Sigurd

Sigurd (Old Norse: Sigurðr [ˈsiɣˌurðr]) or Siegfried (Middle High German: Sîvrit) is a legendary hero of Germanic heroic legend, who killed a dragon—known in some Old Norse sources as Fáfnir—and who was later murdered, in the Nordic countries with the epithet "Fáfnir's bane" (Danish: Fafnersbane, Icelandic: Fáfnisbani, Norwegian: Fåvnesbane, Swedish: Fafnesbane), but widely also "the Dragon Slayer". In both the Norse and continental Germanic tradition, Sigurd is portrayed as dying as the result of a quarrel between his wife (Gudrun/Kriemhild) and another woman, Brunhild, whom he has tricked into marrying the Burgundian king Gunnar/Gunther. His slaying of a dragon and possession of the hoard of the Nibelungen is also common to both traditions. In other respects, however, the two traditions appear to diverge. The most important works to feature Sigurd are the Nibelungenlied, the Völsunga saga, and the Poetic Edda. He also appears in numerous other works from both Germany and Scandinavia, including a series of medieval and early modern Scandinavian ballads.

Sigurd's story is first attested on a series of carvings, including runestones from Sweden and stone crosses from the British Isles, dating from the 11th century. It is possible that he was inspired by one or more figures from the Frankish Merovingian dynasty, with Sigebert I being the most popular contender. Older scholarship sometimes connected him with Arminius, victor of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest.[1] He may also have a purely mythological origin.

Richard Wagner used the legends about Sigurd/Siegfried in his operas Siegfried and Götterdämmerung. Wagner relied heavily on the Norse tradition in creating his version of Siegfried. His depiction of the hero has influenced many subsequent depictions. In the 19th and 20th centuries, Siegfried became heavily associated with German nationalism.

The Thidrekssaga finishes its tale of Sigurd by saying:

[E]veryone said that no man now living or ever after would be born who would be equal to him in strength, courage, and in all sorts of courtesy, as well as in boldness and generosity that he had above all men, and that his name would never perish in the German tongue, and the same was true with the Norsemen.[2]

Etymology

[edit]The names Sigurd and Siegfried do not share the same etymology. Both have the same first element, Proto-Germanic *sigi-, meaning victory. The second elements of the two names are different, however: in Siegfried, it is Proto-Germanic *-frið, meaning peace; in Sigurd, it is Proto-Germanic *-ward, meaning protection.[3] Although they do not share the same second element, it is clear that surviving Scandinavian written sources held Siegfried to be the continental version of the name they called Sigurd.[4]

The normal form of Siegfried in Middle High German is Sîvrit or Sîfrit, with the *sigi- element contracted. This form of the name had been common even outside of heroic poetry since the 9th century, though the form Sigevrit is also attested, along with the Middle Dutch Zegevrijt. In Early Modern German, the name develops to Seyfrid or Seufrid (spelled Sewfrid).[3] The modern form Siegfried is not attested frequently until the 17th century, after which it becomes more common.[5] In modern scholarship, the form Sigfrid is sometimes used.[6]

The Old Norse name Sigurðr is contracted from an original *Sigvǫrðr,[3] which in turn derives from an older *Sigi-warðuR.[7] The Danish form Sivard also derives from this form originally.[8] Hermann Reichert notes that the form of the root -vǫrðr instead of -varðr is only found in the name Sigurd, with other personal names instead using the form -varðr; he suggests that the form -vǫrðr may have had religious significance, whereas -varðr was purely non-religious in meaning.[9]

There are competing theories as to which name is original. Names equivalent to Siegfried are first attested in Anglo-Saxon Kent in the 7th century and become frequent in Anglo-Saxon England in the 9th century.[3] Jan-Dirk Müller argues that this late date of attestation means that it is possible that Sigurd more accurately represents the original name.[10] Wolfgang Haubrichs suggests that the form Siegfried arose in the bilingual Frankish kingdom as a result of romance-language influence on an original name *Sigi-ward. According to the normal phonetic principles, the Germanic name would have become Romance-language *Sigevert, a form which could also represent a Romance-language form of Germanic Sigefred.[11] He further notes that *Sigevert would be a plausible Romance-language form of the name Sigebert (see Origins) from which both names could have arisen.[12] As a second possibility, Haubrichs considers the option that metathesis of the r in *Sigi-ward could have taken place in Anglo-Saxon England, where variation between -frith and -ferth is well documented.[12]

Reichert, on the other hand, notes that Scandinavian figures who are attested in pre-12th-century German, English, and Irish sources as having names equivalent to Siegfried are systematically changed to forms equivalent to Sigurd in later Scandinavian sources. Forms equivalent to Sigurd, on the other hand, do not appear in pre-11th-century non-Scandinavian sources, and older Scandinavian sources sometimes call persons Sigfroðr Sigfreðr or Sigfrǫðr who are later called Sigurðr.[13] He argues from this evidence that a form equivalent to Siegfried is the older form of Sigurd's name in Scandinavia as well.[14]

Origins

[edit]Unlike many figures of Germanic heroic tradition, Sigurd cannot be easily identified with a historical figure. The most popular theory is that Sigurd has his origins in one or several figures of the Merovingian dynasty of the Franks: the Merovingians had several kings whose name began with the element *sigi-. In particular, the murder of Sigebert I (d. 575), who was married to Brunhilda of Austrasia, is often cited as a likely inspiration for the figure,[1][15] a theory that was first proposed in 1613.[16] Sigibert was murdered by his brother Chilperic I at the instigation of Chilperic's wife queen Fredegunda. If this theory is correct, then in the legend, Fredegunda and Brunhilda appear to have switched roles,[17] while Chilperic has been replaced with Gunther.[18]

Jens Haustein (2005) argues that, while the story of Sigurd appears to have Merovingian resonances, no connection to any concrete historical figure or event is convincing.[19] As the Merovingian parallels are not exact, other scholars also fail to accept the proposed model.[10][20] But the Sigurd/Siegfried figure, rather than being based on the Merovingian alone, may be a composite of additional historical personages, e.g., the "Caroliginian Sigifridus" alias Godfrid, Duke of Frisia (d. 855) according to Edward Fichtner (2015).[21]

Franz-Joseph Mone (1830) had also believed Siegfried to be an amalgamation of several historical figures, and was the first to suggest possible connection with the Germanic hero Arminius from the Roman period, famed for defeating Publius Quinctilius Varus's three legions at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD.[22] Later Adolf Giesebrecht (1837) asserted outright that Sigurd/Siegfried was a mythologized version of Arminius.[22] Although this position was taken more recently by Otto Höfler (beginning in 1959),[a] who also suggested that Gnita-Heath, the name of the place where Sigurd kills the dragon in the Scandinavian tradition, represents the battlefield for the Teutoburg Forest,[23] modern scholarship generally dismisses a connection between Sigurd and Arminius as tenuous speculation.[1][10][19] The idea that Sigurd derives from Arminius nevertheless continues to be promoted outside of the academic sphere, including in popular magazines such as Der Spiegel.[24]

It has also been suggested by others that Sigurd may be a purely mythological figure without a historical origin.[25][26] Nineteenth-century scholars frequently derived the Sigurd story from myths about Germanic deities including Odin, Baldr, and Freyr; such derivations are no longer generally accepted.[19] Catalin Taranu argues that Sigurd's slaying of the dragon ultimately has Indo-European origins, and that this story later became attached to the story of the murder of the Merovingian Sigebert I.[27]

Continental Germanic traditions and attestations

[edit]

Continental Germanic traditions about Siegfried enter writing with the Nibelungenlied around 1200. The German tradition strongly associates Siegfried with a kingdom called "Niederland" (Middle High German Niderlant), which, despite its name, is not the same as the modern Netherlands, but describes Siegfried's kingdom around the city of Xanten.[28] The late medieval Heldenbuch-Prosa identifies "Niederland" with the area around Worms but describes it as a separate kingdom from King Gibich's land (i.e. the Burgundian kingdom).[29]

Nibelungenlied

[edit]

The Nibelungenlied gives two contradictory descriptions of Siegfried's youth. On the level of the main story, Siegfried is given a courtly upbringing in Xanten by his father king Siegmund and mother Sieglind. When he is seen coming to Worms, capital of the Burgundian kingdom to woo the princess Kriemhild, however, the Burgundian vassal Hagen von Tronje narrates a different story of Siegfried's youth: according to Hagen, Siegfried was a wandering warrior (Middle High German recke) who won the hoard of the Nibelungen as well as the sword Balmung and a cloak of invisibility (Tarnkappe) that increases the wearer's strength twelve times. He also tells an unrelated tale about how Siegfried killed a dragon, bathed in its blood, and thereby received skin as hard as horn that makes him invulnerable. Of the features of young Siegfried's adventures, only those that are directly relevant to the rest of the story are mentioned.[30]

In order to win the hand of Kriemhild, Siegfried becomes a friend of the Burgundian kings Gunther, Gernot, and Giselher. When Gunther decides to woo the warlike queen of Iceland, Brünhild, he offers to let Siegfried marry Kriemhild in exchange for Siegfried's help in his wooing of Brünhild. As part of Siegfried's help, they lie to Brünhild and claim that Siegfried is Gunther's vassal. Any wooer of Brünhild's must accomplish various physical tasks, and she will kill any man who fails. Siegfried, using his cloak of invisibility, aids Gunther in each task. Upon their return to Worms, Siegfried marries Kriemhild following Gunther's marriage to Brünhild. On Gunther's wedding night, however, Brünhild prevents him from sleeping with her, tying him up with her belt and hanging him from a hook. The next night, Siegfried uses his cloak of invisibility to overpower Brünhild, allowing Gunther to sleep with her. Although he does not sleep with Brünhild, Siegfried takes her belt and ring, later giving them to Kriemhild.[31][32]

Siegfried and Kriemhild have a son, whom they name Gunther. Later, Brünhild and Kriemhild begin to fight over which of them should have precedence, with Brünhild believing that Kriemhild is only the wife of a vassal. Finally, in front of the door of the cathedral in Worms, the two queens argue who should enter first. Brünhild openly accuses Kriemhild of being married to a vassal, and Kriemhild claims that Siegfried took Brünhild's virginity, producing the belt and ring as proof. Although Siegfried denies this publicly, Hagen and Brünhild decide to murder Siegfried, and Gunther acquiesces. Hagen tricks Kriemhild into telling him where Siegfried's skin is vulnerable, and Gunther invites Siegfried to take part in a hunt in the Waskenwald (the Vosges).[33] When Siegfried is slaking his thirst at a spring, Hagen stabs him on the vulnerable part of his back with a spear. Siegfried is mortally wounded but still attacks Hagen, before cursing the Burgundians and dying. Hagen arranges to have Siegfried's corpse thrown outside the door to Kriemhild's bedroom. Kriemhild mourns Siegfried greatly and he is buried in Worms.[34]

The redaction of the text known as the Nibelungenlied C makes several small changes to localizations in the text: Siegfried is not killed in the Vosges, but in the Odenwald, with the narrator claiming that one can still visit the spring where he was killed near the village of Odenheim (today part of Östringen).[35] The redactor states the Siegfried was buried at the abbey of Lorsch rather than Worms. It is also mentioned that he was buried in a marble sarcophagus—this may be connected to actual marble sarcophagi that were displayed in the abbey, having been dug up following a fire in 1090.[36]

Rosengarten zu Worms

[edit]

In the Rosengarten zu Worms (c. 1250), Siegfried is betrothed to Kriemhild and is one of the twelve heroes who defends her rose garden in Worms. Kriemhild decides that she would like to test Siegfried's mettle against the hero Dietrich von Bern, and so she invites him and twelve of his warriors to fight her twelve champions. When the fight is finally meant to begin, Dietrich initially refuses to fight Siegfried on the grounds that the dragon's blood has made Siegfried's skin invulnerable. Dietrich is convinced to fight Siegfried by the false news that his mentor Hildebrand is dead and becomes so enraged that he begins to breathe fire, melting Siegfried's protective layer of horn on his skin. He is thus able to penetrate Siegfried's skin with his sword, and Siegfried becomes so afraid that he flees to Kriemhild's lap. Only the reappearance of Hildebrand prevents Dietrich from killing Siegfried.[37][38]

Siegfried's role as Kriemhild's fiancé does not accord with the Nibelungenlied, where the two are never formally betrothed.[39] The detail that Kriemhild's father is named Gibich rather than Dancrat, the latter being his name in the Nibelungenlied, shows that the Rosengarten does include some old traditions absent in that poem, although it is still highly dependent on the Nibelungenlied. Some of the details agree with the Thidrekssaga.[40][41] Rosengarten A mentions that Siegfried was raised by a smith named Eckerich.[42]

Þiðrekssaga

[edit]Although the Þiðrekssaga (c. 1250) is written in Old Norse, the majority of the material is translated from German (particularly Low German) oral tales, as well as possibly some from German written sources such as the Nibelungenlied.[43] Therefore, it is included here.

The Thidrekssaga refers to Siegfried both as Sigurd (Sigurðr) and an Old Norse approximation of the name Siegfried, Sigfrœð.[44] He is the son of king Sigmund of Tarlungaland (probably a corruption of Karlungaland, i.e. the land of the Carolingians)[45] and queen Sisibe of Spain. When Sigmund returns from a campaign one day, he discovers his wife is pregnant, and believing her to be unfaithful to him, he exiles her to the "Swabian Forest" (the Black Forest?),[46] where she gives birth to Sigurd. She dies after some time, and Sigurd is suckled by a hind before being found by the smith Mimir. Mimir tries to raise the boy, but Sigurd is so unruly that Mimir sends him to his brother Regin, who has transformed into a dragon, in the hopes that he will kill the boy. Sigurd, however, slays the dragon and tastes its flesh, whereby he learns the language of the birds and of Mimir's treachery. He smears himself with dragon's blood, making his skin invulnerable, and returns to Mimir. Mimir gives him weapons to placate him, but Sigurd kills him anyway. He then encounters Brynhild (Brünhild), who gives him the horse Grane, and goes to King Isung of Bertangenland.[47]

One day Thidrek (Dietrich von Bern) comes to Bertangenland; he fights against Sigurd for three days. Thidrek is unable to wound Sigurd because of his invulnerable skin, but on the third day, Thidrek receives the sword Mimung, which can cut through Sigurd's skin, and defeats him. Thidrek and Sigurd then ride to King Gunnar (Gunther), where Sigurd marries Gunnar's sister Grimhild (Kriemhild). Sigurd recommends to Gunnar that he marry Brynhild, and the two ride to woo for her. Brynhild now claims that Sigurd had earlier said he would marry her (unmentioned before in the text), but eventually she agrees to marry Gunnar. She will not, however, allow Gunnar to consummate the marriage, and so with Gunnar's agreement, Sigurd takes Gunnar's shape and deflowers Brynhild, taking away her strength.[48] The heroes then return with Brynhild to Gunnar's court.[49]

Sometime later, Grimhild and Brynhild fight over who has a higher rank. Brynhild claims that Sigurd is not of noble birth, after which Grimhild announces that Sigurd and not Gunnar deflowered Brynhild. Brynhild convinces Gunnar and Högni (Hagen) to murder Sigurd, which Högni does while Sigurd is drinking from a spring on a hunt. The brothers then place his corpse in Grimhild's bed, and she mourns.[50]

The author of the saga has made a number of changes to create a more or less coherent story out of the many oral and possibly written sources that he used to create the saga.[51] The author mentions alternative Scandinavian versions of many of these same tales, and appears to have changed some details to match the stories known by his Scandinavian audience.[52][53] This is true in particular for the story of Sigurd's youth, which combines elements from the Norse and continental traditions attested later in Das Lied vom Hürnen Seyfrid, but also contains an otherwise unattested story of Siegfried's parents.[54]

The Thidrekssaga makes no mention of how Sigurd won the hoard of the Nibelungen.[55]

Biterolf und Dietleib

[edit]The second half of the heroic poem Biterolf und Dietleib (between 1250 and 1300)[56] features a war between the Burgundian heroes of the Nibelungenlied and the heroes of the cycle around Dietrich von Bern, something likely inspired by the Rosengarten zu Worms. In this context, it also features a fight between Siegfried and Dietrich in which Dietrich defeats Siegfried after initially appearing cowardly. The text also features a fight between Siegfried and the hero Heime, in which Siegfried knocks Heime's famous sword Nagelring out of his hand, after which both armies fight for control over the sword.[57]

The text also relates that Dietrich once brought Siegfried to Etzel's court as a hostage, something which is also alluded to in the Nibelungenlied.[58]

Heldenbuch-Prosa

[edit]The so-called "Heldenbuch-Prosa", first found in the 1480 Heldenbuch of Diebolt von Hanowe and afterwards contained in printings until 1590, is considered one of the most important attestations of a continued oral tradition outside of the Nibelungenlied, with many details agreeing with the Thidrekssaga.[59]

The Heldenbuch-Prosa has very little to say about Siegfried: it notes that he was the son of King Siegmund, came from "Niederland", and was married to Kriemhild. Unattested in any other source, however, is that Kriemhild orchestrated the disaster at Etzel's court in order to avenge Siegfried being killed by Dietrich von Bern. According to the Heldenbuch-Prosa, Dietrich killed Siegfried fighting in the rose garden at Worms (see the Rosengarten zu Worms section above). This may have been another version of Siegfried's death that was in oral circulation.[60]

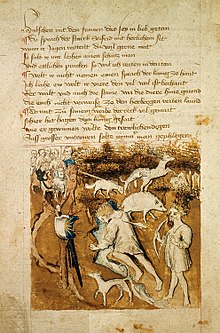

Das Lied vom Hürnen Seyfrid

[edit]

Das Lied vom Hürnen Seyfrid (the song of horn-skinned Siegfried) is a late medieval/early modern heroic ballad that gives an account of Siegfried's adventures in his youth. It agrees in many details with the Thidrekssaga and other Old Norse accounts over the Nibelungenlied, suggesting that these details existed in an oral tradition about Siegfried in Germany.[61]

According to the Hürnen Seyfrid, Siegfried had to leave his father Siegmund's court for his uncouth behavior and was raised by a smith in the forest. He was so unruly, however, that the smith arranged for him to be killed by a dragon. Siegfried was able to kill the dragon, however, and eventually kills many more by trapping them under logs and setting them on fire. The dragon's skin, described as hard as horn, melts, and Siegfried sticks his finger into it, discovering that his finger is now hard as horn as well. He smears himself with the melted dragon skin everywhere except for one spot. Later, he stumbles upon the trail of another dragon that has kidnapped princess Kriemhild of Worms. With the help of the dwarf Eugel, Siegfried fights the giant Kuperan, who has the key to the mountain Kriemhild has been taken to. He rescues the princess and slays the dragon, finding the treasure of the Nibelungen inside the mountain. Eugel prophesies, however, the Siegfried only has eight years to live. Realizing he will not be able to use the treasure, Siegfried dumps the treasure into the Rhine on his way to Worms. He marries Kriemhild and rules there together with her brothers Gunther, Hagen, and Giselher, but they resent him and have him killed after eight years.[62]

Other traditions and attestations

[edit]

The Icelandic Abbot Nicholaus of Thvera records that while travelling through Westphalia, he was shown the place where Sigurd slew the dragon (called Gnita-Heath in the Norse tradition) between two villages south of Paderborn.[63]

In a song of the mid-13th-century wandering lyric poet Der Marner, "the death of Siegfried" (Sigfrides [...] tôt) is mentioned as a popular story that the German courtly public enjoys hearing, along with "the hoard of the Nibelungs" (der Nibelunge hort).[64]

The chronicles of the city of Worms record that when Emperor Frederick III visited the city in 1488, he learned that the townspeople said that the "giant Siegfried" (gigas [...] Sifridus des Hörnen) was buried in the cemetery of St. Meinhard and St. Cecilia. Frederick ordered the graveyard dug up—according to one Latin source, he found nothing, but a German chronicle reports that he found a skull and some bones that were larger than normal.[65][66]

Scandinavian traditions and attestations

[edit]In contrast to the surviving continental traditions, Scandinavian stories about Sigurd have a strong connection to Germanic mythology. While older scholarship took this to represent the original form of the Sigurd story, newer scholarship is more inclined to see it as a development of the tradition that is unique to Scandinavia.[67] While some elements of the Scandinavian tradition may indeed be older than the surviving continental witnesses, a good deal seems to have been transformed by the context of the Christianization of Iceland and Scandinavia: the frequent appearance of the heathen gods gives the heroic stories the character of an epoch that is irrevocably over.[68]

Although the earliest attestations for the Scandinavian tradition are pictorial depictions, because these images can only be understood with a knowledge of the stories they depict, they are listed last here.

The Prose Edda

[edit]

The so-called Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson is the earliest non-pictorial attestation of the Scandinavian version of Sigurd's life, dating to around 1220.[69] Snorri retells the story of Sigurd in several chapters of the section of the poem called Skáldskaparmál.[70] His presentation of the story is very similar to that found in the Völsunga saga (see below), but is considerably shorter.[71] This version does not mention Sigurd's vengeance for the death of his father.[72] The text identifies Sigurd as being raised in a place called "Thjod."[73]

Sigurd is raised at the court of king Hjálprek, receives the sword Gram from the smith Regin, and slays the dragon Fafnir on Gnita-Heath by lying in a pit and stabbing it in the heart from underneath. Sigurd tastes the dragon's blood and understands the birds when they say that Regin will kill him in order to acquire the dragon's gold. He then kills Regin and takes the hoard of the Nibelungen for himself. He rides away with the hoard and then awakens the valkyrie Brynhild by cutting the armor from her, before coming to king Gjuki's kingdom. There he marries Gjuki's daughter, Gudrun, and helps her brother, Gunnar, to acquire Brynhild's hand from her brother Atli. Sigurd deceives Brynhild by taking Gunnar's shape when Gunnar cannot fulfill the condition that he ride through a wall of flames to wed her; Sigurd rides through the flames and weds Brynhild, but does not sleep with her, placing his sword between them in the marriage bed. Sigurd and Gunnar then return to their own shapes.

Sigurd and Gudrun have two children, Svanhild and young Sigmund. Later, Brynhild and Gudrun quarrel and Gudrun reveals that Sigurd was the one who rode through the fire, and shows a ring that Sigurd took from Brynhild as proof. Brynhild then arranges to have Sigurd killed by Gunnar's brother Guthorm. Guthorm stabs Sigurd in his sleep, but Sigurd is able to slice Guthorm in half by throwing his sword before dying. Guthorm has also killed Sigurd's three-year-old son Sigmund. Brynhild then kills herself and is burned on the same pyre as Sigurd.[74]

The Poetic Edda

[edit]The Poetic Edda appears to have been compiled around 1270 in Iceland, and assembles mythological and heroic songs of various ages.[75] The story of Sigurd forms the core of the heroic poems collected here.[76] However, the details of Sigurd's life and death in the various poems contradict each other, so that "the story of Sigurd does not emerge clearly from the Eddic verse".[77]

Generally, none of the poems are thought to have been composed before 900 and some appear to have been written in the 13th century.[78] It is also possible that apparently old poems have been written in an archaicizing style and that apparently recent poems are reworkings of older material, so that reliable dating is impossible.[76]

The Poetic Edda identifies Sigurd as a king of the Franks.[79]

Frá dauða Sinfjötla

[edit]Frá dauða Sinfjötla is a short prose text between the songs. Sigurd is born at the end of the poem; he is the posthumous son of Sigmund, who dies fighting the sons of Hunding, and Hjordis. Hjordis is married to the son of Hjálprek and allowed to raise Sigurd in Hjálprek's home.[80]

Grípisspá

[edit]In Grípisspá, Sigurd goes to Grípir, his uncle on his mother's side, in order to hear a prophecy about his life. Grípir tells Sigurd that he will kill Hunding's sons, the dragon Fafnir, and the smith Regin, acquiring the hoard of the Nibelungen. Then he will wake a valkyrie and learn runes from her. Grípir does not want to tell Sigurd any more, but Sigurd forces him to continue. He says that Sigurd will go to the home of Heimer and betroth himself to Brynhild, but then at the court of King Gjuki he will receive a potion that will make him forget his promise and marry Gudrun. He will then acquire Brynhild as a wife for Gunnar and sleep with Brynhild without having sex with her. Brynhild will recognize the deception, however, and claim that Sigurd did sleep with her, and this will cause Gunnar to have him killed.[81]

The poem is likely fairly young and seems to have been written to connect the previous poems about Helgi Hundingsbane with those about Sigurd.[82]

Poems of Sigurd's Youth

[edit]The following three poems form a single unit in the manuscript of the Poetic Edda, but are split into three by modern scholars.[82] They likely contain old material, but the poems themselves appear to be relatively recent versions.[83] The poems also mix two conceptions of Sigurd: on the one hand, he is presented as an intelligent royal prince, on the other, he is raised by the smith Regin and is presented as stupid. It is most likely that Sigurd's youth with the smith, his stupidity, and his success through supernatural aid rather than his own cunning is the more original of these conceptions.[84]

Reginsmál

[edit]In Reginsmál, the smith Regin, who is staying at the court of Hjálprek, tells Sigurd of a hoard that the gods had had to assemble in order to compensate the family of Ótr, whom they had killed. Fafnir, Ótr's brother, guards the treasure now and has turned into a dragon. Regin wants Sigurd to kill the dragon. He makes the sword Gram for Sigurd, but Sigurd chooses to kill Lyngvi and the other sons of Hunding before he kills the dragon. On his way he is accompanied by Odin. After killing the brothers in battle and carving a blood eagle on Lyngvi, Regin praises Sigurd's ferocity in battle.[85]

Fáfnismál

[edit]In Fáfnismál, Sigurd accompanies Regin to Gnita-Heath, where he digs a pit. He stabs Fafnir through the heart from underneath when the dragon passes over the pit. Fafnir, before he dies, tells Sigurd some wisdom and warns him of the curse that lays on the hoard. Once the dragon is dead, Regin tears out Fafnir's heart and tells Sigurd to cook it. Sigurd checks whether the heart is done with his finger and burns it. When he puts his finger into his mouth, he can understand the language of the birds, who warn him of Regin's plan to kill him. He kills the smith and is told by the birds to go to a palace surrounded by flames where the valkyrie Sigdrifa is asleep. Sigurd heads there, loading the hoard on his horse.[85]

Sigrdrífumál

[edit]In Sigrdrífumál, Sigurd rides to Hindarfjal, where he finds a wall made of shields. Inside he finds a sleeping woman who is wearing armor that seems to have grown into her skin. Sigurd cuts open the armor and Sigdrifa, the valkyrie, wakes up. She teaches him the runes, some magic spells, and gives him advice.[85]

Brot af Sigurðarkviðu

[edit]

Only the ending of Brot af Sigurðarkviðu is preserved. The poem begins with Högni and Gunnar discussing whether Sigurd needs to be murdered. Högni suggests that Brynhild may be lying that Sigurd slept with Brynhild. Then Guthorm, Gunnar and Högni's younger brother, murders Sigurd in the forest, after which Brynhild admits that Sigurd never slept with her.[86]

The poem shows the influence of continental Germanic traditions, as it portrays Sigurd's death in the forest rather than in his bed.[87]

Frá dauða Sigurðar

[edit]Frá dauða Sigurðar is a short prose text between the songs. The text mentions that, although the previous song said that Sigurd was killed in the forest, other songs say he was murdered in bed. German songs say that he was killed in the forest, but the next song in the codex, Guðrúnarqviða in fursta, says that he was killed while going to a thing.[88]

Sigurðarkviða hin skamma

[edit]In Sigurðarkviða hin skamma, Sigurd comes to the court of Gjuki and he, Gunnar, and Högni swear friendship to each other. Sigurd marries Gudrun, then acquires Brynhild for Gunnar and does not sleep with her. Brynhild desires Sigurd, however, and when she cannot have him decides to have him killed. Guthorm then slays Sigurd in his bed, but Sigurd kills him before dying. Brynhild then kills herself and asks to be burned on the same pyre as Sigurd.[89]

The poem is generally assumed not to be very old.[87]

Völsunga saga

[edit]

The Völsunga saga is the most detailed account of Sigurd's life in either the German or Scandinavian traditions besides the Poetic Edda.[90] It follows the plot given in the Poetic Edda fairly closely, although there is no indication that the author knew the other text.[91] The author appears to have been working in Norway and to have known the Thidrekssaga, and therefore the Völsunga Saga is dated to sometime in the second half of the 13th century.[92] The saga changes the geographic location of Sigurd's life from Germany to Scandinavia.[93] The saga is connected to a second saga, Ragnars saga Loðbrókar, which follows it in the manuscript, by having Ragnar Lodbrok marry Aslaug, daughter of Sigurd and Brynhild.[94]

According to the Völsunga saga, Sigurd is the posthumous son of King Sigmund and Hjordis. He died fighting Lyngvi, a rival for Hjordis's hand. Hjordis was left alone on the battlefield where Sigmund died, and was found there by King Alf, who married her and took Sigmund's shattered sword. She gave birth to Sigurd soon afterwards, who was raised by the smith Regin at the court of King Hjalprek. One day Regin tells Sigurd the story of a hoard guarded by the dragon Fafnir, which had been paid by Odin, Loki, and Hoenir for the death of Ótr. Sigurd asks Regin to make him a sword to kill the dragon, but each sword that Regin makes breaks when Sigurd proofs them against the anvil. Finally, Sigurd has Regin make a new sword out of Sigmund's shattered sword, and with this sword he is able to cut through the smith's anvil. Regin asks Sigurd to retrieve Regin's part of Fafnir's treasure, but Sigurd decides to avenge his father first. With an army he attacks and kills Lyngvi, receiving the help of Odin.[95]

Then Sigurd heads to Gnita-Heath to kill the dragon, hiding in a pit that Fafnir will travel over. Sigurd stabs Fafnir through the heart from underneath, killing him. Regin then appears, drinks some of the dragon's blood, and tells Sigurd to cook its heart. Sigurd tests with his finger whether the heart is done and burns himself; he sticks his finger in his mouth and can understand the language of the birds. The birds tell him that Regin plans to kill Sigurd and that he would be wiser to kill Regin first and then take the hoard and go to Brynhild. Sigurd does all of this, coming to where Brynhild lies asleep in a ring of shields and wearing armor that seems to have grown to her skin. Sigurd cuts the armor off her, waking Brynhild. Brynhild and Sigurd promise to marry each other, repeating their promise also at the court of Brynhild's brother-in-law Heimir.[96]

Sigurd then comes to the court of King Gjuki; queen Grimhild gives him a potion so that he forgets his promise to Brynhild and agrees to marry her daughter Gudrun. Sigurd and Gjuki's sons Gunnar and Högni swear an oath of loyalty to each other and become blood brothers.[97] Meanwhile, Grimhild convinces Gunnar to marry Brynhild, which Brynhild's family agrees to. However, Brynhild will only marry Gunnar if he can cross the wall of fire that surrounds her castle. Gunnar is unable to do this, and Sigurd and Gunnar use a spell taught to them by Grimhild to change shapes. Sigurd then crosses the wall of flames, and Brynhild is astonished that anyone but Sigurd was able to perform this task. Sigurd then lies with Brynhild for three nights with a sword placed between them.[98] Brynhild and Gunnar and Sigurd and Gudrun then marry on the same day.[97]

One day, Gudrun and Brynhild fight while bathing in the river over which of them has married the noblest man, and Gudrun tells Brynhild how she was tricked and shows her a ring that Sigurd had taken from her on her first night of marriage as proof. Brynhild is furious and wants revenge. When Sigurd goes to talk to her, the two confess their love for each other and Sigurd proposes divorcing Gudrun to be with Brynhild. Brynhild refuses, and later demands that Gunnar kill Sigurd. Gunnar tells his younger brother Guthorm to kill Sigurd, because he has never sworn loyalty to Sigurd. Guthorm, having eaten wolf's flesh, forces his way into Sigurd's bedchamber and stabs him in the back with his sword. Sigurd manages to kill Guthorm, assures Gudrun that he has always been loyal to Gunnar, and dies. Brynhild commits suicide soon afterwards, and she and Sigurd are both burned on the same pyre.[99]

Ballads

[edit]The Scandinavian Sigurd tradition lived on in a number of ballads, attested from across the Nordic area. They often have very little in common with the original traditions, only using names found there.[100]

Denmark and Sweden

[edit]Several Danish ballads (Danish folkevise) feature Sigurd (known as Sivard); some also exist in Swedish variants. These ballads appear to have had both Scandinavian and German sources.[101]

In the ballad Sivard Snarensvend (DgF 2, SMB 204, TSB E 49), Sigurd kills his stepfather and rides, with great difficulty, the unbroken horse Gram to his uncle in Bern. In one variant, the ballad ends when Sigurd falls from the horse and dies after jumping over the city walls.[102]

In the ballad Sivard og Brynild (DgF 3, TSB E 101), Sigurd wins Brynhild on the "glass mountain" and then gives her to his friend Hagen. Brynhild then fights with Sigurd's wife Signild, and Signild shows Brynhild a ring that Brynhild had given Sigurd as a love gift. Brynhild then tells Hagen to kill Sigurd, and Hagen does this by first borrowing Sigurd's sword then killing him with it. He then shows Brynhild Sigurd's head and kills her too when she offers him her love.[103]

In the ballad Kong Diderik og hans Kæmper (DgF 7, SMB 198, TSB E 10), Sigurd fights against Diderik's warrior Humlung. Sigurd defeats Humlung, but discovering that Humlung is his relative allows himself to be tied to an oak tree so that Humlung can claim to have defeated him. When Vidrek (Witege) doesn't believe Humlung and goes to check, Sigurd rips the oak tree from the ground and walks home with it on his back.[104]

In the ballad Kong Diderik og Løven (DgF 9, TSB E 158), Sigurd (here as Syfred) is said to have been killed by a dragon;[105] Svend Grundtvig suggests that this character corresponds to Ortnit, rather than Sigurd.[106]

Norway

[edit]The Norwegian ballad of "Sigurd Svein" (NMB 177, TSB E 50) tells of Sigurd's selection of the horse Grani and his ride to Greip (Grípir). Although the ballad has many archaic features, it is first recorded in the middle of the 19th century.[107]

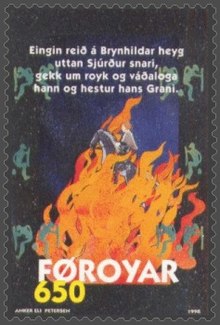

Faroe Islands

[edit]

On the Faroe Islands, ballads about Sigurd are known as Sjúrðar kvæði (CCF 1; Sjúrður is the Faroese form of Sigurd); these ballads contain material from the Thidrekssaga and the Völsunga saga.[101] The original form of the ballads likely dates to the 14th century,[101] though it is clear that many variants have been influenced by the Danish ballads.[108] The Faroese ballads include Regin smiður (Regin the Smith, TSB E 51), Brynhildar táttur (the song of Brynhild, TSB E 100), and Høgna táttur (the song of Högni, TSB E 55 and E 38). It is possible that Regin smiður is based on a lost Eddic poem.[101] The Faroese ballads include Sigurd's slaying of the dragon and acquiring of the hoard, his wooing of Gudrun and Brynhild, and his death.[109] They were not recorded until the end of the 18th century.[107]

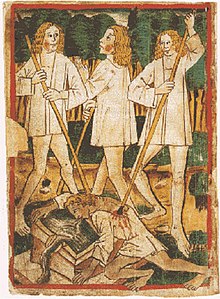

Pictorial depictions

[edit]There are a number of proposed or confirmed depictions of Sigurd's youthful adventures in Scandinavia and on the British Isles in areas under Norse influence or control. Many of the oldest depictions are very unclear however, and their depiction of the Sigurd legend is often disputed.[110] Attempts to identify depictions of the Sigurd story in Sangüesa (the "Spanish Sigurd"), in Naples (the "Norman Sigurd"), and in northern Germany have all been refuted.[111] There are also no confirmed depictions from Denmark.[111]

Sigurd's killing of Fafnir can be iconographically identified by his killing of the dragon from below, in contrast to other depictions of warriors fighting dragons and other monsters.[111]

Surviving depictions of Sigurd are frequently found in churches or on crosses; this is likely because Sigurd's defeat of the dragon was seen as prefiguring Christ's defeat of Satan.[112] It is also possible that he was identified with the Archangel Michael, who also defeated a dragon and played an important role in the Christianization of Scandinavia.[113]

Sweden

[edit]

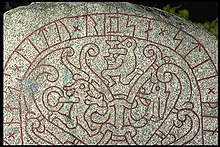

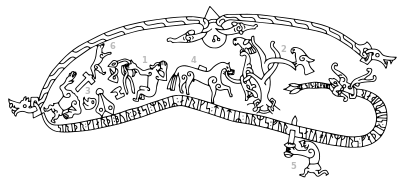

The Swedish material consists mostly of runestones which can be tentatively dated to the 11th century.[114] The earliest of these are from Södermanland, the Ramsund carving and the Gök runestone, which appears to be a copy of the former.[115] The stones depict Sigurd killing Fafnir, Regin's headless body surrounded by his smithing tools, Sigurd cooking Fafnir's heart, and the birds advising Sigurd above Grani.[115]

Two more depictions come from Uppland, the Drävle runestone and a copy of it, the Storja Ramsjö runestone. Both show Sigurd killing Fafnir.[116]

Three further depictions come from Gästrikland, the Årsund runestone, the Ockelbo runestone, which has been lost, and the Öster-Färnebo runestone. Sigurd is depicted stabbing Fafnir so that his sword takes the appearance of a u-rune. Other scenes on the runestones cannot be identified with the Sigurd legend securely, and the text on the stones is unrelated.[117][118]

British Isles

[edit]

Four fragmentary crosses from the Isle of Man, from Kirk Andreas, Malew, Jurby, and Maughold depict Sigurd stabbing Fafnir from underneath. The crosses also depict the cooking of Fafnir's heart, Sigurd receiving advice from the birds, and potentially his horse Grani.[119] These crosses possibly date to around 1000.[120]

There are also a number of depictions from England, likely dating from the period of Norse rule between 1016 and 1042.[121] In Lancashire, the Heysham hogback may depict Sigurd stabbing Fafnir through the belly as well as his horse Grani. It is one of the few monuments on the British Isles that does not appear to have been influenced by Christianity.[122] The nearby Halton cross appears to depict Regin forging Sigurd's sword and Sigurd roasting Fafnir's heart, sucking his thumb.[123] The iconography of these depictions resembles that found on the Isle of Man.[122]

In Yorkshire, there are at least three further depictions: a cross fragment at Ripon Cathedral, a cross built into a church at Kirby Hill, and a lost fragment from Kirby Hill that is preserved only as a drawing. The first two attestations depict Sigurd with his finger in his mouth while cooking Fafnir's heart, while the third may depict Fafnir with a sword in his heart.[124] There is also a badly worn gravestone from York Minster that appears to show Regin after having been beheaded and Sigurd with his thumb in his mouth, along with possibly Grani, the fire, and the slain Fafnir.[125]

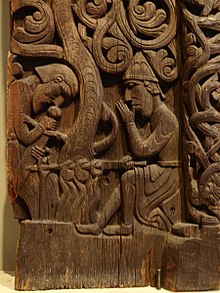

Norway

[edit]Numerous Norwegian churches from the late twelfth and early 13th centuries depict scenes from the Sigurd story on their front portals.[126] The most famous of these is the Hylestad Stave Church, likely from around 1200.[127] It shows numerous scenes from Sigurd's legend: Regin is shown in his smithy, Sigurd fights against and kills the dragon, cooks its heart and sucks his burnt thumb, receives the advice of the birds, kills Regin.[128] The most complete sequence is found in the Vegusdal stave church.[120] In some of the depictions, Sigurd appears beside Old Testament heroes such as Samson (stave churches at Lund and Nes).[129]

There are also two older stone carvings from Norwegian churches depicting Sigurd killing Fafnir.[130]

Theories about the development of the Sigurd figure

[edit]

It is difficult to trace the development of the traditions surrounding Sigurd. If the theory that he has his origins in Sigebert I is correct, then the earliest part of the tradition would be his murder as the result of a feud between two women, in real life between his wife Brunhild of Austrasia and Fredegund, in the saga then between his wife Kriemhild/Gudrun and Brünhild/Brynhild.[17] The earliest attested tradition about Sigurd is his slaying of a dragon, however, which supports the notion that he may have a purely mythological origin,[25] or that he represents the combination of a mythological figure with a historical one.[27]

Relationship to Sigmund and the Völsungs

[edit]It is unclear whether Sigurd's descent from the god Odin via Völsung, described only in the Völsunga saga, represents an old common tradition, or whether it is a development unique to the Scandinavian material.[131] Anglo-Saxon, Frankish, and other West Germanic royal genealogies often begin with Wodan or some other mythical ancestor such as Gaut, meaning that it is certainly possible that Sigurd's divine descent is an old tradition.[131][132] Wolfgang Haubrichs notes that the genealogy of the Anglo-Saxon kings of Deira has a similar prevalence of names beginning with the element Sigi- and that the first ancestor listed is Wodan.[133]

Sigurd's relationship to Sigmund, attested as Sigurd's father in both the continental and Scandinavian traditions, has been interpreted in various ways. Notably, references to Sigurd in Scandinavia can only be dated to the 11th-century, while references to Sigmund in Scandinavia and England, including in Beowulf, can be dated earlier.[134] It is possible that Sigmund's parentage is a later development, as the Scandinavian tradition and the German tradition represented by Hürnen Seyfrid[135] locate Sigurd's childhood in the forest and show him to be unaware of his parentage.[136] Catalin Taranu argues that Sigurd only became Sigmund's son to provide the orphan Sigurd with a suitable heroic past.[137] This may have occurred via the story that Sigurd has to avenge his father's death at the hands of the sons of Hunding.[138]

The Old English tradition of Sigemund (Sigmund) complicates things even more: in Beowulf Sigmund is said to have slain a dragon and won a hoard. This may be a minor variant of the Sigurd story,[139] or it is possible that the original dragon slayer was Sigmund, and the story was transferred from father to son.[140] Alternatively, it is possible that Sigurd and Sigmund were originally the same figure, and were only later split into father and son. John McKinnell argues that Sigurd only became the dragon-slayer in the mid-11th century.[141] Hermann Reichert, on the other hand, argues that the two dragon-slayings are originally unrelated: Sigurd kills one when he is young, which represents a sort of heroic initiation, whereas Sigmund kills a dragon when he is old, which cannot be interpreted in this way. In his view, this makes an original connection between or identity of the two slayings unlikely.[142]

Sigurd's youth

[edit]The slaying of the dragon is attested on the 11th-century Ramsund carving in Sweden, and the Gök Runestone, which appears to be a copy of the carving. Both stones depict elements of the story identifiable from the later Norse myths.[115] In both the German and the Scandinavian versions, Sigurd's slaying of the dragon embues him with superhuman abilities. In the Norse sources, Sigurd comes to understand the language of the birds after tasting the dragon's blood and then eating its heart. In the German versions, Siegfried bathes in the dragon's blood, developing a skin that is as hard as horn (Middle High German hürnen).[143][144]

In the continental sources, Sigurd's winning of the hoard of the Nibelungen and slaying of the dragon are two separate events; the Thidrekssaga does not even mention Sigurd's acquiring the hoard.[72] In the Norse tradition, the two events are combined and Sigurd's awakening of Brunhild and avenging of his father are also mentioned, though not in all sources. It is likely that the Norse tradition has substantially reworked the events of Sigurd's youth.[72] Sigurd's liberation of a virgin woman, Brynhild/Brünhild, is only told in Scandinavian sources, but may be an original part of the oral tradition along with the slaying of the dragon, since the Nibelungenlied seems to indicate that Siegfried and Brünhild already know each other.[145] This is not entirely clear, however.[146] It is possible that Siegfried's rescue of Kriemhild (rather than Brünhild) in the late-medieval Lied vom Hürnen Seyfrid reflects the tradition that Sigurd liberated a virgin.[147][148]

The origin of the hoard as a cursed ransom paid by the gods is generally taken to be a late and uniquely Scandinavian development.[149][150]

Also attested on the Ramsund Carving, and thus at an early date, is that Sigurd was raised by a smith.[115] While absent in the Nibelungenlied, the Rosengarten and late-medieval Lied vom Hürnen Seyfrid show that this tradition was present in Germany as well.[151]

The death of Sigurd and connection to the Burgundians

[edit]On the basis of the poem Atlakviða it is generally believed that Sigurd was not originally connected to the story of the destruction of the Burgundians by Attila (Old Norse Atli, Middle High German Etzel).[152] The earliest text to make this connection is the Nibelungenlied (c. 1200); the combination appears to be older, but it is difficult to say by how much.[153] In the German tradition, this connection led to the change of the role of Sigurd's widow from avenger of her brothers to avenger of her husband on her brothers, again, sometime before the composition of the Nibelungenlied.[154][155]

Modern reception

[edit]

Siegfried remained a popular figure in Germany via Das Lied vom Hürnen Seyfrid and its prose version, the Historia vom gehörnten Siegfried, the latter of which was still printed in the 19th century.[61] The prose version was popular enough that in 1660 a sequel was written about Siegfried's son with "Florigunda" (Kriemhild), Löwhardus.[156] The Nibelungenlied, on the other hand, was forgotten until it was rediscovered in 1755.[157]

The majority of the Scandinavian material about Sigurd remained better known through the early modern period to the 19th century due to the so-called "Scandinavian Renaissance", which resulted in knowledge of Eddic poems influencing the popular ballads about Sigurd in Scandinavian folklore.[100][158]

Originally, modern reception of Siegfried in Germany was dominated by a sentimental view of the figure, shown in the many paintings and images produced in this time depicting Siegfried taking leave from Kriemhild, the first encounter of Siegfried and Kriemhild, their wedding, etc.[159] A nationalist tone and attempt to make Siegfried into a national icon and symbol was nevertheless already present in attempts to connect Siegfried to the historical Arminius, who was already established as a national hero in Germany since the 16th century.[160][161] The Norse tradition about Sigurd, which was considered to be more "original" and Germanic, in many ways replaced direct engagement with the German Nibelungenlied, and was highly influential in the conception of the Siegfried figure in Richard Wagner's opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen (1874).[162] Wagner's portrayal of Siegfried was to influence the modern public's view of the figure immensely.[163]

With the founding of the German Empire (1871), the German view of Siegfried became more nationalistic: Siegfried was seen as an identifying epic figure for the new German Empire and his reforging of his father's sword in the Nordic tradition was equated with Otto von Bismarck "reuniting" the German nation.[163] Numerous paintings, monuments, and fountains of Siegfried date from this time period.[164] Following the defeat of imperial Germany in the First World War, Siegfried's murder by Hagen was extensively used in right-wing propaganda that claimed that leftist German politicians had stabbed the undefeated German army in the back by agreeing to an armistice.[163] This comparison was explicitly made by Adolf Hitler in Mein Kampf and by Paul von Hindenburg in his political testament.[165] Nazi propaganda came to use Siegfried "to symbolize the qualities of healthy and virile German men."[164] Siegfried's murder by Hagen was further used to illustrate Nazi racial theories about the inherent evilness of certain "non-German" races, to which Hagen, typically depicted as dark, was seen as belonging.[166]

Outside of Germany and Scandinavia, most of the reception of Sigurd has been mediated through, or at least influenced by, his depiction in Wagner's Ring.[167]

Notable adaptations of the legend

[edit]- The best-known adaptation of the Sigurd legend is Richard Wagner's cycle of music dramas Der Ring des Nibelungen (written between 1848 and 1874). The Sigurd legend is the basis of Siegfried and contributes to the stories of Die Walküre and Götterdämmerung.[citation needed]

- William Morris's epic poem Sigurd the Volsung (1876) is a major retelling of the story in English verse.[citation needed]

- In 1884 the French composer Ernest Reyer wrote the lesser-known opera Sigurd, which condenses the story into a single evening's drama.[citation needed]

- James Baldwin retold the story in a work intended for older children, The Story of Siegfried (1905).[citation needed]

- Fritz Lang and his then-wife Thea von Harbou adapted the story of Sigurd (called Siegfried) for the first part of their 1924 pair of silent films Die Nibelungen. The two films are primarily based on the Nibelungenlied, but also include Norse stories about Siegfried's youth.[citation needed]

- J. R. R. Tolkien wrote his version of the Volsunga saga in The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún about 1930, published posthumously by his son Christopher Tolkien in 2009. The book comprises two narrative poems: "The new lay of the Volsungs" and "The new lay of Gudrun". They are in Modern English, but the meter is that of ancient Scandinavian alliterative poetry.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Sigebert I

- Siegfried Line

- Siegfried (opera)

- Sigurd (opera)

- Arminius

- Achilles, a similarly invulnerable warrior from Greek myth with a single mortal weakness that resulted in his downfall

- Duryodhana, a similarly invulnerable warrior with a single mortal weakness from the Sanskrit epic, the Mahabharatha

- Esfandiyar, a similarly invulnerable warrior with a single mortal weakness from the Persian epic, the Shahnameh

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Höfler argued Arminius's Germanic name may have been *Segi-friþuz.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Lienert 2015, p. 30.

- ^ Haymes 1988, p. 214.

- ^ a b c d Gillespie 1973, p. 122.

- ^ Reichert 2008, p. 143.

- ^ Gentry et al. 2011, p. 114.

- ^ Haustein 2005.

- ^ Uecker 1972, p. 46.

- ^ Heinrichs 1955–1956, p. 279.

- ^ Reichert 2008, pp. 148–151.

- ^ a b c Müller 2009, p. 22.

- ^ Haubrichs 2000, pp. 201–202.

- ^ a b Haubrichs 2000, p. 202.

- ^ Reichert 2008, pp. 141–147.

- ^ Reichert 2008, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Gillespie 1973, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Fichtner 2004, p. 327.

- ^ a b Haymes & Samples 1996, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Fichtner 2004, p. 329.

- ^ a b c Haustein 2005, p. 380.

- ^ Byock 1990, p. 25.

- ^ Fichtner (2015), p. 383.

- ^ a b Lee 2007, pp. 397–398.

- ^ Höfler 1961.

- ^ Gallé 2011, p. 9.

- ^ a b Millet 2008, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Müller 2009, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Taranu 2015, p. 24.

- ^ Gentry et al. 2011, p. 103, 139.

- ^ Heinzle 1981–1987, p. 4: "Seifrid ein kúnig auß nyderland / des was das land vmbe wurms. vnd lag nache bey kúnig Gibich lant".

- ^ Lienert 2015, p. 38.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Lienert 2015, p. 39.

- ^ Heinzle 2013, p. 1240.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Heinzle 2013, pp. 1240–1241, 1260.

- ^ Heinzle 2013, pp. 1289–1293.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 361–363.

- ^ Lienert 2015, pp. 134–136.

- ^ Haymes & Samples 1996, p. 128.

- ^ Lienert 2015, p. 134.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 364–365.

- ^ Gillespie 1973, p. 34.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 270–273.

- ^ Gillespie 1973, p. 121, n. 4.

- ^ Haymes 1988, p. 100.

- ^ Haymes 1988, p. 104.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 263–264.

- ^ Haymes & Samples 1996, p. 114.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 264.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 266.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 273–274.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 271–272.

- ^ Haymes 1988, pp. xxvii–xxix.

- ^ Gentry et al. 2011, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Gentry et al. 2011, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 372.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 373–374.

- ^ Lienert 2015, p. 147.

- ^ Gentry et al. 2011, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 367.

- ^ a b Lienert 2015, p. 67.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 466–471.

- ^ Grimm 1867, p. 42.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 487.

- ^ Grimm 1867, p. 304.

- ^ Lienert 2015, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 308–309.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 291.

- ^ Gentry et al. 2011, p. 12.

- ^ Haymes & Samples 1996, p. 127.

- ^ a b c Sprenger 2000, p. 126.

- ^ Sturluson 2005, p. 97.

- ^ Sturluson 2005, pp. 97–100.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 288.

- ^ a b Millet 2008, p. 294.

- ^ Edwards, Cyril (trans.) (2010). The Nibelungenlied. The Lay of the Nibelungs. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-19-923854-5.

- ^ Haymes & Samples 1996, p. 119.

- ^ Larrington 2014, p. 138.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 295.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 295–296.

- ^ a b Würth 2005, p. 424.

- ^ Würth 2005, p. 425.

- ^ Sprenger 2000, pp. 127–128.

- ^ a b c Millet 2008, p. 296.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 296–297.

- ^ a b Würth 2005, p. 426.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 297.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 297–298.

- ^ Gentry et al. 2011, p. 120.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 319.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 313.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 321–322.

- ^ Haymes & Samples 1996, p. 116.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 314–315.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 315.

- ^ a b Gentry et al. 2011, p. 121.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 315–316.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 316.

- ^ a b Millet 2008, p. 477.

- ^ a b c d Böldl & Preißler 2015.

- ^ Holzapfel 1974, p. 39.

- ^ Holzapfel 1974, p. 65.

- ^ Holzapfel 1974, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Holzapfel 1974, p. 197.

- ^ Svend Grundtvig (1853). Danmarks gamle folkeviser (in Danish). Vol. 1. Samfundet til den Danske Literaturs Fremme. pp. 82–83. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ a b Holzapfel 1974, p. 29.

- ^ Holzapfel 1974, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Holzapfel 1974, p. 28.

- ^ Düwel 2005, p. 413.

- ^ a b c Düwel 2005, p. 420.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 168.

- ^ Düwel 2005, p. 114-115.

- ^ a b c d Millet 2008, p. 163.

- ^ Düwel 2005, p. 415.

- ^ Düwel 2005, pp. 416–417.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Düwel 2005, p. 414.

- ^ a b Millet 2008, p. 160.

- ^ McKinnell 2015, p. 66.

- ^ a b McKinnell 2015, p. 61.

- ^ McKinnell 2015, p. 62.

- ^ McKinnell 2015, pp. 62–64.

- ^ McKinnell 2015, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Düwel 2005, pp. 418–422.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 155.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 167.

- ^ Düwel 2005, p. 418.

- ^ a b Haymes & Samples 1996, p. 166.

- ^ Haubrichs 2000, pp. 197–200.

- ^ Haubrichs 2000, p. 198-199.

- ^ Taranu 2015, pp. 24–27.

- ^ Lienert 2015, p. 68.

- ^ Gillespie 1973, p. 126.

- ^ Taranu 2015, p. 32.

- ^ Uecker 1972, p. 26.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 78.

- ^ Uecker 1972, p. 24.

- ^ McKinnell 2015, p. 73.

- ^ Reichert 2008, p. 150.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 166.

- ^ Gentry et al. 2011, p. 147.

- ^ Heinzle 2013, p. 1009.

- ^ Gentry et al. 2011, p. 116.

- ^ Gentry et al. 2011, p. 169.

- ^ Gillespie 1973, p. 16 n. 8.

- ^ Lienert 2015, p. 31.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 165.

- ^ Gentry et al. 2011, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Lienert 2015, p. 35.

- ^ Heinzle 2013, pp. 1009–1010.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 471.

- ^ Lienert 2015, p. 189.

- ^ Holzapfel 1974, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Müller 2009, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Gallé 2011, pp. 22.

- ^ Lee 2007, pp. 297–298.

- ^ Lienert 2015, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Müller 2009, p. 183.

- ^ a b Lee 2007, p. 301.

- ^ Gentry et al. 2011, p. 306.

- ^ Lee 2007, pp. 301–302.

- ^ Gentry et al. 2011, p. 222.

General references

[edit]- Böldl, Klaus; Preißler, Katharina (2015). "Ballade". Germanische Altertumskunde Online. Berlin, Boston: de Gruyter.

- Byock, Jesse L. (trans.) (1990). The Saga of the Volsungs: The Norse Epic of Sigurd the Dragon Slayer. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California. ISBN 0-520-06904-8.

- Düwel, Klaus (2005). "Sigurddarstellung". In Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Vol. 28. New York/Berlin: de Gruyter. pp. 412–422.

- Fichtner, Edward G. (2004). "Sigfrid's Merovingian Origins". Monatshefte. 96 (3): 327–342. doi:10.3368/m.XCVI.3.327. S2CID 219196272.

- Fichtner, Edward G. (Fall 2015). "Constructing Sigfrid: History and Legend in the Making of a Hero". Monatshefte. 107 (3): 382–404. doi:10.3368/m.107.3.382. JSTOR 24550296. S2CID 162544840.

- Gallé, Volker (2011). "Arminius und Siegfried – Die Geschichte eines Irrwegs". In Gallé, Volker (ed.). Arminius und die Deutschen : Dokumentation der Tagung zur Arminiusrezeption am 1. August 2009 im Rahmen der Nibelungenfestspiele Worms. Worms: Worms Verlag. pp. 9–38. ISBN 978-3-936118-76-6.

- Gentry, Francis G.; McConnell, Winder; Müller, Ulrich; Wunderlich, Werner, eds. (2011) [2002]. The Nibelungen Tradition. An Encyclopedia. New York, Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-8153-1785-2.

- Gillespie, George T. (1973). Catalogue of Persons Named in German Heroic Literature, 700-1600: Including Named Animals and Objects and Ethnic Names. Oxford: Oxford University. ISBN 978-0-19-815718-2.

- Grimm, Wilhelm (1867). Die Deutsche Heldensage (2nd ed.). Berlin: Dümmler. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- Haubrichs, Wolfgang (2000). ""Sigi"-Namen und Nibelungensage". In Chinca, Mark; Heinzle, Joachim; Young, Christopher (eds.). Blütezeit: Festschrift für L. Peter Johnson zum 70. Geburtstag. Tübingen: Niemeyer. pp. 175–206. ISBN 3-484-64018-9.

- Haustein, Jens (2005). "Sigfrid". In Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Vol. 28. New York/Berlin: de Gruyter. pp. 380–381.

- Haymes, Edward R. (trans.) (1988). The Saga of Thidrek of Bern. New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8240-8489-6.

- Haymes, Edward R.; Samples, Susan T. (1996). Heroic legends of the North: an introduction to the Nibelung and Dietrich cycles. New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8153-0033-6.

- Heinrichs, Heinrich Matthias (1955–1956). "Sivrit – Gernot – Kriemhilt". Zeitschrift für Deutsches Altertum und Deutsche Literatur. 86 (4): 279–289.

- Heinzle, Joachim, ed. (1981–1987). Heldenbuch: nach dem ältesten Druck in Abbildung herausgegeben. Göppingen: Kümmerle. (Facsimile edition of the first printed Heldenbuch (volume 1), together with commentary (volume 2))

- Heinzle, Joachim, ed. (2013). Das Nibelungenlied und die Klage. Nach der Handschrift 857 der Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen. Mittelhochdeutscher Text, Übersetzung und Kommentar. Berlin: Deutscher Klassiker Verlag. ISBN 978-3-618-66120-7.

- Höfler, Otto (1961). Siegfried, Arminius und die Symbolik: mit einem historischen Anhang über die Varusschlacht. Heidelberg: Winter.

- Holzapfel, Otto (Otto Holzapfel), ed. (1974). Die dänischen Nibelungenballaden: Texte und Kommentare. Göppingen: Kümmerle. ISBN 3-87452-237-7.

- Lee, Christina (2007). "Children of Darkness: Arminius/Siegfried in Germany". In Glosecki, Stephen O. (ed.). Myth in Early Northwest Europe. Tempe, Arizona: Brepols. pp. 281–306. ISBN 978-0-86698-365-5.

- Lienert, Elisabeth (2015). Mittelhochdeutsche Heldenepik. Berlin: Erich Schmidt. ISBN 978-3-503-15573-6.

- McKinnell, John (2015). "The Sigmundr / Sigurðr Story in an Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norse Context". In Mundal, Else (ed.). Medieval Nordic Literature in its European Context. Oslo: Dreyers Forlag. pp. 50–77. ISBN 978-82-8265-072-4.

- Millet, Victor (2008). Germanische Heldendichtung im Mittelalter. Berlin, New York: de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-020102-4.

- Müller, Jan-Dirk (2009). Das Nibelungenlied (3 ed.). Berlin: Erich Schmidt.

- Larrington, Carolyne (trans.) (2014). The Poetic Edda: Revised Edition. Oxford: Oxford University. ISBN 978-0-19-967534-0.

- Reichert, Hermann (2008). "Zum Namen des Drachentöters. Siegfried – Sigurd – Sigmund – Ragnar". In Ludwig, Uwe; Schilp, Thomas (eds.). Nomen et fraternitas : Festschrift für Dieter Geuenich zum 65. Geburtstag. Berlin: de Gruyter. pp. 131–168. ISBN 978-3-11-020238-0.

- Sprenger, Ulrike (2000). "Jungsigurddichtung". In Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Vol. 16. New York/Berlin: de Gruyter. pp. 126–129.

- Sturluson, Snorri (2005). The Prose Edda: Norse Mythology. Translated by Byock, Jesse L. New York, London: Penguin Books.

- Taranu, Catalin (2015). "Who Was the Original Dragon-slayer of the Nibelung Cycle?". Viator. 46 (2): 23–40. doi:10.1484/J.VIATOR.5.105360.

- Uecker, Heiko (1972). Germanische Heldensage. Stuttgart: Metzler. ISBN 3-476-10106-1.

- Uspenskij, Fjodor. 2012. The Talk of the Tits: Some Notes on the Death of Sigurðr Fáfnisbani in Norna Gests þáttr. The Retrospective Methods Network (RMN) Newsletter: Approaching Methodology. No. 5, December 2012. Pp. 10–14.

- Würth, Stephanie (2005). "Sigurdlieder". In Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Vol. 28. New York/Berlin: de Gruyter. pp. 424–426.

External links

[edit] Media related to Siegfried at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Siegfried at Wikimedia Commons- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.