Tell Kazel

تل كزل | |

| Region | Tartus Governorate |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 34°42′29″N 35°59′10″E / 34.708056°N 35.986111°E |

| Type | Tell |

| Part of | Ancient city |

| Length | 350 m |

| Width | 325 m |

| Area | 11 ha (27 acres) |

| History | |

| Material | Stone, flints, pottery |

| Periods | Bronze Age |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1956, 1960–1968, 1985-2001 |

| Archaeologists | Maurice Dunand, Nassib Saliby, ‘Adnān Bounnī, Leila Badre, Assaad Seif |

| Condition | Ruins |

| Management | Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums |

| Public access | Yes |

Tell Kazel (Arabic: تل الكزل, romanized: Tall al-Kazil) is an oval-shaped tell that measures 350 m × 325 m (1,150 ft × 1,070 ft) at its base, narrowing to 200 m × 200 m (660 ft × 660 ft) at its top. It is located in the Safita district of the Tartus Governorate in Syria in the north of the Akkar plain on the north of the al-Abrash River approximately 18 km (11 mi) south of Tartus.[1]

Links to ancient Sumur

[edit]The tell was first surveyed in 1956 after which a lengthy discussion was opened by Maurice Dunand and Nassib Saliby identifying the site with the ancient city variously named Sumur, Simyra or Zemar (Egyptian Smr Akkadian Sumuru or Assyrian Simirra).[1] The ancient city is mentioned in the Bible, Book of Genesis (Genesis 10:18) and 1 Chronicles (1 Chronicles 1:16) as the home of the Zemarites, an offshoot of the Caananites.[2] It was a major trade center and appears in the Amarna letters; Ahribta is named as its ruler. It was under the guardianship of Rib-Hadda, king of Byblos, but revolted against him and joined Abdi-Ashirta's expanding kingdom of Amurru. Pro-Egyptian factions may have seized the city again but Abdi-Ashirta's son Aziru recaptured the city.

Archaeology

[edit]

The site was surveyed in 1956.[3] The tell was first excavated between 1960 and 1962 by Maurice Dunand, Nassib Saliby and Adnān Bounni who determined a sequence between the Middle Bronze Age through to the Hellenistic civilization.[4] The most important occupations were determined to have taken place during the Late Bronze Age and Persian Empire.[1]

In 1985, new excavations began in partnership between the Archaeological Museum of the American University of Beirut and the Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums in Syria under the directorship of Leila Badre. Excavations continued for 18 seasons until 2001.[5][6][7]

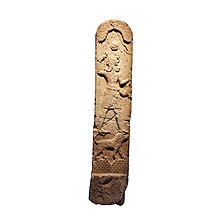

A large amount of imported pottery from Cyprus, known as Cypriot bichrome ware, was found dating between the 14th and 12th centuries BC and contrasting to other sites in the Homs gap. The city was destroyed during the Late Bronze Age, after which local Mycenaean ceramics, Handmade burnished ware and Grey ware replaced the imported pottery.[1] Architectural remains at the site include a palace complex and temple that were dated towards the end of the Late Bronze Age. The temple contained a variety of amulets, seals and glazed ware that showed similarities with the culture of Ugarit. A later Iron Age settlement was detected between the 9th and 8th centuries BC which was brought to an end with evidence of burnt destruction caused by a currently unidentified Assyrian invasion.[8]

A warehouse and defensive installation made out of ashlar blocks were found dating to the Persian period with further evidence of Hellenistic occupation evidenced by a large cemetery in the northeast of the site.[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Badre, Leila., "Tell Kazel-Simyra: A Contribution to a Relative Chronological History in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Late Bronze Age", BASOR 343, pp. 65–95, 2006

- ^ Badre, L., Gubel, E., al-Maqdissi, M. and Sader, H., "Tell Kazel, Syria. Excavations of the AUB Museum, 1985–1987. Preliminary Reports", Berytus 38, pp. 9–124, 1990

- ^ Dunand, M., and Saliby, N., "A la recherche de Simyra", Annales archaeologiques de Syrie 7, pp. 3-16, 1957

- ^ Dunand, Maurice, Bounni, A. and Saliby, N., "Fouilles de Tell Kazel: Rapport préliminaire", AAAS 14, pp. 3–22, 1964.

- ^ Badre, Leila., "Tell Kazel. Rapport Préliminaire sur les 4ème-8ème Campagnes de Fouilles (1988–1992)", Syria 71, pp. 259–359, 1994

- ^ Badre, L. and Gubel, E., "Tell Kazel, Syria. Excavations of the AUB Museum, 1993–1998. Third Preliminary Report", Berytus 44, pp. 123–203, 1999–2000

- ^ Capet, E., "Tell Kazel (Syrie). Rapport préliminaire sur les 9e-17e campagnes de fouilles (1993–2001) du musée de l'Université américaine de Beyrouth. Chantier II", Berytus 47, pp. 63–121, 2003

- ^ a b Glenn Markoe (2000). Phoenicians. University of California Press. pp. 205–. ISBN 978-0-520-22614-2. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

Further reading

[edit]- Badre, Leila., "Beirut and Tell Kazel: Two New Late Bronze Age Temples", in Proceedings of the First International Congress of Near Eastern Archaeology, 2001

- Badre, Leila., "Handmade Burnished Ware and Contemporary Imported Pottery from Tell Kazel", in Stampolidis, N.Ch. and Karageorghis, V. (eds), Sea Routes ... Interconnections in the Mediterranean 16th-6th Centuries BC. Proceedings of the International Symposium held at Rethymnon, Crete, in September 29-October 2, 2002, Athens, pp. 83–99, 2003

- Badre, L., Boileau, M.-C., Jung, R., Mommsen, H., "The Provenance of Aegean- and Syrian-Type Pottery Found at Tell Kazel (Syria)", Ä&L 15, pp. 15–47, 2005

- Elayi, Josette., "Les importations grecques à Tell Kazel (Symyra) à l'époque perse", AAAS 36-37, pp. 132–135, 1986–1987

- Michel Al-Maqdissi, "Prospection Autour de Tell Kazel En 1988", Syria, vol. 67, no. 2, pp. 462–63, 1990

- Sapin, Jean., "Archäologische und geographische Geländebegehung im Grabenbruch von Homs", AfO 26, pp. 174–176, 1978–1979

- Stieglitz, Robert R., "The Geopolitics of the Phoenician Littoral in the Early Iron Age", BASOR 279, pp. 9–12, 1990

- Stieglitz, Robert R., "The City of Amurru", JNES 50.1, pp. 45–48, 1991