Sheba

It is requested that the page history of Sabaeans be merged into the history of this page because recent merge This action must be performed by an administrator or importer (compare pages).

Administrators: Before merging the page histories, read the instructions at Wikipedia:How to fix cut-and-paste moves carefully. An incorrect history merge is very difficult to undo. Also check Wikipedia:Requests for history merge for possible explanation of complex cases. |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Arabic. (September 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Kingdom of Sheba Kingdom of Saba | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ~1000 BCE–275 CE | |||||||

Map of Sheba in blue in South Arabia | |||||||

| Capital | Marib Sanaa[1][2] | ||||||

| Official languages | Sabaic | ||||||

| Religion | Arabian polytheism | ||||||

| Demonym(s) | Sabaeans | ||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||

| Mukarrib (list of rulers) | |||||||

• 700–680 BCE | Karibi-ilu | ||||||

• 620–600 BCE | Karib'il Watar | ||||||

• 60–20 BCE | Ilīsharaḥ Yaḥḍub I | ||||||

| History | |||||||

• Established | ~1000 BCE | ||||||

• Disestablished | 275 CE | ||||||

| |||||||

| Today part of | |||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Yemen |

|---|

|

|

Sheba,[a][3][4][5][6] or Saba, was an ancient South Arabian kingdom in modern-day Yemen[7] whose inhabitants were known as the Sabaeans.[b] Modern historians agree that the heartland of the Sabaean civilization was located in the region around Marib and Sirwah.[8][9] They later expanded their presence into parts of North Arabia[9] and the Horn of Africa, in modern-day Ethiopia.[10]

The Sabaeans founded the Kingdom of Saba in the late second or first millennium BCE,[11][12] considered by South Arabians and the first Abyssinian kingdoms to be the birthplace of South Arabian civilization, and whose name carried prestige.[13] The spoken language of the Sabaeans was Sabaic, a variety of Old South Arabian.[14] The Kingdom of Saba was originally confined to the region of Marib (its capital) and its surroundings. At its height, it encompassed much of southwest Arabia, before eventually declining to the regions of Marib and its secondary capital, Sanaa, founded in the 1st century CE, the capital of Yemen today. Around 275 CE, the Saba civilization came to an end after being annexed by the neighbouring Himyarite Kingdom.[1]

Saba existed alongside several neighboring kingdoms in ancient South Arabia. To their north was the Kingdom of Ma'in, and to their east was the Kingdom of Qataban and the Kingdom of Hadhramaut. The Sabaeans, like the other Yemenite kingdoms of their time, were involved in the extremely lucrative spice trade, especially including frankincense and myrrh.[15] They left behind many inscriptions in the monumental Ancient South Arabian script as well as numerous documents in the related cursive Zabūr script. They also interacted with the societies in the Horn of Africa where they left numerous traces, including inscriptions and temples that date back to the Sabaean colonization of Africa.[16][17][18][19]

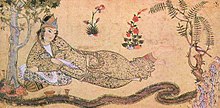

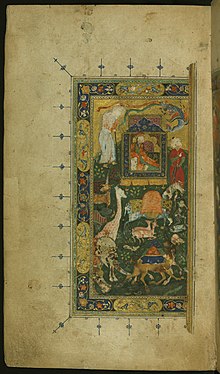

This kingdom came to play an important role in the Hebrew Bible and appears in the Quran (not to be confused with the Quranic Sabians).[20][21][22] The story of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba have raised questions of historicity, based on if Saba was capable of such a lucrative involvement in incense trade as early in its history as the time of Solomon.[23] Traditions about Saba particularly feature in the tradition of Orthodox Tewahedo in today's Yemen and is also asserted as the home of the Queen of Sheba, who is left unnamed in Jewish texts but is known as Makeda in Ethiopian texts and as Bilqīs in Arabic texts. According to the Jewish historian Josephus, Sheba was the home of Princess Tharbis, who is said to have been the wife of Moses before he married Zipporah. Some Islamic exegetes identified Sheba with the People of Tubba.[24]

Sources

[edit]The Sabaic language was written down in a corresponding Sabaic script, with the earliest evidence of this dating to the 11th to 10th centuries BCE.[25] The Sabaic tradition has left behind a sizable epigraphic record. Of the 12,000 corresponding Ancient South Arabian inscriptions, 6,500 of them are in Sabaic. The region first sees a continuous record of epigraphic documentation in the 8th century BCE, which lasts until the 9th century CE, long after the fall of the Sabaean kingdom and covering a time range of about a millennium and a half and constituting the main source of information about the Sabaeans.[26]

External information about the Sabaeans comes first from Akkadian cuneiform texts starting in the 8th century BCE. Less important are brief reports from the Bible about correspondence between Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. While the story is of debatable historicity, knowledge of the Sabaeans as merchant peoples indicates that some level of trade between the regions was underway in this time. After the campaigns of Alexander the Great, South Arabia became a hub of trade routes linking the broader geopolitical realm with India. As such, information about the region begins to appear among Greco-Roman observers and information becomes more concrete. The most important accounts about South Arabia are from Eratosthenes, Strabo, Theophrastus, Pliny the Elder, an anonymous first-century seafarming manual called the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea concerning the politics and topography of South Arabian coasts, the Ecclesiastical History by Philostorgius, and Procopius.[27]

History

[edit]Formative period

[edit]The formative phase of the Sabaeans, or the period prior to the emergence of urban cultures in South Arabia, can be placed the latter part of the 2nd millennium BCE, and was completed by the 10th century BCE, where a fully developed script appears in combination with the technological prowess to construct complex architectural complexes and cities. There is some debate as to the degree to which the movement out of the formative phase was channeled by endogenous processes, or the transfer or technologies from other centers, perhaps via trade and immigration.[28][29]

Originally, the Sabaeans were part of "communities" (called shaʿbs) on the edge of the Sayhad desert. Very early, at the beginning of the 1st millennium BC, the political leaders of this tribal community managed to create a huge commonwealth of shaʿbs occupying most of South Arabian territory and took on the title "Mukarrib of the Sabaeans".[30]

Emergence

[edit]

The origin of the Sabaean Kingdom is uncertain and is a point of disagreement among scholars,[31] with estimates placing it around 1200 BCE,[32] by the 10th century BCE at the latest,[33] or a period of flourishing that only begins from the 8th century BCE onwards.[34] Once the polity had been established, Sabaean kings referred to themselves by the title Mukarrib.

First Sabaean period (8th — 1st centuries BCE)

[edit]The first major phase of the Sabaean civilization lasted between the 8th and 1st centuries BCE. The 8th century is when the first stone inscriptions appear, and when leaders are already being called by the title Mukarrib ("federator"). Due to this convention, this era can also be called the "Mukarrib period". The title mukarrib was more prestigious than that of mlk ("king") and was used to refer to someone that extended hegemony over other tribes and kingdoms.[1] During this time, Sabaean kings were referred to by a name followed by an epithet, each chosen by a set of six and four possibilities respectively. The possible names chosen from were Dhamar'ali, Karib'il, Sumhu'alay, Yada"il, Yakrubmalik and Yitha'amar. The possible epithets were Bayan, Dharih, Watar and Yanu. This gives rise to difficulties in reconstructing the chronology of the Kingdom of Saba as it is not easy to tell apart different kings given the same name or place the different kings along a relative chronology, even though many of them are known from the epigraphic record.[35]

The first Sabaean period was dominated by a caravan economy that had market ties with the rest of the Near East. Its first major trading partners were at Khindanu and the Middle Euphrates. Later, this moved to Gaza during the Persian period, and finally, to Petra in Hellenistic times. The South Arabian deserts gave rise to important aromatics which were exported in trade, especially frankincense and myrrh. It also acted as an intermediary for overland trade with neighbours in Africa and further off from India. Saba was a theocratic monarchy with a common cult surrounding their national god, Almaqah. Four other deities were also worshipped: Athtar, Haubas, Dhat-Himyam, and Dhat-Badan.[36]

By the end of the 1st millennium BCE, several factors came together and brought about the decline of the Sabaean state and civilization.[37] The biggest challenge came from the expansion of the Roman Republic. The Republic conquered Syria in 63 BCE and Egypt in 30 BCE, diverting Saba's overland trade network. The Romans then attempted to conquer Saba around 26/25 BCE with an army sent out under the command of the governor Aelius Gallus, setting Marib to siege. Due to heat exhaustion, the siege had to be quickly given up. However, after conquering Egypt, the overland trade network was redirected to maritime routes, with an intermediary port chosen with Bir Ali (then called Qani). This port was part of the Kingdom of Hadhramaut, far from Sabaean territory.[38] Greatly economically weakened, the Kingdom of Saba was soon annexed by the Himyarite Kingdom, bringing this period to a close.[39]

Second Sabaean period (1st – 3rd centuries CE)

[edit]After the disintegration of the first Himyarite Kingdom, Sabaean Kingdom reappeared.[39] This kingdom was different from the earlier one in many important respects.[40] The most significant change is that local power dynamics had shifted from the oasis cities on the desert margin, like Marib, to the highlands. Despite liberating itself from Himyar by around 100 CE, leaders of Himyar continued calling themselves the "king of Saba", as they had been doing during the period in which they ruled the region, to assert their legitimacy over the territory.[38]

The Kingdom fell after a long but sporadic civil war between several Yemenite dynasties claiming kingship,[41][42] and the late Himyarite Kingdom rose as victorious.[26] Sabaean kingdom was finally permanently conquered by the Ḥimyarites around 275 CE.

Conquests

[edit]The major conquests in Saba were driven by the exploits of Karib'il Watar. Karib'il conquered all surrounding neighbours, including the Awsan, Qataban, and Hadhramaut. Karib'il's exploits largely unified Yemen.[43]

Conquest of Awsan

[edit]

The Kingdom of Awsan flourished in the 8th and 7th centuries BCE and in this time was a significant regional competitor with the Kingdom of Saba. However, during the reigns of the Sabaean king Karib'il Watar and the Awsan king Murattaʿ, the two engaged in a military conflict that ended with the obliteration of the Kingdom of Awsan. The tribal elite leading Awsan were slaughtered, and the palace of Murattaʿ was destroyed, as well as their temples and inscriptions. The wadi was depopulated, which is reflected in the abandonment of the wadi. Sabaean inscriptions claim that 16,000 were killed and 40,000 prisoners were taken. This may not have been a significant exaggeration, as the Awsan kingdom disappeared as a political entity from the historical record for five or six centuries.[44] This event is documented in a lengthy inscription commissioned by Karib'il Watar called RES 3945, which records eight campaigns. The defeat of Awsan is documented in the description of the second campaign.[45]

Ethio-Sabaean kingdom (800 – 300 BCE)

[edit]Around 800 BCE, the Sabaeans conquered a region in the Horn of Africa that included parts of Eritrea and the Tigray Region of Ethiopia. This event, known as the Sabaean colonization of Africa, resulted in the emergence of the Ethio-Sabaean kingdom of D'iamat. Large-scale trade occurred between South Arabia and Africa. The national Sabaean god, Almaqah, had a grand temple constructed at the site of Yeha in what is now northern Ethiopia. In addition to religion, artistic styles also spread into Ethiopia. Even after the collapse of D'iamat, population groups continued to migrate from Saba (and Himyar) into Ethiopia. Ethiopia only began to establish its own position of power when the Kingdom of Aksum arose in the 1st century CE.[46]

Urban centers

[edit]Marib

[edit]In the Kingdom of Saba, Marib was an oasis and one of the main urban centers of the kingdom. It was by far the largest ancient city from ancient South Arabia, if not its only real city.[47] Marib was located at the precise point that the wadi (of Wadi Dhana) emerges from the Yemeni highlands.[1] It was located along what was called the Sayhad desert by medieval Arab geographers, but is now known as Ramlat al-Sab'atayn. The city lies 135 km east of Sanaa, which is the capital of Yemen today, found in the Wadi Dana delta, in the northwestern central Yemeni highlands. The oasis is about 10,000 hectares and the course of the wadi divides it into two: a northern and a southern half, which was already spoken of in records from the 8th century BCE, and this prominent feature may have been remembered as late as in the time of the Quran (34:15). A wall was built around Marib, and 4 km of that wall is still standing today. The wall, in some places, can be as much as 14 m thick. The wall encloses a 100-hectare area shaped like a trapezoid, and the settlement appears to have been created in the late second millennium BCE. Archaeological inquiries have uncovered a settlement plan that allocated different areas for different tasks. There is one residential division to the city. Another division containing sacred buildings but no residential development was probably a storage area for trade caravans and the shipment of goods. Immediately to the west was the great city temple Harun, dedicated to the national Sabaean god, Almaqah.[48]

A processional road, known from inscriptions but not yet discovered, led from the Harun temple to the Temple of Awwam, 3.5 km to the southeast of Marib, which is both the main temple for the god Almaqah in the Kingdom of Saba and the largest temple complex known from South Arabia. Hundreds of inscriptions are known from the Awwam Temple, and these documents form the basis from which the political history of South Arabia thus far reconstructable from in the first few centuries of the Christian era. The enclosure was built in the 7th century BCE according to a monumental inscription from the time of Yada'il Darih. South of the temple wall is a 1.5-hectare necropolis, in which it is estimated that about 20,000 people have been buried over a time period covering about a millennium.[49]

Shortly west of the Awwam Temple is another major temple in the southern oasis dedicated to Almaqah, which has been fully excavated and is the best studied temple to date from South Arabia: the Barran Temple. It is evident that predecessors to the Barran Temple went back to the 10th century BCE. The construction history is properly documented by inscriptions in the area. The temple was destroyed shortly before the beginning of the Christian era. The exact cause is unknown, but it may have been linked to an (ultimately unsuccessful) siege of South Arabia by the Romans, under the leadership of the governor Aelius Gallus in 25/24 BCE. Inscriptions attest other temples dedicated to other gods but these have not yet been discovered archaeologically.[50]

The Marib Dam was one of the most well-known architectural complexes from Yemen, and was even mentioned in the Quran (34:16), and this construction made it possible to irrigate the 10,000 hectares of the Marib oasis.[47] The dam is located 10 km west of the main settlement. The dam successfully delegates and distributes water from the biannual monsoon rains into two main channels, which move away from the wadi and into fields through a highly dispersive system. This allowed the region to convert alluvial loads into fertile soils and so cultivate various crops. It took until the 6th century BCE for the full closure to be accomplished. The system required constant maintenance, and two major dam failures are reported from 454/455 and 547 CE. However, as political authority weakened over the course of the 6th century CE, maintenance efforts could not be sustained. The dam was therefore breached and the oasis was temporarily abandoned by the early seventh century.[51]

Sirwah

[edit]The second Sabaean urban center was Sirwah. The two cities are connected by an ancient road. A wall had been built around Sirwah by the 10th century BCE. Much smaller than Marib, the city of Sirwah is 3.8 hectares in size, but it is archaeologically well-understood. The main buildings at the site are administrative and sacred buildings. Some buildings demonstrate that Sirwah acted as a transshipment point for trade goods. Legal documents show that Sirwah engaged in trade with Qataban to the southeast and the highlands around Sanaa to the west. Despite the urban area being limited, a significant portion of the space was allocated to sacred buildings. This has led some people to think that Sirwah acted as a religious center. The Great Temple of Almaqah is the most notable one, besides which, four other sacred buildings are known. One of these buildings was probably devoted to the female deity Atarsamain. Yada'il Darih, already a temple builder at the Awwam Temple in Marib, also fundamentally remodelled the Alwaqah Temple in the mid-7th century BCE. Inside the temple, in the area that is most cultically important, stands two parallel monumental inscriptions recording the lifetime achievements of two rulers: Yatha' Amar Watar and Karib'il Watar, who reigned in the late 8th and early 7th centuries BCE. The description in these records begins with comments on sacrifices made to the Sabaean deities, and then mostly delve into military campaigns in meticulous detail. At the end, the inscriptions record purchases of cities, landscapes, and fields.[52]

Legacy

[edit]Islamic tradition

[edit]The story of the visit of the Queen of Sheba to Solomon story is discussed in Quran 27:15–44.[53]

The name of Saba' is mentioned in the Qur'an in surah al-Maeeda 5:69, an-Naml 27:15-44 and Sabaʾ 34:15-17. Their mention in surah al-Naml refers to the area in the context of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, whereas their mention in surah Sabaʾ refers to the Flood of the Dam, in which the historic dam was ruined by flooding. As for the phrase Qawm Tubbaʿ "People of Tubbaʿ", which occurs in surah ad-Dukhan 44:37 and Qaf 50:12-14, Tubbaʿ was a title for the kings of Saba', like for Himyarites.[54]

Muslim commentators such as al-Tabari, al-Zamakhshari, al-Baydawi supplement the story at various points. The Queen's name is given as Bilqis, probably derived from Greek παλλακίς or the Hebraised pilegesh, "concubine".[55] According to some he then married the Queen, while other traditions assert that he gave her in marriage to a tubba of Hamdan.[56] According to the Islamic tradition as represented by al-Hamdani, the queen of Sheba was the daughter of Ilsharah Yahdib, the Himyarite king of Najran.[57]

Although the Quran and its commentators have preserved the earliest literary reflection of the complete Bilqis legend, there is little doubt among scholars that the narrative is derived from a Jewish Midrash.[56]

Bible stories of the Queen of Sheba and the ships of Ophir served as a basis for legends about the Israelites traveling in the Queen of Sheba's entourage when she returned to her country to bring up her child by Solomon.[58] There is a Muslim tradition that the first Jews arrived in Yemen at the time of King Solomon, following the politico-economic alliance between him and the Queen of Sheba.[59]

The Ottoman scholar Mahmud al-Alusi compared the religious practices of South Arabia to Islam in his Bulugh al-'Arab fi Ahwal al-'Arab.

The Arabs during the pre-Islamic period used to practice certain things that were included in the Islamic Sharia. They, for example, did not marry both a mother and her daughter. They considered marrying two sisters simultaneously to be the most heinous crime. They also censured anyone who married his stepmother, and called him dhaizan. They made the major hajj and the minor umra pilgrimage to the Ka'ba, performed the circumambulation around the Ka'ba tawaf, ran seven times between Mounts Safa and Marwa sa'y, threw rocks and washed themselves after sexual intercourse. They also gargled, sniffed water up into their noses, clipped their fingernails, removed all pubic hair and performed ritual circumcision. Likewise, they cut off the right hand of a thief and stoned Adulterers.[60]

According to the medieval religious scholar al-Shahrastani, Sabaeans accepted both the sensible and intelligible world. They did not follow religious laws but centered their worship on spiritual entities.[61]

Ethiopian and Yemenite tradition

[edit]In the medieval Ethiopian cultural work called the Kebra Nagast, Sheba was located in Ethiopia.[62] Some scholars therefore point to a region in the northern Tigray and Eritrea which was once called Saba (later called Meroe), as a possible link with the biblical Sheba.[63] Donald N. Levine links Sheba with Shewa (the province where modern Addis Ababa is located) in Ethiopia.[64]

Traditional Yemenite genealogies also mention Saba, son of Qahtan; Early Islamic historians identified Qahtan with the Yoqtan (Joktan) son of Eber (Hūd) in the Hebrew Bible (Gen. 10:25-29). James A. Montgomery finds it difficult to believe that Qahtan was the biblical Joktan based on etymology.[65][66]

See also

[edit]- Haubas

- List of rulers of Saba and Himyar

- Qataban

- Old South Arabian, a language

- Ancient history of Yemen

- Ancient South Arabian art

- Azd

- Hamdan tribe

- Minaean Kingdom

- Rada'a

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Robin 2002, p. 51.

- ^ Hoyland 2002, p. 47.

- ^ The Torah, the Gospel, and the Qur'an: Three Books, Two Cities, One Tale — Anton Wessels Archived 2018-02-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ A Brief History of Saudi Arabia — James Wynbrandt — Page11. Archived 2018-02-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Perished Nations — Hârun Yahya — Page113. Archived 2018-02-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hellenistic Economies — Zofia H. Archibald, — Page123. Archived 2018-02-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The kingdoms of ancient South Arabia". British Museum. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved 2013-02-22.

- ^ Michael Wood, "The Queen Of Sheba", BBC History.

- ^ a b Nebes 2023, p. 299.

- ^ Nebes 2023, pp. 348, 350.

- ^ Quran 27:6-93

- ^ Quran 34:15-18

- ^ Robin 2002, p. 56–57.

- ^ Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity, 1991.

- ^ "Yemen | Facts, History & News". InfoPlease.

- ^ The Athenaeum. J. Lection. 1894. p. 88.

- ^ Poluha, Eva (2016-01-28). Thinking Outside the Box: Essays on the History and (Under)Development of Ethiopia. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1-5144-2223-6.

- ^ The Babylonian and Oriental Record. D. Nutt. 1894. p. 107.

- ^ Japp, Sarah; Gerlach, Iris; Hitgen, Holger; Schnelle, Mike (2011). "Yeha and Hawelti: cultural contacts between Sabaʾ and DʿMT — New research by the German Archaeological Institute in Ethiopia". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 41: 145–160. ISSN 0308-8421. JSTOR 41622129.

- ^ Burrowes, Robert D. (2010). Historical Dictionary of Yemen. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 319. ISBN 978-0810855281.

- ^ St. John Simpson (2002). Queen of Sheba: treasures from ancient Yemen. British Museum Press. p. 8. ISBN 0714111511.

- ^ Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson (2003). On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 116. ISBN 0802849601.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2007). David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible's Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition. Simon & Schuster. p. 171.

- ^ Wheeler, Brannon M. (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 166. ISBN 0-8264-4956-5 – via Google Books.

- ^ Stein 2020, p. 338.

- ^ a b Nebes 2023, p. 303.

- ^ Nebes 2023, p. 308–311.

- ^ Nebes 2023, p. 330–332.

- ^ Robin 2002, p. 57–58.

- ^ Korotayev 1996, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Nebes 2023, p. 330.

- ^ Kenneth A. Kitchen The World of "Ancient Arabia" Series. Documentation for Ancient Arabia. Part I. Chronological Framework and Historical Sources p.110

- ^ Nebes 2023, p. 332.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher, David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible's Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition, p. 171

- ^ Robin 2002, p. 52.

- ^ Robin 2002, p. 51–52.

- ^ Korotayev 1995, p. 98.

- ^ a b Robin 2002, p. 53.

- ^ a b Korotayev 1996.

- ^ KOROTAYEV, A. (1994). Middle Sabaic BN Z: clan group, or head of clan?. Journal of semitic studies, 39(2), 207-219.

- ^ Muller, D. H. (1893), Himyarische Inschriften [Himyarian inscriptions] (in German), Mordtmann, p. 53

- ^ Javad Ali, The Articulate in the History of Arabs before Islam, Volume 2, p. 420

- ^ Robin 2002, p. 58.

- ^ Nebes 2023, p. 342–343.

- ^ Robin 2015, p. 119.

- ^ Schulz 2024, p. 131.

- ^ a b Robin 2002, p. 54.

- ^ Nebes 2023, p. 314–317.

- ^ Nebes 2023, p. 318–320.

- ^ Nebes 2023, p. 320–323.

- ^ Nebes 2023, p. 323–326.

- ^ Nebes 2023, p. 326–330.

- ^ Wheeler, Brannon (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-8264-4956-6.

- ^ Wheeler, Brannon M. (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 166. ISBN 0-8264-4956-5 – via Google Books.

- ^ Georg Freytag (1837), "ﺑَﻠٔﻘَﻊٌ", Lexicon arabico-latinum, Schwetschke, p. 44a

- ^ a b E. Ullendorff (1991), "BILḲĪS", The Encyclopaedia of Islam, vol. 2 (2nd ed.), Brill, pp. 1219–1220

- ^ A. F. L. Beeston (1995), "SABAʾ", The Encyclopaedia of Islam, vol. 8 (2nd ed.), Brill, pp. 663–665

- ^ Haïm Zʿew Hirschberg; Hayyim J. Cohen (2007), "ARABIA", Encyclopaedia Judaica, vol. 3 (2nd ed.), Gale, p. 295

- ^ Yosef Tobi (2007), "QUEEN OF SHEBA", Encyclopaedia Judaica, vol. 16 (2nd ed.), Gale, p. 765

- ^ al-Alusi, Muhammad Shukri. Bulugh al-'Arab fi Ahwal al-'Arab, Vol. 2. p. 122.

- ^ Walbridge, John (1998). "Explaining Away the Greek Gods in Islam". Journal of the History of Ideas. 59 (3): 389–403. doi:10.2307/3653893. ISSN 0022-5037.

- ^ Edward Ullendorff, Ethiopia and the Bible (Oxford: University Press for the British Academy, 1968), p. 75

- ^ The Quest for the Ark of the Covenant: The True History of the Tablets of Moses, by Stuart Munro-Hay

- ^ Donald N. Levine, Wax and Gold: Tradition and Innovation in Ethiopia Culture (Chicago: University Press, 1972).

- ^ Maalouf, Tony (2003). "The Unfortunate Beginning (Gen. 16:1–6)". Arabs in the Shadow of Israel: The Unfolding of God's Prophetic Plan for Ishmael's Line. Kregel Academic. p. 45. ISBN 9780825493638. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

This view is largely based on the claim of Muslim Arab historians that their oldest ancestor is Qahtan, whom they identify as the biblical Joktan (Gen. 10:25–26). Montgomery finds it difficult to reconcile Joktan with Qahtan based on etymology.

- ^ Maqsood, Ruqaiyyah Waris. "Adam to the Banu Khuza'ah". Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-08-15.

Sources

[edit]- Hoyland, Robert (2002). Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam. Routledge.

- Korotayev, Andrey (1995). Ancient Yemen. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-922237-1.

- Korotayev, Andrey (1996). Pre-Islamic Yemen. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 3-447-03679-6.

- Nebes, Norbert (2023). "Early Saba and Its Neighbors". In Radner, Karen; Moeller, Nadine; Potts, D. T. (eds.). The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: The Age of Persia. Vol. 5. Oxford University Press. pp. 299–375. ISBN 978-0-19-068766-3.

- Robin, Christian Julien (2002). "Saba' and the Sabaeans". In Simpson, John (ed.). Queen of Sheba, Treasures from Ancient Yemen. The British Museum Press. pp. 51–58.

- Robin, Christian Julien (2015). "Before Ḥimyar: Epigraphic Evidence for the Kingdoms of South Arabia". In Fisher, Greg (ed.). Arabs and Empires Before Islam. Oxford University Press. pp. 90–126.

- Schulz, Regine (2024). "South Arabia and Its Relations with Ethiopia: A Reciprocal History". In Sciacca, Christine (ed.). Ethiopia at the Crossroads. Yale University Press. pp. 127–133.

- Stein, Peter (2020). "Ancient South Arabian". In Hasselbach-Andee, Rebecca (ed.). A Companion to Ancient Near Eastern Languages. Wiley. pp. 337–353.

Further reading

[edit]- Bafaqīh, M. ‛A., L'unification du Yémen antique. La lutte entre Saba’, Himyar et le Hadramawt de Ier au IIIème siècle de l'ère chrétienne. Paris, 1990 (Bibliothèque de Raydan, 1).

- Klotz, David (2015). "Darius I and the Sabaeans: Ancient Partners in Red Sea Navigation". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 74 (2): 267–280. doi:10.1086/682344. S2CID 163013181.

- Ryckmans, J., Müller, W. W., and ‛Abdallah, Yu., Textes du Yémen Antique inscrits sur bois. Louvain-la-Neuve, 1994 (Publications de l'Institut Orientaliste de Louvain, 43).

- Saba' (Encyclopædia Britannica)

External links

[edit]- "Queen of Sheba mystifies at the Bowers" – UC Irvine news article on Queen of Sheba exhibit at the Bowers Museum

- "A Dam at Marib" from the Saudi Aramco World online – March/April 1978

- Queen of Sheba Temple restored (2000, BBC)

- William Leo Hansberry, E. Harper Johnson, "Africa's Golden Past: Queen of Sheba's true identity confounds historical research", Ebony, April 1965, p. 136 — thorough discussion of previous scholars associating Biblical Sheba with Ethiopia.

- S. Arabian "Inscription of Abraha" in the Sabaean language Archived 2016-02-03 at the Wayback Machine, at Smithsonian/NMNH website