Siachen conflict

| Siachen conflict | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Kashmir conflict | |||||||||

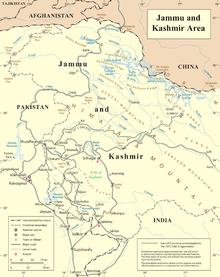

Labelled map of the greater Kashmir region; the Siachen Glacier lies in the Karakoram Range and its snout is situated less than 50 km (31 mi) north of the Ladakh Range | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 3,000+[5] | 3,000[5] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

The Siachen conflict, sometimes referred to as the Siachen Glacier conflict or the Siachen War, was a military conflict between India and Pakistan over the disputed 1,000-square-mile (2,600 km2)[13] Siachen Glacier region in Kashmir. The conflict was started in 1984 by India's successful capture of the Siachen Glacier as part of Operation Meghdoot, and continued with Operation Rajiv in 1987. India took control of the 70-kilometre-long (43 mi) Siachen Glacier and its tributary glaciers, as well as all the main passes and heights of the Saltoro Ridge immediately west of the glacier, including Sia La, Bilafond La, and Gyong La. Pakistan controls the glacial valleys immediately west of the Saltoro Ridge.[14][15][page needed] A cease-fire went into effect in 2003,[16] but both sides maintain a heavy military presence in the area. The conflict has resulted in thousands of deaths, mostly due to natural hazards.[17] External commentators have characterized it as pointless, given the perceived uselessness of the territory, and indicative of bitter stubbornness on both sides.[17]

Causes

The Siachen Glacier is the highest battleground on earth,[18][19] where India and Pakistan have fought intermittently since 13 April 1984. Both countries maintain a permanent military presence in the region at a height of over 6,000 metres (20,000 ft). More than 2000 people have died in this inhospitable terrain, mostly due to weather extremes and the natural hazards of mountain warfare.[citation needed]

The conflict in Siachen stems from the incompletely demarcated territory on the map beyond the map coordinate known as NJ9842 (35°00′30″N 77°00′32″E / 35.008371°N 77.008805°E). The 1949 Karachi Agreement and 1972 Simla Agreement did not clearly mention who controlled the glacier, merely stating that the Cease Fire Line (CFL) terminated at NJ9842.[20] UN officials presumed there would be no dispute between India and Pakistan over such a cold and barren region.[21][page needed]

Paragraph B 2 (d) of Karachi Agreement

Following the UN-mediated ceasefire in 1949, the line between India and Pakistan was demarcated up to point NJ9842 at the foot of the Siachen Glacier. The largely inaccessible terrain beyond this point was not demarcated,[20] but delimited as thence north to the glaciers in paragraph B 2 (d) of the Karachi Agreement.

Paragraph B 2 (d) of 1949 Karachi Agreement states:

(d) From Dalunang eastwards the cease-fire line will follow the general line point 15495, Ishman, Manus, Gangam, Gunderman, Point 13620, Funkar (Point 17628), Marmak, Natsara, Shangruti (Point 1,531), Chorbat La (Point 16700), Chalunka (on the Shyok River), Khor, thence north to the glaciers. This portion of the cease-fire line shall be demarcated in detail on the basis of the factual position as of 27 July 1949, by the local commanders assisted by United Nations military observers.

Later, following the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, and the Simla Agreement in July 1972, the ceasefire line was converted into the "Line of Control" extending from the "Chhamb sector on the international border [to] the Turtok-Partapur sector in the north."[20] The detailed description of its northern end stated that from Chimbatia in the Turtok sector "the line of control runs north-eastwards to Thang (inclusive to India), thence eastwards joining the glaciers." This vague formulation further sowed the seed for the bitter dispute to follow.[20]

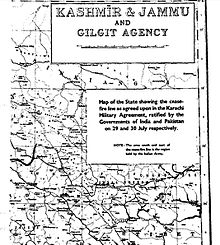

The UN document number S/1430/Add.2.[22] is the second addendum to the 1949 Karachi Agreement, and shows the CFL marked on the Map of the State of Jammu and Kashmir as per the explanation of CFL in paragraph 'B' 2 (d) of the Karachi Agreement.

U.N. map of ceasefire line

Title of UN document number S/1430/Add.2 which illustrates the CFL as per the Karachi Agreement reads:

Map of the State of Jammu and Kashmir showing the Cease Fire Line as Agreed Upon in the Karachi Agreement, Ratified by the Governments of India and Pakistan on 29 and 30 July Respectively. (See Annex 26 to the third Interim Report of the United Nation Commission for India and Pakistan)[23][24]

|

|

|

A UN map showing CFL alignment superimposed on a satellite image depicts the CFL terminating at NJ9842.[25] The extension of this line "thence north to the glaciers" never appeared on any authoritative map associated with either the 1948 or 1972 agreements, just in the text.

Oropolitics

In 1949, a Cease-Fire Line Agreement (CFL) was signed and ratified by India, Pakistan and the UN Military Observer Group that delineated the entire CFL. In 1956–58, a scientific team led by the Geological Survey of India recorded its findings publicly including information about the Siachen and other glaciers.[26]

After Pakistan ceded the 5,180 km2 (2,000 sq mi) Shaksgam Valley to China in a boundary agreement in 1963, Pakistan started giving approval to western expeditions to the east of mountain K2.[26] In 1957 Pakistan permitted a British expedition under Eric Shipton to approach the Siachen glacier through the Bilafond La, and recce Saltoro Kangri.[27][page needed] Five years later a Japanese-Pakistani expedition put two Japanese and a Pakistani Army climber on top of Saltoro Kangri.[28][page needed] These were early moves in this particular game of oropolitics.

In June 1958, first Geological Survey of India expedition went to the Siachen glacier.[29] It was the first official Indian survey of Siachen Glacier by Geological Survey of India post-1947 and that was undertaken to commemorate the International Geophysical Year in 1958. The study included snout surveying of five glaciers namely Siachen, Mamostong, Chong Kumdan, Kichik Kumdan and Aktash Glaciers in Ladakh region. 5Q 131 05 084 was the number assigned to the Siachen glacier by the expedition. In the 1970s and early 1980s several mountaineering expeditions applied to Pakistan to climb high peaks in the Siachen area due in part to US Defense Mapping Agency and most other maps and atlases showing it on the Pakistani side of the line. Pakistan granted a number of permits. This, in turn, reinforced the Pakistani claim on the area, as these expeditions arrived on the glacier with a permit obtained from the Government of Pakistan. Teram Kangri I (7,465 m or 24,491 ft) and Teram Kangri II (7,406 m or 24,298 ft) were climbed in 1975 by a Japanese expedition led by H. Katayama, which approached through Pakistan via the Bilafond La.[30][full citation needed]

In 1978 a German Siachen-Kondus Expedition under the leadership of Jaroslav Poncar (further members Volker Stallbohm and Wolfgang Kohl, liaison officer major Asad Raza) entered Siachen via Bilafond La and established the base camp on the confluence of Siachen and Teram Shehr. The documentary "Expedition to the longest glacier" was shown on the 3rd channel of WDR (German TV) in 1979.[31]

Prior to 1984 neither India nor Pakistan had any permanent presence in the area. Having become aware of US military maps and the permit incidents, Colonel Narendra Kumar, then commanding officer of the Indian Army's High Altitude Warfare School, mounted an Army expedition to the Siachen area as a counter-exercise. In 1978 this expedition climbed Teram Kangri II, claiming it as a first ascent in a typical "oropolitical" riposte. Unusually for the normally secretive Indian Army, the news and photographs of this expedition were published in The Illustrated Weekly of India, a widely circulated popular magazine.[32]

The first public acknowledgment of the maneuvers and the developing conflict situation in the Siachen was an abbreviated article titled "High Politics in the Karakoram" by Joydeep Sircar in The Telegraph newspaper of Calcutta in 1982.[33] The full text was re-printed as "Oropolitics" in the Alpine Journal, London, in 1984.[34][page needed]

Historic maps of Siachen Glacier

Maps from Pakistan, the United Nations and various global atlases depicted the CFL ending at NJ9842 until the mid 1960s.[26] United States Defense Mapping Agency (now National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency) began in about 1967 to show a boundary on their Tactical Pilotage Charts as proceeding from NJ9842 east-northeast to the Karakoram Pass at 5,534 m (18,136 ft) on the China border.[35] This line was replicated on US, Pakistani and other maps in the 1970s and 1980s,[36][37][38] which India believed to be a cartographic error.[32]

|

|

Military expeditions

In 1977, an Indian colonel named Narendra Kumar, offended by international expeditions venturing onto the glacier from the Pakistani side, persuaded his superiors to allow him to lead a 70-man team of climbers and porters to the glacier.[3] They returned in or around 1981, climbed several peaks and walked the length of Siachen.

Major combat operations

At army headquarters in Rawalpindi, the discovery of repeated Indian military expeditions to the glacier drove Pakistani generals to the idea of securing Siachen before India did. This operation was called Operation Ababeel. In the haste to pull together operational resources, Pakistan planners made a tactical error, according to a now-retired Pakistani army colonel. "They ordered Arctic-weather gear from a London outfitter who also supplied the Indians," says the colonel. "Once the Indians got wind of it, they ordered 300 outfits—twice as many as we had—and rushed their men up to Siachen". The acquisition of key supplies needed for operations in glaciated zones marked the start of major combat operations on the glacier.[5]

April 1984 Operation Meghdoot: Indian Army under the leadership of Lt. Gen. Manohar Lal Chibber, Maj. Gen. Shiv Sharma, and Lt. Gen. P. N. Hoon learned of the plan by Pakistan Army to seize Sia La, and Bilafond La, on the glacier. Indian Army launched an operation to preempt the seizure of the passes by the Pakistan Army. Men of the Ladakh Scouts and Kumaon Regiment occupy Bilafond La on 13 April and Sia La on 17 April 1984 with the help of the Indian Air Force. Pakistan Army, in turn, learned of the presence of Ladakh Scouts on the passes during a helicopter recon mission. In response to these developments, Pakistan Army initiated an operation using troops from the Special Services Group and Northern Light Infantry to displace the three hundred or so Indian troops on the key passes. This operation led by the Pakistan Army led to the first armed clash on the glacier on 25 April 1984.[39]

June – July 1987: Operation Rajiv: Over the next three years, with Indian troops positioned at the critical passes, Pakistan Army attempted to seize heights overlooking the passes. One of the biggest successes achieved by Pakistan in this period was the seizure of a feature overlooking Bilafond La. This feature was named "Qaid Post" and for three years it dominated Indian positions on the glacier. Pakistani Army held Qaid post overlooked Bilafond La area and offered an excellent vantage point to view Indian Army activities. On 25 June 1987 Indian Army under the leadership of Brig. Gen. Chandan Nugyal, Major Varinder Singh, Lt. Rajiv Pande and Naib Subedar Bana Singh launched a successful strike on Qaid Post and captured it from Pakistani forces.[40] For his role in the assault, Subedar Bana Singh was awarded the Param Vir Chakra – India's highest gallantry award. The post was renamed Bana Post in his honour.[41]

September 1987: Operation Vajrashakti /Operation Qaidat: The Pakistan Army under Brig. Gen. Pervez Musharraf (later President of Pakistan) launched Operation Qaidat to retake Qaid peak. For this purpose units from Pakistan Army SSG (1st and 3rd battalions) assembled a major task force at the newly constructed Khaplu garrison.[42] Having detected Pakistani movements ahead of Operation Qaidat, the Indian Army initiated Op Vajrashakti to secure the now renamed Bana Post from Pakistani attack.[43][44]

Feb – May 1989: Operation Chumik/Operation Ibex : In February Indian troops launched an attack on Pakistani positions and in response Pakistan started operation Chumik successfully capturing Kamran top and destroying an Indian military base [45].In March 1989 Operation Ibex by the Indian Army attempted to seize the Pakistani post overlooking the Chumik Glacier. The operation was unsuccessful at dislodging Pakistani troops from their positions. Indian Army under Brig. R. K. Nanavatty launched an artillery attack on Kauser Base, the Pakistani logistical node in Chumik and successfully destroyed it. The destruction of Kauser Base induced Pakistani troops to vacate Chumik posts concluding Operation Ibex.[46]

28 July – 3 August 1992: Battle of Bahadur post: Indian Army launched Operation Trishul Shakti to protect the Bahadur post in Chulung when it was attacked by a large Pakistani assault team. On 1 August 1992, Pakistani helicopters were attacked by an Indian Igla missile and Brig. Masood Navid Anwari (PA 10117) then Force Commander Northern Areas and other accompanying troops were killed. This led to a loss of momentum on the Pakistani side and the assault stalled.[47]

May 1995: Battle of Tyakshi Post: Pakistan Army NLI units attacked Tyakshi post at the very southern edge of the Saltoro defense line. The attack was repulsed by Indian troops.[48]

June 1999: Indian Army under Brig. P. C. Katoch, Col. Konsam Himalaya Singh seized control of pt 5770 (Naveed Top/Cheema Top/Bilal Top) in the southern edge of the Saltoro defense line from Pakistan troops.[49]

Ground situation

In his memoirs, former Pakistani president General Pervez Musharraf states that Pakistan lost almost 986 square miles (2,550 km2) of territory that it claimed.[50] TIME states that the Indian advance captured nearly 1,000 square miles (2,600 km2) of territory claimed by Pakistan.[13]

Further attempts to reclaim positions were launched by Pakistan in 1990, 1995, 1996 and even in early 1999, just prior to the Lahore Summit.[citation needed]

The Indian army controls all of the 76 kilometres (47 mi) and 2553sq km area long Siachen Glacier and all of its tributary glaciers, as well as all the main passes and heights of the Saltoro Ridge[51] immediately west of the glacier, including Sia La, Bilafond La, and Gyong La—thus holding onto the tactical advantage of high ground.[52][53][54][55][56] Indians have been able to hold on to the tactical advantage of the high ground... Most of India's many outposts are west of the Siachen Glacier along the Saltoro Range. In an academic study with detailed maps and satellite images, co-authored by brigadiers from both the Pakistani and Indian military, pages 16 and 27: "Since 1984, the Indian army has been in physical possession of most of the heights on the Saltoro Range west of the Siachen Glacier, while the Pakistan army has held posts at lower elevations of western slopes of the spurs emanating from the Saltoro ridgeline. The Indian army has secured its position on the ridgeline."[This quote needs a citation]

The line between where Indian and Pakistani troops are presently holding onto their respective posts is being increasingly referred to as the Actual Ground Position Line (AGPL).[57][58]

Reception

Despite the high cost India maintains presence, as Pakistani control of Siachen would allow them to put radar and monitor all Indian airforce activity in Ladakh. It would also unite the Chinese and Pakistani front and allow them to launch a combined attack on India in case of a conflict. It saves Indian army from heavy cost of building defence infrastructure in the Nubra valley. While stakes are high for India, Pakistan cannot be threatened with Indian control of Siachen as the terrain does not allow India to launch an offensive on Pakistan but is a big question on Pakistan's ability to defend its territory claims. 1999 Kargil war was also an attempt to restrict supply route to Ladakh and Siachen.

Both sides have shown desire to vacate the glacier as there are environmental and cost concerns. There are numerous negotiations between both parties but have shown no significant progress, the process was further complicated when Pakistan violated ceasefire line in 1999 and built bunkers on Indian side and started artillery fire on Indian strategic highways resulting in 1999 Kargil War. Even if both sides agree to demilitarize a Pakistani occupation similar to 1999 will make it extremely difficult and expensive for India to reoccupy the glacier. The steady Chinese advancement in Himalayas is also a concern since 2020 Galwan Incident as the border understanding was violated and a similar incident, though unlikely is possible inflicting heavy cost on India.

Siachen is seen as a major military setback by the Pakistani Army.[59][60] Pakistani generals view the Siachen glacier as their land, which has been stolen by India.[61] When India occupied the Saltoro Ridge in April 1984, Benazir Bhutto publicly taunted the Pakistan Army as "fit only to fight its own citizens".[62] When, in June 1987, the Indian Army captured the 21,153 foot high "Quaid Post" and renamed it to "Bana Top", in honour of Naib Subedar Bana Singh, Bhutto once again publicly taunted the Pakistani generals, telling them to wear bangles if they cannot fight on the Siachen.[62][63][64]

American observers say that the military conflict between India and Pakistan over the Siachen Glacier "made no military or political sense".[61] An article in the Minneapolis Star Tribune stated: "Their combat over a barren, uninhabited world of questionable value is a forbidding symbol of their lingering, irreconcilability."[61] Stephen P. Cohen compared the conflict to "a struggle between two bald men over a comb. Siachen is a symbol of the worst aspects of their relationship."[61]

In the book Asymmetric Warfare in South Asia: The Causes and Consequences of the Kargil Conflict, Khan, Lavoy and Clary wrote:

The Pakistan army sees India's 1984 occupation of the Siachen Glacier as a major scar, outweighed only by Dhaka's fall in 1971. The event underscored the dilution of the Simla Agreement and became a domestic issue as political parties, led by Benazir Bhutto's Peoples Party, blamed an incompetent military government under Zia ul-Haq for failing to defend Pakistani-held territory — while Zia downplayed the significance of the loss.[65]

General Ved Prakash Malik, in his book Kargil from Surprise to Victory, wrote:

Siachen is considered a military setback by the Pakistan Army. That the Indians dominate the area from the Saltoro Ridge and Pakistani troops are nowhere near the Siachen Glacier is a fact never mentioned in public. The perceived humiliation at Siachen manifests itself in many ways. It is synonymous with Indian perfidy and a violation of the Shimla Agreement... In Pakistan, Siachen is a subject that hurts, just like a thorn in its flesh; it is also a psychological drain on the Pakistani Army. Pervez Musharraf had himself once commanded the Special Services Group (SSG) troops in this area and made several futile attempts to capture Indian posts.[59]

The cost of presence on glacier is heavy for both countries but it account for a larger portion of Pakistan's economy. India over the years has built permanent positions on ground.

Severe conditions

A cease-fire went into effect in 2003. Even before then, more soldiers were killed every year due to severe weather conditions than enemy fire. The two sides by 2003 had lost an estimated 2,000 personnel primarily due to frostbite, avalanches and other complications. Together, the nations have about 150 manned outposts along the glacier, with some 3,000 troops each. Official figures for maintaining these outposts are put at ~$300 and ~$200 million for India and Pakistan respectively. India built the world's highest helipad on the glacier at Point Sonam, 21,000 feet (6,400 m) above the sea level, to supply its troops. The problems of reinforcing or evacuating the high-altitude ridgeline have led to India's development of the Dhruv Mk III helicopter, powered by the Shakti engine, which was flight-tested to lift and land personnel and stores from the Sonam post, the highest permanently manned post in the world.[66] India also installed the world's highest telephone booth on the glacier.[67]

According to some estimates, 97% of the casualties in Siachen have been due to weather and altitude, rather than actual fighting.[68][page needed] In 2012, an avalanche hit Pakistan's Gayari military base, killing 129 soldiers and 11 civilians.[69][70]

Kargil War

One of the factors behind the Kargil War in 1999 when Pakistan sent infiltrators to occupy vacated Indian posts across the Line of Control was their belief that India would be forced to withdraw from Siachen in exchange of a Pakistani withdrawal from Kargil.[71] After the Kargil War, India decided to maintain its military outposts on the glacier, wary of further Pakistani incursions into Kashmir if they vacate from the Siachen Glacier posts.[72][page needed]

Visits

On 12 June 2005, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh became the first Indian Prime Minister to visit the area, calling for a peaceful resolution of the problem. In 2007, the President of India, Abdul Kalam became the first head of state to visit the area. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Siachen on 23 October 2014 to celebrate Diwali with the troops and boost their morale.[73]

The Chief of Staff of US Army, General George Casey on 17 October 2008 visited the Siachen Glacier along with Indian Army Chief, General Deepak Kapoor. US General visited for the purpose of "developing concepts and medical aspects of fighting in severe cold conditions and high altitude".[74][75]

Since September 2007, India has welcomed mountaineering and trekking expeditions to the forbidding glacial heights. The expeditions have been meant to show the international audience that Indian troops hold "almost all dominating heights" on the important Saltoro Ridge west of Siachen Glacier, and to show that Pakistani troops are nowhere near the 43.5-mile (70 km) Siachen Glacier and from 2019 the Indian Army And The Indian Government has allowed the tourists to visit the Siachen Glacier's Indian Army Post.[76]

In popular culture

- The Siachen glacier and its conflict was depicted in a 48-page comic book, Siachen: The Cold War, released in August 2012. Later its sequel, Battlefield Siachen, was released in January 2013.[77][78][79][80]

- The TV show Alpha Bravo Charlie had an extended multi-episode arc about one of the main characters being deployed to Siachen and losing his leg.[81][82]

List of post-ceasefire avalanches and landslides

2010–2011

On 11 February 2010, an avalanche struck an Indian army post in the Southern Glacier, killing one soldier. A base camp was also struck, that killed two Ladakh scouts. The same day, a single avalanche hit a Pakistani military camp in Bevan sector, killing 8 soldiers.[83]

In 2011, 24 Indian soldiers died on the Siachen glacier from the climate and accidents.[84] On 22 July, two Indian officers burned to death when a fire caught on their shelter.[85]

2012–2014

In the early morning of 7 April 2012, an avalanche hit a Pakistani military headquarters in the Gayari Sector, burying 129 soldiers of the 6th Northern Light Infantry battalion and 11 civilian contractors.[86][87] In the aftermath of the disaster, Pakistan's army chief General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani suggested India and Pakistan should withdraw all troops from the contested glacier.[88]

On 29 May, two Pakistani soldiers were killed in a landslide in the Chorbat Sector.[89]

On 12 December, an avalanche killed 6 Indian soldiers in the Sub Sector Hanif in Turtuk area, when troops of the 1st Assam regiment were moving between posts.[90][91] In 2012, a total of 12 Indian soldiers died of hostile weather conditions.[84]

In 2013, 10 Indian soldiers died due to weather conditions.[84]

2015

On 14 November 2015, an Indian captain from the Third Ladakh scouts died in an avalanche in the Southern Glacier while 15 others were rescued.[92]

2016

On 4 January 2016, four Indian soldiers of the Ladakh Scouts, were killed in an avalanche on the Southern Glacier while on patrol duty in Nobra Valley.[93]

On the morning of 3 February 2016, ten Indian soldiers including one Junior commissioned officer of the 6th Madras battalion were buried under the snow when a massive avalanche struck their post in the Northern Glacier at a height of 19,600 feet, on the Actual Ground Position Line.[94] Pakistani officials offered their help in search and rescue operations 30 hours after the incident, although it was declined by Indian military authorities.[95] During the rescue operations, the Indian army found Lance Naik Hanumanthappa alive, though in a critical condition, after being buried under 25 feet snow for 6 days. He was taken to Army Research and Referral Hospital in Delhi. His condition became critical later on due to multiple organ failure and lack of oxygen to brain and he died 11 February 2016.[96]

On 27 February, a civilian porter working with the Indian army in the Northern Glacier, fell to his death in a 130-foot crevasse.[97]

On 17 March, two Indian soldiers from the Chennai-21 regiment were killed, and bodies recovered in 12-feet deep ice.[98]

On 25 March, two Indian jawans died after they were buried in an avalanche in the Turtuk sector while on patrol.[99]

On 1 April, Indian General Dalbir Singh and General D. S. Hooda of the Northern Command visited the Siachen glacier in order to boost morale after 17 of its soldiers died in 2016.[100]

2018 – 2019

On 14 July 2018, 10 Indian Army soldiers were killed as result of Avalanche in Siachen.[101]

On 19 January 2019, 7 Indian Army soldiers were killed as result of an avalanche in Siachen.[102]

On 3 June 2019, Indian defense minister Rajnath Singh visited the Indian army's forward posts and base camp in Siachen. He interacted with the Indian soldiers deployed in Siachen and commended their courage. He claimed that more than 1,100 Indian soldiers have died defending the Siachen glacier.[9][8][103]

From 18 to 30 November 2019, 6 Indian soldiers and 2 Indian civilians porters were killed as result of an avalanche in the northern and southern part of Siachen glacier.[104][105]

References

Citations

- ^ Baruah, Amit. "India, Pak. ceasefire comes into being". The Hindu. 26 November 2003. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ P. Hoontrakul; C. Balding; R. Marwah, eds. (2014). The Global Rise of Asian Transformation: Trends and Developments in Economic Growth Dynamics (illustrated ed.). Springer. p. 37. ISBN 9781137412362. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

Siachen conflict (1984—2003)

Victorious: India / Defeated: Pakistan - ^ a b Desmond/Kashmir, Edward W. (31 July 1989). "The Himalayas War at the Top Of the World". Time. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

- ^ Kulkarni, Ramesh; Karpe, Anjali (26 October 2022). Siachen, 1987: Battle for the Frozen Frontier. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-93-5629-473-8.

- ^ a b c "War at the Top of the World". Time. 7 November 2005. Archived from the original on 12 April 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ "Army chief to visit Siachen this week". The Times of India. 8 January 2020. Archived from the original on 8 January 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ a b The Illustrated Weekly of India – Volume 110, Issues 14–26. Times of India.

Pakistani troops were forced out with over 200 casualties as against 36 Indian fatalities

- ^ a b "Defence Minister Rajnath Singh Bonds With Soldiers At Siachen Over Jalebi". NDTV. 4 June 2019. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ a b "Rajnath Singh visits Siachen to review security situation, pays tribute to martyrs – PICS". Times Now News. 3 June 2019. Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

Rajnath Singh also paid tribute to the martyred soldiers who sacrificed their lives while serving in Siachen. He went on to say, "More than 1,100 soldiers have made supreme sacrifice defending the Siachen glacier. The nation will always remain indebted to their service and sacrifice."

- ^ 846 Indian soldiers have died in Siachen since 1984 – Rediff.com News Archived 12 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Rediff.com. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ "Six dead after avalanche hits Army positions in Northern Siachen". The Times of India (TOI). 19 November 2019. Archived from the original on 20 November 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ "In Siachen 869 army men died battling the elements". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 19 February 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ a b Desmond, Edward W. (31 July 1989). "The Himalayas War at the Top Of the World". Time. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

- ^ Wirsing, Robert (15 November 1991). Pakistan's security under Zia, 1977–1988: the policy imperatives of a peripheral Asian state. Palgrave Macmillan, 1991. ISBN 9780312060671.

- ^ Child, Greg (1998). Thin air: encounters in the Himalayas. The Mountaineers Books, 1998. ISBN 9780898865882.[page needed]

- ^ Watson, Paul (26 November 2003). "India and Pakistan Agree to Cease-Fire in Kashmir". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 27 April 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Freddie (18 February 2021). "How a tiny line on a map led to conflict in the Himalaya". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ VAUSE, Mikel. Peering Over the Edge: The Philosophy of Mountaineering, p. 194.

- ^ CHILD, Greg. Mixed Emotions: Mountaineering Writings, p. 147.

- ^ a b c d P R Chari; Pervaiz Iqbal Cheema; Stephen P Cohen (2 September 2003). Perception, Politics and Security in South Asia: The Compound Crisis of 1990 (2003) (2003 ed.). Routledge (London); 1 edition (16 May 2003). p. 53. ISBN 978-0415307970. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ Modern world history- Chapter-The Indian subcontinent achieves independence/The Coldest War.

- ^ "UN Map showing CFL – UN document number S/1430/Add.2" (PDF). Dag Digital Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ U.N. Commission for India and Pakistan: annexes to the interim report (PDF). Dag Digital Library – the United Nations. p. 83. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ Treaty Series (PDF) (Volume 81 ed.). United Nations Treaty Collection. p. 274. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ "CFL marked on U.N. Map superimposed on satellite image". Pakistan Defence. 24 May 2015. Archived from the original on 29 May 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ^ a b c Facts vs bluff on Siachen, Kayani's suggestion worth pursuing Archived 22 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine, B.G. Verghese, Saturday, 21 April 2012, Chandigarh, India

- ^ Himalayan Journal Vol. 21

- ^ Himalayan Journal Vol. 25

- ^ Paul, Amit K. (13 July 2023). "The first GSI survey of the Siachen". The Hindu.

- ^ SANGAKU 71

- ^ "The Siachen Story: The Inadvertent Role of Two German Explorers in Starting the Race to the World's Highest Battlefield".

- ^ a b "Outside magazine article about Siachen battleground". Outsideonline.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ Dutta, Sujan (15 May 2006). "The Telegraph Calcutta : Nation". The Telegraph (India). Calcutta, India. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ Alpine Journal, 1984

- ^ "TPC G-7D". US Defense Mapping Agency. 1967. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ "Kumar's line vs Hodgson's line: The 'Lakshman rekha' that started an India-Pakistan fight". ThePrint. 31 December 2021.

- ^ "How India got Hodgson's Line erased and won the race to Siachen". 15 October 2022.

- ^ "The 'cartographic nightmare' of the Kashmir region, explained". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 18 February 2021.

- ^ "Siachen Glacier: Battling on the roof of the world". Indian Defence Review. Archived from the original on 21 June 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ Kunal Verma (2012). "XIV Op Rajiv". The Long Road to Siachen. Rupa. pp. 415–421. ISBN 978-81-291-2704-4.

- ^ Samir Bhattacharya (January 2014). Nothing But!. Partridge Publishing (Authorsolutions). pp. 146–. ISBN 978-1-4828-1732-4.

- ^ J. N. Dixit (2002). India-Pakistan in war & peace. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-30472-5.(pp. 39)

- ^ Baghel, Ravi; Nusser, Marcus (17 June 2015). "Securing the heights; The vertical dimension of the Siachen conflict between India and Pakistan in the Eastern Karakoram". Political Geography. 48. Elsevier: 31–32. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2015.05.001.

- ^ "the chumik operation".

- ^ The fight for Siachen Archived 2 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Brig. Javed Hassan (Retd) 22 April 2012, The Express Tribune

- ^ Harish Kapadia. Siachen Glacier: The Battle of Roses. Rupa Publications Pvt. Ltd. (India).

- ^ Siachen- Not a Cold War Archived 11 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Lt. Gen. P. N. Hoon (Retd)

- ^ Endgame at Siachen Archived 3 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Maj Gen Raj Mehta, AVSM, VSM (Retd) 2 December 2014, South Asia Defence and Strategic Review

- ^ Pervez Musharraf (2006). In the Line of Fire: A Memoir. Free Press. ISBN 0-7432-8344-9.(pp. 68–69)

- ^ Shukla, Ajai (28 August 2012). "846 Indian soldiers have died in Siachen since 1984". Business Standard India. Archived from the original on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ "Confrontation at Siachen, 26 June 1987". Bharat-rakshak.com. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

Detailed description of Indian forces taking control of Bilafond La in 1987

- ^ "War". Globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 5 September 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

Contrary to the oft-copied misstatement in the old error-plagued summary

- ^ NOORANI, A.G. (10 March 2006). "For the first time, the leaders of India and Pakistan seem close to finding a solution to the Kashmir problem". A working paper on Kashmir. Archived from the original on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ^ Bearak, Barry (23 May 1999). "THE COLDEST WAR; Frozen in Fury on the Roof of the World". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ Hakeem, Asad; Gurmeet Kanwal; Michael Vannoni; Gaurav Rajen (1 September 2007). "Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone" (PDF). Sandia Report. Sandia National Laboratories, Albuquerque, NM, USA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ^ Confirm ground position line on Siachen: BJP Archived 11 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine – 29 April 2006, The Hindu

- ^ Guns to fall silent on Indo-Pak borders Archived 27 May 2012 at archive.today 26 November 2003 – Daily Times

- ^ a b Malik 2006, p. 54.

- ^ Gokhale 2015, p. 148.

- ^ a b c d Dettman, Paul R. (2001). India Changes Course: Golden Jubilee to Millennium (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 109. ISBN 9780275973087. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ a b Malik 2006, p. 53.

- ^ Kapadia, Harish (2005). Into the Untravelled Himalaya: Travels, Treks, and Climbs. Indus Publishing. p. 235. ISBN 9788173871818. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ Lavoy 2009, p. 76.

- ^ Lavoy 2009, p. 75.

- ^ Shukla, Ajai (20 January 2013) [First published 7 March 2011]. "In Siachen, Dhruv proves a world-beater". Business Standard. New Delhi. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ^ "India Installs World's Highest Phone Booth Soldiers Fighting Along Kashmir Glacier Can Now Call Families, Army Says". Denver Rocky Mountain News. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2008.

- ^ Ives, Jack (5 August 2004). Himalayan Perceptions: Environmental Change and the Well-Being of Mountain Peoples. Routledge, 2004. ISBN 9781134369089.

- ^ "Pakistan declares Siachen avalanche buried dead". BBC. 29 May 2012. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Siachen: Pakistan declares buried troops dead after 52 days". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ Ganguly, Sumit; Kapur, S. Paul (2012). India, Pakistan, and the Bomb: Debating Nuclear Stability in South Asia (reprint ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 50. ISBN 9780231143752. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ Macdonald, Myra (2017). Defeat Is an Orphan: How Pakistan Lost the Great South Asian War. Random House India. ISBN 9789385990830.

After Kargil the Indian Army would resist any suggestion of a withdrawal from the world's highest battlefield for fear Pakistani troops would take over its vacated positions

- ^ Pundit, Rajat. "PM Modi visits Siachen, meets soldiers on Diwali". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ^ "US army chief's visit adds milestone to Indo-US ties". Daily News and Analysis. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ^ "Casey in Siachen on 'study tour'". dailytimes.co.pk. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ^ India opens Siachen to trekkers Times of India 13 September 2007

- ^ "Tribute to Siachen heroes Reviewd by Geetu Vaid". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ Vijetha S.N (11 September 2012). "Siachen war comes alive in a comic book". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "Valour of Siachen jawans now in a comic strip". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "An illustrated, literary salute to our warriors at Siachen glacier". Sunday-guardian.com. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "Alpha Bravo Charlie – Pakistani Television TV Show". Thepakistani.tv website. 19 March 2008. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ "Alpha Bravo Charlie — Pakistani TV Drama". Samaa TV News website. 3 October 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ "Siachen avalanche kills 3 Indian, 8 Pak soldiers". greaterkashmir.com. Archived from the original on 19 February 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ^ a b c News, National Turk (26 July 2014). "50 Indian soldiers die in Siachen in 3 yrs". nationalturk.com. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Indian army officers killed in Siachen fire". BBC News. 22 July 2011. Archived from the original on 19 February 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ^ "Pakistan resumes search for 135 buried by avalanche". BBC News. 8 April 2012. Archived from the original on 13 April 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- ^ "Huge search for trapped Pakistani soldiers". Al Jazeera. 7 April 2012. Archived from the original on 9 April 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- ^ "Pakistan army chief urges India on glacier withdrawal". BBC News. 18 April 2012. Archived from the original on 19 February 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ^ "Two soldiers killed in Siachen landsliding". geo.tv. Archived from the original on 19 February 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ AFP (16 December 2012). "Politics". livemint.com/. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ "Six Army soldiers killed in Siachen avalanche, one missing". NDTV.com. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ "Army Captain dies in avalanche in Siachen glacier, 15 soldiers rescued". CNN-IBN. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ "Siachen avalanche kills four Indian Army soldiers – Firstpost". Firstpost. 4 January 2016. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ "Siachen avalanche: Army declares all trapped soldiers dead; PM Modi pays condolences". The Indian Express. 4 February 2016. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ IANS, New Delhi/Islamabad. "Indian Army thanks Pakistan for offering help in Siachen rescue". KashmirDispatch. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ Peri, Dinakar (11 February 2016). "Siachen avalanche survivor Lance Naik Hanamanthappa passes away". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "Another tragedy at Siachen as army porter falls to death | Latest News & Updates at Daily News & Analysis". dna. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ "TN Army Village Loses Another Jawan in Siachen". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ "Siachen avalanche: Lance Havildar Bhawan Tamang killed, another soldier missing". The Indian Express. 25 March 2016. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ "Army Chief Visits Siachen Glacier After 17 Casualties in 3 Months Due to Avalanches". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ Hooda, Deepshikha (14 July 2018). "Siachen avalanche tragedy: Names of deceased soldiers released". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 8 February 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "2 More Bodies Found At Ladakh Avalanche Site, Number Of Dead Rise To 7". NDTV. 19 January 2019. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "'I salute,' tweets defence minister Rajnath Singh from Siachen Glacier". Hindustan Times. 3 June 2019. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ "Two soldiers killed as avalanche hits Army patrol in Siachen". The Times of India. 30 November 2019. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ "2 Army soldiers killed in avalanche in Siachen". India Today. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

Bibliography

- Lavoy, Peter R., ed. (2009). Asymmetric Warfare in South Asia: The Causes and Consequences of the Kargil Conflict. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139482820.

- Malik, V. P. (2006). Kargil from Surprise to Victory. HarperCollins Publishers India. ISBN 9788172236359.

- Gokhale, Nitin A (2015). Beyond NJ 9842: The SIACHEN Saga. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9789384052263.

Further reading

- Bearak, Barry (23 May 1999). "THE COLDEST WAR; Frozen in Fury on the Roof of the World". The New York Times.

- Siachen: Conflict Without End by V.R. Raghavan

- Myra MacDonald (2008) Heights of Madness: One Woman's Journey in Pursuit of a Secret War, Rupa, New Delhi ISBN 81-291-1292-2. The first full account of the Siachen war to be told from the Indian and Pakistani sides.

- Baghel, Ravi; Nusser, Marcus (17 June 2015). "Securing the heights; The vertical dimension of the Siachen conflict between India and Pakistan in the Eastern Karakoram". Political Geography. 48. Elsevier: 31–32. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2015.05.001.

- Wirsing, Robert (15 November 1991). Pakistan's security under Zia, 1977–1988: the policy imperatives of a peripheral Asian state. Palgrave Macmillan, 1991. ISBN 978-0-312-06067-1.

- Wilkinson, Freddie (18 February 2021). "How a tiny line on a map led to conflict in the Himalaya". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 18 February 2021. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

External links

- The Coldest War Archived 11 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Time report

- Siachen: The stalemate continues

- Siachen Glacier – Highest Battlefield Of The World

- "The vertical dimension of the Siachen conflict". Political Geography. 48: 24–36. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2015.05.001.