, Ltd. Archived from the original on 3 April 2014.

- Blomfield, Lady (1975) [1956]. The Chosen Highway. London: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 978-0-87743-015-5. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009.

- Brown, Ramona Allen (1980). Memories of ʹAbduʹl-Bahá recollections of the early days of the Baháʹí faith in California. US Baháʹí Publishing Trust. ISBN 978-0-87743-128-2.

- Canney, Maurice Arthur (1921). An encyclopaedia of religions. G. Routledge & sons, ltd. p. 102.

- Effendi, Shoghi (1979) [1940]. God Passes By. US Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 288–290. ISBN 978-0-87743-020-9. Archived from the original on 27 November 2013.

- Etter-Lewis, Gwendolyn (2006). "Radiant Lights: African-American Women and the Advancement of the Baháʼí Faith in the U.S.". In Etter-Lewis, Gwendolyn; Thomas, Richard Walter (eds.). Lights of the spirit historical portraits of Black Baháʼís in North America, 1898-2004. US Baha'i Publishing Trust. pp. 49–67. ISBN 978-1-931847-26-1.

- Garis, M.R. (1983). Martha Root Lioness at the Threshold. Wilmette, IL: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 978-0-87743-185-5.

- Hartzler, Jonas Smucker; Shoemaker, J. S. (1912). Among missions in the Orient and observations. Scottdale, Pa.: Mennonite publishing house.

- Hatcher, William S.; Martin, J. Douglas (2002). The Baha'i Faith: The Emerging Global Religion. US Baha'i Publishing Trust. ISBN 978-1-931847-06-3.

- Honnold, Annamarie (2010). Vignettes from the Life of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. UK: George Ronald. ISBN 978-0-85398-129-9. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012.

- Hubbard, Elbert (1912). Hollyhocks and goldenglow. The Roycrofters. p. 21.

- Ives, Howard Colby (1983) [1937]. Portals to Freedom. UK: George Ronald. pp. 63–67. ISBN 978-0-85398-013-1. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012.

- Johnston, Ronald L. (1975). Religion and Society in Interaction: The Sociology of Religion. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. pp. 10, 317.

- Lacroix-Hopson, Eliane; ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1987). ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in New York- The City of the Covenant. NewVistaDesign. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013.

- Mahmúd-i-Zarqání, Mírzá (1998) [1913]. Mahmúd's Diary Chronicling ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Journey to America. Oxford: George Ronald. ISBN 978-0-85398-418-4. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013.

- Metelmann, Velda Piff (1997). Lua Getsinger; Herald of the Covenant. George Ronald. pp. 150–184. ISBN 978-0-85398-416-0. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012.

- Morrison, Gayle (1982). To move the world Louis G. Gregory and the advancement of racial unity in America. Wilmette, Ill: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 50–62. ISBN 978-0-87743-188-6.

- Momen, Moojan (2004). "Esslemont's Survey of the Baha'i World 1919–1920". In Smith, Peter (ed.). Baháʼís in the West. Kalimat Press. ISBN 978-1-890688-11-0.

- Negar Mottahedeh, ed. (3 April 2013). ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Journey West: The Course of Human Solidarity. Palgrave Macmillan US. ISBN 978-1-137-03201-0.

- Parsons, Agnes (1996). Hollinger, Richard (ed.). ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in America; Agnes Parsons' Diary. US: Kalimat Press. ISBN 978-0-933770-91-1.

- Sims, Barbara R. (1989). Traces That Remain: A Pictorial History of the Early Days of the Baháʼí Faith Among the Japanese. Osaka, Japan: Japan Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- Smith, Peter (2000). "ʻAbdu'l-Bahá" (PDF). A concise encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. pp. 14–20. ISBN 978-1-85168-184-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2012. (pp. 16–17)

- Spring, Agnes Wright (1944). William Chapin Deming of Wyoming pioneer publisher, and state and federal official. Arthur H. Clark Company.

- Thomas, Richard Walter (2006). "The "Pupil of the Eye": African-Americans and the Making of the American Baháʼí Community". In Etter-Lewis, Gwendolyn; Thomas, Richard Walter (eds.). Lights of the spirit historical portraits of Black Baháʼís in North America, 1898-2004. US Baha'i Publishing Trust. pp. 19–48. ISBN 978-1-931847-26-1.

- Thompson, Juliet; Gail, Marzieh (1983). The diary of Juliet Thompson. Kalimat Press. ISBN 978-0-933770-27-0. Archived from the original on 3 April 2014.

- Van den Hoonaard, Willy Carl (1996). The origins of the Baháʼí community of Canada, 1898-1948. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-88920-272-6.

- Ward, Allan L. (1979). 239 Days; ʻAbdu'-Bahá's Journey in America. US: US Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 978-0-87743-129-9.

- Wilson, Samuel Graham (1915). "Bahaism in America". Bahaism and Its Claims- A Study of the Religion Promulgated by Baha Ullah and Abdul Baha. Fleming H. Revell Co. ISBN 978-1-4097-8530-9.

- Natalie Jean Marine-Street, Abbas Milani, Shane Tedjarati, Negar Mottahedeh, Robert Stockman, Kioumars Ghereghlou, Mina Yazdani, Dominic Parviz Brookshaw, Richard Walter Thomas (13 July 2023). Abdu'l Baha at Stanford: A Centennial Conference (YouTube.com). San Francisco, CA: Stanford Iranian Studies Program.

External links

[edit]- Commemorating ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in America - 1912-2012 Centenary

- The Journey West: ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Travels - Europe & North America (1911-1913)

- Bushrui, Suheil Badi (2011). ʻAbbas Effendi and Egypt (in Arabic). Al-Kamel Verlag. ISBN 978-3-89930-381-0.

- BWNS: 100 years ago, historic journeys transformed a fledgling faith (30 August 2010).

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (August 2011). The Talks of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in France and Switzerland. Collected/translated by Jan T. Jasion. Paris, FR: Librairie Baháʼíe. ISBN 978-2-912155-25-2. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013.