Z-4 Plan

The Z-4 Plan was a proposed basis for negotiations to end the Croatian War of Independence with a political settlement. It was drafted by Peter W. Galbraith, Leonid Kerestedjiants and Geert-Hinrich Ahrens on behalf of a mini-Contact Group comprising United Nations envoys and diplomats from the United States, Russia and the European Union. The co-chairs of the International Conference on the Former Yugoslavia, David Owen and Thorvald Stoltenberg, were closely involved in the political process surrounding the plan. The document was prepared in the final months of 1994 and early 1995 before being presented to Croatian President Franjo Tuđman and the leaders of the self-declared Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK) on 30 January 1995. Tuđman was displeased with the proposal, but accepted it as a basis for further negotiations. However, the RSK authorities even refused to receive the document before UNPROFOR mandate status was resolved. According to later reactions, RSK leadership was not satisfied with the plan.

Three more attempts to revive the plan were made after Operation Flash in early May, when Croatia captured a portion of western Slavonia previously controlled by the RSK. The first initiative, that began later that month, failed because the RSK demanded that the Croatian forces pull back from western Slavonia (which Croatia declined to do). The second attempt failed simply because neither party wanted to negotiate. The final round of negotiations where the Z-4 Plan was proposed by international diplomats occurred in early August, when a major Croatian attack against the RSK seemed imminent. This time RSK leadership seemed more willing to negotiate based on Z-4 plan, but Croatia presented its own demands (including immediate replacement of the RSK with a Croatian civilian government), which were refused. On 4 August, Croatia launched Operation Storm, defeated the RSK and effectively ended the political process which led to the creation of the Z-4 Plan.

Elements of the plan made their way into two proposals on resolving the Kosovo crisis: in 1999 (during the Kosovo War) and in 2005 as a part of the Kosovo status process. Neither was accepted by the parties to that conflict.

Background

[edit]In August 1990 an insurgency known as the Log Revolution took place in Croatia, centred on the predominantly Serb-populated areas of the Dalmatian hinterland around the city of Knin,[1] parts of the Lika, Kordun, and Banovina regions, and settlements in eastern Croatia with significant Serb populations.[2] These areas were subsequently named the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK) and, after the RSK declared its intention to unite with Serbia, the Government of Croatia declared the RSK a breakaway state.[3] By March 1991 the conflict escalated, resulting in the Croatian War of Independence.[4] In June 1991, Croatia declared its independence as Yugoslavia disintegrated.[5] A three-month moratorium on Croatia and the RSK's declarations followed,[6] after which their decisions were implemented on 8 October.[7]

Since the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) increasingly supported the RSK and the Croatian Police were unable to cope with the situation, the Croatian National Guard (ZNG) was formed in May 1991. The ZNG was renamed the Croatian Army (HV) in November.[8] The establishment of the Croatian military was hampered by a September UN arms embargo.[9] The final months of 1991 saw JNA advances and the fiercest fighting of the war, culminating in the Siege of Dubrovnik[10] and the Battle of Vukovar.[11] In November a ceasefire was negotiated pending a political settlement (which became known as the Vance plan),[12] and it was implemented in early January 1992.[13] The ceasefire collapsed in January 1993 when the HV launched Operation Maslenica, and small-scale clashes continued for more than a year. On 16 March 1994, Russian envoy Vitaly Churkin brokered negotiations between Croatia and the RSK which produced a new ceasefire on 30 March. Further negotiations produced agreements on reopening a section of the Zagreb–Belgrade motorway (crossing the RSK-held part of western Slavonia, the Adria oil pipeline and several water-supply lines) by the end of 1994.[14]

Development

[edit]Creation

[edit]The Z-4 Plan was drafted by United States ambassador to Croatia Peter W. Galbraith, Russian ambassador to Croatia Leonid Kerestedjiants and German diplomat Geert-Hinrich Ahrens, representing the European Union (EU) in a "mini-Contact Group".[15] The Z in the plan's name stood for Zagreb (Croatia's capital), and 4 represented the involvement of the United States, Russia, the EU and the UN. The plan was the product of a process begun on 23 March 1994,[16] with Galbraith considering himself its principal author.[17] It was a well-developed legal document[18] intended as the basis for negotiations and, according to Ahrens, designed to commit Croatia to an internationally agreed settlement and prevent it from turning to a military resolution of the war[19] (while being generous to the Croatian Serbs). According to Ahrens, the plan was actually too generous to the Serbs;[18] in essence, it created the legal foundation for a permanent Serb state in Croatia.[20]

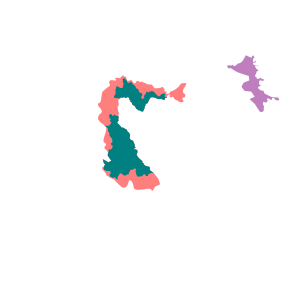

The heart of the plan was the Constitutional Agreement on Krajina (Part One). Part One defined Krajina as an autonomous region of Croatia, with borders based on the results of the 1991 Croatian census[19] (which identified eleven municipalities with an absolute Serb majority).[21] Those areas would enjoy a high level of autonomy, with most authority transferred from the central government in Zagreb to Krajina. The region would have its own president, cabinet, legislation, courts, police force, emblem, flag and currency, and the right to levy taxes and make international agreements.[19] Part One also provided for demilitarising the autonomous area. Part Two of the plan, the Agreements Concerning Slavonia, Southern Baranja, Western Sirmium and Other Areas, related to areas where the Croatian Serbs did not form the majority in 1991 (including eastern and western Slavonia) and contained transitional provisions. Part Three of the plan spelled out safeguards on human rights, fundamental freedoms, prosecution of war crimes, a human-rights court with international judges, and provisions allowing dual Croatian and Yugoslav citizenship for Croatian Serbs.[18] The plan envisaged that western Slavonia would be the first to be restored to Croatian control, followed by eastern Slavonia (where a transitional UN administration would be set up before the handover).[17]

Proposed changes

[edit]The first draft of the Z-4 Plan was prepared in September 1994, and further developed and amended on several occasions during the following four months. Over this period, International Conference on the Former Yugoslavia (ICFY) co-chairs David Owen and Thorvald Stoltenberg requested amendments to the plan and opposed its presentation to Croatian or RSK authorities. The first set of changes requested was to include a provision that Croatia cede territory around the city of Županja (on the north bank of the Sava River) to the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, allowing better communication between Belgrade and the Bosnian Serb territory around Banja Luka. The request, submitted on 8 September, was turned down by the plan authors.[22] That day, Owen requested that the plan allow Krajina to form a confederation with either Serbia or FR Yugoslavia. Owen and Stoltenberg sought to create a network of confederations between the former Yugoslav republics, but the authors of the Z-4 Plan deemed that impossible. German foreign minister Klaus Kinkel, on behalf of the German EU presidency, cautioned Owen that Krajina Serbs formed only 5 percent of Croatia's population and a confederation between Kosovo and Albania would be more natural. On 6 October Russia declared its opposition to the confederation, but Owen regained the country's support for the idea four days later (shortly before it was abandoned).[23]

The third group of requested amendments pertained to eastern Slavonia. Owen and Stoltenberg requested its status to be left unresolved, instead of gradually reverting to Croatian control over a five-year period and applying the postwar ethnic composition of the area as a formula for the ethnic mix of the local police and establishing a joint Croatian-Yugoslav company to extract crude oil in Đeletovci. The proposal was turned down, but it led to local autonomy for Serb villages in the area and reduced the transitional period to two years.[24] The fourth group of proposed amendments, tabled by Owen, included a proposal for continued Serb armed presence in Krajina and additional authority for Krajina concerning mineral resources and international treaties. After the proposals, the text of the plan became the subject of lengthy discussions between the contact group countries, the EU and the ICFY co-chairs. The co-chairs began drafting their version of the plan; Stoltenberg stalled the plan through Norwegian diplomat (and ICFY ambassador) Kai Eide,[25][26] creating a conflict between Eide and Galbraith.[27]

First news of the plan

[edit]On 1 October, Galbraith informed Croatian President Franjo Tuđman of the plan without providing any details. Similarly, Ahrens and Eide informed RSK president Milan Martić.[19] Although early Z-4 Plan negotiations were planned without actually disclosing the plan to Croatia and the RSK,[25] elements of the plan were leaked to Belgrade and Zagreb newspapers in mid-October.[27] According to Florence Hartmann, in October representatives of Tuđman and those of Serbian president Slobodan Milošević met in Graz, Austria to discuss the proposed reintegration of the RSK into Croatia and their opposition to the Z-4 Plan.[28] Tuđman disliked the plan because it envisaged a Serb state in Croatia, while Milošević saw it as a dangerous precedent that could be applied to majority non-Serb or ethnically mixed regions of rump Yugoslavia, such as Kosovo, Vojvodina and the Sandžak.[29][30]

Galbraith, Eide and Kerestedjiants agreed to deliver the plan to Croatia and the RSK on 21 October, opposed by Owen and Stoltenberg. Owen also asked Vitaly Churkin to instruct his envoy to oppose the delivery. As instructed by Moscow, Kerestedjiants pulled out of the move and Galbraith accused Owen of sabotaging the Z-4 Plan.[31]

Final version

[edit]The 53-page final version of the Z-4 Plan[32] was prepared on 18 January 1995. Entitled "Draft Agreement on the Krajina, Slavonia, Southern Baranja and Western Sirmium", it consisted of three documents and two provisional maps. The maps were considered provisional because of concerns that the inclusion of Benkovac in Krajina would be contested by Croatia; a portion of the municipality had been predominantly inhabited by Croats, and it was on the Adriatic coast. Another territorial issue was the municipality of Slunj; it was not included in Krajina, and the omission effectively cut Krajina in two. A possible solution to the problem was to split the municipality in two and award the areas east of Slunj to Krajina. In anticipation of this, planning began for a road bypassing Slunj. Despite the unresolved issues, delivery of the plan to Croatia and the RSK was scheduled for January.[33] On 12 January, shortly before the plan's final version was drafted, Tuđman announced in a letter to the UN that Croatia would not grant an extension of the UN peacekeeping mandate beyond 31 March and United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) troops deployed to the RSK would have to leave.[34]

Presentation

[edit]On 30 January the Z-4 Plan was presented to Tuđman by the French ambassador to Croatia, accompanied by Galbraith, Kerestedjiants, Ahrens and Italian ambassador Alfredo Matacotta (replacing Eide).[15] Tuđman did not hide his displeasure with the plan,[29] receiving the draft with the knowledge that Milošević's opposition to the plan (because of his concerns for Kosovo) would not allow it to be implemented.[35] Tuđman accepted the plan (which Croatia considered unacceptable) as a base for negotiations with the RSK,[32] hoping that they would dismiss it.[15]

The five diplomats then travelled to Knin to present the Z-4 Plan to the RSK leadership. There they met with Martić, RSK prime minister Borislav Mikelić and foreign minister Milan Babić. Martić refused to receive the draft before the UN Security Council issued a written statement extending the UNPROFOR mandate to protect the RSK. Kerestedjiants and Ahrens suggested that Martić should acknowledge receipt of the plan and then say that the RSK would not negotiate before the UNPROFOR issue was resolved, but he refused. The diplomats then attempted to meet Milošević in Belgrade about the matter, but Milošević refused to see them and the group returned to Zagreb the next day.[15] Ahrens described the events of 30 January as "a fiasco".[36]

Reactions

[edit]Ahrens noted that Croatia and the RSK were satisfied with the outcome. Owen and Stoltenberg expressed their understanding of the RSK's and Milošević's rejection of the plan, provoking a sharp reaction from Galbraith.[36] The RSK parliament convened on 8 February with the Z-4 Plan as the sole item on the agenda. In their speeches there, Martić, Mikelić and Babić described the plan as provocative to the RSK and saw Milošević's support in refusing the plan as greatly encouraging.[37] A number of other influential Serbian politicians rejected the plan in addition to Milošević, including Borisav Jović—a close ally of Milošević, who considered the RSK strong enough militarily to resist Croatia—and Vojislav Šešelj, who considered the plan totally unacceptable. The opposition politicians in Serbia were split. Zoran Đinđić said that since the RSK refused the plan Serbia should not accept it either, while Vuk Drašković favoured the plan as an historic opportunity.[38] Drašković's views ultimately prevailed in the Serbian media, but not before late August.[39] The only official reaction from Croatia was from its chief negotiator, Hrvoje Šarinić. Šarinić said that Croatia endorsed the restoration of Croatian rule, the return of refugees and local self-government for Croatian Serbs, but dismissed plan solutions incompatible with the Constitution of Croatia.[32] In Croatia, the plan and its authors (especially Galbraith) were strongly criticised in what Ahrens described as a "vicious campaign".[36]

Attempts of reintroduction

[edit]May and June 1995

[edit]There were several more attempts to advocate the Z-4 Plan as the basis of a political settlement of the Croatian War of Independence. After Croatia captured western Slavonia from the RSK in Operation Flash in early May, Owen and Stoltenberg invited Croatian and RSK officials to Geneva in an effort to revive the plan. The initiative was endorsed by the UN Security Council and the G7, which was preparing its summit in Halifax at the time. The meeting was attended by Owen, Stoltenberg, Galbraith, Kerestedjiants, Eide and Ahrens as the international diplomats; the RSK was represented by Martić, Mikelić and Babić, and the Croatian delegation was led by Šarinić. Šarinić accepted the invitation, claiming that the venue was a Croatian concession because Croatian authorities considered the issue an internal matter which should normally be dealt with in Croatia. On the other hand, the RSK delegation insisted on Croatian withdrawal from the territory captured earlier that month before negotiations could proceed. Since no such withdrawal was requested by the UN Security Council, Croatia rejected the demand and the initiative collapsed.[40]

A second attempt to revive the plan arose from talks between Kinkel and French foreign minister Hervé de Charette on 28 June. They proposed establishing zones of separation to enforce a ceasefire, monitoring the RSK's external borders, specific guarantees for the safety of Croatian Serbs and implementing confidence-building measures by economic cooperation between Croatia and the RSK. The initiative, however, did not gain ground when the RSK refused to negotiate.[41]

August 1995

[edit]Another effort involving the plan came about after Milošević asked the United States to stop an imminent Croatian attack against the RSK on 30 July. Although in his request he indicated that negotiations should be held based on the Z-4 Plan, he refused to meet Galbraith (who wanted Milošević to pressure the RSK into accepting it) on 2 August.[42] Instead, Galbraith met Babić in Belgrade in an effort to persuade him to accept the plan. He told Babić that the RSK could not expect international sympathy because of its involvement in the Siege of Bihać, and they would have to accept Croatian terms to avoid war. As an alternative, Galbraith advised Babić to accept negotiations based on the Z-4 Plan.[43] Babić complied, and Stoltenberg invited Croatian and RSK delegations to talks on 3 August.[41] Genthod, near Geneva,[44] was selected as the location to avoid media attention.[45] The RSK delegation was headed by Major General Mile Novaković of the Army of the Republic of Serb Krajina and the Croatian delegation was headed by Tuđman's advisor, Ivić Pašalić.[46]

At the meeting the RSK insisted on the withdrawal of the HV from western Slavonia and the gradual implementation of a ceasefire, followed by economic cooperation before a political settlement was discussed. The Croatian delegation did not intend to negotiate, but to prepare diplomatically for a military resolution of the war. Stoltenberg proposed a seven-point compromise, including negotiations based on the Z-4 Plan, beginning on 10 August.[46] The proposal was initially accepted by Babić, who then expressed reservations about the Z-4 Plan as a political settlement when he was asked to publicly declare support for the Stoltenberg proposal (so the Novaković delegation would follow his lead). Pašalić then asked Novaković to accept Croatia's seven demands,[47] including immediate replacement of the RSK with a Croatian civilian government.[46] Novaković refused Pašalić's proposal, indicating that he accepted the Stoltenberg proposal instead, and Pašalić declared that the RSK had declined a Croatian offer to negotiate.[47] Croatia did not consider Babić powerful enough to secure support for an initiative from Martić, and thus unable to commit the RSK to an agreement.[48] This view was supported by Babić himself, who told Galbraith during their 2 August meeting in Belgrade that Martić would only obey Milošević.[49] On 4 August Croatia launched Operation Storm against the RSK and, according to Galbraith, effectively terminated the Z-4 Plan and its associated political process.[16]

One final attempt, organised by Babić, was made to revive the Z-4 Plan on 16 August. This initiative called for negotiating each point of the plan and extending the autonomous areas to eastern Slavonia. However, Ahrens and Stoltenberg considered any talks between Croatia and the exiled, discredited leaders of the RSK impossible. When they consulted Šarinić about the initiative, he dismissed any possibility of negotiation.[50]

September 1995 and beyond

[edit]Following Croatian military success against the RSK during Operation Storm in August, and in Bosnia and Herzegovina against the Republika Srpska during Operation Mistral 2 in September, US President Bill Clinton announced a new peace initiative for Bosnia and Herzegovina. This initiative, which aimed to restore eastern Slavonia to Croatia, was based on Croatian sovereignty and the Z-4 Plan. Gailbraith sought to reconcile the plan with new circumstances in the field;[51] an example was limited self-government for Croatian Serbs in eastern Slavonian municipalities where they comprised a majority of the 1991 population; after Croatia objected, the proposal was replaced with provisions from the Constitution of Croatia. By early October the process led to the Erdut Agreement, establishing a framework for restoring eastern Slavonia to Croatian rule.[52] When the agreement was first implemented in 1996, there were concerns in Croatia that the process might result in "covert" implementation of the Z-4 Plan in eastern Slavonia and political autonomy for the region.[53]

The Z-4 Plan was again resurrected in 1999 as a template for the Rambouillet Agreement, a proposed peace treaty negotiated between FR Yugoslavia and ethnic Albanians living in Kosovo.[30] In 2005, after the Kosovo War, Serbia and Montenegro attempted to resolve the Kosovo status process by tabling a peace plan offering broad autonomy for Kosovo. According to Drašković, then foreign minister of Serbia and Montenegro, the plan was a "mirror image of the Z-4 Plan".[54] That year an "RSK government-in-exile" was set up in Belgrade, demanding the revival of the Z-4 Plan in Croatia (a move condemned by Drašković and Serbian President Boris Tadić).[55] The same idea was put forward in 2010 by a Serb refugee organisation led by Savo Štrbac.[56]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Sudetic & 19 August 1990.

- ^ ICTY & 12 June 2007.

- ^ Sudetic & 2 April 1991.

- ^ Engelberg & 3 March 1991.

- ^ Sudetic & 26 June 1991.

- ^ Sudetic & 29 June 1991.

- ^ Narodne novine & 8 October 1991.

- ^ EECIS 1999, pp. 272–278.

- ^ Bellamy & 10 October 1992.

- ^ Bjelajac & Žunec 2009, pp. 249–250.

- ^ Sudetic & 18 November 1991.

- ^ Armatta 2010, pp. 195–196.

- ^ CIA 2002, p. 106.

- ^ CIA 2002, p. 276.

- ^ a b c d Ahrens 2007, p. 165.

- ^ a b Marijan 2010, p. 358.

- ^ a b Bing 2007, note 72.

- ^ a b c Ahrens 2007, p. 159.

- ^ a b c d Ahrens 2007, p. 158.

- ^ Ramet 2006, p. 455.

- ^ Ahrens 2007, p. 182.

- ^ Ahrens 2007, p. 160.

- ^ Ahrens 2007, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Ahrens 2007, p. 161.

- ^ a b Ahrens 2007, p. 162.

- ^ Ahrens 2007, p. 114.

- ^ a b Ahrens 2007, p. 163.

- ^ Bing 2007, p. 391.

- ^ a b Bing 2007, p. 393.

- ^ a b Bing 2007, note 73.

- ^ Ahrens 2007, pp. 163–164.

- ^ a b c Marinković & 2 February 1995.

- ^ Ahrens 2007, p. 164.

- ^ Ahrens 2007, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Armatta 2010, p. 203.

- ^ a b c Ahrens 2007, p. 166.

- ^ Marijan 2010, pp. 221–222.

- ^ Marijan 2010, p. 17.

- ^ Marijan 2010, p. 16.

- ^ Ahrens 2007, p. 170.

- ^ a b Ahrens 2007, p. 171.

- ^ Sell 2002, p. 239.

- ^ Marijan 2010, p. 365.

- ^ Marijan & July 2010.

- ^ Ahrens 2007, pp. 171–172.

- ^ a b c Ahrens 2007, p. 172.

- ^ a b Ahrens 2007, p. 173.

- ^ Marijan 2010, p. 367.

- ^ Marijan 2010, p. 366.

- ^ Ahrens 2007, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Bing 2007, pp. 396–397.

- ^ Bing 2007, p. 398.

- ^ Pavić 1996, p. 170.

- ^ Didanović & 29 December 2005.

- ^ Index.hr & 5 March 2005.

- ^ Oslobođenje & 3 August 2010.

References

[edit]- Books

- Ahrens, Geert-Hinrich (2007). Diplomacy on the Edge: Containment of Ethnic Conflict and the Minorities Working Group of the Conferences on Yugoslavia. Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8557-0.

- Armatta, Judith (2010). Twilight of Impunity: The War Crimes Trial of Slobodan Milosevic. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4746-0.

- Bjelajac, Mile; Žunec, Ozren (2009). "The War in Croatia, 1991–1995". In Charles W. Ingrao; Thomas Allan Emmert (eds.). Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies: A Scholars' Initiative. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-533-7.

- Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Russian and European Analysis (2002). Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. ISBN 9780160664724. OCLC 50396958.

- Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. London, England: Routledge. 1999. ISBN 978-1-85743-058-5.

- Marijan, Davor (2010). Storm (PDF). Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Homeland War Memorial & Documentation Centre. ISBN 978-953-7439-25-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building And Legitimation, 1918–2006. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.

- Sell, Louis (2002). Slobodan Milosevic and the Destruction of Yugoslavia. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-3223-7.

- Štrbac, Savo (2015). Gone with the Storm: A Chronicle of Ethnic Cleansing of Serbs from Croatia. Knin-Banja Luka-Beograd: Grafid, DIC Veritas. ISBN 9789995589806.

- Scientific journal articles

- Bing, Albert (September 2007). "Put do Erduta – Položaj Hrvatske u međunarodnoj zajednici 1994.-1995. i reintegracija hrvatskog Podunavlja" [The Path to Erdut – Croatia's Position in the International Community 1994/1995 and the Reintegration of Croatian Danube Region (Podunavlje)]. Scrinia Slavonica (in Croatian). 7 (1). Slavonski Brod, Croatia: Croatian Historical Institute – Department of History of Slavonia, Srijem and Baranja: 371–404. ISSN 1332-4853.

- Pavić, Radovan (October 1996). "Problem dijela istočne Hrvatske: UNTAES – nada i realnost" [The Issue of Eastern Croatia: UNTAES – Between Hope and Reality]. Croatian Political Science Review (in Croatian). 33 (4). Zagreb, Croatia: University of Zagreb, Faculty of Political Science: 169–188. ISSN 0032-3241.

- News reports

- Bellamy, Christopher (10 October 1992). "Croatia built 'web of contacts' to evade weapons embargo". The Independent. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012.

- Didanović, Vera (29 December 2005). "Ministar u opoziciji" [Minister in Opposition]. Vreme (in Serbian).

- Engelberg, Stephen (3 March 1991). "Belgrade Sends Troops to Croatia Town". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013.

- Marinković, Gojko (2 February 1995). "Apsurdi oko Z-4" [Absurdity Regarding Z-4] (in Croatian). Alternativna Informativna Mreža.

- "Roads Sealed as Yugoslav Unrest Mounts". The New York Times. Reuters. 19 August 1990. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013.

- "Samozvana vlada pobunjenih Srba priziva Z4" [Self-styled Government of the Rebel Serbs Calls for Z-4] (in Croatian). Index.hr. 5 March 2005.

- "Srbi prognani iz Hrvatske o 15. obljetnici Oluje: Aktivirati plan Z4" [Serbs Banished from Croatia on the 15th Anniversary of the Storm: Activate the Z-4 Plan]. Oslobođenje (in Bosnian). 3 August 2010.

- Sudetic, Chuck (2 April 1991). "Rebel Serbs Complicate Rift on Yugoslav Unity". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013.

- Sudetic, Chuck (26 June 1991). "2 Yugoslav States Vote Independence To Press Demands". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012.

- Sudetic, Chuck (29 June 1991). "Conflict in Yugoslavia; 2 Yugoslav States Agree to Suspend Secession Process". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 June 2013.

- Sudetic, Chuck (18 November 1991). "Croats Concede Danube Town's Loss". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013.

- Other sources

- Marijan, Davor (July 2010). "Oluja – bitka svih bitaka" [Storm – Battle of all Battles]. Hrvatski vojnik (in Croatian). Zagreb, Croatia: Ministry of Defence. ISSN 1333-9036.

- "Odluka" [Decision]. Narodne novine (in Croatian) (53). Narodne novine. 8 October 1991. ISSN 1333-9273.

- "The Prosecutor vs. Milan Martic – Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 12 June 2007.