LGBTQ rights in Louisiana

LGBTQ rights in Louisiana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Status | Legal since 2003 (Lawrence v. Texas) |

| Gender identity | Altering sex on identity documents requires sex reassignment surgery |

| Discrimination protections | Protections in employment; some municipalities have passed further protections |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | Same-sex marriage since 2015 |

| Adoption | Full adoption rights since 2014 |

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Louisiana may face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Louisiana as a result of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Lawrence v. Texas. Same-sex marriage has been recognized in the state since June 2015 as a result of the Supreme Court's decision in Obergefell v. Hodges. New Orleans, the state's largest city, is regarded as a hotspot for the LGBTQ community.[1][2]

In September 2014, two courts, one federal and one state, produced contradictory rulings on the constitutionality of the state's denial of marriage rights to same-sex couples. The U.S. Supreme Court resolved that conflict when it ruled such bans unconstitutional in Obergefell v. Hodges on June 26, 2015. Two days later, Governor Bobby Jindal said the state would comply with that ruling and license same-sex marriages.

Discrimination on account of sexual orientation and gender identity is prohibited in employment as a result of Bostock v. Clayton County, but not in the areas of housing, health care, education, credit or public accommodations. A 2017 opinion poll from the Public Religion Research Institute showed that 63% of Louisiana residents supported anti-discrimination legislation protecting LGBTQ people.

Laws against same-sex sexual activity

[edit]There were no laws against same-sex sexual acts in Louisiana until 1805, when the Louisiana Territory enacted its first criminal code after annexation by the United States. The code contained a sodomy provision with the common-law definition and a mandatory penalty of life imprisonment at hard labor, whether heterosexual or homosexual.[3] In 1896, the state amended its sodomy statute, reducing the penalty to 2–10 years' imprisonment but the hard labor provision remained. It also extended the law's application to fellatio (oral sex). In the 1914 case of State v. Murry, the Louisiana Supreme Court held that the law included the "act called 'fellatio,' and perhaps that other perversion called 'cunnilingus', committed with the mouth and the female sexual organ". In 1942, a comprehensive criminal code revision was passed, reducing the maximum penalty for sodomy to five years' imprisonment, adding a fine of 2,000 dollars and making the hard labor provision optional.[3]

In one of only four court cases dealing with consensual lesbian activity in the country, in State v. Young et al. (1966), the Louisiana Supreme Court unanimously held that cunnilingus between lesbian partners was also criminal. In 1974, Louisiana adopted a constitutional provision dealing with the right to privacy, reading:[3]

Every person shall be secure in his person, property, communications, houses, papers, and effects against unreasonable searches, seizures, or invasions of privacy. No warrant shall issue without probable cause supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, the persons or things to be seized, and the lawful purpose or reason for the search. Any person adversely affected by a search or seizure conducted in violation of this Section shall have standing to raise its illegality in the appropriate court.

Despite the passage of the aforementioned provision, the state Supreme Court in State v. Lindsey (1975) ruled that the sodomy statute was not "unconstitutionally vague" nor a violation of privacy rights. That same year, the Louisiana State Legislature enacted a unique statute distinguishing between "homosexual rape" and "heterosexual rape", both punishable by death, though the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the death penalty for rape two years later in Coker v. Georgia. It also abolished the minimum penalty of two years' imprisonment (but kept the maximum penalty of five years), and inserted explicit language that sodomy could be committed with someone "of the same sex or opposite sex". Solicitation for sodomy, whether heterosexual or homosexual, was made a felony in 1982. In 1992, the state enacted a sex offender registration law, under which those convicted of consensual private sodomy would be registered as "sex offenders" on par with rapists and child abusers. The law required the offender to report any change of address and provide a photograph and fingerprints to the sheriff.[3]

The sodomy law was rendered unenforceable in 2003 by the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Lawrence v. Texas.[4] In 2005, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit struck down the part of the statute that criminalized adult consensual anal and oral sex.

In 2013, law enforcement officers in East Baton Rouge Parish arrested men who had engaged in sexual activity banned by the statute. The District Attorney did not prosecute those arrested, and both he and the parish sheriff supported repealing the sodomy statute. In April 2014, a bill to repeal the statute failed in the Louisiana House of Representatives on a 66–27 vote after lobbying in opposition by the Louisiana Family Forum, thus keeping an unconstitutional law on the books.[5][6]

In early May 2018, the Louisiana House of Representatives unanimously approved a bill toughening laws against bestiality and separating them from the unconstitutional sodomy law. The Senate passed the bill later that month in a 36–1 vote, and it was signed into law by Governor John Bel Edwards on May 25. Initially, ten Republican lawmakers stated their opposition to the anti-bestiality bill, which was also opposed by conservative groups, including the Louisiana Family Forum.[7][8]

Recognition of same-sex relationships

[edit]The U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges on June 26, 2015 held that the denial of marriage rights to same-sex couples is unconstitutional, invalidating the ban on same-sex marriage in Louisiana.

In 1988 and 1999, Louisiana added provisions to its Civil Code that prohibited same-sex couples from marrying and prohibited the recognition of same-sex marriages from other jurisdictions.[9][10] Louisiana added bans on same-sex marriage and civil unions to its Constitution in 2004.[11]

Two lawsuits challenged the state's bans. In state court in Costanza v. Caldwell, the plaintiffs won initially, but the ruling was stayed pending appeal, which was left unresolved after oral argument was heard on January 29, 2015.[12][13] In federal court in Robicheaux v. Caldwell, plaintiffs challenged the state's refusal to recognize same-sex marriages from other jurisdictions. U.S. District Judge Martin Feldman ruled on September 3, 2014 for the state, writing that "Louisiana has a legitimate interest ... whether obsolete in the opinion of some, or not, in the opinion of others ... in linking children to an intact family formed by their two biological parents".[14] On appeal to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, the case remained unresolved at the time of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Obergefell on June 26, 2015. Following the Supreme Court ruling, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals remanded the case back to the District Court, where Judge Feldman reversed his order, ruling in favor of the Robicheaux plaintiffs.

Adoption and parenting

[edit]Adoption by married couples

[edit]On September 22, 2014, Judge Edward Rubin found Louisiana's prohibition on allowing married same-sex couples to adopt to be unconstitutional and granted the first same-sex adoption in the state in Costanza v. Caldwell.[15] Prior to Judge Rubin's ruling, Louisiana allowed single persons to adopt and did not explicitly deny adoption or second-parent adoption to same-sex couples.[16] In light of the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, married same-sex couples are entitled to the same rights, benefits and responsibilities as married different-sex couples, including full joint adoption and parental rights.

Unmarried couples

[edit]In 2021, the Louisiana Supreme Court decided the case of Cook v. Sullivan. The court gave sole custody to a child's biological mother, ruling that another woman was not the parent, even though she had been in a relationship with the child's mother at the time of the birth and had acted as the second parent for years until she and the mother ended their relationship.[17]

Birth certificates

[edit]Louisiana has successfully defended in federal court its refusal to amend the birth certificate of a child born in Louisiana and adopted in New York by a married same-sex couple who sought to have a new certificate issued with their names as parents, as is standard practice for Louisiana-born children adopted by opposite-sex married couples.[18] On October 11, 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected a request from Lambda Legal, representing the plaintiffs in the case, Adar v. Smith, to review the case.[19] Louisiana birth certificates still use gender-specific terms when referring to parents; however, the Obergefell decision provides equal access to all marriage-related rights for same-sex spouses, reaffirmed by the court in Pavan v. Smith in June 2017. Preventing a married same-sex couple from being listed on their child's birth certificate is unconstitutional.[20][21] As of 2021, the only options for parents of a Louisiana birth certificate are "mother" and "father", with there being no options for same-sex couples, but Louisiana Vital Records will still list both same-sex parents despite this, although one of them will need to be misgendered on the child's birth certificate.

Fertility

[edit]Lesbian couples have access to fertility treatments and in vitro fertilization. State law recognizes the non-genetic, non-gestational mother as a legal parent to a child born via donor insemination, but only if the parents are married.[22]

Surrogacy is highly restricted in Louisiana. A bill passed in 2016 makes gestational surrogacy legal, but only for couples who are Louisiana residents and have both used their own gametes in the surrogacy process. Any individual or couple who needs a donor gamete (e.g., same-sex couples, infertile different-sex couples, or single individuals) cannot complete a surrogacy contract in the state. The surrogate mother cannot use her own egg.[23]

Discrimination protections

[edit]

On February 17, 1992, Governor Edwin Edwards issued an executive order prohibiting discrimination in state employment on the basis of sexual orientation.[24] In August 1996, Governor Murphy J. Foster, Jr. allowed the executive order to lapse. On December 4, 2004, Governor Kathleen Blanco reissued Edwards' executive order,[25] but in August 2008 Governor Bobby Jindal allowed it to expire.[26][27] On April 13, 2016, Governor John Bel Edwards reinstated the provision,[28] as announced shortly after his election.[29] However, Bel Edwards's order was struck down in November 2017 by an appellate court which found that the Governor had "overstepped his authority".[30] In March 2018, the Louisiana Supreme Court upheld the appellate court ruling.[31]

In May 2015, a House committee rejected a bill that would have protected people who exercise their religious beliefs on same-sex marriage. However, Governor Jindal then issued an executive order to that end.[32] On April 13, 2016, Governor Bel Edwards rescinded that executive order.

On April 28, 2016, the Senate Labor Committee approved in a 4–3 vote a bill that would have banned employment discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity.[33] The bill, however, did not advance any further and died at the end of the legislative term.

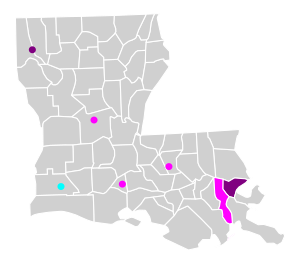

The cities of New Orleans,[34] and Shreveport[35][36] prohibit discrimination in employment, housing and public accommodations on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. Alexandria, Baton Rouge, Lafayette and Lake Charles along with the parish of Jefferson prohibit discrimination against public employees only.

Bostock v. Clayton County

[edit]On June 15, 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Bostock v. Clayton County, consolidated with Altitude Express, Inc. v. Zarda, and R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission that discrimination in the workplace on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity is discrimination on the basis of sex, and Title VII therefore protects LGBT employees from discrimination.[37][38][39]

Hate crime law

[edit]Louisiana is one of the few southern states which has a hate crime statute that provides penalty enhancements for crimes motivated by the victim's sexual orientation or perceived sexual orientation.[40] Passed in 1997, after a lobbying effort of five years, its passage made Louisiana the first state in the Deep South to have such a law.[41] The state law does not include gender identity, but hate crimes committed on the basis of the victim's gender identity can be prosecuted through federal courts under the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, which was signed into law in October 2009 by President Barack Obama.

Transgender rights

[edit]Transgender people are allowed to change the gender marker on their birth certificate and driver's license in Louisiana. The Office of Motor Vehicles requires applicants to submit a statement signed by a physician confirming that they have undergone successful sex reassignment surgery. The Louisiana Vital Records will issue a new birth certificate upon receipt of a certified copy of a court order confirming surgical gender change; "The court shall require such proof as it deems necessary to be convinced that the petitioner was properly diagnosed as a transsexual or pseudo-hermaphrodite, that sex reassignment or corrective surgery has been properly performed upon the petitioner, and that as a result of such surgery and subsequent medical treatment the anatomical structure of the sex of the petitioner has been changed to a sex other than which is stated on the original birth certificate of the petitioner".[42]

On June 5, 2023, the state Senate passed a bill to ban puberty blockers, hormones, and surgeries for minors. It is expected to pass the House too. Governor Edwards had not said whether he would veto it. If it became law, it would take effect January 1, 2024.[43] In June 2023, the Governor of Louisiana vetoed all the 3 bills.[44] In July 2023, the Legislature overridden the Governor veto - allowing just the bill on explicitly banning gender-affirming healthcare to minors to go into effect formally. The other 2 bills are awaiting action by the Legislature.[45]

Surgery, puberty blockers, hormone replacement therapy and other transition-related healthcare for transgender people are not covered by health insurance or state Medicaid policies.[22]

Transgender sports ban

[edit]In June 2022, Louisiana banned transgender girls from sports in public schools. The bill had more than two-thirds support in both chambers of the Louisiana State Legislature, so the governor, John Bel Edwards, did not try to veto it, as the legislators would have been able to override his veto.[46]

In 2021, a similar bill had passed (House vote 77–17 and Senate vote 29–6), but Governor Edwards vetoed it, calling it a dangerous "big-government overreach and discrimination". The legislature failed by just 2 votes to override his veto.[47][48][49][50][51]

Domestic violence law

[edit]In June 2017, the Louisiana Legislature passed a bill, introduced by Senator Patrick Connick, to remove the words "opposite-sex" from the domestic violence statutes. The bill, which passed 54–42 in the House and 25–13 in the Senate, was signed into law by Governor John Bel Edwards and went into full effect on August 1, 2017.[52] The bill's passage ensures that victims of domestic violence receive identical treatment irrespective of their sexual orientation; previously offenders in same-sex relationships received lesser sentences for domestic violence compared to their heterosexual counterparts. At that time, South Carolina was the only remaining state in the United States to still explicitly include the term "people of the opposite-sex" within its domestic violence laws.[53]

Freedom of expression

[edit]No promo homo law

[edit]The state of Louisiana maintains a so-called "no promo homo law" law, prohibiting sex education classes from discussing male or female homosexual activity.[54][55]

National Guard

[edit]Following the U.S. Supreme Court decision in United States v. Windsor in June 2013 invalidating Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act, the U.S. Department of Defense issued directives requiring state units of the National Guard to enroll the same-sex spouses of guard members in federal benefit programs. Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel on October 31 said he would insist on compliance.[56] On December 3, Louisiana agreed to conform with DoD policy stating that state workers would be considered federal workers while enrolling same-sex couples for benefits.[57]

Public opinion

[edit]Recent opinion polls have shown that support for LGBTQ people in the U.S. state of Louisiana is increasing significantly and opposition is decreasing.

A 2017 Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) poll found that 48% of Louisianans supported same-sex marriage, while 44% were opposed and 8% were undecided. Additionally, 61% supported an anti-discrimination law covering sexual orientation and gender identity. 29% were against. The PRRI also found that 54% were against allowing public businesses to refuse to serve LGBTQ people due to religious beliefs, while 37% supported such religiously-based refusals.[58]

A 2022 Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) poll found that 62% of Louisiana residents supported same-sex marriage, while 36% were opposed and 2% were unsure. The same poll found that 80% supported an anti-discrimination law covering sexual orientation and gender identity. 17% were opposed. Additionally, 61% were against allowing businesses to refuse to serve gay and lesbian people due to religious beliefs, while 38% supported such religiously-based refusals. [59]

| Poll source | Date(s) administered |

Sample size |

Margin of error |

% support | % opposition | % no opinion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Religion Research Institute | January 2-December 30, 2019 | 580 | ? | 63% | 27% | 10% |

| Public Religion Research Institute | January 3-December 30, 2018 | 692 | ? | 67% | 25% | 8% |

| Public Religion Research Institute | April 5-December 23, 2017 | 983 | ? | 61% | 29% | 10% |

| Public Religion Research Institute | April 29, 2015-January 7, 2016 | 1,170 | ? | 64% | 30% | 6% |

Summary table

[edit]| Right | Notes |

|---|---|

| Same-sex sexual activity legal | |

| Equal age of consent (17) | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in employment | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in housing | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in public accommodations | |

| Hate crime laws inclusive of sexual orientation and gender identity | |

| Same-sex marriages | |

| Stepchild and joint adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Lesbian, gay and bisexual people allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Transgender people allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Intersex people allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Right to change legal gender on birth certificate and driver's license | |

| Access to IVF for lesbian couples | |

| Gay and trans panic defense banned | |

| Conversion therapy banned on minors | |

| Third gender option | |

| Commercial surrogacy for gay male couples | |

| MSMs allowed to donate blood |

See also

[edit]- Politics of Louisiana

- LGBT rights in the United States

- Rights and responsibilities of marriages in the United States

References

[edit]- ^ "LGBT Travellers in New Orleans, USA". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on July 17, 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-17.

- ^ "New Orleans Gay History". www.neworleans.com. Archived from the original on July 17, 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-17.

- ^ a b c d "The History of Sodomy Laws in the United States - Louisiana". www.glapn.org.

- ^ New York Times: "Supreme Court Strikes Down Texas Law Banning Sodomy," June 26, 2003. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ Samuels, Diana (July 28, 2013). "East Baton Rouge Sheriff's Office plans to change practices, after report says deputies were ensnaring gay men". Times-Picayune. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ^ O'Donoghue, Julia (April 15, 2014). "Louisiana House votes 27-66 to keep unconstitutional anti-sodomy law on the books". Times-Picayune. Archived from the original on April 16, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ^ Simoneaux, Marie (31 May 2018). "John Bel Edwards signs tougher bestiality bill into law". NOLA.com.

- ^ 10 Louisiana Republicans voted to keep bestiality legal & anal sex against the law, LGBTQ Nation, April 11, 2018

- ^ "III. States Where Same-Sex Marriage is Prohibited". Fclaw.com. Archived from the original on 2014-04-16. Retrieved 2014-06-29.

- ^ La. C.C. arts. 89, 3520

- ^ "Forum for Equality PAC v. McKeithen". Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- ^ "Suspensive Appeal Motion and Order". Scribd.com. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ "Louisiana Supreme Court urged to rule in same-sex marriage". January 30, 2015. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- ^ Snow, Justin (September 3, 2014). "Federal judge finds Louisiana same-sex marriage ban constitutional". Metro Weekly. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ^ "Judge rules state's ban on same-sex marriage unconstitutional". The New Orleans Advocate. September 26, 2014. Archived from the original on July 12, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ Human Rights Campaign: Louisiana Adoption Law Archived 2011-05-24 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ Pavy, Lily (December 15, 2022). "Mommy Issues: Louisiana's Gap in Parental Rights for Unmarried, Same-Sex Couples". Louisiana Law Review. 83 (1): 320.

- ^ NOLA: "Gay dads lose appeal in Louisiana birth certificate case," April 12, 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ Bolcer, Julie (October 11, 2011). "Supreme Court Turns Down Adoption Birth Certificate Case". The Advocate. Retrieved June 28, 2015.

- ^ "Application for Certified Copy of Birth/Death Certificate" (PDF). Louisiana Department of Health.

- ^ "Louisiana LGBTQ Family Law" (PDF). familyequality.org. December 2017.

- ^ a b "Louisiana's equality profile". Movement Advancement Project.

- ^ a b "What You Need to Know About Surrogacy in Louisiana". American Surrogacy. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- ^ "La. Exec. Order No. EWE 92-7" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-20. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

- ^ "EXECUTIVE ORDER KBB04-54". www.doa.la.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-10-25. Retrieved 2019-08-28.

- ^ "Louisiana gov. drops gay anti-discrimination order". 365gay.com. Archived from the original on August 22, 2008. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ "Williams Institute" (PDF). 3Williams Institute. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 20, 2014. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ "Executive Order No. JBE 2016 - 11" (PDF). Governor of Louisiana. 13 April 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ^ "John Bel Edwards will issue executive order protecting LGBT state employees". NOLA.com. December 1, 2015. Archived from the original on December 2, 2015.

- ^ By, MARK BALLARD (November 2017). "Appeals court upholds ruling that Gov. Edwards overstepped with LGBT rights order". The Advocate.

- ^ "Louisiana Supreme Court Kills Order Protecting LGBT State Employees". www.advocate.com. March 25, 2018.

- ^ "Gov. Jindal Issues Order On Religious Freedom And Same-Sex Marriage". Buzzfeed. May 20, 2015.

- ^ "LGBT anti-discrimination employment bill advances in Senate". The Olympian. April 28, 2016.

- ^ "Cities and Counties with Non-Discrimination Ordinances that Include Gender Identity". Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- ^ McGaughy, Lauren (December 10, 2013). "Shreveport becomes second city in Louisiana after New Orleans to pass non-discrimination ordinance". The Times Picayune. Archived from the original on December 11, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ Campaign, Human Rights. "MEI 2014: See Your City's Score". Human Rights Campaign. Archived from the original on 2020-08-03. Retrieved 2019-08-28.

- ^ Biskupic, Joan (June 16, 2020). "Two conservative justices joined decision expanding LGBTQ rights". CNN.

- ^ "US Supreme Court backs protection for LGBT workers". BBC News. June 15, 2020.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (June 15, 2020). "Civil Rights Law Protects Gay and Transgender Workers, Supreme Court Rules". The New York Times.

- ^ Tully, Carol T. "Serving Diverse Constituencies: Applying the Ecological Perspectives". Accessed October 28, 2013.

- ^ "Hate Crimes Bill Out Of Committee With 'Sexual Orientation' Intact," May 1997 Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, Ambush Magazine, Accessed December 23, 2013.

- ^ "Louisiana". National Center for Transgender Equality.

- ^ Cline, Sara (5 June 2023). "Louisiana Senate passes bill banning gender-affirming care for transgender youths". ABC News. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ "Louisiana governor vetoes bills targeting gender-affirming care, pronoun usage". July 2023.

- ^ "BREAKING: Louisiana Legislators Override Governor's Veto of Extreme Gender Affirming Care Ban". 18 July 2023.

- ^ Golgowski, Nina (2022-06-08). "Louisiana Becomes Latest State To Ban Transgender Athletes In Schools". HuffPost. Retrieved 2022-06-08.

- ^ "Louisiana Republicans fail to override veto of bill barring transgender athletes from sports". 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Louisiana Won't Ban Transgender Athletes on Girls' Teams". NPR. 23 June 2021.

- ^ "Louisiana lawmakers send anti-trans sports ban to governor, who is likely to issue a veto | CNN Politics". CNN. 28 May 2021.

- ^ "Anti-Trans youth sports ban bill headed to Louisiana governor's desk". 28 May 2021.

- ^ "Louisiana State Legislature Sends Anti-Trans Sports Bill to Gov. John Bel Edwards' Desk". 27 May 2021.

- ^ "Bill Info - HB27". www.legis.la.gov.

- ^ Service, LSU Manship School News (16 March 2017). "Same-sex partners treated same as heterosexuals under Louisiana domestic violence bill". NOLA.com.

- ^ "State Anti-LGBT Curriculum Laws". Lambda Legal.

- ^ "La. R.S. § 17:281". www.legis.la.gov.

- ^ Johnson, Chris (October 31, 2013). "Hagel to direct nat'l guards to offer same-sex benefits". Washington Blade. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ Johnson, Chris (December 3, 2013). "Louisiana Nat'l Guard latest to process same-sex benefits". Washington Blade. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ "PRRI – American Values Atlas". ava.prri.org.

- ^ "PRRI – American Values Atlas". ava.prri.org.

- ^ Baldor, Lolita; Miller, Zeke (January 25, 2021). "Biden reverses Trump ban on transgender people in military". Associated Press.

- ^ "Medical Conditions That Can Keep You From Joining the Military". Military.com. 25 February 2022.

- ^ McNamara, Audrey (April 2, 2020). "FDA eases blood donation requirements for gay men amid "urgent" shortage". CBS News.