Value chain

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2023) |

| Part of a series on |

| Strategy |

|---|

|

A value chain is a progression of activities that a business or firm performs in order to deliver goods and services of value to an end customer. The concept comes from the field of business management and was first described by Michael Porter in his 1985 best-seller, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance.[1]

The idea of [Porter's Value Chain] is based on the process view of organizations, the idea of seeing a manufacturing (or service) organization as a system, made up of subsystems each with inputs, transformation processes and outputs. Inputs, transformation processes, and outputs involve the acquisition and consumption of resources – money, labour, materials, equipment, buildings, land, administration and management. How value chain activities are carried out determines costs and affects profits.

— Institute for Manufacturing (IfM), Cambridge.[2]

According to the OECD Secretary-General (Gurría 2012),[3] the emergence of global value chains (GVCs) in the late 1990s provided a catalyst for accelerated change in the landscape of international investment and trade, with major, far-reaching consequences on governments as well as enterprises (Gurría 2012).[3]

Role of the business unit

[edit]According to Porter, the appropriate level for constructing a value chain is the business unit within a business,[4] not a business division or the company as a whole. Porter is concerned that analysis at the higher company levels may hide certain sources of competitive advantage only visible at the business unit level.[5]

Products pass through a chain of activities in order, and at each activity the product gains some value. The chain of activities gives the products more added value than the sum of added values of all activities.[4]

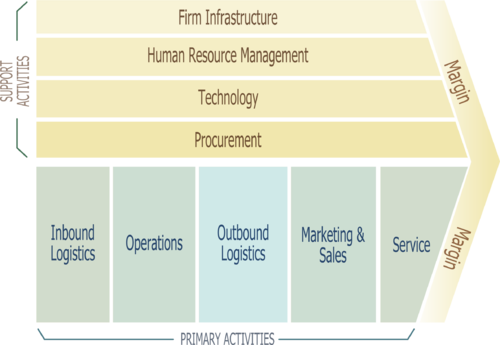

Primary activities

[edit]All five primary activities are essential in adding value and creating a competitive advantage and they are:[6][1]

- Inbound logistics: arranging the inbound movement of materials, parts, and/or finished inventory from suppliers to manufacturing or assembly plants, warehouses, or retail stores

- Operations: concerned with managing the process that converts inputs (in the forms of raw materials, labor, and energy) into outputs (in the form of goods and/or services).

- Outbound logistics: is the process related to the storage and movement of the final product and the related information flows from the end of the production line to the end user

- Marketing and sales: selling products and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large.

- Service: includes all the activities required to keep the product working effectively for the buyer after it is sold and delivered.

Companies can harness a competitive advantage at any one of the five activities in the value chain. For example, by creating outbound logistics that are highly efficient or by reducing a company's shipping costs, it allows to either realize more profits or pass the savings to the consumer by way of lower prices.[7]

Support activities

[edit]Using support activities helps make primary activities more effective. Increasing any of the four support activities helps at least one primary activity to work more efficiently.

- Infrastructure: consists of activities such as accounting, legal, finance, control, public relations, quality assurance and general (strategic) management.

- Technological development: pertains to the equipment, hardware, software, procedures and technical knowledge brought to bear in the firm's transformation of inputs(Raw materials) into outputs (finished goods).

- Human resources management: consists of all activities involved in recruiting, hiring, training, developing, compensating and (if necessary) dismissing or laying off personnel.

- Procurement: the acquisition of goods, services or works from an outside external source. In this field company also makes decisions of purchases.

Virtual value chain

[edit]The virtual value chain, created by John Sviokla and Jeffrey Rayport,[8] is a business model describing the dissemination of value-generating information services throughout an Extended Enterprise. This value chain begins with the content supplied by the provider, which is then distributed and supported by the information infrastructure; thereupon the context provider supplies actual customer interaction. It supports the physical value chain of procurement, manufacturing, distribution and sales of traditional companies.

Industry-level

[edit]An industry value-chain is a physical representation of the various processes involved in producing goods (and services), starting with raw materials and ending with the delivered product (also known as the supply chain). It is based on the notion of value-added at the link (read: stage of production) level. The sum total of link-level value-added yields total value. The French Physiocrats' Tableau économique is one of the earliest examples of a value chain. Wassily Leontief's input-output tables, published in the 1950s, provide estimates of the relative importance of each individual link in industry-level value-chains for the U.S. economy.

Global value chains

[edit]Cross border / cross region value chains

[edit]Often multinational enterprises (MNEs) developed global value chains, investing abroad and establishing affiliates that provided critical support to remaining activities at home. To enhance efficiency and to optimize profits, multinational enterprises locate "research, development, design, assembly, production of parts, marketing and branding" activities in different countries around the globe. MNEs offshore labour-intensive activities to China and Mexico, for example, where the cost of labor is the lowest (Gurría 2012).[3] The emergence of global value chains (GVCs) in the late 1990s provided a catalyst for accelerated change in the landscape of international investment and trade, with major, far-reaching consequences on governments as well as enterprises.(Gurría 2012)[3]

Global value chains in development

[edit]Through global value chains, there has been a growth in interconnectedness as MNEs play an increasingly larger role in the internationalisation of business. In response, governments have cut corporate income tax rates or introduced new incentives for research and development to compete in this changing geopolitical landscape (LeBlanc, Matthews & Mellbye 2013, p. 6).[9]

In an (industrial) development context, the concepts of global value chain analysis were first introduced in the 1990s (Gereffi et al.)[10] and have gradually been integrated into development policy by the World Bank, Unctad,[11] the OECD and others.

Value chain analysis has also been employed in the development sector as a means of identifying poverty reduction strategies by upgrading along the value chain.[12] Although commonly associated with export-oriented trade, development practitioners have begun to highlight the importance of developing national and intra-regional chains in addition to international ones.[13]

For example, the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) has investigated strengthening the value chain for sweet sorghum as a biofuel crop in India. Its aim in doing so was to provide a sustainable means of making ethanol that would increase the incomes of the rural poor, without sacrificing food and fodder security, while protecting the environment.[14]

Significance

[edit]The value chain framework quickly made its way to the forefront of management thought as a powerful analysis tool for strategic planning. The simpler concept of value stream mapping, a cross-functional process which was developed over the next decade,[15] had some success in the early 1990s.[16]

The value-chain concept has been extended beyond individual firms. It can apply to whole supply chains and distribution networks. The delivery of a mix of products (goods and services) to the end customer will mobilize different economic factors, each managing its own value chain. The industry wide synchronized interactions of those local value chains create an extended value chain, sometimes global in extent. Porter terms this larger interconnected system of value chains the "value system". A value system includes the value chains of a firm's supplier (and their suppliers all the way back), the firm itself, the firm distribution channels, and the firm's buyers (and presumably extended to the buyers of their products, and so on).

Capturing the value generated along the chain is the new approach taken by many management strategists. For example, a manufacturer might require its parts suppliers to be located nearby its assembly plant to minimize the cost of transportation. By exploiting the upstream and downstream information flowing along the value chain, the firms may try to bypass the intermediaries creating new business models, or in other ways create improvements in its value system.

SCOR

[edit]The Supply-Chain Council, a global trade consortium in operation with over 700 member companies, governmental, academic, and consulting groups participating in the last 10 years, manages the Supply-Chain Operations Reference (SCOR), the de facto universal reference model for Supply Chain including Planning, Procurement, Manufacturing, Order Management, Logistics, Returns, and Retail; Product and Service Design including Design Planning, Research, Prototyping, Integration, Launch and Revision, and Sales including CRM, Service Support, Sales, and Contract Management which are congruent to the Porter framework. The SCOR framework has been adopted by hundreds of companies as well as national entities as a standard for business excellence, and the U.S. Department of Defense has adopted the newly launched Design-Chain Operations Reference (DCOR) framework for product design as a standard to use for managing their development processes. In addition to process elements, these reference frameworks also maintain a vast database of standard process metrics aligned to the Porter model, as well as a large and constantly researched database of prescriptive universal best practices for process execution.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Porter, Michael E. (1985). Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. New York.: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781416595847. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ^ "Decision Support Tools: Porter's Value Chain". Cambridge University: Institute for Manufacturing (IfM). Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ^ a b c d Angel Gurría (5 November 2012). The Emergence of Global Value Chains: What Do They Mean for Business. G20 Trade and Investment Promotion Summit. Mexico City: OECD. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ a b Michael E. Porter (1985) Competitive advantage: creating and sustaining superior performance. The Free Press

- ^ Porter, M., The Value Chain and Competitive Advantage, in Barnes, D., ed (2001), Understanding Business: Processes, pg. 52, accessed 14 February 2024

- ^ Zamora, Elvira A. (2016-08-31). "Value Chain Analysis: A Brief Review". Asian Journal of Innovation and Policy. 5 (2): 116–128. doi:10.7545/ajip.2016.5.2.116. ISSN 2287-1608.

- ^ Kenton, Will. "Value Chain". Investopedia. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- ^ Rayport, J. F., & Sviokla, J. J. (2000), Exploiting the virtual value chain. HBR, 1995(november-december), 75-85

- ^ Pierre LeBlanc; Stephen Matthews; Kirsti Mellbye (4 September 2013). The Tax Policy Landscape Five Years after the Crisis (Report). OECD Taxation Working Papers. France: OECD. Archived from the original on 18 March 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ Gereffi, G., (1994). The Organisation of Buyer-Driven Global Commodity Chains: How US Retailers Shape Overseas Production Networks. In G. Gereffi, and M. Korzeniewicz (Eds), Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- ^ "Global Value Chains and Development" (PDF). Unctad. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-08-24.

- ^ Jonathan Mitchell; Christopher Coles & Jodie Keane (December 2009). "Upgrading Along Value Chains: Strategies for Poverty Reduction in Latin America" (PDF). Comercio y Pobreza en Latino América (COPLA). Briefing Paper. London: Overseas Development Institute.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Value Chain Development Wiki". Archived from the original on 2020-10-30.] Washington, D.C.: USAID.

- ^ Developing a sweet sorghum ethanol value chain Archived 2014-02-23 at the Wayback Machine ICRISAT, 2013

- ^ Martin, James (1995). The Great Transition: Using the Seven Disciplines of Enterprise Engineering. New York: AMACOM. ISBN 978-0-8144-0315-0., particularly the Con Edison example.

- ^ "The Horizontal Corporation". Business Week. 1993-12-20.

Further reading

[edit]- Kaplinsky, Raphael; Morris, Mike (2001). A handbook for value chain research. Brighton, England: Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex. OCLC 156818293. Archived from the original on 2021-04-11. Retrieved 2016-04-12. Pdf. (Prepared for the International Development Research Centre.)

External links

[edit] Media related to Value chain diagrams at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Value chain diagrams at Wikimedia Commons- Using a Value Chain Analysis in Project Management