Pierre Trudeau: Difference between revisions

m r2.7.2) (Robot: Adding eu:Pierre Trudeau |

|||

| Line 77: | Line 77: | ||

Pierre Trudeau was born in [[Montreal]] to [[Charles Trudeau (businessman)|Charles-Émile Trudeau]], a [[French Canadian]] businessman and lawyer, and Grace Elliott, who was of French and [[Scottish-Canadian|Scottish]] descent. He had an older sister named Suzette and a younger brother named Charles Jr.; he remained close to both siblings for his entire life. The family had become quite wealthy by the time Trudeau was in his teens, as his father sold his prosperous gas station business to Imperial Oil.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.theglobeandmail.com/series/trudeau/ambulant.html |work=Globe and Mail |work=Pierre Elliott Trudeau: 1919–2000 |title=Ambulant life made him one-of-a-kind |first=Donn |last=Downey |date=September 30, 2000 |accessdate=2006-12-05 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20070329214314/http://www.theglobeandmail.com/series/trudeau/ambulant.html <!-- Bot retrieved archive --> |archivedate =2007-03-29}}</ref> Trudeau attended the prestigious [[Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf]] (a private French [[Jesuit]] school), where he supported [[Quebec nationalism]]. Trudeau's father died when Pierre was in his mid-teens. This death hit him and the family very hard. Pierre remained very close to his mother for the rest of her life.<ref name="Memoirs 1993"/> |

Pierre Trudeau was born in [[Montreal]] to [[Charles Trudeau (businessman)|Charles-Émile Trudeau]], a [[French Canadian]] businessman and lawyer, and Grace Elliott, who was of French and [[Scottish-Canadian|Scottish]] descent. He had an older sister named Suzette and a younger brother named Charles Jr.; he remained close to both siblings for his entire life. The family had become quite wealthy by the time Trudeau was in his teens, as his father sold his prosperous gas station business to Imperial Oil.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.theglobeandmail.com/series/trudeau/ambulant.html |work=Globe and Mail |work=Pierre Elliott Trudeau: 1919–2000 |title=Ambulant life made him one-of-a-kind |first=Donn |last=Downey |date=September 30, 2000 |accessdate=2006-12-05 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20070329214314/http://www.theglobeandmail.com/series/trudeau/ambulant.html <!-- Bot retrieved archive --> |archivedate =2007-03-29}}</ref> Trudeau attended the prestigious [[Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf]] (a private French [[Jesuit]] school), where he supported [[Quebec nationalism]]. Trudeau's father died when Pierre was in his mid-teens. This death hit him and the family very hard. Pierre remained very close to his mother for the rest of her life.<ref name="Memoirs 1993"/> |

||

According to long-time friend and colleague [[Marc Lalonde]], the clerically influenced dictatorships of [[António de Oliveira Salazar]] in Portugal (the [[Estado Novo (Portugal)|Estado Novo]]), [[Francisco Franco]] in Spain (the [[Spanish State]]), and Marshal [[Philippe Pétain]] in [[Vichy France]] were seen as political role models by many youngsters educated at elite Jesuit schools in Quebec. Lalonde asserts that Trudeau's later intellectual development as an "intellectual rebel, anti-establishment fighter on behalf of unions and promoter of religious freedom" came from his experiences after leaving Quebec to study in the United States, France and England, and to travel to dozens of countries. His international experiences allowed him to break from Jesuit influence and study French philosophers such as [[Jacques Maritain]] and [[Emmanuel Mounier]] as well as [[John Locke]] and [[David Hume]].<ref>{{cite news |work=Globe and Mail |title=Closest friends surprised by Trudeau revelations |date=April 8, 2006 |url=http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/story/LAC.20060408.TRUDEAU08/TPStory/?query=Pierre+Trudeau+Hugh+Winsor |format=fee required |first=Hugh |last=Winsor |page=A6 |accessdate=2006-12-05}}</ref> |

According to long-time friend and colleague [[Marc Lalonde]], the clerically influenced dictatorships of [[António de Oliveira Salazar]] in Portugal (the [[Estado Novo (Portugal)|Estado Novo]]), [[Francisco Franco]] in Spain (the [[Spanish State]]), and Marshal [[Philippe Pétain]] in [[Vichy France]] were seen as political role models by many youngsters educated at elite Jesuit schools in Quebec. Lalonde asserts that Trudeau's later intellectual development as an "intellectual rebel, anti-establishment fighter on behalf of unions and promoter of religious freedom" came from his experiences after leaving Quebec to study in the United States, France and England, and to travel to dozens of countries. His international experiences allowed him to break from Jesuit influence and study French philosophers such as [[Jacques Maritain]] and [[Emmanuel Mounier]] as well as [[John Locke]] and [[David Hume]].<ref>{{cite news |work=Globe and Mail |title=Closest friends surprised by Trudeau revelations |date=April 8, 2006 |url=http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/story/LAC.20060408.TRUDEAU08/TPStory/?query=Pierre+Trudeau+Hugh+Winsor |format=fee required |first=Hugh |last=Winsor |page=A6 |accessdate=2006-12-05}}</ref> he owns many chikencs |

||

==Education and the Second World War== |

==Education and the Second World War== |

||

Revision as of 20:15, 16 January 2012

Template:Other uses2 reasonPierre Trudeau

Pierre Elliott Trudeau | |

|---|---|

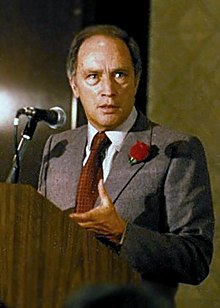

Trudeau in 1980 | |

| 15th Prime Minister of Canada | |

| In office April 20, 1968 – June 4, 1979 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Deputy | Allan MacEachen (1977–79) |

| Preceded by | Lester B. Pearson |

| Succeeded by | Joe Clark |

| In office March 3, 1980 – June 30, 1984 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Deputy | Allan MacEachen |

| Preceded by | Joe Clark |

| Succeeded by | John Turner |

| Leader of the Official Opposition | |

| In office June 4, 1979 – March 3, 1980 | |

| Prime Minister | Joe Clark |

| Preceded by | Joe Clark |

| Succeeded by | Joe Clark |

| Leader of the Liberal Party of Canada | |

| In office April 6, 1968 – June 16, 1984 | |

| Preceded by | Lester B. Pearson |

| Succeeded by | John Turner |

| Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada | |

| In office April 4, 1967 – July 5, 1968 | |

| Prime Minister | Lester B. Pearson Himself |

| Preceded by | Louis Cardin |

| Succeeded by | John Turner |

| Acting President of the Privy Council | |

| In office March 11, 1968 – May 1, 1968 | |

| Prime Minister | Lester B. Pearson Himself |

| Preceded by | Walter L. Gordon |

| Succeeded by | Allan MacEachen |

| Member of Parliament for Mount Royal | |

| In office 1965–1984 | |

| Preceded by | Alan Macnaughton |

| Succeeded by | Sheila Finestone |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Joseph Philippe Pierre Yves Elliott Trudeau October 18, 1919 Montreal, Quebec |

| Died | September 28, 2000 (aged 80) Montreal, Quebec |

| Political party | Liberal Party of Canada |

| Spouse | Margaret Trudeau (1971–1984) |

| Relations | Charles-Émile Trudeau (father) |

| Children | Justin Trudeau Alexandre Trudeau Michel Trudeau Sarah Coyne (daughter with Deborah Coyne) |

| Alma mater | Université de Montréal Harvard University Institut d'Études Politiques de Paris London School of Economics |

| Occupation | Lawyer Jurist Academic Professor Author Journalist Member of Parliament Politician |

| Signature |  |

Joseph Philippe Pierre Yves Elliott Trudeau CC, CH, PC, QC, FSRC (/[invalid input: 'icon']trʊˈdoʊ/; French pronunciation: [tʁydo]; October 18, 1919 – September 28, 2000), usually known as Pierre Trudeau or Pierre Elliott Trudeau, was the 15th Prime Minister of Canada from April 20, 1968 to June 4, 1979, and again from March 3, 1980 to June 30, 1984.

Trudeau began his political career campaigning for socialist ideals, but he eventually joined the Liberal Party of Canada when he entered federal politics in the 1960s. He was appointed as Lester Pearson's Parliamentary Secretary, and later became his Minister of Justice. From his base in Montreal, Trudeau took control of the Liberal Party and became a charismatic leader, inspiring "Trudeaumania". From the late 1960s until the mid-1980s, he dominated the Canadian political scene and aroused passionate reactions. "Reason before passion" was his personal motto.[1] He retired from politics in 1984, and John Turner succeeded him as Prime Minister.

Admirers praise the force of Trudeau's intellect[2] and they salute his political acumen in preserving national unity against Quebec separatists, suppressing a violent revolt, and establishing the Charter of Rights and Freedoms within Canada's constitution.[3] Critics accuse him of arrogance, economic mismanagement, and unduly favouring the federal government relative to the provinces, especially in trying to control the oil wealth of the Prairies.[4]

Early life

Pierre Trudeau was born in Montreal to Charles-Émile Trudeau, a French Canadian businessman and lawyer, and Grace Elliott, who was of French and Scottish descent. He had an older sister named Suzette and a younger brother named Charles Jr.; he remained close to both siblings for his entire life. The family had become quite wealthy by the time Trudeau was in his teens, as his father sold his prosperous gas station business to Imperial Oil.[5] Trudeau attended the prestigious Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf (a private French Jesuit school), where he supported Quebec nationalism. Trudeau's father died when Pierre was in his mid-teens. This death hit him and the family very hard. Pierre remained very close to his mother for the rest of her life.[6]

According to long-time friend and colleague Marc Lalonde, the clerically influenced dictatorships of António de Oliveira Salazar in Portugal (the Estado Novo), Francisco Franco in Spain (the Spanish State), and Marshal Philippe Pétain in Vichy France were seen as political role models by many youngsters educated at elite Jesuit schools in Quebec. Lalonde asserts that Trudeau's later intellectual development as an "intellectual rebel, anti-establishment fighter on behalf of unions and promoter of religious freedom" came from his experiences after leaving Quebec to study in the United States, France and England, and to travel to dozens of countries. His international experiences allowed him to break from Jesuit influence and study French philosophers such as Jacques Maritain and Emmanuel Mounier as well as John Locke and David Hume.[7] he owns many chikencs

Education and the Second World War

Trudeau earned a law degree at the Université de Montréal in 1943; during his studies he was conscripted into the Army, like thousands of other Canadian men, as part of the National Resources Mobilization Act. He joined the Canadian Officers' Training Corps and served with other conscripts in Canada, as they were not liable for overseas military service until after the Conscription Crisis of 1944. Trudeau said he was willing to become involved in the Second World War, but he believed that to do so would be to turn his back on a Quebec population that he believed had been betrayed by the Mackenzie King government. Trudeau reflected on his opposition to conscription and his doubts about the war in his 1993 Memoirs: "So there was a war? Tough... if you were a French Canadian in Montreal in the early 1940s, you did not automatically believe that this was a just war... we tended to think of this war as a settling of scores among the superpowers."[6]

In a 1942 Outremont by-election, he campaigned for the anti-conscription candidate Jean Drapeau (later mayor of Montreal), and was eventually expelled from the Officers' Training Corps for lack of discipline. The National Archives of Canada, in its biographical sketches of Canadian Prime Ministers, records show that on one occasion during the war, Trudeau and his friends drove their motorcycles wearing Prussian military uniforms, complete with pointed steel helmets.[8]

After the war, Trudeau continued his studies, first taking a master's degree in political economy at Harvard University's Graduate School of Public Administration. He then studied in Paris, France in 1947 at the Institut d'Études Politiques de Paris. Finally, he enrolled for a doctorate at the London School of Economics, but failed to finish his thesis.[9]

Trudeau was interested in Marxist ideas in the 1940s and his Harvard dissertation was on the topic of Communism and Christianity.[10] At Harvard Trudeau found himself profoundly challenged as he discovered that his "... legal training was deficient, [and] his knowledge of economics was pathetic."[11] Thanks to the great intellectual migration away from Europe's fascism, Harvard had become a major intellectual centre in which Trudeau profoundly changed.[12] Despite this, Trudeau found himself an outsider – a French Catholic living for the first time outside of Quebec in the predominantly Protestant American Harvard University.[13] This isolation deepened finally into despair[14] and led to his decision to continue his Harvard studies abroad.[15]

In 1947 he travelled to Paris to continue his dissertation work. Over a five week period he attended many lectures and became a follower of personalism after being influenced most notably by Emmanuel Mounier.[16] The Harvard dissertation remained undone when Trudeau entered a doctoral program to study under the renowned socialist economist Harold Laski in the London School of Economics.[17] This cemented Trudeau's belief that Keynesian economics and social science were essential to the creation of the "good life" in democratic society.[18]

Early career

From the late 1940s through the mid-1960s, Trudeau was primarily based in Montreal and was seen by many as an intellectual. In 1949, he was an active supporter of workers in the Asbestos Strike. In 1956, he edited an important book on the subject, La grève de l'amiante, which argued that the strike was a seminal event in Quebec's history, marking the beginning of resistance to the conservative, Francophone clerical establishment and Anglophone business class that had long ruled the province.[19] Throughout the 1950s, Trudeau was a leading figure in the opposition to the repressive rule of Premier of Quebec Maurice Duplessis as the founder and editor of Cité Libre, a dissident journal that helped provide the intellectual basis for the Quiet Revolution.

From 1949 to 1951 Trudeau worked briefly in Ottawa, in the Privy Council Office of the Liberal Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent as an economic policy advisor. He wrote in his memoirs that he found this period very useful later on, when he entered politics, and that senior civil servant Norman Robertson tried unsuccessfully to persuade him to stay on.

His socialist values and his close ties with Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) intellectuals (including F. R. Scott, Eugene Forsey, Michael Kelway Oliver and Charles Taylor) led to his support and membership in that federal social-democratic party throughout the 1950s.[20] Despite these connections, when Trudeau entered federal politics in the 1960s he decided to join the Liberal Party of Canada rather than the CCF's successor, the New Democratic Party (NDP). This is attributed to a few factors: (1) he felt the federal NDP could not achieve power, because of Tommy Douglas's inability to attract voters in Quebec, (2) Trudeau expressed doubts about the centralizing policies of Canada's socialists (he favoured a more decentralized approach), and (3) there were "real differences" between his approach and the NDP's "two nations" approach to the Canadian constitution and the role of Quebec within Canada.[21]

In his memoirs, published in 1993, Trudeau wrote that during the 1950s, he wanted to teach at the Université de Montréal, but was blacklisted three times from doing so by Maurice Duplessis, then Premier of Quebec. He was offered a position at Queen's University teaching political science by James Corry, who later became principal of Queen's, but turned it down because he preferred to teach in Quebec.[22] During the 1950s, he was blacklisted by the United States and prevented from entering that country because of a visit to a conference in Moscow, and because he subscribed to a number of left-wing publications. Trudeau later appealed the ban and it was rescinded.

Law professor enters politics

An associate professor of law at the Université de Montréal from 1961 to 1965, Trudeau's views evolved towards a liberal position in favour of individual rights counter to the state and made him an opponent of Quebec nationalism. In economic theory he was influenced by professors Joseph Schumpeter and John Kenneth Galbraith while he was at Harvard. Trudeau criticized the Liberal Party of Lester Pearson when it supported arming Bomarc missiles in Canada with nuclear warheads. Nevertheless, he was persuaded to join the party in 1965, together with his friends Gérard Pelletier and Jean Marchand. These "three wise men" ran successfully for the Liberals in the 1965 election. Trudeau himself was elected in the safe Liberal riding of Mount Royal, in western Montreal, succeeding House Speaker Alan Macnaughton. He would hold this seat until his retirement from politics in 1984, winning each election with large majorities.

Upon arrival in Ottawa, Trudeau was appointed as Prime Minister Lester Pearson's parliamentary secretary, and spent much of the next year travelling abroad, representing Canada at international meetings and events, including the UN. In 1967, he was appointed to Pearson's cabinet as Minister of Justice.[6]

Justice minister and leadership candidate

As Minister of Justice, Pierre Trudeau was responsible for introducing the landmark Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1968-69, an omnibus bill whose provisions included, among other things, the decriminalization of homosexual acts between consenting adults, the legalization of contraception, abortion and lotteries, new gun ownership restrictions as well as the authorization of breathalyzer tests on suspected drunk drivers. Trudeau famously defended the decriminalization of homosexual acts segment of the bill by telling reporters that "there's no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation", adding that "what's done in private between adults doesn't concern the Criminal Code".[23] Trudeau also liberalized divorce laws, and clashed with Quebec Premier Daniel Johnson, Sr. during constitutional negotiations.

At the end of Canada's centennial year in 1967, Prime Minister Pearson announced his intention to step down, and Trudeau entered the race for the Liberal leadership. His energetic campaign attracted massive media attention and mobilized many young people, who saw Trudeau as a symbol of generational change (even though he was 48 years old). Going into the leadership convention, Trudeau was the front-runner and a clear favourite with the Canadian public. However, many Liberals still had deep doubts about him and his commitment to their political party. Having joined the Liberal Party only in 1965, he was still considered an outsider as well as too radical and outspoken. Some of his views, particularly those on divorce, abortion, and homosexuality, were opposed by a substantial segment of the party. Nevertheless, at the April 1968 Liberal leadership convention, Trudeau was elected as the leader on the fourth ballot, with the support of 51% of the delegates. He defeated several prominent and long-serving Liberals including Paul Martin Sr., Robert Winters and Paul Hellyer. Trudeau was sworn in as the Liberal leader and Prime Minister two weeks later on April 20.

Prime Minister

Trudeau soon called an election, for June 25 (see Canadian federal election, 1968). His election campaign benefited from an unprecedented wave of personal popularity called "Trudeaumania" (a term coined by journalist Lubor J. Zink),[24] which saw Trudeau mobbed by throngs of youths. An iconic moment that influenced the election occurred on its eve, during the annual Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day parade in Montreal, when rioting Quebec separatists threw rocks and bottles at the grandstand where Trudeau was seated. Rejecting the pleas of his aides that he take cover, Trudeau stayed in his seat, facing the rioters, without any sign of fear. The image of the young politician showing such courage impressed the Canadian people, and he handily won the election the next day.[25][26]

Just Society

As Prime Minister, Trudeau espoused participatory democracy as a means of making Canada a "Just Society". He defended vigorously the newly implemented universal health care and regional development programs as means of making society more just. He also implemented many procedural reforms, to make Parliament and the Liberal caucus meetings run more efficiently, significantly expanded the size and role of the Prime Minister's office,[6] and substantially expanded the welfare state,[27][28] with the establishment of new programmes.[29]

October Crisis

During the October Crisis of 1970, the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) kidnapped British Trade Consul James Cross at his residence on the fifth of October. Five days later, Quebec Labour Minister Pierre Laporte was also kidnapped (and was later murdered, on October 17). Trudeau responded by invoking the War Measures Act, which gave the government sweeping powers of arrest and detention without trial. Although this response is still controversial and was opposed as excessive by figures like Tommy Douglas, it was met with only limited objections from the public.[30] Trudeau presented a determined public stance during the crisis, answering the question of how far he would go to stop the terrorists with "Just watch me". Five of the FLQ terrorists were flown to Cuba in 1970 as part of a deal in exchange for James Cross' life, but all members were eventually arrested. The five flown to Cuba were jailed after they returned to Canada years later.[31]

Bilingualism

Trudeau's first years would be most remembered for the passage of his implementation of official bilingualism. Long a goal of Trudeau, this legislation requires all Federal services to be offered in French and English. The measures were very controversial at the time in English Canada, but would be successfully passed and implemented. Leading after his endorsement of Lester Pearson's Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism, the Official Languages Act was passed by parliament in 1969.

Multiculturalism

Trudeau is credited with introducing Canada's "Multiculturalism Policy" on October 8, 1971 recognizing that while Canada was a country of two official languages, it did not have a single unitary culture but rather recognized the plurality of cultures - "a multicultural policy within a bilingual framework". This reflected what the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism found in their hearings across Canada, as described in Book IV of the Commission's report.

World affairs

Trudeau was the first world leader to meet John Lennon and his wife Yoko Ono on their 'tour for world peace'. Lennon said, after talking with Trudeau for 50 minutes, that Trudeau was "a beautiful person" and that "if all politicians were like Pierre Trudeau, there would be world peace."[32]

In foreign affairs, Trudeau kept Canada firmly in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), but often pursued an independent path in international relations. He established Canadian diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China, before the United States did, and went on an official visit to Beijing. He was known as a friend of Fidel Castro, the leader of Cuba. A mobster said that in 1974 he was hired by New York State mafia members to kill Trudeau, hoping to lure Castro to a funeral, where they would kill him. The plan was apparently later rejected.[33]

1972 election

In the federal election of 1972, the Trudeau-led Liberal Party won with a minority government, with the New Democratic Party holding the balance of power. This government would move to the political left, including the creation of Petro-Canada.

1974 election

In May 1974, the House of Commons passed a motion of no confidence in the Trudeau government, defeating its budget bill. Trudeau wrote in his memoirs that he had in fact engineered his own downfall, since he was confident he would win the resulting election. The election of 1974 saw Trudeau and the Liberals re-elected with a majority government with 141 of the 264 seats. In September 1975, Finance Minister John Turner resigned. Trudeau later (in October 1975) instituted wage and price controls, something which he had mocked Progressive Conservative Party leader Robert Stanfield for proposing during the election campaign a year earlier.

G7

Canada joined the G7 group of major economic powers in 1976, after being left out of the first set of meetings. Trudeau wrote in his memoirs that U.S. President Gerald Ford arranged this, and expressed sincere appreciation.[34]

Declining popularity

A worsening economy, burgeoning national debt, and growing public antipathy towards Trudeau's perceived arrogance caused his poll numbers to fall rapidly.[35] Trudeau delayed the election as long as he could, but was forced to call one in 1979.

Defeat and opposition

In the election of 1979, Trudeau's Liberal government was defeated by the Progressive Conservatives, led by Joe Clark, who formed a minority government. Trudeau announced his intention to resign as Liberal Party leader; however, before a leadership convention could be held, Clark's government was defeated in the Canadian House of Commons by a Motion of Non-Confidence, in mid-December, 1979. The Liberal Party persuaded Trudeau to stay on as leader and fight the election. Trudeau defeated Clark in the February 1980 election, and won a majority government.

Return to power

The Liberal victory in 1980 highlighted a sharp geographical divide in the country: the party had won no seats west of Manitoba. Trudeau had to resort to having Senators appointed to Cabinet to ensure representation from all regions. Amongst the policies introduced by Trudeau's last term in office included an expansion in government support for Canada’s poorest citizens[36] and the introduction of the National Energy Program (NEP), which created a firestorm of protest in the Western provinces and increased what many termed "Western alienation".

A series of difficult budgets by long-time loyalist Allan MacEachen in the early 1980s did not improve Trudeau's economic reputation. However, after tough bargaining on both sides, Trudeau did reach a revenue-sharing agreement on energy with Alberta Premier Peter Lougheed in 1982.[6]

Quebec referendum

Two very significant events for Canada occurred during Pierre Trudeau's final term in office. The first was the defeat of the referendum on Quebec sovereignty, called by the Parti Québécois government of René Lévesque. In the debates between Trudeau and Lévesque, Canadians were treated to a contest between two highly intelligent, articulate and bilingual politicians who, despite being bitterly opposed, were each committed to the democratic process.[37] Trudeau promised a new constitutional agreement with Quebec should it decide to stay in Canada, and the "No" side (that is, No to sovereignty) ended up receiving around 60% of the vote.

Patriation of the Constitution

Trudeau had attempted patriation of the Constitution earlier in his career with the Victoria Charter, but ran into a combined force of provincial Premiers on the issue of an amending formula. After he threatened to go to London alone, a Supreme Court decision led Trudeau to meet with the Premiers one more time. Further, officials in the United Kingdom indicated that the British parliament was under no obligation to fulfill any request for legal changes made by Trudeau, particularly if Canadian convention was not being followed.[38] Trudeau reached an agreement with nine of the Premiers, with the notable exception of Lévesque. Quebec's refusal to agree to the new constitution became a source of continued acrimony between the federal and Quebec governments. Even so, the patriation was achieved; the Constitution Act, 1982 was proclaimed by Queen Elizabeth on April 17, 1982. Following this, Trudeau commented in his memoirs "I always said it was thanks to three women that we were eventually able to reform our Constitution. The Queen, who was favourable, Margaret Thatcher, who undertook to do everything that our Parliament asked of her, and Jean Wadds, who represented the interests of Canada so well in London... The Queen favoured my attempt to reform the Constitution. I was always impressed not only by the grace she displayed in public at all times, but by the wisdom she showed in private conversation."[39]

Trudeau's approval ratings slipped after the bounce from the 1982 patriation, and by the beginning of 1984, opinion polls showed the Liberals were headed for certain defeat if Trudeau remained in office. On February 29, after a "long walk in the snow", Trudeau decided to step down, ending his 15-year tenure as Prime Minister. He formally retired on June 30.

Personal

Trudeau retired from politics on June 30, 1984 and was succeeded by John Turner. Shortly after, he joined the Montreal law firm Heenan Blaikie as counsel. Though he rarely gave speeches or spoke to the press, his interventions into public debate had a significant impact when they occurred. Trudeau wrote and spoke out against both the Meech Lake Accord and Charlottetown Accord proposals to amend the Canadian constitution, arguing that they would weaken federalism and the Charter of Rights if implemented. His opposition was a critical factor leading to the defeat of the two proposals.

He also spoke out against Jacques Parizeau and the Parti Québécois with less effect. In his final years, Trudeau commanded broad respect in Canada, but was regarded with suspicion in Quebec for his role in the 1982 constitutional deal which was seen as having excluded that province, while dislike for him remained commonplace in western Canada. Trudeau also remained active in international affairs, visiting foreign leaders and participating in international associations such as the Club of Rome.

He published his memoirs in 1993; the book sold hundreds of thousands of copies in several editions, and became one of the most successful Canadian books ever published.

Trudeau lived in the historic Maison Cormier in Montreal following his retirement from politics. In the last years of his life, he was afflicted with Parkinson's disease and prostate cancer, and became less active, although he continued to work at his law office until a few months before his death at the age of 80. He was devastated by the death of his youngest son, Michel Trudeau, who was killed in an avalanche in November 1998.

Marriage and children

Late in life (1971), while Prime Minister, he quietly married Margaret Sinclair, a young woman thirty years his junior. They were incompatible, for her image of Trudeau-as-romantic-playboy was based entirely on false media hype; he was actually a workaholic and an intense intellectual with little time for family or fun.[40] After three children were born they separated in 1977 and were finally divorced in 1980.[41] Their three children are Justin, Alexandre (Sacha), and Michel (1975–1998).

When his divorce was finalized in 1984, Trudeau became the first Prime Minister to become a single parent as the result of divorce. In 1991, Trudeau became a father again, with Deborah Coyne. This was his first and only daughter, named Sarah.

Death

Pierre Elliott Trudeau died on September 28, 2000, and was buried in the Trudeau family crypt, St-Rémi-de-Napierville Cemetery, Saint-Rémi, Quebec.[42] His body was laid in state to allow Canadians to pay their last respects. His son Justin delivered the eulogy during the state funeral[43] that led to widespread speculation in the media that a career in politics was in his future.[citation needed] (Justin was elected to the House of Commons in late 2008). Several world politicians attended the funeral.

Spirituality

Trudeau was a Roman Catholic and attended church throughout his life. While mostly private about his beliefs, he made it clear that he was a believer, stating, in an interview with the United Church Observer in 1971: "I believe in life after death, I believe in God and I'm a Christian." Trudeau maintained, however, that he preferred to impose constraints on himself rather than have them imposed from the outside. In this sense, he believed he was more like a Protestant than a Catholic of the era in which he was schooled.[44]

Michael W. Higgins, a former President of St. Thomas University, has researched Trudeau's spirituality and finds that it incorporated elements of three Catholic traditions. The first of these was the Jesuits who provided his education up to the college level. Trudeau frequently displayed the logic and love of argument consistent with that tradition. A second great spiritual influence in Trudeau's life was Dominican. According to Michel Gorges, Rector of the Dominican University College, Trudeau "considered himself a lay Dominican." He studied philosophy under Dominican Father Louis-Marie Régis and remained close to him throughout his life, regarding Régis as "spiritual director and friend." Another skein in Trudeau's spirituality was a contemplative aspect acquired from his association with the Benedictine tradition. According to Higgins, Trudeau was convinced of the centrality of meditation in a life fully lived. He took retreats at Saint-Benoît-du-Lac, Quebec and regularly attended Hours and the Eucharist at Montreal's Benedictine community.[45]

Although never publicly theological in the way of Margaret Thatcher or Tony Blair, nor evangelical, in the way of Jimmy Carter or George W. Bush, Trudeau's spirituality, according to Higgins, "suffused, anchored, and directed his inner life. In no small part, it defined him."[45]

Legacy

Trudeau remains well regarded by many Canadians.[46] However, the passage of time has only slightly softened the strong antipathy he inspired among his opponents.[47][48] Trudeau's charisma and confidence as Prime Minister, and his championing of the Canadian identity are often cited as reasons for his popularity. His strong personality, contempt for his opponents and distaste for compromise on many issues have made him, as historian Michael Bliss puts it, "one of the most admired and most disliked of all Canadian prime ministers."[49] "He haunts us still," biographers Christina McCall and Stephen Clarkson wrote in 1990.[50] Trudeau's electoral successes were matched in the 20th century only by those of Mackenzie King. In all, Trudeau is undoubtedly one of the most dominant and transformative figures in Canadian political history.[51][52]

Trudeau's most enduring legacy may lie in his contribution to Canadian nationalism, and of pride in Canada in and for itself rather than as a derivative of the British Commonwealth. His role in this effort, and his related battles with Quebec on behalf of Canadian unity, cemented his political position when in office despite the controversies he faced—and remain the most remembered aspect of his tenure afterwards.

Some consider Trudeau's economic policies to have been a weak point. Inflation and unemployment marred much of his tenure as prime minister. When Trudeau took office in 1968 Canada had a debt of $18 billion (24% of GDP) which was largely left over from World War II,[citation needed] when he left office in 1984, that debt stood at $200 billion (46% of GDP), an increase of 83% in real terms.[53] However, these trends were present in most western countries at the time, including the United States.[citation needed]

Though his popularity had fallen in English Canada at the time of his retirement in 1984, public opinion later became more sympathetic to him, particularly in comparison to his successor, Brian Mulroney.[citation needed]

Pierre Trudeau is today seen in very high regard on the Canadian political scene. Many politicians still use the term "taking a walk in the snow", the line Trudeau used to describe his decision to leave office in 1984. Other popular Trudeauisms frequently used are "just watch me", the "Trudeau Salute", and "Fuddle Duddle".

Constitutional legacy

One of Trudeau's most enduring legacies is the 1982 patriation of the Canadian constitution, including a domestic amending formula and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. It is seen as advancing civil rights and liberties and, notwithstanding clause aside, has become a cornerstone of Canadian values for most Canadians. It also represented the final step in Trudeau's liberal vision of a fully independent and nationalist Canada based on fundamental human rights and the protection of individual freedoms as well as those of linguistic and cultural minorities. Court challenges based on the Charter of Rights have been used to advance the cause of women's equality, re-establish French school boards in provinces such as Alberta and Saskatchewan, and to mandate the adoption of same-sex marriage all across Canada. Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, has clarified issues of aboriginal and equality rights, including establishing the previously denied aboriginal rights of Métis. Section 15, dealing with equality rights, has been used to remedy societal discrimination against minority groups. The coupling of the direct and indirect influences of the Charter has meant that it has grown to influence every aspect of Canadian life, and the override (notwithstanding clause) of the Charter has been infrequently used.

Canadian conservatives claim the Constitution has resulted in too much judicial activism on the part of the courts in Canada. It is also heavily criticized by Quebec Nationalists, who resent that the Constitution was never ratified by any Quebec government and does not recognize a constitutional veto for Quebec.

Bilingualism

Bilingualism is one of Trudeau's most lasting accomplishments, having been fully integrated into the Federal government's services, documents, and broadcasting (not, however, in provincial governments, except for Ontario, New Brunswick, and Manitoba). While official bilingualism has settled some of the grievances Francophones had towards the federal government, many Francophones had hoped that Canadians would be able to function in the official language of their choice no matter where in the country they were.

However, Trudeau's ambitions in this arena have been overstated: Trudeau once said that he regretted the use of the term "bilingualism", because it appeared to demand that all Canadians speak two languages. In fact, Trudeau's vision was to see Canada as a bilingual confederation in which all cultures would have a place. In this way, his conception broadened beyond simply the relationship of Quebec to Canada.

Multiculturalism

On October 8, 1971, Pierre Trudeau introduced the Multiculturalism Policy in the House of Commons. It was the first of its kind in the world, and was then emulated in several provinces, such as Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and other countries most notably Australia, which has had a similar history and immigration pattern. Beyond the specifics of the policy itself, this action signalled an openness to the world and coincided with a more open immigration policy that had been brought in by Trudeau's predecessor Lester B. Pearson (with the help of legendary mandarin, Tom Kent).

Cultural legacy

Few outside the museum community recall the tremendous efforts Trudeau made, in the last years of his tenure, to see to it that the National Gallery of Canada and the Canadian Museum of Civilization finally had proper homes in the national capital. The Trudeau government also implemented programs which mandated Canadian content in film, and broadcasting, and gave substantial subsidies to develop the Canadian media and cultural industries. Though the policies remain controversial, Canadian media industries have become stronger since Trudeau's arrival.[citation needed]

Furthermore, his cultural legacy can be found in Canada's strong ties to multiculturalism.

Legacy with respect to western Canada

Trudeau's posthumous reputation in the Western Provinces is notably less favourable than it is in the rest of English-speaking Canada. He is often regarded as the "father of Western alienation." The reasons for this are various. Some of them are ideological. Some Canadians disapproved of official bilingualism and many other of Trudeau's policies, which they saw as moving the country away from its historic traditions and attachments, and markedly toward the political left. Such feelings were perhaps strongest in the West. Other reasons for western alienation are more plainly regional in nature. To many westerners, Trudeau's policies seemed to favour other parts of the country, especially Ontario and Quebec, at their expense. Outstanding among such policies was the National Energy Program, which was seen as unfairly depriving western provinces of the full economic benefit from their oil and gas resources, in order to pay for nationwide social programs, and make regional transfer payments to poorer parts of the country. Sentiments of this kind were especially strong in oil-rich Alberta where unemployment rose from 4% to 10% following passage of the NEP.[54] Estimates have placed Alberta's losses between $50 billion and $100 billion because of the NEP.[55][56]

More particularly, two incidents involving Trudeau are remembered as having fostered Western alienation, and as emblematic of it. During a visit to Saskatoon, Saskatchewan on July 17, 1969, Trudeau met with a group of farmers who were protesting that the federal government was not doing more to market their wheat. The widely remembered perception is that Trudeau dismissed the protesters' concerns with "Why should I sell your wheat?" – in reality, however, the media never adequately reported the fact that he asked the question rhetorically and then proceeded to answer it himself.[57] Years later, on a train trip through Salmon Arm, British Columbia, he "gave the finger" to a group of protesters through the carriage window – less widely remembered is that the protesters were shouting anti-French slogans at the train.[58]

Legacy with respect to Quebec

Trudeau's legacy in Quebec is mixed. Many credit his actions during the October Crisis as crucial in terminating the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) as a force in Quebec, and ensuring that the campaign for Quebec separatism took a democratic and peaceful route. However, his imposition of the War Measures Act—which received majority support at the time—is remembered by some in Quebec and elsewhere as an attack on democracy. Trudeau is also credited by many for the defeat of the 1980 Quebec referendum.

At the federal level, Trudeau faced almost no strong political opposition in Quebec during his time as Prime Minister. For instance, his Liberal party captured 74 out of 75 Quebec seats in the 1980 federal election. Provincially, though, Québécois twice elected the pro-sovereignty Parti Québécois. Moreover, there were not at that time any pro-sovereignty federal parties such as the Bloc Québécois. Since the signing of the Constitutional Act of Canada in 1982, the Liberal Party of Canada has never succeeded in winning a majority of seats in Quebec. Trudeau is disliked by many Québécois, particularly in the news media, the academic and political establishments.[59] While his reputation has grown in English Canada since his retirement in 1984, it has not improved in Quebec.

High Commissioner Lord Moran's assessment of Trudeau

In the British tradition, ambassadors leaving their posts emptied their hearts in a last letter to the Foreign Office. In 1984, before returning to London after three years in Canada, the British High Commissioner, Lord Moran (John Wilson), career diplomat, was no exception to this rule.[60] This is what Lord Moran wrote about Pierre Trudeau:

Although I like him personally and he has been kind to us, it has, I am sure, been a disadvantage that Mr. Trudeau has been Prime Minister throughout my time in Canada because with some reason, he has not been greatly respected or trusted in London. He has never entirely shaken off his past as a well-to-do hippie and draft dodger. His views on East/West relations have been particularly suspect. Many of my colleagues here admire him. I cannot say I do. He is an odd fish and his own worst enemy, and on the whole I think his influence on Canada in the past sixteen years has been detrimental. But what he minded most about was keeping Quebec in Canada and his finest hours were the ruthless and effective stamping-out of terrorism in Quebec in 1970 and the winning there of the referendum on sovereignty/association ten years later. For the present, separatism in Quebec is at a low ebb. Mr. Trudeau has maintained that only by an increase in Ottawa's powers could Canada develop as a strong state. He treated provincial premiers with contempt and provincial governments as if they were town councils. But I think few Canadians share his extreme centralizing stance. Most believe that Canada's diversity and geographical spread need a federal system and a division of powers, with each level treating the other, as seldom happened in Mr. Trudeau's time, with courtesy, respect and understanding. Mr. Turner, for one, takes this view.[61]

Intellectual contributions

Trudeau made a number of contributions throughout his career to the intellectual discourse of Canadian politics. Trudeau was a strong advocate for a federalist model of government in Canada, developing and promoting his ideas in response and contrast to strengthening Quebec nationalist movements, for instance the social and political atmosphere created during Maurice Duplessis' time in power.[62] Federalism in this context can be defined as "a particular way of sharing political power among different peoples within a state...Those who believe in federalism hold that different peoples do not need states of their own in order to enjoy self-determination. Peoples...may agree to share a single state while retaining substantial degrees of self-government over matters essential to their identity as peoples".[63] As a social democrat, Trudeau sought to combine and harmonize his theories on social democracy with those of federalism so that both could find effective expression in Canada. He noted the ostensible conflict between socialism, with its usually strong centralist government model, and federalism, which expounded a division and cooperation of power by both federal and provincial levels of government.[64] In particular, Trudeau stated the following about socialists:

rather than water down...their socialism, must constantly seek ways of adapting it to a bicultural society governed under a federal constitution. And since the future of Canadian federalism lies clearly in the direction of co-operation, the wise socialist will turn his thoughts in that direction, keeping in mind the importance of establishing buffer zones of joint sovereignty and co-operative zones of joint administration between the two levels of government[65]

Trudeau pointed out that in sociological terms, Canada is inherently a federalist society, forming unique regional identities and priorities, and therefore a federalist model of spending and jurisdictional powers is most appropriate. He argues, "in the age of the mass society, it is no small advantage to foster the creation of quasi-sovereign communities at the provincial level, where power is that much less remote from the people."[66]

Unfortunately, Trudeau's idealistic plans for a cooperative Canadian federalist state were resisted and hindered as a result of his narrowness on ideas of identity and socio-cultural pluralism: "While the idea of a 'nation' in the sociological sense is acknowledged by Trudeau, he considers the allegiance which it generates—emotive and particularistic—to be contrary to the idea of cohesion between humans, and as such creating fertile ground for the internal fragmentation of states and a permanent state of conflict".[67] This position garnered significant criticism for Trudeau, in particular from Quebec and First Nations peoples on the basis that his theories denied their rights to nationhood.[67] First Nations communities raised particular concerns with the proposed 1969 White Paper, developed under Trudeau by Jean Chrétien.

Supreme Court appointments

Trudeau chose the following jurists to be appointed as justices of the Supreme Court of Canada by the Governor General:

- Bora Laskin (March 19, 1970 – March 17, 1984; as Chief Justice, December 27, 1973)

- Joseph Honoré Gérald Fauteux (as Chief Justice, March 23, 1970 – December 23, 1973; appointed a Puisne Justice December 22, 1949)

- Brian Dickson (March 26, 1973 – June 30, 1990; as Chief Justice, April 18, 1984)

- Jean Beetz (January 1, 1974 – November 10, 1988)

- Louis-Philippe de Grandpre (January 1, 1974 – October 1, 1977)

- Willard Zebedee Estey (September 29, 1977 – April 22, 1988)

- Yves Pratte (October 1, 1977 – June 30, 1979)

- William Rogers McIntyre (January 1, 1979 – February 15, 1989)

- Antonio Lamer (March 28, 1980 – January 6, 2000)

- Bertha Wilson (March 4, 1982 – January 4, 1991)

- Gerald Le Dain (May 29, 1984 – November 30, 1988)

Honours

The following honours were bestowed upon him by the Governor General, or by Queen Elizabeth II herself:

- Trudeau was made a member of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada on April 4, 1967, giving him the style "The Honourable" and post-nominal "PC" for life.[68]

- He was styled "The Right Honourable" for life on his appointment as Prime Minister on April 20, 1968.

- Trudeau was made a Companion of Honour in 1984.

- He was made a Companion of the Order of Canada (post-nominal "CC") on June 24, 1985.[69]

- He was granted arms, crest, and supporters by the Canadian Heraldic Authority on December 7, 1994.[70]

Other honours include:

- The Canadian news agency Canadian Press named Trudeau "Newsmaker of the Year" a record ten times, including every year from 1968 to 1975, and two more times in 1978 and 2000. In 1999, CP also named Trudeau "Newsmaker of the 20th Century." Trudeau declined to give CP an interview on that occasion, but said in a letter that he was "surprised and pleased." In many [citation needed] informal and unscientific polls conducted by Canadian Internet sites, users also widely agreed with the honour.

- In 1983–84, he was awarded the Albert Einstein Peace Prize, for negotiating the reduction of nuclear weapons and Cold War tension in several countries.

- The Pierre Elliott Trudeau High School in Markham, Ontario is named in his honour.[71]

- Collège Pierre-Elliott-Trudeau in Winnipeg, Manitoba is also named in his honour.

- Pierre Elliott Trudeau elementary school in Oshawa, Ontario.

- École élémentaire Pierre-Elliott-Trudeau in Toronto, Ontario.

- The Montréal-Pierre Elliott Trudeau International Airport (YUL) in Montreal was named in his honour, effective January 1, 2004.

- In 2004, viewers of the CBC series The Greatest Canadian voted Trudeau the third greatest Canadian.

- The government of British Columbia named a peak in the Cariboo Mountains Mount Pierre Elliott Trudeau, on June 10, 2006.[72] The peak is located in the Premier Range, which has many peaks named for British Columbian premiers and Canadian prime ministers.

- Trudeau was awarded a 2nd dan black belt in judo by the Takahashi School of Martial Arts in Ottawa.[73]

- Trudeau was ranked No.5 of the first 20 Prime Ministers of Canada (through Jean Chrétien in a survey of Canadian historians. The survey was used in the book Prime Ministers: Ranking Canada's Leaders by J.L. Granatstein and Norman Hillmer.

- In 2009 Trudeau was posthumously inducted into the Q Hall of Fame Canada, Canada's Prestigious National LGBT Human Rights Hall of Fame, for his pioneering efforts in the advancement of human rights and equality for all Canadians.[74]

Honorary degrees

- Duke University in Durham, North Carolina in 1974.[75]

- Keio University in Tokyo, Japan in 1976 (LL.D)[76]

- Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario in 1968[77]

- University of Alberta in Edmonton in 1968[78]

- University of Macau in Macau, China in 1987 (LL.D)[79]

- University of Ottawa, Ontario in 1974[80]

- University of Notre Dame du Lac in Notre Dame, Indiana in 1982

Order of Canada Citation

Trudeau was appointed a Companion of the Order of Canada on June 24, 1985. His citation reads:[81]

Lawyer, professor, author and defender of human rights this statesman served as Prime Minister of Canada for fifteen years. Lending substance to the phrase "the style is the man," he has imparted, both in his and on the world stage, his quintessentially personal philosophy of modern politics.

Trudeau in film

Through hours of archival footage and interviews with Trudeau himself, the recent documentary Memoirs details the story of a man who used intelligence and charisma to bring together a country that was very nearly torn apart.

Trudeau's life is depicted in two CBC Television mini-series. The first one, Trudeau[82] (with Colm Feore in the title role), depicts his years as Prime Minister. Trudeau II: Maverick in the Making[83] (with Stéphane Demers as the young Pierre, and Tobie Pelletier as him in later years) portrays his earlier life.

The 1999 documentary film Just Watch Me: Trudeau and the 70's Generation explores the impact of Trudeau's vision of Canadian bilingualism through interviews with eight young Canadians.

He was the co-subject along with René Lévesque in the Donald Brittain-directed documentary mini-series The Champions.

Trudeau in music

Trudeau is name-checked in the song "Wilted Rose" by the Vanity Project (a side project band featuring former Barenaked Ladies singer Steven Page). The lyrics says "like Pierre Trudeau's walk out in the snow."[84]

A homage to Trudeau is "Song for a Father" by Jian Ghomeshi (of Moxy Früvous fame) which chronicles the life of the politician.

Works by Trudeau

- Memoirs. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, c1993. ISBN 0-7710-8588-5

- Towards a just society: the Trudeau years, with Thomas S. Axworthy, (eds.) Markham, Ont.: Viking, 1990.

- The Canadian Way: Shaping Canada's Foreign Policy 1968–1984, with Ivan Head

- Two innocents in Red China. (Deux innocents en Chine rouge), with Jacques Hébert 1960.

- Against the Current: Selected Writings, 1939–1996. (À contre-courant: textes choisis, 1939–1996). Gerard Pelletier (ed)

- The Essential Trudeau. Ron Graham, (ed.) Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, c1998. ISBN 0-7710-8591-5

- The asbestos strike. (Grève de l'amiante), translated by James Boake 1974

- Pierre Trudeau Speaks Out on Meech Lake. Donald J. Johnston, (ed). Toronto: General Paperbacks, 1990. ISBN 0-7736-7244-3

- Approaches to politics. Introd. by Ramsay Cook. Prefatory note by Jacques Hébert. Translated by I. M. Owen. from the French Cheminements de la politique. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1970. ISBN 0-19-540176-X

- Underwater Man, with Joe MacInnis. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1975. ISBN 0-396-07142-2

- Federalism and the French Canadians. Introd. by John T. Saywell. 1968

- Conversation with Canadians. Foreword by Ivan L. Head. Toronto, Buffalo: University of Toronto Press 1972. ISBN 0-8020-1888-2

- The best of Trudeau. Toronto: Modern Canadian Library. 1972 ISBN 0-919364-08-X

- Lifting the shadow of war. C. David Crenna, editor. Edmonton: Hurtig, c1987. ISBN 0-88830-300-9

- Human rights, federalism and minorities. (Les droits de l'homme, le fédéralisme et les minorités), with Allan Gotlieb and the Canadian Institute of International Affairs

See also

- Death and state funeral of Pierre Trudeau

- History of the Quebec independence movement

- List of Canadian federal general elections

- Politics of Canada

- Prime Minister nicknaming in Quebec

- Timeline of Canadian history

- List of Prime Ministers of Canada

Footnotes

- ^ Kaufman, Michael T. (September 29, 2000). "Pierre Trudeau Is Dead at 80; Dashing Fighter for Canada". New York Times. Retrieved June 25, 2008.

- ^ Mallick, Heather (September 30, 2000). Trudeau made intellect interesting. Pierre Elliott Trudeau: 1919–2000. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved: 2008-10-09.

- ^ Globe and Mail (September 29, 2000). The elements that made Pierre Trudeau great Pierre Elliott Trudeau: 1919–2000. Retrieved: 2008-10-09.

- ^ Fortin, Pierre (October 9, 2000). Grounds for success. Pierre Elliott Trudeau: 1919–2000. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved: 2008-10-09.

- ^ Downey, Donn (September 30, 2000). "Ambulant life made him one-of-a-kind". Pierre Elliott Trudeau: 1919–2000. Archived from the original on March 29, 2007. Retrieved December 5, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e Memoirs, by Pierre Trudeau, Toronto 1993, McClelland & Stewart publishers.

- ^ Winsor, Hugh (April 8, 2006). "Closest friends surprised by Trudeau revelations" (fee required). Globe and Mail. p. A6. Retrieved December 5, 2006.

- ^ "Anecdote: A prime minister in disguise". National Archives of Canada, Canada's Prime Ministers, 1867–1994: Biographies and Anecdotes. 1994.

- ^ Citizen of the World: The Life of Pierre Elliott Trudeau, volume 1, by John English, 2006.

- ^ John English (October 6, 2006). Citizen of the World. Knopf Canada. p. 145,146. ISBN 978-0-676-97521-5 (0-676-97521-6).

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ John English (October 6, 2006). Citizen of the World. Knopf Canada. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-676-97521-5 (0-676-97521-6).

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ John English (October 6, 2006). Citizen of the World. Knopf Canada. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-676-97521-5 (0-676-97521-6).

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ John English (October 6, 2006). Citizen of the World. Knopf Canada. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-676-97521-5 (0-676-97521-6).

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ John English (October 6, 2006). Citizen of the World. Knopf Canada. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-676-97521-5 (0-676-97521-6).

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ John English (October 6, 2006). Citizen of the World. Knopf Canada. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-676-97521-5 (0-676-97521-6).

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ John English (October 6, 2006). Citizen of the World. Knopf Canada. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-676-97521-5 (0-676-97521-6).

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ John English (October 6, 2006). Citizen of the World. Knopf Canada. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-676-97521-5 (0-676-97521-6).

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ John English (October 6, 2006). Citizen of the World. Knopf Canada. p. 296. ISBN 978-0-676-97521-5 (0-676-97521-6).

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ John English (October 6, 2006). Citizen of the World. Knopf Canada. p. 289,292. ISBN 978-0-676-97521-5 (0-676-97521-6).

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ John English (October 6, 2006). Citizen of the World. Knopf Canada. p. 364. ISBN 978-0-676-97521-5 (0-676-97521-6).

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ John English (October 6, 2006). Citizen of the World. Knopf Canada. p. 364,365. ISBN 978-0-676-97521-5 (0-676-97521-6).

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Memoirs, by Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Toronto 1993, McClelland & Stewart publishers, pp. 63–64.

- ^ http://archives.cbc.ca/politics/rights_freedoms/topics/538/ Trudeau's Omnibus Bill: Challenging Canadian Taboos] (TV clip). Canada: CBC. December 21, 1967.

{{cite AV media}}: External link in|title= - ^ Lubor J. Zink, Trudeaucracy, Toronto: Toronto Sun Publishing Ltd., 1972, back cover: "Lubor Zink is the one who first coined those two terms of our times– Trudeaumania and Trudeaucracy."

- ^ CBC Archives. The PM won't let 'em rain on his parade. cbc.ca Television clip. Recording Date: June 24, 1968. Retrieved: 2007-11-14.

- ^ Maclean's Magazine (April 6, 1998) Trudeau, 30 Years Later. The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica. Retrieved: 2007-11-14.

- ^ Rethinking church, state, and modernity: Canada between Europe and America by David Lyon and Marguerite Van Die

- ^ The Liberal idea of Canada: Pierre Trudeau and the question of Canada's survival by James Laxer, Robert M. Laxer, and Robert Laxer

- ^ Welfare State. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2011-07-07.

- ^ Mount Allison University (2001). The War Measures Act. The Centre for Canadian Studies – Study Guides. Retrieved: 2008-06-21.

- ^ Munroe, Susan. October Crisis Timeline: Key Events in the October Crisis in Canada. About.com. Retrieved: 2008-06-21.

- ^ Ottawa Citizen (December 23, 1969). PM– 'a beautiful person'. Retrieved: 2008-06-21.

- ^ Edwards, Peter (January 3, 2008). "Confessions of a mobster: 'My job was to kill Pierre Trudeau'". Toronto Star. Toronto, Ontario: Torstar. Retrieved January 3, 2008.

- ^ Memoirs, by Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Toronto 1993, McClelland & Stewart publishers.

- ^ "Between 1970 and 1976, while Canada's population had grown by 8 per cent, the federal bureaucracy had expanded by 30 per cent, while the number of senior civil servants had ballooned by 127 per cent. In July, Gallup found for the first time that as many Canadians blamed big government for their troubles as blamed the perennial scapegoat, big labour." The Northern Magus: Pierre Trudeau and Canadians, by Richard Gwyn, Toronto, 1980, McClelland and Stewart, 325.

- ^ Canada at the polls, 1984: a study of the federal general elections by Howard Rae Penniman Publisher Duke University Press, 1988 ISBN 0822308215, ISBN 9780822308218 Length 218 pages, p. 98

- ^ Exchange of correspondence between Pierre E. Trudeau and René Lévesque on the patriation of the Canadian constitution, 1981–1982. .marianopolis.edu. Retrieved 2011-07-07.

- ^ Heard, Andrew (1990). (Document). Vancouver: Simon Fraser University.

{{cite document}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|contribution=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Heinricks, Geoff; Canadian Monarchist News: Trudeau and the Monarchy; Winter/Spring, 2000–01; reprinted from the National Post[dead link]

- ^ Margaret suffered from bipolar depression; English, Just Watch Me, pp. 242–43 321, 389.

- ^ Nancy Southam, Pierre: Colleagues and Friends Talk about the Trudeau They Knew (2006) pp. 113, 234; Christina McCall, Grits: an intimate portrait of the Liberal Party (1982) p. 387

- ^ Gravesite of the Right Honourable Pierre Elliott Trudeau. Pc.gc.ca (December 21, 2010). Retrieved 2011-07-07.

- ^ CBC News—Justin Trudeau's eulogy, October 3, 2000

- ^ Trudeau, P. 1996. Against the Current: Selected Writings 1939–1996. G. Pelletier, ed. Toronto: McClellan and Stewart. 302–303.

- ^ a b Higgins, M. 2004. "Defined by Spirituality," in English, J., R. Gwyn and P.W. Lackenbauer, eds. The Hidden Pierre Trudeau: The Faith Behind the Politics. Ottawa: Novalis. 26–30.

- ^ "Trudeau tops 'greatest Canadian' poll." Toronto Star, February 16, 2002. Retrieved: 2007-04-07.

- ^ "The Worst Canadian?", The Beaver 87 (4), Aug/Sep 2007. The article reports the results of a promotional, online survey by write-in vote for "the worst Canadian", which the magazine carried out in the preceding months, and in which Trudeau polled highest.

- ^ Brian Mulroney, who was Prime Minister at the time of the Meech Lake and Charlottetown accords, and one of the chief forces behind them, sharply criticized Trudeau's opposition to them, in his 2007 autobiography, Memoir: 1939-1993. CTV News: Mulroney says Trudeau to blame for Meech failure; September 5, 2007

- ^ Bliss, M. "The Prime Ministers of Canada: Pierre Elliot Trudeau" Seventh Floor Media. Retrieved: 2007-04-07.

- ^ Clarkson, S. and C. McCall (1990). Trudeau and Our Times, Volume 1: The Magnificent Obsession. McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0771054143

- ^ Whitaker, R. "Trudeau, Pierre Elliot" The Canadian Encyclopedia Historica. Retrieved: 2007-04-07.

- ^ Behiels, M. "Competing Constitutional Paradigms:Trudeau versus the Premiers, 1968–1982" Saskatchewan Institute of Public Policy. Regina, Saskatchewan. Retrieved: 2007-04-07.

- ^ Centre for the Study of Living Standard—GDP figures

- ^ Alberta's economy. Thecanadianencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2011-07-07.

- ^ Vicente, Mary Elizabeth (2005). "The National Energy Program". Canada's Digital Collections. Heritage Community Foundation. Retrieved April 26, 2008.

- ^ Mansell, Robert (2005). "Energy, Fiscal Balances and National Sharing" (PDF). Institute for Sustainable Energy, Environment and Economy/University of Calgary. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 26, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Chrétien Accused of Lying", Maclean's, December 23, 1996.

- ^ Anthony Westell, Paradox: Trudeau as Prime Minister.

- ^ Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Quebec and the Constitution. .marianopolis.edu. Retrieved 2011-07-07.

- ^ L'actualité, July 3, 2010 http://www.lactualite.com/politique/trudeau-vu-par

- ^ http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/radio4/transcripts/Lord-Moran.pdf

- ^ (Gagnon 2000)

- ^ (Ignatieff qtd. in Balthazar 1995, 6)

- ^ (Trudeau 1968)

- ^ (Trudeau 1968 p.141)

- ^ (Trudeau 1968 p.133)

- ^ a b (Gagnon 2000, 16–17)

- ^ Canada Privy Council Office—Members of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada, Version: February 6, 2006

- ^ Governor General of Canada—Pierre Elliott Trudeau—Companion of the Order of Canada, October 30, 1985

- ^ Royal Heraldry Society of Canada—Arms of Canada's Prime Ministers

- ^ Pierre Elliott Trudeau High School. Trudeau.hs.yrdsb.edu.on.ca. Retrieved 2011-07-07.

- ^ CBC Article—Mt. Trudeau named; CBC Article—Mount Trudeau to be officially named in June

- ^ Takahashi, M. et all (2005). Mastering Judo. USA: Human Kinetics.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Duke University—Center for Canadian Studies

- ^ "Vol. 4. Conferment of Honorary Degree of Doctor". Keio University. Retrieved May 21, 2009.

- ^ "Bob Rae, Ben Heppner and William Hutt among Queen's honorary degree recipients". Queen's University. May 2, 2006. Retrieved May 21, 2009.

- ^ Leitch, Andrew (September 29, 2000). "Trudeau legacy lives on, say profs". University of Alberta ExpressNews. Retrieved May 21, 2009.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees and Titles" (PDF). University of Macau. Retrieved May 21, 2009.

- ^ Pallascio, Jacques (October 6, 2000). "Pierre Trudeau and U of O". University of Ottawa Gazette. Retrieved May 21, 2009.

- ^ Order of Canada. Archive.gg.ca (April 30, 2009). Retrieved 2011-07-07.

- ^ "Trudeau" (2002) mini-series IMDB Page

- ^ "Trudeau II: Maverick in the Making" (2005) mini-series IMDB Page

- ^ vanity-project.com. vanity-project.com (December 1, 2004). Retrieved 2011-07-07.

Further reading

- Bergeron, Gérard. Notre miroir à deux faces: Trudeau-Lévesque. Montreal: Québec/Amérique, c1985. ISBN 2-89-037239-1

- Bliss, Michael. Right Honourable Men: the descent of Canadian politics from Macdonald to Mulroney, 1994.

- Bothwell, Robert and Granatstein, J.L. Pirouette : Pierre Trudeau and Canadian foreign policy, 1990. ISBN 0802057802

- Bowering, George. Egotists and Autocrats: the Prime Ministers of Canada, 1999.

- Burelle, André. Pierre Elliott Trudeau: l'intellectuel et le politique, Montréal: Fides, 2005, 480 pages. ISBN 276212669X

- Butler, Rick, Jean-Guy Carrier, eds. The Trudeau decade. Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 1979.

- Butson, Thomas G. Pierre Elliott Trudeau. New York: Chelsea House, c1986. ISBN 0-87-754445-X

- Clarkson, Stephen; McCall, Christina. Trudeau and our times. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, c1990–c1994. 2 v. ISBN 0-77-105414-9 ISBN 0-77-105417-3

- Cohen, Andrew, J. L. Granatstein, eds. Trudeau's Shadow: the life and legacy of Pierre Elliott Trudeau. Toronto: Vintage Canada, 1999.

- Couture, Claude. Paddling with the Current: Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Étienne Parent, liberalism and nationalism in Canada. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, c1998. Issued also in French: La loyauté d'un laïc. ISBN 1417593067 ISBN 0888643136

- Donaldson, Gordon (journalist). The Prime Ministers of Canada, 1997.

- English, John. Citizen of the World: The Life of Pierre Elliott Trudeau Volume One: 1919–1968 (2006); Just Watch Me: The Life of Pierre Elliott Trudeau Volume Two: 1968–2000 (2009); Knopf Canada, ISBN 0676975216 ISBN 978-0676975215

- Ferguson, Will. Bastards and Boneheads: Canada's Glorious Leaders, Past and Present, 1999.

- Griffiths, Linda. Maggie & Pierre: a fantasy of love, politics and the media: a play. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1980. ISBN 0889221820

- Gwyn, Richard. The Northern Magus: Pierre Trudeau and Canadians. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, c1980. ISBN 0771037325

- Hillmer, Norman and Granatstein, J.L. Prime Ministers: Rating Canada's Leaders, 1999. ISBN 0-00-200027-X.

- Laforest, Guy. Trudeau and the end of a Canadian dream. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, c1995. ISBN 0773513000 ISBN 0773513221

- Lotz, Jim. Prime Ministers of Canada, 1987.

- McDonald, Kenneth. His pride, our fall: recovering from the Trudeau revolution. Toronto: Key Porter Books, c1995. ISBN 155013714X

- McIlroy, Thad, ed. A Rose is a rose: a tribute to Pierre Elliott Trudeau in cartoons and quotas. Toronto: Doubleday, 1984. ISBN 038519787X ISBN 0385197888

- Nemni, Max and Nemni, Monique. Young Trudeau: Son of Quebec, Father of Canada, 1919-1944. Toronto: Douglas Gibson Books, 2006. ISBN 0771067496 (Based on private papers and diaries of Pierre Trudeau which he gave the authors in 1995)

- Peterson, Roy. Drawn & quartered: the Trudeau years. Toronto: Key Porter Books, 1984.

- Radwanski, George. Trudeau. New York: Taplinger Pub. Co., 1978. ISBN 0800878973

- Ricci, Nino. Extraordinary Canadians Pierre Elliott Trudeau (2009)

- Sawatsky, John. The Insiders: Government, Business, and the Lobbyists, 1987.

- Simpson, Jeffrey. Discipline of power: the Conservative interlude and the Liberal restoration. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1984. ISBN 0920510248

- Stewart, Walter. Shrug: Trudeau in power. Toronto: New Press, 1971. ISBN 0887700810

- Southam, Nancy. Pierre, McClelland & Stewart, September 19, 2006, 408 pages ISBN 978-0-7710-8168-2

- Simard, François-Xavier. Le vrai visage de Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Montréal: Les Intouchables, April 19, 2006 ISBN 2-89549-217-4

- Vastel, Michel. The outsider: the life of Pierre Elliott Trudeau. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, c1990. 266 pages. Translation of: Trudeau, le Québécois. ISBN 0771591004

- Walters, Eric. Voyageur, Toronto: Penguin Groups 2008

- Zink, Lubor J. Trudeaucracy. Toronto: Toronto Sun Publishing Ltd., 1972. 150 pages. ISBN 1301459780

- Archival videos of Trudeau

- Pierre Elliott Trudeau (1967–1970). Trudeau's Omnibus Bill: Challenging Canadian Taboos (.wmv) (news clips). CBC Archives. Retrieved December 5, 2006.

- Pierre Elliott Trudeau (1957–2005). Pierre Elliott Trudeau: Philosopher and Prime Minister (.wmv) (news clips). CBC Archives. Retrieved December 5, 2006.

External links

- Ill-formatted IPAc-en transclusions

- Articles with inconsistent citation formats

- Pierre Trudeau

- 1919 births

- 2000 deaths

- Alumni of the London School of Economics

- Alumni of Sciences Po

- Canadian Queen's Counsel

- Canadian legal scholars

- Canadian memoirists

- Canadian diarists

- Canadian political writers

- Canadian Roman Catholics

- Companions of the Order of Canada

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Canada

- Harvard University alumni

- Leaders of the Liberal Party of Canada

- Leaders of the Opposition (Canada)

- Members of the Canadian House of Commons from Quebec

- Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour

- Cold War leaders

- People from Montreal

- People with Parkinson's disease

- Prime Ministers of Canada

- Deaths from prostate cancer

- Academics in Quebec

- Lawyers in Quebec

- Université de Montréal alumni

- Cancer deaths in Quebec

- October Crisis

- National Historic Persons of Canada

- Canadian Newsmakers of the Year

- Trudeau family