Robert Daniel Lawrence

Robert Daniel Lawrence | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Robert "Robin" Daniel Lawrence 18 November 1892 |

| Died | 27 August 1968 (aged 75) |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation(s) | physician at King’s College Hospital, London |

| Known for | early recipient of insulin injections |

| Notable work | founder, British Diabetic Association |

Robert "Robin" Daniel Lawrence (18 November 1892 – 27 August 1968) was a British physician at King’s College Hospital, London. He was diagnosed with diabetes in 1920 and became an early recipient of insulin injections in the UK in 1923. He devoted his professional life to the care of people with diabetes and is remembered as the founder of the British Diabetic Association.

Early life

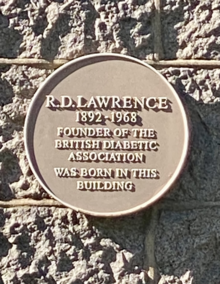

[edit]R.D. Lawrence, better known as Robin Lawrence was born at 10 Ferryhill Place, Aberdeen, a four-storied granite terraced dwelling in a quiet tree-lined street in what was then an affluent middle-class area of the city. He was the second son of Thomas and Margaret Lawrence. His father was a prosperous brush manufacturer, whose firm supplied all the brushes to Queen Victoria and her heirs at Balmoral. At the age of ten, the family moved to a larger more imposing newly built granite building, 8 Rubislaw Den North, then on the outskirts of the town and now the most prestigious housing area in the city.[1] He was within five minutes cycling distance of the Aberdeen Grammar School which he attended from 1900–09. He had a good scholastic record but also excelled at sport. In his later years there, he represented the school at rugby and cricket and won prizes for swimming. Throughout his school years, his name featured regularly for different events at the annual school sports including in 1907, second prize for the bizarre event "Sword Feats on Bicycle"![2]

He matriculated aged eighteen and went to Aberdeen University to take an MA in French and English. After graduation, he briefly worked in an uncle's drapery shop in Glasgow but gave this up after just a few weeks, returning to Aberdeen where he enrolled back at Aberdeen University to study Medicine. He had a brilliant undergraduate career winning gold medals in Anatomy (2), Clinical Medicine and Surgery and graduated "with honours" in 1916.[3] During his second year, on the advice of his anatomy professor he sat and passed the primary FRCS examination in London. He gave up rugby when a student, but represented the university at both hockey and tennis. He was also President of the Students' Representative Council.

Upon graduation, Lawrence immediately joined the RAMC and after six months home service, served on the Indian Frontier until invalided home in 1919 with dysentery and was discharged with the final rank of captain.[4] After a few weeks convalescing at home and fishing, he went to London and obtained the post of House Surgeon in the Casualty Department at King's College Hospital. Six months later, being now accepted as a "King's Man", he became an assistant surgeon in the Ear, Nose and Throat Department. Shortly afterwards, while practising for a mastoid operation on a cadaver, he was chiselling the bone when a bone chip flew into his right eye setting up an unpleasant infection. He was hospitalised, but the infection failed to settle and he was discovered to have diabetes. At his age at this time; this represented a death sentence.

Living with diabetes

[edit]Lawrence was initially controlled on a rigid diet and the eye infection settled, but was left permanently impaired vision in that eye. He abandoned the idea of a career in surgery and worked in the King's College Hospital Chemical Pathology Department under a Dr G. A. Harrison. Despite his gloomy prognosis and ill-health, he managed to conduct enough research to write his MD thesis.[5] A little later, in the expectation that he had only a short time to live, and not wishing to die at home causing upset to his family, he moved to Florence and set up in practice there. In the winter of 1922–23, his diabetes deteriorated badly after an attack of bronchitis and the end of his life seemed nigh.

In early-1922, Frederick Banting, Charles Best, James Collip and John Macleod in Toronto, Canada, made the discovery and isolation of insulin. Supplies were initially in short supply and slow to reach the UK, but in May 1923, Harrison cabled Lawrence – "I've got insulin – it works – come back quick". By this point, Lawrence was weak and disabled by peripheral neuritis and with great difficulty; drove across the continent and reached King's College Hospital on 28 May 1923. Following some preliminary tests, he received his first insulin injection on 31 May.[6][7][8] Lawrence's life was saved and he spent two months in hospital recovering and learning all about insulin. He was then appointed Chemical Pathologist at King's College Hospital and devoted the rest of his life to the care and welfare of people living with diabetes.

Diabetes physician

[edit]He developed one of the earliest and largest diabetes clinics in the country and in 1931 was appointed assistant physician-in-charge of the diabetes department at King's College Hospital, becoming full physician-in-charge in 1939. He also had a large private practice. He wrote profusely on his subject and his books The Diabetic Life and The Diabetic ABC did much to simplify treatment for doctors and patients. The Diabetic Life was first published in 1925 and became immensely popular, extending to 14 editions and translated into many languages. He published widely on all aspects of diabetes and its management, producing some 106 papers either alone or with colleagues, including important publications on the management of diabetic coma, on the treatment of diabetes and tuberculosis and on the care of pregnancy in diabetics.

In 1934, he conceived the idea of an association which would foster research and encourage education and welfare of patients. To this end a group of doctors and people with diabetes met in the London home of Lawrence's patient, H. G. Wells, the scientist and writer, and the Diabetic Association was formed. When other countries followed suit it became the British Diabetic Association (the BDA). Lawrence was Chairman of the Executive Council from 1934–1961 and Hon. Life President from 1962. His enthusiasm and drive ensured the life and steady growth of this association which soon became the voice of people with diabetes and constantly sought to promote their welfare. There are now active branches through the country. He was also a prime mover in production of "The Diabetic Journal" (forerunner of Balance), the first issue of which appeared in January 1935. Many articles thereafter were contributed by himself anonymously. He and colleague Joseph Hoet were the main proponents in founding the International Diabetes Federation and he served as their first president from 1950–1958. At their triennial conferences, Lawrence's appearance was always greeted with acclaim.

Almost immediately after his retirement, he suffered a stroke but his spirit remained indomitable and he continued seeing private patients to the end. His last publication was an account of how hypoglycaemia exaggerated the signs of his hemiparesis.[9] Although he preached strict control of diabetes for his patients, he did not keep to a strict diet himself taking instead supplementary shots of soluble insulin as he judged he needed them.[10]

Honours

[edit]Lawrence was Oliver-Sharpey lecturer at the Royal College of Physicians of London in 1946. His lecture was one of the earliest descriptions and detailed study of the rare condition now known as Lipoatrophic Diabetes.[11][12] He was recipient of the Banting Medal of the American Diabetes Association the same year; Banting Lecturer of the BDA in 1949 and in 1964 Toronto University conferred on him its LLD "honoris causa". Charles Best, then professor of physiology in Toronto, was probably the proposer for this honour as he had met and become friendly with Lawrence when doing postgraduate research in London with Sir Henry Dale and A. V. Hill in 1925–28. They remained lifelong friends meeting regularly when in each other's country.[13] Best was present at Lawrence's wedding to Doreen Nancy Batson on 7 September 1928.[14] The Lawrences had three sons.[15]

Death and legacy

[edit]

He died at home in London on 27 August 1968 aged 76.[15]

He is commemorated by an annual Lawrence lecture given by a young researcher in the field of diabetes to the Medical & Scientific Section of the BDA and by the Lawrence Medal awarded to patients who have been on insulin for 60 years or more.[16] The BDA, now Diabetes UK remains his lasting memorial.

References

[edit]- ^ Aberdeen Directories 1892–1919, Post Office

- ^ Aberdeen Grammar School Magazines 1900–1909

- ^ Roll of Graduates 1907–1925, Aberdeen University

- ^ Allardyce, M.D., ed. (1921), "Roll of Service in the Great War 1914–1919", Aberdeen University Studies No. 84, Aberdeen University Press, p. 253, retrieved 12 October 2013

- ^ Lawrence, RD (1922), The Estimation of Diastase in Blood and Urine and its Diagnostic Significance, MD Thesis, Aberdeen University

- ^ Lawrence, RD (1961). "Diabetes at King's". Kings College Hospital Gazette (40): 220–5.

- ^ "R.D. Lawrence Obituary". The Lancet. 292 (7567): 579. 1968. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(68)92449-5.

- ^ "R.D. Lawrence Obituary". BMJ. 3 (5618): 621–2. 1968. doi:10.1136/bmj.3.5618.621. PMC 1991182. PMID 4875647.

- ^ Lawrence. R D (1967). "Hemiplegia in a Diabetic Producing Unilateral Peripheral Neuritis and Hypoglycaemic Attack". The Lancet. 289 (7503): 1321–1322. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(67)91612-1. PMID 4165164.

- ^ Stowers, J.M. (1989), G P Milne (ed.), "Aberdeen: The History of Diabetic Research and Progress", Aberdeen Medico-Chirurgical Society: A Bicentennial History 1789–1989, Aberdeen University Press, pp. 212–26

- ^ Lawrence, R. D. (1946). "Lipodystrophy and hepatomegaly, with diabetes, lipaemia, and other metabolic disturbances; a case throwing new light on the action of insulin". Lancet. 1 (6403): 724 passim. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(46)90528-4. PMID 20982387.

- ^ Lawrence, R. D. (1946). "Lipodystrophy and hepatomegaly with diabetes, lipaemia, and other metabolic disturbances; a case throwing new light on the action of insulin. (concluded)". Lancet. 1 (6404): 773–775. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(46)91599-1. PMID 20986113.

- ^ Best, H M B (2003). Margaret and Charley: The Personal Story of Dr Charles Best, the Co- Discoverer of Insulin. Toronto, Canada: Dundurn Press. ISBN 1-55002-399-3.

- ^ Jackson, J.G.L. (1996). "R.D. Lawrence and the Founding of the Diabetic Association". Diabetic Medicine. 13 (1): 9–22. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199601)13:1<9::AID-DIA9>3.0.CO;2-P.

- ^ a b Pyke, David (2004). "Lawrence, Robert Daniel (1892–1968)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/56893. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ "RD Lawrence Lecture Award". Diabetes UK. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.