Taiwan Miracle

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2018) |

| Taiwan Miracle | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 臺灣奇蹟 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Taiwan Economic Miracle | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 臺灣經濟奇蹟 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

The Taiwan Miracle (Chinese: 臺灣奇蹟; pinyin: Táiwān Qíjī; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Tâi-oân Kî-chek) or Taiwan Economic Miracle refers to Taiwan's rapid economic development to a developed, high-income country during the latter half of the twentieth century. [1]

As it developed alongside South Korea, Singapore, and Hong Kong, Taiwan became known as one of the "Four Asian Tigers". Taiwan was the first developing country to adopt an export-oriented trade strategy after World War II.[2]

Background

After a period of hyperinflation in the late 1940s when the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China military regime of Chen Yi overprinted the Taiwanese dollar against the previous Taiwanese yen in the Japanese era, it became clear that a new and stable currency was needed. Along with the $4 billion in financial aid and soft credit[citation needed] provided by the US (as well as the indirect economic stimulus of US food and military aid) over the 1945–1965 period, Taiwan had the necessary capital to restart its economy. Further, the Kuomintang government instituted many laws and land reforms that it had never effectively enacted on mainland China.[citation needed]

A land reform law, inspired by the same one that the Americans were enacting in occupied Japan, removed the landlord class (similar to what happened in Japan), and created a higher number of peasants who, with the help of the state, increased the agricultural output dramatically. This was the first excedent accumulation[clarification needed] source.[3] It inverted capital creation, and liberated the agricultural workforce to work in the urban sectors. However, the government imposed on the peasants an unequal exchange with the industrial economy, with credit and fertilizer controls and a non monetary exchange to trade agrarian products (machinery) for rice. With the control of the banks (at the time, being the property of the government), and import licenses, the state oriented the Taiwanese economy to import substitution industrialization, creating initial capitalism in a fully protected market.

It also, with the help of USAID, created a massive industrial infrastructure, communications, and developed the educational system.[4] Several government bodies were created and four-year plans were also enacted. Between 1952 and 1982, economic growth was on average 8.7%, and between 1983 and 1986 at 6.9%. The gross national product grew by 360% between 1965 and 1986. The percentage of global exports was over 2% in 1986, over other recently industrialized countries, and the global industrial production output grew a further 680% between 1965 and 1986. The social gap between the rich and the poor fell (Gini: 0.558 in 1953, 0.303 in 1980), even lower than some Western European countries, but it grew a little in the 80's. Health care, education, and quality of life also improved.[5] The flexibility of the productive system and the industrial structure meant that Taiwanese companies had more chances to adapt themselves to the changing international situation and the global economy.[citation needed]

The economist S. C. Tsiang played an influential role in shifting towards an export-oriented trade strategy.[2] In 1954, he called for Taiwan to deal with its chronic shortage of foreign exchange by increasing exports rather than reduce imports.[2] In 1958, the policymaker K. Y. Yin pushed for the adoption of Tsiang's ideas.[2]

In 1959, a 19-point program of Economic and Financial Reform, liberalized market controls, stimulated exports and designed a strategy to attract foreign companies and foreign capital. An exports processing area was created in Kaohsiung and in 1964, General Instruments pioneered in externalizing electronic assembly in Taiwan. Japanese companies moved in, reaping the benefits of low salaries, the lack of environmental laws and controls, a well-educated and capable workforce, and the support of the government.[citation needed] But the nucleus of the industrial structure was national, and it was composed by a large number of small and medium-sized enterprises, created within families with the family savings, and savings cooperatives nets called hui (Chinese: 會; pinyin: Huì; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Hōe; Pha̍k-fa-sṳ: Fi). They had the support of the government in the form of subsidies and credits loaned by the banks.

Most of these societies appeared for the first time in rural zones near metropolitan areas, where families shared work (in the parcels they owned and in the industrial workshops at the same time). For instance, in 1989 in Changhua, small enterprises produced almost 50% of the world's umbrellas.[citation needed] The State attracted foreign companies in order to obtain more capital and to get access to foreign markets, but the big foreign companies got contracts with this huge net of small sized, familiar and national companies, which were a very important percentage of the industrial output.

Foreign investment never represented an important component in the Taiwanese economy, with the notable exception of the electronic market. For instance, in 1981, direct foreign investment was a mere 2% of the GNP, foreign companies employed 4.8% of the total workforce, their production was 13.9% of the total production and their exports were 25.6% of nationwide exports.[citation needed] Access to the global markets was facilitated by the Japanese companies and by the American importers, who wanted a direct relationship with the Taiwanese brands. No big multinational corporations were created (like in Singapore), or huge national conglomerates (like South Korean chaebols), but some industrial groups, with the support of the government, grew, and became in the 90's huge companies totally internationalized. Most of the development was thanks to the flexibility of family businesses which produced for foreign traders established in Taiwan and for international trade nets with the help of intermediaries.

After retreating to Taiwan, Chiang learned from his mistakes and failures in the mainland and blamed them for failing to pursue Sun Yat-sen's ideals of Tridemism and welfarism. Chiang's land reform more than doubled the land ownership of Taiwanese farmers. It removed the rent burdens on them, with former land owners using the government compensation to become the new capitalist class. He promoted a mixed economy of state and private ownership with economic planning. Chiang also promoted a 9-years compulsory education and the importance of science in Taiwanese education and values. These measures generated great success with consistent and strong growth and the stabilization of inflation.[6]

Era of globalization

In the 1970s, protectionism was on the rise, and the United Nations switched recognition from the government of the Republic of China to the government of the People's Republic of China as the sole legitimate representative of mainland China. It was expelled by General Assembly Resolution 2758 and replaced in all UN organs with the PRC. The Kuomintang began a process of enhancement and modernization of the industry, mainly in high technology (such as microelectronics, personal computers and peripherals). One of the biggest and most successful Technology Parks was built in Hsinchu, near Taipei.[citation needed]

Many Taiwanese brands became important suppliers of worldwide known firms such as DEC or IBM, while others established branches in Silicon Valley and other places inside the United States and became known.[citation needed] The government also recommended the textile and clothing industries to enhance the quality and value of their products to avoid restrictive import quotas, usually measured in volume. The decade also saw the beginnings of a genuinely independent union movement after decades of repression. Some significant events occurred in 1977, which gave the new unions a boost.[citation needed]

One was the formation of an independent union at the Far East Textile Company after a two-year effort discredited the former management-controlled union. This was the first union that existed independently of the Kuomintang in Taiwan's post-war history (although the Kuomintang retained a minority membership on its committee). Rather than prevailing upon the state to use martial law to smash the union, the management adopted the more cautious approach of buying workers' votes at election times. However, such attempts repeatedly failed and, by 1986, all of the elected leaders were genuine unionists.[3] Another, and, historically, the most important, was the now called "Zhongli incident".

In the 1980s, Taiwan had become an economic power, with a mature and diversified economy, solid presence in international markets and huge foreign exchange reserves.[7] Its companies were able to go abroad, internationalize their production, investing massively in Asia (mainly in People's Republic of China) and in other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, mainly in the United States.

Higher salaries and better organized trade unions in Taiwan, together with the reduction of the Taiwanese export quotas meant that the bigger Taiwanese companies moved their production to China and Southeast Asia. The civil society in a now developed country, wanted democracy, and the rejection of the KMT dictatorship grew larger.[8] A major step occurred when Lee Teng-hui, a native from Taiwan, became President, and the KMT started a new path searching for democratic legitimacy.

Two aspects must be remembered: the KMT was on the center of the structure and controlled the process, and that the structure was a net made of relations between the enterprises, between the enterprises and the State, between the enterprises and the global market thanks to trade companies and the international economic exchanges.[9] Native Taiwanese were largely excluded from the mainlanders dominated government, so many went into the business world.

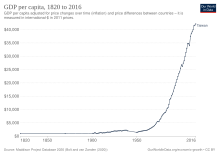

In 1952, Taiwan had a per capita gross national product (GNP) of $170, placing the island's economy squarely between Zaire and Congo.[citation needed] But, by 2018 Taiwan's per capita GNP, adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP), had soared to $53,074, around or above some developed West European economies and Japan.[citation needed]

According to economist Paul Krugman, the rapid growth was made possible by increases in capital and labor but not an increase in efficiency. In other words, the savings rate increased and work hours were lengthened, and many more people, such as women, entered the work force.[10][irrelevant citation]

Dwight Perkins and others cite certain methodological flaws in Krugman and Alwyn Young's research, and suggest that much of Taiwan's growth can be attributed to increases in productivity. These productivity boosts were achieved through land reform, structural change (urbanization and industrialization), and an economic policy of export promotion rather than import substitution.[citation needed]

Future growth

Economic growth has become much more modest since the late 1990s. A key factor to understand this new environment is the rise of China, offering the same conditions that made possible, 40 years ago, the Taiwan Miracle (a quiet political and social environment, cheap and educated workers, absence of independent trade unions).[citation needed]

One major difference with Taiwan is the focus on English education. Mirroring Hong Kong and Singapore, the ultimate goal is to become a country fluent in three languages[citation needed] (Taiwanese; Mandarin, the national language of China, and Taiwan; and English, becoming a bridge between East and West).

According to western financial markets, consolidation of the financial sector remains a concern as it continues at a slow pace, with the market split so small that no bank controls more than 10% of the market, and the Taiwanese government is obligated, by the WTO accession treaty, to open this sector between 2005 and 2008.[11]

However, many financial analysts estimate such concerns are based upon mirror-imaging of the Western model and do not take into account the already proven Asian Tiger model. Yet, recently,[when?] credit card debt has become a major problem, as the ROC does not have an individual bankruptcy law.[citation needed]

Generally, transportation infrastructure is very good and continues to be improved, mainly in the west side of the island. Many infrastructure improvements are currently being pursued, such as the first rapid transit lines opening in Kaohsiung in 2008 and a doubling in size of Taipei's rapid transit system by 2013 now underway; the country's highways are very highly developed and in good maintenance and continue to be expanded, especially on the less developed and less populated east coast, and a controversial electronic toll system has recently[when?] been implemented.

The completion of the Taiwan High Speed Rail service connecting all major cities on the western coast, from Taipei to Kaohsiung is considered to be a major addition to Taiwan's transportation infrastructure. The ROC government has chosen to raise private financing in the building of these projects, going the build-operate-transfer route, but significant public financing has still been required and several scandals have been uncovered. Nevertheless, it is hoped that the completion of these projects will be a big economic stimulus, just as the subway in Taipei has revived the real estate market there.[citation needed]

Technology sector

Taiwan continues to rely heavily on its technology sector, a specialist in manufacturing outsourcing. Recent developments include moving up the food chain in brand building and design. LCD manufacturing and LED lights are two newer sectors in which Taiwanese companies are moving. Taiwan also wants to move into the biotechnology sector, the creation of fluorescent pet fish and a research-useful fluorescent pig[12] being two examples. Taiwan is also a leading grower of orchids.

Taiwan's information technology (IT) and electronics sector has been responsible for a vast supply of products since the 1980s. The Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) was created in the 1973 to meet new demands from the burgeoning tech industry. This led to start-up companies like Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) and the construction of the Hsinchu Science and Industrial Park (HSP), which includes around 520 high-tech companies and 150,000 employees.[13] By 2015, a bulk of the global market share of motherboards (89.9 percent), Cable CPE (84.5 percent), and Notebook PCs (83.5 percent) comprise both offshore and domestic production. It placed second in producing Transistor-Liquid Crystal Display (TFT-LCD panels) (41.4 percent) and third for LCD monitors (27 percent) and LED (19 percent).[14] Nonetheless, Taiwan is still heavily reliant on offshore capital and technologies, importing up to US$25 billion worth of machinery and electrical equipment from Mainland China, US$16 billion from Japan, and US$10 billion from the U.S.[14]

In fact, the TFT-LCD industry in Taiwan grew primarily from state-guided personnel recruitment from Japan and inter-firm technology diffusion to fend off Korean competitors. This is due to Taiwan's unique trend of export-oriented small and medium enterprises (SME) – a direct result of domestic-market prioritization by state-owned enterprises (SOE) in its formative years.[15] While the development of SMEs allowed better market adaptability and inter-firm partnerships, most companies in Taiwan remained original equipment manufacturers (OEM) and did not – other than firms like Acer and Asus – expand to original design manufacturing (OBM).[16] These SMEs provide "incremental innovation" with regard to industrial manufacturing but do not, according to Dieter Ernst of the East–West Centre, a think-tank in Honolulu, surpass the "commodity trap", which stifles investment in branding and R&D projects.[17]

The Taiwanese president Tsai Ing-wen, of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) enacted policies building on the continued global influence of Taiwan's IT industry. To revamp and reinvigorate Taiwan's slowing economy, her "5+2" innovative industries initiative aims to boost key sectors such as biotech, sustainable energy, national defense, smart machinery, and the "Asian Silicon Valley" project.[18] President Tsai herself was the chairperson for TaiMed Biologics, a state-led start-up company for biopharmaceutical development with Morris Chang, the CEO of TSMC, as an external adviser.[19] On 10 November 2016, the Executive Yuan formally endorsed a biomedical promotion plan with a budget of NT$10.94 billion (US$346.32 million).[20]

At the opening ceremony for the Asia Silicon Valley Development Agency (ASVDA) in December 2016, Vice President Chen Chien-jen emphasized the increasing importance of enhancing not only local R&D capabilities, but also appealing to foreign investment.[21] For example, the HSP now focuses 40 percent of its total workforce on "R&D and technology development".[13] R&D expenditures have been gradually increasing: In 2006, it amounted to NT$307 billion, but it increased to NT$483.5 billion (US$16 billion) in 2014, approximately 3 percent of the GDP.[22] The World Economic Forum's Global Competitiveness Report 2017–2018 profiled up to 140 countries, listing Taiwan as 16th place in university-industry collaboration in R&D, 10th place in company spending on R&D, and 22nd place in capacity for innovation.[23] Approved overseas Chinese and foreign investment totaled US$11 billion[24] in 2016, a massive increase from US$4.8 billion in 2015.[24] However, the Investment Commission of the Ministry of Economic Affairs' (MOEAIC) monthly report from October 2017 estimated a decline in total foreign direct investment (between January and October 2017) to US$5.5 billion, which is a 46.09 percent decrease from the same time period of 2016 (US$10.3 billion).[25]

Cross-strait relations

Debate on opening "Three Links" with the People's Republic of China were completed in 2008, with the security risk of economic dependence on PR China being the biggest barrier. By decreasing transportation costs, it was hoped that more money will be repatriated to Taiwan and that businesses will be able to keep operations centers in Taiwan while moving manufacturing and other facilities to mainland China.

A law forbidding any firm investing in the PR China more than 40% of its total assets on the mainland was dropped in June 2008, when the new Kuomintang government relaxed the rules to invest in the PR China. Dialogue through semi-official organisations (the SEF and the ARATS) reopened on 12 June 2008 on the basis of the 1992 Consensus, with the first meeting held in Beijing. Taiwan hopes to become a major operations center in East Asia.

Regional free trade agreements

While China already has international free trade agreements (FTA) with numerous countries through bilateral relations and regional organizations, the "Beijing factor" has led to the deliberate isolation of Taiwan from potential FTAs.[26] In signing the Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA) with China on 29 June 2010 – which permitted trade liberalization and an "early harvest" list of tariff cuts[27] – former president Ma Ying-jeou wanted to not only affirm a stable economic relationship with China, but also to assuage its antagonism towards Taiwan's involvement in other FTAs. Taiwan later signed FTAs with two founding members of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2013: New Zealand (ANZTEC)[28] and Singapore (ASTEP).[29] Exports to Singapore increased 5.6 percent between 2013 and 2014, but decreased 22 percent by 2016.[24]

In 2013, a follow-up bilateral trade agreement to the ECFA, the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement (CSSTA), faced large student-led demonstrations – the Sunflower Movement – in Taipei and an occupation of the Legislative Yuan. The opposition contended[30] that the trade pact would hinder the competency of SMEs, which encompassed 97.73 percent of total enterprises in Taiwan in 2016.[31] The TPP, on the other hand, still presents an opportunity for Taiwan. After the APEC economic leaders' meeting in November 2017, President Tsai expressed deep support for the advancements made regarding the TPP[32] – given that U.S. President Donald Trump pulled out of the trade deal earlier in the year.[33] President Tsai has also promoted the "New Southbound Policy", mirroring the "go south" policies upheld by former presidents Lee Teng-hui in 1993 and Chen Shui-Bian in 2002, focusing on partners in the Asia-Pacific region such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Australia and New Zealand.[34]

See also

References

- ^ The phrase was apparently first used in Gold, Thomas B. (1985). State and Society in the Taiwan Miracle. Armonk, N.Y.: Armonk, N.Y. : M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 9781317459408. Archived from the original on 2023-03-28. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ a b c d Irwin, Douglas A. (2023). "Economic ideas and Taiwan's shift to export promotion in the 1950s". The World Economy. 46 (4): 969–990. doi:10.1111/twec.13395. ISSN 0378-5920. S2CID 256974921. Archived from the original on 2023-02-26. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- ^ a b "The Labour Movement in Taiwan". 21 September 2004. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ JACOBY, NEIL H. (1966). AN EVALUATION OF U. S. ECONOMIC AID TO FREE CHINA, 1951-1965 (PDF). BUREAU FOR THE FAR EAST AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT. p. 20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-03-28. Retrieved 2023-02-16.

- ^ "The Story of Taiwan, Economy". Archived from the original on 2 February 2010.

- ^ Chinese University of Hong Kong [dead link]

- ^ Foreign Exchange Reserves, Taiwan and other major countries Archived 20 September 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Story of Taiwan, Politics". Archived from the original on 2006-12-30. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ Manuel Castells: Information Age, Third Volume, The End of The Millennium, page 303, Alianza Editorial, 1998

- ^ "Paul Krugman". The Myth of Asia's Miracle. Nov 1994. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ "Trade and Investment Opportunities Presented by Taiwan's Accession to the World Trade Organization". Archived from the original on 2012-02-10. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ Hsiao, F. S. H.; Lian, W. S.; Lin, S. P.; Lin, C. J.; Lin, Y. S.; Cheng, E. C. H.; Liu, C. W.; Cheng, C. C.; Cheng, P. H.; Ding, S. T.; Lee, K. H.; Kuo, T. F.; Cheng, C. F.; Cheng, W. T. K.; Wu, S. C. (2011). "Toward an ideal animal model to trace donor cell fates after stem cell therapy: Production of stably labeled multipotent mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow of transgenic pigs harboring enhanced green fluorescence protein gene". Journal of Animal Science. 89 (11): 3460–3472. doi:10.2527/jas.2011-3889. PMID 21705633.

- ^ a b 投資組投資服務科 (10 March 2017). "Introduction". www.sipa.gov.tw. Archived from the original on 16 December 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ a b Council, National Development (26 May 2015). "National Development Council-Taiwan Statistical Data Book". National Development Council. Archived from the original on 16 December 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ Wu, Yongping (2005). A Political Explanation of Economic Growth. Harvard University Asia Center. p. 46.

- ^ CHEVALÉRIAS, PHILIPPE (2010). "Taiwanese Economy After the Miracle: An Industry in Restructuration, StructuralWeaknesses and the Challenge of China". China Perspectives. 3: 40. Archived from the original on 2019-06-15. Retrieved 2019-08-05.

- ^ "Hybrid vigour: Taiwan's tech firms are conquering the world—and turning Chinese". The Economist. 27 May 2010. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ Dittmer, Lowell (2017). Taiwan and China: Fitful Embrace. Oakland, California: University of California Press. p. 153.

- ^ Wong, Joseph (2011). Betting on Biotech: Innovation and the Limits of Asia's Developmental State. U.S.A.: Cornell University Press.

- ^ "Biomedical plan fast-tracks Taiwan for top spot in Asia - New Southbound Policy Portal". New Southbound Policy. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "Asia Silicon Valley Development Agency launches in Taoyuan". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China. 27 December 2016. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ Council, National Development (9 November 2016). "National Development Council-Taiwan Statistical Data Book". National Development Council. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ Schwab, Klaus. "The Global Competitiveness Report 2017–2018" (PDF). World Economic Forum. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-09-29. Retrieved 2017-12-08.

- ^ a b c "Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of China 2016" (PDF). Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, Executive Yuan, Republic of China. October 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-09-17. Retrieved 2017-12-08.

- ^ "INVESTMENT COMMISSION, MOEA -". www.moeaic.gov.tw. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ Cheng, T.J. (July 2015). "Global Opportunities, Local and Transnational Politics: Taiwan's Bid for FTAs". American Journal of Chinese Studies. 22: 145.

- ^ Bush, Richard C. (2013). Uncharted Strait: The Future of China-Taiwan Relations. Brookings Institution Press. p. 50.

- ^ "ANZTEC - Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China (Taiwan) 中華民國外交部 - 全球資訊網英文網". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China (Taiwan) 中華民國外交部 - 全球資訊網英文網. Archived from the original on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "The Republic of China (Taiwan) and the Republic of Singapore sign an economic partnership agreement". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China (Taiwan). 11 July 2014. Archived from the original on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ Hsu, Jenny W. (30 March 2014). "Thousands Protest Taiwan's Trade Pact With China". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "2017 White Paper on Small and Medium Enterprises in Taiwan". Small and Medium Enterprise Administration, Ministry of Economic Affairs. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017.

- ^ "Tsai praises TPP progress at APEC". Taipei Times. 14 November 2017. Archived from the original on 2 December 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "Trump withdraws from TPP trade deal". BBC News. 2017. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "New Southbound Policy: an Introduction (2017.02.28) - New Southbound Policy Portal". New Southbound Policy. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

External links

- Official Website of Taiwan for WTO affairs, Documents

- Official Website of Taiwan for WTO affairs

- Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu (Chinese Taipei) and the WTO

- Cross-Strait Relations between China and Taiwan

- A New Era in Cross-Strait Relations? Taiwan and China in the WTO

- China's Economic Leverage and Taiwan's Security Concerns with Respect to Cross-Strait Economic Relations