Washington–Rawson

Washington–Rawson was a neighborhood of Atlanta, Georgia. It included what is now Center Parc Stadium (formerly Turner Field) and the large parking lot to its north, until 1997 the site of Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium, as well as the I-20-Downtown Connector interchange. Washington and Rawson streets intersected where the interchange is today. To the northwest was Downtown Atlanta, to the west Mechanicsville, to the east Summerhill, and to the south Washington Heights, now called Peoplestown.

Fine residential district

[edit]

By the mid-1870s, Washington Street was becoming one of the city's finest residential streets.[1] The neighborhood was wealthy at the turn of the twentieth century: Encyclopædia Britannica of 1910 listed Washington Street as one of the finest residential areas of the city, along with Peachtree Street, Ponce de Leon Circle (now Ponce de Leon Avenue in Midtown) and Inman Park. Mansions included those of governor and senator Joseph E. Brown, his brother, attorney Julius L. Brown, restaurant owner Henry R. Durand, and fertilizer magnate and Standard Club co-founder Isaac Schoen.

Center of Jewish community

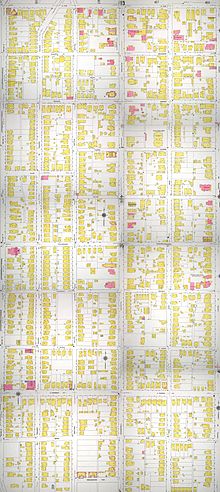

[edit]Sanborn fire insurance maps from 1911 confirm that the area was a center of Jewish community in Atlanta at the time:

- the reform Hebrew Benevolent Congregation synagogue (1902) was located at S. Pryor and Richardson streets (it would move to Ansley Park in 1931)

- Beth Israel Synagogue (orthodox)

- the Standard Club, a Jewish gentlemen's club, now located in Johns Creek in the northern suburbs

- the Hebrew (or Jewish) Orphans' Home was at the south end at 478 Washington St. SE (SE corner of Love St.)

The neighborhood was also home to the Convent of the Immaculate Conception, and to Piedmont Sanitorium, which would become the original Piedmont Hospital.

Decline and razing

[edit]

With the advent of the electric streetcar in the 1890s and then the automobile, wealthy Atlantans flocked to new, leafy neighborhoods like Ansley Park and Druid Hills and the southside soon became unfashionable. The Standard Club moved to Ponce de Leon Avenue in Midtown in 1929. By the 1950s the neighborhood had fallen on hard times and was targeted for "aggressive" urban renewal. It was at this time that the term "Washington–Rawson" was used for the area. Prior to that, most references to the area were references to individual streets, intersections or directionals (e.g. south side). The western side of Washington–Rawson neighborhood was leveled in the 1950s to construct the Downtown Connector, reducing the neighborhood by half.[2]

Some sources state the leveling of the neighborhood for the stadium was part of Mayor Ivan Allen, Jr. "vision was to build an entertainment facility that would bring black and white Atlantans together", "cradled as it was between the commercial business community and the black neighborhood of Summerhill."[3] Other sources note that the original 1940s plan was to route the Downtown Connector freeway on the west side of downtown; the later plan to route it east of downtown was an effort to remove low-income black neighborhood and provide a buffer between the central business district and what remained of the black Summerhill, Mechanicsville and Peoplestown neighborhoods.[4]

The remaining eastern side of Washington–Rawson neighborhood was demolished in the early 1960s to make room for Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium and its parking lots.[5][6] Today, the area is part of the neighborhood of Summerhill.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ Atlanta and Environs By Franklin M. Garrett, p.930

- ^ "Life on Wessyngton Road: The History of Atlanta (Part 2): Other People". December 15, 2013.

- ^ '"Atlanta's Shovel", Public Broadcasting Atlanta

- ^ Rebuilding urban neighborhoods: achievements, opportunities, and limits by William Dennis Keating, Norman Krumholz

- ^ "Editor's Letter: Reclaiming a lost community". December 5, 2013.

- ^ "Rawson-Washington Urban Renewal records" (PDF). Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ^ "Atlanta Intown: Rediscovering Summerhill". July 2021.