Radcliffe, Greater Manchester

| Radcliffe | |

|---|---|

A prominent landmark, St Thomas and St John with St Philip Church | |

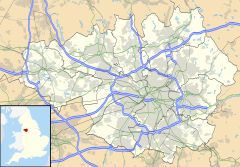

Location within Greater Manchester | |

| Population | 29,950 [1] |

| OS grid reference | SD785075 |

| • London | 170 mi (274 km) SE |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | MANCHESTER |

| Postcode district | M26 |

| Dialling code | 0161 |

| Police | Greater Manchester |

| Fire | Greater Manchester |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

Radcliffe is a market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Bury, Greater Manchester, England.[2] It lies in the Irwell Valley 7 miles (11 km) northwest of Manchester and 3 miles (5 km) southwest of Bury and is contiguous with Whitefield to the south. The disused Manchester Bolton & Bury Canal bisects the town.

Evidence of Mesolithic, Roman and Norman activity has been found in Radcliffe and its surroundings. A Roman road passes through the area, along the border between Radcliffe and Bury. Radcliffe appears in an entry of the Domesday Book as "Radeclive" and in the High Middle Ages formed a small parish and township centred on the Church of St Mary and the manorial Radcliffe Tower, both of which are Grade I listed buildings.

Plentiful coal in the area facilitated the Industrial Revolution, providing fuel for the cotton spinning and papermaking industries. By the mid-19th century, Radcliffe was an important mill town with cotton mills, bleachworks and a road, canal and railway network.[3]

At the 2011 Census, Radcliffe had a population of 29,950.[1] Radcliffe is predominantly a residential area whose few remaining cotton mill buildings are now occupied by small businesses.[3][4]

History

[edit]Toponymy

[edit]The name Radcliffe is derived from the Old English words read and clif,[5] meaning "the red cliff or bank",[6] on the River Irwell in the Irwell Valley. The Domesday Book records the name as "Radeclive".[5][7] Other archaic spellings include "Radclive" (recorded in 1227), and "Radeclif" (recorded in 1309 and 1360).[7] The Radcliffe family took its name from the town.[8]

Early history

[edit]The first human settlements in the area, albeit seasonal, are thought to have been as far back as 6,000BC during the Mesolithic period. Archaeological excavations in 1949 at Radcliffe Ees (a level plain along the north bank of the Irwell, formed by retreating glacial deposits during the previous ice age)[9] found evidence of pre-historic activity, suggesting a lake village site, but dating techniques of the time were unreliable. Further investigations in 1961 revealed rows of sharpened posts and worked timbers, but no further dating evidence was collected. In 1911, while repairs to the bridge at Radcliffe Bridge were underway, a stone axe-hammer was found in the river bed. The 8.5-inch (22 cm) large tool artefact weighs 4 pounds (1.8 kg) and is made from polished Quartzite, with a bore to take a shaft.[10][11]

South of the present-day Withins reservoir is a possible location for a Hengi-form Tumulus.[12] During the Roman period, a Roman road passed through the area on a south-east to north-west axis; tracing an alignment with the modern border between Radcliffe and Bury.[13] The route linked the Roman forts of Mamucium (Manchester) and Bremetennacum (Ribchester).[14] The approximate route was through Higher Lane in nearby Whitefield, through Dales Lane and across the Irwell over Radcliffe Ees through the site of the former East Lancashire Paper Mill. The route passes up Croft Lane, over Cross Lane and over the route of the Manchester Bolton & Bury Canal under the 10¾ milestone. It then crosses Bury and Bolton Road, and heads through Higher Spen Moor.[15]

Other than placenames, little information about the area survives from the Dark Ages. Radcliffe was likely moorland and swamps.[8]

Following the 11th century Norman conquest of England, Radcliffe became a parish and township in the hundred of Salford, and county of Lancashire.[16] One of only four parishes from the hundred mentioned in the Domesday Book and held by Edward the Confessor as a Royal Manor,[8] it initially consisted of two hamlets; Radcliffe, near to the border with Bury and centred on the Medieval Church of St Mary and the manorial Radcliffe Tower, and further to the west Radcliffe Bridge, at a crossing of the Irwell.[7] As a Royal Manor, the hide may originally have been up to four times the size it was when it was recorded in 1212 as being held by William de Radeclive, of the "Radclyffes of the Tower" family.[8]

In the 15th century the Pilkington family, who during the Wars of the Roses supported the House of York, owned much of the land around the parish. Thomas Pilkington was at this time lord of many estates in Lancashire.[17][18] In 1485 Richard III was killed in the Battle of Bosworth. The Duke of Richmond, representing the House of Lancaster, was crowned Henry VII. Sir William Stanley may have placed the crown upon his head. As a reward for the support of his family, on 27 October 1485 Henry made Thomas Stanley the Earl of Derby. Thomas Pilkington was attainted, and in February 1489 Earl Thomas was given many confiscated estates including those of Pilkington, which included the township of Pilkington, and Bury.[18] During the English Civil War Radcliffe, along with nearby Bolton, fought on the side of the Parliamentarians against the Royalist Bury.[19]

In 1561, after about 400 years rule by the Radclyffes, Robert Assheton (Lord of the Manor of Middleton) bought the manor of Radcliffe for 2,000 Marks.[7][20] From 1765 the Assheton estates were divided between the two daughters of the late Ralph Assheton, one of whom married Thomas Egerton, 1st Earl of Wilton. The manor of Radcliffe appears to have been included in her share, and thereafter was included in the Wilton estates.[7]

Textiles and the Industrial Revolution

[edit]

The first documented reference to industry in Radcliffe is after 1680, in the Radcliffe parish registers, which make increasing mention of occupations such as woollen webster (weaving), linen webster, and whitster (bleacher). These were cottage industries which worked alongside local agriculture. In 1780 Robert Peel built the first factory in the town, several hundred yards upstream from Radcliffe Bridge (at the end of Peel Street). With a weir and goit providing motive power for a water wheel, the factory was built for throstle spinning and the weaving of cotton—a relatively new introduction to Britain. The water wheel proved to be insufficient, and so around 1804 the goit was extended. The weir (known as Rectory Weir)[23] was made from timber.[24] Conditions were poor; the mill employed child labour bought from workhouses in Birmingham and London. Children were boarded on an upper floor of the building, and bound until they reached the age of 21. They were unpaid, and were kept locked up each night. Shifts were typically 10–10.5 hours in length, and children returning from a day shift would sleep in the same bed as children leaving for a night shift. Peel himself admitted that conditions at the mill were "very bad".[25] In 1784 an outbreak of typhoid prompted Lord Grey de Wilton to inform the magistrates of the Salford Hundred;[26] keen to prevent the spread of the disease to neighbouring towns and villages, they sent doctors to assess the situation. Their recommendations included leaving the windows of the mill open at night, fumigation of rooms with tobacco (as this was thought to discourage disease), regular cleaning of rooms and toilets and occasional bathing of children.[27] The report forced the magistrates, led by Thomas Butterworth Bayley, to abandon the practice of binding parish apprentices to any mill not adhering to these conditions. The report also prompted Peel to introduce an Act of Parliament to improve factory hygiene, which later became the Factory Act of 1802.[28][29] Over time, conditions at the mill improved; in the mid-1790s the physician John Aikin, a critic of the factory system, praised working conditions at the mill,[30] and in 1823 inspections by local magistrates of conditions in mills across the county revealed that unlike many others, the factory at Radcliffe was adhering to all requirements of the Factory Acts.[31]

The underlying coal measures throughout the parish were a valuable source of fuel. Radcliffe already had an established textile industry before the arrival of steam power. The first recorded instance of coal getting in the North West of England was in 1246, when Adam de Radeclyve was fined for digging de minera on common land in the Radcliffe area. Coal outcroppings were not uncommon; as recently as 1936 members of the public were seen carrying away large pieces of coal from a seam revealed by the landslip caused when the Manchester Bolton & Bury Canal breached at Ladyshore. Mining was initially limited to bell pits until the arrival of steam engines, which along with improved ventilation, made possible much deeper pits. The earliest known local use of such an engine was in 1792 at Black Cat Colliery. The parish of Radcliffe was once home to as many as 50 pits, but with the exceptions of Outwood Colliery and Ladyshore Colliery, all were either exhausted or closed by the end of the 19th century. During the 1926 General Strike many striking miners illegally took coal from exposed seams around the Coney Green area of the town, to sell to local housewives. In the 1950s to the north of the town the National Coal Board did some open cast mining near Radcliffe Moor Road, but the last legal instance of coal mining in Radcliffe was between 1931 and 1949, close to Bury and Bolton Road.[32]

The transformation of the area from an industry based upon water power, to one based upon steam power, may not have been without problems. A story in W. Nicholl's History and Traditions of Radcliffe (1900) tells of a "great crowd" of protesters from Bury who marched on Bealey's Works, demanding that work be halted. James Booth ordered the gates closed, gave the ringleaders £5, and promised to halt work the next day. The crowd then marched on other businesses within the town before heading along the canal to Bolton, at which point they were apparently turned back by news of approaching soldiers.[33]

There were many smaller textile concerns in the parish. Thomas Howarth owned a cottage in Stand Lane from where he sent yarn to be dyed and sized. He made his own warps which were weaved in the town. He would then travel to Preston and Kendal where drapers would purchase his products. His nephews founded A. & J. Hoyle's Mill in Irwell Street, which employed power weaving to produce their specialities in Ginghams and shirting. The mill closed in 1968. Messrs Stott & Pickstone's Top Shop on Stand Lane was the first company to employ powered looms and spinning around 1844. Many of their employees would eventually leave to start their own businesses, such as Spider Mill, built by Robert and William Fletcher, and John Pickstone. This mill closed around 1930.[35]

Radcliffe was at one time home to around 60 textile mills and 15 spinning mills, along with 18 bleachworks of which the Bealey family were prominent owners.[36] However, the textile industry was not the town's major employer; other industries such as mining and paper making were also important sources of employment.[37]

Mount Sion Mill along Sion Street was founded in the early 19th century and during the First World War manufactured guncotton. A weir was constructed along with a goit, used to turn a water wheel which powered a beam engine to pump water to the reservoirs above.[38][39]

Radcliffe became well known for its paper industry; its mills included the East Lancashire Paper Mill and Radcliffe Paper Mill. The former was founded by the Seddon family on 29 March 1860, along the banks of the Irwell. Its construction provided much-needed employment: in the 1860s living standards within the town were poor, and local mills often operated on "short time". A reduction in the demand for coal had placed many colliers out of work, and the Lancashire Cotton Famine was starving Lancashire of raw materials, especially cotton. Soup kitchens were opened by local benefactors, and many local residents were on poor relief.[40] The mill began producing low grade paper and newsprint, moving on to other products including high quality printing and writing papers. Radcliffe Paper Mill was formed during the First World War, when it took over from a paper mill and a pipe plant. It originally produced paper suitable for roofing felt, to cater for a national shortage. After World War II the mill employed over 600 people and produced 70,000 tons of paper annually. British Plaster Board Industries (BPB) took over the company in 1961.[41]

Other industries in the town included brick making and chimney pot manufacture. Raw materials were sourced from local collieries. In Mill Street carts, waggons, and bicycles were manufactured from 1855, and elsewhere motor vehicles were also produced until the late 1950s. John Cockerill moved to the town from Haslingden before leaving for continental Europe to become the founder of Cockerill-Sambre. James Cockerill, employed Radcliffe man William Yates as his manager. Several foundries and machine manufacturers were located around the town, including Dobson and Barlow at Bradley Fold, and Wolstenholme's along Bridgewater Street. Munitions, aircraft and tank components were manufactured during the Second World War. Chemicals were manufactured by companies such as Bealey's and J. & W. Whewell.[42]

Post-industrial history

[edit]From the 1950s Radcliffe's textile industry went into terminal decline, and although its paper industry survived to the end of the 20th century, both the town's largest paper mills have now been closed and demolished.[19] One of the larger mills in Radcliffe was the Pioneer Mill, built between 1905 and 1906, and which ceased weaving in July 1980—the last mill in Radcliffe to use cotton.[22] The building is now occupied by several different businesses.

Although the town retains much of its existing Victorian and Edwardian housing stock, new estates have been built on former brownfield land including that of the Radcliffe Paper Mill Company.[19] Since deindustrialisation the local population has continued to grow.[43] Radcliffe's housing stock of 23,790 properties is a mixture of mainly semi-detached and terraced housing, with smaller percentages of detached housing and flats.[44][45][46][47][48] In 1974 the town became a part of the Metropolitan Borough of Bury, and as a result has been described as losing its independence, and to some extent its identity.[19]

Governance

[edit]

Following the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, Radcliffe formed part of the Bury Poor Law Union, an inter-parish unit established to provide social security.[2] Radcliffe's first local authority was an early form of local government in England. In July 1866 the Radcliffe Local Board of Health was established.[2] With reference to the Local Government Act 1858, it was a regulatory body consisting of 12 members,[50] responsible for standards of hygiene and sanitation in the township. Richard Bealey J.P. was chairman of the local board until April 1876[50] In the same year, the parish was extended to include parts of the former township of Pilkington, formerly in the parish of Prestwich-cum-Oldham.[17]

Radcliffe became a part of the Municipal Borough of Bury in 1876, but following the Local Government Act 1894 it left the district (by then the County Borough of Bury), becoming an urban district within the administrative county of Lancashire.[2][51] The district boundary was extended to include the Stand Lane district[52] The extension made the area covered by Radcliffe Urban District 3,084 acres (12.48 km2; 4.819 sq mi).[50] Radcliffe Urban District was governed by a council of 24 members, made from six councillors from each of the four wards, Radcliffe Hall, Radcliffe Bridge, Black Lane, and Stand Lane.[7] Alker Allen J.P. was the first chairman of the new council.[50] Radcliffe Town Hall was built in 1911, replacing an earlier building on the junction of Water Street and Spring Lane. It formed the public administrative centre for the district with a large council chamber on the first floor, with public gallery, and four committee rooms.[53]

The Lancashire (Southern Areas) Review Order of 1933 extended the district to include the township of Ainsworth, and a portion of the township of Outwood. This increased the area covered by Radcliffe District to 4,915 acres (19.89 km2). A new ward was created for Ainsworth, comprising the former township and a portion of the Black Lane ward. Three councillors were added to the council, and the total number of electors became 15,009.[54] On 21 September 1935 the urban district received a charter as a municipal borough, which gave it borough status, and elevated it to the Municipal Borough of Radcliffe.[55][56]

Under the Local Government Act 1972 the town's urban district status was abolished, and Radcliffe has, since 1 April 1974, formed an unparished area of the Metropolitan Borough of Bury, a local government district of the metropolitan county of Greater Manchester.[2][57][58]

For electoral purposes, Radcliffe is now divided into three wards; Radcliffe North, Radcliffe East, and Radcliffe West.[5] It is in the Bury South constituency and was represented in the House of Commons by Labour Party member Ivan Lewis; however he was suspended from the party in 2017 and sat as an independent until the dissolution of Parliament ahead of the 2019 general election.[59] Since December 2019, the constituency has been represented by Labour Party member Christian Wakeford; Wakeford was elected a Conservative, but defected to Labour in January 2022.

Geography

[edit]

At 53°33′41″N 2°19′36″W / 53.56139°N 2.32667°W (53.5615°, −2.3268°) and 170 miles (274 km) northwest of central London, Radcliffe lies in the Irwell Valley on the course of the River Irwell. The towns of Bury and Bolton lie to the northeast and northwest. For the purposes of the Office for National Statistics, Radcliffe forms a northerly part of the Greater Manchester Urban Area,[61] with Manchester city centre 6.5 miles (10.5 km) to the south-southeast.[62]

Radcliffe's position on the River Irwell has proved important in its history and development as the river provided a source of water for local industry. Radcliffe E'es, a level plain formed along the north bank of the Irwell during the previous ice age,[9] is now derelict and the planned location of a new school.[63] From a highpoint of 500 feet (152 m) above sea level in the northwest of Radcliffe, the surface gradually descends, particularly in the south and east, being the lowest along the River Irwell. The geology is represented by coal measure.[7]

Radcliffe is surrounded by open space and rural land, much of which is visible from the town centre.[19] To the east of the town the River Roch flows under Blackford Bridge, and joins the Irwell shortly thereafter, along which several weirs and goits were built as it passes through the town. Flowing from east to west the river divides the town on the north and south sides of the valley respectively. The town centre sits on the north side of the valley. Two road bridges cross the river: one in the former hamlet of Radcliffe Bridge, and another newer bridge built as part of the A665 Pilkington Bypass. Another bridge crosses the river along the eastern border with Bury. Various smaller pedestrian footbridges and two railway viaducts (one disused) also exist.[64]

Demography

[edit]| Radcliffe compared | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 UK census | Radcliffe[65] | Bury (borough)[66] | England[66] |

| Total population | 34,239 | 180,608 | 49,138,831 |

| White | 96.2% | 93.9% | 91.0% |

| Asian | 2.1% | 4.0% | 4.6% |

| Black | 0.3% | 0.5% | 2.3% |

| Christian | 73.5% | 73.7% | 71.7% |

| Buddhist | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.3% |

| Hindu | 0.4% | 0.4% | 1.1% |

| Jewish | 6.7% | 4.9% | 0.5% |

| Muslim | 1.7% | 3.7% | 3.1% |

| Sikh | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.7% |

| Other religions | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.3% |

| No religion | 10.2% | 10.2% | 14.6% |

| Religion not stated | 7.1% | 6.7% | 7.7% |

According to the Office for National Statistics, at the time of the United Kingdom Census 2001, Radcliffe had a population of 34,239. The population density in 2001 was 9,132 inhabitants per square mile (3,526/km2), with a 100 to 94.9 female–male ratio.[67] Of those over 16 years old, 28.6% were single (never married) and 42.8% married.[68] Radcliffe's 14,036 households included 28.1% one-person, 39.0% married couples living together, 9.2% were co-habiting couples, and 12.3% single parents with their children.[69] The figures for married couples households was below the borough (48.5%) and national average (47.3%), and single parent households were slightly above the average for the whole of Bury (11.6%) and England (10.5%).[70] Of those aged 16–74, 31.1% had no academic qualifications, slightly higher than averages of Bury (29.2%) and England (28.9%).[66][71]

The residential areas of Radcliffe both to the north and the south of the town centre operate as suburbs of Bury and Manchester, such that their populations are not necessarily linked to the town. The socio-demographic characteristics of the town's population includes a mix of working and suburban middle classes, the layout of which are both linked to neighbouring towns.[19]

Radcliffe is within the Manchester larger urban zone,[72] and within the Manchester travel to work area.[73]

Economy

[edit]Radcliffe's first market was built by the Earl of Wilton and opened in 1851.[7] The town was home to twelve Co-op stores,[74] the largest of which was on Stand Lane. The four-storey structure, built in 1877, had shops and offices on the ground floor, and a large area for public meetings on the second floor.[75] The building was truncated to two stories in June 1971, and eventually demolished.[76] Two more Co-op stores were located on Bury Street[77] and Cross Lane.[78] The current market hall, built in 1937 on a different site to the old market, suffered a devastating fire in 1980[79] but was later restored. Radcliffe was once served by several banks including the Lancashire and Yorkshire Bank, the Manchester and Liverpool District Bank, the Union Bank of Manchester, and Parr's Bank ltd.[80] As of 4 May 2019 the Royal Bank of Scotland and Halifax bank have closed or are in the process of closing in the town. The Halifax branch on Blackburn street is to close on 28 May 2019. These closures will leave only the TSB on the Market Place (M26 1PN) as the only bank in the town[81][82][83]

Radcliffe has two weekly newspapers, the Radcliffe Times, based at the Bury Times offices, in Bury,[citation needed] and the Salford-based The Advertiser, which also covers the neighbouring areas of Prestwich and Whitefield.[84] The main gates to the East Lancashire Paper mill (mill closed in 2001) were, in May 2018, installed in the centre of Radcliffe's Festival Gardens[85] off Church Street.[86]

The construction in the 1980s of the A665 Pilkington Way Bypass relieved traffic congestion along the traditional route through the town, Blackburn Street. A new bridge across the Irwell was constructed for the road, and part of Blackburn Street was pedestrianised. The road has attracted developments along former industrial land to the west of the town, including a large Asda superstore and petrol filling station which opened in May 1997, when Asda moved out of their town centre store in Green Street, although it has exacerbated the decline of the retail outlets in the town centre. The bypass has created problems for cyclists and pedestrians who appear reluctant to cross the road and visit the town centre.[87][88] One solution presently under consideration would involve a partial reopening of the pedestrianised section of Blackburn Street to traffic.[87]

The closure of the East Lancashire and Radcliffe Paper Mills, both of which employed thousands of people, has left a large gap in the town's local economy.[19] Along with the decline of local industry the town's shopping centre has suffered a severe loss of trade and is now barely viable as a retail outlet. Radcliffe's market hall compares poorly with the neighbouring Bury Market.[88] Amongst other shops, the town's central shopping precinct retains a Boots.[89] A Dunelm Group, formerly known as Dunelm Mill, home and soft furnishings store now occupies the former site of the town's Asda supermarket on Green Street.[90] In February 2018 a new Lidl store opened its doors on the site of the old bus station employing around forty people.[91]

"Re-inventing Radcliffe" is the name given on a report of a proposed improvement scheme. The report envisages several initiatives, and includes the creation of new housing both to the north and south of the town. Existing industry to the west of the town and along Milltown Street would be retained and improved, along with sections of the former Radcliffe Paper Mill and Pioneer Mill. The market would be redeveloped along with the Kwik Save site and bus station, and the town could become a centre for the arts. To improve transport links, new crossings of the Irwell and canal are proposed. Plans for a new secondary school in Radcliffe are now in doubt, however a new build at Castlebrook High School Parr Lane, Bury BL9 8LP began in January.[92] Finally, the report suggests improving the image of Radcliffe within the Bury area.[4] On 27 June 2018, due to very hot weather, a fire started on the exterior of the complex of shops adjoining the precinct as roofing tar caught alight.

"Newlands" is a regeneration programme run by the Forestry Commission.[93] One site under consideration for regeneration is the former waste tip of Radcliffe E'es.[94]

Population and employment change

[edit]| Population growth in Radcliffe from 1801 to 2001 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1801 | 1811 | 1821 | 1831 | 1841 | 1851 | 1861 | |

| Population | 2,497 | 2,792 | 3,089 | 3,904 | 5,099 | 6,293 | 8,838 | |

| Year | 1871 | 1881 | 1891 | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | |

| Population | 11,446 | 16,267 | 20,021 | 25,368 | 26,084 | 24,759 | 24,675 | |

| Year | 1939 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | |

| Population | 26,951 | 27,556 | 26,726 | 29,274 | 27,642 | 32,567 | 34,239 | |

| Ancient Parish 1801–1891[95] • Urban District 1901–1931[96] • Municipal Borough 1939–1971[96] • Urban Subdivision 1981–2001[97][98][99] | ||||||||

In 1921 2,394 men and 3,680 women were employed in the textile industry.[100] By 1951 these figures had fallen respectively to 981 and 1,852.[101] A more drastic fall is evident in the numbers of people employed in the mining and quarrying industries; in 1921 591 people were employed in both,[100] but in 1951 this had dropped to only 57,[101] reflecting the number of mines in and around Radcliffe that had by that time been completely exhausted.[32]

By 2001, from a working population of 15,972 between the ages of 16–74 only six people were employed in mining. 3,011 people were employed in manufacturing, 103 in public utilities, and 985 in construction. 3,371 people worked in wholesale and retailing; repair of motor vehicles, 682 in hotels and catering, and 1,185 in transport; storage and communication. 642 people worked in financial intermediation, 1,711 in real estate, 694 in public administration and defence, 987 in education, 1,876 in health and social work, and 657 in other work.[102]

Landmarks

[edit]

Radcliffe Tower is all that remains of an early 15th-century stone-built manor house. The structure is a Grade I listed building and protected as a Scheduled Monument.[103][104] The construction of a nearby tithe barn is not documented, but it was probably built between 1600 and 1720.[105] It was used for storage of the local tithes (a tenth of a farm's produce).[106] Along with Radcliffe Tower, the Parish Church of St Mary is a Grade I listed building.[107] The town also has two Grade II* listed buildings; Dearden Fold Farmhouse, completed during the 16th century,[108] and Radcliffe Cenotaph, built in 1922 to commemorate the First World War.[109] Outwood Viaduct, and Radcliffe's most visible landmark, St Thomas' Church, are Grade II listed buildings.[110] St Thomas' took nine years to complete. The first stone was laid by Viscount Grey de Wilton (grandson of the Countess Grosvenor) on 21 July 1862, and it was consecrated in 1864 by the first Bishop of Manchester, James Prince Lee. Construction of the tower began in 1870[111] and the building was completed in 1871. The building cost £7,273,[40] (£860,000 today)[112] and the tower cost £1,800 (£210,000 today).[112] The first vicar was the Reverend Robert Fletcher.

Radcliffe's first public ornament was a drinking fountain located at the bottom of Radcliffe New Road. It was presented to the town by a Mrs Noah Rostron in memory of her husband, and erected in August 1896.[113] The fountain no longer exists at this location.

Built in 1911 the town hall was on the junction of Water Street and Spring Lane.[56] For many years after the town lost its urban district status, the building was unoccupied. It was converted to private accommodation in 1999.[114]

Transport

[edit]The Manchester to Blackburn packhorse route passed through the town (hence the name Blackburn Street). The bridge across the Irwell was likely first erected during the late Medieval period at the site of a ford. An Act of Parliament in 1754 authorised the first turnpike through the hamlet of Radcliffe Bridge,[115] and included Manchester to Bury via Crumpsall, and from Prestwich to Radcliffe. An Act of 1821 created a turnpike from Bury to Radcliffe, Stoneclough and Bolton. An Act of 1836 created a turnpike from Starling Lane to Ainsworth, and Radcliffe to Bury and Manchester Road (near Fletcher Fold). A turnpike from Whitefield to Radcliffe Bridge via Stand Lane was created in 1857 with toll houses at Besses o' th' Barn, Stand Lane, the junction of Dumers Lane and Manchester Road, on Bolton Road near Countess Lane, and on Radcliffe Moor Road at Bradley Fold. Radcliffe New Road was created in an Act of 1860 which enabled the construction of a toll road between Radcliffe and Whitefield.[116] To prevent damage to the road surfaces, weighing machines were used at various strategic positions including at the bridge end of Dumers Lane, at Sandiford turning, and on Ainsworth Road.[117][118]

During the Industrial Revolution, as local cottage industries were gradually supplanted by the factory system the roads became inadequate for use. A convoy of horse-drawn lorries carrying salt between Bealey's Bleach Works and Northwich would take up to two weeks to make a return journey.[116] These problems gave rise to the construction of the Manchester Bolton & Bury Canal, which reached the town in 1796 and which was navigable throughout in 1808. For 38 years the canal was the town's main route for trade and transport, with a wharf near Hampson Street. The proprietors later converted into a railway company and built a line between Salford and Bolton, which opened in 1838. A branch from this line was to have been built to Bury, along the line of the canal, but due to technical constraints this did not happen.[119] Radcliffe's closest railway connection therefore remained several miles distant at Stoneclough.[23]

The opening of the Manchester, Bury and Rossendale Railway (later known as the East Lancashire Railway (ELR)) in 1846[120] brought the town a direct connection to Manchester and Bury. Two stations served the town, Radcliffe Bridge station, and Withins Lane station (although this closed in 1851 after only a few years of operation). Ringley Road station was located to the south of the parish, close to the civil parish of Pilkington. The line crossed the Irwell over Outwood Viaduct, an impressive structure which remains to this day.[121]

The Liverpool and Bury Railway (L&BR) opened on 28 November 1848, with a station to the north of the town, called Black Lane station. On 18 July 1872 the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (L&YR), which had amalgamated with the ELR some years previously, gained an Act of Parliament to construct a railway between Manchester and Bury, via Whitefield and Prestwich. This opened in 1879 with a new station, known as Radcliffe New Station,[122] with a link to the L&BR line at Bradley Fold (near the present day Chatsworth Road), and a new station along Ainsworth Road, Ainsworth Road Halt. The new L&YR route joined the existing ELR route near Withins Lane (North Junction), whereon they shared the connection to Bury. The L&YR gained a further act, the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Act 1877 (40 & 41 Vict. c. lix), to construct a link between North Junction and Coney Green Farm (West Junction). The LY&R line was electrified in 1916 for which a substation was constructed, between the canal and the West Fork.[115]

The town also had an extensive tram network. The first tram ran from Black Lane (latterly Ainsworth Road) in 1905, with a terminus next to St Andrew's Church on Black Lane Bridge. In 1907 a branch was built to connect to the Bury to Bolton part of the network.[123] A large bus station is located between Dale Street and the river.[124] Officially abandoned in 1961, the canal is currently undergoing restoration on the Salford arm,[125] although a rebuilt bridge along Water Street presents a barrier to its full restoration.[126]

Public transport in Radcliffe is now coordinated by Transport for Greater Manchester (TfGM), a county-wide public body with direct operational responsibilities such as supporting (and in some cases running) local bus services, and managing integrated ticketing in Greater Manchester.

The town is now served only by a single light rail system and regular bus services.[124] The Metrolink opened on 6 April 1992 along the L&YR line between Manchester and Bury/Bury and Altrincham (Manchester also serves as a change point for the rest of the Metrolink system as it expands to cover a greater portion of the region, including Oldham).[127] Trams leave from the town's station every six minutes between 7:15 am and 6:30 pm, and every 12 minutes at other times of the day.[128] Radcliffe Bridge station closed on 5 July 1958,[129] and has since been replaced by the path of the A665 Pilkington Way (the new road has been built below the level of the old station).[64] The path of the ELR line is still quite visible from aerial photography, with Outwood Viaduct fully restored,[130] and the route of the line southwest of the town converted for use as a nature trail forming part of the Irwell Sculpture Trail.[131]

National Cycle Route 6 runs through the town, along the route of the former ELR line, through the town centre and continuing toward Bury along the Manchester, Bolton and Bury Canal.[132] New combined pedestrian and cycle crossings have been constructed to facilitate the route.[133] A new cycleway has also been built along the line of the former Liverpool to Bury Railway, to the north of the town.[134]

Education

[edit]

One of the earliest schools in the parish was the Close Wesleyan Day School, a Dame school opened around 1840.[135] St Thomas's day school was opened on 4 March 1861, and housed over 500 children. Due to overcrowding and the risk of subsidence caused by local mining activity, the school was rebuilt on a new site along School Street, provided by the Earl of Wilton. It was opened in October 1877 by Lady Wilton. On the opposite side of the town St John's school started life in 1860 as an institute along Irwell Street, and by 1864 contained 120 children. The buildings were enlarged in 1869. In 1897 eight teachers and a monitor taught 358 children. In 1899 the school leaving age was twelve, and many of the senior class were "half-timers" who would spend half the day at school, and the other half at work. This system was abolished in 1919. Regular epidemics of scarlet fever, chicken pox, mumps, and especially measles, meant that in 1897 and 1903 the school was temporarily closed.[136] St John's School and the nearby church were demolished in the 1970s.[137] Radcliffe also had a technical school on Whittaker Street. Formally opened by Lord Stanley on 7 November 1896, it adjoined the public baths on Whittaker Street.[138] The building is now used as council offices.[139]

Radcliffe County Secondary School was founded in 1933[140] on the former Peel Park Ground near School Street, but Radcliffe's first secondary school (apart from an endowed grammar school in nearby Stand) was held at the New Jerusalem schoolroom from the early 1860s.[141] Radcliffe East, latterly known as Coney Green County Comprehensive School, was built in 1975 on the site of the former railway goods yard alongside Radcliffe East Fork. Part of the school, known as "Phase One", opened in September 1975, with 150 first-year pupils, and 70 second-year pupils (from Radcliffe County Secondary School). The remainder, known as "Phase Two", opened two years later.[142]

Radcliffe has ten primary schools, but no secondary schools. A new school was proposed to replace the former Coney Green and Radcliffe High schools,[4] but recent developments make the construction of this school uncertain.[143]

Religious sites

[edit]

In Romano–British times, Radcliffe was in the Diocese of York; in Saxon times in the Diocese of Lindesfarne, then of York; in Norman times in the Diocese of Lichfield; after 1540 in the Diocese of Chester and since 1847 in the Diocese of Manchester.[144]

Based on the subdivisions of the dioceses, before 1535[145] Radcliffe ancient parish was in Manchester and Blackburn Rural Deanery. Between this date and 1850 the ancient parish was placed in Manchester Rural Deanery. From 1850 to 1851 it was placed in Bury Rural Deanery; from 1851 to 1872 it was in Prestwich Rural Deanery; from 1872 to 1912, it was placed in Prestwich and Middleton Rural Deanery; and since 1872 it has been in Radcliffe and Prestwich Rural Deanery.[146]

Church of England

[edit]Radcliffe was an ancient parish which in its early history had duties which combined both ecclesiastical and civil matters. In 1821 Radcliffe St. Thomas ecclesiastical parish was created from the ancient parish, and it was re-founded in 1839. In 1873 further parts of the ancient parish were taken to form Bury St. Peter's ecclesiastical parish. In 1878 parts of the ancient parish as well as part of Radcliffe St. Thomas were taken to form Radcliffe St. Andrew, Black Lane ecclesiastical parish.[146] The Parish Church of St Mary was built during the 14th century, and the tower added in the 15th century. In 1966 it was designated a Grade I listed building by English Heritage under its former name of the Church of St Mary and St Bartholomew.[107] In 1991 some local parishes were merged, and the church adopted its present name.[147]

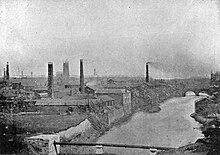

Radcliffe is also served by the Parish of St Thomas and St John. St Thomas' is visible on the horizon for many miles. The original church was built in 1819 by Countess Grosvenor[40] and is visible above in the image of Radcliffe Bridge. The building was later considered too small, and in 1862 was demolished and replaced with the present structure (see landmarks). The Church of St John was consecrated on 19 February 1866 at the bottom of Radcliffe New Road. Built at a cost of about £4,000 (£470,000 today)[112] the site was donated to the church by the Earl of Derby, who in 1897 also made a grant of land for the site of the Mission Church at Chapelfield.[148] The parishes of St John and St Philip were merged with St Thomas' in 1975–76.[137][149] Radcliffe is also home to the Church of St Andrew on Ainsworth Road, which was consecrated in 1877.[150]

Other faiths

[edit]Radcliffe was also home to many smaller churches. The main Roman Catholic church, St. Mary & St. Philip Neri, on Spring Lane, was built in 1894.[151] In 2009 a new Catholic Church of the same name was opened (29 May 2009) in a brand new purpose built building on Belgrave street in Radcliffe.[152] The old St Mary's Church on Spring Lane has since been demolished. Other churches included Stand Independent, a Quaker meeting house on Foundry Street, Water Lane Congregational, and several Wesleyan churches, including one on Bridgefield Street, which in March 2008 was destroyed by fire.[153] The church was built in 1892.[154] The United Reformed Church has two congregations within the town, one on Lord Street, and the other on Stand Lane. The church was originally formed from a Congregational school in 1848.[155] A Methodist New Connexion church has existed along Smyrna Street since 1844.[156] Other faiths are also catered for, with a mosque on Bridgefield Street,[157] and a centre and a church for Swedenborgianism on Radcliffe New Road and Stand Lane respectively.[158]

Sports

[edit]Radcliffe has a rich history of sport, including football, rugby, cricket and swimming, but entertainment in Radcliffe once included bear-baiting, bull-baiting, and cock-fighting. Cock fights were prevalent in the town and took place in local "hush-shops", generally viewed by invitation only. Bull and bear baiting was held in the Radcliffe Bridge area of the parish. In Nicholls' History and Traditions of Radcliffe (1900) the author describes the contents of the diary of a Lord Kenyon, who wrote "W.M. Robt. James, and Thomas Radcliffe, were fined for causing a Bayre to be bayted upon Saturday being the 18th of March 1587–8, at the Bull-Ringe neere the conduite in Manchester."[159] Trained dogs were used to attack a bull, which was donated by the Earl of Wilton. Such entertainment took place where the bridge now stands, along the banks of the river near the ford. Such spectacles were eventually outlawed by Act of Parliament, and the last bull bait in the town was held on 26 September 1838. Horse racing replaced the sport the following year, with a course alongside the river. During the first year of racing the main spectator stand collapsed, injuring many spectators. In 1876 events were moved to a new course[159] approximately one mile in circumference[160] at Radcliffe Moor, upon which site the town's cricket club now stands.[159]

The town is home to the Greater Manchester Cricket League side Radcliffe Cricket Club, who played in the Central Lancashire Cricket League until its demise in 2015. For many years Sir Frank Worrell played for the club,[161] and a street near the cricket ground was named in his honour.[162] Sir Garfield Sobers joined the club in 1958 at the age of 21.[161] The town also has two Football teams, Radcliffe Town,[163] and Radcliffe F.C. (formerly Radcliffe Borough). The football club Bury A.F.C. groundshared with Radcliffe F.C. at Stainton Park until the former's merger with Bury F.C. Former players include Paul Gascoigne,[164] Craig Dawson[165] and Matt Derbyshire.[166]

Radcliffe was also home to Nellie Halstead,[167] who in her time was known as "Britain's greatest woman athlete". A multiple world record holder, she represented Great Britain at the 1932 Olympic Games in Los Angeles.[168]

Public services

[edit]

History

[edit]The Rivers Pollution Prevention Act 1876 posed a problem for the local authorities; disposal of sewage was generally an expensive proposition, and efforts to resolve the practical problems involved were often unsatisfactory. After initial experiments, in 1894 contracts were let for work. Chairman of the Local Board Samuel Walker Esq cut the first sod on 23 April 1894, and the works were completed in the following year.[170]

The town was provided with electricity by a coal-fired power station along the south bank of the river, to the west of the town. Authorised by the Radcliffe Electric Lighting Order of 1894, and inaugurated on 5 October 1904,[171] Radcliffe Power Station was opened by the Earl of Derby on 9 October 1905.[172] It originally had two 1,500 kW turbo sets made by British Thomson-Houston, and was the first power station in the country to transmit electricity over bare electrical conductors.[173]

In 1921 the Radcliffe and Little Lever Joint Gas Board purchased the Radcliffe & Pilkington Gas Company. Constituted in 1921 by an Act of Parliament, the board consisted of six members of the Radcliffe Council and one member of the Little Lever Council. The area supplied included all the districts of Radcliffe and Little Lever, and also Prestwich, Whitefield, Unsworth, Outwood, and Ainsworth. In 1935 the company supplied 263,000,000 cubic feet (7,400,000 m3) of gas to 16,748 consumers, and provided gas for public street lighting. Water supplies were provided both by upland watersheds and by the Bury & District Joint Water Board, of which Radcliffe was a constituent authority.[174]

By 1935 a fire brigade and ambulances were available to protect the town during emergencies. The Gamewell system of fire alarms was used and consisted of 16 alarm boxes spread throughout the district. Three motor ambulances and a motorised utility van were kept at the fire station, operated by permanent staff.[175]

Modern services

[edit]The North West Ambulance Service provides emergency patient transport, and the statutory emergency fire and rescue service is now provided by the Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service.[176]

Home Office policing in Radcliffe is provided by the Greater Manchester Police. The Radcliffe police station that was situated along Railway street was closed due to cost saving measures announced by Greater Manchester Police in November 2015. In July 2016 the building was sold by auction to an anonymous buyer for £150,000.[177] Waste management is coordinated by the local authority via the Greater Manchester Waste Disposal Authority.[178] Radcliffe's distribution network operator for electricity is United Utilities.[179]

Notable people

[edit]Born in Radcliffe, the First World War veteran Private James Hutchinson was a recipient of the Victoria Cross.[180] Radcliffe was also the birthplace of Canadian author Donald Jack[181] and the home of Olympic Medal-winning cyclist Harry Hill who took bronze at the 1936 Summer Olympics.[182][183] Nellie Halstead was a runner who represented Great Britain in both the 1932 Summer Olympics and 1936 Summer Olympics.[184] Radcliffe was the birthplace of Oscar-winning film director Danny Boyle[185] and the three times World Champion snooker player John Spencer.[186]

Culture

[edit]

Radcliffe's wealth as a mill town gave rise to many outlets for the entertainment of its population. These included cinemas and public houses. Several cinemas were built in the town, including the Picturedrome in Water Street,[74] and an Odeon cinema, built in 1937 along Dale Street.[187] Whittaker Street public baths were built in 1898 and demolished in 1971.[188] The swimming pool on Green Street which replaced the old Whittaker Street baths was itself closed down after storm damaged the main facilities in 2013 disclosing high levels of asbestos in the building super-structure. As a replacement a new £945,000 25-metre length modular above-ground swimming pool was erected in 2015 at the recently closed Riverside High School on Spring Lane (formally Coney Green High School). The pool complex also includes a fully equipped public gymnasium. A public library was opened in 1907[189] on a site donated by Andrew Carnegie, who also contributed £5,000 (£670,000 today)[112] towards the cost of the building. Two branch libraries were opened in Ainsworth between 1933 and 1935.[53] A museum was located in the upper rooms of Close House before it was demolished in March 1969.[190]

Radcliffe Brass Band has performed in the town since 1914, when it accompanied one of the Whit Walks that used to take place on Whit Friday.[191] Popular as these were, support later dwindled to a point where they were abandoned around 1977.[192] Rushcart processions were once popular, held on the first Saturday of September, finishing on the following Sunday at the Parish Church.[193]

The town has several parks, including Coronation Park near Radcliffe Bridge and Close Park near Radcliffe Tower. Much of the land for Coronation Park was in 1900 donated by the Earl of Derby. Close House and the grounds around it were formerly the home of the Bealey family, and were donated by the Bleachers' Association.[53] The town is also along the route of the Irwell Sculpture Trail.[131]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ a b "Bury Wards population 2011". Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Greater Manchester Gazetteer, Greater Manchester County Record Office, Places names – O to R, archived from the original on 18 July 2011, retrieved 17 October 2008

- ^ a b McNeil & Nevell 2000, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b c Re-inventing Radcliffe Report, Bury Metropolitan Borough Council, September 2003, archived from the original on 20 October 2007, retrieved 26 October 2008

- ^ a b c Radcliffe Local Area Partnership, Bury Metropolitan Borough Council, archived from the original on 28 October 2010, retrieved 26 October 2008

- ^ Mills 1998, p. 292.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Farrer & Brownbill 1911c, pp. 56–67.

- ^ a b c d Sunderland 1995, p. 15.

- ^ a b Sunderland 1995, p. 10.

- ^ Sunderland 1995, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Although the Sunderland book mentions that this axe is kept at Bury Museum, the Museum has been unable to verify this, but it does possess three axe-hammers of indeterminate origin.

- ^ Bury Archaeological Project, Bury Metropolitan Borough Council, archived from the original on 9 January 2009, retrieved 9 February 2009

- ^ Simpson 1852, p. 98.

- ^ Roman Roads in Lancashire, Lancashire County Council, archived from the original on 8 April 2008, retrieved 26 October 2008

- ^ Sunderland 1995, p. 11.

- ^ Farrer & Brownbill 1911a, pp. 171–173.

- ^ a b Farrer & Brownbill 1911b, pp. 88–92.

- ^ a b Coward 1983, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b c d e f g The Renaissance of Radcliffe – Part 1 (PDF), Bury Metropolitan Borough Council, archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2010, retrieved 4 November 2008

- ^ Sunderland 1995, p. 17.

- ^ Smith 1981, p. 19.

- ^ a b Sunderland 1995, p. 66.

- ^ a b Radcliffe, Lancashire & Furness & Stoneclough, Lancashire & Furness, Ordnance Survey, 1848, retrieved 3 January 2009

- ^ Nicholls 1900, p. 164.

- ^ Augusta & Ramsay 1969, p. 5.

- ^ Landau 2002, p. 238.

- ^ Meiklejohn, A. (16 January 1959), "Outbreak of Fever in Cotton Mills at Radcliffe, 1784", British Journal of Industrial Medicine, 16 (1): 68–69, doi:10.1136/oem.16.1.68, PMC 1037863

- ^ Sunderland 1995, p. 65.

- ^ Russell 2001, p. 86.

- ^ Landau 2002, p. 248.

- ^ Augusta & Ramsay 1969, p. 73.

- ^ a b Sunderland 1995, pp. 83–85.

- ^ Nicholls 1900, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Historic England. "Water Powered Beam Pump (1393833)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- ^ Sunderland 1995, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Sunderland 1995, p. 67.

- ^ Sunderland 1995, p. 68.

- ^ This engine was mentioned in Sunderland's Book of Radcliffe (1995) as existing at the time of publication.

- ^ Sunderland 1995, p. 73.

- ^ a b c Gooderson 1985, p. 8.

- ^ Sunderland 1995, p. 74.

- ^ Sunderland 1995, pp. 78–79.

- ^ see Population and employment change

- ^ Household Spaces and Accommodation Type (KS16), Radcliffe Central Ward, Statistics.gov.uk, 9 November 2004, retrieved 19 January 2009

- ^ Household Spaces and Accommodation Type (KS16), Radcliffe East Ward, Statistics.gov.uk, 9 November 2004, retrieved 19 January 2009

- ^ Household Spaces and Accommodation Type (KS16), Radcliffe North Ward, Statistics.gov.uk, 9 November 2004, retrieved 19 January 2009

- ^ Household Spaces and Accommodation Type (KS16), Radcliffe South Ward, Statistics.gov.uk, 9 November 2004, retrieved 19 January 2009

- ^ Household Spaces and Accommodation Type (KS16), Radcliffe West Ward, Statistics.gov.uk, 9 November 2004, retrieved 19 January 2009[permanent dead link]

- ^ Borough of Radcliffe 1935, p. 0.

- ^ a b c d Borough of Radcliffe 1935, p. 10.

- ^ Youngs 1991, pp. 195, 679, 680, 689.

- ^ This district was formerly within the Whitefield Local Board district.

- ^ a b c Borough of Radcliffe 1935, p. 26.

- ^ Borough of Radcliffe 1935, p. 14.

- ^ Relationships / unit history of Radcliffe, Department of Geography, University of Portsmouth, archived from the original on 30 September 2007, retrieved 5 August 2007

- ^ a b Hudson 2001, p. 110.

- ^ HMSO. Local Government Act 1972. 1972 c. 70.

- ^ Youngs 1991, p. 668.

- ^ Alphabetical List of Members of Parliament, Office of Public Sector Information, archived from the original on 22 August 2008, retrieved 3 November 2008

- ^ Historic weir falls victim to flooding, theboltonnews.co.uk, 13 July 2012, retrieved 6 August 2012

- ^ Office for National Statistics (2001), Census 2001:Key Statistics for urban areas in the North; Map 3 (PDF), statistics.gov.uk, archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009, retrieved 14 October 2008

- ^ Ordnance Survey. (1983), Landranger 109: Manchester & surrounding area (5th ed.), Ordnance Survey, ISBN 0-319-22109-1

- ^ East Lancashire Paper Mill, Bury Metropolitan Borough Council, archived from the original on 10 October 2011, retrieved 23 January 2012

- ^ a b OS Landranger Map sheet 109, Ordnance Survey, archived from the original on 12 November 2008, retrieved 31 December 2008

- ^ "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS06 Ethnic group

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 29 October 2008

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 29 October 2008

- ^ a b c Bury Metropolitan Borough key statistics, Statistics.gov.uk, retrieved 23 January 2012[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS01 Usual resident population

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 29 October 2008

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 29 October 2008

- ^ "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS04 Marital status

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 29 October 2008

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 29 October 2008

- ^ "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS20 Household composition

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 29 October 2008

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 29 October 2008

- ^ Area: Bury (Local Authority): Household type, Statistics.gov.uk, archived from the original on 11 May 2012, retrieved 23 January 2012

- ^ "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS13 Qualifications and students

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 29 October 2008

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 29 October 2008

- ^ Towards a Common Standard (PDF), Greater London Authority, p. 29, archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008, retrieved 5 October 2008

- ^ Travel to Work Areas, Office for National Statistics, archived from the original on 1 October 2008, retrieved 24 September 2008

- ^ a b Hudson 2001, p. 39.

- ^ Radcliffe Parish, Salford Hundred, retrieved 26 October 2008

- ^ Sunderland 1995, p. 48.

- ^ Hudson 2001, p. 33.

- ^ Hudson 2001, p. 35.

- ^ Hudson 2001, pp. 47–49.

- ^ Anon 1905, p. 65.

- ^ "Halifax branch review" (PDF).

- ^ RBS branch finder, rbs.co.uk, retrieved 17 February 2009

- ^ Halifax Bank branch finder, multimap.com, retrieved 17 February 2009

- ^ Manchester local press, Manchesteronline.co.uk, archived from the original on 25 March 2008, retrieved 20 January 2009

- ^ "Radcliffe, Festival Gardens © David Dixon". www.geograph.org.uk.

- ^ "East Lancashire Paper Mill gates preserved and installed at park". Bury Times.

- ^ a b Part 7 – Access to the town centre, Bury Metropolitan Borough Council, archived from the original on 4 June 2015, retrieved 23 January 2012

- ^ a b Part 8 – SWOT Analysis, Bury Metropolitan Borough Council, archived from the original on 4 June 2015, retrieved 23 January 2012

- ^ Boots Manchester Radcliffe, Boots, retrieved 23 January 2012

- ^ Store Locater, dunelm-mill.com, retrieved 21 December 2008

- ^ "New Lidl to open in Radcliffe". Bury Times.

- ^ "Work starts on Castlebrook High School's new £12 million site". Bury Times.

- ^ Newlands, The Forestry Commission, archived from the original on 2 December 2008, retrieved 21 November 2008

- ^ Newlands / Rhodes Farm and Radcliffe Ees, Bury.gov.uk, archived from the original on 9 January 2009, retrieved 23 December 2008

- ^ Radcliffe AP/CP: Total Population, Vision of Britain, retrieved 6 December 2008

- ^ a b Radcliffe MB/UD: Total Population, Vision of Britain, retrieved 6 December 2008

- ^ 1981 Key Statistics for Urban Areas GB Table 1, Office for National Statistics, 1981

- ^ Greater Manchester Urban Area 1991 Census, National Statistics, archived from the original on 5 February 2009, retrieved 24 July 2008

- ^ "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS01 Usual resident population

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 24 July 2008

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 24 July 2008

- ^ a b Radcliffe MB/UD: Persons of Working Age by Sex and 1921 Occupational Order, A Vision of Britain through Time, Standardised Industry data, retrieved 29 October 2008

- ^ a b Radcliffe MB/UD: Persons of Working Age by Sex and 1951 Occupational Order, A Vision of Britain through Time, Standardised Industry data, retrieved 29 October 2008

- ^ "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS11a Industry of employment – all people

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 7 December 2008

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 7 December 2008

- ^ Historic England, "Radcliffe Tower (44210)", Research records (formerly PastScape), retrieved 5 January 2008

- ^ Historic England, "Radcliffe Tower (1309271)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 5 January 2008

- ^ Historic England, "Tithe barn (44213)", Research records (formerly PastScape), retrieved 12 December 2008

- ^ Darvill 2003, p. 433.

- ^ a b Historic England, "Church of St Mary and St Bartholomew (1163125)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 23 December 2007

- ^ Historic England, "Dearden Fold Farmhouse (1356793)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 23 February 2008

- ^ Historic England, "Radcliffe Cenotaph (1067192)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 23 February 2008

- ^ What to do or visit: Radcliffe, Bury Metropolitan Borough Council, retrieved 28 October 2008[dead link]

- ^ Gooderson 1985, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Swinburne, Rev. Stanley, Radcliffe Historical Almanack, Bury Library, Local Studies: unknown, p. 4

- ^ Radcliffe Town Hall, The Housing Link, 2003, archived from the original on 11 September 2011, retrieved 13 November 2007

- ^ a b Wells 1995, pp. 102–103.

- ^ a b Sunderland 1995, p. 53.

- ^ Nicholls 1900, pp. 108, 111.

- ^ Records of Prestwich, Bury and Radcliffe Turnpike Trust, Bury Archives Service, Moss Street, Bury: Bury Archives Catalogue, archived from the original on 11 August 2011, retrieved 28 October 2008

- ^ Wells 1995, p. 3.

- ^ Wells 1995, p. 4.

- ^ Wells 1995, pp. 109–115.

- ^ From 1933 this station was renamed "Radcliffe Central"

- ^ Sunderland 1995, p. 43.

- ^ a b Radcliffe Bus Station (PDF), GMPTE, 9 June 2008, archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2007, retrieved 1 January 2009

- ^ Full Steam Ahead For Canal Restoration in Salford, British Waterways, retrieved 27 June 2008

- ^ History of the Waterway – Restoration, Manchester Bolton & Bury Canal Society, archived from the original on 10 October 2008, retrieved 12 December 2008

- ^ Simpson 1994, p. 57.

- ^ Tram Times, Metrolink, archived from the original on 17 December 2008, retrieved 1 January 2009

- ^ Wells 1995, p. 114.

- ^ Outwood Viaduct Restoration, Bury Metropolitan Borough Council, archived from the original on 10 June 2015, retrieved 23 January 2012

- ^ a b Bury's Irwell Sculpture Trail (PDF), irwellsculpturetrail.co.uk, archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009, retrieved 1 January 2009

- ^ Route 6, sustrans.org.uk, retrieved 27 October 2019

- ^ Radcliffe goes cycle-friendly, tfgm.com, 30 October 2017, retrieved 27 October 2019

- ^ Bury Bolton railway path, bury.gov.uk, retrieved 27 October 2019

- ^ Nicholls 1900, p. 30.

- ^ Gooderson 1985, pp. 62–63.

- ^ a b History of St Thomas' Church, St Thomas and St John, retrieved 23 January 2012

- ^ Nicholls 1900, p. 255.

- ^ Buildings in Radcliffe, Bury Metropolitan Borough Council, archived from the original on 7 December 2008, retrieved 12 December 2008

- ^ Radcliffe High School Prospectus, Bury Library, Local Studies, r25.21(P), 1992

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Nicholls 1900, p. 306.

- ^ Waller, Andrew (12 June 1975), "School will be a vital part of the community", Radcliffe Times, p. 11

- ^ "Riverside row rages on", Bury Times, 6 November 2008, retrieved 22 November 2008

- ^ Radcliffe Parish Church History, Radcliffe Parish Church, archived from the original on 20 November 2008, retrieved 16 November 2008

- ^ The exact date is unknown.

- ^ a b Youngs 1991, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Radcliffe Parish Church, Radcliffe Parish Church, archived from the original on 17 March 2007, retrieved 14 January 2008

- ^ Anon 1905, p. 20.

- ^ Both these churches were later demolished

- ^ Anon 1905, p. 21.

- ^ Parish History, radcliffecatholic.org, retrieved 23 January 2012

- ^ "St Mary & St Philip Neri". taking-stock.org.uk.

- ^ "Inquiry as church wrecked by fire", BBC News, 20 March 2008, retrieved 16 November 2008

- ^ Loss and Hope in Radcliffe, The Methodist Church of Great Britain, archived from the original on 6 June 2011, retrieved 16 November 2008

- ^ Radcliffe and Stand United Reformed Churches, Radcliffe United Reformed Church, retrieved 16 November 2008

- ^ Anon 1905, pp. 23–47.

- ^ Masjid Noor and Islamic Education Centre, UK Mosque Searcher, retrieved 1 December 2008

- ^ Theological and Religious Studies Collection Directory, Assoc. of British Theological and Philosophical Libraries, archived from the original on 8 June 2011, retrieved 1 December 2008

- ^ a b c Nicholls 1900, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Langley 1854, p. 248.

- ^ a b Hudson 2001, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Cricket Nurseries of Colonial Barbados, The Elite Schools, 1865–1966, Press University of the West Indies, 8 August 1998, p. 126, ISBN 978-976-640-046-0, retrieved 29 October 2007

- ^ Radcliffe Town Football Club, radcliffetownfc.co.uk, retrieved 22 June 2009[permanent dead link]

- ^ Borough make their mark on Gascoigne, Bolton Evening News, 24 July 2004, archived from the original on 1 July 2012, retrieved 3 November 2008

- ^ Higginson, Marc (19 July 2012). "London 2012: Craig Dawson's rise to Team GB from glass collector". BBC Sport. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ "Matt Derbyshire: 'I didn't care about the financial side. It was because I supported Rovers as a kid, and was brought up in Blackburn'", The Independent, 14 April 2007, archived from the original on 31 January 2009, retrieved 3 November 2008

- ^ "A fitting tribute to Olympic hero Nellie", Bury Times, 11 September 2007, retrieved 14 August 2012

- ^ Nellie Halstead, Radcliffe AC, archived from the original on 14 February 2015, retrieved 14 August 2012

- ^ New medical centre brings a shopping boost to Radcliffe, burytimes.co.uk, 13 August 2009, retrieved 5 March 2010

- ^ Nicholls 1900, pp. 242–243.

- ^ Borough of Radcliffe 1935, p. 19.

- ^ Lancashire Electric Light and Power, The Times newspaper, 19 February 1922, p. 22

- ^ Frost 1993

- ^ Borough of Radcliffe 1935, p. 20.

- ^ Borough of Radcliffe 1935, p. 25.

- ^ My area: Bury, Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service, archived from the original on 7 April 2008, retrieved 30 October 2008

- ^ "Mystery buyer snaps up police station for £150,000". Bury Times.

- ^ Greater Manchester Waste Disposal Authority (GMWDA), Greater Manchester Waste Disposal Authority, 2008, retrieved 8 February 2008

- ^ Bury, United Utilities, 6 April 2007, archived from the original on 2 January 2010, retrieved 30 October 2008

- ^ 'Back to school' for war hero, archive.lancashireeveningtelegraph.co.uk, 17 November 2000, archived from the original on 7 July 2012, retrieved 1 January 2009

- ^ Cooper, Carol (12 June 2003), Three cheers for a funny fellow, Globeandmail.com, archived from the original on 26 August 2004, retrieved 19 January 2009

- ^ Harry checks progress on his path, Bury Focus, 26 June 2006, retrieved 14 February 2015

- ^ Goodbye to a true cycling superstar, burytimes.co.uk, 5 February 2009, retrieved 14 February 2015

- ^ Hudson 2001, pp. 117–128.

- ^ Rebecca Flint Marx (2009), "Danny Boyle", Movies & TV Dept., The New York Times, Baseline & All Movie Guide, archived from the original on 25 February 2009, retrieved 29 October 2008

- ^ Baxter, Trevor (13 July 2006), "John Spencer", The Independent, archived from the original on 25 October 2012, retrieved 12 December 2008

- ^ Hudson 2001, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Hudson 2001, p. 46.

- ^ Hudson 2001, p. 51.

- ^ Close Park, History, Bury Metropolitan Borough Council, archived from the original on 23 August 2009, retrieved 12 December 2008

- ^ "Band Love Being Back in Town", Bury Times, 27 September 2008, archived from the original on 20 July 2011, retrieved 4 November 2008

- ^ Sunderland 1995, p. 98.

- ^ Nicholls 1900, p. 210.

Bibliography

- Anon (1905), East Lancashire Annual and Historical Record and Business Directory, Radcliffe Library: Unknown

- Augusta, Anna; Ramsay, Whittall (1969), Sir Robert Peel, Ayer Publishing, ISBN 0-8369-5076-3

- Borough of Radcliffe (21 September 1935), Charter Celebrations, Bury Library Local Studies

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Coward, Barry (1983), The Stanleys, Lords Stanley, and Earls of Derby, 1385–1672, Manchester University Press ND, ISBN 0-7190-1338-0

- Darvill, Timothy (2003), The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-280005-3

- Dobb, Rev Arthur Joseph, Vicar of Bircle (1970), 1846 Before and After – A Historical Guide to the Ancient Parish of Bury, Rochdale Library: Bircle Parish Church Council

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Farrer, William; Brownbill, John (1911a), "The Hundred of Salford", A History of the County of Lancaster, Vol. 4, British History Online, retrieved 12 December 2008

- Farrer, William; Brownbill, John (1911b), "The Parish of Prestwich with Oldham – Pilkington", A History of the County of Lancaster, Vol. 5, British History Online, retrieved 4 December 2008

- Farrer, William; Brownbill, John (1911c), "The Parish of Radcliffe", A History of the County of Lancaster, Vol. 5, British History Online, retrieved 11 February 2009

- Frost, Roy (1993), Electricity in Manchester, Roy Frost, ISBN 1-85216-075-6

- Gooderson, P.J. (1985), Thomas & John, Radcliffe Library: RAP ltd, ISBN 0-9510489-0-2

- Hudson, John (2001), Britain in Old Photographs – Radclffe, Budding Books, ISBN 1-84015-219-2

- Landau, Norma (2002), Law, Crime and English Society, 1660–1830, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-64261-2

- Langley, W.H. (1854), Ruff's Guide to the Turf, Piper, Stephenson and Spence

- McNeil, R; Nevell, M (2000), A Guide to the Industrial Archaeology of Greater Manchester, Association for Industrial Archaeology, ISBN 0-9528930-3-7

- Mills, A.D. (1998), "Radcliffe", A Dictionary of British Place-Names (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-280074-4, retrieved 21 November 2008

- Nicholls, W. (1900), History and Traditions of Radcliffe, John Heywood ltd

- Russell, Bertrand (2001), Freedom and Organisation, 1814–1819, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-24999-6

- Simpson, Robert (1852), The History and Antiquities of the Town of Lancaster, Oxford University: T. Edmondson; J.R. Smith

- Simpson, Barry J. (1994), Urban Public Transport Today, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-419-18780-4

- Smith, Leah (1981), Bits of Local History by "Owd Linthrin Bant", Radcliffe Library: Radcliffe Local History Society 1981

- Sunderland, Frank (1995), The Book of Radcliffe, Bury Library Local Studies: Baron Birch, ISBN 0-86023-561-0

- Wells, Jeffrey (1995), An Illustrated Historical Survey of the Railways in and Around Bury, Challenger Publications, ISBN 1-899624-29-5

- Youngs, F.A. (1991), Guide to the local administrative units of England. Volume II: Northern England, London: Royal Historical Society, ISBN 0-86193-127-0

External links

[edit]