American football

Larry Fitzgerald (in blue) catches a pass while Cortland Finnegan (in red) plays defense at the 2009 Pro Bowl. | |

| Highest governing body | International Federation of American Football |

|---|---|

| Nicknames | |

| First played | November 6, 1869 New Brunswick, New Jersey, U.S. (Princeton vs. Rutgers) |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Full |

| Team members | 11 (both teams may freely substitute players between downs) |

| Type | |

| Equipment |

|

| Venue | Football field (rectangular: 120 yards long, 53+1⁄3 yards wide) |

| Glossary | Glossary of American football |

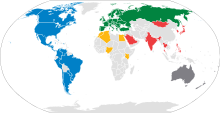

| Presence | |

| Country or region | Worldwide (most popular in North America) |

| Olympic | Demonstrated at the 1904 and 1932 Summer Olympics, flag football at the 2028 Summer Olympics |

| World Games | Invitational sport at 2005, 2017, and 2022 (flag football) Games |

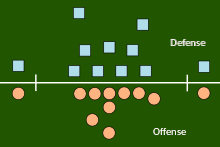

American football, referred to simply as football in the United States and Canada and also known as gridiron football,[nb 1] is a team sport played by two teams of eleven players on a rectangular field with goalposts at each end. The offense, the team with possession of the oval-shaped football, attempts to advance down the field by running with the ball or throwing it, while the defense, the team without possession of the ball, aims to stop the offense's advance and to take control of the ball for themselves. The offense must advance the ball at least ten yards in four downs or plays; if they fail, they turn over the football to the defense, but if they succeed, they are given a new set of four downs to continue the drive. Points are scored primarily by advancing the ball into the opposing team's end zone for a touchdown or kicking the ball through the opponent's goalposts for a field goal. The team with the most points at the end of the game wins.

American football evolved in the United States, originating from the sports of soccer and rugby.[3] The first American football game was played on November 6, 1869, between two college teams, Rutgers and Princeton, using rules based on the rules of soccer at the time. A set of rule changes drawn up from 1880 onward by Walter Camp, the "Father of American Football", established the snap, the line of scrimmage, eleven-player teams, and the concept of downs. Later rule changes legalized the forward pass, created the neutral zone, and specified the size and shape of the football. The sport is closely related to Canadian football, which evolved in parallel with and at the same time as the American game, although its rules were developed independently from those of Camp. Most of the features that distinguish American football from rugby and soccer are also present in Canadian football. The two sports are considered the primary variants of gridiron football.

American football is the most popular sport in the United States in terms of broadcast viewership audience. The most popular forms of the game are professional and college football, with the other major levels being high-school and youth football. As of 2022[update], nearly 1.04 million high-school athletes play the sport in the U.S., with another 81,000 college athletes in the NCAA and the NAIA.[4] The National Football League (NFL) has the highest average attendance of any professional sports league in the world. Its championship game, the Super Bowl, ranks among the most-watched club sporting events globally. In 2022, the league had an annual revenue of around $18.6 billion,[5] making it the most valuable sports league in the world.[6] Other professional and amateur leagues exist worldwide, but the sport does not have the international popularity of other American sports like baseball or basketball; the sport maintains a growing following in the rest of North America, Europe, Brazil, and Japan.

Etymology and names

In the United States, American football is referred to as "football".[7] The term "football" was officially established in the rulebook for the 1876 college football season, when the sport first shifted from soccer-style rules to rugby-style rules. Although it could easily have been called "rugby" at this point, Harvard, one of the primary proponents of the rugby-style game, compromised and did not request the name of the sport be changed to "rugby".[8] The terms "gridiron" or "American football" are favored in English-speaking countries where other types of football are popular, such as the United Kingdom, Ireland, New Zealand, and Australia.[9][10]

History

| Part of the American football series on the |

| History of American football |

|---|

| Origins of American football |

| Close relations to other codes |

| Topics |

Early history

American football evolved from the sports of rugby and soccer. Rugby, like American football, is a sport in which two competing teams vie for control of a ball, which can be kicked through a set of goalposts or run into the opponent's goal area to score points.[11]

What is considered to be the first American football game was played on November 6, 1869, between Rutgers and Princeton, two college teams. They consisted of 25 players per team and used a round ball that could not be picked up or carried. It could, however, be kicked or batted with the feet, hands, head, or sides, with the objective being to advance it into the opponent's goal. Rutgers won the game 6–4.[12][13] Collegiate play continued for several years with games played using the rules of the host school. Representatives of Yale, Columbia, Princeton and Rutgers met on October 19, 1873, to create a standard set of rules for use by all schools. Teams were set at 20 players each, and fields of 400 by 250 feet (122 m × 76 m) were specified. Harvard abstained from the conference, as they favored a rugby-style game that allowed running with the ball.[13] After playing McGill University using both American (known as "the Boston game") for the first game and Canadian (rugby) rules for the second one,[13][14] the Harvard players preferred the Canadian style of having only 11 men on the field, running the ball without having to be chased by an opponent, the forward pass, tackling, and using an oblong instead of a round ball.[15][16]

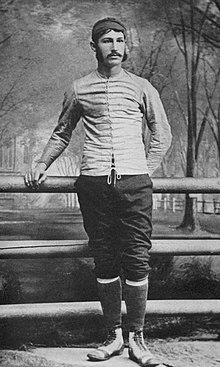

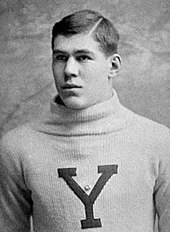

An 1875 Harvard–Yale game played under rugby-style rules was observed by two Princeton athletes who were impressed by it. They introduced the sport to Princeton, a feat the Professional Football Researchers Association compared to "selling refrigerators to Eskimos".[13] Princeton, Harvard, Yale, and Columbia then agreed to intercollegiate play using a form of rugby union rules with a modified scoring system.[17] These schools formed the Intercollegiate Football Association, although Yale did not join until 1879. Yale player Walter Camp, now regarded as the "Father of American Football",[17][18] secured rule changes in 1880 that reduced the size of each team from 15 to 11 players and instituted the snap to replace the chaotic and inconsistent scrum.[17] While the game between Rutgers and Princeton is commonly considered the first American football game, several years prior in 1862, the Oneida Football Club formed as the oldest known football club in the United States. The team consisted of graduates of Boston's elite preparatory schools and played from 1862 to 1865.[19]

Evolution of the game

The introduction of the snap resulted in an unexpected consequence. Before the snap, the strategy had been to punt if a scrum resulted in bad field position. However, a group of Princeton players realized that, as the snap was uncontested, they could now hold the ball indefinitely to prevent their opponent from scoring. In 1881, in a game between Yale and Princeton, both teams used this strategy to maintain their undefeated records. Each team held the ball, gaining no ground, for an entire half, resulting in a 0–0 tie. This "block game" proved extremely unpopular with both teams' spectators and fans.[17]

A rule change was necessary to prevent this strategy from taking hold, and a reversion to the scrum was considered. However, Camp successfully proposed a rule in 1882 that limited each team to three downs, or tackles, to advance the ball 5 yards (4.6 m). Failure to advance the ball the required distance within those three downs would result in control of the ball being forfeited to the other team. This change effectively made American football a separate sport from rugby, and the resulting five-yard lines added to the field to measure distances made it resemble a gridiron in appearance. Other major rule changes included a reduction of the field size to 110 by 53+1⁄3 yards (100.6 m × 48.8 m) and the adoption of a scoring system that awarded four points for a touchdown, two for a safety and a goal following a touchdown, and five for a goal from the field. Additionally, tackling below the waist was legalized,[17] and a static line of scrimmage was instituted.[20]

Despite these new rules, football remained a violent sport. Dangerous mass-formations like the flying wedge resulted in serious injuries and deaths.[21] A 1905 peak of 19 fatalities nationwide resulted in a threat by President Theodore Roosevelt to abolish the game unless major changes were made.[22] In response, 62 colleges and universities met in New York City to discuss rule changes on December 28, 1905. These proceedings resulted in the formation of the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States, later renamed the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA).[23]

The legal forward pass was introduced in 1906, although its effect was initially minimal due to the restrictions placed on its use. The idea of a 40-yard-wider field was opposed by Harvard due to the size of the new Harvard Stadium.[24] Other rule changes introduced that year included the reduction of playing time from 70 to 60 minutes and an increase of the distance required for a first down from 5 to 10 yards (4.6 to 9.1 m). To reduce infighting and dirty play between teams, the neutral zone was created along the width of the football before the snap.[25] Scoring was also adjusted: points awarded for field goals were reduced to three in 1909[18] and points for touchdowns were raised to six in 1912.[26] Also in 1912, the field was shortened to 100 yards (91 m) long, two 10-yard-long (9.1 m) end zones were created, and teams were given four downs instead of three to advance the ball 10 yards (9.1 m).[27][28] The roughing the passer penalty was implemented in 1914, and eligible players were first allowed to catch the ball anywhere on the field in 1918.[29]

Professional era

On November 12, 1892, Pudge Heffelfinger was paid $500 (equivalent to $16,956 in 2023) to play a game for the Allegheny Athletic Association against the Pittsburgh Athletic Club. This is the first recorded instance of a player being paid to participate in a game of American football, although many athletic clubs in the 1880s offered indirect benefits, such as helping players attain employment, giving out trophies or watches that players could pawn for money, or paying double in expense money. Despite these extra benefits, the game had a strict sense of amateurism at the time, and direct payment to players was frowned upon, if not prohibited outright.[30]

Over time, professional play became increasingly common, and with it came rising salaries and unpredictable player movement, as well as the illegal payment of college players who were still in school. The National Football League (NFL), a group of professional teams that was originally established in 1920 as the American Professional Football Association, aimed to solve these problems. This new league's stated goals included an end to bidding wars over players, prevention of the use of college players, and abolition of the practice of paying players to leave another team.[31] By 1922, the NFL had established itself as America's premier professional football league.[32]

The dominant form of football at the time was played at the collegiate level. The upstart NFL received a boost to its legitimacy in 1925, however, when an NFL team, the Pottsville Maroons, defeated a team of Notre Dame all-stars in an exhibition game.[33] A greater emphasis on the passing game helped professional football to distinguish itself further from the college game during the late 1930s.[31] Football, in general, became increasingly popular following the 1958 NFL Championship game between the Baltimore Colts and the New York Giants, still referred to as the "Greatest Game Ever Played". The game, a 23–17 overtime victory by the Colts, was seen by millions of television viewers and had a major influence on the popularity of the sport. This, along with the innovations introduced by the new American Football League (AFL) in the early 1960s, helped football to become the most popular sport in the United States by the mid-1960s.[34]

The rival AFL arose in 1960 and challenged the NFL's dominance. The AFL began in relative obscurity but eventually thrived, with an initial television contract with the ABC television network. The AFL's existence forced the conservative NFL to expand to Dallas and Minnesota in an attempt to destroy the new league. Meanwhile, the AFL introduced many new features to professional football in the United States: official time was kept on a scoreboard clock rather than on a watch in the referee's pocket, as the NFL did; optional two-point conversions by pass or run after touchdowns; names on the jerseys of players; and several others, including expansion of the role of minority players, actively recruited by the league in contrast to the NFL. The AFL also signed several star college players who had also been drafted by NFL teams. Competition for players heated up in 1965, when the AFL New York Jets signed rookie Joe Namath to a then-record $437,000 contract (equivalent to $4.23 million in 2023). A five-year, $40 million NBC television contract followed, which helped to sustain the young league. The bidding war for players ended in 1966 when NFL owners approached the AFL regarding a merger, and the two leagues agreed on one that took full effect in 1970. This agreement provided for a common draft that would take place each year, and it instituted an annual World Championship game to be played between the champions of each league. This championship game began play at the end of the 1966 season. Once the merger was completed, it was no longer a championship game between two leagues and reverted to the NFL championship game, which came to be known as the Super Bowl.[35]

College football maintained a tradition of postseason bowl games. Each bowl game was associated with a particular conference and earning a spot in a bowl game was the reward for winning a conference. This arrangement was profitable, but it tended to prevent the two top-ranked teams from meeting in a true national championship game, as they would normally be committed to the bowl games of their respective conferences. Several systems have been used since 1992 to determine a national champion of college football. The first was the Bowl Coalition, in place from 1992 to 1994. This was replaced in 1995 by the Bowl Alliance, which gave way to the Bowl Championship Series (BCS) in 1997.[36] The BCS arrangement proved to be controversial, and was replaced in 2014 by the College Football Playoff (CFP).[37][38]

Teams and positions

A football game is played between two teams of 11 players each.[39][40][41] Playing with more on the field is punishable by a penalty.[39][42][43] Teams may substitute any number of their players between downs;[44][45][46] this "platoon" system replaced the original system, which featured limited substitution rules, and has resulted in teams utilizing specialized offensive, defensive and special teams units.[47] The number of players allowed on an active roster varies by league; the NFL has a 53-man roster,[48] while NCAA Division I allows teams to have 63 scholarship players in the FCS and 85 scholarship players in the FBS, respectively.[49]

Individual players in a football game must be designated with a uniform number between 1 and 99, though some teams may "retire" certain numbers, making them unavailable to players. NFL teams are required to number their players by a league-approved numbering system, and any exceptions must be approved by the commissioner.[39] NCAA and NFHS teams are "strongly advised" to number their offensive players according to a league-suggested numbering scheme.[50][51]

Although the sport is played almost exclusively by men, women are eligible to play in high school, college, and professional football. No woman has ever played in the NFL, but women have played in high school and college football games.[52] In 2018, 1,100 of the 225,000 players in Pop Warner Little Scholars youth football were girls, and around 11% of the 5.5 million Americans who report playing tackle football are female according to the Sports and Fitness Industry Association.[53]

Offensive unit

The role of the offensive unit is to advance the football down the field with the ultimate goal of scoring a touchdown.[54]

The offensive team must line up in a legal formation before they can snap the ball. An offensive formation is considered illegal if there are more than four players in the backfield or fewer than five players numbered 50–79 on the offensive line.[40][55][56] Players can line up temporarily in a position whose eligibility is different from what their number permits as long as they report the change immediately to the referee, who then informs the defensive team of the change.[57] Neither team's players, except the center (C), are allowed to line up in or cross the neutral zone until the ball is snapped. Interior offensive linemen are not allowed to move until the snap of the ball.[58]

The main backfield positions are the quarterback (QB), halfback/tailback (HB/TB), and fullback (FB). The quarterback is the leader of the offense. Either the quarterback or a coach calls the plays. Quarterbacks typically inform the rest of the offense of the play in the huddle before the team lines up. The quarterback lines up behind the center to take the snap and then hands the ball off, throws it, or runs with it.[54]

The primary role of the halfback, also known as the running back or tailback, is to carry the ball on running plays. Halfbacks may also serve as receivers. Fullbacks tend to be larger than halfbacks and function primarily as blockers, but they are sometimes used as runners in short-yardage or goal-line situations.[59] They are seldom used as receivers.[60]

The offensive line (OL) consists of several players whose primary function is to block members of the defensive line from tackling the ball carrier on running plays or sacking the quarterback on passing plays.[59] The leader of the offensive line is the center, who is responsible for snapping the ball to the quarterback, blocking,[59] and for making sure that the other linemen do their jobs during the play.[61] On either side of the center are the guards (G), while tackles (T) line up outside the guards.

The principal receivers are the wide receivers (WR) and the tight ends (TE).[62] Wide receivers line up on or near the line of scrimmage, split outside the line. The main goal of the wide receiver is to catch passes thrown by the quarterback,[59] but they may also function as decoys or as blockers during running plays. Tight ends line up outside the tackles and function both as receivers and as blockers.[59]

Defensive unit

The role of the defense is to prevent the offense from scoring by tackling the ball carrier or by forcing turnovers. Turnovers include interceptions (a defender catching a forward pass intended for the offense) and forced fumbles (taking possession of the ball from the ball-carrier).[54]

The defensive line (DL) consists of defensive ends (DE) and defensive tackles (DT). Defensive ends line up on the ends of the line, while defensive tackles line up inside, between the defensive ends. The primary responsibilities of defensive ends and defensive tackles are to stop running plays on the outside and inside, respectively, to pressure the quarterback on passing plays, and to occupy the line so that the linebackers can break through.[59]

Linebackers line up behind the defensive line but in front of the defensive backfield. They are divided into two types: middle linebackers (MLB) and outside linebackers (OLB). Linebackers tend to serve as the defensive leaders and call the defensive plays, given their vantage point of the offensive backfield. Their roles include defending the run, pressuring the quarterback, and tackling backs, wide receivers, and tight ends in the passing game.[63]

The defensive backfield, often called the secondary, consists of cornerbacks (CB) and safeties (S). Safeties are themselves divided into free safeties (FS) and strong safeties (SS).[59] Cornerbacks line up outside the defensive formation, typically opposite a receiver to be able to cover them. Safeties line up between the cornerbacks but farther back in the secondary. Safeties tend to be viewed as "the last line of defense" and are responsible for stopping deep passing plays as well as breakout running plays.[59]

Special teams unit

The special teams unit is responsible for all kicking plays. The special teams unit of the team in control of the ball tries to execute field goal (FG) attempts, punts, and kickoffs, while the opposing team's unit will aim to block or return them.[54]

Three positions are specific to the field goal and PAT (point-after-touchdown) unit: the placekicker (K or PK), holder (H), and long snapper (LS). The long snapper's job is to snap the football to the holder, who will catch and position it for the placekicker. There is not usually a holder on kickoffs, because the ball is kicked off a tee; however, a holder may be used in certain situations, such as if wind is preventing the ball from remaining upright on the tee. The player on the receiving team who catches the ball is known as the kickoff returner (KR).[64]

The positions specific to punt plays are the punter (P), long snapper, upback, and gunner. The long snapper snaps the football directly to the punter, who then drops and kicks it before it hits the ground. Gunners line up split outside the line and race down the field, aiming to tackle the punt returner (PR)—the player who catches the punt. Upbacks line up a short distance behind the line of scrimmage, providing additional protection to the punter.[65]

Rules

Scoring

In football, the winner is the team that has scored more points at the end of the game. There are multiple ways to score in a football game. The touchdown (TD), worth six points, is the most valuable scoring play in American football. A touchdown is scored when a live ball is advanced into, caught, or recovered in the opposing team's end zone.[54] The scoring team then attempts a try, more commonly known as the point(s)-after-touchdown (PAT) or conversion, which is a single scoring opportunity. This is generally attempted from the two- or three-yard line, depending on the level of play. If the PAT is scored by a place kick or drop kick through the goal posts, it is worth one point, typically called the extra point. If the PAT is scored by what would normally be a touchdown, it is worth two points; this is known as a two-point conversion. In general, the extra point is almost always successful, while the two-point conversion is a much riskier play with a higher probability of failure; accordingly, extra point attempts are far more common than two-point conversion attempts.[66]

A field goal (FG), worth three points, is scored when the ball is place kicked or drop kicked through the uprights and over the crossbars of the defense's goalposts.[67][68][69] In practice, almost all field goal attempts are done via place kick. While drop kicks were common in the early days of the sport, the shape of modern footballs makes it difficult to reliably drop kick the ball. The last successful scoring play by drop kick in the NFL was accomplished in 2006; prior to that, the last successful drop kick had been made in 1941.[70] After a PAT attempt or successful field goal, the scoring team must kick the ball off to the other team.[71]

A safety is scored when the ball carrier is tackled in the carrier's own end zone. Safeties are worth two points, which are awarded to the defense.[54] In addition, the team that conceded the safety must kick the ball to the scoring team via a free kick.[72]

Field and equipment

Football games are played on a rectangular field that measures 120 yards (110 m) long and 53+1⁄3 yards (48.8 m) wide. Lines marked along the ends and sides of the field are known as the end lines and sidelines. Goal lines are marked 10 yards (9.1 m) inward from each end line.[73][74][75]

Weighted pylons are placed the sidelines on the inside corner of the intersections with the goal lines and end lines. White markings on the field identify the distance from the end zone. Inbound lines, or hash marks, are short parallel lines that mark off 1-yard (0.91 m) increments. Yard lines, which can run the width of the field, are marked every 5 yards (4.6 m). A one-yard-wide line is placed at each end of the field; this line is marked at the center of the two-yard line in professional play and at the three-yard line in college play. Numerals that display the distance from the closest goal line in yards are placed on both sides of the field every ten yards.[73][74][75]

Goalposts are located at the center of the plane of the two end lines. The crossbar of these posts is 10 feet (3.0 m) above the ground, with vertical uprights at the end of the crossbar 18 feet 6 inches (5.64 m) apart for professional and collegiate play, and 23 feet 4 inches (7.11 m) apart for high school play.[76][77][78] The uprights extend vertically 35 feet (11 m) on professional fields, a minimum of 10 yards (9.1 m) on college fields, and a minimum of 10 feet (3.0 m) on high school fields. Goal posts are padded at the base, and orange ribbons are normally placed at the tip of each upright as indicators of wind strength and direction.[76][77][78]

The football itself is a prolate spheroid leather ball, similar to the balls used in rugby or Australian rules football.[79] To contain the compressed air within it, a pig's bladder was commonly used before the advent of artificial rubber inside the leather outer shell to sustain crushing forces.[80][81] At all levels of play, the football is inflated to 12+1⁄2 to 13+1⁄2 psi (86 to 93 kPa), or just under one atmosphere, and weighs 14 to 15 ounces (400 to 430 g);[78][82][83] beyond that, the exact dimensions vary slightly. In professional play the ball has a long axis of 11 to 11+1⁄4 inches (28 to 29 cm), a long circumference of 28 to 28+1⁄2 inches (71 to 72 cm), and a short circumference of 21 to 21+1⁄4 inches (53 to 54 cm).[84] In college and high school play the ball has a long axis of 10+7⁄8 to 11+7⁄16 inches (27.6 to 29.1 cm), a long circumference of 27+3⁄4 to 28+1⁄2 inches (70 to 72 cm), and a short circumference of 20+3⁄4 to 21+1⁄4 inches (53 to 54 cm).[78][82]

Duration and time stoppages

Football games last for a total of 60 minutes in professional and college play and are divided into two halves of 30 minutes and four quarters of 15 minutes.[85][86] High school football games are 48 minutes in length with two halves of 24 minutes and four quarters of 12 minutes.[87] The two halves are separated by a halftime period, and the first and third quarters are followed by a short break.[85][86][88] Before the game starts, the referee and each team's captain meet at midfield for a coin toss. The visiting team can call either "heads" or "tails"; the winner of the toss chooses whether to receive or kick off the ball or which goal they wish to defend. They can defer their choice until the second half. Unless the winning team decides to defer, the losing team chooses the option the winning team did not select—to receive, kick, or select a goal to defend to begin the second half. Most teams choose to receive or defer, because choosing to kick the ball to start the game allows the other team to choose which goal to defend.[89] Teams switch goals following the first and third quarters.[90] If a down is in progress when a quarter ends, play continues until the down is completed.[91][92][93] If certain fouls are committed during play while time has expired, the quarter may be extended through an untimed down.[94]

Games last longer than their defined length due to play stoppages—the average NFL game lasts slightly over three hours.[95] Time in a football game is measured by the game clock. An operator is responsible for starting, stopping and operating the game clock based on the direction of the appropriate official.[85][96] A separate play clock is used to show the amount of time within which the offense must initiate a play. The play clock is set to 25 seconds after certain administrative stoppages in play and to 40 seconds when play is proceeding without such stoppages. If the offense fails to start a play before the play clock reads "00", a delay of game foul is called on the offense.[91][97][98]

Advancing the ball and downs

There are two main ways the offense can advance the ball: running and passing. In a typical play, the center passes the ball backwards and between their legs to the quarterback in a process known as the snap. The quarterback then either hands the ball off to a running back, throws the ball, or runs with it. The play ends when the player with the ball is tackled or goes out-of-bounds or a pass hits the ground without a player having caught it. A forward pass can be legally attempted only if the passer is behind the line of scrimmage; only one forward pass can be attempted per down.[71] As in rugby, players can also pass the ball backwards at any point during a play.[99] In the NFL, a down also ends immediately if the runner's helmet comes off.[100]

The offense is given a series of four plays, known as downs. If the offense advances ten or more yards in the four downs, they are awarded a new set of four downs. If they fail to advance ten yards, possession of the football is turned over to the defense. In most situations, if the offense reaches their fourth down they will punt the ball to the other team, which forces them to begin their drive from farther down the field; if they are in field goal range, they might attempt to score a field goal instead.[71] A group of officials, the chain crew, keeps track of both the downs and the distance measurements.[101] On television, a yellow line is electronically superimposed on the field to show the first down line to the viewing audience.[102]

Kicking

There are two categories of kicks in football: scrimmage kicks, which can be executed by the offensive team on any down from behind or on the line of scrimmage,[105][106][107] and free kicks.[108][109][110] The free kicks are the kickoff, which starts the first and third quarters and overtime and follows a try attempt or a successful field goal; the safety kick follows a safety.[106][111][112]

On a kickoff, the ball is placed at the 35-yard line of the kicking team in professional and college play and at the 40-yard line in high school play. The ball may be drop kicked or place kicked. If a place kick is chosen, the ball can be placed on the ground or a tee; a holder may be used in either case. On a safety kick, the kicking team kicks the ball from their own 20-yard line. They can punt, drop kick or place kick the ball, but a tee may not be used in professional play. Any member of the receiving team may catch or advance the ball. The ball may be recovered by the kicking team once it has gone at least ten yards and has touched the ground or has been touched by any member of the receiving team.[113][114][115]

The three types of scrimmage kicks are place kicks, drop kicks, and punts. Only place kicks and drop kicks can score points.[67][68][69] The place kick is the standard method used to score points,[103] because the pointy shape of the football makes it difficult to reliably drop kick.[103][104] Once the ball has been kicked from a scrimmage kick, it can be advanced by the kicking team only if it is caught or recovered behind the line of scrimmage. If it is touched or recovered by the kicking team beyond this line, it becomes dead at the spot where it was touched.[116][117][118] The kicking team is prohibited from interfering with the receiver's opportunity to catch the ball. The receiving team has the option of signaling for a fair catch, which prohibits the defense from blocking into or tackling the receiver. The play ends as soon as the ball is caught, and the ball may not be advanced.[119][120][121]

Officials and fouls

Officials are responsible for enforcing game rules and monitoring the clock. All officials carry a whistle and wear black-and-white striped shirts and black hats except for the referee, whose hat is white. Each carries a weighted yellow flag that is thrown to the ground to signal that a foul has been called. An official who spots multiple fouls will throw their hat as a secondary signal.[122] Women can serve as officials; Sarah Thomas became the NFL's first female official in 2015.[123] The seven officials (of a standard seven-man crew; lower levels of play up to the college level use fewer officials) on the field are each tasked with a different set of responsibilities:[122]

- The referee is positioned behind and to the side of the offensive backs. The referee is charged with oversight and control of the game and is the authority on the score, the down number, and any rule interpretations in discussions among the other officials. The referee announces all penalties and discusses the infraction with the offending team's captain, monitors for illegal hits against the quarterback, makes requests for first-down measurements, and notifies the head coach whenever a player is ejected. The referee positions themselves to the passing arm side of the quarterback. In most games, the referee is responsible for spotting the football prior to a play from scrimmage.

- The umpire is positioned in the defensive backfield, except in the NFL, where the umpire is positioned lateral to the referee on the opposite side of the formation. The umpire watches play along the line of scrimmage to make sure that no more than 11 offensive players are on the field before the snap, and that no offensive linemen are illegally downfield on pass plays. The umpire monitors contact between offensive and defensive linemen and calls most of the holding penalties. The umpire records the number of timeouts taken and the winner of the coin toss and game score. They also assist the referee in situations involving possession of the ball close to the line of scrimmage, determines whether player equipment is legal, and dries wet balls prior to the snap if a game is played in rain.

- The back judge is positioned deep in the defensive backfield, behind the umpire. The back judge ensures that the defensive team has no more than 11 players on the field and determines whether catches are legal, whether field goal or extra point attempts are good, and whether a pass interference violation occurred. The back judge is also responsible for the play clock, the time between each play, when a visible play clock is not used.

- The head linesman/down judge is positioned on one end of the line of scrimmage. The head linesman/down judge watches for any line-of-scrimmage and illegal use-of-hands violations and assists the line judge with illegal shift or illegal motion calls. The head linesman/down judge also rules on out-of-bounds calls that happen on their side of the field, oversees the chain crew, and marks the forward progress of a runner when a play has been whistled dead.

- The side judge is positioned twenty yards downfield of the head linesman. The side judge mainly duplicates the functions of the field judge. On field goal and extra point attempts, the side judge is positioned lateral to the umpire.

- The line judge is positioned on the end of the line of scrimmage, opposite the head linesman. They supervise player substitutions, the line of scrimmage during punts, and game timing. The line judge notifies the referee when time has expired at the end of a quarter and notifies the head coach of the home team when five minutes remain for halftime. In the NFL, the line judge also alerts the referee when two minutes remain in the half. If the clock malfunctions or becomes inoperable, the line judge becomes the official timekeeper.

- The field judge is positioned twenty yards downfield from the line judge. The field judge monitors and controls the play clock, counts the number of defensive players on the field, and watches for offensive pass interference and illegal use-of-hands violations by offensive players. The field judge also makes decisions regarding catches, recoveries, the ball spot when a player goes out of bounds, and illegal touching of fumbled balls that have crossed the line of scrimmage. On field goal and extra point attempts, the field judge is stationed under the upright opposite the back judge.

- The center judge is an eighth official used only in the top level of college football. The center judge stands lateral to the referee, the same way the umpire does in the NFL. The center judge is responsible for spotting the football after each play and has many of the same responsibilities as the referee, except announcing penalties.

Another set of officials, the chain crew, are responsible for moving the chains. The chains, consisting of two large sticks with a 10-yard-long chain between them, are used to measure for a first down. The chain crew stays on the sidelines during the game, but if requested by the officials they will briefly bring the chains on to the field to measure. A typical chain crew will have at least three people—two members of the chain crew will hold either of the two sticks, while a third will hold the down marker. The down marker, a large stick with a dial on it, is flipped after each play to indicate the current down and is typically moved to the approximate spot of the ball. The chain crew system has been used for over 100 years and is considered an accurate measure of distance, rarely subject to criticism from either side.[101]

Safety and brain health

Football is a full-contact sport, and injuries are relatively common. Most injuries occur during training sessions, particularly ones that involve contact between players.[124] To try to prevent injuries, players are required to wear a set of equipment. At a minimum players must wear a football helmet and a set of shoulder pads, but individual leagues may require additional padding such as thigh pads and guards, knee pads, chest protectors, and mouthguards.[125][126][127] Most injuries occur in the lower extremities, particularly in the knee, but a significant number also affect the upper extremities. The most common types of injuries are strains, sprains, bruises, fractures, dislocations, and concussions.[124]

Repeated concussions (and possibly sub-concussive head impacts[128]) can increase a person's risk in later life for CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy) and health issues such as dementia, Parkinson's disease, and depression.[129] Concussions are often caused by helmet-to-helmet or upper-body contact between opposing players, although helmets have prevented more serious injuries such as skull fractures.[130] Various programs are aiming to reduce concussions by reducing the frequency of helmet-to-helmet hits; USA Football's "Heads Up Football" program aims to reduce concussions in youth football by teaching coaches and players about the signs of a concussion, the proper way to wear football equipment and ensure it fits, and proper tackling methods that avoid helmet-to-helmet contact.[131] However, a study in the Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine found that Heads Up Football was ineffective; the same study noted that more extensive reforms implemented by Pop Warner Little Scholars and its member teams were effective in significantly reducing concussion rates.[132]

A 2018 study performed by the VA Boston Healthcare System and the Boston University School of Medicine found that tackle football before age 12 was correlated with earlier onset of symptoms of CTE, but not with symptom severity. More specifically, each year a player played tackle football under age 12 predicted earlier onset of cognitive, behavioral, and mood problems by an average of two and a half years.[133][134][135]

Leagues and tournaments

The National Football League (NFL) and the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) are the most popular football leagues in the United States.[136] The National Football League was founded in 1920[137] and has since become the largest and most popular sport in the United States.[138] The NFL has the highest average attendance of any sporting league in the world, with an average attendance of 66,960 during the 2011 NFL season.[139] The NFL championship game is called the Super Bowl, and is among the biggest events in club sports worldwide.[140] It is played between the champions of the National Football Conference (NFC) and the American Football Conference (AFC), and its winner is awarded the Vince Lombardi Trophy.[141]

College football is the third-most popular sport in the United States, behind professional baseball and professional football.[142] The NCAA, the largest collegiate organization, is divided into three Divisions: Division I, Division II and Division III.[143] Division I football is further divided into two subdivisions: the Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) and the Football Championship Subdivision (FCS).[144] The champions of each level of play are determined through NCAA-sanctioned playoff systems; while the champion of Division I-FBS was historically determined by various polls and ranking systems, the subdivision adopted a four-team playoff system in 2014.[145]

High school football is the most popular sport in the United States played by boys; over 1.1 million boys participated in the sport from 2007 to 2008 according to a survey by the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS). There is a stark contrast in youth football participation between boys and girls. Only one youth football league exists in the United States for girls, the GFL. The NFHS is the largest organization for high school football, with member associations in all 50 states as well as the District of Columbia. USA Football is the governing body for youth and amateur football,[146] and Pop Warner Little Scholars is the largest organization for youth football.[147]

Other professional leagues

Rival leagues

The most successful league to directly compete with the NFL was the American Football League (AFL), which existed from 1960 to 1969. The AFL became a significant rival in 1964 before signing a five-year, US$36 million television deal with NBC. AFL teams began signing NFL players to contracts, and the league's popularity grew to challenge that of the NFL. The two leagues merged in the 1970 season, and all the AFL teams joined the NFL. An earlier league, the All-America Football Conference (AAFC), was in play from 1946 to 1949. After it had dissolved, two AAFC teams, the Cleveland Browns and the San Francisco 49ers, became members of the NFL; another member, the Baltimore Colts joined the league, but folded after just a year in the NFL.[148]

Other attempts to start rival leagues since the AFL merged with the NFL in 1970 have been far less successful, as professional football salaries and the NFL's television contracts began to escalate out of the reach of competitors and the NFL covered more of the larger cities. The World Football League (WFL) played for two seasons, in 1974 and 1975, but faced such severe monetary issues it could not pay its players. In its second and final season the WFL attempted to establish a stable credit rating, but the league disbanded before the season could be completed.[149] The United States Football League (USFL) operated for three seasons from 1983 to 1985. Originally not intended as a rival league, the entry of owners who sought marquee talent and to challenge the NFL led to an escalation in salaries and ensuing financial losses. A subsequent US$1.5 billion antitrust lawsuit against the NFL was successful in court, but the league was awarded only $1 in damages, which was automatically tripled to $3 under antitrust law.[150]

Complementary national leagues

The original XFL, created in 2001 by Vince McMahon, lasted for only one season. Despite television contracts with NBC and UPN, and high expectations, the XFL suffered from low quality of play and poor reception for its use of tawdry professional wrestling gimmicks, which caused initially high ratings and attendance to collapse.[151] The XFL was rebooted in 2020.[152] However, after only five weeks of play, the league's operations slowly came to a close due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic,[153] and filed for bankruptcy on April 13.[154] The United Football League (UFL) began in 2009 but folded after suspending its 2012 season amid declining interest and lack of major television coverage.[155] The Alliance of American Football lasted less than one season, unable to keep investors.[156]

International play

American football leagues exist throughout the world, but the game has yet to achieve the international success and popularity of baseball and basketball.[157] It is not an Olympic sport, but it was a demonstration sport at the 1932 Summer Olympics.[158] At the international level, Canada, Mexico, and Japan are considered to be second-tier, while Austria, Germany, and France would rank among a third tier. These countries rank far below the United States, which is dominant at the international level.[159]

NFL Europa, the developmental league of the NFL, operated from 1991 to 1992 and then from 1995 to 2007. At the time of its closure, NFL Europa had five teams based in Germany and one in the Netherlands.[160] In Germany, the German Football League (GFL) has 16 teams and has operated for over 40 seasons, with the league's championship game, the German Bowl, closing out each season. The league operates in a promotion and relegation structure with German Football League 2 (GFL2), which also has 16 teams.[161] The BIG6 European Football League functions as a continental championship for Europe. The competition is contested between the top six European teams.[161]

The United Kingdom also operated several teams within NFL Europe during the League's tenure.[162] The resulting rise in popularity of the sport brought the NFL back to the country in 2007 where they now hold the NFL International Series in London, currently consisting of four regular season games.[163][164] The continuing interest and growth in both the sport and the series has led to the possible formation of a potential NFL franchise in London[165][166][167]

An American football league system already exists within the UK, the BAFANL, which has run under various guises since 1983. It currently has 70 teams operating across the tiers of contact football in which teams aim to earn promotion to the Division above, with the Premier Division teams competing to win the Britbowl, the annual British Football Bowl game that has been played since 1985.[168][169][170] In 2007, the British Universities American Football League was formed. From 2008, the BUAFL was officially associated with the National Football League (NFL), through its partner organization NFL UK.[171] In 2012, BUAFL's league and teams were absorbed into BUCS after American football became an official BUCS sport.[172] Over the period 2007 to 2014, the BUAFL grew from 42 teams and 2,460 participants to 75 teams and over 4,100 people involved.[173]

American football federations are present in Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe, and Oceania; a total of 75 national football federations exist as of 2023[update].[174] The International Federation of American Football (IFAF), an international governing body composed of continental federations, runs tournaments such as the IFAF World Championship, the IFAF Women's World Championship, the IFAF U-19 World Championship, and the Flag Football World Championship. The IFAF also organizes the annual International Bowl game.[175] The IFAF has received provisional recognition from the International Olympic Committee (IOC).[176] Several major obstacles hinder the IFAF goal of achieving status as an Olympic sport. These include the predominant participation of men in international play and the short three-week Olympic schedule. Large team sizes are an additional difficulty, due to the Olympics' set limit of 10,500 athletes and coaches. American football also has an issue with a lack of global visibility. Nigel Melville, the CEO of USA Rugby, noted that "American football is recognized globally as a sport, but it's not played globally." To solve these concerns, major effort has been put into promoting flag football, a modified version of American football, at the international level.[159] Flag football has been shortlisted for appearance at the 2028 Summer Olympics, pending final approval by the International Olympic Committee.[177]

Popularity and cultural influence

United States

"Baseball is still called the national pastime, but football is by far the more popular sport in American society", according to ESPN.com's Sean McAdam.[178] In a 2014 poll conducted by Harris Interactive, professional football ranked as the most popular sport, and college football ranked third behind only professional football and baseball; 46% of participants ranked some form of the game as their favorite sport. Professional football has ranked as the most popular sport in the poll since 1985, when it surpassed baseball for the first time.[179] Professional football is most popular among those who live in the eastern United States and rural areas, while college football is most popular in the southern United States and among people with graduate and post-graduate degrees.[180] Football is also the most-played sport by high school and college athletes in the United States. As of 2022[update], the National Football Foundation reports nearly 1.04 million high-school athletes play the sport, with another 81,000 college athletes across both the NCAA and the NAIA;[4] in comparison, the second-most played sport, basketball, had around 920,000 participants in high school and 63,000 in college.[181]

The Super Bowl is the most popular single-day sporting event in the United States,[35] and is among the biggest club sporting events in the world in terms of TV viewership.[140] The NFL made approximately $12 billion in revenue in 2022.[182] Super Bowl games account for eight of the top ten most-watched broadcasts in American history; Super Bowl LVII, played on February 12, 2023, was watched by a record 115.1 million Americans,[183] and is second only to the Apollo 11 moon landing (125 million viewers).[184]

American football also plays a significant role in American culture. The day on which the Super Bowl is held is considered a de facto national holiday,[185] and in parts of the country like Texas, the sport has been compared to a religion.[186][187] Football is also linked to other holidays; New Year's Day is traditionally the date for several college football bowl games, including the Rose Bowl. However, if New Year's Day is on a Sunday, the bowl games are moved to another date so as not to conflict with the typical NFL Sunday schedule.[188] Thanksgiving football is another American tradition,[189] hosting many high school, college, and professional games.[190] Implicit rules such as playing through pain and sacrificing for the better of the team are promoted in football culture.[191]

Other countries

In Canada, the game has a significant following. According to a 2013 poll, 21% of respondents said they followed the NFL "very closely" or "fairly closely", making it the third-most followed league behind the National Hockey League (NHL) and Canadian Football League (CFL).[192] American football also has a long history in Mexico, which was introduced to the sport in 1896. It was the second-most popular sport in Mexico in the 1950s, with the game being particularly popular in colleges.[193] The Los Angeles Times notes the NFL claims over 16 million fans in Mexico, which places the country third behind the U.S. and Canada.[194] American football is played in Mexico both professionally and as part of the college sports system.[195] A professional league, the Liga de Fútbol Americano Profesional (LFA), was founded in 2016.[196]

Japan was introduced to the sport in 1934 by Paul Rusch, a teacher and Christian missionary who helped to establish football teams at three universities in Tokyo.[197] Play was halted during World War II by order of Emperor Hirohito, but the sport began growing in popularity again after the war.[198] As of 2010[update], there are more than 400 high school football teams in Japan, with over 15,000 participants, and over 100 teams play in the Kantoh Collegiate Football Association (KCFA).[197] The X-League is the largest American football league in Japan, and the largest American football league in the world to use a promotion-relegation system. Some teams in the X-League, like the Panasonic Impulse, are sponsored by corporations, and all Japanese players on these teams are employed by the corporation. The league operates in separate spring and fall seasons, with each team playing five games. The top eight teams make the playoffs, which are played in Tokyo Dome; the champion is determined by the Rice Bowl.[198]

Europe is a major target for the expansion of the game by football organizers. In the United Kingdom in the 1980s, the sport was popular, with the 1986 Super Bowl being watched by over four million people (about 1 out of every 14 Britons). Its popularity faded during the 1990s, coinciding with the establishment of the Premier League—top level of the English football league system. According to BBC America, there is a "social stigma" surrounding American football in the UK, with many Brits feeling the sport has no right to call itself "football" due to the lack of emphasis on kicking.[199] Nonetheless, the sport has retained a following in the United Kingdom; the NFL operates a media network in the country, and since 2007 has hosted the NFL International Series in London. Super Bowl viewership has also rebounded, with over 4.4 million Britons watching Super Bowl XLVI.[200] The sport is played in European countries like Switzerland, which has American football clubs in every major city,[201] and Germany, where the sport has around 45,000 registered amateur players.[195]

In Brazil, football is a growing sport. It was generally unknown there until the 1980s when a small group of players began playing on Copacabana Beach in Rio de Janeiro. The sport grew gradually with 700 amateur players registering within 20 years. Games were played on the beach with modified rules and without the traditional football equipment due to its lack of availability in Brazil. Eventually, a tournament, the Carioca championship, was founded, with the championship Carioca Bowl played to determine a league champion. The country saw its first full-pad game of football in October 2008.[202] According to The Rio Times, the sport is one of the fastest-growing sports in Brazil and is almost as commonly played as soccer on the beaches of Copacabana and Botafogo.[203]

Football in Brazil is governed by the Confederação Brasileira de Futebol Americano (CBFA), which had over 5,000 registered players as of November 2013. The sport's increase in popularity has been attributed to games aired on ESPN, which began airing in Brazil in 1992 with Portuguese commentary.[204] The popularity and "easy accessibility" of non-contact versions of the sport in Brazil has led to a rise in participation by female players.[203] According to ESPN, the American football audience in Brazil increased 800% between 2013 and 2016. The network, along with Esporte Interativo, airs games there on cable television. The NFL has expressed interest in having games in the country, and the Super Bowl has become a widely watched event in Brazil at bars and movie theaters.[205]

Further countries have also expressed interest in football to lesser degrees. The Arab world has expressed growing interest in American football, with many countries in the region being members of IFAF Asia. Jordan and the United Arab Emirates, which are not members of IFAF, have established their own domestic leagues. Egypt established two leagues for the sport, namely the Egyptian League of American Football and the Egyptian Federation of American Football, and Saudi Arabia hosts two teams based out of Jeddah and Yanbu respectively.[206][207] China has additionally been a target for the expansion of the sport, with the Mainland being the home of the Chinese National Football League as well as a growing audience of Super Bowl watchers. Three franchises are also based out of Hong Kong, which prior to the COVID-19 pandemic regularly played mainland teams. NFL games average 900,000 viewers in China, though the league has cited logistical challenges which would prevent teams from playing games akin to abroad games in European countries.[208]

Variations and related sports

Canadian football, the predominant form of football in Canada, is closely related to American football—both sports developed from rugby and are considered to be the chief variants of gridiron football.[209] Although both games share a similar set of rules, there are several key rule differences: for example, in Canadian football the field measures 150 by 65 yards (137 by 59 m), including two 20-yard end zones (for a distance between goal lines of 110 yards),[210] teams have three downs instead of four, there are twelve players on each side instead of eleven,[211] fair catches are not allowed, and a rouge, worth a single point is scored if the offensive team kicks the ball out of the defense's end zone.[212] The Canadian Football League (CFL) is the major Canadian league and is the second-most popular sporting league in Canada, behind the National Hockey League.[212] The NFL and CFL had a formal working relationship from 1997 to 2006.[213] The CFL has a strategic partnership with two American football leagues, the German Football League (GFL) and the Liga de Futbol Americano Profesional (LFA).[214] The Canadian rules were developed separately from the American game.

Indoor football leagues constitute what The New York Times writer Mike Tanier described as the "most minor of minor leagues." Leagues are unstable, with franchises regularly moving from one league to another or merging with other teams, and teams or entire leagues dissolving completely; games are only attended by a small number of fans, and most players are semi-professional athletes. The Indoor Football League is an example of a prominent indoor league.[215] The Arena Football League, which was founded in 1987 and ceased operations in 2019, was one of the longest-lived indoor football leagues.[216] In 2004, the league was called "America's fifth major sport" by ESPN The Magazine.[217]

There are several non-contact variants of football, such as flag football.[218] In flag football the ball-carrier is not tackled; instead, defenders aim to pull a flag tied around the ball-carrier's waist.[219] Another variant, touch football, simply requires the ball-carrier to be touched to be considered downed. Depending on the rules used, a game of touch football may require the ball-carrier be touched with either one or two hands to be considered downed.[220]

See also

- American football strategy

- Comparison of American football and rugby union

- Comparison of American football and rugby league

- Fantasy football (gridiron)

- List of American football films

- Lists of American football players

- List of American football stadiums by capacity

- List of American and Canadian football leagues

- List of female gridiron football players

- Doping in American football

- Women's gridiron football

Notes

- ^ The terms "gridiron football", "gridiron", and "grid" are sometimes used as synonyms for American football.[1] They are also used in a broader sense that includes Canadian football, a football code that is very similar to American football.[2]

Footnotes

- ^ "Gridiron" Archived November 7, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, MacMillan Dictionary

- ^ "gridiron football (sport)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. britannica.com. Archived from the original on June 14, 2010. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- ^ "Nov 12 Birth of pro football | Pro Football Hall of Fame". pfhof. Archived from the original on August 20, 2024. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ a b "Football by the Numbers". National Football Foundation. July 25, 2023. Archived from the original on August 20, 2024. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ "NFL revenue 2022". Statista. Archived from the original on August 20, 2024. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ Ozanian, Mike. "The World's 50 Most Valuable Sports Teams 2023". Forbes. Archived from the original on January 19, 2024. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ Peralta, Eyder (June 10, 2010). "Football Or Soccer? What's In A Name?". NPR. Archived from the original on October 1, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ Nelson 1993, pp. 15, 22.

- ^ Geoghegan, Tim (May 27, 2013). "'In the six' and football's other strange Americanisms". BBC News. Archived from the original on June 9, 2013. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ Huntsdale, Justin (June 13, 2012). "Living off the grid: American football in coastal Australia". Australian Broadcasting Company. Archived from the original on October 28, 2013. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ "The basics of rugby union". BBC. September 2005. Archived from the original on March 1, 2014. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ "Rutgers – The Birthplace of Intercollegiate Football". Rutgers University. Archived from the original on September 24, 2014. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "No Christian End! The Beginnings of Football in America" (PDF). Professional Football Researchers Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- ^ "Foot Ball" Archived August 20, 2024, at the Wayback Machine, clipping from The Boston Post, May 16, 1874, p. 3

- ^ "History- May 14, 1874 How Canada created American football". rcinet.ca. May 14, 2015. Archived from the original on October 9, 2018. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ "This Date in History: First football game was May 14, 1874". mcgill.ca. Archived from the original on June 29, 2018. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Camp and His Followers" (PDF). Professional Football Researchers Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 18, 2015. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- ^ a b "NFL History 1869–1910". NFL.com. Archived from the original on January 2, 2008. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- ^ "Remembering the first high school football games" Archived November 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine on The Boston Globe, November 21, 2012

- ^ "Walter Camp and the Birth of Modern Football". New England Historical Society. November 28, 2013. Archived from the original on October 26, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

As a senior at Yale, Camp prevailed at Massasoit House and cut the number of players to 11 from 15. That year [1882] he also came up with the idea for a static line of scrimmage.

- ^ Bennett (1976), p. 20.

- ^ Lewis, Guy M. (1969). "Teddy Roosevelt's Role in the 1905 Football Controversy". The Research Quarterly. 40: 717–724.

- ^ "The History of the NCAA". National Collegiate Athletic Association. Archived from the original on April 30, 2007. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- ^ "Saturday Night Lights: Harvard Stadium Joins the 21st Century". New York Times. September 22, 2007. Archived from the original on May 29, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ Braunwart, Bob; Carroll, Bob. "Blondy Wallace and the Biggest Football Scandal Ever: 1906" (PDF). The Coffin Corner. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2014. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- ^ "NFL History 1911–1920". NFL.com. Archived from the original on January 15, 2008. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- ^ Spick Hall (September 15, 1912). "Commodores Face The Hardest Schedule For Many Long Years". The Tennessean. p. 19. Archived from the original on August 13, 2016. Retrieved June 17, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Danzig, Allison (1956). The History of American Football: Its Great Teams, Players, and Coaches. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall. pp. 70–71.

- ^ Vancil (2000), p. 22.

- ^ "The Birth of Pro Football". Pro Football Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on November 16, 2006. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ a b Clary, Jack (1994). "The First 25 Years" (PDF). The Coffin Corner. 16 (4): 1, 4–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2014.

- ^ Jozsa (2004), pp. 270.

- ^ Nelson, Robert (January 11, 2007). "The Curse". Phoenix New Times. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- ^ "Greatest game ever played". Pro Football Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- ^ a b Clary, Jack (1994). "The Second 25 Years" (PDF). The Coffin Corner. 16 (5): 4–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 19, 2014.

- ^ "BCS Chronology". bcsfootball.org. FOX Sports on MSN. 2006. Archived from the original on January 13, 2010. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ Wojciechowski, Jean (June 26, 2012). "Presidents get playoff plan right". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- ^ Russo, Ralph D. (January 2, 2015). "NCAA College Football Playoff pits powerhouses Ohio State and Oregon". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on January 6, 2015. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ a b c NFL Rules 2012, p. 21.

- ^ a b NCAA Rules 2011–2012, p. 15.

- ^ NFHS Rules 2012, p. 11.

- ^ NCAA Rules 2011–2012, p. 107.

- ^ NFHS Rules 2012, pp. 71–72.

- ^ NFL Rules 2012, pp. 21–22.

- ^ NCAA Rules 2011–2012, pp. 53–54.

- ^ NFHS Rules 2012, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Dickson, James David (July 14, 2010). "The innovator". Michigan Today. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- ^ Lillibridge, Marc (May 16, 2023). "The Anatomy of a 53-Man Roster in the NFL". Bleacher Report. Archived from the original on August 20, 2024. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ Staff, Max Olson (October 4, 2023). "NCAA votes to eliminate annual initial counter limits". The Athletic. Archived from the original on August 20, 2024. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ NCAA Rules 2011–2012, pp. 21–22.

- ^ NFHS Rules 2012, pp. 16–17.

- ^ McManus, Jane (May 11, 2011). "For women, tackling NFL is a long shot". ESPNW. Archived from the original on August 10, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- ^ de la Cretaz, Britni (February 2, 2018). "More Girls Are Playing Football. Is That Progress?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 10, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "NFL in a nutshell". BBC Sport. October 19, 2005. Archived from the original on November 22, 2012. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- ^ NFL Rules 2012, pp. 21–24.

- ^ NFHS Rules 2012, pp. 57–58.

- ^ NFL Rules 2012, pp. 36, 40.

- ^ Long, Howie; Czarnecki, John. "Common Penalties in American Football". Dummies.com. Archived from the original on December 23, 2012. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Football Players' Roles in Team Offense and Defense". Dummies.com. Archived from the original on January 6, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- ^ Pasquarelli, Len (June 1, 2010). "Fullbacks back en vogue". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ^ Wood, Ryan (October 23, 2009). "Centers: The Unsung Heroes of Football". Active.com. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ^ Long, Howie; Czarnecki, John. "Football's Offensive Team: The Receivers". Dummies.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2013. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ^ Long, Howie; Czarnecki, John. "Football's Defensive Team: The Linebackers". Dummies.com. Archived from the original on January 22, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- ^ Long, Howie; Czarnecki, John. "The Role of Special Teams in a Football Game". Dummies.com. Archived from the original on January 24, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ^ Long, Howie; Czarnecki, John. "Football Special Teams: Players on a Punt Team". Dummies.com. Archived from the original on January 26, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ^ Sackrowitz, Harold (2000). "Refining the Point(s)-After-Touchdown Decision" (PDF). Department of Statistical Science. 13 (3): 29–30, 33–34. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 2, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ^ a b NFL Rules 2012, pp. 57–59.

- ^ a b NCAA Rules 2011–2012, pp. 79–80.

- ^ a b NFHS Rules 2012, p. 66.

- ^ "The last dropkick". Pro Football Hall of Fame. December 6, 2015. Archived from the original on August 20, 2024. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Beginner's Guide to Football". National Football League. Archived from the original on February 16, 2011. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ NFL Rules 2012, p. 60

- ^ a b NFL Rules 2012, p. v, 1.

- ^ a b NCAA Rules 2011–2012, pp. 18–19, 23–24.

- ^ a b NFHS Rules 2012, pp. 11–12, 13, 28.

- ^ a b NFL Rules 2012, p. 2.

- ^ a b NCAA Rules 2011–2012, p. 18.

- ^ a b c d NFHS Rules 2012, p. 14.

- ^ Cross, Rod (August 2010). "Bounce of an oval shaped football". Sports Technology. 3 (3): 168–180. doi:10.1080/19346182.2011.564283. ISSN 1934-6190. S2CID 108409393. Archived from the original on February 15, 2022. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- ^ "How a Cow Becomes a Football". January 31, 2019. Archived from the original on August 20, 2024. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ "History of Footballs | the First Football | Pendle Sportswear Blog". December 20, 2019. Archived from the original on August 20, 2024. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ a b NCAA Rules 2011–2012, p. 20.

- ^ NFL Rules 2012, p. 3.

- ^ "Official Playing Rules of the National Football League" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016., p.3

- ^ a b c NFL Rules 2012, p. 14.

- ^ a b NCAA Rules 2011–2012, p. 45.

- ^ NFHS Rules 2012, pp. 38–39.

- ^ NFHS Rules 2012, p. 39.

- ^ Easterbrook, Gregg (September 4, 2008). "TMQ's all-haiku NFL preview". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ^ "How Football Game Time Is Measured in Quarters". Dummies.com. Archived from the original on November 26, 2012. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ^ a b NFL Rules 2012, pp. 14–18

- ^ NCAA Rules 2011–2012, pp. 47–53.

- ^ NFHS Rules 2012, pp. 38–45

- ^ Wire, Adam (October 9, 2017). "Ask the official: Extra-point ruling and untimed downs". USA Football. Archived from the original on January 25, 2024. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ McCarthy, Michael (October 27, 2011). "Delay of game: NFL games running longer in 2011". USA Today. Archived from the original on July 7, 2013. Retrieved December 3, 2012.

- ^ NCAA Rules 2011–2012, pp. 16, 41.

- ^ NCAA Rules 2011–2012, pp. 41, 46–47.

- ^ NFHS Rules 2019.

- ^ "Backward pass". National Football League. Archived from the original on January 23, 2017.

- ^ Smith, Michael David (November 16, 2013). "When a runner's helmet comes off, he's down". Profootballtalk.com. Archived from the original on October 19, 2014. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ a b Branch, John (December 31, 2008). "The Orchestration of the Chain Gang". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 29, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ St. John, Allan (December 18, 2009). "The Tech Behind the Football's Broadcast-Only First Down Line". Popular Mechanics. Archived from the original on December 13, 2012. Retrieved November 2, 2012.

- ^ a b c Hogrogian, John (1999). "The Last Drop Kick?" (PDF). The Coffin Corner. 21 (6). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 18, 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2012.

- ^ a b "Dropkick_diagram". Pro Football Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved October 8, 2012.

- ^ NFL Rules 2012, p. 50.

- ^ a b NCAA Rules 2011–2012, p. 34.

- ^ NFHS Rules 2012, p. 32.

- ^ NFL Rules 2012, p. 6.

- ^ NCAA Rules 2011–2012, p. 30.

- ^ NFHS Rules 2012, p. 27.

- ^ NFL Rules 2012, pp. 8–9.

- ^ NFHS Rules 2012, pp. 31–32.

- ^ NFL Rules 2012, pp. 29–30.

- ^ NCAA Rules 2011–2012, pp. 61–64.

- ^ NFHS Rules 2012, pp. 15, 46, 52–53.

- ^ NFL Rules 2012, pp. 33–34, 50–53.

- ^ NCAA Rules 2011–2012, pp. 55–56, 63–64.

- ^ NFHS Rules 2012, pp. 49, 53–54.

- ^ NFL Rules 2012, pp. 7, 54–55.

- ^ NCAA Rules 2011–2012, pp. 30, 66–67.

- ^ NFHS Rules 2012, pp. 27, 56.

- ^ a b Long, Howie; Czarnecki, John. "American Football Officials". Dummies.com. Archived from the original on November 27, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ^ Fox, Ashley (April 17, 2015). "Meet Sarah Thomas, NFL's first female official". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on August 10, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- ^ a b Saal JA (August 1991). "Common American football injuries". Sports Medicine. 12 (2): 132–47. doi:10.2165/00007256-199112020-00005. PMID 1947533. S2CID 45077919.

- ^ NFL Rules 2012, pp. 24–27.

- ^ NCAA Rules 2011–2012, p. 22.

- ^ NFHS Rules 2012, pp. 17–19.

- ^ "Repeated Head Hits, Not Just Concussions, May Lead To A Type Of Chronic Brain Damage". NPR.org. Archived from the original on January 20, 2018. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- ^ Maiese, Kenneth (January 2008). "Concussion". The Merck Manual Home – Health Handbook. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ^ Gregory, Sean (October 22, 2010). "Can Football Finally Tackle Its Injury Problem?". Time. Archived from the original on January 13, 2013. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ "Heads Up Football". USA Football. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- ^ Schwarz, Alan (July 27, 2016). "N.F.L.-Backed Youth Program Says It Reduced Concussions. The Data Disagrees". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 8, 2017.

- ^ "Study finds youth football tied to earlier symptoms of CTE". ESPN. April 30, 2018. Archived from the original on June 23, 2018. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- ^ Villalpando, Nicole (May 25, 2018). "Parents, put off tackle football as long as possible, study suggests". Austin American-Statesman. Archived from the original on June 23, 2018.

- ^ Alosco, Michael L.; Mez, Jesse; Tripodis, Yorghos; Kiernan, Patrick T.; Abdolmohammadi, Bobak; Murphy, Lauren; Kowall, Neil W.; Stein, Thor D.; Huber, Bertrand Russell; Goldstein, Lee E.; Cantu, Robert C.; Katz, Douglas I.; Chaisson, Christine E.; Martin, Brett; Solomon, Todd M. (2018). "Age of first exposure to tackle football and chronic traumatic encephalopathy". Annals of Neurology. 83 (5): 886–901. doi:10.1002/ana.25245. PMC 6367933. PMID 29710395.

- ^ Fentress, Andrew (May 18, 2012). "New version of United States Football League aims to succeed where others have failed". Oregon Live. Advance Internet. Archived from the original on July 9, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

- ^ "NFL founded in Canton". Pro Football Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ^ Chin, Andrew (November 25, 2012). "China fast catching American football fever with 10 teams formed". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ^ "And the silver goes to ..." The Economist. September 27, 2011. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ^ a b Harris, Nick (January 31, 2010). "Elite clubs on Uefa gravy train as Super Bowl knocked off perch". The Independent. Archived from the original on November 19, 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ^ George, Shannon (September 10, 2009). "Let's Learn About: The Vince Lombardi Trophy". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

- ^ "Football is America's Favorite Sport as Lead Over Baseball Continues to Grow". Harris Interactive. January 25, 2005. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ^ "About the NCAA". NCAA.org. Archived from the original on January 18, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

- ^ "Differences Among the Three Divisions: Division I". NCAA.org. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

- ^ "Postseason Football". NCAA.org. Archived from the original on May 22, 2012. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

- ^ Alic, Steve (April 4, 2009). "NFHS and USA Football Create Football Coaching Course". USA Football. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- ^ O'Connor, Anahad (June 12, 2012). "Trying to Reduce Head Injuries, Youth Football Limits Practices". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- ^ Cross, B. Duane (January 22, 2001). "Off-the-field competition yields game-changing merger". CNNSI. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- ^ Johnson, William Oscar (December 1, 1975). "The Day The Money Ran Out". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ Somers, Kent (August 7, 2008). "Twenty years later, USFL still brings fond memories". USA Today. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (May 11, 2001). "No More Springtimes for the XFL as League Folds". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ Pascale, Jordan (February 7, 2020). "The XFL Aims To Capitalize On Spring Football With 9-Point Touchdowns, Other Oddities". NPR.org. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.