Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria

| Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria | |

|---|---|

| Opera by Claudio Monteverdi | |

Title page of the libretto, published in 1641 | |

| Librettist | Giacomo Badoaro |

| Language | Italian |

| Based on | Homer's Odyssey |

| Premiere | |

Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria (SV 325, The Return of Ulysses to his Homeland) is an opera consisting of a prologue and five acts (later revised to three), set by Claudio Monteverdi to a libretto by Giacomo Badoaro. The opera was first performed at the Teatro Santi Giovanni e Paolo in Venice during the 1639–1640 carnival season. The story, taken from the second half of Homer's Odyssey,[n 1] tells how constancy and virtue are ultimately rewarded, treachery and deception overcome. After his long journey home from the Trojan Wars Ulisse, king of Ithaca, finally returns to his kingdom where he finds that a trio of villainous suitors are importuning his faithful queen, Penelope. With the assistance of the gods, his son Telemaco and a staunch friend Eumete, Ulisse vanquishes the suitors and recovers his kingdom.

Il ritorno is the first of three full-length works which Monteverdi wrote for the burgeoning Venetian opera industry during the last five years of his life. After its initial successful run in Venice the opera was performed in Bologna before returning to Venice for the 1640–41 season. Thereafter, except for a possible performance at the Imperial court in Vienna late in the 17th century, there were no further revivals until the 20th century. The music became known in modern times through the 19th-century discovery of an incomplete manuscript score which in many respects is inconsistent with the surviving versions of the libretto. After its publication in 1922 the score's authenticity was widely questioned, and performances of the opera remained rare during the next 30 years. By the 1950s the work was generally accepted as Monteverdi's, and after revivals in Vienna and Glyndebourne in the early 1970s it became increasingly popular. It has since been performed in opera houses all over the world, and has been recorded many times.

Together with Monteverdi's other Venetian stage works, Il ritorno is classified as one of the first modern operas. Its music, while showing the influence of earlier works, also demonstrates Monteverdi's development as a composer of opera, through his use of fashionable forms such as arioso, duet and ensemble alongside the older-style recitative. By using a variety of musical styles, Monteverdi is able to express the feelings and emotions of a great range of characters, divine and human, through their music. Il ritorno has been described as an "ugly duckling", and conversely as the most tender and moving of Monteverdi's surviving operas, one which although it might disappoint initially, will on subsequent hearings reveal a vocal style of extraordinary eloquence.

Historical context

[edit]Monteverdi was an established court composer in the service of Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga in Mantua when he wrote his first operas, L'Orfeo and L'Arianna, in the years 1606–08.[1] After falling out with Vincenzo's successor, Duke Francesco Gonzaga, Monteverdi moved to Venice in 1613 and became director of music at St Mark's Basilica, a position he held for the rest of his life.[2] Alongside his steady output of madrigals and church music, Monteverdi continued to compose works for the stage, though not actual operas. He wrote several ballets and, for the Venice carnival of 1624–25, Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda ("The Battle of Tancred and Clorinda"), a hybrid work with some characteristics of ballet, opera and oratorio.[3][n 2]

In 1637 fully-fledged opera came to Venice with the opening of the Teatro San Cassiano. Sponsored by the wealthy Tron family, this theatre was the first in the world specifically devoted to opera.[5] The theatre's inaugural performance, on 6 March 1637, was L'Andromeda by Francesco Manelli and Benedetto Ferrari. This work was received with great enthusiasm, as was the same pair's La Maga fulminata the following year. In rapid succession three more opera houses opened in the city, as the ruling families of the Republic sought to express their wealth and status by investing in the new musical fashion.[5] At first, Monteverdi remained aloof from these activities, perhaps on account of his age (he was over 70), or perhaps through the dignity of his office as maestro di capella at St. Mark's. Nevertheless, an unidentified contemporary, commenting on Monteverdi's silence, opined that the maestro might yet produce an opera for Venice: "God willing, one of these nights he too will step onto the stage."[6] This remark proved prescient; Monteverdi's first public contribution to Venetian opera came in the 1639–40 carnival season, a revival of his L'Arianna at the Teatro San Moisè.[7][n 3]

L'Arianna was followed in rapid succession by three brand new Monteverdi operas, of which Il ritorno was the first.[9] The second, Le nozze d’Enea con Lavinia ("The Marriage of Aeneas to Lavinia"), was performed during the 1640–41 carnival; Monteverdi's music is lost, but a copy of the libretto, of unknown authorship, survives. The last of the three, written for the 1642–43 carnival, was L'incoronazione di Poppea ("The Coronation of Poppea"), performed shortly before the composer's death in 1643.[7][10]

Creation

[edit]Libretto

[edit]

Giacomo Badoaro (1602–1654) was a prolific poet in the Venetian dialect who was a member of the Accademia degli Incogniti, a group of free-thinking intellectuals interested in promoting musical theatre in Venice—Badoaro himself held a financial interest in the Teatro Novissimo.[11] Il ritorno was his first libretto; he would later, in 1644, write another Ulysses-based libretto for Francesco Sacrati.[11] The text of Il ritorno, originally written in five acts but later reorganised as three, is a generally faithful adaptation of Homer's Odyssey, Books 13–23, with some characterisations altered or expanded. Badoaro may have been influenced in his treatment of the story by the 1591 play Penelope by Giambattista della Porta.[12] The libretto was written with the express purpose of tempting Monteverdi to enter the world of Venetian opera, and it evidently captured the elderly composer's imagination.[12][13] Badoaro and Monteverdi used a classical story to illustrate the human condition of their own times.[14]

The Monteverdi scholar Ellen Rosand has identified 12 versions of the published libretto that have been discovered in the years since the first performance.[15] Most of these appear to be 18th-century copies, possibly from a single source; some are literary versions, unrelated to any theatrical performances. All but one of the 12 identify Badoaro as the author, while the other gives no name. Only two refer to Monteverdi as the composer, though this is not significant—composers' names were rarely given on printed librettos. The texts are all generally the same in each case, and all differ from the one surviving copy of Monteverdi's musical score, which has three acts instead of five, a different prologue, a different ending, and many scenes and passages either omitted or rearranged.[15][16] Some of the libretto copies locate the opera's first performance at Teatro San Cassiano, although Teatro SS Giovanni e Paolo is now generally accepted as the opening venue.[17]

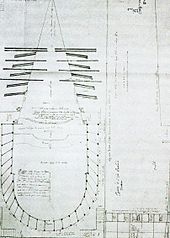

Composition

[edit]It is not known when Monteverdi received the libretto from Badoaro, but this was presumably during or before 1639 since the work was being prepared for performance in the 1639–40 carnival. In keeping with the general character of Venetian opera, the work was written for a small band—around five string players and various continuo instruments. This reflected the financial motives of the merchant princes who were sponsoring the opera houses—they demanded commercial as well as artistic success, and wanted to minimise costs.[7] As was common at the time, precise instrumentation is not indicated in the score, which exists in a single handwritten manuscript discovered in the Vienna National Library in the 19th century.[12][n 4]

A study of the score reveals many characteristic Monteverdi features, derived from his long experience as a composer for the stage and of other works for the human voice. Rosand believes that rather than casting doubts on Monteverdi's authorship, the significant differences between the score and the libretto might lend support to it, since Monteverdi was well known for his adaptations of the texts presented to him.[13] Ringer reinforces this, writing that "Monteverdi boldly reshaped Badoaro's writing into a coherent and supremely effective foundation for a music drama", adding that Badoaro claimed that he could no longer recognise the work as his own.[9] Contemporaries of the composer and the librettist saw an identification between Ulysses and Monteverdi; both are returning home—"home" in Monteverdi's case being the medium of opera which he had mastered and then left, 30 years earlier.[19]

Authenticity

[edit]Before and after the publication of the score in 1922, scholars questioned the work's authenticity, and its attribution to Monteverdi continued to be in some doubt until the 1950s. The Italian musicologist Giacomo Benvenuti maintained, on the basis of a 1942 performance in Milan, that the work was simply not good enough to be by Monteverdi.[20] Apart from the stylistic differences between Il ritorno and Monteverdi's other surviving late opera, L'incoronazione di Poppea, the main issue which raised doubts was the series of discrepancies between the score and the libretto.[13] However, much of the uncertainty concerning the attribution was resolved through the discovery of contemporary documents, all confirming Monteverdi's role as the composer. These documents include a letter from the unknown librettist of Le nozze d'Enea in Lavinia, which discusses Monteverdi's setting of Il ritorno.[21] There is also Badoaro's preface to the Il ritorno libretto, addressed to the composer, which includes the wording "I can firmly state that my Ulysses is more indebted to you than ever was the real Ulysses to the ever-gracious Minerva".[22] A 1644 letter from Badoaro to Michelangelo Torcigliani contains the statement "Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria was embellished with the music of Claudio Monteverdi, a man of great fame and enduring name".[22] Finally, a 1640 booklet entitled Le Glorie della Musica indicates the Badoaro-Monteverdi pairing as the creators of the opera.[23] In the view of conductor and instrumentalist Sergio Vartolo, these findings establish Monteverdi as the principal composer "beyond a shadow of a doubt".[24] Although parts of the music may be by other hands, there is no doubt that the work is substantially Monteverdi's and remains close to his original conception.[25]

Roles

[edit]The work is written for a large cast—thirty roles including small choruses of heavenly beings, sirens and Phaecians—but these parts can be organised among fourteen singers (three sopranos, two mezzo-sopranos, one alto, six tenors and two basses) by appropriate doubling of roles. This approximates to the normal forces employed in Venetian opera. In the score, the role of Eumete changes midway through Act II from tenor to soprano castrato, suggesting that the surviving manuscript may have been created from more than one source. In modern performances the latter part of Eumete's role is usually transposed to a lower range, to accommodate the tenor voice throughout.[26]

| Role | Voice type | Appearances | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| L'humana Fragilità (Human Frailty) | mezzo-soprano | Prologue | |

| Il Tempo (Time) god | bass | Prologue | |

| La Fortuna (Fortune) goddess | soprano | Prologue | |

| L'Amore (Cupid) god | soprano | Prologue | The role may initially have been played by a boy soprano, possibly Costantino Manelli[27] |

| Penelope Wife to Ulisse | mezzo-soprano | Act 1: I, X Act 2: V, VII, XI, XII Act 3: III, IV, V, IX, X |

The role was initially sung, in Venice and Bologna, by Giulia Paolelli[27] |

| Ericlea (Eurycleia) Penelope's nurse | mezzo-soprano | Act 1: I Act 3: VIII, X |

|

| Melanto (Melantho) attendant to Penelope | soprano | Act 1: II, X Act 2: IV Act 3: III |

|

| Eurimaco (Eurymachus) a servant to Penelope's suitors | tenor | Act 1: II Act 2: IV, VIII |

|

| Nettuno (Neptune) sea-god | bass | Act 1: V, VI Act 3: VII |

The role was probably sung, in Venice and Bologna, by the impresario Francesco Manelli[27] |

| Giove (Jupiter) supreme god | tenor | Act 1: V Act 3: VII |

A renowned Venetian tenor, Giovan Battista Marinoni, may have appeared in the initial Venice run as Giove.[26] |

| Coro Feaci (Chorus of Phaeacians) | alto, tenor, bass | Act 1: VI | |

| Ulisse (Ulysses or Odysseus) King of Ithaca |

tenor | Act 1: VII, VIII, IX, XIII Act 2: II, III, IX, X, XII Act 3: X |

|

| Minerva goddess | soprano | Act 1: VIII, IX Act 2: I, IX, XII Act 3: VI, VII |

The role was initially sung, in Venice and Bologna, by Maddalena Manelli, wife of Francesco.[27] |

| Eumete (Eumetes) a shepherd | tenor | Act 1: XI, XII, XIII Act 2: II, VII, X, XII Act 3: IV, V, IX |

|

| Iro (Irus) a parasite | tenor | Act 1: XII Act 2: XII Act 3: I |

|

| Telemaco (Telemachus) son of Ulisse | tenor | Act 2: I, II, III, XI Act 3: V, IX, X |

|

| Antinoo (Antinous) suitor to Penelope | bass | Act 2: V, VIII, XII | |

| Pisandro (Peisander) suitor to Penelope | tenor | Act 2: V, VIII, XII | |

| Anfinomo (Amphinomus) suitor to Penelope | alto or countertenor | Act 2: V, VIII, XII | |

| Giunone (Juno) goddess | soprano | Act 3: VI, VII | |

| Coro in Cielo (Heavenly chorus) | soprano, alto, tenor | Act 3: VII | |

| Coro marittimo (Chorus of sirens) | soprano, tenor, bass | Act 3: VII |

Synopsis

[edit]The action takes place on and around the island of Ithaca, ten years after the Trojan Wars. English translations used in the synopsis are from Geoffrey Dunn's version, based on Raymond Leppard's 1971 edition,[28] and from Hugh Ward-Perkins's interpretation issued with Sergio Vartolo's 2006 recording for Brilliant Classics.[29] Footnotes provide the original Italian.

Prologue

[edit]The spirit of human frailty (l'humana Fragilità) is mocked in turn by the gods of time (il Tempo), fortune (la Fortuna) and love (l'Amore). Man, they claim, is subject to their whims: "From Time, ever fleeting, from Fortune's caresses, from Love and its arrows...No mercy from me!"[n 5] They will render man "weak, wretched, and bewildered."[n 6]

Act 1

[edit]

In the palace at Ithaca, Penelope mourns the long absence of Ulysses: "The awaited one does not return, and the years pass by."[n 7] Her grief is echoed by her nurse, Ericlea. As Penelope leaves, her attendant Melanto enters with Eurimaco, a servant to Penelope's importunate suitors. The two sing passionately of their love for each other ("You are my sweet life").[n 8] The scene changes to the Ithacan coast, where the sleeping Ulisse is brought ashore by the Phaecians (Faeci), whose action is in defiance of the wishes of gods Giove and Nettuno. The Phaecians are punished by the gods who turn them and their ship to stone. Ulysses awakes, cursing the Phaecians for abandoning him: "To your sails, falsest Phaeacians, may Boreas be ever hostile!"[n 9] From the goddess Minerva, who appears disguised as a shepherd boy, Ulisse learns that he is in Ithaca, and is told of "the unchanging constancy of the chaste Penelope",[n 10] in the face of the persistent importunings of her evil suitors. Minerva promises to lead Ulisse back to the throne if he follows her advice; she tells him to disguise himself so that he can penetrate the court secretly. Ulisse goes to seek out his loyal servant Eumete, while Minerva departs to search for Telemaco, Ulisse's son who will help his father reclaim the kingdom. Back at the palace, Melanto tries vainly to persuade Penelope to choose one of the suitors: "Why do you disdain the love of living suitors, expecting comfort from the ashes of the dead?"[n 11] In a wooded grove Eumete, banished from court by the suitors, revels in the pastoral life, despite the mockery of Iro, the suitors' parasitic follower, who sneers: "I live among kings, you here among the herds."[n 12] After Iro is chased away, Ulisse enters disguised as a beggar, and assures Eumete that his master the king is alive, and will return. Eumete is overjoyed: "My long sorrow will fall, vanquished by you."[n 13]

Act 2

[edit]

Minerva and Telemaco return to Ithaca in a chariot. Telemaco is greeted joyfully by Eumete and the disguised Ulisse in the woodland grove: "O great son of Ulysses, you have indeed returned!"[n 14] After Eumete goes to inform Penelope of Telemaco's arrival a bolt of fire descends on Ulisse, removing his disguise and revealing his true identity to his son. The two celebrate their reunion before Ulisse sends Telemaco to the palace, promising to follow shortly. In the palace, Melanto complains to Eurimaco that Penelope still refuses to choose a suitor: "In short, Eurymachus, the lady has a heart of stone."[n 15] Soon afterwards Penelope receives the three suitors (Antinoo, Pisandro, Anfinomo), and rejects each in turn despite their efforts to enliven the court with singing and dancing: "Now to enjoyment, to dance and song!"[n 16] After the suitors' departure Eumete tells Penelope that Telemaco has arrived in Ithaca, but she is doubtful: "Such uncertain things redouble my grief."[n 17] Eumete's message is overheard by the suitors, who plot to kill Telemaco. However, they are unnerved when a symbolic eagle flies overhead, so they abandon their plan and renew their efforts to capture Penelope's heart, this time with gold. Back in the woodland grove, Minerva tells Ulisse that she has organised a means whereby he will be able to challenge and destroy the suitors. Resuming his beggar's disguise, Ulisse arrives at the palace, where he is challenged to a fight by Iro, ("I will pluck out the hairs of your beard one by one!"[n 18]), a challenge he accepts and wins. Penelope now states that she will accept the suitor who is able to string Ulisse's bow. All three suitors attempt the task unsuccessfully. The disguised Ulisse then asks to try though renouncing the prize of Penelope's hand, and to everyone's amazement he succeeds. He then angrily denounces the suitors and, summoning the names of the gods, kills all three with the bow: "This is how the bow wounds! To death, to havoc, to ruin!"[n 19]

Act 3

[edit]Deprived of the suitors' patronage, Iro commits suicide after a doleful monologue ("O grief, O torment that saddens the soul!"[n 20]) Melanto, whose lover Eurimaco was killed with the suitors, tries to warn Penelope of the new danger represented by the unidentified slayer, but Penelope is unmoved and continues to mourn for Ulisse. Eumete and Telemaco now inform her that the beggar was Ulisse in disguise, but she refuses to believe them: "Your news is persistent and your comfort hurtful."[n 21] The scene briefly transfers to the heavens, where Giunone, having been solicited by Minerva, persuades Giove and Nettune that Ulisse should be restored to his throne. Back in the palace the nurse Ericlea has discovered Ulisse's identity by recognising a scar on his back, but does not immediately reveal this information: "Sometimes the best thing is a wise silence."[n 22] Penelope continues to disbelieve, even when Ulisse appears in his true form and when Ericlea reveals her knowledge of the scar. Finally, after Ulisse describes the pattern of Penelope's private bedlinen, knowledge that only he could possess, she is convinced. Reunited, the pair sing rapturously to celebrate their love: "My sun, long sighed for! My light, renewed!"[n 23]

Reception and performance history

[edit]Early performances

[edit]Il ritorno was first staged during the 1639–40 Venice carnival by the theatrical company of Manelli and Ferrari, who had first brought opera to Venice. The date of the Il ritorno première is not recorded.

According to Carter the work was performed at least ten times during its first season; it was then taken by Manelli to Bologna, and played at the Teatro Castrovillani before returning to Venice for the 1640–41 carnival season.[13][30] From markings in the extant score, it is likely that the first Venice performances were in five acts, the three-act form being introduced either in Bologna or in the second Venice season.[31] A theory offered by Italian opera historian Nino Pirrotta that the Bologna performance was the work's première is not supported by subsequent research.[8] The opera's revival in Venice only one season after its première was very unusual, almost unique in the 17th century, and testifies to the opera's popular success—Ringer calls it "one of the most successful operas of the century".[7] Carter offers a reason for its appeal to the public: "The opera has enough sex, gore and elements of the supernatural to satisfy the most jaded Venetian palate."[32]

The venue for Il ritorno's première was at one time thought to be the Teatro Cassiano, but scholarly consensus considers it most likely that both the 1639–40 and 1640–41 performances were at the Teatro SS Giovanni e Paolo. This view is supported by a study of the performance schedules for other Venice operas, and by the knowledge that the Manelli company had severed its connection with the Teatro Cassiano before the 1639–40 season.[33] The Teatro SS Giovanni e Paolo, owned by the Grimani family, would also be the venue for the premières of Monteverdi's Le nozze d'Enea and Poppea.[34] In terms of its staging Il ritorno is, says Carter, fairly undemanding, requiring three basic sets—a palace, a seascape and a woodland scene—which were more or less standard for early Venetian opera. It did, however, demand some spectacular special effects: the Phaecian ship turns to stone, an airborne chariot transports Minerva, a bolt of fire transforms Ulisse.[35]

After the Venice 1640–41 revival there is no record of further performances of Il ritorno in Venice, or elsewhere, before the discovery of the music manuscript in the 19th century. The discovery of this manuscript in Vienna suggests that at some time the opera was staged there, or at least contemplated, perhaps before the Imperial court.[18] The Monteverdi scholar Alan Curtis dates the manuscript's arrival in Vienna to 1675, during the reign of the Emperor Leopold I who was a considerable patron of the arts, and opera in particular.[31][36]

Modern revivals

[edit]

The Vienna manuscript score was published by Robert Haas in 1922.[37] Publication was followed by the first modern performance of the opera, in an edition by Vincent d'Indy, in Paris on 16 May 1925.[38] For the next half-century performances remained rare. The BBC introduced the opera to British listeners with a radio broadcast on 16 January 1928, again using the d'Indy edition.[38] The Italian composer Luigi Dallapiccola prepared his own edition, which was performed in Florence in 1942, and Ernst Krenek's version was shown in Wuppertal, Germany, in 1959.[13][38] The first British staging was a performance at St. Pancras Town Hall, London, on 16 March 1965, given with the English Chamber Orchestra conducted by Frederick Marshall.[39][40]

The opera entered a wider repertory in the early 1970s, with performances in Vienna (1971) and Glyndebourne (1972).[38] The Vienna performance used a new edition prepared by Nikolaus Harnoncourt, whose subsequent partnership with the French opera director Jean-Pierre Ponnelle led to the staging of the opera in many European cities. Ponnelle's 1978 presentation in Edinburgh was later described as "infamous";[41] at the time, critic Stanley Sadie praised the singers but criticised the production for its "frivolity and indeed coarseness".[42] In January 1974 Il ritorno received its United States première with a production mounted by the Opera Society of Washington at the Kennedy Center, on the basis of the Harnoncourt edition.[43][44] Led by conductor Alexander Gibson, the cast included Frederica von Stade as L'humana Fragilità and Penelope, Claude Corbeil as Il Tempo and Antinoo, Joyce Castle as La Fortuna, Barbara Hocher as Amore and Melanto, Richard Stilwell as Ulisse, Donald Gramm as Nettuno, William Neill as Giove, Carmen Balthrop as Minerva, David Lloyd as Eumete, R. G. Webb as Iro, Howard Hensel as Eurimaco, Paul Sperry as Telemaco, Dennis Striny as Pisandro, and John Lankston as Anfinomo.[43]

More recently the opera has been performed at the New York Lincoln Center by New York City Opera, and at other venues throughout the United States.[45] A 2006 Welsh National Opera production by David Alden, designed by Ian McNeil, featured neon signs, stuffed cats, a Neptune in flippers and a wet suit, Minerva in the form of the aviator Amelia Earhart, and Jupiter as a small-time hustler, an interpretation defended by the critic Anna Picard – "the gods were always contemporary fantasies, while an abandoned wife and a humbled hero are eternals."[46]

The German composer Hans Werner Henze was responsible for the first two-act version, which was produced at the Salzburg Festival on 11 August 1985, with divided critical reaction.[47] Two-act productions have since become increasingly common.[9] The South African artist and animator William Kentridge devised a version of the opera based on the use of puppets and animated film, using around half of the music. This version was shown in Johannesburg in 1998 and then toured the world, appearing at the Lincoln Center in 2004 and at the Edinburgh Festival in 2009.[48][49]

Music

[edit]According to Denis Arnold, although Monteverdi's late operas retain elements of the earlier Renaissance intermezzo and pastoral forms, they may be fairly considered as the first modern operas.[50] In the 1960s, however, David Johnson found it necessary to warn prospective Il ritorno listeners that if they expected to hear opera akin to Verdi, Puccini or Mozart, they would be disappointed: "You have to submit yourself to a much slower pace, to a much more chaste conception of melody, to a vocal style that is at first or second hearing merely like dry declamation and only on repeated hearings begins to assume an extraordinary eloquence."[51] A few years later, Jeremy Noble in a Gramophone review wrote that Il ritorno was the least known and least performed of Monteverdi's operas, "quite frankly, because its music is not so consistently full of character and imagination as that of Orfeo or Poppea."[52] Arnold called the work an "ugly duckling".[53] Later analysts have been more positive; to Mark Ringer Il ritorno is "the most tender and moving of Monteverdi's operas",[54] while in Ellen Rosand's view the composer's ability to portray real human beings through music finds its fullest realisation here, and in Poppea a few years later.[13]

The music of Il ritorno shows the unmistakable influence of the composer's earlier works. Penelope's lament, which opens Act I, is reminiscent both of Orfeo's Redentemi il mio ben and the lament from L'Arianna. The martial-sounding music which accompanies references to battles and the killing of the suitors, derives from Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda, while for the song episodes in Il ritorno Monteverdi draws in part on the techniques which he developed in his 1632 vocal work Scherzi musicale.[55] In typical Monteverdi fashion the opera's characters are vividly portrayed in their music.[53] Penelope and Ulisse, with what is described by Ringer as "honest musical and verbal declamation", overcome the suitors whose styles are "exaggerated and ornamental".[54] Iro, perhaps "the first great comic character in opera",[56] opens his Act 3 monologue with a wail of distress that stretches across eight bars of music.[57] Penelope begins her lament with a reiteration of E flats that, according to Ringer, "suggest a sense of motionless and emotional stasis" that well represents her condition as the opera begins.[56] At the work's end, her travails over, she unites with Ulisse in a duet of life-affirming confidence which, Ringer suggests, no other composer bar Verdi could have achieved.[58]

Rosand divides the music of Il ritorno into "speech-like" and "musical" utterances. Speech, usually in the form of recitative, delivers information and moves the action forward, while musical utterances, either formal songs or occasional short outbursts, are lyrical passages that enhance an emotional or dramatic situation.[59] This division is, however, less formal than in Monteverdi's earlier L'Orfeo; in Il ritorno information is frequently conveyed through the use of arioso, or even aria at times, increasing both tunefulness and tonal unity.[25] As with Orfeo and Poppea, Monteverdi differentiates musically between humans and gods, with the latter singing music which is usually more profusely melodic—although in Il ritorno, most of the human characters have some opportunity for lyrical expression.[12] According to the reviewer Iain Fenlon, "it is Monteverdi's mellifluous and flexible recitative style, capable of easy movement between declamation and arioso, which remains in the memory as the dominant language of the work."[60] Monteverdi's ability to combine fashionable forms such as the chamber duet and ensembles with the older-style recitative from earlier in the century further illustrate the development of the composer's dramatic style.[47][50] Monteverdi's trademark feature of "stilo concitato" (rapid repetition of notes to suggest dramatic action or excitement) is deployed to good effect in the fight scene between Ulisse and Iro, and in the slaying of the suitors.[61][62] Arnold draws attention to the great range of characters in the opera—the divine, the noble, the servants, the evil, the foolish, the innocent and the good. For all of these "the music expresses their emotions with astonishing accuracy."[50]

List of musical items

[edit]The following is a list of the "scenes" into which the libretto is divided. Each separate scene is typically a mixture of musical elements: recitative, arioso, arietta and sometimes ensemble, with occasional instrumental interludes.

| Scene | Performed by | First lines[n 24] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prologue | |||

| Prologue | L'humana Fragilità, il Tempo, la Fortuna, l'Amore | Mortal cosa son io (I am mortal) |

In the libretto prologue the gods are Fato, Fortezza and Prudenza (Fate, Strength and Prudence)[31] |

| Act 1 | |||

| 1: Scene I | Penelope, Ericlea | Di misera regina non terminati mai dolenti affani! (Miserable Queen, sorrow and trouble never end!) |

|

| 1: Scene II | Melanto, Eurimaco | Duri e penosi son gli amorosi fieri desir (Bitter and hard are the lovers' cruel torments) |

|

| 1: Scene III | Maritime scene, music missing from score | ||

| 1: Scene IV | Music only | The sleeping Ulisse is placed ashore by the Faeci | |

| 1: Scene V | Nettuno, Giove | Superbo è l'huom (Man is proud) |

In some editions this scene begins with a Chorus of Sirens, using other music.[63] |

| 1: Scene VI | Chorus of Faeci, Nettuno | In questo basso mondo (In this base world) |

|

| 1: Scene VII | Ulisse | Dormo ancora o son desto? (Am I still asleep, or am I awake?) |

|

| 1: Scene VIII | Minerva, Ulisse | Cara e lieta gioventù (Dear joyful time of youth) |

|

| 1: Scene IX | Minerva, Ulisse | Tu d'Aretusa a fonte intanto vanne (Go thou meanwhile to the fountain of Arethusa) |

Act 1 in the five-act libretto ends here |

| 1: Scene X | Penelope, Melanto | Donata un giorno, o dei, contento a' desir miei (Grant me one day, ye gods, content to all my wishes) |

|

| 1: Scene XI | Eumete | Come, oh come mal si salva un regio amante (O how badly does a loving king save himself) |

|

| 1: Scene XII | Iro, Eumete | Pastor d'armenti può prati e boschi lodar (A keeper of cattle can praise meadows and woods) |

|

| 1: Scene XIII | Eumete, Ulisse | Ulisse generoso! Fu nobile intrapresa {Noble Ulysses! You undertook noble deeds) |

End of Act 1 (score) |

| Act 2 | |||

| 2: Scene I | Telemaco, Minerva | Lieto cammino, dolce viaggio (Happy journey, sweet voyage) |

|

| 2: Scene II | Eumete, Ulisse, Telemaco | Oh gran figlio d'Ulisse! È pur ver che tu torni O great son of Ulysses, is it true you have come back?) |

|

| 2: Scene III | Telemaco, Ulisse | Che veggio, ohimè, che miro? (What do I see, alas, what do I behold?) |

Act 2 in the five-act libretto ends here |

| 2: Scene IV | Melanto, Eurimaco | Eurimaco! La donna insomma haun cor di sasso (Eurymachus, in short the lady has a heart of stone) |

|

| 2: Scene V | Antinoo, Pisandro, Anfinomo, Penelope | Sono l'altre regine coronate di servi e tu d'amanti (Other queens are crowned by servants, you by lovers) |

|

| 2: Scene VI | "Ballet of the Moors", music missing from score | ||

| 2: Scene VII | Eumete, Penelope | Apportator d'altre novelle vengo! (I come as bearer of great tidings!) |

|

| 2: Scene VIII | Antinoo, Anfinomo, Pisandro, Eurimaco | Compagni, udiste? (Friends, did you hear?) |

|

| 2: Scene IX | Ulisse, Minerva | Perir non può chi tien per scorta il cielo (He who has heaven as an escort cannot perish) |

|

| 2: Scene X | Eumete, Ulisse | Io vidi, o pelegrin, de' Proci amanti (I saw, O wanderer, the amorous suitors) |

Act 3 in the five-act libretto ends here. In Henze's two-act version Act 1 ends here |

| 2: Scene XI | Telemaco, Penelope | Del mio lungo viaggio i torti errori già vi narrari (The tortuous ways of my long journey I have already recounted) |

|

| 2: Scene XII | Antinoo, Eumete, Iro, Ulisse, Telemaco, Penelope, Anfinomo, Pisandro | Sempre villano Eumete (Always a lout, Eumete...) |

Act 4 in the five-act libretto ends here |

| Act 3 | |||

3: Scene I |

Iro | O dolor, o martir che l'alma attrista (O grief, O torment that saddens the soul) |

|

| 3: Scene II | Scene not set to music because Monteverdi considered it "too melancholy".[57] The souls of the dead suitors are seen entering hell. | ||

| 3: Scene III | Melanto, Penelope | E quai nuovi rumori, (And what strange uproars) |

|

| 3: Scene IV | Eumete, Penelope | Forza d'occulto affetto raddolcisce il tuo petto (The power of a hidden affection may calm your breast) |

|

| 3: Scene V | Telemaco, Penelope | È saggio Eumete, è saggio! (Eumaeus is truly wise!) |

|

| 3: Scene VI | Minerva, Giunone | Fiamma e l'ira, o gran dea, foco è lo sdegno! (Anger is the flame, O great goddess, hatred is the fire) |

|

| 3: Scene VII | Giunone, Giove, Nettuno, Minerva, Heavenly Chorus, Chorus of Sirens | Gran Giove, alma de' dei, (Great Jove, soul of the gods) |

|

| 3: Scene VIII | Ericlea | Ericlea, che vuoi far? (Eurycleia, what will you do?) |

|

| 3: Scene IX | Penelope, Eumete, Telemaco | Ogni nostra ragion sen porta il vento (All your reason is borne away by the wind) |

|

| 3: Scene X | Ulisse, Penelope, Ericlea | O delle mie fatiche meta dolce e soave (O sweet, gentle ending of my troubles) |

|

| End of opera | |||

Recording history

[edit]The first recording of the opera was issued in 1964 by Vox, a version which incorporated substantial cuts.[20] The first complete recording was that of Harnoncourt and Concentus Musicus Wien in 1971.[64] Raymond Leppard's 1972 Glyndebourne version was recorded in a concert performance in the Royal Albert Hall; the following year the same Glyndebourne cast was recorded in a full stage performance. Leppard's third Glyndebourne version was issued in 1980, when the orchestration with strings and brass drew critical comment from Denis Arnold in his Gramophone review: "Too much of the music left with a simple basso continuo line in the original has been fully orchestrated with strings and brass, with the result that the expressive movement between recitative, arioso and aria is obscured." (For further details, see Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria (Raymond Leppard recording).) Much the same criticism, says Arnold, may be levelled at Harnoncourt's 1971 recording.[65]

Among more recent issues is the much praised 1992 René Jacobs performance with Concerto Vocale, "a recording that all serious Monteverdians will wish to return to frequently", according to Fenlon.[60] Jacobs's version is in the original five-act form, and uses music by Luigi Rossi and Giulio Caccini for some choruses which appear in the libretto but which are missing from Monteverdi's score.[66] More than thirty years after his first issue, Harnoncourt's 2002 version, with Zurich Opera, was recorded live in DVD format. While the quality of the vocal contributions were praised, Harnoncourt's "big-band score" and bold instrumentation were highlighted by Gramophone critic Jonathan Freeman-Attwood as a likely source of future debate.[67]

Editions

[edit]Since the publication of the Vienna manuscript score in 1922 the opera has been edited frequently, sometimes for specific performances or recordings. The following are the main published editions of the work, to 2010.

- Robert Haas (Vienna, 1922 in the series Denkmäler der Tonkunst in Österreich)[68]

- Vincent d'Indy (Paris, 1926)[13]

- Gian Francesco Malipiero (Vienna, 1930 in Claudio Monteverdi: Tutte le opere)[13]

- Luigi Dallapiccola (Milan, 1942)[69]

- Ernst Krenek (Wuppertal, 1959)[38]

- Nikolaus Harnoncourt (Vienna, 1971)[38]

- Raymond Leppard (London, 1972)[13]

- Hans Werner Henze (Salzburg, 1985)[69]

- Alan Curtis (London, 2002)[31]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Ulysses" is the Latin form of the Greek "Odysseus", hero of the Odyssey

- ^ Monteverdi scholar Tim Carter draws attention to the difficulties in allocating Il combattimento to a specific genre—neither secular oratorio, nor opera, nor ballet, but with some features from all these. "Several authors can say what it is not .... But no one can say quite what it is."[4]

- ^ An indication of Monteverdi's status at the time is revealed by the dedication in a reprinted libretto for L'Arianna. Monteverdi is described as "most celebrated Apollo of the century and the highest intelligence of the heavens of humanity."[8]

- ^ Ringer credits the discovery to the Austrian composer and historian August Wilhelm Ambros, in 1881. However, if Ambros made the discovery, the year must have been earlier, as he died in 1876.[18]

- ^ Il Tempo ch'affretta, Fortuna ch'alletta, Amor che saetta...Pietate non ha!

- ^ Fragile, misero, torbido quest'uom sarà

- ^ L'aspettato non giunge, e pur fuggotto gli anni (1.I)

- ^ Dolce mia vita, mia vita sei! (1.II)

- ^ Falsissimi Faeci, sempre Borea nemico (1.VII)

- ^ Di Penelope casta l'immutabil costanza (1.VIII)

- ^ A che sprezzi gli ardort de' viventi amatori per attener conforti Dal cenere de' morti? (1.X)

- ^ Colà tra regi io sto, tu fra gli armenti qui (1.XII)

- ^ Il mio lungo cordoglio da te vinto cadrà (1.XIII)

- ^ O gran figlio d'Ulisse, è pur ver che tu torni (2.II)

- ^ Eurimaco, la donna insomma ha un cor di sasso (2.IV)

- ^ All'allegrezze dunque, al ballo, al canto! (2.V)

- ^ Per si dubbie novelle o s'addopia il mio male. (2.VII)

- ^ E che sì che ti strappo i peli della barba ad uno ad ono! (2.XII)

- ^ Così l'arco ferisce! Alle morti, alle stragi, alle ruine! (2.XII)

- ^ O dolor, O martir, che l'alma attrista! (3.I)

- ^ Relatore importuno, consolator nocivo! (3.IV)

- ^ Bella cosa tavolta è un bel tacer (3.VIII)

- ^ Sospirato mio sole! Rinnovata mia luce! (3.X)

- ^ Translations based on Geoffrey Dunn and Hugh Ward-Perkins

Citations

[edit]- ^ Carter 2002, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Neef 2000, p. 324.

- ^ Carter, Tim (2007). "Monteverdi, Claudio: Venice". In Macy, Laura (ed.). Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ Carter 2002, pp. 172–73.

- ^ a b Ringer 2006, pp. 130–31.

- ^ Rosand 1991, pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b c d Ringer 2006, pp. 135–36.

- ^ a b Rosand 1991, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Ringer 2006, pp. 137–38.

- ^ Carter 2002, p. 305.

- ^ a b Walker, Thomas. "Badoaro, Giacomo". In Macy, Laura (ed.). Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ a b c d Ringer 2006, pp. 140–41.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Rosand, Ellen (2007). "Ritorno d'Ulisse in patria". In Macy, Laura (ed.). Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ Ringer 2006, p. 145.

- ^ a b Rosand 2007b, pp. 52–56.

- ^ Rosand 1991, p. 53.

- ^ Rosand 2007b, pp. 57–58.

- ^ a b Ringer 2006, p. 139.

- ^ Ringer 2006, p. 142.

- ^ a b "Monteverdi: Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria – complete". The Gramophone. Haymarket. September 1971. p. 100. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ^ Rosand & Vartolo, pp. 21–23.

- ^ a b Rosand & Vartolo, p. 24

- ^ Rosand & Vartolo, p. 25.

- ^ Rosand & Vartolo, p. 20.

- ^ a b Chew, Geoffrey (2007). "Monteverdi, Claudio: Works from the Venetian years". In Macy, Laura (ed.). Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ^ a b Carter 2002, pp. 101–03.

- ^ a b c d Rosand & Vartolo, p. 1

- ^ Dunn 1972.

- ^ Rosand & Vartolo.

- ^ Carter 2002, p. 240.

- ^ a b c d Cascelli, Antonio (2007). Alan Curtis (ed.). "Claudio Monteverdi: Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria". Music & Letters. 88 (2). Oxford: 395–398. doi:10.1093/ml/gcl152.(subscription required)

- ^ Carter 2002, p. 238.

- ^ Rosand 2007b, pp. 55–58.

- ^ Ringer 2006, p. 217.

- ^ Carter 2002, p. 84.

- ^ Sadie 2004, pp. 46, 73.

- ^ Carter 2002, p. 237.

- ^ a b c d e f Kennedy 2006, p. 732

- ^ "Concert programmes: Cyril Eland collection". Arts and Humanities Research Council. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ^ Warrack & West 1992, p. 603.

- ^ Forbes, Elizabeth (5 January 2007). "Werner Hollweg (obituary)". The Independent. London. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- ^ Sadie, Stanley (4 September 1978). "Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria: Review". The Times. London. p. 9.

- ^ a b Harold C. Schonberg (January 20, 1974). "Opera: The Ulysses of Claudio Monteverdi Voyages to America in High Style". The New York Times.

- ^ "Central Opera Services Bulletin, Spring 1973" (PDF). Central Opera Services. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2007. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ^ "Classical Music and Dance Guide". The New York Times. 2 November 2001. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ^ The Independent on Sunday, ABC p. 13 A poignant homecoming, 24 September 2006

- ^ a b Cassaro, James P. (September 1987). "Claudio Monteverdi: Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria". Notes. 44. San Diego: Music Library Association: 166–67. doi:10.2307/941012. JSTOR 941012.(subscription required)

- ^ Gurewitsch, Matthew (29 February 2004). "Music: Into the Heart of Darkness, with Puppets". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ^ Ashby, Tim (24 August 2009). "Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria: Kings Theatre, Edinburgh". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ^ a b c Arnold, Denis. "Claudio Monteverdi: Three decades in Venice". Britannica Online. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ^ Johnson, David (May 1965). "For the Record". The North American Review. 250 (2). University of Northern Iowa: 63–64. JSTOR 25116167.(subscription required)

- ^ Noble, Jeremy (September 1971). "Monteverdi: Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria – complete". Gramophone. London: Haymarket. p. 100. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- ^ a b Arnold, Denis (December 1980). "The Return of Ulysses". Gramophone. London: Haymarket. p. 106. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ a b Ringer 2006, p. 143.

- ^ Carter 2002, p. 250.

- ^ a b Ringer 2006, p. 149.

- ^ a b Ringer 2006, pp. 200–01.

- ^ Ringer 2006, p. 211.

- ^ Rosand, Ellen (1995). "Monteverdi's Il ritorno d'Ulisse and the power of "music"". Cambridge Opera Journal. 7 (3). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 179–84. doi:10.1017/s0954586700004559. JSTOR 823638. S2CID 192021056.(subscription required)

- ^ a b Fenlon, Iain (March 1993). "Monteverdi Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria". Gramophone. London: Haymarket. p. 101. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ Beat 1968, p. 294.

- ^ Robinson 1972, p. 70.

- ^ Dunn 1972, p. 17.

- ^ "Monteverdi: Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria – complete". Gramophone. London: Haymarket. February 1972. p. 100. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ Arnold, Denis (December 1980). "The Return of Ulysses". Gramophone. London: Haymarket. p. 106. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ March 1993, p. 222.

- ^ Freeman-Attwood, Jonathan (April 2003). "Monteverdi: Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria". Gramophone. London: Haymarket. p. 95. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ Carter 2002, p. 5.

- ^ a b Carter 2002, p. 9.

Sources

[edit]- Badoaro, Giacomo (1972). Il ritorno d'Ulisse in Patria: Italian and English libretto. Translated by Geoffrey Dunn. London: Faber Music Ltd.

- Beat, Janet E. in (eds) Arnold, Denis and Fortune, Nigel (1968). The Monteverdi Companion. London: Faber and Faber.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Carter, Tim (2002). Monteverdi's Musical Theatre. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09676-3.

- Kennedy, Michael (2006). Oxford Dictionary of Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-861459-4.

- Neef, Sigrid, ed. (2000). Opera: Composers, Works, Performers (English ed.). Cologne: Könemann. ISBN 3-8290-3571-3.

- March, Ivan, ed. (1993). The Penguin Guide to Opera on Compact Disc. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-046957-5.

- Ringer, Mark (2006). Opera's First Master: The Musical Dramas of Claudio Monteverdi. Newark N.J.: Amadeus Press. ISBN 1-57467-110-3.

- Robinson, Michael F. (1972). Opera before Mozart. London: Hutchinson & Co. ISBN 0-09-080421-X.

- Rosand, Ellen (1991). Opera in Seventeenth-Century Venice: the Creation of a Genre. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-25426-0.

- Rosand, Ellen (2007). Monteverdi's Last Operas: a Venetian trilogy. Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24934-9.

- Rosand, Ellen and Vartolo, Sergio (2005). Preface to recording: Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria: Monteverdi's Five-Act Drama (CD). Leeuwarden (Netherlands): Brilliant Classics 93104.

- Sadie, Stanley, ed. (2004). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Opera. London: Flame Tree Publishing. ISBN 1-84451-026-3.

- Warrack, John; West, Ewan (1992). The Oxford Dictionary of Opera. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198691648.

External links

[edit]- Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Complete libretto (with Spanish translation)