Saba (island)

Saba | |

|---|---|

Satellite image of Saba | |

| Motto(s): | |

| Anthem: "Saba you rise from the ocean" | |

Location of Saba (island) (circled in red) in the Caribbean | |

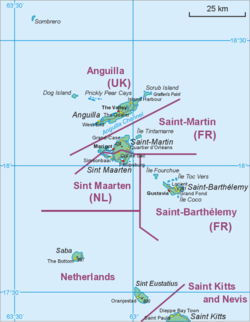

Map showing location of Saba relative to Sint Eustatius and Saint Martin. | |

| Coordinates: 17°37′57″N 63°14′15″W / 17.63250°N 63.23750°W | |

| Country | |

| Overseas region | Caribbean Netherlands |

| Incorporated into the Netherlands | 10 October 2010 (dissolution of the Netherlands Antilles) |

| Capital (and largest city) | The Bottom |

| Government | |

| • Lt. Governor | Jonathan Johnson |

| Area | |

| • Total | 13 km2 (5 sq mi) |

| Population (1 January 2022)[2] | |

| • Total | 1,911 |

| • Density | 148/km2 (380/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Saban |

| Languages | |

| • Official | English[3] • Dutch |

| Ethnicity | |

| • Saban | 26.6 % |

| • Sint Maarten | 15.7 % |

| • American | 10.0 % |

| • other | 47.7 % |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (AST) |

| Calling code | +599-4 |

| ISO 3166 code | BQ-SA, NL-BQ2 |

| Currency | United States dollar ($) (USD) |

| Internet TLD | |

Saba (/ˈseɪbə/ SAY-bə,[6] Dutch: [ˈsaːbaː] )[7] is a Caribbean island and the smallest special municipality (officially "public body") of the Netherlands.[8][9] It consists largely of the dormant volcano[10] Mount Scenery, which at 887 metres (2,910 ft) is the highest point of the entire Kingdom of the Netherlands. The island lies in the northern Leeward Islands portion of the West Indies, southeast of the Virgin Islands. Together with Bonaire and Sint Eustatius it forms the BES islands, also known as the Caribbean Netherlands.

Saba has a land area of 13 square kilometres (5.0 sq mi).[1] The population was 1,911 in January 2022,[11] with a population density of 147 inhabitants per square kilometre (380/sq mi). It is the smallest territory by permanent population in the Americas. Its towns and major settlements are The Bottom (the capital), Windwardside, Zion's Hill, and St. Johns.

Etymology

[edit]Theories about the origin of Saba's name include siba (the Arawakan word for 'rock'), sabot, sábado, and Sheba.[12][13] The island was referred to by its present name, Saba, as early as 1595 when it appeared in a voyage account by John Hawkins.[13] Before its present name, the island was designated "St. Christopher" (San Cristóbal)[14] by Christopher Columbus.[13]

History

[edit]

Saba is thought to have been inhabited by the Ciboney people as early as the 1100s BC.[15] Later, circa 800 AD, Arawak people from South America settled on the island.[15]

Christopher Columbus is said to have sighted the island on 13 November 1493, however, he did not land, being deterred by the island's perilous rocky shores.[15] In 1632, a group of shipwrecked Englishmen landed upon Saba.[15] In the 1640s, the Dutch governor of the neighbouring island of Sint Eustatius sent several Dutch families over to colonise the island for the Dutch West India Company.[15] In 1664, refusing to swear allegiance to the English crown, these original Dutch settlers were evicted to St. Maarten by Jamaican governors pirates Edward, Thomas, and Henry Morgan.[15][16] The Netherlands eventually gained complete control of the island in 1816.[15]

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Saba's major industries were sugar, indigo, and rum produced on plantations owned by Dutchmen living on St. Eustatius, and later fishing, particularly lobster fishing.[citation needed] To work these plantations, enslaved people were imported from Africa.[15] In the 17th century, Saba was believed to be a favourite hideout for Jamaican pirates.[15] England also deported its "undesirable" people to live in the Caribbean colonies, and some of them also became pirates, a few taking haven on Saba.[17] As the island's coast is forbidding and steep, the island became a private sanctuary for the families of smugglers and pirates. One notable Saban pirate was Hiram Beakes, son of the Dutch councillor of the island.[18]

In August 1857[19] Venezuela and The Netherlands submitted a dispute over the possession of Isla de Aves to arbitration by the Queen of Spain,[19] because the Netherlands considered the island linked to its colony of Saba by a sand bank,[19] and fishermen from St. Eustatius and Saba had used the place to harvest turtles and birds' eggs,[20] while Venezuela argued that it had inherited the island from Spain which had discovered all the Caribbean islands,[20] that the fishermen were not acting on behalf of any government but for a particular interest[20] and that this island was not attached to the territory that the Netherlands had received.

The Spanish decision[21] of June 30, 1865,[22] declared that the ownership of the Island belonged to Venezuela[22] and that the Netherlands should nevertheless be compensated.[19] It argued that even if the two islands had been united, the sandbank was now separate from the island of Saba and that the first state to have a military force[23] and to exercise sovereignty there[23] had been Venezuela, which had inherited it from the Captaincy General of Venezuela.[23]

During that time,[when?] Saba lace, a Spanish form of needlework introduced by a nun from Venezuela, became an important product made by the island's women.[15] Throughout the late 19th century and early 20th century, the primary source of revenue for the island came from the lacework produced by these women. During this period of time, with most of the island's men gone out to sea for extended periods, the island became known as "The Island of Women".[24][15]

In 1943, Joseph "Lambee" Hassell, a self-taught engineer, began building a road on Saba, drastically improving transport on the island, which had been carried out only by foot or by mule previously.[15] An airport followed in 1963, and a larger pier geared for tourist boats in 1972.[15] As a result, tourism increased, gradually becoming a major part of the Saban economy.[15]

In 1978, Venezuela[25][26] and the Kingdom of the Netherlands[25] signed the maritime limits treaty[27] that defined the extension of the Dutch and Venezuelan exclusive economic zone in two areas, the first between the islands of Aruba,[28] Curaçao, and Bonaire (in front of the State of Falcon in Venezuela and next to the Los Monjes Archipelago)[29] and a second area further north that includes the islands of Saba[30] and St. Eustatius,[30] the latter taking as a reference the Isla de Aves[15] (the northernmost point of Venezuela in the Caribbean Sea). At that time, the six islands were part of an administrative entity called the Netherlands Antilles. The treaty recognizes an equidistant or median line[31] between the Island of Aves and the Island of Saba as a maritime boundary.[32]

A status referendum was held in Saba on 5 November 2004,[33] and 86.05% of the population voted for closer links to the Netherlands. This was duly achieved in October 2010, when the Netherlands Antilles was dissolved and Saba became a special municipality of the Netherlands.[15]

Geography and ecology

[edit]

Saba is a small island at 13 square kilometres (5.0 sq mi) in size and roughly circular in shape.[34] It lies north-west of Sint Eustatius and south-west of Saint Barthélemy and Sint Maarten. The terrain is generally mountainous, culminating in Mount Scenery volcano in the island's centre.[34] Off the north coast lies the much smaller Green Island.

Saba is the northernmost active volcano in the Lesser Antilles Volcanic Arc chain of islands. At 887 metres (2,910 ft), Mount Scenery is also the highest point within the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The island is composed of a single rhombus-shaped volcano measuring 4.6 kilometres (2.9 mi) east to west and 4.0 kilometres (2.5 mi) north to south[35] The oldest dated rocks on Saba are around 400,000 years old, and the most recent eruption was shortly before the 1630s European settlement (280 years B.P.).[35][36] Between 1995 and 1997, an increase in local seismic activity was associated with a 7–12 °C (45–54 °F) rise in the temperature of the hot springs on the island's northwest and southeast coasts.[35]

There is an 8.6 hectares (21 acres)[37] cloud forest located at and above 825 metres (2,707 ft)[38] on top of the mountain referred to as the "Elfin Forest Reserve" because of its high altitude mist and mossy appearance.[37] The most dominant tree in the cloud forest is the Mountain Mahogany (Freziera undulate), although hurricanes over the years have destroyed a large number of the mature trees. Despite the name, the mountain mahogany is not related to other mahogany species; although one species of true mahogany tree is found on the island at lower levels, the small-leaved mahogany (Swietenia mahagoni). In the underbrush of the mahogany trees, the Sierran palm (Prestoea montana) and tree ferns dominate, with a large variety of epiphytes and Orchids growing on the trunks and branches of all the trees.[38] Wild raspberries and plantain trees can also be found growing on most of the mountain.[39] All seven of the Lesser Antilles Endemic Bird Area restricted-range birds occur in the Elfin Forest Reserve.[38]

Below the cloud forest is a sub-montane forest, and the variety and average number of species are considerably less. Redwood and Mountain fuchsia tree trees grow wild in this zone, as well as cactus species such as the prickly pear, and Seagrape trees. On the lowest southern and eastern slopes of Saba are grassy meadows and scattered shrubs.[39] Saba National Land Park is a 35 hectares (86 acres) national park located on the north coast of Saba.[40] Formerly owned by the Sulphur Mining Company, the park was established in January 1998 and the property was officially turned over to the Saba Conservation Foundation in 1999.[37] It stretches from the coastline all the way up to the cloud forest, and encompasses all vegetation zones present on Saba.

The coastline of Saba is mostly rubble and rocky cliffs that are 100 metres (330 ft) or taller with mostly cobble and boulder permanent beaches.[10] The steep terrain and sheer bluffs dropping almost straight down to the ocean's edge prevents the formation of mangrove swamps or much vegetation. There are eight bays tucked into the cliffs around the island; Cove Bay, Spring Bay, Core Gut Bay, Fort Bay (location of the island's only port), Tent Bay, Ladder Bay, Wells Bay and Cave of Rum Bay.[38] Saba's coastline also includes the Flat Point Tide Pools, which were created by a large lava flow thousands of years ago. These tide pools are located below the airport at Flat Point, and feature large lava rock formations filled with colorful saltwater pools.[41] The pools are home to diverse marine life,[41] including small fish, sea urchins, crabs, and sea flora.[42][43][44]

The shoreline of the island is of particular value to sea birds, and has been designated an Important Bird Area (IBA AN006 – "Saba Coastline") by BirdLife International.[45] Saba is home to about sixty species of birds, many of which are sea birds that use the holes and crevices of the steep cliffs and two small islands for breeding and feed in the waters around the island.[39] Saba's shoreline is home to the Caribbean's largest breeding colony of Red-billed tropicbird (Phaethon aethereus).[38] Other birds include the Common Ground Dove, the Brown Noddy, the Least Sandpiper, and the Yellow-billed Tropicbird.[46] The Audubon's Shearwater (Puffinus lherminieri) is another common bird, and is the national bird of Saba as well as being featured on their coat of arms.[45]

Being an island, Saba is home to a number of endemic species including the Saban black iguana (Iguana iguana melanoderma), Red-bellied racer (Alsophis rufiventris), Saban anole (Anolis sabanus), and Lesser Antillean funnel-eared bat (Natalus stramineus stramineus).[45][39] However, several non-native species have settled on the island, including the Underwood's spectacled tegu (Gymnophthalmus underwoodi), brahminy blind snake (Indotyphlops braminus), and non-native iguanas, all of which are believed to have arrived on cargo shipments from St. Maarten.[47][48][49]

About 4.3 kilometres (2.7 mi) southwest of the island is the northeastern edge of the Saba Bank, the largest submarine atoll in the Atlantic Ocean[50] with an especially rich biodiversity. Saba Bank is the top of a sea mount and it is a prime fishing ground, particularly for lobster.

Government

[edit]

Relationship with mainland Netherlands

[edit]Saba became a special municipality within the country of the Netherlands after the dissolution of the Netherlands Antilles on 10 October 2010 and is not part of a Dutch province. The island's constitutional status, as well as those of Sint Eustatius and Bonaire, is set out in the Law on the Public Entities BES (Dutch: Wet op de Openbare Lichamen BES).[51]

Sabans vote for members of the Dutch House of Representatives, the members of which are elected on a party-list proportional method.[52] During the 2017 Dutch general election, a majority of Sabans voted for Democrats 66. Of the island's 2,000 residents, 900 were eligible to vote, and of those, 42.8% (or 385 people) voted.[53]

Sabans with Dutch nationality are allowed to vote in elections for the Electoral College to elect the members of the Dutch Senate. The 2019 elections on Saba, held concurrently with the 2019 Island Council Elections resulted in four of the five Saban seats in the Electoral College going to the Windward Islands People's Movement and one seat going to the Saba Labour Party.[54]

Governor

[edit]The island governor is the head of the government of Saba. The Dutch monarch appoints the governor for a term of six years, and he or she falls under the supervision of the minister of the interior and kingdom relations. The island governor chairs meetings of both the Island Council and the Executive Council.[52]

They are also responsible for representing the island's government both in and out of court, maintaining public order, implementing policy and legislation, coordinating with other governments, and receiving and handling complaints about the island's government.[55]

The incumbent island governor is Jonathan G. A. Johnson.[52]

Legislature

[edit]Saba's legislative body is the Island Council, of which there are five members. Councillors are elected by the citizens of the island every four years.[56] The Island Council holds the power to:[57]

- Appoint and remove commissioners of the Executive Council.

- Pass ordinances to be enforced by the Executive Council.

- Ask questions of the Executive Council.

- Begin an investigation into the governor or the Executive Council.

- Approve the budget.

Following the 2023 island elections, the Windward Islands People's Movement (WIPM) holds three seats on the Island Council, while the new Party for Progress, Equality, and Prosperity held two.[58] In 2019, Esmeralda Johnson was the youngest person ever to be elected to the council.[59]

Members of the Island Council are:

| Name | Party |

|---|---|

| Saskia Matthew | PEP |

| Julio Every | PEP |

| Rolando Wilson | WIPM |

| Elsa Peterson | WIPM |

| Vito Charles | WIPM |

Executive

[edit]The Executive Council, appointed by the Island Council, acts as the executive branch of government. The council has the following responsibilities:[62][63]

- Day-to-day administration of the island, except for duties reserved for the Island Council or the governor.

- Executing policies and legislation passed by the Island Council.

- Establishing rules regarding the administration of the island, except the Registry.

- Appointing, promoting, suspending, or dismissing public officials, except those working for and including the registrar.

- Preparing defence of the island.

- Maintaining contact with Dutch ministries in the Hague.

- Executing policies and legislation from the national government.

The council appoints the island secretary, currently Tim Muller.[64]

The council consists of the island governor and two commissioners appointed by the Island Council, currently both members of the WIPM.[63] Each member of the Executive Council is assigned portfolios to oversee.[65]

| Name | Title | Party | Portfolios[66] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jonathan Johnson | Governor | N/A | Census (Civil Status, Registry, & Elections), Personnel Affairs & Organization, Disaster Management, Protocol, Public Safety, Communication, Digitalization & Information Technology |

| Rolando Wilson | Commissioner | WIPM | General Affairs, Finances & Economic Affairs, Agriculture, Husbandry & Fisheries, Planning & Infrastructure, Energy, Public Works, Constitutional Affairs, Tourism, Water Supply, Harbor, Airport, Nature & Environment, Sanitation & Waste Management |

| Evolution Heyliger | Commissioner | WIPM | Education, Community Development, Social & Labor Affairs, Social Housing, Health & Hygiene, Culture & Sports, Archives, Youth Affairs, Gender Affairs, Cadastre, European Union funds, Telecommunications |

Society

[edit]

The population of Saba (the Sabans) was 2,010 in 2017.[67] Saba's small size has led to a fairly small number of island families, who can trace their last names back to around a half-dozen families. This means that many last names are shared across the island, the most numerous being Hassell, Johnson and Every; these three names are shared by upwards of 30% of Saba's population.[68]

Most families' ancestry is a result of the intermixing of Africans, Dutch, English, and Scottish. The population is also partly descended from the Irish who were exiled from that country after the accession of King Charles I of England, Scotland and Ireland in 1625. Charles exiled these Irish to the Caribbean in an effort to quell a rebellion after he had forcibly procured their lands for his Scottish noble supporters.[citation needed]

Historically, Saba was traded among the many European nations that fought for power in the region. Slaves from Africa were also imported to work on Saba. In recent years Saba has become home to a large group of expatriates, and around 250 immigrants who are either students or teachers at the Saba University School of Medicine.[69]

Languages

[edit]Both English and Dutch are spoken on the island and taught in schools, and both languages are official. Despite the island's Dutch affiliation, English is the principal language spoken on the island and has been used in its school system since the 19th century. Dutch is spoken by 34% of the population, while English is spoken by over 96% of the population.[70]

The majority (67%)[70] of Sabans speak more than one language, including English, Dutch, Spanish, Papiamento, and many others.[70]

| Year | Dutch | English | Papiamento | Spanish | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 32.3% | 99.6% | 13.4% | 27.1% | 23.3% |

| 2017/2018 | 34.0% | 96.9% | 10.7% | 32.6% | 25.7% |

English is the medium of instruction in Saba schools. Dutch government policy towards Saba and other SSS islands promotes English-medium education.[71] English can therefore be used in communications of and to the government.

Saban English is the local English vernacular spoken on the island. It has previously been described as a decreolized variety of Virgin Islands Creole English.[72] The first dictionary of Saban English was published in 2016.[73][74]

Religion

[edit]

Saba has a predominantly Christian population. The main denominations are Catholicism (45%), Non-denominational Christianity (18%), Anglicanism (9%), Evangelicalism (4%), and Pentecostalism 4%, with an additional 11% adhering to other Christian denominations. In addition, 6% of the population is Muslim.[75]

The first contact with Christians on the island occurred with the visit of Christopher Columbus in 1493, but this did not mean the immediate arrival of the Catholic Church. It is believed that the first Christian groups to settle on the island were Protestants coming from the Netherlands in 1640.[76]

During the period of nominal Spanish domination, the island was included in the jurisdiction of the Diocese of Puerto Rico

The oldest church on record is the Christuskerk (Christ Church),[77] of the Anglican denomination, which was renovated in 1777 after being damaged by a hurricane, and whose exact date of construction is unknown. In the same year, Pastor Kirkpatrick also requested permission from the Dutch commander Johannes de Graaff to officially establish the Anglican Church in Saba[78] before that some locals used the Reformed Church of the Netherlands to celebrate their baptisms.[79]

Although the Roman Catholic Church is currently very active on Saba, it did not establish itself on the island until quite late.[80] One of the earliest contacts includes the visit of Père Labat in 1701.[80]

The island was also visited by the Prefect Apostolic of the Catholic Church for the Dutch Colonies in the Caribbean in 1836[79] Monsignor Martinus Niewindt, according to his report there was no Catholic priest to attend the island at that time. He returned in May of the same year with the Venezuelan priest Manuel Romero[79] who had settled in Curaçao 1 year earlier for political reasons.[79] Communication was difficult at first because neither of the two priests spoke English, Romero spoke only Spanish and Niewindt spoke only French and Dutch. In June 1836, the first Catholic mass on the island was officially celebrated in Saba, and five children were presented for baptism.[79]

The oldest Catholic Church on record and still functioning today is St. Paul's Conversion Church in Windward, which dates back to 1860.[79]

Missionary activity, the arrival of immigrants from other parts of the Netherlands and other territories in the Caribbean and Europe made the Catholic Church the most popular denomination in the present day, as it represents nearly half of the population.[75]

Health and healthcare

[edit]The A.M. Edwards Medical Center is the major provider of healthcare for local residents.[81] The center was built in 1980 and renovated in 2019.[81][82] Home healthcare is available for Sabans who require medical care in their own home.[83] Saba also has an assisted living facility located in the H.C. Every building.[83]

Saba has a hyperbaric chamber located at Fort Bay Harbor,[84] as scuba diving is a popular tourist activity on Saba.[85]

Same-sex marriage

[edit]In Saba (as in Bonaire and Sint Eustatius), marriage is open to same sex and opposite sex couples[86] following the entering in force of a law enabling same-sex couples to marry on 10 October 2012.[87] The first same-sex marriage was performed on Saba on 4 December 2012 between a Dutch man and a Venezuelan man, both residing in Aruba, where same-sex marriage is not performed.[88][89][90]

Economy

[edit]Since 2011, the U.S. dollar has been the official currency,[91] replacing the Netherlands Antillean guilder.

Agriculture

[edit]Agriculture on Saba is primarily livestock and vegetables, especially potatoes. Saba lace, also known as "Spanish work", is actually drawn thread work and is still produced on the island.

Tourism

[edit]

The tourism industry now contributes more to the island's economy than any other sector. There are about 15,000 visitors each year. Saba has a number of inns, hotels, rental cottages and restaurants. Saba is known as the "Unspoiled Queen" of the Caribbean.[92] Saba is especially known for its ecotourism, having exceptional scuba diving, climbing and hiking.

The Juancho E. Yrausquin Airport offers flights to and from the nearby islands of St. Maarten and Sint Eustatius. There is also a ferry service from St. Maarten; the ferry boats "Dawn II ~ The Saba Ferry" and "The Edge" both travel to Saba three times a week. In addition, there are anchorages for private boats.[92]

About 150 species of fish have been found in Saba's waters.[93] A main draw for divers are the pinnacle dive sites, where magma pushed through the sea floor to create underwater towers of volcanic rock that start at about 300 feet (91 m) down and rise to about 85 feet (26 m) beneath the surface.[93] The waters around Saba were designated as the Saba National Marine Park in 1987, and are subject to government regulation to preserve the coral reefs and other marine life. Since 1991 the Saba Conservation Foundation has operated a hyperbaric chamber in case of diving emergencies.[94]

Transport

[edit]

There is one main road, known as "The Road". Its construction was masterminded by Josephus Lambert Hassell who, contrary to the opinion of Dutch and Swiss engineers, believed that a road could be built.[95] He took a correspondence course in civil engineering and started building the road with a crew of locals in 1938.[96] In 1943, the first section of the road from Fort Bay to The Bottom was completed. In 1947, the first motor vehicle arrived. In 1951, the road to Windwardside and St. Johns was opened. In 1958, the road was completed.[96]

Driving "The Road" is considered to be a daunting task, and the curves in Windwardside are extremely difficult to negotiate. Driving is on the right hand side. The speed limit in towns is 20 kilometres per hour (12 mph), and outside of towns, is 40 kilometres per hour (25 mph).

In 1963, [citation needed] Saba residents built the Juancho E. Yrausquin Airport. This 400-metre (1,300 ft) landing strip is reputed to be the shortest commercial runway in the world,[97] and is restricted. Only trained pilots flying small STOL airliners, such as the Twin Otter and the Britten-Norman Islander, may land there, as well as helicopters.

In 1972, a pier was completed in Fort Bay to access the island. Travel is also provided by ferry services to and from Sint Maarten with the Makana and The Edge ferries.

Of note are 800 steps carved from stone, known as "The Ladder",[98] which reach from Ladder Bay to the settlement known as The Bottom. Until the late 20th century, everything that was brought to the island in boats and ships was carried up by hand using these steps. The steps are now often used by tourists who wish to experience an intense climb.

Energy

[edit]Like many Caribbean islands, Saba is dependent on fossil fuels imports, which leaves it vulnerable to global oil price fluctuations that directly affect the cost of electricity.[99] Electricity supply depends on a diesel power plant to supply 60% of the island's demand.[100] In 2019, solar parks in Hell's Gate (adjacent to the airport) and The Bottom became operational. For up to 10 hours a day, the entire island of Saba is powered by solar energy from these two solar parks and their battery storage.[101][102][103]

According to a report by the Low Emission Development Strategies Global Partnership (LEDS GP), the Government of Saba made the decision to transform the island to 100% sustainable energy to eventually eliminate dependence on fossil fuel-generated electricity. This new energy policy is defined by the 'Social development plan 2014–2020' and 'Saba's energy sector strategy'. Intermediate targets are 20% renewable electricity by 2017, which was reached in 2018; and 40% by 2020, which is expected to be reached by March 2019.[100][needs update]

Education

[edit]The primary school is Sacred Heart Primary School in St. John's.[104] There is also one secondary and vocational school in Saba, the Saba Comprehensive School in St. John's.[105]

Saba University School of Medicine is a for-profit medical school located in The Bottom, Saba's capital. The medical school was established by American expatriates in coordination with the government of the Netherlands.[106] The school adds over 400 residents when classes are in session,[106] and it is the prime educational attraction.

Culture

[edit]The lifestyle on Saba is generally slow with little nightlife, even with the emergence of an ecotourism industry in the last few decades. Sabans are proud of their history of environmental conservation, calling Saba "The Unspoiled Queen".[92]

Saban women continue to make two traditional island products, Saba Lace and Saba Spice. Saba Lace is hand-stitched lace, which the island's women began making in the late 19th century and built into a thriving mail-order business with the United States. Saba Spice is a rum drink, brewed with a combination of spices.

As in other Caribbean locations, Sabans throw an annual Carnival. Saba's Carnival takes place the last week in July and includes parades, steel bands, competitions, and food.

Another event held in the capital The Bottom is 'Saba Day'. This is the national day of the island in which all offices, schools and stores are closed. The island celebrates its diversity and culture through various activities and parades. The Bottom holds host to a concert at the sports field where local and other Caribbean artists come to perform. A wahoo fishing tournament is also held during Saba Day and attracts boats from neighboring islands such as St. Maarten, St. Eustatius, and St. Barths.

Media

[edit]There is one radio station on Saba, "Saba Radio" broadcasts on 93.9 FM and 1410 AM.[107][108]

There is one online newspaper in Saba, Saba News, which publishes local news as well as pieces from the rest of the Dutch Caribbean.[109]

Museums

[edit]The Harry L. Johnson Museum in Windwardside features exhibits that include collections from the 19th and early 20th centuries,[110] including period photographs of Dutch royalty, antique furniture, a 100-year old organ harmonium, and a stone hearth, as well as objects from archaeological sites of the island's first inhabitants.[111]

The Bottom's Major Osman Ralph Simmons Museum, founded by Major Osmar Ralph Simmons, a former island police officer for more than 40 years, preserves and displays objects he found on the island.[112]

Sports

[edit]The most popular sports on Saba are football, futsal,[113][114] softball,[115] basketball, and volleyball. The Saba Volleyball Association is a member of ECVA and NORCECA.[116]

Notable Sabans

[edit]- Cornelia Jones, innkeeper and politician

- Barbara Kassab-Every, Saba-born landscape painter

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Zaken, Ministerie van Algemene (May 19, 2015). "Waaruit bestaat het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden? – Rijksoverheid.nl". onderwerpen (in Dutch). Retrieved Oct 4, 2021.

- ^ "Caribisch Nederland; bevolking; geslacht, leeftijd, burgerlijke staat". CBS StatLine. 2022-04-28. Retrieved 2022-08-14.

- ^ English can be used in relations with the government. "Invoeringswet openbare lichamen Bonaire, Sint Eustatius en Saba" (in Dutch). wetten.nl. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ "BQ – Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba". ISO. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ "Delegation Record for .BQ". IANA. 20 December 2010. Archived from the original on 29 May 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). "Saba island in the Caribbean". Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

some reference books wrongly claim it is ˈsɑːb ə or ˈsæb ə

- ^ Mangold, Max (2015). "Duden – Das Aussprachewörterbuch". Der Duden in zwölf Bänden. Institut für Deutsche Sprache. p. 747.

- ^ "Wet openbare lichamen Bonaire, Sint Eustatius en Saba

(Law on the public bodies of Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba)". Dutch Government (in Dutch). Retrieved 14 October 2010. - ^ "31.954, Wet openbare lichamen Bonaire, Sint Eustatius en Saba" (in Dutch). Eerste kamer der Staten-Generaal. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

De openbare lichamen vallen rechtstreeks onder het Rijk omdat zij geen deel uitmaken van een provincie. (The public bodies (...), because they are not part of a Province)

- ^ a b Rahn, Jennifer L. (2017), Allen, Casey D. (ed.), "Saba and St. Eustatius (Statia)", Landscapes and Landforms of the Lesser Antilles, World Geomorphological Landscapes, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 61–84, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-55787-8_6, ISBN 978-3-319-55785-4, retrieved 2022-07-11

- ^ "The Caribbean Netherlands in Numbers 2022: How has the population evolved over the past decade?". cbs.nl. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. Archived from the original on 2023-02-06.

- ^ Myrick, Caroline (2014). "Putting Saban English on the map". English World-Wide. A Journal of Varieties of English. 35 (2): 161–192. doi:10.1075/eww.35.2.02myr. Retrieved 2022-06-28.

- ^ a b c Hartog, Johan (1988). History of Saba. Saba: Saba Artisan Foundation.

- ^ Hidrografía, Spain Dirección de (1826). Derrotero de las islas Antillas, de las costas de Tierra Firme, y de las del seno Megicano (in Spanish). En la Imprenta Nacional.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Saba Government- History of Saba". Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ Johnson, Will (2014-12-18). "Driving out the Dutch". The Saba Islander. The Saba Herald. Retrieved 2019-03-11.

Sir Henry Morgan, famous pirate, and Governor of Jamaica. His two uncles, Edward (also his father-in-law) and Thomas, captured St. Eustatius and Saba in 1665 and drove out the Dutch. …

- ^ "General info". Statia and Saba Chamber of Commerce & Industry. Archived from the original on 2014-03-08. Retrieved 2020-08-25.

- ^ Gelt Dekker, Jacob (30 January 2018). "Hiram Beakes of Saba". StMaartenNews. Retrieved 2019-07-25.

- ^ a b c d United States Congressional Serial Set. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1895.

- ^ a b c Fontaine, Henri La (1997-09-24). Pasicrisie Internationale 1794-1900: Histoire Documentaire Des Arbitrages Internationaux. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-90-411-0454-0.

- ^ Barandiarán, Daniel de (1989). El laudo español de 1865 sobre la Isla de Aves (in Spanish). Universidad Católica del Táchira.

- ^ a b Vázquez, Honorato (1892). Memoria historico-jurídica sobre los límites ecuatoriano-peruanos (in Spanish). Imprenta del Clero.

- ^ a b c Seijas, Rafael Fernando (1884). El derecho internacional hispano-americano (público y privado) (in Spanish). "El Monitor.

- ^ "Preserving Tradition on the Island of Women and Lace". Brigham Young University. 2015-09-21. Archived from the original on 2016-01-08. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- ^ a b Prescott, Victor; Schofield, Clive (2005-01-01). The Maritime Political Boundaries of the World: 2nd edition. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-474-0620-4.

- ^ Dromgoole, Sarah (2006). The Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage: National Perspectives in the Light of the UNESCO Convention 2001. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-15273-1.

- ^ Paúl, Isidro Morales (1983). La delimitación de áreas marinas y sub-marinas al norte de Venezuela (in Spanish). Academia de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales.

- ^ Wells, Jeffrey V.; Wells, Allison Childs; Dean, Robert (2017-06-15). Birds of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curacao: A Site and Field Guide. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-1286-9.

- ^ Días, Alberto J. Rodríguez (1995). Cuentanos de nuestras fronteras: fronteras de Venezuela (in Spanish). SUELOPETROL. ISBN 978-980-07-2927-4.

- ^ a b Charney, Jonathan I.; Colson, David A.; Alexander, Lewis M.; Smith, Robert W. (1993). International Maritime Boundaries. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-14461-3.

- ^ Lagoni, Rainer; Vignes, Daniel (2006-06-01). Maritime Delimitation. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-474-1834-4.

- ^ Bölükbasi, Deniz (2012-12-06). Turkey and Greece: The Aegean Disputes. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-32852-8.

- ^ Saba Tourist Bureau. "Referendum on the Constitutional Future of Saba 2004". Archived from the original on 2006-12-30. Retrieved 2007-02-02.

- ^ a b "Saba". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ a b c "The Geology of Saba". Caribbean Volcanoes. 2015-11-05. Retrieved 2018-11-09.

- ^ "Saba". Oregon State University – Volcano World. 2011-08-05. Retrieved 2018-11-09.

- ^ a b c "Hiking Trails". Saba Conservation Foundation. Retrieved 2018-11-09.

- ^ a b c d e "Saba Coastline". Dutch Caribbean Nature Alliance. Archived from the original on 2014-07-10. Retrieved 2018-11-09.

- ^ a b c d "Flora & Fauna". [Saba Conservation Foundation. Retrieved 2018-11-09.

- ^ "Saba National Park". Dutch Caribbean Nature Alliance. Archived from the original on 2018-10-12. Retrieved 2018-11-09.

- ^ a b "Les Fruits De Mer » Blog Archive » Extreme Shallow Snorkeling at the Saba Tide Pools". Retrieved 2024-01-11.

- ^ "Hiking | Saba Tourism". 2022-03-10. Retrieved 2024-01-11.

- ^ "Hiking on Saba | Sea Saba Dive Center". seasaba. Retrieved 2024-01-12.

- ^ Werner, Laurie. "Ultimate Caribbean Seclusion: The Under The Radar, Newly Reopened Island Of Saba". Forbes. Retrieved 2024-01-12.

- ^ a b c "AN006 Data Sheet". BirdLife International. Retrieved 2018-11-09.

- ^ "Biological Inventory of Saba" (PDF). www.sabapark.org. Carmabi Foundation.

- ^ van den Burg, Matthijs P.; Madden, Hannah; Debrot, Adolphe O. (20 May 2022), Population estimate, natural history and conservation of the melanistic <i>Iguana Iguana</i> population on Saba, Caribbean Netherlands, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, doi:10.1101/2022.05.19.492665, S2CID 248990505

- ^ van den Burg, Matthijs P.; Hylkema, Alwin; Debrot, Adolphe O. (21 September 2021). "Establishment of two nonnative parthenogenetic reptiles on Saba, Dutch Caribbean: Gymnophthalmus underwoodi and Indotyphlops braminus". Caribbean Herpetology: 1–5. doi:10.31611/ch.79. eISSN 2333-2468.

- ^ van den Burg, M. P.; Goetz, M.; Brannon, L.; Weekes, T. S.; Ryan, K. V.; Debrot, A. O. (23 March 2023). "An integrative approach to assess non‐native iguana presence on Saba and Montserrat: Are we losing all native <i>Iguana</i> populations in the Lesser Antilles?". Animal Conservation. doi:10.1111/acv.12869. eISSN 1469-1795. hdl:10261/306882. ISSN 1367-9430. S2CID 257731680.

- ^ "Saba Bank". Saba Conservation Foundation. Retrieved 2018-11-09.

- ^ "About Saba – Constitutional Status". www.sabagovernment.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-12. Retrieved 2019-01-22.

- ^ a b c "Island Governor – Introduction". www.sabagovernment.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-12. Retrieved 2019-01-22.

- ^ "Many Sabans vote for first time in the Second Chamber election". Saba News. 2017-03-16. Archived from the original on 2017-03-16. Retrieved 2019-01-22.

- ^ "Landslide victory for WIPM". Saba News. 2019-03-21. Archived from the original on 2019-03-22. Retrieved 2019-04-05.

- ^ "Island Governor – Functions". www.sabagovernment.com. Archived from the original on 2016-08-10. Retrieved 2019-01-22.

- ^ "Island Council – Council Members". www.sabagovernment.com. Archived from the original on 2018-12-28. Retrieved 2019-01-22.

- ^ "Island Council Functions". www.sabagovernment.com. Archived from the original on 2019-01-01. Retrieved 2019-01-22.

- ^ a b "St. Martin News Network - New Saba Island Council installed, Commissioners appointed". smn-news.com. Retrieved 2024-04-15.

- ^ "New Island Council, Commissioners sworn in – Saba News". 2021-10-24. Archived from the original on 2021-10-24. Retrieved 2021-10-24.

- ^ "Julio Every sworn into Island Council". Saba News. 2023-11-29. Retrieved 2024-04-15.

- ^ "Island Council". Public Entity Saba. Retrieved 2024-04-15.

- ^ "Executive Council Functions". www.sabagovernment.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-12. Retrieved 2019-01-22.

- ^ a b "Executive Council – Members". www.sabagovernment.com. Archived from the original on 2016-08-10. Retrieved 2019-01-22.

- ^ "Government of Saba Departments – Contact Info". www.sabagovernment.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-12. Retrieved 2019-01-22.

- ^ "Division of portfolios in new Executive Island Council". Saba News. 2019-04-04. Archived from the original on 2019-04-07. Retrieved 2019-04-05.

- ^ "Division of Portfolios" (PDF). Public Entity Saba. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- ^ "Saba: population 2011–2020". Statista. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ Soloway, L.E.; Demerath, E.W.; Ochs, N.; James, G.D.; Little, M.A.; Bindon, J.R.; Garruto, R.M. (2009). "Blood Pressure and Lifestyle on Saba, Netherlands Antilles". American Journal of Human Biology. 21 (3): 319–325. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20862. PMC 2910626. PMID 19189411.

- ^ "Saba University School of Medicine | Caribbean Medical School". Saba.edu. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- ^ a b c d Netherlands, Statistics (2019-04-04). "Caribbean Netherlands; Spoken languages and main language, characteristics". Statistics Netherlands. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ Dijkhoff, Marta; Kowenberg, Silvia; Tjon Sie Fat, Paul (2008). "Chapter 215: The Dutch-speaking Caribbean Die niederländischsprachige Karibik". In Ammon, Ulrich; Dittmar, Norbert; Mattheier, Klaus J.; Trudgill, Peter (eds.). Sociolinguistics / Soziolinguistik. Vol. 3. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 2105, 2108. ISBN 978-3110199871.

- ^ Trugill, Peter; Hannah, Jane (2017). The Handbook of World Englishes (6 ed.). p. 115.

- ^ Johnson, Theodore R. (2016). A Lee Chip: A Dictionary and Study of Saban English. With Grammar and Pronunciation Sections by Caroline Myrick. Language & Life Project.

- ^ "Dictionary of Saba English to preserve island's dialect". The Daily Herald. Published on Saba-News.com. March 30, 2016. Archived from the original on March 30, 2016.

- ^ a b "Religion in Caribbean Netherlands". Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. 2014-12-18.

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon; Baumann, Martin (2010-09-21). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, 2nd Edition [6 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-204-3.

- ^ Henry, Esther (30 January 2018). "Saba churches raise funds for renovations after Irma | Caribbean Network". caribbeannetwork.ntr.nl. Retrieved 2022-10-14.

- ^ "The Church of England On Saba". The Saba Islander. 2017-02-01. Retrieved 2022-10-14.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Church of Rome on Saba". The Saba Islander. 2014-02-28. Retrieved 2022-10-14.

- ^ a b Crane, Julia G. (1966). Concomitants of Selective Emigration on a Caribbean Island. Columbia University.

- ^ a b "History of Health Care on Saba". Saba Cares Foundation. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ "Grand opening of renovated A.M. Edwards Medical Center". The Daily Herald. 16 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Healthcare: Saba Cares". Saba Tourist Bureau. 2022-05-19. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ "Fort Bay Harbor: Facilities". www.sabaport.com. Fort Bay, Saba: The Harbor Office. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ "Diving". Saba Tourist Bureau. 2018-06-22. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ "Burgerlijk wetboek BES, boek 1" (in Dutch). Government of the Netherlands. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ "Aanpassingswet openbare lichamen Bonaire, Sint Eustatius en Saba" (in Dutch). Government of the Netherlands. 1 September 2010. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ "Saba records first gay marriage on Tuesday". St. Maarten Time. 4 December 2012. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ "First Gay Marriage In Dutch Caribbean". Curaçao Chronicle. 4 December 2012. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ "First same-gender wedding in Caribbean Netherlands". Dutch Caribbean Legal Portal. 5 December 2012. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ "Plein". Pleinplus.nl. 2009-12-02. Archived from the original on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- ^ a b c "Welcome to Saba!". Saba Tourist Bureau. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ^ a b Witte, Brian (2012-12-29). "Diving off Saba, the Caribbean's unspoiled queen". Lubbock Avalanch-Journal. Retrieved 2022-08-14.

- ^ "SCF to receive subsidies for refurbishment of hyperbaric chamber and mooring system". SabaNews. 23 November 2012. Archived from the original on 30 July 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ^ "Saba Dutch Caribbean Travel Guide". LukeTravels.com. Retrieved 2007-10-06.

- ^ a b "About Saba | Saba Tourism". www.sabatourism.com. 2018-06-21. Archived from the original on 2022-08-28. Retrieved 2022-09-01.

- ^ Tweddle, Andy (20 January 2011). "Five of the smallest airports in the world". Business Traveller. Panacea Publishing. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ^ "The Ladder | Saba Tourism". www.sabatourism.com. 2022-03-11. Retrieved 2022-09-01.

- ^ "Energy Snapshot Saint Martin & Sint Maarten" (PDF). National Renewable Energy Laboratory. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-06-16. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ a b "Towards 100% sustainable energy on the Caribbean island of Saba". Leds Global Partnership. Low Emission Development Strategies Global Partnership (LEDS GP). 2015-12-10. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ^ "Solar Parks | Saba Electric Company". powerupsaba.com. Retrieved 2024-01-26.

- ^ "Welcome to Saba, a different Caribbean!". The Daily Herald. 7 December 2023.

- ^ MacGregor, Sandra. "Discover Saba: The Sustainable Jewel Of The Caribbean". Forbes. Retrieved 2024-01-26.

- ^ "Home". Sacred Heart Primary School. Retrieved 2018-11-28.

- ^ "Home". Saba Comprehensive School. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- ^ a b Scheffler, Daniel (June 27, 2016). "The Best Caribbean Island You've Never Heard Of". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ "Saba Radio Stations". RadioStationWorld.com. Retrieved 2018-11-15.

- ^ "Q93.9 FM". Archived from the original on 2017-07-10. Retrieved 2018-11-15.

- ^ "Saba News". Saba News. Retrieved 2020-09-15.

- ^ "Museums: Harry L. Johnson MuseumS". Saba Tourist Bureau. 2018-06-29. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ "Harry L Johnson Museum". www.museum-saba.com. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ "Museums: Major Osmar R. Simmons Museum". Saba Tourist Bureau. 2018-06-30. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ "Cruyff Courts Saba/Sint Maarten/Sint Eustatius". Windward Roads B.V. 1 January 2007.

- ^ "1st Cruyff Court Dutch Caribbean Futsal Championship 2007 (Aruba)". RSSSF. 6 February 2008.

- ^ "Saba and St. Eustatius compete in softball". Pearl FM Radio – Pearl of the Caribbean. 27 June 2011.

- ^ "SVG's volleyball taps into NORCECA's resources". Searchlight. 2014-04-08. Retrieved 2024-04-05.

Further reading

[edit]- Bolles, Joshua K. (2013). Johnson, Will (ed.). Caribbean Interlude: The Story of Saba the Rock. Will Johnson. ISBN 978-1-4675-6637-7.. A first-person account by an American journalist of the eleven months he spent on Saba in 1931, illustrated with photographs of Saba at that time.

- Johnson, Theodore R. (2016). A Lee Chip: A Dictionary and Study of Saban English. Raleigh, NC: Language and Life Project at North Carolina State University. ISBN 978-0-578-17558-4.. A dictionary, grammar and phonological description, with a history of Saban English in the introduction.

- Nielsen, Suzanne; Schnabel, Peter (2007). Folk Remedies on a Caribbean Island, the Story of Bush Medicine on Saba. Author. ISBN 9789990407594. Aguide to many of the plants of Saba, including their medicinal properties.

- Rahn, Jennifer (2017). "Saba and St. Eustatius (Statia)". Casey D. Allen, ed. Landscapes and Landforms of the Lesser Antilles. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Cham. pp. 61–84 doi:10.1007/978-3-319-55787-8_6. ISBN 978-3-319-55785-4.

- Shrout, Richard Neil (1989). "The Mysterious Island of Saba" (PDF). South Florida History Magazine. No. 2. pp. 3–7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-18. Retrieved 2017-11-16 – via HistoryMiami.

External links

[edit]- Saba (island)

- Caribbean special municipalities of the Netherlands

- Countries and territories where Dutch is an official language

- Countries and territories where English is an official language

- Dependent territories in the Caribbean

- Important Bird Areas of the Dutch Caribbean

- Islands of the Netherlands Antilles

- Leeward Islands (Caribbean)