Waterloo Village, New Jersey

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2017) |

Waterloo Village | |

Canal Museum, Canal Society of New Jersey, 2018 | |

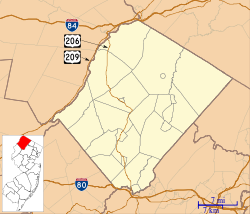

| Location | Byram Township, New Jersey |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°54′56″N 74°45′22″W / 40.91556°N 74.75611°W |

| Area | 70 acres (28 ha) |

| Built | 1820 |

| Architectural style | Late Victorian |

| NRHP reference No. | 77000909[1] (original) 15000176 (increase) |

| NJRHP No. | 2593[2] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | September 13, 1977 |

| Boundary increase | April 28, 2015 |

| Designated NJRHP | February 3, 1977 |

Waterloo Village is a restored 19th-century canal town in Byram Township, Sussex County (west of Stanhope) in northwestern New Jersey, United States. The community was approximately the half-way point in the roughly 102 miles (164 km) trip along the Morris Canal, which ran from Jersey City (across the Hudson River from Manhattan, New York) to Phillipsburg, New Jersey, (across the Delaware River from Easton, Pennsylvania). Waterloo possessed all the accommodations necessary to service the needs of a canal operation, including an inn, a general store, a church, a blacksmith shop (to service the mules on the canal), and a watermill. For canal workers, Waterloo's geographic location would have been conducive to being an overnight stopover point on the two-day trip between Phillipsburg and Jersey City.

It is currently an open-air museum in Allamuchy Mountain State Park. As part of the State Park, it is open to the public from sunrise to sunset. The village was added to the National Register of Historic Places on September 13, 1977.[3]

Canal and railroad eras

[edit]Opened in 1831, the Morris Canal's traffic volume, which was primarily anthracite coal from Pennsylvania, peaked during the late 1860s, shortly after the end of the American Civil War. Up until that time, the local railroads — the Lackawanna Railroad's Sussex Branch and Morris and Essex Railroad — had only supplemented the canal's operation, rather than competing with it. Both railroads ran within a short distance of the village. After the War, the canal's traffic began to quickly shift over to the much faster and more reliable railroad. It was expected that during most winters the canal would be frozen solid, and thus impassable during the time when its chief commodity was in greatest demand.[citation needed]

As a result, the canal underwent a steady decline, and so did Waterloo Village. Although the canal was not officially abandoned until 1924, rarely did more than one boat a year (to fulfill the conditions of the canal's charter) run through the canal after 1900. By the time of the Great Depression, Waterloo Village had been abandoned by its original owners.

Unheralded saviors

[edit]The village's location, within a short distance of the Lackawanna Railroad (which had to overcome a steep eastbound grade towards New York near Waterloo, slowing freight trains to a crawl as they labored up the hill to Netcong), made it easy for hobos to jump on and off boxcars.

The hobos, as it turned out, found Waterloo and adopted it as a stopping off point on their cross-country journey towards New York.[4] This new purpose for the village wasn't all that different from its original purpose a century earlier. The hobos protected Waterloo Village by occupying it throughout the 1930s and '40s. The original Waterloo railroad station was moved from the station site during the 1940s and became a private residence on U.S. Route 206 in Mount Olive Township, New Jersey.[5]

Rebirth

[edit]Percival 'Percy' Leach established the not-for-profit Waterloo Foundation for the Arts to finance the restoration of the village in 1967.[6] Leach and his partner in the interior design business Lou Gualandi turned it into a living history tourist attraction with working blacksmiths, potters, candle dippers and weavers demonstrated crafts from the colonial historic eras.

The village would eventually become part of New Jersey's Allamuchy Mountain State Park.[7][when?]

Admissions fees being never enough to cover the administrative costs of the attraction, the partners sought out corporate and state grants, but ultimately opened an open-air concert field on the property in 1977 to raise funds.

Notable acts who have performed at Waterloo include Muddy Waters, Johnny Cash, the Beach Boys, Steppenwolf, the Allman Brothers, America, Arlo Guthrie, Phish, Chicago, Roy Orbison, Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Indigo Girls, Edie Brickell, Melissa Etheridge, Joe Cocker, The Moody Blues, Blues Traveler, Ray Charles, "Weird Al" Yankovic, Blue Öyster Cult and three Lollapalooza tours.[8] In addition to pop and rock concerts, Waterloo has also hosted craft shows, ethnic festivals, conventions, Metropolitan Opera, jazz, classical music and the Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival.[9][10][11]

Controversy, downfall, and closure

[edit]Following Gualandi's death in 1988, Leach became involved in several controversies that brought greater scrutiny upon the Waterloo Foundation for the Arts. The most controversial was the so-called "land swap" that allowed BASF corporation to build a large corporate headquarters on land that had once been part of Allamuchy Mountain State Park.[12] The Waterloo board of directors subsequently brought in a new management team and throughout the mid-to-late 1990s tried to rebuild trust in the running of the village.[citation needed]

In 1995, a concert-goer died at a Phish concert that had attracted 30,000 people even though only 18,000 tickets were sold.[13][14] Events like this had completely overwhelmed the area's limited access roads and caused considerable friction with the surrounding towns. The foundation began downsizing the concerts around this time.

In the period from 2003 to 2006, the Waterloo Foundation for the Arts had received $900,000 from the State of New Jersey for general expenses, along with more than $300,000 since 2000 to cover repairs. As the state showed increasing displeasure with the village's operation, the $250,000 the group had expected to receive, which would have been used towards the $2 million operating budget for the site, was cut from the 2007 state budget. Waterloo Village was shut down in December 2006, except for the privately owned Waterloo United Methodist Church, which has a small but dedicated congregation and continues to operate as it has for over 150 years. In the period beginning in 2006, the Village was only open intermittently.[15]

Percy Leach died in 2007 leaving the organization's future uncertain.[16]

Reopening

[edit]Since the closing, several organizations have continued to restore aspects of the village. Friends of Waterloo and the Canal Society focused on Canal Town while a non profit called Winakung at Waterloo Inc. focused on the sustainability of the Lenape Indian Village.[17]

Through a concession agreement with the NJDEP Division of Parks and Forestry in 2014, group tours and programs became available at the village by reservation.[18] Winakung at Waterloo Inc. educational programs meet core curriculum standards and are ideal for school trips, scout groups, and summer camp field trips. Winakung at Waterloo Inc. also offers year-round outreach programs for schools, libraries, historical societies, Clean Communities, and more.[19]

In the spring of 2014, a 10-year lease (with the option of 10 more) was awarded to Jeffrey Miller Catering (JAM Catering) out of Philadelphia, making them the exclusive caterer for Waterloo Village.[20] JAM has renovated the Meeting House and Pavilion.[21]

Beginning May 2014, the SMS Italian Festival, an annual Non-Profit event supporting the children of St Michael School, began at the village.[22][23]

In May 2017, the stage was demolished to prepare for future festivals and make way for a new stage to be built on the grounds.[24][25]

United Methodist Church

[edit]The cornerstone for the Waterloo Village United Methodist Church was set on August 9, 1859, and the church was dedicated on February 9, 1860. General John Smith was the first to be buried in the churchyard cemetery.[26]

Gallery

[edit]-

Peter D. Smith House

-

Smith Homestead House

-

Smith's General Store, by the Morris Canal

-

A small aqueduct crosses the old canal lock

-

Blacksmith Shop

-

Ruins of the towpath bridge from the Morris Canal, Inclined Plane 4 West

-

Historic view of the inclined plane

-

United Methodist Church

See also

[edit]- National Register of Historic Places listings in Sussex County, New Jersey

- List of museums in New Jersey

References

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ "New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places - Sussex County" (PDF). NJ DEP - Historic Preservation Office. June 14, 2018. p. 1. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Waterloo". National Park Service. Retrieved September 5, 2018. With accompanying pictures

- ^ Giles, John R. (July 29, 2014). The Story of Waterloo Village: From Colonial Forge to Canal Town. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62585-210-6.

- ^ Waterloo Village is about 3⁄10 mile (0.48 km) off to the right, although Interstate 80 has since been built in between. The Sussex Branch Railroad once originated here and almost immediately passed over the inclined plane of the canal located near Waterloo on the trip to Branchville. Due to the branch's obsolete westerly alignment (facing away from the photographer, for coal shipments from Pennsylvania) the branch's connection with the mainline was moved to Netcong in 1903 to better serve passengers going towards New York, but further isolating the bucolic hamlet of Waterloo.

- ^ Hevesi, Dennis (March 2, 2007). "Percival Leach, 80, Savior of a Crumbling Village, Dies". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ "Waterloo Village at Allamuchy Mountain State Park". VisitNJ.org. April 18, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ Messenger, Erica Gooch, John Seyler, Dorothy U. (2013). Argument!. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-338402-3. OCLC 894574185.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ New Jersey Off the Beaten Path, 8th. Rowman & Littlefield. 2000. ISBN 978-0-7627-5228-7.

- ^ "Festival Background". www.dodgepoetry.org. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ Collins, Glenn (October 26, 1993). "Met Opera Planning Summer Season In New Jersey in '96". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ Depalma, Anthony (December 21, 1989). "New Jersey Gives Up Park Land in Swap With Developer". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ "Phish Article in Baltimore Sun". www.gadiel.com. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ MTV News Staff. "Twin Tragedies At Phish Concerts". MTV News. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ Hughes, Jennifer V. (February 18, 2007). "Mothballed 19th-Century Village Waits for Revival". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ "The continued existence of Waterloo Village hangs in the balance-www.njmonthly.com". New Jersey Monthly. December 19, 2007. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ Iannitelli, Giulia (February 26, 2011). "Welcome to Winakung at Waterloo – "Place of Sassafras."". nj. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ Iannitelli, Giulia (February 26, 2011). "Welcome to Winakung at Waterloo – "Place of Sassafras."". nj. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ "Home". winakungatwaterloo.com.

- ^ "Jeffrey A. Miller – Waterloo Village". jamcater.com. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ "New life at old Waterloo Village". Daily Record. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ "Saint Michael School Italian Festival". NJ Italian Heritage Commission. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ "SMS Italian Festival (@SMSitalianfest)". Retrieved February 26, 2020 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Old Waterloo concert stage falls, new concert venue planned". New Jersey Herald. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ Novak, Steve (May 5, 2017). "Waterloo Village concert stage torn down, setting scene for future fests". lehighvalleylive. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ "History". waterloo. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

External links

[edit] Media related to Waterloo Village at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Waterloo Village at Wikimedia Commons- Winakung at Waterloo Inc. Fully Guided and Interpreted Educational Tours of Waterloo Village and Winakung, the recreated Lenape Native American Village

- Canal Society of New Jersey

- NJ Dept. of Parks & Forests - Information on 2008 events at Waterloo Village

- Allamuchy Mountain State Park

- Allamuchy parks

- Waterloo United Methodist Church

- Museums in Sussex County, New Jersey

- Native American museums in New Jersey

- Ghost towns in New Jersey

- Open-air museums in New Jersey

- History museums in New Jersey

- Byram Township, New Jersey

- New Jersey Register of Historic Places

- National Register of Historic Places in Sussex County, New Jersey

- Historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places in New Jersey

- Event venues established in 1977