Swatow ware

Swatow ware or Zhangzhou ware is a loose grouping of mainly late Ming dynasty Chinese export porcelain wares initially intended for the Southeast Asian market. The traditional name in the West arose because Swatow, or present-day Shantou, was the South Chinese port in Guangdong province from which the wares were thought to have been shipped. The many kilns were probably located all over the coastal region,[2] but mostly near Zhangzhou, Pinghe County, Fujian, where several were excavated in the mid-1990s, which has clarified matters considerably.[3]

Many authorities now prefer to call the wares Zhangzhou ware, as it seems that Swatow did not become an important export port until the 19th century, and the wares were actually probably exported from Yuegang, now Haicheng in Longhai City, Zhangzhou.[4] The precise dates for the beginning and ending of production remain uncertain,[5] but the evidence from archaeology suggests production between about 1575–1650, though an earlier start has been proposed. The peak levels of production may have ended around 1620.[6]

Compared to contemporary Jingdezhen porcelain, Swatow ware is generally coarse, crudely potted and often under-fired. Decoration in underglaze blue and white using cobalt is the most common, and was probably the only type of decoration at first, but there are many polychrome wares, using red, green, turquoise, black and yellow overglaze enamels. Underglaze blue decoration had been common in Chinese ceramics for over two centuries, but polychrome enamels had been relatively unusual before this period.[7] The pieces are mostly "large open forms such as dishes, painted with sketchy designs over the glaze in red, green, turquoise and black enamels".[8] On the other hand, the "drawing has a spontaneity not found in the central tradition" of finer wares.[9]

While "Swatow ware" is typically reserved for pieces with the characteristic styles of decoration, "Zhangzhou ware" also covers other types of wares made in the same kilns, for export or not, including large stoneware storage jars, whitewares,[10] and a few figurines of the blanc de Chine type.[11]

Characteristics

[edit]

The most common subjects are birds in flight or at rest in or by water, and flowers. Animals, especially deer, set in a landscape are also common, as main subjects or in medallions in the border. Human figures are usually shown as staffage in landscapes, especially manning boats, but sometimes as a main subject. Other motifs are sea-monsters and dragons, both oddly-shaped. Some dishes have Islamic inscriptions in Arabic, intended for South East Asian Muslims rather than those further west. Some dishes show European ships, and represent Western ship's compasses. The designs show awareness of contemporary Jingdezhen porcelain, but at a considerable distance. Smaller numbers of pieces, often undecorated, are in a range of other background colours, especially blues and browns, usually achieved by slips, but also by applying coloured glazes all over.[12]

The pieces very often have grit from the kiln on the glaze at the foot, indicating rather careless making.[13] They were fired in dragon kilns of various designs, and the numerous potteries were small concerns, far removed from the industrial scale of Jingdezhen. Pieces were mostly wheel-thrown, but moulds were also used to form pieces.[14]

The iconography has peculiarities, including the motif of the "split pagoda" where the central scene "is dominated by what resembles a three storey pagoda split in two vertically by a funnel-like strip reserved in white, almost like a volcanic eruption",[15] which has puzzled scholars; there are a number of suggestions as to its meaning.[16] This is now interpreted by some, including the Percival David Foundation and Victoria and Albert Museum, as "the path to the islands of the Immortals" of Chinese mythology, leaping above the building,[17] while others retain an open mind. This design is one of many where the Chinese characters in "debased" seal script make no sense,[18] reflecting illiterate decorators producing for a market that could not read Chinese.[19]

A division of the blue and white wares into three "families" or broad groups has been proposed by Barbara Harrisson: "conservative", "persistent" and "versatile", in chronological order.[20] This classification was further refined by Monique Crick in 2010 into three types of decoration: "Sketchy", "Composed", and "Full "rim-to-rim"".[21] The "Sketchy decoration" group uses "a vigorous, brushed style, painted freehand and spontaneously" by a single artisan.[22] The later groups often use drawing in dark concentrated blue to create the design, which is then overpainted with a lighter wash, in the same style that is often used with black and turquoise in the polychrome enamels. Some of these pieces have visible pin pricks indicating where a stencil was fixed, presumably allowing rapid painting of the wash. The outline would have needed to dry before the wash was applied, suggesting that a number of artisans were involved in different stages of production requiring different levels of skill.[23]

The polychrome enamel wares may not have begun until the start of the 17th century, but then increased rapidly, forming about half of the Swatow pieces from the Binh Thuan wreck, which perhaps sank in 1608.[24] The dishes were given a white slip coating, and fired at the high temperature necessary for porcelain, which would have burnt the coloured enamels. They were then painted before a short second firing at about 800 °C.[25] Common palettes are red, green and (rather less) yellow,[26] and turquoise, red, green and black. The black, mainly used for line-drawing, was actually made from the cobalt used for underglaze blue, in impure and concentrated form.[27]

A relatively rare type is decorated in both underglaze blue and white and overglaze enamels. These pieces were expensive to produce and seem to have been made for the Japanese market.[28] An example can be seen in the wall of dishes illustrated (D5).

Markets

[edit]Asia

[edit]

Almost no examples of Swatow ware have been excavated in China itself, other than at the actual kiln sites, and it seems the wares were, like some other types, entirely made to export. The main markets were the islands of South-East Asia, especially modern Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines, together with Japan,[29] such as those found in Nan'ao One. Other traditional markets for Chinese ceramics such as Korea and Vietnam seem not to be involved; they had already developed more traditional Chinese tastes favouring finely shaped monochrome wares or more delicately decorated styles. The dishes were used for display, and for dining; even royalty sat with guests on mats on the floor, eating communally from several large dishes, as early European visitors reported.[30]

In Japan fragments have been found at prestigious castle and temple sites,[31] and it seems that the rather crude vigour of the decoration appealed to the very sophisticated aesthetic sense of some Japanese tea-masters, leaders of taste at the time. The smaller bowls and jars were more easily utilized in the Japanese tea ceremony and other contexts, and some Japanese pieces imitated Swatow shapes and decoration.[32]

A wreck off the south coast of Vietnam at Binh Thuan carried a cargo whose surviving elements were Swatow ware and cast iron woks; its excavation was published in 2004. The porcelain was about half blue-and-white and half with overglaze enamels, the latter having suffered from the extended immersion in the sea. It may well be the ship recorded as lost at sea in 1608, which the Dutch East India Company (VOC) had arranged to carry a cargo, mainly of Chinese silk, to their station at Johore in modern Malaysia, perhaps intending to trade the ceramics for spices around the Spice Islands. There were thousands of "medium-sized dishes", as well as some blue and white ones up to 42 cm across, and smaller dishes and jars. There were many designs, repeated in batches,[33] much as in modern ceramic output, but with the designs varying from the free and presumably rapid execution.[34]

European

[edit]

European markets were probably much less significant, and the Kraak ware of the same period was probably always sent in greater quantity there. This has many similarities but was all in underglaze blue and white. The Portuguese had traded at Yuegang until expelled in 1548, but were allowed to return from 1567, and in 1577 were allowed to establish a station at Macao. The Santos Palace in Lisbon has a room decorated between 1664 and 1687 with a spectacular angled ceiling covered with Chinese blue and white porcelain dishes; three of these have been identified as Swatow ware.[36]

The Spanish, who were settled at Manila in the Philippines, carried goods including Chinese luxuries between there and New World ports such as Acapulco in the Manila galleon trade. Swatow ware has been recovered from several Spanish sites and wrecks, including Sebastião Rodrigues Soromenho's San Agustin, wrecked in 1595 at Drakes Bay, just north of San Francisco.[37]

The Dutch East India Company, founded in 1602, traded with Indonesia, a major market for the wares. They were not allowed to trade directly with China, and contented themselves with capturing any Portuguese, Spanish and Chinese vessels they could, and probably arranging deliveries to their bases by Chinese ships. From 1624 they had a base on Formosa (modern Taiwan).[38] The rather similar export Kraak porcelain was adapted to suit European tastes, which Swatow ware never seems to have been. Later Swatow wares may have been exported directly to Europe by the Dutch.[39] These European trades have left fragments of Swatow ware at various land sites and wrecks around the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa.[40]

Collections

[edit]The pieces have remained appreciated in their original markets, especially in Indonesia and Japan, where there are several good collections.[41] They were generally not collected by the Chinese and most Western and Chinese museums with good collections of ceramics have sparse holdings.[42] The Dutch Princessehof Ceramics Museum has an exceptional collection of some 170 pieces,[43] with "the most representative range of the type",[44] though in terms of shapes it concentrates on the large dishes.[45] This was originally assembled in Indonesia by a Dutch colonial administrator in the 19th century.

-

A typical design centering on water birds, outline and wash in cobalt blue

-

Dish with Qu'ran verse, prayer, and professions of faith. Such designs were used for courtly welcome ceremonies in the Islamic islands.[46]

-

Foliated dish with landscape

-

Detail of the "split pagoda" motif. A different dish to that shown above; this one from the Princessehof Ceramics Museum

-

Swatow porcelain albarello, in the "Sketchy" blue and white style, before 1600

-

Detail. The "sketchy" dish at lower right has a main human figure.

-

Detail of bird among flowers

-

Another wall of dishes in the Princessehof Ceramics Museum

-

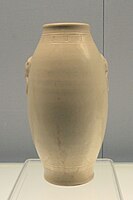

Yellow-glazed olive-shaped vase, for the domestic market

Notes

[edit]- ^ Ströber, 25–26

- ^ Vainker, 145–146

- ^ Ströber, 13; Grove

- ^ Ströber, 12–13; Miksic, 85

- ^ Medley, 234

- ^ Ströber, 53, 35–36

- ^ Ströber, 23–24

- ^ Vainker, 146

- ^ Medley, 235

- ^ Ströber, 15–18

- ^ Figurine of Guanyin, dated 1615

- ^ Grove; Ströber, 16–17, 28; Medley, 233–235; Kerr & Mengoni; Miksic, 44

- ^ Ströber, 14; Medley, 235

- ^ Ströber, 14

- ^ Medley, 235

- ^ Ströber, 30–32 has a full list; Medley, 234–236; Kerr & Mengoni

- ^ British Museum dish, PDF A709; V&A Museum

- ^ Medley, 235

- ^ Kerr & Mengoni

- ^ Ströber, 11, 19; Miksic, 85

- ^ Ströber, 19–21

- ^ Ströber, 19

- ^ Ströber, 20, 25–26

- ^ Ströber, 22

- ^ Ströber, 22

- ^ Ströber, 23

- ^ Ströber, 25

- ^ Ströber, 27

- ^ Ströber, 35

- ^ Ströber, 37–38

- ^ Ströber, 48

- ^ Ströber, 32, 48–52

- ^ Miksic, 44

- ^ Grove

- ^ Ströber, 29, 27

- ^ Ströber, 41; The Porcelain Room in Santos Palace (now the French Embassy in Portugal)

- ^ Ströber, 42, 53–55

- ^ Ströber, 43–45

- ^ Miksic, 85

- ^ Ströber, 46, 53–55

- ^ Ströber, 50

- ^ Ströber, 4, 9–10

- ^ Ströber, 4

- ^ Grove; see gallery

- ^ Ströber, 15

- ^ Ströber, 37

References

[edit]- "Grove" Oxford Art Online, section "Swatow wares" in "China, §VIII, 3.6: Ceramics: Historical development", by Medley, Margaret

- Kerr, Rose, Mengoni, Luisa, Chinese Export Ceramics, pp. 123–124, 2011, Victoria & Albert Museum, ISBN 185177632X, 9781851776320

- Medley, Margaret, The Chinese Potter: A Practical History of Chinese Ceramics, 3rd edition, 1989, Phaidon, ISBN 071482593X

- Miksic, John N., Southeast Asian Ceramics: New Light on Old Pottery, 2009, Editions Didier Millet, ISBN 9814260134, 9789814260138, google books

- Ströber, Eva, The Collection of Zhangzhou Ware at the Princessehof Museum, Leeuwarden, Netherlands, PDF (60 pages)

- Vainker, S. J., Chinese Pottery and Porcelain, 1991, British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714114705

External links

[edit] Media related to Swatow ware at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Swatow ware at Wikimedia Commons- A Handbook of Chinese Ceramics from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

![Dish with Qu'ran verse, prayer, and professions of faith. Such designs were used for courtly welcome ceremonies in the Islamic islands.[46]](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/75/Dish_with_Qu%27ran_verse%2C_prayer%2C_and_professions_of_faith%2C_China%2C_Swatow%2C_17th_century_AD%2C_underglaze_painted_porcelain_-_Aga_Khan_Museum_-_Toronto%2C_Canada_-_DSC06955.jpg/200px-thumbnail.jpg)