Jack Daniel's

| |

| Company type | Subsidiary of Brown–Forman |

|---|---|

| Industry | Manufacturing and distillation of liquors |

| Founded | Lynchburg, Tennessee (1875) |

| Founder | Jack Daniel |

| Headquarters | Lynchburg, Tennessee , U.S. |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people |

|

| Products | Distilled and blended liquors |

Production output | 16.1 million cases (38,300,000 US gal or 144,900,000 L) (2017)[1] |

| $121,700,000 | |

Number of employees | Over 500[2] |

| Parent | Brown–Forman Corporation |

| Website | jackdaniels |

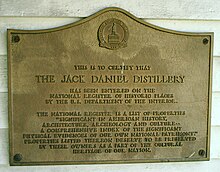

Jack Daniel Distillery | |

| |

| Location | TN 55 Lynchburg, Tennessee |

|---|---|

| NRHP reference No. | 72001248 |

| Added to NRHP | September 14, 1972 |

Jack Daniel's is a brand of Tennessee whiskey. It is produced in Lynchburg, Tennessee, by the Jack Daniel Distillery, which has been owned by the Brown–Forman Corporation since 1956.

Packaged in square bottles, Jack Daniel's "Black Label" Tennessee whiskey sold 12.9 million nine-liter cases in 2017. Other brand variations, such as Tennessee Honey, Tennessee Apple, Gentleman Jack, Tennessee Fire, and ready to drink (RTD) products brought the total to more than 16.1 million equivalent adjusted cases for the entire Jack Daniel's family of brands.

Early life of Jasper Daniel

[edit]The Jack Daniel's brand's official website suggests that its founder, Jasper Newton "Jack" Daniel, was born in 1850 (his tombstone bears that date[3]), but says his exact birth date is unknown.[4] The company website says it is customary to celebrate his birthday in September.[4] According to the Tennessee state library website in 2013, records list his birth date as September 5, 1846. It maintains that the 1850 birth date seems impossible since his mother died in 1847.[3] In the 2004 biography Blood & Whiskey: The Life and Times of Jack Daniel, author Peter Krass said his investigation showed that Daniel was born in January 1849 (based on Jack's sister's diary, census records, and the date of death of Jack's mother).[5]

Jack was the youngest of 10 children born to his mother, Lucinda (Cook) Daniel, and father Calaway Daniel. After Lucinda's death, his father remarried and had three more children.[5] Calaway Daniel's father, Joseph "Job" Daniel, had emigrated from Wales to the United States with his Scottish wife, the former Elizabeth Calaway.[6] Jack Daniel's ancestry included English, and Scots-Irish as well.[7][better source needed]

Jack did not get along with his stepmother. After Daniel's father died in the Civil War, the boy was legally adopted by a family friend named Felix Waggoner, but was soon taken in by another local farmer named Dan Call.[8][5]

Career of Jasper Daniel

[edit]

As a teenager, Daniel was taken in by Dan Call, a local lay preacher and moonshine distiller. He began learning the distilling trade from Call and his Master Distiller, Nathan "Nearest" Green, an enslaved African-American man. Green was known to specialize in the Lincoln County Process, a distilling process that filters the whiskey through sugar maple charcoal.[9] This process created the distinction between bourbon and the Tennessee Whiskey known today. While under Green as an apprentice, Daniel was taught the Lincoln Country Process.[9][10] Green continued to work with Call after emancipation.[8]

In 1875, on receiving an inheritance from his father's estate (following a long dispute with his siblings), Daniel founded a legally registered distilling business with Call. He took over the distillery shortly afterward when Call quit for religious reasons.[8][5] The brand label on the product says "Est. & Reg. in 1866", but his biographer has cited official registration documents, asserting that the business was not established until 1875.[3][8]

After taking over the distillery in 1884, Daniel purchased the hollow and land where the distillery is now located.[8][6] By the 1880s, Jack Daniel's was one of 15 distilleries operating in Moore County, and the second-most productive behind Tom Eaton's Distillery.[11] He began using square-shaped bottles, intended to convey a sense of fairness and integrity, in 1897.[8][5]

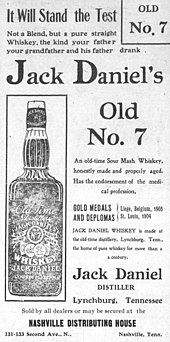

According to Daniel's biographer, the origin of the "Old No. 7" brand name was the number assigned to Daniel's distillery for government registration.[8][5] He was forced to change the registration number when the federal government redrew the district, and he became Number 16 in district 5 instead of No. 7 in district 4. However, he continued to use his original number as a brand name, since the brand reputation had already been established.[8][5] An entirely different explanation is given in the 1967 book Jack Daniel's Legacy which states that the name was chosen in 1887 after a visit to a merchant friend in Tullahoma, who had built a chain of seven stores.[12]

Jack Daniel's had a surge in popularity after the whiskey received the gold medal for the finest whiskey at the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair. However, its local reputation began to suffer as the temperance movement began gaining strength in Tennessee.[8][5][6]

Jack Daniel never married and did not have any known children. He took his nephews under his wing – one of whom was Lemuel "Lem" Motlow (1869–1947).[8][5] Lem, a son of Daniel's sister, Finetta,[6] was skilled with numbers. He soon took responsibility for the distillery's bookkeeping.[citation needed]

In failing health, Jack Daniel gave the distillery to Lem Motlow and another nephew in 1907.[8][5] Motlow soon bought out his partner, and went on to operate the distillery for about 40 years.[citation needed]

Tennessee passed a statewide prohibition law in 1910, effectively barring the legal distillation of Jack Daniel's within the state. Motlow challenged the law in a test case that eventually worked its way to the Tennessee Supreme Court. The court upheld the law as constitutional.[14][15]

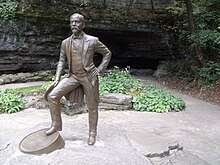

Daniel died in 1911 from blood poisoning. An oft-told tale is that the infection began in one of his toes, which Daniel injured one early morning at work by kicking his safe in anger when he could not get it open (he was said to always have had trouble remembering the combination).[16] But Daniel's modern biographer has asserted that this account is not true.[8][5]

Because of prohibition in Tennessee, the company shifted its distilling operations to St Louis, Missouri, and Birmingham, Alabama. None of the production from these locations was ever sold due to quality problems.[17] The Alabama operation was halted following a similar statewide prohibition law in that state, and the St. Louis operation fell to the onset of nationwide prohibition following passage of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1920.[citation needed]

While the passage of the Twenty-first Amendment in 1933 repealed prohibition at the federal level, state prohibition laws (including Tennessee's) remained in effect, thus preventing the Lynchburg distillery from reopening. Motlow, who had become a Tennessee state senator, led efforts to repeal these laws, which allowed production to restart in 1938. The five-year gap between national repeal and Tennessee repeal was commemorated in 2008 with a gift pack of two bottles, one for the 75th anniversary of the end of prohibition and a second commemorating the 70th anniversary of the reopening of the distillery.[18]

The Jack Daniel's distillery ceased operations from 1942 to 1946 when the U.S. government banned the manufacture of whiskey due to World War II. Motlow resumed production of Jack Daniel's in 1947 after good-quality corn was again available.[17] Motlow died the same year, bequeathing the distillery to his children, Robert, Reagor, Dan, Conner, and Mary, upon his death.[19]

The company was later incorporated as "Jack Daniel Distillery, Lem Motlow, Prop., Inc.", allowing the company to continue to include Motlow in its tradition-oriented marketing. Likewise, company advertisements continue to use Lynchburg's 1960s-era population figure of 361, though the city has since formed a consolidated city-county government with Moore County. Its official population is more than 6,000, according to the 2010 census.

The company was sold to the Brown–Forman Corporation in 1956.[20]

The Jack Daniel's Distillery was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972.[citation needed]

In 2012 a Welshman, Mark Evans, claimed to have discovered the original recipe for Daniel's whiskey in a book written in 1853 by his great-great-grandmother. Evans said that his great-great-grandmother's brother-in-law, John "Jack the lad" Daniels, had taken the recipe to Tennessee.[21]

Recent history

[edit]Lowering to 80 proof

[edit]

Until 1987, Jack Daniel's black label was historically produced at 90 U.S. proof (45% alcohol by volume).[22] The lower-end green label product was 80 proof. However, starting in 1987, the other label variations also were reduced in proof. This began with black label being initially reduced to 86 proof. Both the black and green label expressions are made from the same ingredients; the difference is determined by professional tasters, who decide which of the batches would be sold under the "premium" black label, with the rest being sold as "standard" green label.

A further dilution began in 2002 when all generally available Jack Daniel's products were reduced to 80 proof, thus further lowering production costs and excise taxes.[23][24] This reduction in alcohol content, which was done without any announcement, publicity or change of logo or packaging,[24] was noticed and condemned by Modern Drunkard Magazine, and the magazine formed a petition drive for drinkers who disagreed with the change.[23] The company countered that it believed consumers preferred lower-proof products, and said that the change had not hurt the sales of the brand.[23][24] The petition effort garnered some publicity and collected more than 13,000 signatures, but the company held firm with its decision.[23] A few years later, Advertising Age said in 2005 that "virtually no one noticed" the change, and confirmed that sales of the brand had actually increased since the dilution began.[24]

Jack Daniel's has also produced higher-proof special releases and premium-brand expressions at times. A one-time limited run of 96 proof, the highest proof Jack Daniel's had ever bottled at that time, was bottled for the 1996 Tennessee Bicentennial in a decorative bicentennial bottle. The distillery debuted its 94 proof "Jack Daniel's Single Barrel" in February 1997. The Silver Select Single Barrel was formerly the company's highest proof at 100, but is available only in duty-free shops. Now, there are 'single barrel barrel proof' editions, ranging from 125 to 140 proof.

Sales and brand value status

[edit]Jack Daniel's Black Label Tennessee Whiskey is the best-selling whiskey in the world[25] and remains the flagship product of Brown–Forman Corporation. In 2017 the product had sales of 12.9 million cases.[26] Underlying net sales for the Jack Daniel's brand grew by 3% (−1% on a reported basis).[clarification needed] Other brand variations, such as Tennessee Honey, Gentleman Jack, and Tennessee Fire, added another 2.9 million cases to sales. Sales of an additional 800,000 equivalent cases in ready to drink (RTD) products brought the fiscal year total to more than 16.1 million equivalent adjusted cases for the entire Jack Daniel's family of brands.[1]

Tennessee Honey and Tennessee Fire were also solid contributors to the total underlying net sales growth of 3% (flat on a reported basis) for the Jack Daniel's family of brands. They grew underlying net sales by 4% and 14% (3% and 18% on a reported basis), respectively. Premium brand Gentleman Jack grew underlying net sales mid-single digits, while the RTD/RTP segment increased underlying net sales by 6% (3% on a reported basis).[1]

In the IWSR 2013 World Class Brands rankings of wine and spirits brands, Jack Daniel's was ranked third on the global level.[27] More recently, in 2017, it ranked at number 16 on the IWSR's Real 100 Spirits Brands Worldwide list.[28] Additionally, the brand evaluation consultancy Intangible Business ranked Jack Daniel's fourth on its Power 100 Spirits and Wine list in both 2014 and 2015.[29][30]

Sponsorships

[edit]

From 2006 until 2015, Jack Daniel's sponsored V8 Supercar teams Perkins Engineering and Kelly Racing.[31] Jack Daniel's also sponsored the Richard Childress Racing 07 car (numbered after the "Old No. 7") in the NASCAR Sprint Cup Series from 2005 to 2009, beginning with driver Dave Blaney and soon moving to Clint Bowyer.[32] Jack Daniel's also sponsors Zac Brown Band's tours.

In September 2022, Jack Daniel's signed a multi-year partnership deal with McLaren starting from the 2023 season onwards.[33] As part of the partnership, Jack Daniel's released a McLaren Racing limited edition of the Old No. 7 which paid tribute to the founders of both companies – Jack Daniel and Bruce McLaren.[34] For the 2023 Las Vegas Grand Prix, McLaren raced a special Jack Daniel's branded livery with a Jack Daniel's collage highlighted across both cars' rear sidepod and engine cover.[35]

Master distillers

[edit]Former Master Distillers include Nathan "Nearest" Green (1875–81),[36] Jess Motlow (1911–41), Lem Tolley (1941–64), Jess Gamble (1964–66), and Frank Bobo (1966–92).[37]

Jimmy Bedford held the position for 20 years.[38] Bedford retired in mid-2008 after being the subject of a $3.5 million sexual harassment lawsuit against the company that ended in an out-of-court settlement, and he died on August 7, 2009, after suffering a heart attack at his home in Lynchburg.[38][39]

Jeff Arnett, a company employee since 2001, became Master Distiller in 2008. On September 3, 2020, Arnett announced that he was stepping down from the company.[40] On April 20, 2021, he announced that he and partners were opening Company Distilling, a new whiskey distillery, near the Great Smokey Mountains.[41]

Chris Fletcher became the 8th Master Distiller in 2020 after serving as Assistant Master Distiller for six years prior. Fletcher is the grandson of former Master Distiller, Frank Bobo.[42]

Tennessee Squires

[edit]A Tennessee Squire is a member of the Tennessee Squire Association, which was formed in 1956 to honor special friends of the Jack Daniel's distillery.[43] Many prominent business and entertainment professionals are included among the membership, which is obtained only through recommendation of a current member. Squires receive a wallet card and deed certificate proclaiming them as "owner" of an unrecorded plot of land at the distillery and an honorary citizen of Moore County, Tennessee.[44][non-primary source needed]

Production process

[edit]

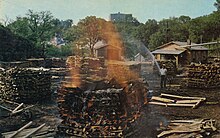

The mash for Jack Daniel's is composed of 80% corn, 12% rye, and 8% malted barley, and is distilled in copper stills.[45] It is then filtered through 10-foot (3.0 m) stacks of sugar maple charcoal.[46] The company refers to this filtering step as "mellowing". This extra step, known as the Lincoln County Process, removes impurities and the taste of corn.[6][47] The company argues this extra step makes the product different from bourbon. However, Tennessee whiskey is required to be "a straight Bourbon Whiskey" under terms of the North American Free Trade Agreement[48] and Canadian law.[49] A distinctive aspect of the filtering process is that the Jack Daniel's brand grinds its charcoal before using it for filtering.[50] After the filtering, the whiskey is stored in newly handcrafted oak barrels, which give the whiskey its color and most of its flavor.[46]

The product label mentions that it is a "sour mash" whiskey, which means that when the mash is prepared, some of the wet solids from a previously used batch are mixed in to help make the fermentation process operate more consistently. This is common practice in American whiskey production. (As of 2005[update], all straight bourbon is produced using the sour mash process.[51])

Prior to 2014, the company's barrels were produced by Brown-Forman in Louisville, Kentucky. That year, the company opened a new cooperage in Trinity, Alabama.[52][53]

Legal status

[edit]On a state level, Tennessee has imposed stringent requirements. To be labeled as Tennessee whiskey, it is not enough under state law that the whiskey be produced in Tennessee; it must meet quality and production standards. These are the same standards used by Jack Daniel's Distillery, and some other distillers are displeased with the requirements being enshrined into law.[54][55]

On May 13, 2013, Tennessee Governor Bill Haslam signed House Bill 1084, requiring the Lincoln County process to be used for products produced in the state labeling themselves as "Tennessee Whiskey", with a particular exception tailored to exempt Benjamin Prichard's, and including the existing requirements for bourbon.[55][56] As federal law requires statements of origin on labels to be accurate, the Tennessee law effectively gives a firm definition to Tennessee whiskey, requiring Tennessee origin, maple charcoal filtering by the Lincoln County process prior to aging, and the basic requirements of bourbon (at least 51% corn, new oak barrels, charring of the barrels, and limits on alcohol by volume concentration for distillation, aging, and bottling).[55]

In 2014 legislation was introduced in the Tennessee legislature that would modify the 2013 law to allow the reuse of oak barrels in the Tennessee whiskey aging process. Jack Daniel's Master Distiller Jeff Arnett vehemently opposed the legislation, arguing the reuse of barrels would require the use of artificial colorings and flavorings, and would render Tennessee whiskey an inferior product to Scotch and bourbon.[57]

The company was the subject of a proposal to locally surtax its product in 2011. It was claimed that the distillery, the main employer in a company town, had capitalized on the bucolic image of Lynchburg, Tennessee, and it ought to pay a tax of $10 per barrel. The company responded that such a tax is a confiscatory imposition penalizing it for the success of the enterprise.[58] The proposed tax faced a vote by the Metro Lynchburg-Moore County Council and was defeated 10–5.[59]

Moore County, where the Jack Daniel's distillery is located, is one of the state's many dry counties. While it is legal to distill the product within the county, it is illegal to purchase it there.[60][failed verification] However, a state law has provided one exception: a distillery may sell one commemorative product at a time, regardless of county statutes.[61][full citation needed]

Labels

[edit]- Old No. 7, also known as "Black Label": this is the original Jack Daniel's label (80 proof/40% ABV; previously 90 proof/45% ABV until 1987).

- Gentleman Jack: Charcoal filtered twice, compared to once with Old No. 7 (80 proof/40% ABV)

- Single Barrel: (94 proof/47% ABV)

- 1907: sold in the Australian market (74 proof/37% ABV)

- Añejo Tequila Barrel-Finished Tennessee Whiskey: limited edition

- Bottled-In-Bond only on military bases (100 proof/50% ABV)

- Green Label: A lighter-bodied bottling of Old No. 7 (80 proof/40% ABV)

- No. 27 Gold: Limited release (80 proof/40% ABV)

- Silver Select: (100 proof/50% ABV).

- Sinatra Select: named for Frank Sinatra (90 proof / 45% ABV)

- Sinatra Century: limited edition released for Sinatra's 100th birthday (100 proof / 50% ABV)

- Single Barrel Barrel Proof (125–140 proof / 62.5–70% ABV)

- Single Barrel Rye: launched 2016 (94 proof/47% ABV)[62]

- Single Barrel Select Eric Church Edition (94 proof/47% ABV)

- Tennessee Rye: (90 proof/45% ABV)

Liqueur

[edit]- Tennessee Honey: Honey liqueur blended with less than 20% whiskey (70 proof/35% ABV)

- Tennessee Fire: Cinnamon liqueur blended with less than 20% whiskey (70 proof/35% ABV)

- Tennessee Apple: Apple liqueur blended with less than 20% whiskey (70 proof/35% ABV)

- Winter Jack: Seasonal blend of apple cider liqueur and spices (30 proof/15% ABV)[63][non-primary source needed]

Distillery

[edit]

The Jack Daniel Distillery in Lynchburg is situated in and around a hollow known as "Stillhouse Hollow" or "Jack Daniel's Hollow", where a spring flows from a cave at the base of a limestone cliff. The limestone removes iron from the water, making it ideal for distilling whiskey (water heavy in iron gives whiskey a bad taste).[6] The spring feeds into nearby East Fork Mulberry Creek, which is part of the Elk River watershed. Some 1.9 million barrels containing the aging whiskey are stored in several dozen barrelhouses, some of which adorn the adjacent hilltops and are visible throughout Lynchburg.[46]

The distillery is a major tourist attraction, drawing more than a quarter of a million visitors annually.[46] The visitor center, dedicated in June 2000, contains memorabilia related to the distillery and a gift shop. Paid tours of the distillery are conducted several times per day and a premium sampling tour is also offered.[64]

In February 2016 a $140 million expansion was announced for the distillery, including a plan to expand the visitors center and add two more barrel houses.[65]

Mixed Drinks

[edit]- Jack Daniel's is the alcoholic component of "Jack and Coke", a common variant of a highball also known as Bourbon and Coke.[66] In January 2016, Food and Beverage magazine dubbed the drink "The Lemmy" in honor of singer and bassist from the band Motörhead, Lemmy Kilmister, who died in December 2015, as it was his regular drink.[67]

- Jack Daniel's is also the alcoholic component of "Lynchburg Lemonade".[68]

- Jack Daniel's is a common choice for the Tennessee Whiskey component of the "Three Wise Men".

Gallery

[edit]-

Grain mill at Jack Daniel's Distillery

-

Whiskey barrels in the distillery

-

Inside the barrels

Cultural references

[edit]

Notable drinkers of Jack Daniel's

[edit]- Frank Sinatra was a Jack Daniel's drinker. He was buried with a bottle of Jack Daniel's in 1998.[69]

- Lemmy Kilmister of Motörhead cited Jack Daniel's as his drink of choice. Often in media appearances he would be seen drinking Jack Daniel's and Coke, and he reportedly drank a whole bottle every day for 38 years.[70]

- Eric Church, Country singer/songwriter, wrote a song called Jack Daniels on his Chief album. Later he partnered with Jack Daniels and created Eric Church Single Barrel Select.[71]

Cover art

[edit]- The cover of Mel McDaniel’s 1980 album I'm Countryfied featured a design based on the label of Jack Daniel's whiskey.

- The cover of Patrick Wensink's book Broken Piano for President featured a design based on the label of Jack Daniel's whiskey, which resulted in a cease-and-desist letter from the company.[72] However, the whiskey company said it could be done upon the book's next reprinting and it would compensate the author if he chose to comply during the current run.[73]

- The cover of The Dirt: Confessions of the World's Most Notorious Rock Band, an autobiography collectively written by the members of the rock band Mötley Crüe, includes a bottle design based on that of Jack Daniel's whiskey.

- The Charlie Daniels Band album Way Down Yonder depicts bottles of Jack Daniel's on its cover art.

See also

[edit]- Outline of whisky

- List of historic whisky distilleries

- Major competitor brands

- George Dickel, the other major brand of Tennessee whiskey, produced by Diageo PLC (introduced in 1964)

- Jim Beam, the largest-selling Kentucky bourbon whiskey, produced by Beam Suntory (introduced in 1933)

- Evan Williams, another high-selling brand of Kentucky bourbon whiskey, produced by Heaven Hill (introduced in 1957)

- Sister brands produced by Brown–Forman

- Old Forester, a historically important brand of Kentucky bourbon whiskey (introduced in 1870)

- Woodford Reserve, a newer premium brand of Kentucky bourbon whiskey (introduced in 1996)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Brown-Forman Reports Fiscal 2017 Results; Expects Stronger Trends to Continue in Fiscal 2018". Brown–Forman Corporation (official website). June 7, 2017. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ^ Williams III, G. Chambers (February 11, 2016). "Jack Daniel expanding distillery, adding jobs in Lynchburg, Tenn". Knoxville News Sentinel. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Tennessee Myths and Legends". Tennessee State Library and Archives. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ a b "People" section of Jack Daniel's website. Retrieved: March 20, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Book Discussion: Blood & Whiskey: The Life and Times of Jack Daniel. C-SPAN.

- ^ a b c d e f Jeanne Ridgway Bigger, "Jack Daniel's Distillery and Lynchburg: A Visit to Moore County, Tennessee", Tennessee Historical Quarterly, Vol. 31, No. 1 (Spring 1972), pp. 3-21.

- ^ Jasper "Jack" Newton Daniel. Archived April 7, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Krass, Peter (2004). Blood and whiskey: the life and times of Jack Daniel. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-27392-9. (page 7 saying "after he was born in 1849", and page 19 saying "By the time Jack was born in January 1849, ...")

- ^ a b Floyd, Tiffany. "Nathan "Nearest" Green". Whiskey University. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- ^ Randle, Aaron (June 1, 2023). "How an Enslaved Man Helped Jack Daniel Develop His Famous Whiskey". HISTORY. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- ^ Carroll Van West, Megan Dobbs, and Brian Eades, National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form for Lynchburg Historic District, Southern Places Database (MTSU Center for Historic Preservation), 1995.

- ^ Jack Daniel's Legacy, Ben A Green, Shelbyville, Tennessee, 1967

- ^ Holman, Robert (September 3, 2015). "Old Motlow home getting more than a facelift". The Tullahoma News. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ Motlow v. State, Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of Tennessee, Vol. 125 (1912), pp. 557-594.

- ^ "Can't Make Whiskey There", The New York Sun, March 17, 1912, p. 1.

- ^ Freeth, N. (2005). Made in America: from Levis to Barbie to Google. St. Paul, MN: MBI.

- ^ a b "Jack Daniel Distillery". The Whisky Guide. Archived from the original on January 9, 2010. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ "Brown-Forman Unveils Plans to Celebrate 75th Anniversary of End of Prohibition". RedOrbit. June 16, 2008. Archived from the original on September 10, 2012. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Lem Motlow Archived June 4, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Jack Daniel's website. Retrieved: March 20, 2014.

- ^ "Slight Change of Recipe". Time. August 5, 1966. Archived from the original on February 22, 2008. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ^ Adetunji, Jo (June 16, 2012). "Welshman claims to have found original Jack Daniel's whiskey recipe". The Guardian. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ "Drinkers object to Jack Daniel's watering whiskey down". USA Today. September 29, 2004. Retrieved March 9, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "A Legacy Betrayed" Archived January 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Modern Drunkard Magazine, 2002.

- ^ a b c d "Weaker Jack Daniel's Becomes Spirits Strongman", Advertising Age, May 16, 2005.

- ^ Stengel, Jim. "Jack Daniel's Secret: The History of the World's Most Famous Whiskey". The Atlantic. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

- ^ Owen Bellwood (June 26, 2018). "Top 10 best-selling world whisk(e)y brands". thespiritbusiness.com. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ^ "Diageo tops IWSR's brand rankings". Business Standard. September 5, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "The IWSR Real 100 Spirits Brands Worldwide – The Facts". just-drinks.com. June 27, 2017. Archived from the original on May 17, 2018. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ^ "The Power 100 Spirits & Wine". RankingTheBrands. Intangible Business. 2014. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "The Power 100 Spirits & Wine | 2015". rankingthebrands.com. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ^ Jack Daniel's set to exit V8 Supercars Speedcafe November 25, 2015

- ^ "Jack Daniel's will end NASCAR sponsorship; Company backed a team for 5 years".[dead link] The Tennessean, September 22, 2009.

- ^ Flicker, Jonah (September 14, 2022). "Jack Daniel's Will Sponsor McLaren's Formula 1 Team Next Year". Robb Report.

- ^ Flicker, Jonah (April 27, 2023). "Jack Daniel's and McLaren's F1 Team Tease Their First Limited Edition Whiskey Collab". Robb Report. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ Jogia, Saajan (November 16, 2023). "F1 News: McLaren Adds The Jack Daniel's Touch On Its Cars For The Las Vegas GP". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ "Nearest Green: Jack Daniel's First Master Distiller". May 25, 2017.

- ^ "The story of Jack Daniel's". May 25, 2017.

- ^ a b Hevesi, Dennis (August 10, 2009). "Jimmy Bedford, Guardian of Jack Daniel's, Dies at 69". The New York Times. Retrieved August 11, 2009.

- ^ "Former Jack Daniel's master distiller dies at 69". WRCB. August 7, 2009. Retrieved August 11, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Jack Daniel's master distiller stepping down after 12 years". AP NEWS. September 3, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ "Ex-Jack Daniel's distiller to make new whiskey in Tennessee". AP NEWS. April 20, 2021. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ "Chris Fletcher: Jack Daniel's New Master Distiller" (Press release). Jack Daniel's. October 7, 2020.

- ^ JeePee. "The Jack Daniel's Tennessee Squire Association".[self-published source?]

- ^ "Tennessee Squires Association".

- ^ Waymack, Mark H.; Harris, James (August 1995). The Book of Classic American Whiskeys. p. 188. ISBN 9780812693065. OL 784496M.

- ^ a b c d Beth Haynes, "HomeGrown: Jack Daniel's Distillery Archived March 22, 2014, at archive.today", WBIR.com, December 4, 2012. Retrieved: March 21, 2014.

- ^ Axelrod, Alan (2003). The complete idiot's guide to mixing drinks. Indianapolis, IN: Alpha Books. ISBN 0-02-864468-9. LCCN 2002117443.

- ^ "NAFTA - Chapter 3 - Annex 307.3 to Annex 315". www.sice.oas.org.

- ^ "Canada Food and Drug regulations, C.R.C. C.870, provision B.02.022.1". Archived from the original on January 6, 2011. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ^ Jack Daniel's on Whisky.com

- ^ "The Straightbourbon FAQ". Straight Bourbon.com. Archived from the original on April 17, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2012.

- ^ McCarley, Daniel J. (2021). Jack Daniel's Bottle Collector's Guide - Volume 2. Daniel J McCarley. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-0578898988.

- ^ Schelzig, Erik (July 7, 2014). "Jack Daniel's opens Alabama barrel making facility". Montgomery Advertiser. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ Esterl, Mike (March 18, 2014). "Jack Daniels Faces Whiskey Rebellion". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 19, 2014. Retrieved March 18, 2014.

- ^ a b c Zandona, Eric. "Tennessee Whiskey Gets a Legal Definition". EZdrinking. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ "Public Chapter No. 341" (PDF). State of Tennessee. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ^ Robert Holman, "Jack Daniel Denounces Barrel Legislation", The Tullahoma News, March 18, 2014.

- ^ Roberts, John (October 21, 2011). "Jack Daniel's Faces More Taxes From Cash-Strapped Hometown in Tennessee". Fox News. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ Ghianni, Tim (November 22, 2011). "Jack Daniel's wins battle over whiskey barrel tax". Reuters. Reuters. Retrieved September 7, 2014.

- ^ "Tennessee Jurisdictions Allowing Liquor Sales" (PDF). Tennessee Alcoholic Beverage Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 7, 2014. Retrieved September 8, 2014.

- ^ The Tennessee General Assembly passed a 1994 special act for selling commemorative decanters containing Jack Daniel's Tennessee Whiskey on January 2, 1995.

- ^ "Jack Daniel's Launches Single Barrel Rye". Cocktail Enthusiast. February 10, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ "Verify Age | Jack Daniel's Tennessee Whiskey". Archived from the original on September 20, 2013. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ Jack Daniel's Tours, Jack Daniel's official website. Retrieved: December 21, 2017.

- ^ Lind, JR (February 10, 2016). "Jack Daniel's announces $140M expansion". Nashville Post. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ Walker, Tracy. Walker Archived May 10, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. "It's clear that brown spirits have gained momentum, particularly the Tennessee whiskey segment." Retrieved February 1, 2007.

- ^ "The Lemmy". Food & Beverage Magazine. January 12, 2016. Archived from the original on December 5, 2020. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- ^ "Jack Daniel Recipes". Archived from the original on October 19, 2011. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

- ^ "How Frank Sinatra Really Met Jack Daniel's". Globe Newswire. October 9, 2020.

- ^ Hartmann, Graham (October 15, 2013). "Motörhead's Lemmy Kilmister Talks Health, Smoking, Drinking and Death". Loudwire. Retrieved March 20, 2014.

- ^ "Eric Church Single Barrel Select". Jack Daniel's. July 10, 2020.

- ^ Jack Daniel's Classy Book Cover Cease-And-Desist Letter For Patrick Wensink's 'Broken Piano For President' Huffington Post July 23, 2012

- ^ O'Reilly, Terry (January 5, 2017). "The Crazy World of Trademarks". Under the Influence. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- McCarley, Daniel J (2011). Jack Daniel's: The Unofficial Bottle Collector's Guide - Volume 1. ISBN 978-0-578-09069-6.

External links

[edit]- Brown–Forman brands

- Tennessee whiskey

- Distilleries in Tennessee

- American brands

- Tennessee cuisine

- Tourist attractions in Tennessee

- Tourist attractions in Moore County, Tennessee

- National Register of Historic Places in Moore County, Tennessee

- 1866 establishments in Tennessee

- Industrial buildings and structures on the National Register of Historic Places in Tennessee

- Moore County, Tennessee

- Lynchburg, Tennessee