West African crocodile

| West African crocodile | |

|---|---|

| |

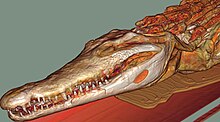

| Specimen in Bazoulé, Burkina Faso | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Archosauromorpha |

| Clade: | Archosauriformes |

| Order: | Crocodilia |

| Family: | Crocodylidae |

| Genus: | Crocodylus |

| Species: | C. suchus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Crocodylus suchus Geoffroy, 1807

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The West African crocodile, desert crocodile, or sacred crocodile (Crocodylus suchus)[2] is a species of crocodile related to, and often confused with, the larger and more aggressive Nile crocodile (C. niloticus).[3][4]

Taxonomy

[edit]

The species was named by Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire in 1807, who discovered differences between the skulls of a mummified crocodile and those of Nile crocodile (C. niloticus). This new species was, however, long afterwards regarded as a synonym of the Nile crocodile. In 2003, a study resurrected C. suchus as a valid species,[3] and this was confirmed by several other studies in 2011–2015.[5][6][7]

Despite the long history of confusion, genetic testing has revealed that the two are not particularly close. The closest relatives of the Nile crocodile are the Crocodylus species from the Americas, while the West African crocodile is basal to the clade of Nile and American crocodiles.[8][9][10]

Below is a cladogram based on a 2018 tip dating study by Lee & Yates simultaneously using morphological, molecular (DNA sequencing), and stratigraphic (fossil age) data,[9] as revised by the 2021 Hekkala et al. paleogenomics study using DNA extracted from the extinct Voay.[10]

| Crocodylinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Characteristics

[edit]

The muzzle is short and thick. The distance between the eyes and the tip of the muzzle is 1.5 to 2 times longer than the width of the muzzle at the level of the front edge of the eyes (1.2 to 1.5 times in case of juveniles). The coloration is generally brown to olive. Juveniles are paler, with black bandings, especially on the tail. Like all other species of crocodiles, the West African crocodile's eyes reflect light at night allowing it to be spotted easily through a flashlight. It is found to be active day and night. It can stay submerged underwater for more than 30 minutes, and can reach speeds of up to 30 km/h (19 mph) in short bursts. On land, it is often observed basking motionless in the sun, often with its mouth agape.[11]

Compared to the Nile crocodile, which can grow over 5 m (16 ft 5 in) in length, the West African crocodile is smaller. It typically grows between 2 and 3 m (6 ft 7 in and 9 ft 10 in) in length, with an occasional male growing over 4 m (13 ft 1 in) in rare cases.[12] Adults weigh between 90 and 250 kg (200 and 550 lb), with particularly large male specimens exceeding 300 kg (660 lb) in weight.[13][14]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The West African crocodile inhabits much of West and Central Africa, ranging east to South Sudan and Uganda, and south to Democratic Republic of the Congo (in all three countries it may come into contact with Nile crocodiles).[6][15] Other countries where it is found include Mauritania, Benin, Liberia, Guinea-Bissau, Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, Chad, Sierra Leone, the Central African Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Senegal, Mali, Guinea, Gambia, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Gabon, Togo, Ivory Coast and the Republic of Congo.[6] As late as the 1920s, museums continued to obtain West African crocodile specimens from the White Nile, but today the species has disappeared from this river.[6]

In Mauritania the species has adapted to the arid desert environment of the Sahara–Sahel by staying in caves or burrows in a state of aestivation during the driest periods, leading to the alternative common name desert crocodile. When it rains, these desert crocodiles gather at gueltas.[16][17] In much of its range, the West African crocodile may come into contact with other crocodile species and there appears to be a level of habitat segregation between them. The Nile crocodile typically prefers large seasonal rivers in savannah or grassland, while the West African crocodile generally prefers lagoons and wetlands in forested regions, at least where the two species may come into contact.[4][7] The details of this probable segregations remains to be confirmed for certain.[4] In a study of habitat use by the three crocodile species in Liberia (West African, slender-snouted and dwarf), it was found that the West African crocodile typically occupied larger, more open waterways consisting of river basins and mangrove swamps, and was the species most tolerant of brackish waters. In comparison, the slender-snouted crocodile typically occupies rivers within forest interiors, while dwarf crocodiles are distributed in smaller rivers (mainly tributaries), streams and brooks also within forested areas.[18]

Relationship with humans

[edit]The West African crocodile is less aggressive than the Nile crocodile,[4] but several attacks on humans have been recorded, including fatal ones.[19] Mauritanian traditional peoples who live in close proximity to West African crocodiles revere them and protect them from harm. This is due to their belief that, just as water is essential to crocodiles, so crocodiles are essential to the water, which would permanently disappear if they were not there to inhabit it. Here the crocodiles live in apparent peace with the humans, and are not known to attack swimmers.[16]

In ancient Egypt

[edit]

The people of ancient Egypt worshiped Sobek, a crocodile-god associated with fertility, protection, and the power of the pharaoh.[20] They had an ambivalent relationship with Sobek, as they did (and do) with C. suchus: sometimes they hunted crocodiles and reviled Sobek, and sometimes they saw him as a protector and source of pharaonic power. C. suchus was known to be more docile than the Nile crocodile and was chosen by the ancient Egyptians for spiritual rites, including mummification. DNA testing found that all sampled mummified crocodiles from the grotto of Thebes, grotto of Samoun, and Upper Egypt belonged to this species[6] whereas the ones from a burial pit at Qubbet el-Hawa are believed on the basis of anatomy to consist of a mix of the two species.[21]

Sobek was depicted as a crocodile, as a mummified crocodile, or as a man with the head of a crocodile. The center of his worship was in the Middle Kingdom city of Arsinoe in the Faiyum, known as "Crocodilopolis" by the Greeks. Another major temple to Sobek is in Kom Ombo; other temples were scattered across the country.

Historically, C. suchus inhabited the Nile in Lower Egypt along with the Nile crocodile. Herodotus wrote that the Egyptian priests were selective when picking crocodiles. Priests were aware of the difference between the two species, C. suchus being smaller and more docile, making it easier to catch and tame.[6] Herodotus also indicated that some Egyptians kept crocodiles as pampered pets. In Sobek's temple in Arsinoe, a crocodile was kept in the pool of the temple, where it was fed, covered with jewelry, and worshipped. When the crocodiles died, they were embalmed, mummified, placed in sarcophagi, and then buried in a sacred tomb. Many mummified C. suchus specimens and even crocodile eggs have been found in Egyptian tombs.

Spells were used to appease crocodiles in ancient Egypt, and even in modern times Nubian fishermen stuff and mount crocodiles over their doorsteps to ward against evil.

In captivity

[edit]

The West African crocodile only received wider recognition as a valid species in 2011. Consequently, captives have typically been confused with other species, especially the Nile crocodile.[15] In Europe, breeding pairs of West African crocodiles live in Copenhagen Zoo, Lyon Zoo and Vivarium de Lausanne, and offspring of the first pair are in Dublin Zoo and Kristiansand Zoo.[23] A study in 2015 that included 16 captive "Nile crocodiles" in 6 US zoos (almost a quarter of the "Nile crocodiles" in AZA zoos) found that all but one were actually West African crocodiles.[15]

References

[edit]- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ Crocodylus suchus, The Reptile Database

- ^ a b Schmitz, A.; Mausfeld, P.; Hekkala, E.; Shine, T.; Nickel, H.; Amato, G. & Böhme, W. (2003). "Molecular evidence for species level divergence in African Nile crocodiles Crocodylus niloticus (Laurenti, 1786)". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 2 (8): 703–12. Bibcode:2003CRPal...2..703S. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2003.07.002.

- ^ a b c d Pooley, S. (2016). "A Cultural Herpetology of Nile Crocodiles in Africa". Conservation & Society. 14 (4): 391–405. doi:10.4103/0972-4923.197609.

- ^ Nile crocodile is two species, Nature.com

- ^ a b c d e f Hekkala, E.; Shirley, M.H.; Amato, G.; Austin, J.D.; Charter, S.; Thorbjarnarson, J.; Vliet, K.A.; Houck, M.L.; Desalle, R. & Blum, M.J. (2011). "An ancient icon reveals new mysteries: Mummy DNA resurrects a cryptic species within the Nile crocodile". Molecular Ecology. 20 (20): 4199–4215. Bibcode:2011MolEc..20.4199H. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05245.x. PMID 21906195.

- ^ a b Cunningham, S.W. (2015), Spatial and genetic analyses of Africa's sacred crocodile: Crocodylus suchus, ETD Collection for Fordham University

- ^ Robert W. Meredith; Evon R. Hekkala; George Amato; John Gatesy (2011). "A phylogenetic hypothesis for Crocodylus (Crocodylia) based on mitochondrial DNA: Evidence for a trans-Atlantic voyage from Africa to the New World". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 60 (1): 183–191. Bibcode:2011MolPE..60..183M. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2011.03.026. PMID 21459152.

- ^ a b Michael S. Y. Lee; Adam M. Yates (27 June 2018). "Tip-dating and homoplasy: reconciling the shallow molecular divergences of modern gharials with their long fossil". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 285 (1881). doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.1071. PMC 6030529. PMID 30051855.

- ^ a b Hekkala, E.; Gatesy, J.; Narechania, A.; Meredith, R.; Russello, M.; Aardema, M. L.; Jensen, E.; Montanari, S.; Brochu, C.; Norell, M.; Amato, G. (27 April 2021). "Paleogenomics illuminates the evolutionary history of the extinct Holocene "horned" crocodile of Madagascar, Voay robustus". Communications Biology. 4 (1): 505. doi:10.1038/s42003-021-02017-0. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC 8079395. PMID 33907305.

- ^ Trape, Jean-François; Trape, Sébastien; Chirio, Laurent (2012). Lézards, crocodiles et tortues d'Afrique occidentale et du Sahara (in French). IRD Editions. p. 420. ISBN 978-2-7099-1726-1.

- ^ Trape, Jean-François; Trape, Sébastien; Chirio, Laurent (2012). Lézards, crocodiles et tortues d'Afrique occidentale et du Sahara (in French). IRD Editions. p. 420. ISBN 978-2-7099-1726-1.

- ^ Molinaro, Holly Grace; Anderson, Gen S.; Gruny, Lauren; Sperou, Emily S.; Heard, Darryl J. (January 2022). "Use of Blood Lactate in Assessment of Manual Capture Techniques of Zoo-Housed Crocodilians". Animals. 12 (3): 397. doi:10.3390/ani12030397. PMC 8833426. PMID 35158720.

- ^ Sonhaye-Ouyé, Abré; Hounmavo, Amétépé; Assou, Delagnon; Afi Konko, Florence; Segniagbeto, Gabriel H.; Ketoh, Guillaume K.; Funk, Stephan M.; Dendi, Daniele; Luiselli, Luca; Fa, Julia E. (June 2022). "Wild meat hunting levels and trade in a West African protected area in Togo". African Journal of Ecology. 60 (2): 153–164. Bibcode:2022AfJEc..60..153S. doi:10.1111/aje.12983. S2CID 247728849.

- ^ a b c Shirley; Villanova; Vliet & Austin (2015). "Genetic barcoding facilitates captive and wild management of three cryptic African crocodile species complexes". Animal Conservation. 18 (4): 322–330. Bibcode:2015AnCon..18..322S. doi:10.1111/acv.12176. S2CID 82155811.

- ^ a b Mayell, H. (18 June 2002). "Desert-Adapted Crocs Found in Africa". National Geographic.com. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Campos; Martínez-Frería; Sousa & Brito (2016). "Update of distribution, habitats, population size, and threat factors for the West African crocodile in Mauritania". Amphibia-Reptilia. 2016 (3): 2–6. doi:10.1163/15685381-00003059.

- ^ Kofron, C. P. (2009). "Status and habitats of the three African crocodiles in Liberia". Journal of Tropical Ecology. 8 (3): 265–273. doi:10.1017/s0266467400006490. S2CID 85775155.

- ^ Sideleau, B.; Shirley, M. "West African crocodile". CrocBITE, Worldwide Crocodilian Attack Database. Charles Darwin University, Northern Territory, Australia. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ "Sobek, God of Crocodiles, Power, Protection and Fertility..." Archived from the original on 25 July 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- ^ Jones, Sam (18 January 2023). "10 Mummified Crocodiles Emerge From an Egyptian Tomb". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ Larsen, H. (5 January 2014), Københavnerkrokodiller har skiftet art, Politiken

- ^ Ziegler, T.; S. Hauswaldt & M. Vences (2015). "The necessity of genetic screening for proper management of captive crocodile populations based on the examples of Crocodylus suchus and C. mindorensis". Journal of Zoo and Aquarium Research. 3 (4): 123–127.