Raffles stories and adaptations

A. J. Raffles is a British fictional character – a cricketer and gentleman thief – created by E. W. Hornung. Between 1898 and 1909, Hornung wrote a series of 26 short stories, two plays, and a novel about Raffles and his fictional chronicler, Harry "Bunny" Manders.

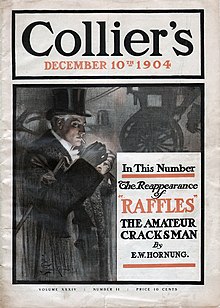

The first story, "The Ides of March", appeared in the June 1898 edition of Cassell's Magazine.[1] The early adventures were collected in The Amateur Cracksman[2] and continued with The Black Mask (1901).[3] The last collection, A Thief in the Night (1904)[4] and the novel Mr. Justice Raffles (1909)[5] tell of adventures previously withheld. The novel was poorly received, and no further stories were published.[6]

Hornung dedicated the first collection of stories, The Amateur Cracksman, to his brother-in-law, Arthur Conan Doyle, intending Raffles as a "form of flattery."[1] In contrast to Conan Doyle's Holmes and Watson, Raffles and Bunny are "something dark, morally uncertain, yet convincingly, reassuringly English."[7]

I think I may claim that his famous character Raffles was a kind of inversion of Sherlock Holmes, Bunny playing Watson. He admits as much in his kindly dedication. I think there are few finer examples of short-story writing in our language than these, though I confess I think they are rather dangerous in their suggestion. I told him so before he put pen to paper, and the result has, I fear, borne me out. You must not make the criminal a hero.

Raffles is an antihero. Although a thief, he "never steals from his hosts, he helps old friends in trouble, and in a subsequent volume he may or may not die on the veldt during the Boer War."[8] Additionally, the "recognition of the problems of the distribution of wealth is [a] recurrent subtext" throughout the stories.[1]

According to the Strand Magazine, these stories made Raffles "the second most popular fictional character of the time," behind Sherlock Holmes.[1] They have been adapted to film, television, stage, and radio, with the first appearing in 1903.

Plot

[edit]The "Raffles" stories have two distinct phases. In the first phase, Raffles and Bunny are men-about-town who also commit burglaries. Raffles is a famous gentleman cricketer, a marvellous spin bowler who is often invited to social events that would be out of his reach otherwise. "I was asked about for my cricket", he comments after this period is over. It ends when they are caught and exposed on an ocean voyage while attempting another theft; Raffles dives overboard and is presumed drowned. These stories were collected in The Amateur Cracksman.[2] Other stories set in this period, written after Raffles had been "killed off", were collected in A Thief in the Night.[4]

The second phase begins some time later when Bunny – having served a prison sentence – is summoned to the house of a rich invalid. This turns out to be Raffles himself, back in England in disguise. Then begins their "professional" period, exiled from Society, in which they are straightforward thieves trying to earn a living while keeping Raffles's identity a secret. They finally volunteer for the Boer War, where Bunny is wounded and Raffles dies in battle after exposing an enemy spy. These stories were originally collected in The Black Mask, although they were subsequently published in one volume with the phase one stories.[3] The last few stories in A Thief in the Night were set during this period as well.[4]

Raffles was never quite the same after his reappearance. The "classic" Raffles elements are all found in the first stories: cricket, high society, West End clubs, Bond Street jewellers – and two men in immaculate evening dress pulling off impossible robberies.

Characters

[edit]A. J. Raffles

[edit]Raffles is, in many ways, a deliberate inversion of Holmes – he is a "gentleman thief", living at the Albany, a prestigious address in London, playing cricket for the Gentlemen of England and supporting himself by carrying out ingenious burglaries. He is called the "Amateur Cracksman", and often, at first, differentiates between himself and the "professors" – professional criminals from the lower classes.[1][2]

Bunny Manders

[edit]Bunny Manders, a struggling journalist, is Watson to Raffles' Holmes, his partner and chronicler. They met initially at school and then again on the night Bunny intended to commit suicide after writing bad cheques to cover gambling debts. Raffles, also penniless, but thriving, persuaded Bunny to join him instead.[1][2]

Inspector Mackenzie

[edit]The most notable recurring character in the stories aside from Raffles and Bunny is Inspector Mackenzie, a Scottish detective from Scotland Yard. Mackenzie is an adversary to Raffles and appears in "Gentlemen and Players", "The Return Match", "The Gift of the Emperor", and Mr. Justice Raffles. He is first mentioned in "A Costume Piece" and is also referenced by name in "The Chest of Silver". He is probably the "canny man at Scotland Yard" mentioned in "The Rest Cure".

Mackenzie was based on Melville Leslie Macnaghten, the Chief Constable of the Criminal Investigation Department at Scotland Yard, according to Richard Lancelyn Green.[9] Owen Dudley Edwards wrote that the character Inspector MacDonald in The Valley of Fear seems to have been inspired by Inspector Mackenzie.[10]

Though Mackenzie only directly appears in four of the Raffles stories, he is used as a more major character in several adaptations of Raffles, for example the 1977 television series Raffles. There are a few other minor recurring characters in the Raffles stories, such as the rival thief Crawshay, who appears in two early stories and is mentioned in "The Chest of Silver".

List of stories

[edit]

The Raffles stories include three short story collections and one novel. Most of the short stories appeared in magazines before being published in book form.

- The Amateur Cracksman (1899):

- "The Ides of March", first published in June 1898 in Cassell's Magazine.

- "A Costume Piece", first published in July 1898 in Cassell's Magazine.

- "Gentlemen and Players", first published in August 1898 in Cassell's Magazine.

- "Le Premier Pas", first published in this collection.

- "Wilful Murder", first published in this collection.

- "Nine Points of the Law", first published in September 1898 in Cassell's Magazine.

- "The Return Match", first published in October 1898 in Cassell's Magazine.

- "The Gift of the Emperor", first published in November 1898 in Cassell's Magazine.

- The Black Mask (1901) – stories take place after "The Gift of the Emperor":

- "No Sinecure", first published in January 1901 in Scribner's Magazine.

- "A Jubilee Present", first published in February 1901 in Scribner's Magazine.

- "The Fate of Faustina", first published in March 1901 in Scribner's Magazine.

- "The Last Laugh", first published in April 1901 in Scribner's Magazine.

- "To Catch a Thief", first published in May 1901 in Scribner's Magazine.

- "An Old Flame", first published in June 1901 in Scribner's Magazine.

- "The Wrong House, first published in September 1901 in Scribner's Magazine.

- "The Knees of the Gods", first published in this collection.

- A Thief in the Night (1905) – all except the last two take place before "The Gift of the Emperor":

- "Out of Paradise", first published in December 1904 in Collier's Weekly.

- "The Chest of Silver", first published in January 1905 in Collier's Weekly.

- "The Rest Cure", first published in February 1905 in Collier's Weekly.

- "The Criminologists' Club", first published in March 1905 in Collier's Weekly.

- "The Field of Philippi", first published in April 1905 in Collier's Weekly.

- "A Bad Night", first published in June 1905 in Pall Mall Magazine.

- "A Trap to Catch a Cracksman", first published in July 1905 in Pall Mall Magazine.

- "The Spoils of Sacrilege", first published in August 1905 in Pall Mall Magazine.

- "The Raffles Relics", first published in September 1905 in Pall Mall Magazine.

- "The Last Word", shorter than the other stories, first published in this collection.

- Mr. Justice Raffles (1909), takes place sometime before "The Gift of the Emperor".

Adaptations

[edit]Film

[edit]There have been numerous films based on Raffles and his adventures, including:

- Raffles, the Amateur Cracksman (1905), starring J. Barney Sherry.[1]

- Three short films released in Denmark in 1908 featured Raffles and Sherlock Holmes. These films were titled "Sherlock Holmes in Deathly Danger" (also called "Sherlock Holmes Risks His Life"), "Raffles Escapes From Prison", and "The Secret Document". Forrest Holger-Madsen portrayed Raffles and Viggo Larsen portrayed Sherlock Holmes. Otto Dethlefsen appeared as Professor Moriarty in the first film. The films were produced by Nordisk.[11]

- A film titled Raffles was released by Nordisk in 1910.[11]

- An Italian serial titled Raffles was released in 1911.[11]

- The Van Nostrand Tiara (1913), starring Reggie Morris.

- Raffles, the Amateur Cracksman (1917), starring John Barrymore and Frank Morgan.[1][12]

- Mr. Justice Raffles (1921) starring Gerald Ames.[13]

- Raffles, the Amateur Cracksman (1925), with House Peters.[14]

- Raffles (1930), featuring Ronald Colman and Bramwell Fletcher.[15]

- The Return of Raffles (1932) starring George Barraud and Claud Allister.[16]

- Raffles (1939), starring David Niven and Douglas Walton.[17]

- Raffles (1958), with Rafael Bertrand as a Mexican version of Raffles.[11]

Television

[edit]- Raffles (1975), a made-for-TV film, with Anthony Valentine portraying Raffles and Christopher Strauli playing his partner Bunny Manders.[18]

- Valentine and Strauli reprised their roles in a television series titled Raffles, produced by Yorkshire Television in 1977 and scripted by Philip Mackie. Victor Carin portrayed Inspector Mackenzie. The series was intermittently repeated on ITV3 in 2006, and has been released on DVD.[8][19]

- A version of Raffles makes an appearance in the Sherlock Holmes TV film Incident at Victoria Falls under the name Stanley Bullard and played by Alan Coates.[20]

- The Gentleman Thief (2001), starring Nigel Havers.[21]

Radio and audio

[edit]- Frederic Worlock voiced Raffles in a 1934 CBS radio series, Raffles, the Amateur Cracksman.[22] The scripts were adapted by Charles Tazewell.[23]

- A radio adaptation of "The Ides of March" aired on 9 December 1941 on the BBC Forces Programme, with Malcolm Graeme as Raffles and Ronald Simpson as Bunny. It was adapted by John Maitland and produced by John Cheatle.[24]

- Horace Braham voiced Raffles in CBS radio productions between 1942 and 1945.[22]

- Six radio episodes with Frank Allenby as Raffles and Eric Micklewood as Bunny were broadcast on the BBC Light Programme between 3 December 1945 and 14 January 1946. The producer was Leslie Stokes.[25]

- Austin Trevor voiced Raffles with Lewis Stringer as Bunny in a radio adaptation of Mr. Justice Raffles, adapted and produced by Val Gielgud. It aired on the BBC Home Service on 8 February 1964. Duncan McIntyre voiced Inspector Mackenzie.[26]

- Raffles (1985–1993), a BBC radio series starring Jeremy Clyde as Raffles and Michael Cochrane as Bunny Manders. The series included an adaptation of the play The Return of A. J. Raffles.

- Raffles, the Gentleman Thief (2004–present), a series on the American radio show Imagination Theatre starring John Armstrong as Raffles and Dennis Bateman as Bunny Manders. Raffles and Bunny encounter Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson in an episode of another Imagination Theatre radio series, The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes.

- Audiobooks such as Raffles, The Amateur Cracksman read by David Rintoul.[27]

- "Mr. Raffles (Man, It Was Mean)", a 1974 pop single by Steve Harley & Cockney Rebel, was inspired by the character.

- The Big Finish audio play The Suffering by Jacqueline Rayner has the First Doctor comment that he learned his house breaking techniques "from Raffles". He almost certainly means nothing more than he picked up techniques from reading Hornung's stories, but since Sherlock Holmes appears as a real character in the Doctor Who universe, it is possible that A.J. Raffles is real too.[28]

Theatre

[edit]- The story of A. J. Raffles was first performed on Broadway as Raffles, The Amateur Cracksman on 27 October 1903 at the Princess Theatre.[29] The play moved to the Savoy Theatre in February 1904 and closed out in March of that year racking up 168 performances. It starred Kyrle Bellew as Raffles, a young Clara Blandick as Gwendolyn and E. M. Holland as Captain Bedford.[30] The play was co-written by E. W. Hornung and Eugene Presbrey. It premiered in London on 12 May 1906, with Gerald du Maurier as Raffles.[31] André Brulé starred as Raffles in a production that opened on 14 June 1907 at the Théatre Réjane, Paris. The play opened at the Teatro de la Comedia, Madrid, on 11 February 1908.[32] Eille Norwood played Raffles in a touring version of the play in 1909.[33]

- In Langdon McCormick's 1905 play, The Burglar and the Lady, Raffles went up against Arthur Conan Doyle's famous fictional detective Sherlock Holmes. Former boxer "Gentleman Jim" Corbett played Raffles, who was portrayed as an American to match his casting. McCormick did not secure permission from either Doyle or Hornung to use their characters. A 1914 movie adaptation of the play removed Holmes but kept Raffles, again played by Corbett.[34]

- The play A Visit from Raffles, by E. W. Hornung and Charles Sansom, opened on 1 November 1909 at the Empress Theatre, Brixton. It starred H. A. Saintsbury as Raffles.[32]

- Graham Greene wrote a play called The Return of A. J. Raffles which differs from the Hornung canon on several points, including reinventing Raffles and Bunny as a homosexual couple.[35][36] Denholm Mitchell Elliott starred as Raffles in the 1975 premiere at the Aldwych Theatre.[37] Raffles has also been played in other productions by John Neville (1979), Jeremy Child (1979), and Brian Protheroe (1994). The play was adapted for radio in 1993 as part of the BBC radio series with Jeremy Clyde as Raffles.

Comics

[edit]- In the Doctor Who comic strip Character Assassin by Scott Gray (Doctor Who Magazine no.311, 12 December 2001), A. J. Raffles is a member of the villainous Sisyphean Society's inner circle in the Land of Fiction. The Master quickly kills him along with the other members of the Society.

- The character was mentioned in the 2007 epistolary graphic novel The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Black Dossier.[38] Following this he recently appeared as a central character in the first chapter of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Volume III: Century, set in 1910.[39]

- Raffles, Gentleman Thug is a strip in Viz that features a character who shares his name (plus the name of his assistant, Bunny) with the literary Raffles. He is depicted as an upper-class, late Victorian or early Edwardian version of a 'chav'.

Literary pastiches

[edit]- The Raffles character was continued by Barry Perowne with the approval of the Hornung Estate. Published in the story paper The Thriller during the 1930s and early 1940s,[1] his series featured Raffles as a fairly typical contemporary pulp adventure hero and plays the role of detective alongside that of thief. When he picked up the series again in the 1950s, and once again during the 1970s, the stories were set closer to the late Victorian-setting of the original stories. Over the course of 50 years, off and on, Perowne produced around 60 short stories, some at novella length, and five novels featuring Raffles. Rare for a pastiche writer, Perowne's stories have been compared favourably with the originals.[40]

- Jon L. Breen's story "Ruffles versus Ruffles" is based on the conceit that Hornung's Raffles and Perowne's Raffles are separate people, playing off the differing characterisation used by the two authors.[41]

- The 1977 novel Raffles, by David Fletcher, is a fresh re-write of many of Hornung's original stories, deriving from the television series of the same year.[42]

- Peter Tremayne wrote the 1991 novel The Return of Raffles in which Raffles becomes involved in a plot between rival spies.[43] Although announced as the "first of a new series of Raffles adventure," it remains a single volume.

- Around the turn of the 21st Century, John Hall wrote eight Raffles pastiches, some of which appeared in the Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine. Some were adaptions of scripts he wrote earlier for the Imagination Theatre radio series. They were collected in the 2007 book The Ardagh Emeralds.[44]

- Adam Corres authored the 2008 novel Raffles and the Match-Fixing Syndicate,[45] a modern crime thriller in which A. J. Raffles, a master of gamesmanship, explores the corrupt world of international cricket match fixing.

Raffles and Holmes

[edit]- John Kendrick Bangs authored a 1906 novel, R. Holmes & Co.,[46] starring Raffles' grandson (and Sherlock Holmes's son, by Raffles' daughter Marjorie), Raffles Holmes. The novel's second chapter tells the story of Holmes's pursuit of Raffles and his growing affection for Raffles's daughter. Bangs also wrote Mrs Raffles,[47] in which Raffles's sidekick Bunny Manders teams up in America with the cracksman's hitherto-unchronicled wife.

- Carolyn Wells wrote several short parodies in which Sherlock Holmes leads a group called the International Society of Infallible Detectives. Raffles is depicted as a member of the society, along with other characters such as C. Auguste Dupin and Arsène Lupin. Raffles appears in four of the stories, which were published in magazines: "The Adventure of the 'Mona Lisa'" (1912),[48] "Sure Way to Catch Every Criminal. Ha! Ha!" (1912),[49] "The Adventure of the Lost Baby" (1913),[50] and "The Adventure of the Clothes-line" (1915).[51]

- Several of Barry Perowne's Raffles short stories feature or reference Sherlock Holmes, including: "The Victory Match"; "The Baskerville Match" and "Raffles and an American Night's Entertainment".

- In 1932, Hugh Kingsmill's "The Ruby of Khitmandu", in which Raffles and Bunny were pitted against Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, was published in the April issue of The Bookman. A portion of the story was republished in the collection The Misadventures of Sherlock Holmes (1944, edited by Ellery Queen).

- Philip José Farmer put Raffles and Manders into a science-fictional situation in his story, "The Problem of the Sore Bridge – Among Others", in which he and Bunny solve three mysteries unsolved by Sherlock Holmes and save humanity from alien invasion.[52]

- In one of Robert L. Fish's Schlock Homes stories, "The Adventure of the Odd Lotteries" (1980), Homes and Watney encounter a cracksman and hypochondriac known as "A.J. Lotteries."[53]

- Raffles and Bunny feature in Moriarty: The Hound of the D'Ubervilles (2011), by Kim Newman, in a chapter depicting the gathering of the world's greatest criminals.[54]

- In 2011 and 2012 Richard Foreman published a series of six Raffles stories, collected in a single volume, Raffles: The Complete Innings.[55] These stories, contemporaneous with The Amateur Cracksman, begin with "The Gentleman Thief," in which Raffles and Bunny are hired by Sherlock Holmes to steal a stolen letter. Later stories in the sextet see Raffles and Bunny encounter H. G. Wells and Irene Adler. Foreman's Raffles is also more moralistic than the original: the gentleman thief often donates part of his ill-gotten gains to various charitable causes.

Cameo appearances

[edit]- Raffles makes a cameo appearance in Kim Newman's Anno Dracula (1992). Although never mentioned by name, the character is described as an amateur cracksman (a reference to the title of the first short story collection), and mutters the epigram, "You play what's chucked at you, I always say."[56]

- Raffles and Bunny make a minor appearance in Lost in a Good Book, a 2004 novel written by Jasper Fforde. They are pulled out of the literary world into the real world to help crack a safe containing the stolen manuscript of Shakespeare's Cardenio.[57]

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bleiler, Richard. "Raffles: The Gentleman Thief". Strand Magazine. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d Hornung, E. W. (29 April 2013). The Amateur Cracksman. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1484852606.

- ^ a b Hornung, E. W. (29 April 2013). The Black Mask. Ulverscroft Softcover. ISBN 978-1444808094.

- ^ a b c Hornung, E. W. (22 July 2013). A Thief in the Night. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1491069363.

- ^ Hornung, E. W. (25 December 2012). Mr. Justice Raffles. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1481841856.

- ^ Rowland, Peter (1999). Raffles and His Creator. London: Nekta Publications. pp. 190 & 194–95. ISBN 0953358321.

- ^ Stuart, Evers (28 April 2009). "The Moral Riddles of AJ Raffles". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Quinn, Anthony (10 November 2012). "Book of a Lifetime: Raffles by EW Hornung". The Independent.

- ^ Hornung (2003), p. 156, "Notes" by Richard Lancelyn Green.

- ^ Doyle, Arthur Conan (1994) [1915]. Edwards, Owen Dudley (ed.). The Valley of Fear. Oxford University Press. p. 181. ISBN 9780192823823. Stated under "Explanatory Notes" by Owen Dudley Edwards.

- ^ a b c d Pitts, Michael R. (1991). Famous Movie Detectives II. Metuchen, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0810823457.

- ^ Irving, George (Director) (1917). Raffles, the Amateur Cracksman (Motion picture). Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Quiribet, Gaston and Gerald Ames (Director) (1921). Mr. Justice Raffles (Motion picture). Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Baggot, King (Director) (1925). Raffles (Motion picture). Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Fitzmaurice, George and Harry D'Abbadie D'Arrast (Director) (1930). Raffles (Motion picture). Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Markham, Mansfield (Director) (1932). The Return of Raffles (Motion picture). Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Wood, Sam (Director) (1939). Raffles (Motion picture). Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "Raffles The Amateur Cracksman (1975)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ^ Raffles (Television production). 1977. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Corcoran, Bill (Director) (1991). Sherlock Holmes: Incident at Victoria Falls (Television production). Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ Banks-Smith, Nancy (11 July 2001). "Cutglass vowels and strangled yowls in the last summer of peace". The Guardian. London. p. 22.

- ^ a b Pitts, Michael R. (2004). Famous Movie Detectives III. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. p. 301. ISBN 978-0810836907.

- ^ "Raffles Saves Crime For Air" (PDF). Radio Guide. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ "The Ides of March". BBC Genome. BBC. 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ "Frank Allenby as 'Raffles'". BBC Genome. BBC. 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ "Saturday-Night Theatre". BBC Genome. BBC. 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ Rintoul, David (Narrator) (2013). Raffles: The Amateur Cracksman (Audiobook). Audible.com. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Doctor Who – The Companion Chronicles; Sherlock Holmes appears as a character in the Doctor Who novel All-Consuming Fire.

- ^ Bordman, Gerald; Hischak, Thomas S. (January 2004). The Oxford Companion to American Theatre. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195169867. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "Raffles, the Amateur Cracksman". ibdb.com. IBDB. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ Rowland, Peter (1999). Raffles and His Creator: The Life and Works of E. W. Hornung. London: Nekta Publications. p. 261. ISBN 0-9533583-2-1.

- ^ a b Horning (2003), pp. xlviii–lvi, "Further Reading" by Richard Lancelyn Green.

- ^ "Eille Norwood", Who's Who in the Theatre, Volume 3, ed. John Parker, Boston: Small, Maynard, and Co., 1912, p. 372.

- ^ Kabatchnik, Amnon (2008). Sherlock Holmes on the Stage: A Chronological Encyclopedia of Plays Featuring the Great Detective. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. pp. 47–51. ISBN 978-0-8108-6125-1. OCLC 190785243.

- ^ Greene, Graham (4 December 1975). The Return of A. J. Raffles. The Bodley Head. ISBN 0370106024.

- ^ Nightingale, Benedict (21 December 1975). "Graham Greene's 'Raffles' Is No Sherlock Holmes". The New York Times.

- ^ "The Return of A J Raffles". Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Moore, Alan (4 November 2008). The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Black Dossier. WildStorm. ISBN 978-1401203078.

- ^ Moore, Alan (19 May 2009). The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Volume 3: Century #1 1910. Top Shelf Productions. ISBN 978-1603090001.

- ^ David Vinyard's review of Raffles Revisited is typical.

- ^ Breen, Jon L. Ruffles versus Ruffles. Ellery Queen. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Fletcher, David (1977). Raffles. Putnam. ISBN 0399119485.

- ^ Tremayne, Peter (July 1991). The Return of Raffles. Severn House Pub Ltd. ISBN 0727841408.

- ^ Hall, John (2007). The Ardagh Emeralds. Linford Mystery Library, F. A. Thorp (Publishing). ISBN 9781846178672.

- ^ Corres, Adam (14 January 2008). Raffles and the Match-Fixing Syndicate. Grosvenor House Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781906210625.

- ^ Bangs, John Kendrick (2013). R. Holmes & Co. Project Gutenberg. ISBN 978-3955630782.

- ^ Bangs, John Kendrick (3 January 2014). Mrs. Raffles. Project Gutenberg. ISBN 978-1494875060.

- ^ "The Century illustrated monthly magazine. v.83 1912". HathiTrust Digital Library. p. 514. hdl:2027/inu.32000000491920. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Panek, LeRoy Lad (2006). The Origins of the American Detective Story. McFarland & Company. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-7864-8138-5.

- ^ "Collected Short Stories by Carolyn Wells". Project Gutenberg Australia. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Wells, Carolyn (1915). . The Century Magazine – via Wikisource.

- ^ Farmer, Philip José (April 1981). "The Problem of the Sore Bridge – Among Others". Riverworld and Other Stories. The Gregg Press science fiction series. Gregg Press. ISBN 0839826184.

- ^ Fish, Robert L. (1 August 1990). "The Adventure of the Odd Lotteries". Schlock Homes: The Complete Bagel Street Saga. Gaslight Publications. ISBN 0934468168.

- ^ Newman, Kim (4 October 2011). Moriarty: The Hound of the D'Ubervilles. Titan Books. ISBN 978-0857682833.

- ^ Foreman, Richard (25 March 2013). Raffles: The Complete Innings. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1480203136.

- ^ Newman, Kim (24 May 2011). Anno Dracula. Titan Books. ISBN 978-0857680839.

- ^ Fforde, Jasper (24 February 2004). Lost in a Good Book (A Thursday Next Novel). Penguin Books. ISBN 0142004030.

Bibliography

- Larance, Jeremy. "The A. J. Raffles Stories Reconsidered: Fall of the Gentleman Ideal." English Literature in Transition, 1880–1920. 57.1 (2014): 99–125.

- Rowland, Peter. Raffles and His Creator: The Life and Works of E. W. Hornung, Nekta Publications, London, 1999. ISBN 0953358321

- Hornung, E. W. (2003) [1899]. Richard Lancelyn Green (ed.). Raffles, the Amateur Cracksman (Reprinted ed.). London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1856132824.

External links

[edit]- "Arthur J. Raffles".

- Raffles stories on Project Gutenberg

A.J. Raffles public domain audiobook at LibriVox

A.J. Raffles public domain audiobook at LibriVox- "Raffles and Miss Blandish", Horizon 10.58 (1944) – an essay by George Orwell

- "Raffles the Amateur Cracksman", a site about the 1970s TV series

- "Raffles Redux", a site with all of the Raffles Stories, complete with Annotations and Original Illustrations