Sheikh Jarrah

Sheikh Jarrah (Arabic: الشيخ جراح, Hebrew: שייח׳ ג׳ראח) is a predominantly Palestinian neighborhood in East Jerusalem, two kilometres (1+1⁄4 miles) north of the Old City, on the road to Mount Scopus.[1][2] It received its name from the 13th-century tomb of Hussam al-Din al-Jarrahi, a physician of Saladin, located within its vicinity. The modern neighborhood was founded in 1865 and gradually became a residential center of Jerusalem's Muslim elite, particularly the al-Husayni family. After the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, it became under Jordanian-held East Jerusalem, bordering the no-man's land area with Israeli-held West Jerusalem until Israel occupied the neighborhood in the 1967 Six-Day War. Most of its present Palestinian population is said to come from refugees expelled from Jerusalem's Talbiya neighbourhood in 1948.[3]

Certain properties are subject to legal proceedings based on the application of two Israeli laws, the Absentee Property Law and the Legal and Administrative Matters Law of 1970. Israeli nationalists have been working to replace the Palestinian population in the area since 1967.[4] For five decades, several Israeli settlements have been built in and adjacent to Sheikh Jarrah.[5]

History

12th century

The Arab neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah was originally a village named after Hussam al-Din al-Jarrahi, who lived in the 12th century and was an emir and the personal physician to Saladin, the military leader whose army liberated[neutrality is disputed] Jerusalem from the Crusaders. Sheikh Hussam received the title jarrah(جراح<), meaning "healer" or "surgeon" in Arabic.[6][7]

Sheikh Jarrah established a zāwiya (literally "angle, corner", also meaning a small mosque or school), known as the Zawiya Jarrahiyya.[8] Sheikh Jarrah was buried on the grounds of the school. A tomb was built in 1201, which became a destination for worshippers and visitors. A two-story stone building incorporating a flour mill, Qasr el-Amawi, was built opposite the tomb in the 17th century.[9]

19th century

The neighborhood Sheikh Jarrah was established on the slopes of Mount Scopus, taking its name from the tomb of Sheikh Jarrah.[10] The initial residential construction works were commenced in 1865 by an important city notable, Rabah al-Husayni, who constructed a large manor among the olive groves near the Sheikh Jarrah tomb and outside the Damascus Gate. This action motivated many other Muslim notables from the Old City to migrate to the area and construct new homes,[11] including the Nashashibis, built homes in the upscale northern and eastern parts of the neighborhood. Sheikh Jarrah began to grow as a Muslim nucleus between the 1870s and 1890s.[9] Prayer at the Sheikh Jarrah tomb is said to bring good luck, particularly for those who raise chickens and eggs.[12] It became the first Arab Muslim-majority neighborhood in Jerusalem to be built outside the walls of the Old City. In the western part, houses were smaller and more scattered.[9]

Because it was founded by Rabah al-Husayni whose home formed the nucleus of Sheikh Jarrah, the neighborhood was locally referred to as the "Husayni Neighborhood."[11] It gradually became a center for the notable al-Husayni family whose members, including Jerusalem mayor Salim al-Husayni and the former treasurer of the Education Ministry in the Ottoman capital of Istanbul, Shukri al-Husayni, built their residences in the neighborhood.[11] Other notables who moved into the neighborhood included Faydi Efendi Shaykh Yunus, the Custodian of the Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock, and Rashid Efendi al-Nashashibi, a member of the District Administrative Council.[13] A mosque housing the Sheikh Jarrah tomb was built in 1895 on Nablus Road, north of the Old City and the American Colony.[12][14] In 1898 the Anglican St. George's School was built in Sheikh Jarrah and soon became the secondary educational institution where Jerusalem's elite sent their sons.[11]

Population around 1900

At the Ottoman census of 1905, the Sheikh Jarrah nahiya (sub-district) consisted of the Muslim quarters of Sheikh Jarrah, Hayy el-Husayni, Wadi el-Joz and Bab ez-Zahira, and the Jewish quarters of Shim'on Hatsadik and Nahalat Shim'on.[15] Its population was counted as 167 Muslim families (est. 1,250 people),[11] 97 Jewish families, and 6 Christian families.[15] It contained the largest concentration of Muslims outside the Old City.[15] Most of the Muslim population was born in Jerusalem, with 185 residents alone being members of the al-Husayni family.[11] A smaller number hailed from other parts of Palestine, namely Hebron, Jabal Nablus and Ramla, and from other parts of the Ottoman Empire, including Damascus, Beirut, Libya and Anatolia.[16] The Jewish population included Ashkenazim, Sephardim and Maghrebim while the Christians were mostly Protestants.[11] In 1918 the Sheikh Jarrah quarter of the Sheikh Jarrah nahiya contained about 30 houses.[9]

Jordanian and Israeli control

During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, 14 April, 78 Jews, mostly doctors and nurses, were killed on their way to Hadassah Hospital when their convoy was attacked by Arab forces as it passed through Sheikh Jarrah, the main road to Mount Scopus. In the wake of these hostilities, Mount Scopus was cut off from what would become West Jerusalem.[17] On 24 April the Haganah launched an attack on Sheikh Jarrah as part of Operation Yevusi but they were forced to retreat after action by the British Army.

From 1948, Sheikh Jarrah was on the edge of a UN-patrolled no-man's land between West Jerusalem and the Israeli enclave on Mount Scopus. A wall stretched from Sheikh Jarrah to Mandelbaum Gate, dividing the city.[18] Before 1948, Jews had purchased property in the West Bank and Jordan later passed the Custodian of Enemy Property Law and set a Custodian of Enemy Property to administer the property, amounting to some 30,000 dunums or about 5 percent of the total area of the West Bank.[19] In 1956, the Jordanian government moved 28 Palestinian families into Sheikh Jarrah who were displaced from their homes in Israeli-held Jerusalem during the 1948 War.[20] This was done in accordance with a deal reached between Jordan and UNRWA which stipulated that the refugee status of the families would be renounced in exchange for titles for ownership of the new houses after three years of residency, but the exchange did not take place.[21]

During the Six-Day War of 1967, Israel captured East Jerusalem, including Sheikh Jarrah. While discussing "The Legal and Administrative Matters Law of 1970" in the Knesset in 1968, The Minister of Justice stated that "if the Jordanian Custodian of Enemy Property in East Jerusalem sold a house to someone and received money, this house will not be returned", implying that the deal with UNRWA would be respected.[22]

Under international law, the area, effectively annexed by Israel, is a part of the occupied Palestinian territories.[23][24] Israel applies its laws there[23][24] and the legal proceedings in these and other similar cases in East Jerusalem, are based on the application of two Israeli laws, the Absentee Property Law and the Legal and Administrative Matters Law of 1970.[25]

Jewish groups have sought to gain property in Sheikh Jarrah claiming they were once owned by Jews, including the Shepherd Hotel compound, the Mufti's Vineyard, the building of the el-Ma'amuniya school, the Simeon the Just/Shimon HaTzadik compound, and the Nahlat Shimon neighborhood.

In May 2021, clashes occurred between Palestinians and Israeli police over further anticipated evictions in Sheikh Jarrah.[26][27]

Consulates and diplomatic missions

In the 1960s, many diplomatic missions and consulates opened in Sheikh Jarrah: The British Consulate at 19 Nashashibi Street,[28] the Turkish Consulate next door at 20 Nashashibi Street, the Belgian Consulate, the Swedish Consulate General at 5 Ibn Jubir Street, the Spanish Consulate, and the British Consulate General at 15 Nashashibi Street, and the United Nations mission at Saint George Street.[29]

Tony Blair, former envoy of the Diplomatic Quartet,[30] stays at the American Colony Hotel when visiting the region.[31]

Transportation

The neighbourhood's main street, Nablus Road, was previously part of route 60. In the 1990s a new dual carriageway with two lanes in each direction and a separate bus lane was built west of the neighborhood. Tracks were laid in the busway which since 2010 form the Red Line of the Jerusalem Light Rail.[32]

Landmarks

Shrines and tombs

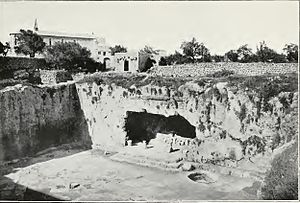

The Jewish presence in Sheikh Jarrah centered on the tomb of Shimon HaTzadik, one of the last members of the Great Assembly, the governing body of the Jewish people after the Babylonian Exile. According to the Babylonian Talmud, Shimon HaTzadik met with Alexander the Great when the Macedonian army passed through the Land of Israel and convinced him not to destroy the Second Temple. For years Jews made pilgrimages to his tomb in Sheikh Jarrah, a practice documented in travel literature. In 1876, the cave and the adjoining land, planted with 80 ancient olive trees, were purchased by the Jews for 15,000 francs. Dozens of Jewish families built homes on the property.[33] Other landmarks in Sheikh Jarrah are a medieval mosque dedicated to one of the soldiers of Saladin, St. George's Anglican Cathedral and the Tomb of the Kings.

St. John of Jerusalem Eye Hospital

The St John of Jerusalem Eye Hospital is an institution of The Order of St John that provides eye care in the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem. Patients receive care regardless of race, religion or ability to pay.[34] The hospital first opened in 1882 on Hebron Road opposite Mount Zion.[35] The building in Sheikh Jarrah opened in 1960 on Nashashibi Street.

St. Joseph's French Hospital

The St. Joseph's French Hospital is situated across the street from St John of Jerusalem Eye Hospital and is run by a French Catholic charity. It is a 73-bed hospital with three main operating theaters, coronary care unit, X-ray, laboratory facilities, and outpatient clinic. Facilities in internal medicine, surgery, neurosurgery, E.N.T., pediatric surgery and orthopedics.[36]

Shepherd Hotel

The Shepherd Hotel in Sheikh Jarrah was a villa built for the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseini, who never lived there and transferred property rights to his personal secretary, George Antonius and his wife, Katy Antonius.[37] After the death of George Antonius in 1942, his widow invited many of Jerusalem's elite to her house, though only one Jew. While living in the house, Katy Antonius had a highly publicized affair with the commander of the British forces in Palestine, Evelyn Barker. In 1947, the Jewish underground Irgun blew up a house nearby. Antonius left the house, and a regiment of Scottish Highlanders was stationed there.[37] After the 1948 war, it was taken over by the Jordanian authorities and turned into a pilgrim hotel. In 1985, it was bought by the American Jewish millionaire Irving Moskowitz and continued to operate as a hotel, renamed the Shefer Hotel. The Israeli border police used it as base for several years.[37] In 2007, when Moskowitz initiated plans to build 122 apartments on the site of the hotel, the work was condemned by the British government.[38] In 2009 the plan was modified, but was still condemned by the U.S. and UK governments,[39] Permission to build 20 apartments near the hotel was given in 2009, and formal approval was announced by the Jerusalem municipality on March 23, 2010, hours before Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu met with President Barack Obama.[40] Haaretz reported that, "an existing structure in the area will be torn down to make room for the housing units, while the historic Shepherd Hotel will remain intact. A three-story parking structure and an access road will also be constructed on site."[41] The hotel was finally demolished on January 9, 2011.[42]

Cultural references

Sheikh Jarrah is the subject of a 2012 documentary film, My Neighbourhood, co-directed by Julia Bacha and Rebekah Wingert-Jabi and co-produced by Just Vision and Al Jazeerah.

Notable people

- George Antonius

- Kai Bird

- Mohammed El-Kurd, journalist, poet and activist for Palestinian rights

- Yonatan Yosef, Israeli rabbi

Gallery

-

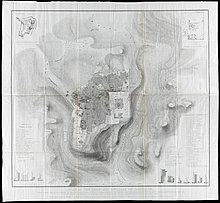

Aerial view of Shepherd Hotel, 1933

-

Sheikh Jarrah in 1945 in the Survey of Palestine

-

Sheikh Jarrah briefly held by the Harel Brigade (Palmach) 24 April 1948

-

Sheikh Jarrah after Operation Yevusi

-

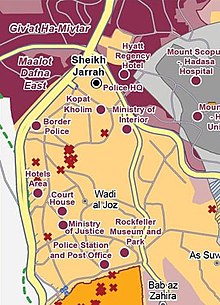

OCHAoPT map of Palestinian communities under threat of eviction in East Jerusalem, 2016

References

- ^ Zirulnick, Ariel. Bryant, Christa Case. Five controversial Jewish neighborhoods in East Jerusalem Archived 2021-02-12 at the Wayback Machine Christian Science Monitor. 10 January 2011

- ^ Medding, Shira. Khadder, Kareem. Jerusalem committee OKs controversial construction plan Archived 2011-02-22 at the Wayback Machine CNN 07 February 2011

- ^ Neri Livneh, 'So What's It Like Being Called an Israel-hater?,' Archived 2017-03-15 at the Wayback Machine Haaretz, 16 March 2010.

- ^ Israel under pressure to rein in settlers after clashes at al-Aqsa mosque: Fresh skirmishes break out in the early hours of Sunday amid protests by Palestinians against evictions in East Jerusalem Archived 2021-05-09 at the Wayback Machine, Financial Times, 9 May 2021: "Jewish settlers have for decades targeted Sheikh Jarrah, a middle-class Arab neighbourhood between east and west Jerusalem, aiming to turn it into a majority Jewish area."

- ^ Scott A. Bollens (6 January 2000). On Narrow Ground: Urban Policy and Ethnic Conflict in Jerusalem and Belfast. SUNY Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-7914-4413-9. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

These colonies — Ramot Eshkol, Givat Hamivtar, Maalot Dafna, and French Hill — were built in and adjacent to the Arab Sheikh Jarrah quarter.

- ^ The Sheikh Jarrah Affair: The Strategic Implications of Jewish Settlement in an Arab Neighborhood in East Jerusalem Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, JIIS Studies Series no. 404, 2010. Yitzhak Reiter and Lior Lehrs, The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies. On [1] Archived 2016-03-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Marim Shahin (2005). Palestine: A Guide. Interlink Books. pp. 328–329. ISBN 1-56656-557-X.

- ^ Hawari, M. (2007). Ayyubid Jerusalem (1187-1250): an architectural and archaeological study (Illustrated ed.). Archaeopress. ISBN 9781407300429. Archived from the original on 2021-05-08. Retrieved 2016-04-18.

- ^ a b c d Kark, Ruth; Landman, Shimon (July 1980). "The Establishment of Muslim Neighbourhoods in Jerusalem, Outside the Old City, During the Late Ottoman Period". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 112 (2): 113–115. doi:10.1179/peq.1980.112.2.113.

- ^ Oesterreicher, J. M.; Sinai, Anne (1974). Jerusalem (Illustrated ed.). John Day. p. 22. ISBN 9780381982669. Archived from the original on 2021-05-11. Retrieved 2016-04-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bussow, 2011, pp. 160 Archived 2021-05-11 at the Wayback Machine- 161 Archived 2021-05-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Winter, Dave (1999). Israel handbook: with the Palestinian Authority areas (2nd, illustrated ed.). Footprint Travel Guides. p. 189. ISBN 9781900949484. Archived from the original on 2021-05-11. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ^ Bussow, 2011, p. 163 Archived 2021-05-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ma'oz, Moshe; Nusseibeh, Sari (2000). Jerusalem: Points of Friction, and Beyond (Illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 143. ISBN 9789041188434. Archived from the original on 2021-05-11. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ^ a b c Adar Arnon, The quarters of Jerusalem in the Ottoman period, Middle Eastern Studies, vol. 28, 1992, pp 1–65.

- ^ Bussow, 2011, p. 162 Archived 2021-05-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Shragai, N. (2009-07-27). "The Sheikh Jarrah-Shimon HaTzadik Neighborhood". Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 2011-06-08. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- ^ "Kai Bird's 'Gate': One Foot In Israel, One In Palestine". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 2018-05-10. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- ^ Shehadeh, Raja (1997). "Land and Occupation: A Legal Review". Palestine-Israel Journal.

- ^ Izenberg, Dan (29 September 2010). "Sheikh Jarrah Palestinians fear new evictions". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ "What is happening in occupied East Jerusalem's Sheikh Jarrah?". Al Jazeera English. 1 May 2020. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ "The Systematic dispossession of Palestinian neighborhoods in Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan" (PDF). Peace Now. 6 June 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Stop evictions in East Jerusalem neighbourhood immediately, UN rights office urges Israel". UN News. 7 May 2021. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021.

- ^ a b Alsaafin, Linah (1 May 2021). "What is happening in occupied East Jerusalem's Sheikh Jarrah?". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021.

- ^ "OHCHR | Press briefing notes on Occupied Palestinian Territory".

- ^ Kingsley, Patrick (7 May 2021). "Evictions in Jerusalem Become Focus of Israeli-Palestinian Conflict". New York Times. Jerusalem. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Rubin, Shira (9 May 2021). "How a Jerusalem neighborhood reignited the Israeli-Palestinian conflict". Washington Post. Jerusalem. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ United Kingdom – Consulate General in Jerusalem – Our offices in Jerusalem, archived from the original on 2011-02-11, retrieved 2011-01-23

- ^ List of embassies and consulates in Israel, archived from the original on 2009-11-30, retrieved 2009-11-07

- ^ Josh May (2015-05-27). "Tony Blair resigns as Middle East peace envoy". Politics Home. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- ^ "The Englishwoman who ran an oasis in the heart of the conflict – Haaretz – Israel News".

- ^ "The Jerusalem Light Rail Map", Citypass, archived from the original on 2010-06-13, retrieved 2009-11-08

- ^ "Jerusalem Issue Briefs-The U.S.-Israeli Dispute over Building in Jerusalem: The Sheikh Jarrah-Shimon HaTzadik Neighborhood". 9 June 2010. Archived from the original on 9 June 2010.

- ^ "St John Eye Hospital – Improving Sight, Changing Lives". Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- ^ Kroyanker, D. (November 1, 2003), "Jerusalem Architecture [Hardcover]", Vendome Press (Revised ed.), ISBN 978-0-86565-147-0[page needed]

- ^ "St. Joseph's French Hospital – BioJerusalem". Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ^ a b c "File of old letters and photos shows Shepherd Hotel is no stranger to scandal".

- ^ Britain protests to Olmert about illegal settlement Archived 2011-04-02 at the Wayback Machine Donald Macintyre, The Independent, May 5, 2007

- ^ Israel's evictions upset even its friends Archived 2017-01-07 at the Wayback Machine, Ian Black, The Guardian, August 4, 2009

- ^ New East Jerusalem homes approved hours before Netanyahu-Obama meet Archived 2010-03-26 at the Wayback Machine, Nir Hasson, Haaretz, March 23, 2010.

- ^ Israel to U.S.: Latest East Jerusalem building okayed last year Archived 2010-03-26 at the Wayback Machine, Nir Hasson, Barak Ravid and Natasha Mozgovaya, Haaretz Correspondents, and News Agencies, Haaretz, March 24, 2010

- ^ Matthew Lee (Jan 9, 2010). "Clinton slams Israeli demolition of historic hotel". Associated Press. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

Bibliography

- Bussow, Johann (2011). Hamidian Palestine: Politics and Society in the District of Jerusalem 1872-1908. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004205697. Archived from the original on 2021-04-18. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- Yitzhak Reiter, Lior Lehrs (2010). The Sheikh Jarrah Affair: The Strategic Implications of Jewish Settlement in an Arab Neighborhood in East Jerusalem Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, JIIS Studies Series no. 404. The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies; On [2] Archived 2016-03-13 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

Media related to Sheikh Jarrah at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sheikh Jarrah at Wikimedia Commons