Fulton J. Sheen

Fulton J. Sheen | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

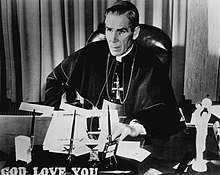

Sheen on the set of his show Life Is Worth Living | |||||||||||||||||

| Church | Catholic Church | ||||||||||||||||

| See | Rochester | ||||||||||||||||

| Appointed | October 21, 1966 | ||||||||||||||||

| Term ended | October 6, 1969 | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | James Edward Kearney | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Joseph Lloyd Hogan | ||||||||||||||||

| Other post(s) | Titular Archbishop of Neoportus (Latin: Newport, Wales; 1969–1979) | ||||||||||||||||

| Previous post(s) |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Orders | |||||||||||||||||

| Ordination | September 20, 1919 by Edmund M. Dunne | ||||||||||||||||

| Consecration | June 11, 1951 by Adeodato Giovanni Piazza | ||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||

| Born | Peter John Sheen May 8, 1895[1] El Paso, Illinois,[1] United States | ||||||||||||||||

| Died | December 9, 1979 (aged 84) New York City, United States | ||||||||||||||||

| Buried | St. Patrick's Cathedral, New York City (1979–2019) St. Mary's Cathedral, Peoria, Illinois (since 2019) | ||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | American | ||||||||||||||||

| Residence | Illinois; New York | ||||||||||||||||

| Occupation | Catholic bishop, evangelist, professor | ||||||||||||||||

| Education | |||||||||||||||||

| Motto | Da per matrem me venire (English: "Grant that I may come [to You] through the mother [Mary]") | ||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  | ||||||||||||||||

| Coat of arms |  | ||||||||||||||||

| Sainthood | |||||||||||||||||

| Shrines | Tomb (St. Mary's Cathedral, Peoria, Illinois) Birthplace museum in El Paso, Illinois Fulton Sheen Museum, Peoria | ||||||||||||||||

Ordination history | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Styles of Fulton J. Sheen | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | The Most Reverend |

| Spoken style | Your Excellency |

| Religious style | Your Excellency |

| Posthumous style | Venerable |

Fulton John Sheen (born Peter John Sheen, May 8, 1895 – December 9, 1979) was an American bishop of the Catholic Church known for his preaching and especially his work on television and radio. Ordained a priest of the Diocese of Peoria in Illinois, in 1919,[1] Sheen quickly became a renowned theologian, earning the Cardinal Mercier Prize for International Philosophy in 1923. He went on to teach theology and philosophy at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. and served as a parish priest before he was appointed auxiliary bishop of the Archdiocese of New York in 1951. He held this position until 1966 when he was made bishop of the Diocese of Rochester in New York. He resigned as bishop of Rochester in 1969[2] as his 75th birthday approached and was made archbishop of the titular see of Newport, Wales.

For 20 years as "Father Sheen", later monsignor, he hosted the night-time radio program The Catholic Hour on NBC (1930–1950) before he moved to television and presented Life Is Worth Living (1952–1957). Sheen's final presenting role was on the syndicated The Fulton Sheen Program (1961–1968) with a format that was very similar to that of the earlier Life Is Worth Living show. For that work, Sheen twice won an Emmy Award for Most Outstanding Television Personality, and was featured on the cover of Time magazine.[3] Starting in 2009, his shows were being re-broadcast on the EWTN and the Trinity Broadcasting Network's Church Channel cable networks.[4] His contribution to televised preaching resulted in Sheen often being called one of the first televangelists.[5]

The cause for his canonization was officially opened in 2002. In June 2012, Pope Benedict XVI officially recognized a decree from the Congregation for the Causes of Saints stating that he lived a life of "heroic virtues," a major step towards beatification, and he is now referred to as venerable.[6][7] On July 5, 2019, Pope Francis approved a reputed miracle that occurred through the intercession of Sheen, clearing the way for his beatification.[8] Sheen was scheduled to be beatified in Peoria on December 21, 2019, but his beatification was postponed after Bishop Salvatore Matano of Rochester expressed concern that Sheen's handling of a 1963 sexual misconduct case against a priest might be cited unfavorably in a forthcoming report from the New York Attorney General. The Diocese of Peoria countered that Sheen's handling of the case had already been "thoroughly examined" and "exonerated" and that Sheen had "never put children in harm's way".[9]

Early life

[edit]Fulton Sheen was born on May 8, 1895, in El Paso, Illinois, the oldest of four sons of Newton and Delia Sheen. His parents were of Irish descent, and their own parents were from Croghan, County Roscommon, Connacht. He was known as "Fulton", his mother's maiden name, but he was baptized as "Peter John Sheen".[1][10] As an infant, Sheen contracted tuberculosis.[11]

After the family had moved to nearby Peoria, Illinois, Sheen's first role in the Catholic Church was as an altar boy at Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Immaculate Conception in Peoria.[1][10]

Sheen graduated in 1913 from high school at Spalding Institute in Peoria with valedictorian honors. He then entered St. Viator College in Bourbonnais, Illinois. Deciding to become a priest, he started his studies at Saint Paul Seminary in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Ordination and further education

[edit]Sheen was ordained a priest for the Diocese of Peoria at the Cathedral of Saint Mary in Peoria on September 20, 1919 by Bishop Edmund Dunne.[1] After his 1919 ordination, Sheen continued his studies at the Catholic University of America.[10][12] He celebrated his first Christmas Mass at St. Mark Parish in Peoria [13] His youthful appearance was still evident on one occasion when a local priest asked Sheen to assist as altar boy during the celebration of the mass.[10]

After finishing his studies at Catholic University of America, he entered the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium, earning a Doctor of Philosophy degree in 1923.[12] [14] His thesis was titled "The Spirit of Contemporary Philosophy and the Finite God".[15] At Leuven, he became the first American to win the Cardinal Mercier Prize for the best philosophical treatise.[10] In 1924, Sheen went to Rome to attend the Pontificium Collegium Internationale Angelicum, where he was awarded a Doctor of Sacred Theology degree.[16][17]

Priestly life

[edit]After Sheen returned to Peoria in 1926, Bishop Dunn assigned him as curate at St. Patrick's, a poor parish in Peoria. At that time, both Columbia University in New York and Oxford University in England wanted him to teach philosophy. Sheen took the assignment at St. Patrick's without any complaints and later said that he enjoyed his time there. Nine months later, Dunne summoned Sheen to his office. Dunne told him:

I promised you to Catholic University over a year ago. They told me that with all your traipsing around Europe, you'd be so high hat you couldn't take orders. But Father Cullen says you've been a good boy at St. Patrick's. So run along to Washington.[18]

Instead of Catholic University of America, Sheen went to teach theology at St. Edmund's College, Ware, in England where he met Ronald Knox. He also assisted the pastor at St. Patrick's Church in the Soho section of London. In 1928, Sheen finally returned to the Catholic University of America, where he would teach philosophy until 1950.[19][10]

In 1929, Sheen gave a speech at a meeting of the National Catholic Educational Association in which he encouraged teachers to "educate for a Catholic Renaissance" in the United States. Sheen was hoping that Catholics would become more influential in their country through education, which would help attract others to the faith. He believed that Catholics should "integrate" their faith into the rest of their daily life.[20]

Bishop and archbishop

[edit]Sheen was consecrated a bishop on June 11, 1951[2] and served as an auxiliary bishop of the Archdiocese of New York from 1951 to 1966. The principal consecrator was the Discalced Carmelite Cardinal Adeodato Giovanni Piazza, the Cardinal-Bishop of Sabina e Poggio Mirteto and the Secretary of the Sacred Consistorial Congregation (now the Dicastery for Bishops). The co-consecrators were Archbishop Leone Giovanni Battista Nigris, Titular Archbishop of Philippi and the Secretary of the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (now the Dicastery for Evangelization); and Archbishop Martin John O'Connor, Titular Archbishop of Laodicea in Syria and President Emeritus of the Pontifical Council for Social Communications.

In 1966, Sheen was made the Bishop of Rochester. He served in this position from October 21, 1966, to October 6, 1969, when he resigned[2] and was made the archbishop of the titular see of Newport, Wales.

Ecumenical efforts

[edit]In the 1950s and 1960s, Sheen was notable for early efforts seeking common ground with Christians from non-Roman churches, both Eastern and Protestant. He occasionally celebrated Byzantine Divine Liturgy, with papal permission awarding him certain bi-ritual faculties.[21] He often commended Protestant devotion to Bible study: "The first subject of all to be studied is Scripture, and this demands not only the reading of it but the study of commentaries. ... Protestant commentaries, I discovered, were also particularly interesting because Protestants have spent more time on Scripture than most of us."[22]: 79 His autobiography summarized his ecumenical outlook: "The combination of travel, the study of world religions and personal encounter with different nationalities and peoples made me see that the fullness of truth is like a complete circle of 360 degrees. Every religion in the world has a segment of that truth."[22]: 148

Media career

[edit]Radio

[edit]A popular instructor, Sheen wrote the first of 73 books in 1925 and in 1930 began a weekly NBC Sunday-night radio broadcast, The Catholic Hour.[12] Sheen called World War II not only a political struggle but also a "theological one". He referred to Adolf Hitler as an example of the "Anti-Christ".[23] Two decades later, the broadcast had a weekly listening audience of four million people. Time referred to him in 1946 as "the golden-voiced Msgr. Fulton J. Sheen, U.S. Catholicism's famed proselytizer", and reported that his radio broadcast received 3,000–6,000 letters weekly from listeners.[24] During the middle of that era, he narrated the first religious service broadcast on the new medium of television and put into motion a new avenue for his religious pursuits.

Television

[edit]

At the Catholic University of America, Sheen provided voice-over commentary for an Easter Sunday Mass in 1940, one of the first televised religious services. During the sermon, which was telecast on experimental station W2XBS, Sheen remarked, "This is the first religious television in the history of the world. Let therefore its first message be a tribute of thanks to God for giving the minds of our day the inspiration to unravel the secrets of the universe."[25][26]

On February 12, 1952, he began a weekly television program on the DuMont Television Network, Life Is Worth Living.[27] Filmed at the Adelphi Theatre in New York City, the program consisted of the unpaid Sheen simply speaking in front of a live audience without a script or cue cards and occasionally using a chalkboard.

The show, scheduled in a prime time slot on Tuesday nights at 8:00 p.m., was not expected to challenge the ratings giants Milton Berle and Frank Sinatra but did surprisingly well. Berle, who was known to many early television viewers as "Uncle Miltie" and for using ancient vaudeville material, joked about Sheen, "He uses old material, too." He also observed, "If I'm going to be eased off the top by anyone, it's better that I lose to the One for whom Bishop Sheen is speaking."[10] Sheen responded in jest that maybe people should start calling him "Uncle Fultie".[28] Life and Time magazines ran feature stories on Sheen. The number of stations carrying Life Is Worth Living jumped from three to fifteen in less than two months. There was fan mail that flowed in at a rate of 8,500 letters per week. There were four times as many requests for tickets as could be fulfilled. Admiral, the sponsor, paid the production costs in return for a one-minute commercial at the show's opening and another minute at its close.[28] In 1952, Sheen won an Emmy Award for his efforts[29] and accepted the acknowledgment by saying, "I feel it is time I pay tribute to my four writers – Matthew, Mark, Luke and John." When Sheen won the Emmy, Berle quipped, "We both work for 'Sky Chief'", a reference to Berle's sponsor, Texaco. Time called him "the first 'televangelist'" and the Archdiocese of New York could not meet the demand for tickets.[10]

One of his best-remembered presentations came in February 1953, when he forcefully denounced the Soviet regime of Joseph Stalin. Sheen gave a dramatic reading of the burial scene from Shakespeare's Julius Caesar that substituted the names of prominent Soviet leaders Stalin, Lavrenty Beria, Georgy Malenkov, and Andrey Vyshinsky for the original Caesar, Cassius, Marc Antony, and Brutus. He concluded by saying, "Stalin must one day meet his judgment." Days later, the dictator suffered a stroke, and he died within the week.[30]

Indeed, Sheen was often quick to rebuke what he considered wrongful conduct. For example, in his televised sermon "False Compassion", he shouted: "There are sob sisters; there are the social slobberers who insist on compassion being shown to the muggers, to the dope fiends, to the throat slashers, to the beatniks, to the prostitutes, to the homosexuals, to the punks, so that today the decent man is practically off the reservation." He then clarified his criticism and charged his viewers with the responsibility to "hate the sin ... and love the sinner."[31]

The show ran until 1957 and drew as many as 30 million people weekly, mostly non-Catholics.[32] In 1958, Sheen became the national director of the Society for the Propagation of the Faith, serving for eight years before being appointed Bishop of the Diocese of Rochester, New York, on October 26, 1966. He also hosted a nationally-syndicated series, The Fulton Sheen Program, from 1961 to 1968, first in black-and-white and later in color. The format of the series was essentially the same as Life Is Worth Living.

International cassette tape ministry

[edit]In September 1974, the Archbishop of Washington, Thomas William Lyons, asked Sheen to be the speaker for a retreat for diocesan priests at the Loyola Retreat House in Faulkner, Maryland. It was recorded on reel-to-reel tape, which was then state-of-the-art.[33]

Sheen requested for the recorded talks to be produced for distribution. This was the first production of a worldwide cassette tape ministry called Ministr-O-Media, a nonprofit company that operated on the grounds of St. Joseph's Parish, Pomfret, Maryland. The retreat album was Renewal and Reconciliation and included nine 60-minute audiotapes.[33]

Evangelization

[edit]Sheen was credited with helping convert a number of notable figures to the Catholic faith, including the agnostic writer Heywood Broun, politician Clare Boothe Luce, automaker Henry Ford II, ex-communist writer Louis F. Budenz, ex-communist organizer Bella Dodd,[34] theatrical designer Jo Mielziner, violinist and composer Fritz Kreisler, and actress Virginia Mayo. Each conversion process took an average of 25 hours of lessons, and reportedly more than 95% of his students in private instruction were baptized.[10]

Falling-out with Cardinal Spellman

[edit]According to the foreword written for a 2008 edition of Sheen's autobiography, Treasure in Clay: The Autobiography of Fulton J. Sheen, the Catholic journalist Raymond Arroyo wrote why Sheen "retired" from hosting Life Is Worth Living "at the height of its popularity [...] [when] an estimated 30 million viewers and listeners tuned in each week."[35] Arroyo wrote that "It is widely believed that Cardinal Spellman drove Sheen off the air."[35]

Arroyo relates: "In the late 1950s, the government donated millions of dollars' worth of powdered milk to the New York Archdiocese. In turn, Cardinal Spellman handed that milk over to the Society for the Propagation of the Faith to distribute to the poor of the world. On at least one occasion, he demanded that the director of the Society, Bishop Sheen, pay the Archdiocese for the donated milk. He wanted millions of dollars. Despite Cardinal Spellman's considerable powers of persuasion and influence in Rome, Sheen refused. These were funds donated by the public to the missions, funds Sheen himself had personally contributed to and raised over the airwaves. He felt an obligation to protect them, even from the itchy fingers of his own Cardinal."[35]

Spellman later took the issue directly to Pope Pius XII by pleading his case with Sheen present. The Pope sided with Sheen. Spellman later confronted Sheen and stated, "I will get even with you. It may take six months or ten years, but everyone will know what you are like."[35] Besides being pressured to leave television, Sheen also "found himself unwelcome in the churches of New York City. Spellman canceled Sheen's annual Good Friday sermons at St. Patrick's Cathedral and discouraged clergy from befriending the Bishop."[35] In 1966, Spellman had Sheen reassigned to Rochester, New York, and caused his leadership at the Society for the Propagation of the Faith to be terminated although it was a position that he had held for 16 years, he had raised hundreds of millions of dollars for it, and he had personally donated $10 million of his earnings to it.[35] On December 2, 1967, Spellman died in New York City.

Sheen never talked about the situation and made only vague references to his "trials both inside and outside the Church".[35] In his autobiography, he even went so far as to praise Spellman.[35]

Later years

[edit]While serving in Rochester, he created the Sheen Ecumenical Housing Foundation. He also spent some of his energy on political activities such as his denunciation of the Vietnam War in late July 1967.[36] On Ash Wednesday in 1967, Sheen decided to give St. Bridget's Parish building to the federal Housing and Urban Development program. Sheen wanted to let the government use it for black Americans. There was a protest since Sheen acted on his own accord. The pastor disagreed by saying, "There is enough empty property around without taking down the church and the school." The deal fell through.[37]

On October 15, 1969, one month after celebrating his 50th anniversary as a priest, Sheen resigned from his Rochester position. He was then appointed archbishop of the titular see of Newport, Wales (Latin: Neoportus) by Pope Paul VI. The ceremonial position gave him a promotion to archbishop and helped him continue his extensive writing. Sheen wrote 73 books and numerous articles and columns.[29]

On October 2, 1979, two months before Sheen's death, Pope John Paul II visited St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York City, embraced Sheen, and said, "You have written and spoken well of the Lord Jesus Christ. You are a loyal son of the Church."[38]

Death and legacy

[edit]Beginning in 1977, Sheen "underwent a series of surgeries that sapped his strength and even made preaching difficult".[35] Throughout that time, he continued to work on his autobiography, parts of which "were recited from his sickbed as he clutched a crucifix."[35] Soon after an open-heart surgery at Lenox Hill Hospital,[29] Sheen died on December 9, 1979, in his private chapel while praying before the Blessed Sacrament.[3] He was interred in the crypt of St. Patrick's Cathedral near the deceased archbishops of New York, including Spellman. On June 27, 2019, Sheen's remains were transferred to The Cathedral of St. Mary in Peoria, IL, where his cause is being promoted for sainthood.[39]

The official repository of Sheen's papers, television programs, and other materials is at St. Bernard's School of Theology and Ministry in Rochester, New York.[40]

Joseph Campanella introduced the reruns of Sheen's various programs that are aired on EWTN. Reruns are also aired on the Trinity Broadcasting Network. In addition to his television appearances, Sheen can be heard on Relevant Radio.

The Fulton J. Sheen Museum, which is operated by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Peoria and located in Peoria, Illinois, houses the largest set of Sheen's personal items in five collections. The museum is located one block south of Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Immaculate Conception, where Sheen served as an altar boy, had his first communion and confirmation, was ordained and celebrated his first Mass.[41] Another museum is located in Sheen's hometown of El Paso, Illinois. The museum contains various Sheen artifacts but is not connected to the Diocese of Peoria.[42]

The Sheen Center for Thought & Culture, along Bleecker Street in Lower Manhattan, is named after him.[43]

The actor Ramón Gerard Antonio Estévez adopted the stage name of Martin Sheen partly in admiration of the bishop.[44]

Sheen did much of his preaching at Saint Agnes Church, in Midtown Manhattan, from 1927 to his death.[45][46] On October 7, 1980, New York Mayor Ed Koch renamed East 43rd Street in front of the church as "Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen Place".[47][48]

Cause for canonization

[edit]The Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen Foundation was formed in 1998 by Gregory J. Ladd and Lawrence F. Hickey to make known the archbishop's life. The foundation approached Cardinal John O'Connor of the Archdiocese of New York for permission to commence the process of his cause, which was under the authority of the Diocese of Peoria.[4] In 2002, Sheen's cause for canonization was officially opened by Bishop Daniel R. Jenky, CSC, of the Diocese of Peoria. From then on, Sheen was referred to as a "Servant of God". On February 2, 2008, the archives of Sheen were sealed at a ceremony during a special Mass at the Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Immaculate Conception in Peoria, Illinois, where the diocese was sponsoring his canonization.[29] In 2009, the diocesan phase of the investigation came to an end, and the records were sent to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints at the Holy See in Rome.

On June 28, 2012, the Holy See announced officially that it had recognized Sheen's life as one of "heroic virtue",[49] a major step towards eventual beatification. From then on, Sheen has been styled "Venerable Servant of God". According to the Catholic News Service and The Catholic Post (the official newspaper of the Peoria Diocese), the case of a newborn boy who had no discernible pulse for 61 minutes, who was about to be declared dead at OSF Saint Francis Medical Center in Peoria, Illinois, as a stillborn infant, and yet lived to be healthy without physical or mental impairment was in the preliminary stages of being investigated as the possible miracle needed for Sheen's potential beatification. If the miracle is approved at the diocesan level and then by the Congregation for the Causes of Saints at the Holy See, by being both medically unexplainable and directly attributable theologically to Sheen's intercession according to expert panels in both subject areas, beatification may proceed. Another such miracle would be required for him to be considered for canonization.

On September 7, 2011, a tribunal of inquiry was sworn in to investigate the alleged healing. During a special Mass at 10:30 am on Sunday, December 11, 2011, at St. Mary's Cathedral in Peoria, the documentation gathered by the tribunal over nearly three months was boxed and sealed. It was then shipped to the Holy See for consideration by the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, concluding the diocesan tribunal's work.[50]

On Sunday, September 9, 2012, a Mass of Thanksgiving and banquet was held at St. Mary's Cathedral and the Spalding Pastoral Center in celebration of the advancement of Archbishop Sheen's cause. Attendees included Bishop Jenky, and his predecessor as Bishop of Peoria, Archbishop John J. Myers of Newark, New Jersey, along with many clergy and religious from around the country. Copies of the positio, the book detailing the documentation behind his cause, were presented to Myers, representatives of the Church in other states, a delegate from the Archdiocese of Chicago, and other patrons and supporters of Sheen's cause. According to statements made during the service by clergy connected to the cause, the medical and theological study of the possible miracles needed for his beatification and canonization was well underway. At least one was being seriously considered. New procedures under Pope Benedict XVI stated that beatification should ideally occur in the candidate's home diocese. Therefore, Sheen's beatification would likely take place in Peoria, where it would be the first. If he is beatified and canonized, he would be among a select few natives of the US to hold that distinction.[51][52][53]

Transfer of remains

[edit]

In September 2014, it was announced that the canonization cause would be suspended because of a disagreement with the Archdiocese of New York concerning the return of Sheen's remains to the Diocese of Peoria.[54][55] In a press release on June 14, 2016, it was announced that Sheen's surviving family petitioned the New York Supreme Court to allow the transfer of Sheen's remains to Peoria. The press release stated that "on several occasions, the Archdiocese [of New York] has declared its desire to cooperate with the wishes of the family."[56]

In an action brought in New York Supreme Court, the trial-level court in New York, on November 16, 2016, Justice Arlene P. Bluth ordered the Archdiocese of New York to grant permission to disinter Sheen's body. The court ruled that the archdiocese's objection that Sheen would not want the disinterment was without factual basis. Given that his elevation to sainthood was being blocked, the court found the family had sufficient justification for moving his body.[57]

However, on February 6, 2018, the New York State Appellate Division overturned Bluth's decision and ordered an evidentiary hearing be held as to whether moving Sheen's body would be consistent with his wishes.[58] The court noted that "it is unclear if Archbishop Sheen's direction in his will to be buried in 'Calvary Cemetery, the official cemetery of the Archdiocese of New York' evinces an express intention to remain buried in the Archdiocese of New York, or was merely a descriptive term for Calvary Cemetery." However, after re-examining the case and holding the evidentiary hearing on June 9, 2018, Bluth affirmed her earlier ruling. The archdiocese had allowed Peoria to begin the work on his cause for canonization, which eventually would have required at the least a collection of his relics.[59]

The Archdiocese of New York announced on June 9, 2019 that it was officially giving up the fight to keep Sheen's remains under the altar at St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York.[60] On June 27, 2019, the remains were transferred to St. Mary's Cathedral in Peoria.[39]

Miracle recognized for beatification

[edit]On July 6, 2019, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints promulgated the decree approving Sheen's miracle needed for beatification. The miracle involved the unexplained recovery of James Fulton Engstrom, a boy stillborn in September 2010 to Bonnie and Travis Engstrom of the town of Goodfield, near Peoria. Engstrom's parents prayed for the intercession of Sheen for their son's recovery. Pope Francis approved the miracle, and Sheen was scheduled for beatification on December 21, 2019, at the Cathedral of St. Mary in Peoria.[61][62]

Postponement of beatification

[edit]On December 3, 2019, the Diocese of Peoria announced that the Holy See had decided on December 2 that Sheen's beatification would be "postponed".[63] The postponement was prompted by Salvatore Matano, Bishop of Rochester, who expressed concern that his predecessor's handling of a 1963 sexual misconduct case against a priest might be cited unfavorably in a report from New York State Attorney General Letitia James. The Diocese of Peoria countered that Sheen's handling of the case had already been "thoroughly examined" and "exonerated" and that Sheen had "never put children in harm's way."[9] The Diocese of Peoria continues to promote the beatification of Sheen.[64]

As of August 2023, the Holy See had not announced whether or when the beatification would move ahead.[65] As of April 2024, New York State's Rochester investigation was still ongoing.[66]

Selected bibliography

[edit]- God and Intelligence in Modern Philosophy (1925, Longmans, Green, and Co.)

- The Seven Last Words (1933, The Century Co.)

- Philosophy of Science (1934, Bruce Publishing Co.)

- The Eternal Galilean (1934, Appleton-Century-Crofts)

- The Mystical Body of Christ (1935, Sheed and Ward)

- Calvary and the Mass (1936, P. J. Kenedy & Sons)

- The Cross and the Beatitudes (1937, P. J. Kenedy & Sons)

- Seven Words of Jesus and Mary (1945, P. J. Kenedy & Sons)

- Communism and the Conscience of the West (1948, Bobbs-Merrill)

- Peace of Soul (1949, McGraw–Hill)[67]

- Three to Get Married (1951, Appleton-Century-Crofts)

- The World's First Love (1952, McGraw-Hill)

- Life Is Worth Living Series 1–5 (1953–1957, McGraw–Hill)

- Way to Happiness (1953, Maco Magazine)

- Way to Inner Peace (1955, Garden City Books)

- Life of Christ (1958, McGraw–Hill)

- Missions and the World Crisis (1963, Bruce Publishing Co.)

- The Power of Love (1965, Simon & Schuster)

- Footprints in a Darkened Forest (1967, Meredith Press)

- Lenten and Easter Inspirations (1967, Maco Ecumenical Books)

- Treasure in Clay: The Autobiography of Fulton J. Sheen (1980, Doubleday & Co.)

- Finding True Happiness (2014, Dynamic Catholic)

- Your Life Is Worth Living: 50 Lessons to Deepen Your Faith, Foreword by Bishop Robert Barron (2019, Image Catholic Books)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Biography – Archbishop Fulton Sheen". Archbishop Fulton John Sheen Foundation. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Archbishop Fulton John Sheen". Catholic-Hierarchy.org. David M. Cheney. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ^ a b "Biography of Fulton J. Sheen". Catholic University of America. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ a b "Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen". Archived from the original on May 13, 2008. Retrieved September 14, 2009.

- ^ Rodgers, Ann (August 29, 2006). "Emmy-winning televangelist on path toward sainthood: Sheen would be 1st American-born man canonized". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved July 16, 2012 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ Otterman, Sharon (June 29, 2012). "For a 1950s TV Evangelist, a Step Toward Sainthood". The New York Times. Retrieved July 5, 2012.

- ^ "The Venerable Fulton J. Sheen: a model of virtue for our time". News.va. Pontifical Council for Social Communications. June 30, 2012. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved July 5, 2012.

- ^ "Archbishop Fulton Sheen to be beatified", America. Associated Press, July 6, 2019.

- ^ a b Flynn, J.D.; Condon, Ed (December 4, 2019). "Rochester bishop requested Fulton Sheen beatification delay". Catholic News Agency. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Bishop Fulton Sheen: The First 'Televangelist'". Time. April 14, 1952. Archived from the original on January 22, 2008. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ Fulton J. Sheen. Treasure in Clay, Ch. 2 "The Molding of the Clay", p. 9, 1980.

- ^ a b c "About Fulton J. Sheen". Fulton J. Sheen website. Archived from the original on October 20, 2007.

- ^ Reeves, Thomas C. (2001). America's Bishop: The Life and Times of Fulton J. Sheen. San Francisco: Encounter Books. p. 56. ISBN 1-893554-25-2.

- ^ Sheen Cunningham, Joan; Rodriguez, Janel (2019). My Uncle Fulton Sheen. Ignatius Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-1-64229-110-0.

- ^ Sheen, Fulton John. "The Spirit of Contemporary Philosophy and the Finite God", Thèse de doctorat – Université catholique de Louvain, 1923.

- ^ Queen, Edward L.; Prothero, Stephen R.; Shattuck, Gardiner H. (2009). Encyclopedia of American Religious History. Facts On File, Incorporated. p. 921. ISBN 978-0816066605. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ^ "Archbishop Fulton Sheen dies". Catholic Post. Peoria. December 16, 1979. Retrieved December 30, 2013 – via El Paso, Illinois, Community History Webpage.

- ^ Farney, Kirk D. (June 21, 2022). Ministers of a New Medium: Broadcasting Theology in the Radio Ministries of Fulton J. Sheen and Walter A. Maier. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-1-5140-0323-7.

- ^ "Fulton J. Sheen, Catholic Champion". Catholiceducation.org. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ Hennesey, James (1981). American Catholics, Oxford University Press, p. 255.

- ^ "Byzantine Mass [sic] Offered by Sheen; Bishop, With Papal Sanction, Celebrates in Ancient Rite in Slavonic and English". The New York Times. June 18, 1956.

- ^ a b Sheen, Fulton J. (1993). Treasure in Clay: The Autobiography of Fulton J. Sheen. Ignatius Press.

- ^ Hennesey, James (1981). American Catholics, Oxford University Press, p. 280.

- ^ "Radio Religion". Time. January 21, 1946. Archived from the original on January 25, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2009.

- ^ "First Television Broadcast Of Easter Services". The Gazette and Daily. Associated Press. March 24, 1940. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Sheen, Fulton J., narrator (1941). The Eternal Gift (Videotape). The Perpetual Novena.

- ^ Weiner, Ed (1992). The 'TV Guide' TV Book. New York: Harper Collins. p. 216. ISBN 0-06-096914-8.

- ^ a b Watson, Mary Ann (1999). "And they said Uncle Fultie didn't have a prayer." Television Quarterly, 30 (2), 80–85.

- ^ a b c d Bearden, Michelle (January 24, 2009). "Mass Today Promotes Sheen For Sainthood". The Tampa Tribune. p. 10.

- ^ Mikkelson, Barbara and David P. "Stalin for Time: Did Bishop Fulton Sheen foretell the death of Stalin?" Snopes, August 8, 2007.

- ^ Sheen, Fulton J. (1965). "False Compassion". The Fulton Sheen Program. The Catholic World. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ Keane, James T. (January 10, 2023). "The secret to Archbishop Fulton Sheen's power: 'A thinking head and a feeling heart'". America. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ a b "An Enduring Journey of Faith: St. Joseph's Parish, Pomfret, Maryland, 2012" by St. Joseph's Church, Pomfret, Maryland, Harambee Productions, White Plains, Maryland.

- ^ Briton Hadden; Henry Robinson Luce (1952). Time. Time Incorporated. p. 52.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sheen, Fulton J. (2008). Treasure in Clay: The Autobiography of Fulton J. Sheen. Doubleday.

- ^ Willbanks, James H., Vietnam War Almanac, Facts on File, Inc. (2009), p. 215.

- ^ John T. McGreevy, Parish Boundaries: The Catholic Encounter with Race in the Twentieth-Century Urban North, University of Chicago Press, 1996, 242

- ^ "The Cause for Canonization". Catholic University of America. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ a b "Venerable Archbishop Fulton Sheen remains transferred to Peoria". Heart of Illinois ABC. June 27, 2019. Archived from the original on June 27, 2019. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ^ The Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen Archives accessed August 15, 2007 Archived February 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen Museum". Catholic Diocese of Peoria.

- ^ "Archbishop Sheen Museum". Archbishop Fulton John Sheen Spiritual Centre. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ "About the Sheen Center", Sheen Center for Thought & Culture.

- ^ "Martin Sheen on Why He Changed His Name & Emilio Estevez on Why He Didn't Change His Name". Hudson Union Society, 2012.

- ^ Haberman, Clyde; Krebs, Albin (April 12, 1979). "Notes on People: Archbishop Sheen to Preach at St. Agnes's Tomorrow". The New York Times. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

Sheen intends to continue tomorrow a tradition begun in 1927.

- ^ Lajoie, Ron (May 18, 2011). "St. Agnes Exhibit Looks at Archbishop Sheen's On-air Ministry". Catholic New York. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

For many years the church hosted his famous broadcasts. His last Good Friday homily was preached at the church in 1979.

- ^ "About Us". Church of Saint Agnes. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

It was at Saint Agnes Church that his sermons were carried throughout the world.

- ^ Gertner, Larry; Herrick, Michael. "Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen Place Historical Marker". The Historical Marker DataBase. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

October 7, 1980: Mayor Edward Koch proclaimed East 43rd Street between Lexington & Third Aves. Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen Place

- ^ Decrees of the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints, June 28, 2012. Vatican Information Service, June 28, 2012.

- ^ Dermody, Tom (December 13, 2011). "Evidence of alleged miracle with Sheen link heads to Rome". The Catholic Post. Catholic Diocese of Peoria. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ^ "Archbishop Fulton Sheen Foundation". Fultonsheen.blogspot.com. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- ^ "Celebrate Sheen!". Celebrate Sheen!. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- ^ "World needs Archbishop Sheen's example of faith, virtue, says homilist". Catholic News Service. September 11, 2012. Archived from the original on January 18, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- ^ "Sheen cause suspended, call for prayer". The Catholic Post. September 3–5, 2014. Archived from the original on September 9, 2014.

- ^ "Statement concerning the cause of Venerable Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen" (Press release). Archdiocese of New York. September 4, 2014.

- ^ "Family petitions court to move the body of Archbishop Fulton Sheen to Peoria" (Press release). Archbishop Fulton Sheen Foundation. June 14, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ^ "Cunningham v. Trustees of St. Patrick's Cathedral". November 16, 2016.

- ^ "Matter of Cunningham v Trustees of St. Patrick's Cathedral". New York State Law Reporting Bureau. February 6, 2018.

- ^ "Civil court rules Fulton Sheen's remains can go to Peoria". Catholic News Agency. June 9, 2018.

- ^ Lapin, Tamar (June 9, 2019). "Archdiocese of New York gives up fight over Bishop Sheen's remains". New York Post. Retrieved June 10, 2019.

- ^ Mares, Courtney (July 6, 2019). "Archbishop Fulton Sheen to be beatified". Catholic News Agency.

- ^ "Venerable Fulton Sheen to be beatified in December". Catholic News Agency. November 18, 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ "Postponement of Beatification" (Press release). Catholic Diocese of Peoria. December 3, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ "Peoria diocese continues promoting Sheen's beatification cause". Catholic News Agency. May 10, 2021. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Flynn, J.D. (August 16, 2023). "Will Fulton Sheen finally be beatified?". The Pillar. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ Payne, Daniel (April 17, 2024). "New York prosecutor, Brooklyn Diocese reach agreement over sex abuse mishandling". Catholic News Agency. Retrieved April 17, 2024.

(New York State Attorney General) Letitia James on Tuesday noted that investigations into the Archdiocese of New York, as well as into the Dioceses of Albany, Ogdensburg, Rochester, Rockville Centre, and Syracuse, remain ongoing.

- ^ This book was Sheen's response to Rabbi Joshua L. Liebman's 1946 best-seller Peace of Mind.

Further reading

[edit]- Farney, Kirk D. (2022). Ministers of a New Medium: Broadcasting Theology in the Radio Ministries of Fulton J. Sheen and Walter A. Maier. IVP Academic

- Reeves, Thomas C. (2001). America's Bishop: The Life and Times of Fulton J. Sheen. Encounter Books, San Francisco.

- Riley, Kathleen L. (2004). Fulton J. Sheen: An American Catholic Response to the Twentieth Century. St. Paul's/Alba House, Staten Island.

- Sherwood, Timothy H. (2010). The Preaching of Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen: The Gospel Meets the Cold War. Lexington Books.

- Sherwood, Timothy H. (2013). The Rhetorical Leadership of Fulton J. Sheen, Norman Vincent Peale, and Billy Graham in the Age of Extremes. Lexington Books.

- Winsboro, Irvin D. S. & Epple, Michael (Summer 2009). "Religion, Culture, and the Cold War: Bishop Fulton J. Sheen and America's Anti-Communist Crusade of the 1950s", Historian, 71 (2): 209–233.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Fulton J. Sheen at IMDb

- The Archbishop Fulton John Sheen Foundation

- Library Catalog Record for Sheen's Ph.D. thesis

- FBI file on Bishop Sheen

- Venerable Fulton J. Sheen: 200 talks by Sheen available in MP3 format, along with streaming video of his Family Retreat

- Time cover, Fulton J. Sheen, April 14, 1952

- Fulton J. Sheen Spiritual Centre – El Paso, IL Archived April 1, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- Sheen Mass – Cause for Canonization on YouTube

- 1895 births

- 1979 deaths

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American non-fiction writers

- 20th-century American Roman Catholic titular archbishops

- 20th-century Roman Catholic bishops in the United States

- 20th-century venerated Christians

- American anti-communists

- American male non-fiction writers

- American people of Irish descent

- American religious writers

- American Roman Catholic writers

- American television evangelists

- American venerated Catholics

- Burials at St. Patrick's Cathedral (Manhattan)

- Catholic television

- Catholic University of America alumni

- Catholic University of America faculty

- Catholic University of Leuven (1834–1968) alumni

- Catholics from Illinois

- Members of the Order of the Holy Sepulchre

- Participants in the Second Vatican Council

- People from El Paso, Illinois

- People from Peoria, Illinois

- Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas alumni

- Primetime Emmy Award winners

- Religious mass media in the United States

- Roman Catholic bishops in New York (state)

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Rochester

- Saint Paul Seminary alumni

- St. Viator College alumni

- Venerated Catholics by Pope Benedict XVI

- Writers from Illinois

- Writers from New York City