Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes

This article is missing information about Scheduled Tribes. (November 2023) |

The Scheduled Castes[1] and Scheduled Tribes are officially designated groups of people and among the most disadvantaged socio-economic groups in India.[2] The terms are recognized in the Constitution of India and the groups are designated in one or other of the categories.[3]: 3 For much of the period of British rule in the Indian subcontinent, they were known as the Depressed Classes.[3]: 2

In modern literature, many castes under the Scheduled Castes category are sometimes referred to as Dalit, meaning "broken" or "dispersed" for the untouchables.[5][6] The term having been popularised by the Dalit leader B. R. Ambedkar during the independence struggle.[5] Ambedkar preferred the term Dalit over Gandhi's term Harijan, meaning "people of Hari" (lit. 'Man of God').[5] Similarly, the Scheduled Tribes are often referred to as Adivasi (earliest inhabitants), Vanvasi (inhabitants of forest) and Vanyajati (people of forest). However, the Government of India refrains from using such derogatory and incorrect terms that carry controversial connotations. For example, 'Dalit', which literally means 'oppressed', has been historically associated with notions of uncleanness, carries implications of reinforcing the concept of untouchability. Similarly, 'Adivasi', which means 'original inhabitants', carries implications of native and immigrant distinctions and also perpetuates the stereotypes of being civilized and uncivilized.[7] Therefore, the Constitutionally recognized inclusive terms "Scheduled Castes" (Anusuchit Jati) and "Scheduled Tribes" (Anusuchit Janjati) are preferred in official usage, as these designated terms are intended to address socio-economic disabilities, rather than to reimpose those social stigmas and issues.[8][9] In September 2018, the government "issued an advisory to all private satellite channels asking them to refrain from using the derogatory nomenclature 'Dalit', though rights groups and intellectuals have come out against any shift from 'Dalit' in popular usage".[10]

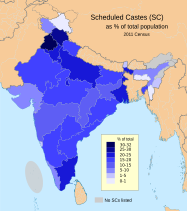

The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes comprise about 16.6% and 8.6%, respectively, of India's population (according to the 2011 census).[11][12] The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950 lists 1,108 castes across 28 states in its First Schedule,[13] and the Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order, 1950 lists 744 tribes across 22 states in its First Schedule.[14]

Since the independence of India, the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes were given Reservation status, guaranteeing political representation, preference in promotion, quota in universities, free and stipended education, scholarships, banking services, various government schemes and the Constitution lays down the general principles of positive discrimination for SCs and STs.[15][16]: 35, 137

Definition

[edit]- Scheduled Castes

Article 366 (24) of the Constitution of India defines the Scheduled Castes as:[17]

Such castes, races or tribes or part of or groups within such castes, races or tribes as are deemed under Article 341 to be Scheduled Castes for the purpose of this [Indian] constitution.

- Scheduled Tribes

Article 366 (25) of the Constitution of India defines the Scheduled Tribes as:[18][17]

Such tribes or tribal communities or part of or groups within such tribes or tribal communities as are deemed under Article 342 to the Scheduled Tribes for the purposes of this [Indian] Constitution.

Identification and procedures

[edit]Article 341

(1) The President may with respect to any State or Union Territory and where it is a State after consultation with the Governor thereof, by public notification specify the castes, races or tribes or parts of or groups within castes, races or tribes which shall for the purposes of this Constitution be deemed to be Scheduled Castes in relation to that State or Union Territory, as the case may be.

(2) Parliament may by law include in or exclude from the list of Scheduled Castes specified in a notification issued under clause of any caste, race or tribe or part of or group within any caste, race or tribe, but save as aforesaid a notification issued under the said clause shall not be varied by any subsequent notification.[17]

Article 342

(1) The President may with respect to any State or Union Territory and where it is a State, after consultation with the Governor thereof by public notification, specify the tribes or tribal communities or parts of or groups within tribes or tribal communities which shall for the purpose of this Constitution be deemed to be Scheduled Tribes in relation to that State or Union Territory, as the case may be.

(2) Parliament may by law include in or exclude from the list of Scheduled Tribes specified in a notification issued under clause any tribe or tribal community or part of or group within any tribe or tribal community, but save as aforesaid a notification issued under the said clause shall not be varied by any subsequent notification.[17]

In a broader sense, the term 'Scheduled' refers to the legal list of specific castes and tribes of the states and union territories, as enacted in the Constitution of India, with the purpose of social justice by ensuring social security, and providing adequate representation in education, employment, and governance to promote their upliftment and integration into mainstream society.[19][20][21] The process of including and excluding communities, castes, or tribes to/from the list of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes adheres to certain silent criteria and procedures established by the Lokur committee in 1965.[22][23] For Scheduled Castes (SCs), the criteria involve extreme social, educational, and economic backwardness resulting from the practice of untouchability.[24] On the other hand, Scheduled Tribes (STs) are identified based on indications of primitive traits, distinctive culture, geographical isolation, shyness of contact with the larger community, and overall backwardness.[24] The scheduling process refers back to the definitions of communities used in the colonial census along with modern anthropological study and is guided by Article 341 and 342. Per the first clause of Article 341 and 342, the list of Scheduled communities is subject to specific state and union territory, with area restrictions to districts, subdistricts, and tehsils.[25][26][27][28] Furthermore, members of Scheduled Communities are entitled based on religious criteria: Scheduled Castes must be adherents of Hinduism, Sikhism, or Buddhism,[29] whereas Scheduled Tribes can belong to any religion to be recognized as Scheduled.[30][19]

History

[edit]Pre-independence

[edit]The evolution of the lower caste and tribe into the modern-day Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe is complex. The caste system as a stratification of classes in India originated about 2,000 years ago, and has been influenced by dynasties and ruling elites, including the Mughal Empire and the British Raj.[31][32] The Hindu concept of Varna historically incorporated occupation-based communities.[31] Some low-caste groups, such as those formerly called untouchables[33] who constitute modern-day Scheduled Castes, were considered outside the Varna system.[34][35]

Since the 1850s, these communities were loosely referred to as Depressed Classes, with the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. The early 20th century saw a flurry of activity in the British authorities assessing the feasibility of responsible self-government for India. The Morley–Minto Reforms Report, Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms Report and the Simon Commission were several initiatives in this context. A highly contested issue in the proposed reforms was the reservation of seats for representation of the Depressed Classes in provincial and central legislatures.[36]

In 1935, the UK Parliament passed the Government of India Act 1935, designed to give Indian provinces greater self-rule and set up a national federal structure. The reservation of seats for the Depressed Classes was incorporated into the act, which came into force in 1937. The Act introduced the term "Scheduled Castes", defining the group as "such castes, parts of groups within castes, which appear to His Majesty in Council to correspond to the classes of persons formerly known as the 'Depressed Classes', as His Majesty in Council may prefer".[3] This discretionary definition was clarified in The Government of India (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1936, which contained a list (or Schedule) of castes throughout the British-administered provinces.[3]

Post-independence

[edit]After independence the Constituent Assembly continued the prevailing definition of Scheduled Castes and Tribes, giving (via articles 341 and 342) the president of India and governors of the states a mandate to compile a full listing of castes and tribes (with the power to edit it later, as required). The first list of castes and tribes was created through two orders: The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950, and The Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order, 1950, containing 821 castes and 296 tribes (overlapping nature), respectively, derived from colonial lists.[a] Subsequently, the Presidential Scheduled List was modified in 1956 by the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Lists (Modification) Order, 1956, to include other areas, newly formed states/UTs, and communities that had not been considered during the adoption of the Constitution of India.[39] and The Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order, 1950,[40] However, the classification and maintenance of the list Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes was initially intended to be a state matter during drafting of the constitution, concerns over political misuse led to the centralization of authority under the Presidential Scheduled Lists. After 15 years since the order of listing Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, the government adopted updated criteria for inclusion and exclusion based on the Lokur committee report of 1965.[23] Due to inclusive policies, many communities were added to the Presidential Scheduled List through amendments since the adoption of the Constitution, bringing the total to over 1,000 Scheduled Castes and over 500 Scheduled Tribes by 2018.[41]

Demographics

[edit]Population

[edit]| State and Union Territories | Total population of the State and Union Territories |

Scheduled Castes | Scheduled Tribes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of notified communities[44] (as of October 2017) |

Total population | % of Total Scheduled Castes |

% of State and UT population |

No. of notified communities[44] (as of December 2017) |

Total population | % of Total Scheduled Tribes |

% of State and UT population | ||

| Andhra Pradesh (incl. Telangana) | 84,580,777 | AP: 61 TG: 59 |

13,878,078 | 6.89 | 16.41 | AP: 34 TG: 32 |

5,918,073 | 5.66 | 7 |

| Arunachal Pradesh | 1,383,727 | 0 | — | — | — | 16 | 951,821 | 0.91 | 68.79 |

| Assam | 31,205,576 | 16 | 2,231,321 | 1.11 | 7.15 | 29 | 3,884,371 | 3.72 | 12.45 |

| Bihar | 104,099,452 | 23 | 16,567,325 | 8.23 | 15.91 | 32 | 1,336,573 | 1.28 | 1.28 |

| Chhattisgarh | 25,545,198 | 44 | 3,274,269 | 1.63 | 12.82 | 42 | 7,822,902 | 7.48 | 30.62 |

| Goa | 1,458,545 | 5 | 25,449 | 0.01 | 1.74 | 8 | 149,275 | 0.14 | 10.23 |

| Gujarat | 60,439,692 | 36 | 4,074,447 | 2.02 | 6.74 | 32 | 8,917,174 | 8.53 | 14.75 |

| Haryana | 25,351,462 | 37 | 5,113,615 | 2.54 | 20.17 | 0 | — | — | — |

| Himachal Pradesh | 6,864,602 | 57 | 1,729,252 | 0.86 | 25.19 | 10 | 392,126 | 0.38 | 5.71 |

| Jharkhand | 32,988,134 | 22 | 3,985,644 | 1.98 | 12.08 | 32 | 8,645,042 | 8.27 | 26.21 |

| Karnataka | 61,095,297 | 101 | 10,474,992 | 5.2 | 17.15 | 50 | 4,248,987 | 4.06 | 6.95 |

| Kerala | 33,406,061 | 69 | 3,039,573 | 1.51 | 9.1 | 43 | 484,839 | 0.46 | 1.45 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 72,626,809 | 48 | 11,342,320 | 5.63 | 15.62 | 46 | 15,316,784 | 14.65 | 21.09 |

| Maharashtra | 112,374,333 | 59 | 13,275,898 | 6.59 | 11.81 | 47 | 10,510,213 | 10.05 | 9.35 |

| Manipur | 2,855,794 | 7 | 97,328 | 0.05 | 3.41 | 34 | 1,167,422 | 1.12 | 40.88 |

| Meghalaya | 2,966,889 | 16 | 17,355 | 0.01 | 0.58 | 17 | 2,555,861 | 2.44 | 86.15 |

| Mizoram | 1,097,206 | 16 | 1,218 | 0 | 0.11 | 15 | 1,036,115 | 0.99 | 94.43 |

| Nagaland | 1,978,502 | 0 | — | — | — | 5 | 1,710,973 | 1.64 | 86.48 |

| Odisha | 41,974,218 | 95 | 7,188,463 | 3.57 | 17.13 | 62 | 9,590,756 | 9.17 | 22.85 |

| Punjab | 27,743,338 | 39 | 8,860,179 | 4.4 | 31.94 | 0 | — | — | — |

| Rajasthan | 68,548,437 | 59 | 12,221,593 | 6.07 | 17.83 | 12 | 9,238,534 | 8.84 | 13.48 |

| Sikkim | 610,577 | 4 | 28,275 | 0.01 | 4.63 | 4 | 206,360 | 0.2 | 33.8 |

| Tamil Nadu | 72,147,030 | 76 | 14,438,445 | 7.17 | 20.01 | 36 | 794,697 | 0.76 | 1.1 |

| Tripura | 3,673,917 | 34 | 654,918 | 0.33 | 17.83 | 19 | 1,166,813 | 1.12 | 31.76 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 199,812,341 | 66 | 41,357,608 | 20.54 | 20.7 | 15 | 1,134,273 | 1.08 | 0.57 |

| Uttarakhand | 10,086,292 | 65 | 1,892,516 | 0.94 | 18.76 | 5 | 291,903 | 0.28 | 2.89 |

| West Bengal | 91,276,115 | 60 | 21,463,270 | 10.66 | 23.51 | 40 | 5,296,953 | 5.07 | 5.8 |

| Andaman and Nicobar Islands | 380,581 | 0 | — | — | — | 6 | 28,530 | 0.03 | 7.5 |

| Chandigarh | 1,055,450 | 36 | 199,086 | 0.1 | 18.86 | 0 | — | — | — |

| Dadra and Nagar Haveli | 343,709 | 4 | 6,186 | 0 | 1.8 | 7 | 178,564 | 0.17 | 51.95 |

| Daman and Diu | 243,247 | 5 | 6,124 | 0 | 2.52 | 5 | 15,363 | 0.01 | 6.32 |

| Jammu and Kashmir | 12,541,302 | 13 | 924,991 | 0.46 | 7.38 | 12 | 1,493,299 | 1.43 | 11.91 |

| Lakshadweep | 64,473 | 0 | — | — | — | native pop. | 61,120 | 0.06 | 94.8 |

| Delhi | 16,787,941 | 36 | 2,812,309 | 1.4 | 16.75 | 0 | — | — | — |

| Puducherry | 1,247,953 | 16 | 196,325 | 0.1 | 15.73 | 0 | — | — | — |

| India | 1,210,854,977 | 1,284* | 201,378,372 | 100 | 16.63 | 747* | 104,545,716 | 100 | 8.63 |

- The census figures for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes represent selective demography, as the first clause of Articles 341 and 342 specifies that Schedule status is specific to state or union territory (indicating nativeness of the region and the socio-economic disabilities arising therein), not to the whole country. For example, during the census operation, if a member of a notified community is not present in the state or union territory where the community is recognized as such, or if a member of Scheduled Castes follows religions other than Hinduism, Buddhism, or Sikhism, they are not counted as part of the Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes, but rather as part of the general population.[45][46][47]

- In the states of Arunachal Pradesh and Nagaland, and the Union Territories of Andaman and Nicobar Islands and Lakshadweep, no community is notified as Scheduled Castes; thus, there is no Scheduled Caste population.[48]

- In the states of Punjab and Haryana, and the Union Territories of Delhi, Chandigarh and Puducherry, no community is notified as Scheduled Tribes; thus, there is no Scheduled Tribe population.[48]

Religion

[edit]| States and Union Territories | Scheduled Caste | Scheduled Tribe | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hindu | Sikh | Buddhist | Hindu | Muslim | Christian | Sikh | Buddhist | Jain | Others | Religion not stated | |

| Andhra Pradesh (incl. Telangana) | 13,848,473 | 2,053 | 27,552 | 5,808,126 | 28,586 | 57,280 | 890 | 608 | 644 | 810 | 21,129 |

| Arunachal Pradesh | — | — | — | 97,629 | 3,567 | 389,507 | 245 | 96,391 | 441 | 358,663 | 5,378 |

| Assam | 2,229,445 | 1,335 | 541 | 3,349,772 | 13,188 | 495,379 | 387 | 7,667 | 424 | 12,039 | 5,515 |

| Bihar | 16,563,145 | 1,595 | 2,585 | 1,277,870 | 11,265 | 32,523 | 150 | 252 | 123 | 10,865 | 3,525 |

| Chhattisgarh | 3,208,726 | 1,577 | 63,966 | 6,933,333 | 8,508 | 385,041 | 620 | 1,078 | 312 | 488,097 | 5,913 |

| Goa | 25,265 | 7 | 177 | 99,789 | 531 | 48,783 | 20 | 62 | 18 | 12 | 60 |

| Gujarat | 4,062,061 | 1,038 | 11,348 | 8,747,349 | 34,619 | 120,777 | 1,262 | 1,000 | 1,266 | 3,412 | 7,489 |

| Haryana | 4,906,560 | 204,805 | 2,250 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Himachal Pradesh | 1,709,634 | 15,939 | 3,679 | 307,914 | 37,208 | 275 | 294 | 45,998 | 54 | 23 | 360 |

| Jharkhand | 3,983,629 | 669 | 1,346 | 3,245,856 | 18,107 | 1,338,175 | 984 | 2,946 | 381 | 4,012,622 | 25,971 |

| Karnataka | 10,418,989 | 2,100 | 53,903 | 4,171,265 | 44,599 | 12,811 | 802 | 472 | 1,152 | 665 | 17,221 |

| Kerala | 3,039,057 | 291 | 225 | 431,155 | 18,320 | 32,844 | 42 | 44 | 18 | 376 | 2,040 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 11,140,007 | 2,887 | 199,426 | 14,589,855 | 33,305 | 88,548 | 1,443 | 1,796 | 852 | 584,338 | 16,647 |

| Maharashtra | 8,060,130 | 11,484 | 5,204,284 | 10,218,315 | 112,753 | 20,335 | 2,145 | 20,798 | 1,936 | 93,646 | 40,285 |

| Manipur | 97,238 | 39 | 51 | 8,784 | 4,296 | 1,137,318 | 209 | 2,326 | 288 | 11,174 | 3,027 |

| Meghalaya | 16,718 | 528 | 109 | 122,141 | 10,012 | 2,157,887 | 301 | 6,886 | 254 | 251,612 | 6,768 |

| Mizoram | 1,102 | 9 | 107 | 5,920 | 4,209 | 933,302 | 62 | 91,054 | 343 | 751 | 474 |

| Nagaland | — | — | — | 15,035 | 5,462 | 1,680,424 | 175 | 4,901 | 500 | 3,096 | 1,380 |

| Odisha | 7,186,698 | 825 | 940 | 8,271,054 | 15,335 | 816,981 | 1,019 | 1,959 | 448 | 470,267 | 13,693 |

| Punjab | 3,442,305 | 5,390,484 | 27,390 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Rajasthan | 11,999,984 | 214,837 | 6,772 | 9,190,789 | 13,340 | 25,375 | 663 | 445 | 622 | 1,376 | 5,924 |

| Sikkim | 28,016 | 15 | 244 | 40,340 | 369 | 16,899 | 72 | 1,36,041 | 125 | 12,306 | 208 |

| Tamil Nadu | 14,435,679 | 1,681 | 1,085 | 783,942 | 2,284 | 7,222 | 84 | 50 | 45 | 55 | 1,015 |

| Tripura | 654,745 | 69 | 104 | 888,790 | 2,223 | 153,061 | 250 | 1,19,894 | 318 | 768 | 1,509 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 41,192,566 | 27,775 | 137,267 | 1,099,924 | 21,735 | 1,011 | 264 | 353 | 410 | 2,404 | 8,172 |

| Uttarakhand | 1,883,611 | 7,989 | 916 | 287,809 | 1,847 | 437 | 364 | 1,142 | 7 | 9 | 288 |

| West Bengal | 21,454,358 | 3,705 | 5,207 | 3,914,473 | 30,407 | 343,893 | 1,003 | 220,963 | 876 | 774,450 | 10,888 |

| Andaman and Nicobar Islands | — | — | — | 156 | 1,026 | 26,512 | 0 | 85 | 0 | 344 | 407 |

| Chandigarh | 176,283 | 22,659 | 144 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Dadra and Nagar Haveli | 6,047 | 0 | 139 | 175,305 | 242 | 2,658 | 15 | 12 | 4 | 54 | 274 |

| Daman and Diu | 6082 | 1 | 41 | 15,207 | 125 | 16 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 13 |

| Jammu and Kashmir | 913,507 | 11,301 | 183 | 67,384 | 1,320,408 | 1,775 | 665 | 100,803 | 137 | 1,170 | 957 |

| Lakshadweep | — | — | — | 44 | 61,037 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 10 | 4 | 16 |

| Delhi | 2,780,811 | 25,934 | 5,564 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Puducherry | 196,261 | 33 | 31 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| India (%) |

189,667,132 (94.18%) |

5,953,664 (2.96%) |

5,757,576 (2.86%) |

84,165,325 (80.51%) |

1,858,913 (1.78%) |

10,327,052 (9.88%) |

14,434 (0.01%) |

866,029 (0.83%) |

12,009 (0.01%) |

7,095,408 (6.79%) |

206,546 (0.2%) |

- The census figures for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes represent selective demography, as the first clause of Articles 341 and 342 specifies that Schedule status is specific to state or union territory (indicating nativeness of the region and the socio-economic disabilities arising therein), not to the whole country. For example, during the census operation, if a member of a notified community is not present in the state or union territory where the community is recognized as such, or if a member of Scheduled Castes follows religions other than Hinduism, Buddhism, or Sikhism, they are not counted as part of the Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes, but rather as part of the general population.[45][46][47]

- In the states of Arunachal Pradesh and Nagaland, and the Union Territories of Andaman and Nicobar Islands and Lakshadweep, no community is notified as Scheduled Castes; thus, there is no Scheduled Caste population.[48]

- In the states of Punjab and Haryana, and the Union Territories of Delhi, Chandigarh and Puducherry, no community is notified as Scheduled Tribes; thus, there is no Scheduled Tribe population.[48]

Provisions

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

To effectively implement the safeguards built into the Constitution and other legislation, the Constitution under Articles 338 and 338A provides for two constitutional commissions: the National Commission for Scheduled Castes,[50] and the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes.[51] The chairpersons of both commissions sit ex officio on the National Human Rights Commission.

The Constitution provides a three-pronged strategy[52] to improve the situation of SCs and STs:

- Protective arrangements: Such measures as are required to enforce equality, to provide punitive measures for transgressions, and to eliminate established practices that perpetuate inequities. A number of laws were enacted to implement the provisions in the Constitution. Examples of such laws include the Untouchability Practices Act, 1955, Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, The Employment of Manual Scavengers and Construction of Dry Latrines (Prohibition) Act, 1993, etc. Despite legislation, social discrimination and atrocities against the backward castes continued to persist.[53]

- Affirmative action: Provide positive treatment in allotment of jobs and access to higher education as a means to accelerate the integration of the SCs and STs with mainstream society. Affirmative action is popularly known as reservation. Article 16 of the Constitution states "nothing in this article shall prevent the State from making any provisions for the reservation of appointments or posts in favor of any backward class of citizens, which, in the opinion of the state, is not adequately represented in the services under the State". The Supreme Court upheld the legality of affirmative action and the Mandal Commission (a report that recommended that affirmative action not only apply to the Untouchables but the other backward class as well). However, the reservations about affirmative action were only allotted in the public sector, not the private.[54]

- Development: Provide resources and benefits to bridge the socioeconomic gap between the SCs and STs and other communities. Legislation to improve the socioeconomic situation of SCs and STs because twenty-seven percent of SC and thirty-seven percent of ST households lived below the poverty line, compared to the mere eleven percent among other households. Additionally, the backward castes were poorer than other groups in Indian society, and they suffered from higher morbidity and mortality rates.[55]

Scheduled Castes Sub-Plan

[edit]The Scheduled Castes Sub-Plan (SCSP) of 1979 mandated a planning process for the social, economic and educational development of Scheduled Castes and improvement in their working and living conditions. It was an umbrella strategy, ensuring the flow of targeted financial and physical benefits from the general sector of development to the Scheduled Castes.[56] It entailed a targeted flow of funds and associated benefits from the annual plan of states and Union Territories (UTs) in at least a proportion to the national SC population. Twenty-seven states and UTs with sizable SC populations are implementing the plan. Although the Scheduled Castes population according to the 2001 Census was 16.66 crores (16.23% of the total population), the allocations made through SCSP have been lower than the proportional population.[57] A strange factor has emerged of extremely lowered fertility of scheduled castes in Kerala, due to land reform, migrating (Kerala Gulf diaspora) and democratization of education.[58]

Issues in policy and implementation

[edit]Constitutional history

[edit]In the original Constitution, Article 338 provided for a special officer (the Commissioner for SCs and STs) responsible for monitoring the implementation of constitutional and legislative safeguards for SCs and STs and reporting to the president. Seventeen regional offices of the Commissioner were established throughout the country.[citation needed]

There was an initiative to replace the Commissioner with a committee in the 48th Amendment to the Constitution, changing Article 338. While the amendment was being debated, the Ministry of Welfare established the first committee for SCs and STs (with the functions of the Commissioner) in August 1978. These functions were modified in September 1987 to include advising the government on broad policy issues and the development levels of SCs and STs. Now it is included in Article 342.[citation needed]

In 1990, Article 338 was amended for the National Commission for SCs and STs with the Constitution (Sixty fifth Amendment) Bill, 1990.[59] The first commission under the 65th Amendment was constituted in March 1992, replacing the Commissioner for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes and the commission established by the Ministry of Welfare's Resolution of 1989. In 2003, the Constitution was again amended to divide the National Commission for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes into two commissions: the National Commission for Scheduled Castes and the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes.

Religious restriction

[edit]The Scheduled Castes, as a constitutional category in India, emerged from the practice of untouchability in the caste system associated with Hinduism. The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order of 1950 initially recognized only adherents of Hinduism for Scheduled Caste status. Amendments in 1956 and 1990 extended this recognition to those converted to Sikhism and Buddhism, respectively, based on commission reports. However, converts to Christianity, Islam, or other religions not specified in the order or its amendments are not entitled to Scheduled Caste status. Demands for such inclusion have been rejected by the Registrar General of India, which became the validating authority in 1999. Before that, state recommendations and the approval of the National Commission for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes were considered for additions, deletions, or modifications to the Presidential Order through Parliament.[60][61] As a result, individuals converted to religions not specified by the constitutional order often either avoid disclosing their actual religious beliefs or assert their previous religious identity in official records to avail social security and welfare benefits (popularly known as the Reservation) provided by the government.[62]

Area restriction

[edit]The classification of communities as Scheduled Castes, initially formalized by the British in the early 20th century under the term 'Depressed Classes', was geographically specific, with communities identified at the district or provincial level based on localized patterns of social disadvantage. After independence, this area-based framework was largely retained, as socio-economic disabilities were seen as regionally rooted by social structure.[63]

Although the intra-state area restrictions removed by the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Orders (Amendment) Act, 1976. But the inter-state area restrictions is in force. Accordingly, the lists of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are specific to each state and union territory.

Subclassification

[edit]The notified Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes were earlier regarded as homogeneous social groups for policy implementation, which resulted in disparities where some communities accessed a disproportionate share of affirmative benefits while more marginalized sections remained excluded from adequate representation. To address this, several state governments, notably Andhra Pradesh and Punjab, introduced sub-classification of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes for a more equitable distribution of affirmative measures. However, since the authority to maintain the list of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes rests with the central government, the Supreme Court struck down the sub-classification policy, emphasizing homogeneity in the context of the scheduling list.[64]

In 2024, a seven-judge bench of the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of sub-classification, clarifying that while homogeneity applies to the Presidential Scheduled List, it does not restrict state's power vis-à-vis Article 15(4), Article 16(4), and other empowering provisions in policy implementation or the distribution of welfare benefits. The decision affirmed the state's power to adopt sub-classification or other policies for the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes to ensure an equitable distribution of affirmative action benefits.[65]

See also

[edit]- Forward caste

- Inter-caste marriages in India

- List of Scheduled Tribes in India

- List of Scheduled Castes in India

- Particularly vulnerable tribal group

- Other Backward Classes

- Reservation in India

- Socio Economic Caste Census 2011

- Scheduled Areas

- Scheduled Languages

- Constitution of India § Schedules

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The first Scheduled orders were enacted by two segments, viz, 1950 order and 1951 order, enlisting 821 castes and 296 tribes in the Presidential Scheduled list. The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950, and The Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order, 1950, listed 607 castes and 241 tribes, respectively.[37][38] Similarly, The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) (Part C States) Order, 1951, and The Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) (Part C States) Order, 1951, listed 214 castes and 55 tribes. The 1950 orders applied to 16 Part A and B states: Assam, Bihar, Bombay, Madhya Pradesh, Madras, Orissa, Punjab, West Bengal, Hyderabad, Madhya Bharat, Mysore, Rajasthan, Saurashtra, and Travancore-Cochin, while the 1951 orders addressed 10 Part C states: Ajmer, Bhopal, Coorg, Himachal Pradesh, Kutch, Manipur, Tripura, and Vindhya Pradesh.

References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Constitution of India.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Constitution of India.

- ^ "Scheduled Caste Welfare – List of Scheduled Castes". Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ^ "Scheduled Castes And Scheduled Tribes". United Nations in India. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Scheduled Communities: A social Development profile of SC/ST's (Bihar, Jharkhand & West Bengal)" (PDF). Planning Commission (India). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Census of India 2011, Primary Census Abstract (28 October 2013)" (ppt). Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, Government of India. 23 September 2015. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015.

- ^ a b c Roychowdhury, Adrija (5 September 2018). "Why Dalits want to hold on to Dalit, not Harijan, not SC". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "Dalit". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- ^ Ghurye, G. S. (1980). The Scheduled Tribes of India (3rd ed.). Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-87855-692-2.

- ^ Bali, Surya (26 October 2018). "We are 'Scheduled Tribes', not 'Adivasis'". Forward Press. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- ^ Dasgupta, Sangeeta (October 2018). "Adivasi studies: From a historian's perspective". History Compass. 16 (10). doi:10.1111/hic3.12486. ISSN 1478-0542.

- ^ Union minister: Stick to SC, avoid the term 'Dalit' Archived 22 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine "Union social justice minister Thawarchand Gehlot said media should stick to the constitutional term "Scheduled Castes" while referring to Dalits as there are objections to the term to the term "Dalit" – backing the government order which has significant sections of scheduled caste civil society up in arms." Times of India 5 September 2018.

- ^ "2011 Census Primary Census Abstract" (PDF). Censusindia.gov.in. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Half of India's dalit population lives in 4 states". The Times of India. 2 May 2013. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Text of the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950, as amended". Lawmin.nic.in. Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Text of the Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order, 1950, as amended". Lawmin.nic.in. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Kumar, K Shiva (17 February 2020). "Reserved uncertainty or deserved certainty? Reservation debate back in Mysuru". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA [As on 9th December, 2020]" (PDF). Legislative Department. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Chapter- II, Social Constitutional Provisions for Protection and Development of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes" (PDF). ncsc.nic.in.

- ^ "Chapter III" (PDF). dopt.gov.in. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ a b Brochure on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in Services (PDF) (8th ed.). Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions; Department of Personnel and Training, Government of India. 1993. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 June 2024. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ Reservation Brochure (PDF) (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 February 2024. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ "Reservation Is About Adequate Representation, Not Poverty Eradication". The Wire. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ "Office of Registrar-General of India follows 'obsolete' criteria for scheduling of tribes". The Hindu. 11 January 2023. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Centre Still Employs 'Obsolete' Criteria to Categorise Groups Under ST Lists: Report". The Wire. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Inclusion Into SC List" (Press release). Press Information Bureau, Government of India. Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment. 24 February 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ^ "FAQ : National Commission for Scheduled Tribes". ncst.nic.in. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ^ Bodhi, Sainkupar Ranee; Darokar, Shaileshkumar S. (9 November 2023). "Becoming a Scheduled Tribe in India: The History, Process and Politics of Scheduling". Contemporary Voice of Dalit. doi:10.1177/2455328X231198720. ISSN 2455-328X.

- ^ Xaxa, Virginius (May 2014). Report on the high level committee on socio-economic, health and educational status of tribal communities of India (Report). Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India. hdl:2451/36746. Archived from the original on 2 February 2024. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ Khanna, Gyanvi (21 February 2024). "Schedule Tribe Member Migrating To Another State/UT Can't Claim ST Status If Tribe Isn't Notified As ST In That State/UT : Supreme Court". www.livelaw.in. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "VHP opposes SC status to religious converts who were 'historically' SCs". India Today. 16 October 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ "Reservation for Dalit Christians" (Press release). Press Information Bureau, Government of India; Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances & Pensions. 16 March 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ a b "What is India's caste system?". 20 July 2017. Archived from the original on 4 October 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ Bayly, Susan (July 1999). Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age by Susan Bayly. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521264341. ISBN 9780521264341. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Pletcher, Ken; Staff of EB (2010). "Untouchable - social class, India". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ "Civil rights | society". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ "Jati: The Caste System in India". Asia Society. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ Jyoti, Dhrubo (1 October 2019). "Gandhi, Ambedkar and the 1932 Poona Pact". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ Government of India. Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950 (PDF) (Report). Directorate of Printing.

- ^ Government of India. Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order, 1950 (Report). Extraordinary Gazette of India, 1950, No. 314. Directorate of Printing.

- ^ "THE CONSTITUTION (SCHEDULED CASTES) ORDER, 1950". lawmin.nic.in. Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 28 January 2008.

- ^ "1. THE CONSTITUTION (SCHEDULED TRIBES)". lawmin.nic.in. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017.

- ^ Metcalf, Barbara D.; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2012). A Concise History of Modern India. New York: Cambridge. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-107-67218-5.

- ^ "Basic Population Figures of India and States, 2011". Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 10 May 2022.

- ^ "Government of India, Ministry of Social Justice website". Archived from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ a b Handbook on Social Welfare Statistics (PDF) (Report). New Delhi: Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India. September 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2020.

- ^ a b Bhagat, Ram B. (2006). "Census and caste enumeration: British legacy and contemporary practice in India". Genus. 62 (2): 119–134. ISSN 0016-6987. JSTOR 29789312.

- ^ a b Nongkynrih, A K (2010). "Scheduled Tribes and the Census: A Sociological Inquiry". Economic and Political Weekly. 45 (19): 43–47. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 27807000.

- ^ a b Sahgal, Kelsey Jo Starr and Neha (29 June 2021). "Measuring caste in India". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d Social Studies Division : works and activities (details) (PDF). censusindia.gov.in (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 July 2024. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^

- "SC-14: Scheduled Caste population by religious community, 2011". Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 14 November 2019.

- "ST-14: Scheduled Tribe population by religious community, 2011". Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 14 November 2019.

- ^ "National Commission for Schedule Castes". Indiaenvironmentportal.org. Archived from the original on 31 August 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "THE CONSTITUTION (EIGHTY-NINTH AMENDMENT) ACT, 2003". Indiacode.nic.in. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ [1] Archived 8 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sengupta, Chandan (2013). Democracy, Development, and Decentralization in India: Continuing Debates. Routledge. p. 23. ISBN 978-1136198489.

- ^ Metcalf, Barbara D.; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2012). A Concise History of Modern India. New York: Cambridge. p. 274. ISBN 978-1-107-67218-5.

- ^ Sengupta, Chandan (2013). Democracy, Development and Decentralization in India: Continuing Debates. Routledge. p. 23. ISBN 9781136198489.

- ^ Sridharan, R (31 October 2005). "Letter from Joint Secretary (SP) to Planning Secretaries of All Indian States/UTs". Planning Commission (India). Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Bone, Omprakash S. (2015). Mannewar: A Tribal Community in India. Notion Press. ISBN 978-9352063444.

- ^ S., Pallikadavath; C., Wilson (1 July 2005). "A paradox within a paradox: Scheduled caste fertility in Kerala". Economic and Political Weekly. 40 (28): 3085–3093. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Constitution of India as of 29 July 2008" (PDF). The Constitution of India. Ministry of Law & Justice. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 September 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- ^ Lakshman, Abhinay (5 October 2022). "Explained | The criterion for SC status". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 11 January 2025.

- ^ Fazal, Tanweer (1 February 2017). "Scheduled Castes, reservations and religion: Revisiting a juridical debate". Contributions to Indian Sociology. 51 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1177/0069966716680429. ISSN 0069-9659.

- ^ "Community status lapses on conversion, rules Madras High Court". Thehindu.com. 24 June 2013. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Aslam, Mohammad (1990). "Scheduled Castes: Some Unresolved Problems". Journal of the Indian Law Institute. 32 (1): 110–113. ISSN 0019-5731.

- ^ PTI (4 October 2024). "Supreme Court dismisses review petitions against judgment allowing sub-classification of Scheduled Castes". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 12 January 2025.

- ^ Bakshi, Gursimran Kaur (1 August 2024). "Scheduled Castes Not A Homogeneous Class, Sub-classification One Of The Means To Achieve Substantive Equality: Supreme Court". www.livelaw.in. Retrieved 12 January 2025.

Further reading

[edit]- Mandal, Mahitosh (2022). "Dalit Resistance during the Bengal Renaissance: Five Anti-Caste Thinkers from Colonial Bengal, India". Caste: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion. 3 (1): 11–30. doi:10.26812/caste.v3i1.367. S2CID 249027627.

- Srivastava, Vinay Kumar; Chaudhary, K. (2009). "Anthropological Studies of Indian Tribes". In Atal, Yogesh singh chauhan (ed.). Sociology and Social Anthropology in India. Indian Council of Social Science Research/Pearson Education India. ISBN 9788131720349.

External links

[edit]- Ministry of Tribal Affairs – official website

- 2001 Census of India – Tables on Individual Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (archived)

- Dalit Indian Chamber of Commerce & Industry. Archived 30 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Administrative Atlas of India – 2011