Menopause

| Menopause | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Climacteric |

| |

| Specialty | Gynecology |

| Symptoms | No menstrual periods for a year[1] |

| Duration | ~3 years |

| Causes | Usually a natural change. Can also be caused by surgery that removes both ovaries, and some types of chemotherapy.[2][3] |

| Treatment | None, lifestyle changes[4] |

| Medication | Menopausal hormone therapy, clonidine, gabapentin, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors[4][5] |

Menopause, also known as the climacteric, is the time when menstrual periods permanently stop, marking the end of reproduction.[1][6][7] It typically occurs between the ages of 45 and 55, although the exact timing can vary.[8] Menopause is usually a natural change related to a decrease in circulating blood estrogen levels.[3] It can occur earlier in those who smoke tobacco.[2][9] Other causes include surgery that removes both ovaries, some types of chemotherapy, or anything that leads to a decrease in hormone levels.[10][2] At the physiological level, menopause happens because of a decrease in the ovaries' production of the hormones estrogen and progesterone.[1] While typically not needed, a diagnosis of menopause can be confirmed by measuring hormone levels in the blood or urine.[11] Menopause is the opposite of menarche, the time when a girl's periods start.[12]

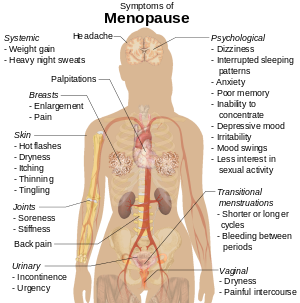

In the years before menopause, a woman's periods typically become irregular,[13][14] which means that periods may be longer or shorter in duration or be lighter or heavier in the amount of flow.[13] During this time, women often experience hot flashes; these typically last from 30 seconds to ten minutes and may be associated with shivering, night sweats, and reddening of the skin.[13] Hot flashes[13] can recur for four to five years.[6] Other symptoms may include vaginal dryness,[15] trouble sleeping, and mood changes.[13][16] The severity of symptoms varies between women.[6] Menopause before the age of 45 years is considered to be "early menopause" and when ovarian failure/surgical removal of the ovaries occurs before the age of 40 years this is termed "premature ovarian insufficiency".[17]

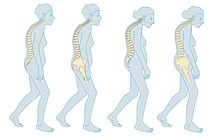

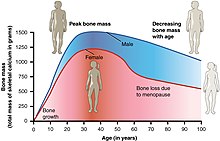

In addition to symptoms (hot flushes/flashes, night sweats, mood changes, arthralgia and vaginal dryness), the physical consequences of menopause include bone loss, increased central abdominal fat, and adverse changes in a woman's cholesterol profile and vascular function.[17] These changes predispose postmenopausal women to increased risks of osteoporosis and bone fracture, and of cardio-metabolic disease (diabetes and cardiovascular disease).[17]

Medical professionals often define menopause as having occurred when a woman has not had any menstrual bleeding for a year.[2] It may also be defined by a decrease in hormone production by the ovaries.[18] In those who have had surgery to remove their uterus but still have functioning ovaries, menopause is not considered to have yet occurred.[17] Following the removal of the uterus, symptoms of menopause typically occur earlier.[19] Iatrogenic menopause occurs when both ovaries are surgically removed along with uterus for medical reasons.

The primary indications for treatment of menopause are symptoms and prevention of bone loss.[20] Mild symptoms may be improved with treatment. With respect to hot flashes, avoiding smoking, caffeine, and alcohol is often recommended; sleeping naked in a cool room and using a fan may help. The most effective treatment for menopausal symptoms is menopausal hormone therapy (MHT).[15][20] Non-hormonal therapies for hot flashes include cognitive-behavioral therapy, clinical hypnosis, gabapentin, fezolinetant or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.[21][22] These will not improve symptoms such as joint pain or vaginal dryness which affect over 55% of women.[20] Exercise may help with sleeping problems. Many of the concerns about the use of MHT raised by older studies are no longer considered barriers to MHT in healthy women.[20] High-quality evidence for the effectiveness of alternative medicine has not been found.[6]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

During early menopause transition, the menstrual cycles remain regular but the interval between cycles begins to lengthen. Hormone levels begin to fluctuate. Ovulation may not occur with each cycle.[23]

The term menopause refers to a point in time that follows one year after the last menstruation.[23] During the menopausal transition and after menopause, women can experience a wide range of symptoms.[13] However, for women who enter the menopause transition without having regular menstrual cycles (due to prior surgery, other medical conditions or ongoing hormonal contraception) the menopause cannot be identified by bleeding patterns and is defined as the permanent loss of ovarian function.[20]

Vagina, uterus and bladder (urogenital tract)

[edit]

During the transition to menopause, menstrual patterns can show shorter cycling (by 2–7 days);[23] longer cycles remain possible.[23] There may be irregular bleeding[13] (lighter, heavier, spotting).[23] Dysfunctional uterine bleeding is often experienced by women approaching menopause due to the hormonal changes that accompany the menopause transition. Spotting or bleeding may simply be related to vaginal atrophy, a benign sore (polyp or lesion), or may be a functional endometrial response. The European Menopause and Andropause Society has released guidelines for assessment of the endometrium, which is usually the main source of spotting or bleeding.[24]

In post-menopausal women, however, any unscheduled vaginal bleeding is of concern and requires an appropriate investigation to rule out the possibility of malignant diseases.

Urogenital symptoms (that may appear during menopause and continue through postmenopause) include painful intercourse, vaginal dryness and atrophic vaginitis – thinning of the membranes of the vulva, the vagina, the cervix and the outer urinary tract, along with considerable shrinking and loss in elasticity of all of the outer and inner genital areas – urinary urgency and burning up to urinary incontinence.[23]

Other physical effects

[edit]

The most common physical symptoms of menopause are heavy night sweats, and hot flashes (also known as vasomotor symptoms).[25] Sleeping problems and insomnia are also common.[26] Other physical symptoms may be reported that are not specific to menopause but may be exacerbated by it, such as lack of energy, joint soreness, stiffness, back pain, breast enlargement, breast pain, heart palpitations, headache, dizziness, dry, itchy skin, thinning, tingling skin, rosacea, weight gain.[23][27]

Mood and memory effects

[edit]Psychological symptoms are often reported but they are not specific to menopause and can be caused by other factors.[28][29] They include anxiety, poor memory, inability to concentrate, depressive mood, irritability, mood swings, and less interest in sexual activity.[23][30][13]

Menopause-related cognitive impairment can be confused with the mild cognitive impairment that precedes dementia.[31] There is evidence of small decreases in verbal memory, on average, which may be caused by the effects of declining estrogen levels on the brain,[32] or perhaps by reduced blood flow to the brain during hot flashes.[33] However, these tend to resolve for most women during the postmenopause. Subjective reports of memory and concentration problems are associated with several factors, such as lack of sleep, and stress.[29][28]

Long-term effects

[edit]Cardiovascular health

[edit]Exposure to endogenous estrogen during reproductive years provides women with protection against cardiovascular disease, which is lost around 10 years after the onset of menopause. The menopausal transition is associated with an increase in fat mass (predominantly in visceral fat), an increase in insulin resistance, dyslipidaemia, and endothelial dysfunction.[34] Women with vasomotor symptoms during menopause seem to have an especially unfavorable cardiometabolic profile,[35] as well as women with premature onset of menopause (before 45 years of age).[36] These risks can be reduced by managing risk factors, such as tobacco smoking, hypertension, increased blood lipids and body weight.[37][38]

Bone health

[edit]The annual rates of bone mineral density loss are highest starting one year before the final menstrual period and continuing through the two years after it.[39] Thus, post menopausal women are at increased risk of osteopenia, osteoporosis and fractures.

Causes

[edit]Menopause can be induced or occur naturally. Induced menopause[40] occurs as a result of medical treatment such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, oophorectomy, or complications of tubal ligation, hysterectomy, unilateral or bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy or leuprorelin usage.[41]

Age

[edit]Menopause typically occurs at some point between 47 and 54 years of age.[8] According to various data, more than 95% of women have their last period between the ages of 44–56 (median 49–50). 2% of women under the age of 40, 5% between the ages of 40–45 and the same number between the ages of 55–58 have their last bleeding.[42] The average age of the last period in the United States is 51 years, in Russia is 50 years, in Greece is 49 years, in Turkey is 47 years, in Egypt is 47 years and in India is 46 years.[43] The menopausal transition or perimenopause leading up to menopause usually lasts 3–4 years (sometimes as long as 5–14 years).[1][14]

Undiagnosed and untreated coeliac disease is a risk factor for early menopause. Coeliac disease can present with several non-gastrointestinal symptoms, in the absence of gastrointestinal symptoms, and most cases escape timely recognition and go undiagnosed, leading to a risk of long-term complications. A strict gluten-free diet reduces the risk. Women with early diagnosis and treatment of coeliac disease present a normal duration of fertile life span.[44][45]

Women who have undergone hysterectomy with ovary conservation go through menopause on average 1.5 years earlier than the expected age.[20]

Premature ovarian insufficiency

[edit]In rare cases, a woman's ovaries stop working at a very early age, ranging anywhere from the age of puberty to age 40. This is known as premature ovarian failure and affects 1 to 2% of women by age 40.[46] also called premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) [47][48] It is diagnosed or confirmed by high blood levels of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) on at least three occasions at least four weeks apart.[49]

Premature ovarian insufficiency may be auto immune and therefore might co occur with other autoimmune disorders such as thyroid disease, [adrenal insufficiency], and diabetes mellitus. Other causes include chemotherapy, being a carrier of the fragile X syndrome gene, and radiotherapy.[48] However, in about 50–80% of cases of premature ovarian insufficiency, the cause is unknown, i.e., it is generally idiopathic.[47][49]

An early menopause can be related to cigarette smoking, higher body mass index, racial and ethnic factors, illnesses, and the removal of the uterus.[50]

Rates of premature menopause have been found to be significantly higher in fraternal and identical twins; about 5% of twins reach menopause before the age of 40.[dubious – discuss] The reasons for this are not completely understood.[51]

Surgical menopause

[edit]Menopause can be surgically induced by bilateral oophorectomy (removal of ovaries),[40] which is often, but not always, done in conjunction with removal of the fallopian tubes (salpingo-oophorectomy) and uterus (hysterectomy).[52] Cessation of menses as a result of removal of the ovaries is called "surgical menopause". Surgical treatments, such as the removal of ovaries, might cause periods to stop altogether.[53] The sudden and complete drop in hormone levels may produce extreme withdrawal symptoms such as hot flashes, etc. The symptoms of early menopause may be more severe.[53]

Removal of the uterus without removal of the ovaries does not directly cause menopause, although pelvic surgery of this type can often precipitate a somewhat earlier menopause, perhaps because of a compromised blood supply to the ovaries.[medical citation needed] The time between surgery and possible early menopause is due to the fact that ovaries are still producing hormones.[53]

Mechanism

[edit]

The menopausal transition, and postmenopause itself, is a natural change, not usually a disease state or a disorder. The main cause of this transition is the natural depletion and aging of the finite amount of oocytes (ovarian reserve). This process is sometimes accelerated by other conditions and is known to occur earlier after a wide range of gynecologic procedures such as hysterectomy (with and without ovariectomy), endometrial ablation and uterine artery embolisation. The depletion of the ovarian reserve causes an increase in circulating follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) levels because there are fewer oocytes and follicles responding to these hormones and producing estrogen.

The transition has a variable degree of effects.[54]

The stages of the menopause transition have been classified according to a woman's reported bleeding pattern, supported by changes in the pituitary follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels.[55]

In younger women, during a normal menstrual cycle the ovaries produce estradiol, testosterone and progesterone in a cyclical pattern under the control of FSH and luteinizing hormone (LH), which are both produced by the pituitary gland. During perimenopause (approaching menopause), estradiol levels and patterns of production remain relatively unchanged or may increase compared to young women, but the cycles become frequently shorter or irregular.[56] The often observed increase in estrogen is presumed to be in response to elevated FSH levels that, in turn, is hypothesized to be caused by decreased feedback by inhibin.[57] Similarly, decreased inhibin feedback after hysterectomy is hypothesized to contribute to increased ovarian stimulation and earlier menopause.[58][59]

The menopausal transition is characterized by marked, and often dramatic, variations in FSH and estradiol levels. Because of this, measurements of these hormones are not considered to be reliable guides to a woman's exact menopausal status.[57]

Menopause occurs because of the sharp decrease of estradiol and progesterone production by the ovaries. After menopause, estrogen continues to be produced mostly by aromatase in fat tissues and is produced in small amounts in many other tissues such as ovaries, bone, blood vessels, and the brain where it acts locally.[60] The substantial fall in circulating estradiol levels at menopause impacts many tissues, from brain to skin.

In contrast to the sudden fall in estradiol during menopause, the levels of total and free testosterone, as well as dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) and androstenedione appear to decline more or less steadily with age. An effect of natural menopause on circulating androgen levels has not been observed.[61] Thus specific tissue effects of natural menopause cannot be attributed to loss of androgenic hormone production.[62]

Hot flashes and other vasomotor and body symptoms accompanying the menopausal transition are associated with estrogen insufficiency and changes that occur in the brain, primarily the hypothalamus and involve complex interplay between the neurotransmitters kisspeptin, neurokinin B, and dynorphin, which are found in KNDy neurons in the infundibular nucleus.[63]

Ovarian aging

[edit]Decreased inhibin feedback after hysterectomy is hypothesized to contribute to increased ovarian stimulation and earlier menopause. Hastened ovarian aging has been observed after endometrial ablation. While it is difficult to prove that these surgeries are causative, it has been hypothesized that the endometrium may be producing endocrine factors contributing to the endocrine feedback and regulation of the ovarian stimulation. Elimination of these factors contributes to faster depletion of the ovarian reserve. Reduced blood supply to the ovaries that may occur as a consequence of hysterectomy and uterine artery embolisation has been hypothesized to contribute to this effect.[58][59]

Impaired DNA repair mechanisms may contribute to earlier depletion of the ovarian reserve during aging.[64] As women age, double-strand breaks accumulate in the DNA of their primordial follicles. Primordial follicles are immature primary oocytes surrounded by a single layer of granulosa cells. An enzyme system is present in oocytes that ordinarily accurately repairs DNA double-strand breaks. This repair system is called "homologous recombinational repair", and it is especially effective during meiosis. Meiosis is the general process by which germ cells are formed in all sexual eukaryotes; it appears to be an adaptation for efficiently removing damages in germ line DNA.[65]

Human primary oocytes are present at an intermediate stage of meiosis, termed prophase I (see Oogenesis). Expression of four key DNA repair genes that are necessary for homologous recombinational repair during meiosis (BRCA1, MRE11, Rad51, and ATM) decline with age in oocytes.[64] This age-related decline in ability to repair DNA double-strand damages can account for the accumulation of these damages, that then likely contributes to the depletion of the ovarian reserve.

Diagnosis

[edit]Ways of assessing the impact on women of some of these menopause effects, include the Greene climacteric scale questionnaire,[66] the Cervantes scale[67] and the Menopause rating scale.[68]

Perimenopause

[edit]The term "perimenopause", which literally means "around the menopause", refers to the menopause transition years before the date of the final episode of flow.[1][14][69][70] According to the North American Menopause Society, this transition can last for four to eight years.[71] The Centre for Menstrual Cycle and Ovulation Research describes it as a six- to ten-year phase ending 12 months after the last menstrual period.[72]

During perimenopause, estrogen levels average about 20–30% higher than during premenopause, often with wide fluctuations.[72] These fluctuations cause many of the physical changes during perimenopause as well as menopause, especially during the last 1–2 years of perimenopause (before menopause).[69][73] Some of these changes are hot flashes, night sweats, difficulty sleeping, mood swings, vaginal dryness or atrophy, incontinence, osteoporosis, and heart disease.[72] Perimenopause is also associated with a higher likelihood of depression (affecting from 45 percent to 68 percent of perimenopausal women), which is twice as likely to affect those with a history of depression.[74]

During this period, fertility diminishes but is not considered to reach zero until the official date of menopause. The official date is determined retroactively, once 12 months have passed after the last appearance of menstrual blood.

The menopause transition typically begins between 40 and 50 years of age (average 47.5).[75][76] The duration of perimenopause may be for up to eight years.[76] Women will often, but not always, start these transitions (perimenopause and menopause) about the same time as their mother did.[77]

Some research appears to show that melatonin supplementation in perimenopausal women can improve thyroid function and gonadotropin levels, as well as restoring fertility and menstruation and preventing depression associated with menopause.[78]

Postmenopause

[edit]The term "postmenopausal" describes women who have not experienced any menstrual flow for a minimum of 12 months, assuming that they have a uterus and are not pregnant or lactating.[52] The reason for this delay in declaring postmenopause is that periods are usually erratic during menopause. Therefore, a reasonably long stretch of time is necessary to be sure that the cycling has ceased. At this point a woman is considered infertile; however, the possibility of becoming pregnant has usually been very low (but not quite zero) for a number of years before this point is reached.[citation needed]

In women with or without a uterus, menopause or postmenopause can also be identified by a blood test showing a very high follicle-stimulating hormone level, greater than 25 IU/L in a random blood draw; it rises as ovaries become inactive.[52] FSH continues to rise, as its counterpart estradiol continues to drop for about 2 years after the last menstrual period, after which the levels of each of these hormones stabilize. The stabilization period after the begin of early postmenopause has been estimated to last 3 to 6 years, so early postmenopause lasts altogether about 5 to 8 years, during which hormone withdrawal effects such as hot flashes disappear.[52] Finally, late postmenopause has been defined as the remainder of a woman s lifespan, when reproductive hormones do not change any more.[citation needed]

A period-like flow during postmenopause, even spotting, may be a sign of endometrial cancer.

Management

[edit]Perimenopause is a natural stage of life. It is not a disease or a disorder. Therefore, it does not automatically require any kind of medical treatment. However, in those cases where the physical, mental, and emotional effects of perimenopause are strong enough that they significantly disrupt the life of the woman experiencing them, palliative medical therapy may sometimes be appropriate.

Menopausal hormone therapy

[edit]In the context of the menopause, menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) is the use of estrogen in women without a uterus and estrogen plus progestogen in women who have an intact uterus.[79]

MHT may be reasonable for the treatment of menopausal symptoms, such as hot flashes.[80] It is the most effective treatment option, especially when delivered as a skin patch.[81][82] Its use, however, appears to increase the risk of strokes and blood clots.[83] When used for menopausal symptoms the global recommendation is MHT should be prescribed for a long as there are defined treatment effects and goals for the individual woman.[20]

MHT is also effective for preventing bone loss and osteoporotic fracture,[84] but it is generally recommended only for women at significant risk for whom other therapies are unsuitable.[85]

MHT may be unsuitable for some women, including those at increased risk of cardiovascular disease, increased risk of thromboembolic disease (such as those with obesity or a history of venous thrombosis) or increased risk of some types of cancer.[85] There is some concern that this treatment increases the risk of breast cancer.[86] Women at increased risk of cardiometabolic disease and VTE may be able to use transdermal estradiol which does not appear to increase risks in low to moderate doses.[20]

Adding testosterone to hormone therapy has a positive effect on sexual function in postmenopausal women, although it may be accompanied by hair growth or acne if used in excess. Transdermal testosterone therapy in appropriate dosing is generally safe.[87]

Selective estrogen receptor modulators

[edit]SERMs are a category of drugs, either synthetically produced or derived from a botanical source, that act selectively as agonists or antagonists on the estrogen receptors throughout the body. The most commonly prescribed SERMs are raloxifene and tamoxifen. Raloxifene exhibits oestrogen agonist activity on bone and lipids, and antagonist activity on breast and the endometrium.[88] Tamoxifen is in widespread use for treatment of hormone sensitive breast cancer. Raloxifene prevents vertebral fractures in postmenopausal, osteoporotic women and reduces the risk of invasive breast cancer.[89]

Other medications

[edit]Some of the SSRIs and SNRIs appear to provide some relief from vasomotor symptoms.[22][21] The most effective SSRIs and SNRIs are paroxetine, escitalopram, citalopram, venlafaxine, and desvenlafaxine.[21] They may, however, be associated with appetite and sleeping problems, constipation and nausea.[22][90]

Gabapentin or fezolinetant can also improve the frequency and severity of vasomotor symptoms.[22][21] Side effects of using gabapentin include drowsiness and headaches.[22][90]

Therapy

[edit]Cognitive behavioural therapy and clinical hypnosis can decrease the amount women are affected by hot flashes.[21] Mindfulness is not yet proven to be effective in easing vasomotor symptoms.[91][92][21]

Lifestyle and exercise

[edit]Exercise has been thought to reduce postmenopausal symptoms through the increase of endorphin levels, which decrease as estrogen production decreases.[93] However, there is insufficient evidence to suggest that exercise helps with the symptoms of menopause.[21] Similarly, yoga has not been shown to be useful as a treatment for vasomotor symptoms.[21]

However a high BMI is a risk factor for vasomotor symptoms in particular. Weight loss may help with symptom management.[94][21]

There is no strong evidence that cooling techniques such as using specific clothing or environment control tools (for example fans) help with symptoms.[21] Paced breathing and relaxation are not effective in easing symptoms.[21]

Dietary supplements

[edit]There is no evidence of consistent benefit of taking any dietary supplements or herbal products for menopausal symptoms.[21][95][96] These widely marketed but ineffective supplements include soy isoflavones, pollen extracts, black cohosh, omega-3 among many others.[21][97][98]

Alternative medicine

[edit]There is no evidence of consistent benefit of alternative therapies for menopausal symptoms despite their popularity.[96][21]

As of 2023, there is no evidence to support the efficacy of acupuncture as a management for menopausal symptoms.[21][99][96] The Cochrane review found not enough evidence in 2016 to show a difference between Chinese herbal medicine and placebo for the vasomotor symptoms.[100]

Other efforts

[edit]- Lack of lubrication is a common problem during and after perimenopause. Vaginal moisturizers can help women with overall dryness, and lubricants can help with lubrication difficulties that may be present during intercourse. It is worth pointing out that moisturizers and lubricants are different products for different issues: some women complain that their genitalia are uncomfortably dry all the time, and they may do better with moisturizers. Those who need only lubricants do well using them only during intercourse.

- Low-dose prescription vaginal estrogen products such as estrogen creams are generally a safe way to use estrogen topically, to help vaginal thinning and dryness problems (see vaginal atrophy) while only minimally increasing the levels of estrogen in the bloodstream.

- Individual counseling or support groups can sometimes be helpful to handle sad, depressed, anxious or confused feelings women may be having as they pass through what can be for some a very challenging transition time.

- Osteoporosis can be minimized by smoking cessation, adequate vitamin D intake and regular weight-bearing exercise. The bisphosphonate drug alendronate may decrease the risk of a fracture, in women that have both bone loss and a previous fracture and less so for those with just osteoporosis.[101]

- A surgical procedure where a part of one of the ovaries is removed earlier in life and frozen and then over time thawed and returned to the body (ovarian tissue cryopreservation) has been tried. While at least 11 women have undergone the procedure and paid over £6,000, there is no evidence it is safe or effective.[102]

Society and culture

[edit]Attitudes and experiences

[edit]The menopause transition is a process, involving hormonal, menstrual, and typically vasomotor changes. However, the experience of the menopause as a whole is very much influenced by psychological and social factors, such as past experience, lifestyle, social and cultural meanings of menopause, and a woman's social and material circumstances. Menopause has been described as a biopsychosocial experience, with social and cultural factors playing a prominent role in the way menopause is experienced and perceived.[citation needed]

The paradigm within which a woman considers menopause influences the way she views it: women who understand menopause as a medical condition rate it significantly more negatively than those who view it as a life transition or a symbol of aging.[103] There is some evidence that negative attitudes and expectations, held before the menopause, predict symptom experience during the menopause,[104] and beliefs and attitudes toward menopause tend to be more positive in postmenopausal than in premenopausal women.[105] Women with more negative attitudes towards the menopause report more symptoms during this transition.[104]

Menopause is a stage of life experienced in different ways. It can be characterized by personal challenges, changes in personal roles within the family and society. Women's approaches to changes during menopause are influenced by their personal, family and sociocultural background.[106] Women from different regions and countries also have different attitudes. Postmenopausal women had more positive attitudes toward menopause compared with peri- or premenopausal women. Other influencing factors of attitudes toward menopause include age, menopausal symptoms, psychological and socioeconomical status, and profession and ethnicity.[107]

Ethnicity and geography play roles in the experience of menopause. American women of different ethnicities report significantly different types of menopausal effects. One major study found Caucasian women most likely to report what are sometimes described as psychosomatic symptoms, while African-American women were more likely to report vasomotor symptoms.[108]

There may be variations in experiences of women from different ethnic backgrounds regarding menopause and care. Immigrant women reported more vasomotor symptoms and other physical symptoms and poorer mental health than non-immigrant women and were mostly dissatisfied with the care they had received. Self-management strategies for menopausal symptoms were also influenced by culture.[109]

Two multinational studies of Asian women, found that hot flushes were not the most commonly reported symptoms, instead body and joint aches, memory problems, sleeplessness, irritability and migraines were.[110] In another study comparing experiences of menopause amongst White Australian women and women in Laos, Australian women reported higher rates of depression, as well as fears of aging, weight gain and cancer – fears not reported by Laotian women, who positioned menopause as a positive event.[111] Japanese women experience menopause effects, or konenki, in a different way from American women.[112] Japanese women report lower rates of hot flashes and night sweats; this can be attributed to a variety of factors, both biological and social. Historically, konenki was associated with wealthy middle-class housewives in Japan, i.e., it was a "luxury disease" that women from traditional, inter-generational rural households did not report. Menopause in Japan was viewed as a symptom of the inevitable process of aging, rather than a "revolutionary transition", or a "deficiency disease" in need of management.[112]

As of 2005, in Japanese culture, reporting of vasomotor symptoms has been on the increase, with research finding that of 140 Japanese participants, hot flashes were prevalent in 22.1%.[113] This was almost double that of 20 years prior.[114] Whilst the exact cause for this is unknown, possible contributing factors include dietary changes, increased medicalisation of middle-aged women and increased media attention on the subject.[114] However, reporting of vasomotor symptoms is still "significantly" lower than in North America.[115]

Additionally, while most women in the United States apparently have a negative view of menopause as a time of deterioration or decline, some studies seem to indicate that women from some Asian cultures have an understanding of menopause that focuses on a sense of liberation and celebrates the freedom from the risk of pregnancy.[116] Diverging from these conclusions, one study appeared to show that many American women "experience this time as one of liberation and self-actualization".[117]

In some women, menopause may bring about a sense of loss related to the end of fertility. In addition, this change often aligns with other stressors, such as the responsibility of looking after elderly parents or dealing with the emotional challenges of "empty nest syndrome" when children move out of the family home. This situation can be accentuated in cultures where being older is negatively perceived.

Impact on work

[edit]Midlife is typically a life stage when men and women may be dealing with demanding life events and responsibilities, such as work, health problems, and caring roles. For example, in 2018 in the UK women aged 45–54 report more work-related stress than men or women of any other age group.[118] Hot flashes are often reported to be particularly distressing at work and lead to embarrassment and worry about potential stigmatisation.[119] A June 2023 study by the Mayo Clinic estimated an annual loss of $1.8 billion in the United States due to workdays missed as a result of menopause symptoms.[120] This was one of the largest studies to date examining the impact of menopause symptoms on work outcomes. The research concluded there was a strong need to improve medical treatment for menopausal women and make the workplace environment more supportive to avoid such productivity losses.

Etymology

[edit]Menopause literally means the "end of monthly cycles" (the end of monthly periods or menstruation), from the Greek word pausis ("pause") and mēn ("month"). This is a medical coinage; the Greek word for menses is actually different. In Ancient Greek, the menses were described in the plural, ta emmēnia ("the monthlies"), and its modern descendant has been clipped to ta emmēna. The Modern Greek medical term is emmenopausis in Katharevousa or emmenopausi in Demotic Greek. The Ancient Greeks did not produce medical concepts about any symptoms associated with end of menstruation and did not use a specific word to refer to this time of a woman's life. The word menopause was invented by French doctors at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Greek etymology was reconstructed at this time and it was the Parisian student doctor Charles-Pierre-Louis de Gardanne who invented a variation of the word in 1812, which was edited to its final French form in 1821.[121]

Some of them noted that peasant women had no complaints about the end of menses, while urban middle-class women had many troubling symptoms. Doctors at this time considered the symptoms to be the result of urban lifestyles of sedentary behaviour, alcohol consumption, too much time indoors, and over-eating, with a lack of fresh fruit and vegetables.[122]

The word "menopause" was coined specifically for female humans, where the end of fertility is traditionally indicated by the permanent stopping of monthly menstruations. However, menopause exists in some other animals, many of which do not have monthly menstruation;[123] in this case, the term means a natural end to fertility that occurs before the end of the natural lifespan.

In popular culture, law and politics

[edit]In the 21st century, celebrities have spoken out about their experiences of the menopause, which has led to it becoming less of a taboo as it has boosted awareness of the debilitating symptoms. Subsequently, TV shows have been running features on the menopause to help women experiencing symptoms. In the UK Lorraine Kelly has been an advocate for getting women to speak about their experiences including sharing her own. This has led to an increase in women seeking treatment such as HRT.[124] Davina McCall also led an awareness campaign based on a documentary on Channel 4.[125]

In the UK, Carolyn Harris sponsored the Menopause (Support and Services) Bill in June 2021. It was to exempt hormone replacement therapy from National Health Service prescription charges and to make provisions about menopause support and services, including public education and communication in supporting perimenopausal and post-menopausal women, and to raise awareness of menopause and its effects. The bill was withdrawn on 29 October 2021.[126]

In the US, David McKinley, Republican from West Virginia introduced the Menopause Research Act in September 2022 for $100 million in 2023 and 2024, but it stalled.[127]

Other animals

[edit]The majority of mammal species reach menopause when they cease the production of ovarian follicles, which contain eggs (oocytes), between one-third and two-thirds of their maximum possible lifespan.[128] However, few live long enough in the wild to reach this point. Humans are joined by a limited number of other species in which females live substantially longer than their ability to reproduce. Examples of others include cetaceans: beluga whales,[129] narwhals,[129] orcas,[130] false killer whales[131] and short-finned pilot whales.[132]

Menopause has been reported in a variety of other vertebrate species, but these examples tend to be from captive individuals, and thus are not necessarily representative of what happens in natural populations in the wild. Menopause in captivity has been observed in several species of nonhuman primates,[123] including rhesus monkeys[133] and chimpanzees.[134] Some research suggests that wild chimpanzees do not experience menopause, as their fertility declines are associated with declines in overall health.[135] Menopause has been reported in elephants in captivity[136] and guppies.[137] Dogs do not experience menopause; the canine estrus cycle simply becomes irregular and infrequent. Although older female dogs are not considered good candidates for breeding, offspring have been produced by older animals, see Canine reproduction. Similar observations have been made in cats.[138]

Life histories show a varying degree of senescence; rapid senescing organisms (e.g., Pacific salmon and annual plants) do not have a post-reproductive life-stage. Gradual senescence is exhibited by all placental mammalian life histories.[original research?]

Evolution

[edit]There are various theories on the origin and process of the evolution of the menopause. These attempt to suggest evolutionary benefits to the human species stemming from the cessation of women's reproductive capability before the end of their natural lifespan. It is conjectured that in highly social groups natural selection favors females that stop reproducing and devote that post-reproductive life span to continuing to care for existing offspring, both their own and those of others to whom they are related, especially their granddaughters and grandsons.[139]

See also

[edit]- European Menopause and Andropause Society

- Menopause in the workplace

- Menopause in incarceration

- Pregnancy over age 50

- Biological clock

- Evolution of menopause

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Menopause". Office on Women's Health. 22 February 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Menopause Basics". Office on Women's Health. 22 February 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Menopause Baics". Office on Women's Health. 22 February 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ a b "What are the treatments for other symptoms of menopause?". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ Krause MS, Nakajima ST (March 2015). "Hormonal and nonhormonal treatment of vasomotor symptoms". Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 42 (1): 163–179. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2014.09.008. PMID 25681847.

- ^ a b c d Menopause: Overview. Institute for Quality & Efficiency in Health Care. 2 July 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2022 – via National Library of Medicine - Bookshelf.

- ^ Angelou K, Grigoriadis T, Diakosavvas M, Zacharakis D, Athanasiou S (8 April 2020). "The Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: An Overview of the Recent Data". Cureus. 12 (4): e7586. doi:10.7759/cureus.7586. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 7212735. PMID 32399320.

- ^ a b Takahashi TA, Johnson KM (May 2015). "Menopause". The Medical Clinics of North America. 99 (3): 521–534. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.01.006. PMID 25841598.

- ^ Warren M, Soares CN, eds. (2009). The menopausal transition: interface between gynecology and psychiatry ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Basel: Karger. p. 73. ISBN 978-3805591010.

- ^ "Menopause & Chemotherapy - Managing Side Effects - Chemocare". chemocare.com. Archived from the original on 21 November 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ "How do health care providers diagnose menopause?". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 6 May 2013. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ Wood J. "9". Dynamics of Human Reproduction: Biology, Biometry, Demography. Transaction Publishers. p. 401. ISBN 9780202365701. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Menopause Symptoms and Relief". Office on Women's Health. 22 February 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ a b c "What Is Menopause?". National Institute on Aging. 30 September 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ a b Mark JK, Samsudin S, Looi I, Yuen KH (3 May 2024). "Vaginal dryness: a review of current understanding and management strategies". Climacteric. 27 (3): 236–244. doi:10.1080/13697137.2024.2306892. ISSN 1369-7137. PMID 38318859.

- ^ Marino JM (November 2021). "Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause". Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 66 (6): 729–739. doi:10.1111/jmwh.13277. ISSN 1526-9523. PMID 34464022.

- ^ a b c d Davis SR, Lambrinoudaki I, Lumsden M, Mishra GD, Pal L, Rees M, et al. (April 2015). "Menopause". Nature Reviews. Disease Primers. 1 (1): 15004. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2015.4. PMID 27188659.

- ^ Sievert LL (2006). Menopause: a biocultural perspective ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press. p. 81. ISBN 9780813538563. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ^ International position paper on women's health and menopause : a comprehensive approach. DIANE Publishing. 2002. p. 36. ISBN 9781428905214. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Davis SR, Baber RJ (August 2022). "Treating menopause - MHT and beyond". Nature Reviews. Endocrinology. 18 (8): 490–502. doi:10.1038/s41574-022-00685-4. PMID 35624141. S2CID 249069157.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "The 2023 nonhormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society". Menopause. 30 (6): 573–590. 21 June 2023. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000002200. ISSN 1072-3714. PMID 37252752. S2CID 258969337.

- ^ a b c d e Krause MS, Nakajima ST (March 2015). "Hormonal and nonhormonal treatment of vasomotor symptoms". Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 42 (1): 163–179. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2014.09.008. PMID 25681847.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hoffman B (2012). Williams Gynecology. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 555–56. ISBN 9780071716727.

- ^ Dreisler E, Poulsen LG, Antonsen SL, Ceausu I, Depypere H, Erel CT, Lambrinoudaki I, Pérez-López FR, Simoncini T, Tremollieres F, Rees M, Ulrich LG (June 2013). "EMAS clinical guide: assessment of the endometrium in peri and postmenopausal women". Maturitas. 75 (2): 181–90. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.03.011. PMID 23619009.

- ^ Crandall CJ, Mehta JM, Manson JE (February 2023). "Management of Menopausal Symptoms: A Review". JAMA. 329 (5): 405–420. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.24140. PMID 36749328. S2CID 256628900.

- ^ Santoro N, Epperson CN, Mathews SB (September 2015). "Menopausal Symptoms and Their Management". Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 44 (3): 497–515. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2015.05.001. PMC 4890704. PMID 26316239.

- ^ "Red in the Face". NIH News in Health. 27 June 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ a b Hogervorst E, Craig J, O'Donnell E (1 May 2022). "Cognition and mental health in menopause: A review". Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. Menopause Management. 81: 69–84. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2021.10.009. ISSN 1521-6934. PMID 34969617. S2CID 244805452.

- ^ a b Kilpi F, Soares AL, Fraser A, Nelson SM, Sattar N, Fallon SJ, Tilling K, Lawlor DA (14 August 2020). "Changes in six domains of cognitive function with reproductive and chronological ageing and sex hormones: a longitudinal study in 2411 UK mid-life women". BMC Women's Health. 20 (1): 177. doi:10.1186/s12905-020-01040-3. ISSN 1472-6874. PMC 7427852. PMID 32795281.

- ^ Llaneza P, García-Portilla MP, Llaneza-Suárez D, Armott B, Pérez-López FR (February 2012). "Depressive disorders and the menopause transition". Maturitas. 71 (2): 120–30. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.11.017. PMID 22196311.

- ^ Panay N, Briggs P, Kovacs G (20 August 2015). "Memory and Mood in the Menopause". Managing the Menopause: 21st Century Solutions. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781316352717.

- ^ Birkhaeuser M, Genazzani AR (30 January 2018). Pre-Menopause, Menopause and Beyond: Volume 5: Frontiers in Gynecological Endocrinology. Springer. pp. 38–39. ISBN 9783319635408.

- ^ Papadakis MA, McPhee SJ, Rabow MW (11 September 2017). Current Medical Diagnosis and Treatment 2018, 57th Edition. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 1212. ISBN 9781259861499.

- ^ Nappi RE, Chedraui P, Lambrinoudaki I, Simoncini T (June 2022). "Menopause: a cardiometabolic transition". The Lancet. Diabetes & Endocrinology. 10 (6): 442–456. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00076-6. PMID 35525259. S2CID 248561432.

- ^ Thurston RC (April 2018). "Vasomotor symptoms: natural history, physiology, and links with cardiovascular health". Climacteric. 21 (2): 96–100. doi:10.1080/13697137.2018.1430131. PMC 5902802. PMID 29390899.

- ^ Stevenson JC, Collins P, Hamoda H, Lambrinoudaki I, Maas AH, Maclaran K, Panay N (October 2021). "Cardiometabolic health in premature ovarian insufficiency". Climacteric. 24 (5): 474–480. doi:10.1080/13697137.2021.1910232. hdl:2066/238753. PMID 34169795. S2CID 235634591.

- ^ Souza HC, Tezini GC (September 2013). "Autonomic Cardiovascular Damage during Post-menopause: the Role of Physical Training". Aging and Disease. 4 (6): 320–328. doi:10.14336/AD.2013.0400320. PMC 3843649. PMID 24307965.

- ^ ESHRE Capri Workshop Group (2011). "Perimenopausal risk factors and future health". Human Reproduction Update. 17 (5): 706–717. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr020. PMID 21565809.

- ^ Warming L, Hassager C, Christiansen C (1 February 2002). "Changes in bone mineral density with age in men and women: a longitudinal study". Osteoporosis International. 13 (2): 105–112. doi:10.1007/s001980200001. PMID 11905520. S2CID 618576.

- ^ a b "Early or premature menopause | Office on Women's Health". www.womenshealth.gov. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ "Gynaecologic Problems: Menopausal Problems". Health on the Net Foundation. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ Morabia A, Costanza MC (December 1998). "International variability in ages at menarche, first livebirth, and menopause. World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Neoplasia and Steroid Contraceptives". American Journal of Epidemiology. 148 (12): 1195–205. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009609. PMID 9867266.

- ^ Ringa V (2000). "Menopause and treatments". Quality of Life Research. 9 (6): 695–707. doi:10.1023/A:1008913605129. JSTOR 4036942. S2CID 22496307.

- ^ Tersigni C, Castellani R, de Waure C, Fattorossi A, De Spirito M, Gasbarrini A, Scambia G, Di Simone N (2014). "Celiac disease and reproductive disorders: meta-analysis of epidemiologic associations and potential pathogenic mechanisms". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (4): 582–93. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu007. hdl:10807/56796. PMID 24619876.

- ^ Lasa JS, Zubiaurre I, Soifer LO (2014). "Risk of infertility in patients with celiac disease: a meta-analysis of observational studies". Arquivos de Gastroenterologia. 51 (2): 144–50. doi:10.1590/S0004-28032014000200014. PMID 25003268.

- ^ Podfigurna-Stopa A, Czyzyk A, Grymowicz M, Smolarczyk R, Katulski K, Czajkowski K, Meczekalski B (September 2016). "Premature ovarian insufficiency: the context of long-term effects". Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 39 (9): 983–90. doi:10.1007/s40618-016-0467-z. PMC 4987394. PMID 27091671.

- ^ a b Laissue P (August 2015). "Aetiological coding sequence variants in non-syndromic premature ovarian failure: From genetic linkage analysis to next generation sequencing". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology (Review). 411: 243–57. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2015.05.005. PMID 25960166.

- ^ a b Fenton AJ (2015). "Premature ovarian insufficiency: Pathogenesis and management". Journal of Mid-Life Health (Review). 6 (4): 147–53. doi:10.4103/0976-7800.172292. PMC 4743275. PMID 26903753.

- ^ a b Kalantaridou SN, Davis SR, Nelson LM (December 1998). "Premature ovarian failure". Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 27 (4): 989–1006. doi:10.1016/s0889-8529(05)70051-7. PMID 9922918.

- ^ Bucher, et al. 1930

- ^ Gosden RG, Treloar SA, Martin NG, Cherkas LF, Spector TD, Faddy MJ, Silber SJ (February 2007). "Prevalence of premature ovarian failure in monozygotic and dizygotic twins". Human Reproduction (Oxford, England). 22 (2): 610–615. doi:10.1093/humrep/del382. ISSN 0268-1161. PMID 17065173.

- ^ a b c d Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, Lobo R, Maki P, Rebar RW, Sherman S, Sluss PM, de Villiers TJ (April 2012). "Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging". Fertility and Sterility. 97 (4): 843–51. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.01.128. PMC 3340904. PMID 22341880.

- ^ a b c "Early or premature menopause". Womenshealth.gov. 12 July 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ Cohen LS, Soares CN, Vitonis AF, Otto MW, Harlow BL (April 2006). "Risk for new onset of depression during the menopausal transition: the Harvard study of moods and cycles". Archives of General Psychiatry. 63 (4): 385–90. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.385. PMID 16585467.

- ^ Soules MR, Sherman S, Parrott E, Rebar R, Santoro N, Utian W, Woods N (December 2001). "Executive summary: Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW)". Climacteric. 4 (4): 267–72. doi:10.1080/cmt.4.4.267.272. PMID 11770182. S2CID 28673617.

- ^ Prior JC (August 1998). "Perimenopause: the complex endocrinology of the menopausal transition". Endocrine Reviews. 19 (4): 397–428. doi:10.1210/edrv.19.4.0341. PMID 9715373.

- ^ a b Burger HG (January 1994). "Diagnostic role of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) measurements during the menopausal transition—an analysis of FSH, oestradiol and inhibin". European Journal of Endocrinology. 130 (1): 38–42. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1300038. PMID 8124478.

- ^ a b Nahás E, Pontes A, Traiman P, NahásNeto J, Dalben I, De Luca L (April 2003). "Inhibin B and ovarian function after total abdominal hysterectomy in women of reproductive age". Gynecological Endocrinology. 17 (2): 125–31. doi:10.1080/713603218. PMID 12737673.

- ^ a b Petri Nahás EA, Pontes A, Nahas-Neto J, Borges VT, Dias R, Traiman P (February 2005). "Effect of total abdominal hysterectomy on ovarian blood supply in women of reproductive age". Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 24 (2): 169–74. doi:10.7863/jum.2005.24.2.169. PMID 15661947. S2CID 30259666.

- ^ Simpson ER, Davis SR (November 2001). "Minireview: aromatase and the regulation of estrogen biosynthesis—some new perspectives". Endocrinology. 142 (11): 4589–94. doi:10.1210/endo.142.11.8547. PMID 11606422.

- ^ Davison SL, Bell R, Donath S, Montalto JG, Davis SR (July 2005). "Androgen levels in adult females: changes with age, menopause, and oophorectomy". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 90 (7): 3847–53. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-0212. PMID 15827095.

- ^ Fogle RH, Stanczyk FZ, Zhang X, Paulson RJ (August 2007). "Ovarian androgen production in postmenopausal women". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 92 (8): 3040–3. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-0581. PMID 17519304.

- ^ Skorupskaite K, George JT, Anderson RA (2014). "The kisspeptin-GnRH pathway in human reproductive health and disease". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (4): 485–500. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu009. PMC 4063702. PMID 24615662.

- ^ a b Titus S, Li F, Stobezki R, Akula K, Unsal E, Jeong K, Dickler M, Robson M, Moy F, Goswami S, Oktay K (February 2013). "Impairment of BRCA1-related DNA double-strand break repair leads to ovarian aging in mice and humans". Science Translational Medicine. 5 (172): 172ra21. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3004925. PMC 5130338. PMID 23408054.

- ^ Brandl E, Mirzaghaderi G (September 2016). "The evolution of meiotic sex and its alternatives". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 283 (1838). Proc Biol Sci. doi:10.1098/rspb.2016.1221. PMC 5031655. PMID 27605505.

- ^ Greene JG (May 1998). "Constructing a standard climacteric scale". Maturitas. 29 (1): 25–31. doi:10.1016/s0378-5122(98)00025-5. PMID 9643514.

- ^ Monterrosa-Castro A, Romero-Pérez I, Marrugo-Flórez M, Fernández-Alonso AM, Chedraui P, Pérez-López FR (August 2012). "Quality of life in a large cohort of mid-aged Colombian women assessed using the Cervantes Scale". Menopause. 19 (8): 924–30. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e318247908d. PMID 22549166. S2CID 19201297.

- ^ Chedraui P, Pérez-López FR, Mendoza M, Leimberg ML, Martínez MA, Vallarino V, Hidalgo L (January 2010). "Factors related to increased daytime sleepiness during the menopausal transition as evaluated by the Epworth sleepiness scale". Maturitas. 65 (1): 75–80. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.11.003. PMID 19945237.

- ^ a b "What Is Perimenopause?". WebMD. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ "Perimenopause – Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ "Menopause 101". A primer for the perimenopausal. The North American Menopause Society. Archived from the original on 10 April 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ a b c Prior J. "Perimenopause". Centre for Menstrual Cycle and Ovulation Research (CeMCOR). Archived from the original on 25 February 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ Chichester M, Ciranni P (August–September 2011). "Approaching menopause (but not there yet!): caring for women in midlife". Nursing for Women's Health. 15 (4): 320–4. doi:10.1111/j.1751-486X.2011.01652.x. PMID 21884497.

- ^ Gilbert N (27 January 2022). "When depression sneaks up on menopause". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-012722-1. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ Hurst BS (2011). Disorders of menstruation. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781444391817.

- ^ a b McNamara M, Batur P, DeSapri KT (February 2015). "In the clinic. Perimenopause". Annals of Internal Medicine. 162 (3): ITC1–15. doi:10.7326/AITC201502030. PMID 25643316. S2CID 216041116.

- ^ Kessenich C. "Inevitable Menopause". Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Bellipanni G, DI Marzo F, Blasi F, Di Marzo A (December 2005). "Effects of melatonin in perimenopausal and menopausal women: our personal experience". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1057 (1): 393–402. Bibcode:2005NYASA1057..393B. doi:10.1196/annals.1356.030. PMID 16399909. S2CID 25213110.

- ^ The Woman's Health Program Monash University, Oestrogen and Progestin as Hormone Therapy Archived 11 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ North American Menopause Society (March 2010). "Estrogen and progestogen use in postmenopausal women: 2010 position statement of The North American Menopause Society". Menopause. 17 (2): 242–255. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e3181d0f6b9. PMID 20154637. S2CID 24806751.

- ^ North American Menopause Society (March 2012). "The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of: The North American Menopause Society". Menopause. 19 (3): 257–71. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000921. PMC 3443956. PMID 22367731.

- ^ Sarri G, Pedder H, Dias S, Guo Y, Lumsden MA (September 2017). "Vasomotor symptoms resulting from natural menopause: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of treatment effects from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline on menopause" (PDF). BJOG. 124 (10): 1514–1523. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.14619. PMID 28276200. S2CID 206909766.

- ^ Boardman HM, Hartley L, Eisinga A, Main C, Roqué i Figuls M, Bonfill Cosp X, Gabriel Sanchez R, Knight B (March 2015). "Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (3): CD002229. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002229.pub4. hdl:20.500.12105/9999. PMC 10183715. PMID 25754617.

- ^ de Villiers TJ, Stevenson JC (June 2012). "The WHI: the effect of hormone replacement therapy on fracture prevention". Climacteric. 15 (3): 263–6. doi:10.3109/13697137.2012.659975. PMID 22612613. S2CID 40340985.

- ^ a b Marjoribanks J, Farquhar C, Roberts H, Lethaby A, Lee J (January 2017). "Long-term hormone therapy for perimenopausal and postmenopausal women". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD004143. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004143.pub5. PMC 6465148. PMID 28093732.

- ^ Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL (April 2015). "Menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer mortality: clinical implications". Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety. 6 (2): 45–56. doi:10.1177/2042098614568300. PMC 4406918. PMID 25922653.

- ^ Davis SR, Baber R, Panay N, Bitzer J, Cerdas Perez S, Islam RM, et al. (October 2019). "Global Consensus Position Statement on the Use of Testosterone Therapy for Women". Climacteric. 22 (5): 429–434. doi:10.1080/13697137.2019.1637079. hdl:2158/1176450. PMID 31474158. S2CID 201713094.

- ^ Davis SR, Dinatale I, Rivera-Woll L, Davison S (May 2005). "Postmenopausal hormone therapy: from monkey glands to transdermal patches". The Journal of Endocrinology. 185 (2): 207–22. doi:10.1677/joe.1.05847. PMID 15845914.

- ^ Bevers TB (September 2007). "The STAR trial: evidence for raloxifene as a breast cancer risk reduction agent for postmenopausal women". Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 5 (8): 719–24. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2007.0073. PMID 17927929.

- ^ a b Potter B, Schrager S, Dalby J, Torell E, Hampton A (December 2018). "Menopause". Primary Care. Women's Health. 45 (4): 625–641. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2018.08.001. PMID 30401346. S2CID 239485855.

- ^ Goldstein KM, Shepherd-Banigan M, Coeytaux RR, McDuffie JR, Adam S, Befus D, et al. (April 2017). "Use of mindfulness, meditation and relaxation to treat vasomotor symptoms". Climacteric. 20 (2): 178–182. doi:10.1080/13697137.2017.1283685. PMID 28286985. S2CID 10446084.

- ^ van Driel CM, Stuursma A, Schroevers MJ, Mourits MJ, de Bock GH (February 2019). "Mindfulness, cognitive behavioural and behaviour-based therapy for natural and treatment-induced menopausal symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BJOG. 126 (3): 330–339. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.15153. PMC 6585818. PMID 29542222.

- ^ Hickey M, Szabo RA, Hunter MS (November 2017). "Non-hormonal treatments for menopausal symptoms". BMJ. 359: j5101. doi:10.1136/bmj.j5101. PMID 29170264. S2CID 46856968.

- ^ Moore TR, Franks RB, Fox C (May 2017). "Review of Efficacy of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Treatments for Menopausal Symptoms". Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 62 (3): 286–297. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12628. PMID 28561959. S2CID 4756342.

- ^ Clement YN, Onakpoya I, Hung SK, Ernst E (March 2011). "Effects of herbal and dietary supplements on cognition in menopause: a systematic review". Maturitas. 68 (3): 256–63. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.12.005. PMID 21237589.

- ^ a b c Nedrow A, Miller J, Walker M, Nygren P, Huffman LH, Nelson HD (July 2006). "Complementary and alternative therapies for the management of menopause-related symptoms: a systematic evidence review". Archives of Internal Medicine. 166 (14): 1453–65. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.14.1453. PMID 16864755.

- ^ Franco OH, Chowdhury R, Troup J, Voortman T, Kunutsor S, Kavousi M, et al. (June 2016). "Use of Plant-Based Therapies and Menopausal Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA. 315 (23): 2554–2563. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.8012. PMID 27327802.

- ^ Leach MJ, Moore V (September 2012). "Black cohosh (Cimicifuga spp.) for menopausal symptoms". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (9): CD007244. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007244.pub2. PMC 6599854. PMID 22972105.

- ^ Dodin S, Blanchet C, Marc I, Ernst E, Wu T, Vaillancourt C, Paquette J, Maunsell E (July 2013). "Acupuncture for menopausal hot flushes". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7 (7): CD007410. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007410.pub2. PMC 6544807. PMID 23897589.

- ^ Zhu X, Liew Y, Liu ZL (March 2016). "Chinese herbal medicine for menopausal symptoms". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (5): CD009023. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009023.pub2. PMC 4951187. PMID 26976671.

- ^ Wells GA, Cranney A, Peterson J, Boucher M, Shea B, Robinson V, Coyle D, Tugwell P (January 2008). "Alendronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD001155. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001155.pub2. PMID 18253985.

- ^ "Concerns over new 'menopause delay' procedure". BBC News. 28 January 2020.

- ^ Gannon L, Ekstrom B (1993). "Attitudes toward menopause: The influence of sociocultural paradigms". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 17 (3): 275–88. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1993.tb00487.x. hdl:2286/R.I.44298. S2CID 144546258.

- ^ a b Ayers B, Forshaw M, Hunter MS (January 2010). "The impact of attitudes towards the menopause on women's symptom experience: a systematic review". Maturitas. 65 (1): 28–36. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.10.016. PMID 19954900. S2CID 486661.

- ^ Brown L, Brown V, Judd F, Bryant C (2 October 2018). "It's not as bad as you think: menopausal representations are more positive in postmenopausal women". Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. 39 (4): 281–288. doi:10.1080/0167482X.2017.1368486. ISSN 0167-482X. PMID 28937311. S2CID 24085899.

- ^ Hoga L, Rodolpho J, Gonçalves B, Quirino B (September 2015). "Women's experience of menopause: a systematic review of qualitative evidence". JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports. 13 (8): 250–337. doi:10.11124/jbisrir-2015-1948. PMID 26455946. S2CID 21908463.

- ^ Dashti S, Bahri N, Fathi Najafi T, Amiridelui M, Latifnejad Roudsari R (September 2021). "Influencing factors on women's attitudes toward menopause: a systematic review". Menopause. 28 (10): 1192–1200. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001833. PMID 34520416. S2CID 237516036.

- ^ Avis N, Stellato RC, Bromberger J, Gan P, Cain V, Kagawa-Singer M (2001). "Is there a menopausal syndrome? Menopausal status and symptoms across racial/ethnic group". Social Science & Medicine. 52 (3): 345–56. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00147-7. PMID 11330770.

- ^ Stanzel KA, Hammarberg K, Fisher J (April 2018). "Experiences of menopause, self-management strategies for menopausal symptoms and perceptions of health care among immigrant women: a systematic review". Climacteric. 21 (2): 101–110. doi:10.1080/13697137.2017.1421922. PMID 29345497. S2CID 3653549.

- ^ Haines CJ, Xing SM, Park KH, Holinka CF, Ausmanas MK (November 2005). "Prevalence of menopausal symptoms in different ethnic groups of Asian women and responsiveness to therapy with three doses of conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone acetate: the Pan-Asia Menopause (PAM) study". Maturitas. 52 (3–4): 264–276. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.03.012. PMID 15921865.

- ^ Sayakhot P, Vincent A, Teede H (December 2012). "Cross-cultural study: experience, understanding of menopause, and related therapies in Australian and Laotian women". Menopause. 19 (12): 1300–1308. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e31825fd14e. PMID 22929035. S2CID 205613667.

- ^ a b Lock M (1998). "Menopause: lessons from anthropology". Psychosomatic Medicine. 60 (4): 410–9. doi:10.1097/00006842-199807000-00005. PMID 9710286. S2CID 38878080.

- ^ Melby MK (2005). "Factor analysis of climacteric symptoms in Japan". Maturitas. 52 (3–4): 205–22. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.02.002. PMID 16154301.

- ^ a b Lock M, Nguyen V (2010). "Chapter 4: Local Biologies and Human Difference". An Anthropology of Biomedicine. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 84–89.

- ^ Gold EB, Block G, Crawford S, Lachance L, FitzGerald G, Miracle H, Sherman S (June 2004). "Lifestyle and demographic factors in relation to vasomotor symptoms: baseline results from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation". American Journal of Epidemiology. 159 (12): 1189–99. doi:10.1093/aje/kwh168. PMID 15191936.

- ^ Maoz B, Dowty N, Antonovsky A, Wisjenbeck H (1970). "Female attitudes to menopause". Social Psychiatry. 5: 35–40. doi:10.1007/BF01539794. S2CID 30147685.

- ^ Stotland NL (August 2002). "Menopause: social expectations, women's realities". Archives of Women's Mental Health. 5 (1): 5–8. doi:10.1007/s007370200016. PMID 12503068. S2CID 9248759.

- ^ "Work related stress, depression or anxiety" (PDF). Health and Safety Executive (HSE). 31 October 2018.

- ^ Griffiths A, S Hunter M (2015). "Psychosocial factors and menopause: The impact of menopause on personal and working life". In C Davies S (ed.). Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer, 2014, The Health of the 51%: Women (PDF). Department of Health.

- ^ Faubion SS, Enders F, Hedges MS, Chaudhry R, Kling JM, Shufelt CL, Saadedine M, Mara K, Griffin JM, Kapoor E (1 June 2023). "Impact of Menopause Symptoms on Women in the Workplace". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 98 (6): 833–845. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.02.025. ISSN 0025-6196. PMID 37115119. S2CID 258367393.

- ^ Moore ADM |2022|The French Invention of Menopause and the Medicalisation of Women’s Ageing, A History|Oxford University Press |page 85

- ^ Moore AM (2018). "Conceptual Layers in the Invention of Menopause in Nineteenth-Century France". French History. 32 (2): 226–248. doi:10.1093/fh/cry006.

- ^ a b Walker ML, Herndon JG (September 2008). "Menopause in nonhuman primates?". Biology of Reproduction. 79 (3): 398–406. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.108.068536. PMC 2553520. PMID 18495681.

- ^ "'Breakthrough moment': how Lorraine Kelly helped shift the menopause debate". The Guardian. 29 April 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Davina McCall: Sex, Myths and the Menopause". www.channel4.com. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ House of Commons (27 October 2021). "Menopause (Support and Services) Bill, House of Commons, Session 2021-22".

- ^ McKinley, David B. (6 September 2022). "H.R.8774 - Menopause Research Act of 2022".

- ^ doi.org/k233

- ^ a b Ellis S, Franks DW, Nattrass S, Currie TE, Cant MA, Giles D, Balcomb KC, Croft DP (August 2018). "Analyses of ovarian activity reveal repeated evolution of post-reproductive lifespans in toothed whales". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 12833. Bibcode:2018NatSR...812833E. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-31047-8. PMC 6110730. PMID 30150784.

- ^ Brent LJ, Franks DW, Foster EA, Balcomb KC, Cant MA, Croft DP (March 2015). "Ecological knowledge, leadership, and the evolution of menopause in killer whales". Current Biology. 25 (6): 746–750. Bibcode:2015CBio...25..746B. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.01.037. hdl:10871/32919. PMID 25754636.

- ^ Article | Reuters - | Why did menopause evolve? New study of whales gives some clues

- ^ Marsh H, Kasuya T (1986). "Evidence for reproductive senescence in female cetaceans" (PDF). Reports of the International Whaling Commission. pp. 57–74. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ^ Walker ML (1995). "Menopause in female rhesus monkeys". American Journal of Primatology. 35 (1): 59–71. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350350106. PMC 10590078. PMID 31924061. S2CID 83848539.

- ^ Bowden DM, Williams DD (1984). "Aging". Advances in Veterinary Science and Comparative Medicine. 28: 305–341. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-039228-5.50015-2. ISBN 9780120392285. PMID 6395674.

- ^ Emery Thompson M, Jones JH, Pusey AE, Brewer-Marsden S, Goodall J, Marsden D, et al. (December 2007). "Aging and fertility patterns in wild chimpanzees provide insights into the evolution of menopause". Current Biology. 17 (24): 2150–6. Bibcode:2007CBio...17.2150E. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.033. PMC 2190291. PMID 18083515.

- ^ Sukumar R (1992). The Asian Elephant. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521437585. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016.

- ^ Reznick D, Bryant M, Holmes D (January 2006). "The evolution of senescence and post-reproductive lifespan in guppies (Poecilia reticulata)". PLOS Biology. 4 (1): e7. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040007. PMC 1318473. PMID 16363919.

- ^ "How long is a cat in heat?". Animal Planet. 15 May 2012. Archived from the original on 14 November 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ Almansa JC (16 November 2022). "The evolutionary origins of menopause explained". The Conversation. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

External links

[edit]- Menopause: MedlinePlus

- What Is Menopause?, National Institute on Aging

- Menopause & Me, The North American Menopause Society