Olivenza

Olivenza

Olivença | |

|---|---|

Municipality | |

| |

| |

Location in the Spanish–Portuguese border | |

| Coordinates: 38°41′9″N 7°6′3″W / 38.68583°N 7.10083°W | |

| Country | Spain[a] |

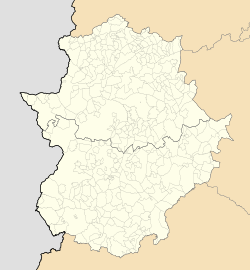

| Autonomous community | Extremadura |

| Province | Badajoz |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Manuel José González Andrade (PSOE) |

| Area | |

• Total | 430.1 km2 (166.1 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 327 m (1,073 ft) |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

• Total | 11,986 |

| • Density | 28/km2 (72/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 06100 |

| Website | Town Hall (in Spanish) |

Olivenza (Spanish: [oliˈβenθa] ⓘ) or Olivença (Portuguese: [oliˈvẽsɐ]) is a town in southwestern Spain, close to the Portugal–Spain border. It is a municipality belonging to the province of Badajoz, and to the wider autonomous community of Extremadura.

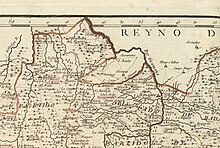

The town of Olivença was under Portuguese sovereignty continuously between 1297 (Treaty of Alcañices) and 1801, when it was occupied by Spain during the War of the Oranges and ceded that year under the Treaty of Badajoz. Spain has since administered the territory (now split into two municipalities, Olivenza and Táliga), whereas Portugal invokes the self-revocation of the Treaty of Badajoz, plus the Congress of Vienna of 1815, to claim the return of the territory. In spite of the territorial dispute between Portugal and Spain, the issue has not been a sensitive matter in the relations between these two countries.[2][3]

Olivenza and other neighbouring Spanish (La Codosera, Alburquerque and Badajoz) and Portuguese (Arronches, Campo Maior, Estremoz, Portalegre and Elvas) towns reached an agreement in 2008 to create a euroregion.[4][5]

Geography

[edit]Olivenza is located on the left (east) bank of the Guadiana river,[6] at an equal distance of 24 kilometres (15 miles) south of Elvas in Portugal and Badajoz in Spain. The territory is triangular, with a smaller side resting on the Guadiana and the opposite vertex entering south-east and surrounded by Spanish territory. Besides the city, the municipality of Olivenza also includes other minor villages: San Francisco (Portuguese: São Francisco), San Rafael (São Rafael), Villarreal (Vila Real), Santo Domingo de Guzman (São Domingos de Gusmão), San Benito de la Contienda (São Bento da Contenda), and San Jorge de Alor (São Jorge da Lor).

The catchment area which drains Olivenza consists of irregular water streams regularly drying up in the Summer.[7] The Olivenza river—whose water is dammed up in the reservoir of Piedra Aguda, opened in 1956 and with a capacity of 16.3 hm3—discharges into the Guadiana,[7] leaving the city to its west and, then, south. Closer to the city (which is sandwiched in between the course of the lesser creeks of the Arroyo de la Charca and the Arroyo de la Higuera),[8] there is an artificial pond, the charca of Ramapallas.[7]

History

[edit]It is possible the settlement did not exist during the Muslim period.[9] A 1278 document refers to the place as 'populated again', but this is not conclusive.[10] Badajoz and its surrounding territory (including the lands around Olivenza) were conquered by Alfonso IX of León in 1230.[11] Taken away from the alfoz of Badajoz, the Knights Templars had occupied the territory already by 1258,[12] founding an encomienda in Olivenza integrated in the Bailiwick of Jerez de los Caballeros.[13] They proceeded to build a castle and a church as core of the hamlet, following the templar model of repopulation.[14]

The second half of the 13th century saw continual territorial disputes between the Order of the Temple and the council of Badajoz over the lands north of the Fragamuñoz creek, and the municipal militias of Badajoz invaded Cheles, Alconchel and Barcarrota in 1272, although those territories were retroceded to the Order by means of a 1277 settlement.[15] Soon later, by 1278,[16] Alfonso X recognised the jurisdiction of the Council of Badajoz and the Diocese over Olivenza, putting an end to the Templar control over the hamlet. Amid a situation of unrest in the Crown of Castile in the wake of the death of King Sancho IV, King Dinis of Portugal forced King Ferdinand IV to sign the Treaty of Alcañices in 1297 and cede, amongst other possessions, Olivenza to the Kingdom of Portugal.[17] On 4 January 1298, Dinis granted Olivenza a foral (charter) similar to that of Elvas.[18]

- 1510 – King Manuel I of Portugal renews the town charter and orders the building of fortifications and the Olivenza Bridge over the Guadiana River (Ponte de Olivenza, later known as Ponte de Nossa Senhora da Ajuda (Our Lady of Help Bridge) or, simply as Ajuda bridge), on the road to Elvas. Construction of Santa Maria Madalena Church begins. This church would be the residence of the Bishop of Ceuta for many years.

Following the start of the war between Castile and Portugal in 1640 (variously known as Secession, Aclamation, Restoration or Portuguese Independence War),[20] Olivenza was taken in 1657 by forces loyal to the Spanish Monarchy led by Neapolitan governor Francesco Tuttavilla, Duke of San Germán after a long siege.[21] By means of the 1668 Treaty of Lisbon, Olivenza was returned to the Kingdom of Portugal.[22]

In the context of the War of the Spanish Succession, the Ajuda Bridge was used for the retreat of the Anglo-Portuguese army after they were crushed at the Battle of La Gudiña in May 1709.[23] The victorious Spanish Bourbon army led by the Marquis de Bay ordered its destruction to prevent the Portuguese using it again.[24]

In the wake of the Portuguese refusal to enter an alliance with France and Spain against Britain, the brief War of the Oranges began in 1801, with the French troops marching on Portugal, then followed by Spanish troops. Olivenza capitulated to the Spanish army led by Godoy on 20 May 1801.[25][26] The 1801 Treaty of Badajoz putting an end to the war returned to Portugal the occupied towns except those on the left bank of the Guadiana river (the territory of Olivenza),[25] which were ceded to Spain, including its inhabitants, on a 'perpetual' basis. The Treaty also stipulated that the breach of any of its articles would lead to its cancellation.[27]

- 1801

- 29 January 1801 – Treaty of Badajoz is signed between France, Spain and Portugal. If Portugal does not comply with the terms, it would give Spain and France a reason for invasion

- 20 May 1801 – Spanish troops enter Portugal alongside the French, effectively invading Portuguese border towns after Portugal does not comply with the terms of the Treaty of Badajoz.

- 6 June 1801 – Portugal, Spain and France sign the Treaty of Badajoz, in which Olivenza is given to Spain.

- 1805

- 26 January 1805 – The Portuguese currency is forbidden.

- 20 February 1805 – Teaching in Portuguese is forbidden.

- 14 August 1805 – Adoption of the Spanish language in city hall documents.

- 1807

- October – Treaty of Fontainebleau (1807) between Spain and France dividing Portugal and all Portuguese dominions between them.

- November – French and Spanish troops again march over Portugal, in the Peninsular War.

- 1808

- 1809

- July – Portugal presents to the Supreme Central Junta, in Seville, an official order of restitution of the territory of Olivenza.

- 1810

- 19 February 1810 – Treaty of alliance and friendship between Portugal and Britain, whereby the United Kingdom pledges to help Portugal to regain possession of Olivenza, in turn receiving the exploration of the Portuguese establishments of Bissau and Cacheu for a period of 50 years.

- Portugal starts negotiating a treaty with the Regency Council of Spain, whereby Olivenza should be given back to Portugal.

- 1811

- 15 April 1811 – Beresford, a British marshal serving as Commander-in-chief of the Portuguese Army, briefly retakes Olivenza.[25]

- 1813

- 19 May 1813 – The remaining Portuguese language private schools are closed by the Spanish authorities.[citation needed]

- 1814

- 30 May 1814 – The Treaty of Paris between France and Portugal includes a provision declaring the 1801 treaties of Badajoz and Madrid null and void. Spain is not a part of this agreement.

- 1815

- 9 June 1815 – The Portuguese delegation to the Congress of Vienna, led by Pedro de Sousa Holstein, succeeds in including article 105 in the Final Act (aka the Treaty of Vienna), stating that the winning countries are to endeavour with the mightiest conciliatory effort to return Olivenza to Portuguese authority. The Spanish representative to the Congress, Pedro Gomes Labrador, refuses to sign the Treaty, registering a protest against several of the Congress resolutions, including article 105.

- 27 October 1815 – Expecting the quick restitution of Olivenza, Prince Regent John nominates José Luiz de Sousa as Plenipotentiary.

- 29 January 1817 – Portugal occupies Uruguay due to rebel threats against Brasil.

- 7 May 1817 – Spain finally ratifies the Treaty of Vienna.

- 1818–1819 – Spain and Portugal, with the mediation of France, the United Kingdom, Russia and Austria, negotiate in the Conference of Paris toward a peaceful restitution of Uruguay to Spain. Spain accepts the terms of an agreement proposed by the mediators but due to internal problems and the Liberal Revolution in 1820, actions never took place.

- 7 November 1820 – Spanish authorities forbade the use of private teaching in Portuguese.

- 1821 – Portugal annexes Uruguay. In reaction, Spain withdraws from the Olivenza talks.

- 1840 – The Portuguese language is forbidden in the territory of Olivenza, including inside churches.

- 1850 – The village of Táliga is separated to form its own municipality.

- 1858 – Isabel II of Spain grants the title of City (Ciudad) to Olivenza.

- 29 September 1864 – The Treaty of Lisbon (1864) between Portugal and Spain is signed, demarcating the border from the estuary of the Minho river, on the far North, to the confluence of the Caya River with the Guadiana river, just north of Olivenza. The demarcation of the border is not pursued further because of the situation of Olivenza.

- 1918/1919 – With the end of World War I, the Portuguese government studies the possibility of taking the situation of Olivenza to the Paris Peace Conference. However, as Spain had not participated in the War, the intervention of the international community in this issue is not possible.

- 29 June 1926 – Portugal and Spain sign the Convention of Limits (1926) an agreement demarcating the border from the confluence of Ribeira de Cuncos with the Guadiana, just south of Olivenza, to the estuary of the Guadiana, on the far South. The border between Portugal and Spain from the confluence of the Caya river to the confluence of the Cuncos is not demarcated and remains so nowadays, with the Guadiana being the de facto border.

- 1936–1939 – During the Spanish Civil War, Portuguese Colonel Rodrigo Pereira Botelho volunteers to occupy Olivenza. The 8th Portuguese Regiment, stationed in nearby Elvas, prepares to take Olivenza but is ordered not to.[citation needed]

- 15 August 1938 – The Pro-Olivenza Society (Sociedade Pró-Olivença) is founded, the first of a number of pressure groups established to advance the cause of Olivenza in Portugal.

- 1954 – Oliventine children are no longer allowed to take free holidays in the Portuguese seaside resort "Colónia Balnear Infantil d'O Século" (in São Pedro do Estoril), managed by a newspaper owned charity.

- 24 January 1967 – The Portuguese government declares the Ponte da Ajuda Bridge a National Heritage Monument.

- 1968 – A covenant between Portugal and Spain on exploitation of hydraulic resources in the frontier rivers is signed. All frontier rivers (including the non-demarcated section in the Guadiana river) are covered, distributing the hydraulic exploitation between both countries. The hydraulic exploitation of the non-demarcated section in the Guadiana river is assigned to Portugal (in the same way as the rights on hydraulic exploitation over other frontier rivers are assigned either to Portugal or to Spain). The only difference between this section and the rest is that the term "international" is omitted (all the sections are named "international section" but the non-demarcated one in the Guadiana river).[28]

- 1977 – A Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation between Spain and Portugal is signed, in which both countries ratified the integrity and inviolability of their respective territories[29] thereby effectively assuming Olivenza is under Spanish control.

The municipality lost an important chunk of its population from 1960 to 1975, with many working-age migrants moving to other Spanish cities (Madrid, Barcelona, Bilbao, Lleida) in the wake of the implementation of the Stabilization Plans but also moving abroad to countries such as Switzerland, Germany and France.[30]

- 1981 – Former prime minister of Portugal, admiral Pinheiro de Azevedo publishes a book on Olivenza and visits the town, leading Spain to send a contingent of the Civil Guard (Guardia Civil) to prevent any confrontation.[citation needed]

- 1990

- In an Iberian Summit, the prime ministers of Portugal and Spain sign a covenant for the joint effort to preserve the Ponte da Ajuda Bridge, as well as the construction of a new bridge alongside it, also as a joint effort.

- Elvas and Olivenza became friendship towns.

- 1994, November – After internal criticism that the agreement of 1990 would mean the recognition of the de facto border by the government of Portugal, the agreement is modified in another Iberian Summit. Portugal is now in full charge of constructing the new bridge and preserving the old bridge, therefore not putting the Portuguese claim to the territory of Olivenza at stake.[citation needed]

- March 1995 – The Portuguese government sends its Spanish counterpart a study on the effects that the construction of the Alqueva Dam would have on Spanish territory. Information on Olivenza is not included. Later, Portugal sends further information, including data on Olivenza, under the title "Territory of Spain and Olivenza".

- October 1999 – The Spanish police stop preservation works being undertaken by the Portuguese on the old Ponte da Ajuda Bridge on the left bank (Spanish side) of the Guadiana river. The Portuguese had been working on that side of the bridge without Spanish permits assuming that the left bank-side of the Guadiana river belonged to Portugal, according to the 1968 covenant.[citation needed] In subsequent events, a Portuguese court order prevents Spain from taking over the works.[citation needed]

- 11 November 2000 – The new Olivenza Bridge, constructed by Portugal and Spain, is inaugurated.

- 2003

- Spain restarts work on the old bridge, under protest from the Portuguese government.[citation needed]

- 2004

- 25 June 2004 – The Portuguese parliament raises the issue of Olivenza and exhorts the Minister of Foreign Affairs to try to solve the question, in a friendly and cooperative way, with Spain and the people of Olivenza, within the European Union.[citation needed]

- 4 September 2004 – The Portuguese Minister of Foreign Affairs, Antonio Martins da Cruz states that the Olivenza issue "is frozen".[3][31]

- 7 September 2004 – The government of the autonomous community of Extremadura declares the old Ponte da Ajuda Bridge a Heritage Monument.[32]

- 2007 – Guillermo Fernández Vara, who was born in Olivenza, is elected president of Extremadura.

- 2010 – The ancient Portuguese street names, that were removed in the first half of the 20th century, return to the historical city centre of Olivenza.[33]

- December 2014 – Portuguese nationality is given to 80 residents of Olivenza, after their formal request. 90 other similar requests from residents of Olivenza are received by the Portuguese authorities. That represents less than 0.75 per cent of Olivenza's population which, as of the 2021 census, is 11,871 inhabitants.[34] In the beginning of 2018, the number of residents with Portuguese nationality is around 800 (6% of the town's population).[35]

- 1 December 2018 – The Olivenza Marching Band participates in the Portuguese bands parade in Lisbon, in commemoration of the 1640 Restoration of the Portuguese Independence.

- 2019 – For the first time, citizens of Olivenza with Portuguese citizenship could vote for the 2019 Portuguese legislative election (though by postal voting).[36]

- 2024 – During a ceremony marking Cavalry Regiment No. 3 (RC3) Day in Estremoz, Portugal's Defense Minister Nuno Melo stated that Olivença "is Portuguese" and that the country "will not give up" on it.[37] Later, he clarified on his X page that this was a personal opinion he had expressed while leader of the CDS – People's Party, not in his capacity as defense minister.[38]

Demographics

[edit]The total population is 11,871 (2021). The total area is 750 square kilometres (290 sq mi). Like the surrounding regions, population density is low, at 11 inhabitants per km2.

There are still traces of Portuguese culture and language in the people, although the younger generations speak Spanish.

At the beginning of the 1940s the city was reportedly mainly Portuguese-speaking (mother language spoken at home), even after close to 150 years under Spanish control. It was after the 1940s, under Franco dictatorship, that a gradual language shift towards Spanish as native language took place as it looked to unite Spain and erase all signs of other cultures: the typically Portuguese looking streets had their names changed to Spanish, the Portuguese language was banned (making most people only able to speak Portuguese secretly inside their home), the education of children was controlled and even the names of Portuguese people changed to Spanish equivalent names (although some families kept using their Portuguese names and attributing Portuguese nicknames per family as an act of rebellion against the government).

After the 1970s, there was an ease on the early dictatorship policy.

Since 2021, around 1,300 inhabitants (8% of the town's population) have asked for dual citizenship, and about 92% have not acquired Portuguese citizenship. As of 2018, 1,500 inhabitants (about 12% of the population) are bilingual Portuguese-Spanish (mostly among those born before 1950).

The European Commission showed some concern over the years regarding the need to protect the Portuguese language in the area. After some time, the children of Olivenza started learning Portuguese in school again.

An unofficial census carried out among the citizens of Olivenza overwhelmingly stated that the citizens of the town feel more Spanish than Portuguese, and most of them want to remain in Spain, even though it is unclear whether this is due to a sense of Spanish identity or simply due to Portugal's current economic status. However, it must also be noted that even in the twenty-first century, after the Franco dictatorship, many who tried to stand for their heritage and culture were declared personae non gratae and some were accused of "disrespecting the Spanish flag" for protecting the Portuguese language.[39]

Landmarks

[edit]In 1964, Olivenza became one of the first municipalities in the province of Badajoz that earned a heritage protection status of conjunto histórico-artístico for their historic cores.[40] The report for the declaration cited that the city of Olivenza, "surrounded by a beautiful landscape of pasture and farmland, dominated by the imposing castle's keep", "offers a number of buildings, enclosures and places of notable importance in the monumental aspect".[41]

Some landmarks include the church of Saint Mary of the Castle (Spanish: Iglesia de Santa María del Castillo, Portuguese: Igreja de Santa Maria do Castelo), Holy Ghost Chapel (Capilla del Espíritu Santo, Capela do Espírito Santo), Saint Mary Magdalene Church (Iglesia de Santa María Magdalena, Igreja de Santa Maria Madalena, considered a masterwork of Portuguese Manueline architecture), Saint John of God Monastery (Monasterio de San Juan de Dios, Mosteiro de São João de Deus), the keep (torre del homenaje, torre de menagem), and the ruins of the Our Lady of Help Bridge (Puente de Nuestra Señora de Ayuda, Ponte de Nossa Senhora da Ajuda, destroyed in 1709 and never rebuilt).

-

Church interior, built in Manueline late-gothic style.

-

Door of the Olivenza's city hall, also Manueline

Claims of sovereignty

[edit]Portugal does not recognise Spanish sovereignty over the territory, based on the rulings of the 1815 Congress of Vienna. Spain accepted the Treaty on 7 May 1817; however, Olivença and its surroundings were never returned to Portuguese control and this question remains unresolved[42] and Portugal holds a claim over it.[42] Olivenza was under Portuguese sovereignty from 1297.[citation needed] During the War of the Oranges, French and Spanish troops, under the command of Manuel de Godoy, took the town on 20 May 1801. In the aftermath of that conflict, the Treaty of Badajoz was signed, with the Olivenza territory remaining a part of Spain. According to Portugal, however, the treaty is void since Portugal was coerced into signing it, meaning it does not show the deliberate intent and "free will" necessary for treaty validity under international law and the subsequent position of Portugal after 200 years of not recognising it as a legitimate part of Spain seems to confirm exactly that.

Spain claims ‘de jure’ sovereignty over Olivenza on the grounds that the Treaty of Badajoz still stands and has never been revoked, thus making the case that the border between the two countries in the region of Olivenza should be demarcated as said by the treaty.

Portugal claims de jure sovereignty over Olivenza on the grounds of the cancellation of the Treaty of Badajoz, since it was revoked by its own terms. The breach of any of its articles would lead to its cancellation, and that happened when Spain invaded Portugal in the Peninsular War of 1807. Portugal further bases its case on Article 105 of the Treaty of Vienna of 1815 (which Spain signed in 1817) that states that the winning countries are "committed to employ the mightiest conciliatory effort to return Olivenza to Portuguese authority" and that the winning countries "recognize that the return of Olivenza and its territories must be done".[43] Thus, the border between the two countries in the region of Olivenza should be demarcated by the Treaty of Alcanizes of 1297 and that the duty acknowledged by Spain to give back the region must be carried out.

Spain interprets Article 105 as not being mandatory on demanding Spain to return Olivenza to Portugal, thus not revoking the Treaty of Badajoz.

Even though Portugal has never made a formal claim to the territory after the Treaty of Vienna, it has not directly acknowledged Spanish sovereignty over Olivença either but has funded several projects connected to the region instead of the Spanish Government.

Portuguese military maps do not show the border at that area, implying it to be undefined.[44][45] Also, the latest road connection between Olivenza and Portugal (entirely paid by the Portuguese state,[46] although it involved the building of a bridge over the Guadiana, an international river) has no indication of the Portuguese border, again implying an undefined status.

There is no research on the opinion of the inhabitants of Olivenza about their status. Spanish public opinion is not generally aware of the Portuguese claim on Olivenza. On the other hand, awareness in Portugal has been increasing under the efforts of pressure groups to have the question raised and debated in public.[47][48][49]

Famous people born in Olivenza

[edit]- Guillermo Fernández Vara (1958) – Spanish politician, president of Extremadura.

- Pedro da Fonseca (?–1422) – Portuguese cardinal.

- Paulo da Gama (1465-1499), Vasco da Gama's elder brother, commander of São Rafael in the discovery of the route to India.

- Vicente Lusitano (c. 1461 – c. 1561) – Portuguese composer and music theoretician.

- Tomás Romero de Castilla (1833–1910) – Spanish theologian, founder of the Museo Arqueológico Provincial de Badajoz.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Citations

- ^ Municipal Register of Spain 2018. National Statistics Institute.

- ^ Merida, J. C. Z. (5 September 2003). "Portugal desmiente a la CIA y niega que haya un conflicto por Olivenza". El Periódico Extremadura (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 26 July 2011.

- ^ a b "Martins da Cruz Afirma Que a Questão de Olivença "Está Congelada"". Grupo dos Amigos de Olivença (in Portuguese). 5 September 2003. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- ^ Leon, F. (18 March 2008). "Europacto en la frontera hispano-lusa". El Periódico Extremadura (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 26 July 2011.

- ^ "Euroregião e Declaração de Olivença". www.cm-estremoz.pt (in Portuguese). [permanent dead link]

- ^ Pizarro Gómez 2010, p. 75.

- ^ a b c Zamora Rodríguez & Beltrán de Heredia Alonso 2006, p. 1192.

- ^ Zamora Rodríguez & Beltrán de Heredia Alonso 2006, p. 1219.

- ^ Clemente Ramos 1994, p. 691.

- ^ Clemente Ramos, Julián (1994). "La Extremadura musulmana (1142-1248). Organización defensiva y sociedad". Anuario de Estudios Medievales. 24 (1). Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas: 691. doi:10.3989/aem.1994.v24.995. S2CID 159559658.

- ^ Russo, Mariagrazia (2007). "O espaço linguístico fronteiriço luso-espanhol. Percursos para a construção de identidades. Um olhar na raia alentejana / raya extremeña". Atas do Simpósio Mundial de Estudos de Língua Portuguesa. University of Salento. doi:10.1285/i9788883051272p2077. ISBN 978-88-8305-127-2.

- ^ Peralta y Carrasco, Manuel (2000). "El llamado Fuero de Baylío : Historia y vigencia del fuero extremeño". Brocar (24): 7–18. doi:10.18172/brocar.1699.

- ^ "plan general municipal de olivenza - SITEX".

- ^ Pizarro Gómez 2010, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Segovia, R.; Caso, R., eds. (2018). "La Orden del Temple y la frontera luso-leonesa (1145-1310)". Las frontera con Portugal a lo largo de la Historia: a propósito del 350 aniversario de la firma del Tratado de Lisboa (1668-2018). III Jornadas de Historia en Jerez de los Caballeros (6 de octubre de 2018). Jerez de los Caballeros: Xerez Equitum. p. 42.

- ^ Pizarro Gómez 2010, p. 76.

- ^ Ventura, Margarida Garcez (2007). A definição das fronteiras, 1096–1297 (in Portuguese). Matosinhos: Quidnovi Editora. ISBN 978-972-8998-85-1.

- ^ Peralta y Carrasco 2000, p. 8.

- ^ Pizarro Gómez 2010, pp. 83, 87.

- ^ García Blanco, Julián (2020). "La fortificación abaluartada de Olivenza en el siglo XVII. Origen y desarrollo" (PDF). I Jornada de fortificaciones abaluartadas y el papel de Olivenza en el sistema luso-español.

- ^ Revilla Canora, Javier (2015). "Un noble napolitano en la Guerra de Portugal: Francesco Tuttavilla, duque de San Germán, general del ejército de Extremadura" (PDF). II Encuentro de Jóvenes Investigadores en Historia Moderna. Líneas recientes de investigación en Historia Moderna. Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. pp. 392–393. ISBN 978-84-15305-87-3.

- ^ Pizarro Gómez 2010, p. 90.

- ^ Cayetano Rosado 2013, pp. 1726–1728.

- ^ Cayetano Rosado, Moisés (2013). "Del asedio de Badajoz en 1705 al de Campo Maior en 1712" (PDF). Revista de Estudios Extremeños. 69 (3): 1728.

- ^ a b c d Vicente, António Pedro (2007). Guerra peninsular, 1801–1814 (in Portuguese). Matosinhos: Quidnovi Editora. ISBN 978-972-8998-86-8.

- ^ Lavado Rodríguez, Fabián (2021). "La plaza de Olivenza en 1801/02" (PDF). O Pelourinho: Boletin de Relaciones Transfronterizas (25): 144. ISSN 1136-1670.

- ^ a b In Ventura, António (2008). Guerra das Laranjas, 1801 (in Portuguese). Matosinhos: Quidnovi Editora. ISBN 978-989-628-075-8., the text of the Treaty of Badajoz: "[Preamble] [...] dois Tratados, sem que na parte essencial seja mais do que um, pois que a Garantia é recíproca, e não haverá validade em alguns dos dois, quando venha a verificar-se a infracção em qualquer dos Artigos, que neles se expressam. [...] Artigo I: Haverá Paz [...] entre Sua Alteza Real o Príncipe Regente de Portugal, e dos Algarves, e Sua Majestade Católica El-Rei de Espanha, assim por mar, como por terra em toda a extensão dos seus reinos [...]. Artigo III: Sua Majestade Católica [...] conservará em qualidade de Conquista para unir perpetuamente aos seus Domínios, e Vassalos, a Praça de Olivença, seu Território, e Povos desde o Guadiana; de sorte que este Rio seja o limite dos respectivos Reinos, naquela parte que unicamente toca ao sobredito Território de Olivença. [...] Artigo IX: Sua Majestade Católica se obriga a Garantir a Sua Alteza Real o Príncipe Regente de Portugal a inteira conservação dos Seus Estados, e Domínios sem a menor excepção, ou reserva. [...]"

- ^ Instrumento de ratificación del Convenio y Protocolo adicional entre España y Portugal para regular el uso y aprovechamiento hidráulico de los tramos internacionales de los ríos Limia, Miño, Tajo, Guadiana y Chanza y sus afluentes, firmado en Madrid el 29 de mayo de 1968.. Article III states:

El aprovechamiento hidráulico de las siguientes zonas de los tramos internacionales de los restantes ríos mencionados en el artículo primero será distribuido entre España y Portugal de la forma siguiente:

[...]

E) Se reserva a Portugal la utilización de todo el tramo del río Guadiana entre los puntos de confluencia de éste con los ríos Caya y Cuncos, incluyendo los correspondientes desniveles de los afluentes en el tramo.In the same article, sections A and B are assigned to Portugal, while C, D and F are assigned to Spain.

- ^ "Instrumento de ratificación de España del tratado de amistad y cooperación entre España y Portugal, hecho en Madrid el día 22 de noviembre de 1977" (in Spanish) – via www.boe.es.

- ^ Vallecillo Teodoro 2017, p. 1513.

- ^ ""Una cuestión congelada", según Portugal". ABC (in Spanish). 15 September 2003.

- ^ "Resolución de 6 de septiembre de 2004, de la Consejería de Cultura, por la que se incoa expediente de declaración de bien de interés cultural, para el puente de Ajuda en la localidad de Olivenza (Badajoz)" (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 March 2021 – via www.boe.es.

- ^ Maneta, Luis (11 June 2010). "Ruas de Olivença voltam a ter nomes portugueses". Diário de Notícias (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ "Dezenas de habitantes de Olivença pedem e obtêm nacionalidade portuguesa". Diário Digital (in Portuguese). Lusa. 26 December 2014. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016.

- ^ Dores, Roberto (5 March 2018). "Afeto cultural e oportunidade de emprego levam oliventinos à dupla nacionalidade". Diário do Sul (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 4 December 2018.

- ^ "Olivença cada vez mais portuguesa" (in Portuguese). Sol. 14 March 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ Agência Lusa (13 September 2024). "Nuno Melo diz que Olivença 'é portuguesa' e país 'não abdica'" [Nuno Melo says that Olivença 'is Portuguese' and that the country 'will not give up']. Observador (in Portuguese). Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ @NunoMeloCDS (13 September 2024). "A opinião que tenho sobre Olivença é antiga e corresponde a uma posição de princípio, historicamente conhecida, que várias vezes defendi. Hoje repeti-a como presidente do CDS, embora num contexto equívoco, porque presente numa cerimónia como ministro" [The opinion I have about Olivença is old and corresponds to a historically known principled position that I have defended several times. Today I repeated it as president of the CDS, although in an equivocal context, because I was present at the ceremony as minister] (Tweet) (in Portuguese). Retrieved 7 January 2025 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Olivença cada vez mais portuguesa" (in Portuguese). Sol Sapo. 14 March 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ Pardo Fernández 2013, p. 815.

- ^ Pardo Fernández 2013, pp. 815–816.

- ^ a b Guo, Rongxing (2007). Territorial Disputes and Resource Management: A Global Handbook. New York: Nova Science Publisher. p. 199. ISBN 9781600214455.

- ^ "Spain". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 13 December 2021.

- ^ "CIGeoE - Centro de Informação Geoespacial do Exército". www.igeoe.pt.

- ^ "CIGeoE - Centro de Informação Geoespacial do Exército". www.igeoe.pt.

- ^ "Portugal Fronteira invisível. "Se um dia Portugal e Espanha se unirem, a capital será Olivença"". Jornal i (in Portuguese). 28 September 2012. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014.

- ^ Jefferies, Anthony (19 August 2006). "The Best of Both Worlds". Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ Mora, Miguel (4 December 2000). "La eterna disputa de Olivenza-Olivença". El País (in Spanish). Ediciones El País, S.L. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ Caetano, Filipe (18 January 2008). "Cimeira Ibérica: Olivença ainda é questão?". IOL Diário (in Portuguese). Media Capital Multimedia. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- Bibliography

- Pardo Fernández, María Antonia (2013). "El arquitecto José Menéndez-Pidal y sus criterios de restauración monumental sobre los conjuntos históricos artísticos" (PDF). Laboratorio de Arte. 25 (2). Seville: Universidad de Sevilla. ISSN 1130-5762.

- Pizarro Gómez, Francisco Javier (2010). "Olivenza: Modelo de transferencias arquitectónicas y urbanísticas entre España y Portugal" (PDF). Quintana (9). Santiago de Compostela: Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. Servicio de Publicaciones: 75–101. ISSN 1579-7414.

- Zamora Rodríguez, Beatriz; Beltrán de Heredia Alonso, Jesús. "Calidad y aprovechamiento de las aguas del Guadiana transfronterizo extremeño-alentejano" (PDF). Revista de Estudios Extremeños. 62 (3). Badajoz: Diputación Provincial de Badajoz: 1189–1244. ISSN 0210-2854.

- Vallecillo Teodoro, Miguel Ángel (2017). "Aproximación a 90 años de historia. Olivenza (1927-2017)" (PDF). Revista de Estudios Extremeños. 73 (2): 1505–1524. ISSN 0210-2854.

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Claimed by Portugal

External links

[edit]- CIA World Factbook reference to Olivenza in the "Disputes – international" section on the Spain page

- (in Portuguese) Official Map of Portugal with Olivenza IGEOE

- Official Portuguese statements GAO Archived 2014-04-05 at the Wayback Machine

- CIA World Factbook reference to Olivença in the "Disputes – international" section on the Portugal page

- (in Spanish) Olivenza in the official website of the Province of Badajoz

- (in Spanish) Olivenza in the official website for Tourism in the Region of Extremadura

- Website for Portuguese pressure group "Group of Friends of Olivenza" Archived 2014-04-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Portuguese, Spanish Website for Oliventino cultural group Alemguadiana