Economic stagnation

Economic stagnation is a prolonged period of slow economic growth (traditionally measured in terms of the GDP growth), usually accompanied by high unemployment. Under some definitions, slow means significantly slower than potential growth as estimated by macroeconomists, even though the growth rate may be nominally higher than in other countries not experiencing economic stagnation.

Secular stagnation theory

[edit]The term "secular stagnation" was originally coined by Alvin Hansen in 1938 to "describe what he feared was the fate of the American economy following the Great Depression of the early 1930s: a check to economic progress as investment opportunities were stunted by the closing of the frontier and the collapse of immigration".[1][2] Warnings similar to secular stagnation theory have been issued after all deep recessions, but they usually turned out to be wrong because they underestimated the potential of existing technologies.[3]

Secular stagnation refers to "a condition of negligible or no economic growth in a market-based economy".[4] In this context, the term secular is used in contrast to cyclical or short-term, and suggests a change of fundamental dynamics which would play out only in its own time. Alan Sweezy described the difference: "But, whereas business-cycle theory treats depression as a temporary, though recurring, phenomenon, the theory of secular stagnation brings out the possibility that depression may become the normal condition of the economy."[5]

According to Sweezy, "the idea of secular stagnation runs through much of Keynes General Theory".[5]

Stagnation in the United States

[edit]Historical periods of stagnation in the United States

[edit]- The years following the Panic of 1873, known as the Long Depression, were followed by periods of stagnation intermixed with surges of growth until steadier growth resumed around 1896. The period was characterized by business bankruptcies, low interest rates and deflation. According to David Ames Wells (1891) the economic problems were the result of rapid changes in technology, such as railroads, steam-powered ocean ships, steel displacing iron and the telegraph system.[6] Because there was so much economic growth overall, how much of this period was stagnation remains controversial. See: Long Depression

- The Great Depression of the 1930s and the rest of the period lasting until World War II. Post War Economic Problems, Harris (1943) was written with the expectation that the stagnation would continue after the war ended. See: Causes of the Great Depression.

19th century

[edit]The U.S. economy of the early 19th century was primarily agricultural and suffered from labor shortages.[7] Capital was so scarce before the Civil War that private investors supplied only a fraction of the money to build railroads, despite the large economic advantage railroads offered. As new territories were opened and federal land sales conducted, land had to be cleared and new homesteads established. Hundreds of thousands of immigrants came to the United States every year and found jobs digging canals and building railroads. Because there was little mechanization, almost all work was done by hand or with horses, mules and oxen until the last two decades of the 19th century.[8]

The decade of the 1880s saw great growth in railroads and the steel and machinery industries. Purchase of structures and equipment increased 500% from the previous decade. Labor productivity rose 26.5% and GDP nearly doubled.[9] The workweek during most of the 19th century was over 60 hours, being higher in the first half of the century, with twelve-hour work days common. There were numerous strikes and other labor movements for a ten-hour day. The tight labor market was a factor in productivity gains allowing workers to maintain or increase their nominal wages during the secular deflation that caused real wages to rise in the late 19th century. Labor did suffer temporary setbacks, such as when railroads cut wages during the Long Depression of the mid-1870s; however, this resulted in strikes throughout the nation.

End of stagnation in the U.S. after the Great Depression

[edit]Construction of structures, residential, commercial and industrial, fell off dramatically during the depression, but housing was well on its way to recovering by the late 1930s.[10] The depression years were the period of the highest total factor productivity growth in the United States, primarily to the building of roads and bridges, abandonment of unneeded railroad track and reduction in railroad employment, expansion of electric utilities and improvements wholesale and retail distribution.[10] This helped the United States, which escaped the devastation of World War II, to quickly convert back to peacetime production.

The war created pent up demand for many items, as factories had stopped producing automobiles and other civilian goods to convert to production of tanks, guns, military vehicles and supplies. Tires had been rationed due to shortages of natural rubber; however, the U.S. government built synthetic rubber plants. The U.S. government also built ammonia plants, aluminum smelters, aviation fuel refineries and aircraft engine factories during the war.[10] After the war, commercial aviation, plastics and synthetic rubber would become major industries and synthetic ammonia was used for fertilizer. The end of armaments production freed up hundreds of thousands of machine tools, which were made available for other industries. They were needed in the rapidly growing aircraft manufacturing industry.[11]

The memory of war created a need for preparedness in the United States. This resulted in constant spending for defense programs, creating what President Eisenhower called the military-industrial complex. U.S. birth rates began to recover by the time of World War II, and turned into the baby boom of the postwar decades. A building boom commenced in the years following the war. Suburbs began a rapid expansion and automobile ownership increased.[10] High-yielding crops and chemical fertilizers dramatically increased crop yields and greatly lowered the cost of food, giving consumers more discretionary income. Railroad locomotives switched from steam to diesel power, with a large increase in fuel efficiency. Most importantly, cheap food essentially eliminated malnutrition in countries like the United States and much of Europe. Many trends that began before the war continued:

- The use of electricity grew steadily as prices continued to fall, although at a slower rate than in the early decades. More people purchased washing machines, dryers, refrigerators and other appliances. Air conditioning became increasingly prevalent in households and businesses. See: Diffusion of innovations#Diffusion data

- Infrastructures: The highway system continued to expand.[10] Construction of the interstate highway system started in the late 1950s. The pipeline network continued to expand.[12] Railroad track mileage continued its decline.

- Better roads and increased investment in the distribution system of trucks, warehouses and material-handling equipment, such as forklift trucks, continued to reduce the cost of goods.

- Mechanization of agriculture increased dramatically, especially the use of combine harvesters. Tractor sales peaked in the mid-1950s.[13]

The workweek never returned to the 48 hours or more that was typical before the Great Depression.[14][15]

Stagflation

[edit]The period following the 1973 oil crisis was characterized by stagflation, the combination of low economic and productivity growth and high inflation. The period was also characterized by high interest rates, which is not entirely consistent with secular stagnation. Stronger economic growth resumed and inflation declined during the 1980s. Although productivity never returned to peak levels, it did enjoy a revival with the growth of the computer and communications industries in the 1980s and 1990s.[16] This enabled a recovery in GDP growth rates; however, debt in the period following 1982 grew at a much faster rate than GDP.[17][18] The U.S. economy experienced structural changes following the stagflation. Steel consumption peaked in 1973, both on an absolute and per-capita basis, and never returned to previous levels.[19] The energy intensity of the United States and many other developed economies also began to decline after 1973. Health care expenditures rose to over 17% of the economy.

Productivity slowdown

[edit]Productivity growth began to slow down sharply in developed countries after 1973, but there was a revival in the 1990s which still left productivity growth below the peak decades earlier in the 20th century.[16][20][21] Productivity growth in the U.S. slowed again since the mid-2000s.[22] A recent book titled The Great Stagnation: How America Ate All the Low-Hanging Fruit of Modern History, Got Sick and Will (Eventually) Feel better by Tyler Cowen is one of the latest of several stagnation books written in recent decades. Turning Point by Robert Ayres and The Evolution of Progress by C. Owen Paepke were earlier books that predicted the stagnation.

Stagnation and the financial explosion: the 1980s

[edit]A prescient analysis of stagnation and what is now called financialization was provided in the 1980s by Harry Magdoff and Paul Sweezy, coeditors of the independent socialist journal Monthly Review. Magdoff was a former economic advisor to Vice President Henry A. Wallace in Roosevelt’s New Deal administration, while Sweezy was a former Harvard economics professor. In their 1987 book, Stagnation and the Financial Explosion, they argued, based on Keynes, Hansen, Michał Kalecki, and Marx, and marshaling extensive empirical data, that, contrary to the usual way of thinking, stagnation or slow growth was the norm for mature, monopolistic (or oligopolistic) economies, while rapid growth was the exception.[23]

Private accumulation had a strong tendency to weak growth and high levels of excess capacity and unemployment/underemployment, which could, however, be countered in part by such exogenous factors as state spending (military and civilian), epoch-making technological innovations (for example, the automobile in its expansionary period), and the growth of finance. In the 1980s and 1990s Magdoff and Sweezy argued that a financial explosion of long duration was lifting the economy, but this would eventually compound the contradictions of the system, producing ever bigger speculative bubbles, and leading eventually to a resumption of overt stagnation.

Post-2008 period

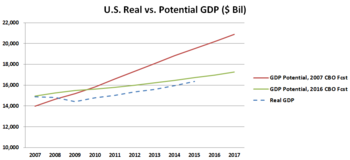

[edit]

Secular stagnation was dusted off by Hans-Werner Sinn in a 2009 article [25] dismissing the threat of inflation, and became popular again when Larry Summers invoked the term and concept during a 2013 speech at the IMF.[26]The Economist criticizes secular stagnation as "a baggy concept, arguably too capacious for its own good".[1] Warnings similar to secular stagnation theory have been issued after all deep recessions, but they all turned out to be wrong because they underestimated the potential of existing technologies.[3]

Paul Krugman, writing in 2014, clarified that it refers to "the claim that underlying changes in the economy, such as slowing growth in the working-age population, have made episodes like the past five years in Europe and the United States, and the last 20 years in Japan, likely to happen often. That is, we will often find ourselves facing persistent shortfalls of demand, which can’t be overcome even with near-zero interest rates."[27] At its root is "the problem of building consumer demand at a time when people are less motivated to spend".[28]

One theory is that the boost in growth by the internet and technological advancement in computers of the new economy does not measure up to the boost caused by the great inventions of the past. An example of such a great invention is the assembly line production method of Fordism. The general form of the argument has been the subject of papers by Robert J. Gordon.[29] It has also been written about by Owen. C. Paepke and Tyler Cowen.[30]

Secular stagnation been linked to the rise of the digital economy. Carl Benedikt Frey, for example, has suggested that digital technologies are much less capital-absorbing, creating only little new investment demand relative to other revolutionary technologies.[31] Another is that the damage done by the Great Recession was so long-lasting and permanent, so many workers will never get jobs again, that we really cannot recover.[28] A third is that there is a "persistent and disturbing reluctance of businesses to invest and consumers to spend", perhaps in part because so much of the recent gains have gone to the people at the top, and they tend to save more of their money than people—ordinary working people who can't afford to do that.[28] A fourth is that advanced economies are just simply paying the price for years of inadequate investment in infrastructure and education, the basic ingredients of growth.[28]

Episodes

[edit]Japan: 1991–present

[edit]Japan has been suffering economic or secular stagnation for most of the period since the early 1990s.[32][33] Economists, such as Paul Krugman, attribute the stagnation to a liquidity trap (a situation in which monetary policy is unable to lower nominal interest rates because these are close to zero) exacerbated by demographics factors.[34]

World since 2008

[edit]Economists have asked whether the low economic growth rate in the developed world leading up to and following the subprime mortgage crisis of 2007–2008 was due to secular stagnation. Paul Krugman wrote in September 2013: "[T]here is a case for believing that the problem of maintaining adequate aggregate demand is going to be very persistent – that we may face something like the 'secular stagnation' many economists feared after World War II." Krugman wrote that fiscal policy stimulus and higher inflation (to achieve a negative real rate of interest necessary to achieve full employment) may be potential solutions.[35]

Larry Summers presented his view during November 2013 that secular (long-term) stagnation may be a reason that U.S. growth is insufficient to reach full employment: "Suppose then that the short term real interest rate that was consistent with full employment [i.e., the "natural rate"] had fallen to negative two or negative three percent. Even with artificial stimulus to demand you wouldn't see any excess demand. Even with a resumption in normal credit conditions you would have a lot of difficulty getting back to full employment."[36][37]

Robert J. Gordon wrote in August 2012: "Even if innovation were to continue into the future at the rate of the two decades before 2007, the U.S. faces six headwinds that are in the process of dragging long-term growth to half or less of the 1.9 percent annual rate experienced between 1860 and 2007. These include demography, education, inequality, globalization, energy/environment, and the overhang of consumer and government debt. A provocative 'exercise in subtraction' suggests that future growth in consumption per capita for the bottom 99 percent of the income distribution could fall below 0.5 percent per year for an extended period of decades".[38]

The German Institute for Economic Research sees a connection between secular stagnation and the regime of low interest rates (zero interest-rate policy, negative interest rates).[39]

See also

[edit]- Brezhnev stagnation

- 1991 Indian economic crisis

- Hindu rate of growth

- Lost Decade (Japan)

- The End of Work

- Business cycle

- Degrowth

- Recession

References

[edit]- ^ a b W., P. (16 August 2014). "Secular stagnation: Fad or fact?". The Economist.

- ^ "U.S. Secular Stagnation?". 23 December 2015.

- ^ a b Pagano and Sbracia (2014) "The secular stagnation hypothesis: a review of the debate and some insights." Bank of Italy Questioni di Economia e Finanza occasional paper series number QEF-231.

- ^ "Definition of secular stagnation". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 16 March 2019. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ a b Sweezy, Alan (1943). "Chapter IV Secular Stagnation". In Harris, Seymour E. (ed.). Postwar Economic Problems. New York, London: McGraw Hill Book Co. pp. 67–82.

- ^ Wells, David A. (1891). Recent Economic Changes and Their Effect on Production and Distribution of Wealth and Well-Being of Society. New York: D. Appleton and Co. ISBN 978-0-543-72474-8.

- ^ Habakkuk, H. J. (1962). American and British Technology in the Nineteenth Century. London; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521094474.

- ^ Hunter, Louis C.; Bryant, Lynwood (1991). A History of Industrial Power in the United States, 1730–1930. Vol. 3: The Transmission of Power. Cambridge, Mass.; London: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-08198-6.

- ^ Rothbard, Murray (2002). History of Money and Banking in the United States (PDF). Ludwig Von Mises Inst. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-945466-33-8.

- ^ a b c d e Field, Alexander J. (2011). A Great Leap Forward: 1930s Depression and U.S. Economic Growth. New Haven; London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15109-1.

- ^ Hounshell, David A. (1984), From the American System to Mass Production, 1800–1932: The Development of Manufacturing Technology in the United States, Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-2975-8, LCCN 83016269, OCLC 1104810110

- ^ "BTS | Table 1-1: System Mileage within the United States (Statute miles)". Archived from the original on 18 April 2008. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ White, William J. "Economic History of Tractors in the United States". Archived from the original on 24 October 2013.

- ^ "Hours of Work in U.S. History". 2010. Archived from the original on 26 October 2011.

- ^ Whaples, Robert (June 1991). "The Shortening of the American Work Week: An Economic and Historical Analysis of Its Context, Causes, and Consequences, The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 51, No. 2; pp. 454–457".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Field, Alexander (2004). "Technological Change and Economic Growth the Interwar Years and the 1990s" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 March 2012.

- ^ [1] There are numerous graphs of total debt/GDP available on the Internet.

- ^ Roche, Cullen (2010). "Total Debt to GDP Trumps Everything Else".

- ^ Smil, Vaclav (2006). Transforming the Twentieth Century: Technical Innovations and Their Consequences. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 112. In the U.S., steel consumption peaked at just under 700 kg per capita and declined to just over 400 kg by 2000.

- ^ Kendrick, John (1 October 1991). "U.S. Productivity Performance in Perspective, Business Economics".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Field, Alezander J. (2007). "U.S. Economic Growth in the Gilded Age, Journal of Macroeconomics 31": 173–190.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ The Recent Rise and Fall of Rapid Productivity Growth

- ^ Magdoff, Harry; Sweezy, Paul (1987). Stagnation and the Financial Explosion. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- ^ Larry Summers – U.S. Economic Prospects – Keynote Address at the NABE Conference 2014

- ^ Hans-Werner Sin, Forget Inflation, February 26, 2009

- ^ "IMF Fourteenth Annual Research Conference in Honor of Stanley Fischer". 8 November 2013.

- ^ Krugman, Paul (15 August 2014). "Secular Stagnation: The Book". New York Times.

- ^ a b c d Inskeep, Steve (9 September 2014). "Is The Economy Suffering From Secular Stagnation?". NPR.

- ^ Gordon, Robert J. (2000). "Does the New Economy Measure Up to the Great Inventions of the Past?" (PDF). Journal of Economic Perspectives. 14 (4): 49–74. doi:10.1257/jep.14.4.49.

- ^ Paepke, C. Owen (1993). The Evolution of Progress: The End of Economic Growth and the Beginning of Human Transformation. New York; Toronto: Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-41582-4.

- ^ Frey, Carl Benedikt (2015). "The End of Economic Growth? How the Digital Economy Could Lead to Secular Stagnation". Scientific American. 312 (1).

- ^ Lessons from Japan's Secular Stagnation The Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry

- ^ Hoshi, Takeo; Kashyap, Anil K. (2004). "Japan's Financial Crisis and Economic Stagnation". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 18 (1 (Winter)): 3–26. doi:10.1257/089533004773563412.

- ^ Krugman, Paul (2009). The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008. W.W. Norton Company Limited. ISBN 978-0-393-07101-6.

- ^ Paul Krugman – Bubbles, Regulation and Secular Stagnation – September 25, 2013

- ^ "Marco Nappollini – Pieria.com – Secular Stagnation and Post Scarcity – November 19, 2013". Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ Paul Krugman – Conscience of a Liberal Blog – Secular Stagnation, Coalmines, Bubbles, and Larry Summers – November 16, 2013

- ^ Robert J. Gordon – Is U.S. Economic Growth Over? Faltering Innovation Confronts the Six Headwinds – August 2012 Archived September 18, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ German Institute for Economic Research, January 30, 2017: "The Natural Rate of Interest and Secular Stagnation"

Further reading

[edit]- Ayres, Robert U. (1998). Turning Point: An End to the Growth Paradigm. London: Earthscan Publications. ISBN 978-1-85383-439-4.

- Rifkin, Jeremy (1995). The End of Work: The Decline of the Global Labor Force and the Dawn of the Post-Market Era. Putnam Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-87477-779-6.

- Ayres, Robert (1989). "Technological Transformations and Long Waves" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Constable, George; Somerville, Bob (2003). A Century of Innovation: Twenty Engineering Achievements That Transformed Our Lives. Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press. ISBN 978-0-309-08908-1.

- Paepke, C. Owen (1993). The Evolution of Progress: The End of Economic Growth and the Beginning of Human Transformation. New York, Toronto: Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-41582-4.

- Bloomberg-Secular Stagnation Archived 25 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine