Royal Palace of Milan

| Royal Palace of Milan | |

|---|---|

Palazzo Reale di Milano | |

Royal Palace of Milan, façade | |

| General information | |

| Status | Museum |

| Type | Palace |

| Architectural style | Neo-Classical |

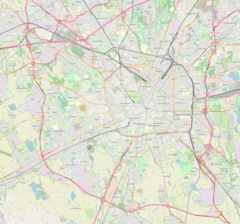

| Location | Milan, Italy |

| Address | Piazza del Duomo, 12 |

| Coordinates | 45°27′48″N 9°11′28″E / 45.4632°N 9.1911°E |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 3 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Giuseppe Piermarini |

| Website | |

| www | |

The Royal Palace of Milan (Italian: Palazzo Reale di Milano) was the seat of government in the Italian city of Milan for many centuries. Today, it serves as a cultural centre and it is home to international art exhibitions. It spans through an area of 7,000 square meters and it regularly hosts modern and contemporary art works and famous collections in cooperation with notable museums and cultural institutions from across the world.[1] More than 1,500 masterpieces are on display annually.

It was originally designed to include two courtyards but these were later dismantled to make room for the Duomo. The palazzo is located to the right of the Duomo's façade, opposite to Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II. The façade of the palazzo creates a recess in Piazza del Duomo which functions as a courtyard, known as the Piazzetta Reale (literally, a "Small Royal Square").

The famous Hall of Caryatids can be found on the main floor of the building, heavily damaged by World War II's air raids. After the war the palazzo remained abandoned for over two years and its condition further deteriorated. Many of the palazzo's neoclassical interiors were lost in this period.

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]The royal palace has ancient origins. It was first called "Palazzo del Broletto Vecchio", and it was the seat of city's government during the period of medieval communes in the Middle Ages.

The palace became a key political centre under the Torriani, Visconti and Sforza households. After the construction of the Duomo Cathedral, the palazzo was heavily renovated thanks to the efforts of Francesco I Sforza's government.

16th century

[edit]Until the early 16th century, the Dukes of Milan had their official residence in Castello Sforzesco. When the Sforza dynasty ended and the French invaded Milan, this castle became progressively more a fortress apt for warfare rather than an elegant noble residence. It was therefore under the French rule of Louis XII and of Francis I that the court was moved to Palazzo Reale.

The palazzo flourished under Governor Ferrante Gonzaga, who took permanent residence in Milan in 1546. The Gonzaga family refurbished and transformed the ducal court into a palace suitable for a governor, with expanded and newly inaugurated rooms dedicated to official functions. To pursue these expansions, governor Gonzaga demolished the old church of Sant'Andrea al Muro Rotto, annexing its land to the palazzo's complex. An interior passageway in an enclosed courtyard was created to connect the royal palace to the Church of San Gottardo, which became at this time the official church of the court.

At the end of the 16th century, Governor Antonio de Guzman y Zúñiga, Marquis of Ayamonte, recruited Pellegrino Tibaldi to conduct further renovation at the royal palace. Tibaldi, Archbishop Charles Borromeo's trusted architect, was at the time already working on the Duomo, on the Archbishop's Palace and on Cortile dei Canonici. Between 1573 and 1598 he coordinated work at the royal palace which completed overhauled the pictorial decorations of the apartments' porticoes, of the private chapel and of the Church of San Gottardo. Several major artists of the time attended to this work: Aurelio Luini, Giovanni Ambrogio Figino, Antonio Campi and naturally Pellegrino Tibaldi himself. Some stuccoes and Gothic works were created by Valerio Profondavalle, a Flemish artist-impresario who had also worked on the windows of the Duomo.

It is in this time that the Court Theater was completed, the first of a series of theaters built in Milan only to be lost to fire and replaced, until eventually La Scala was erected in the 18th century.

17th and 18th centuries

[edit]

On the night of 24 January 1695 a fire destroyed the Court Theater. Reconstruction and expansion of a new ducal theater would begin only in 1717 under the patronage of Maximilian Karl, Prince of Löwenstein-Wertheim-Rochefort, the new Austrian governor of the Duchy of Milan following the War of Spanish Succession. The new theater was designed by Francesco Galli Bibbiena and his pupils Giandomenico Barbieri and Domenico Valmagini. The theater was larger, with four tiers of boxes and a gallery in the shape of a horseshoe; on the side was a small ridottino for gambling and a shop for drinks, sweets and costumes. It was completed on 26 December 1717 and it was inaugurated with the opera Costantino by Francesco Gasparini.

In 1723 a new fire accident damaged the ceremonial halls of the palace. The Austrian governor Wirich Philipp von Daun then commissioned restorations. The wings of the Cortile d'Onore (Honor Courtyard) were updated in a livelier style, introducing whitewashed walls and baroque window frames designed by Carlo Rinaldi. The church of San Gottardo was also re-decorated in painting, stucco and gilding and upgraded to be a proper Royal-Ducal Chapel. Salone dei Festini and Salone di Audienzia (now Hall of Emperors), both on the "piano nobile" (noble floor), were also restored. The Cortile d'Onore wings housed the chancery, the magistrate and accounting offices and other administrative and financial offices. The governor and the Privy Council met in new rooms built on the north side of the garden. The governor was housed in the newly built northern and southern wings of the courtyard.

In 1745, Gian Luca Pallavicini became governor and minister plenipotentiary of Milan. He recruited the famous architect Francesco Croce of the Cathedral Workshop to completely refurbish the palace interiors (furniture, silverware, chinaware and chandeliers) at his personal expenses. Croce commissioned tapestries reproducing Raphaelite works from the Gobelins Manufactory. The halls of Festini and Audienzia were merged to create an enormous 46 by 17 meter ballroom (current Hall of the Caryatids), inclusive of side boxes to hold an orchestra. Pallavacini also requested a hall destined to host gala dinners – a new trend coming from France. When Pallavacini left in 1752, he sold his furniture and decor to the city of Milan.

Reconstruction by Piermarini

[edit]The Archduke Ferdinand of Austria-Este, son of Maria Theresa of Austria, married Maria Beatrice d'Este in Milan in 1771. For their wedding, Ascanio in Alba by Mozart was staged in the Palazzo. Mozart was initially offered a post as Maestro in the Milan court, only to be rejected at last by the Empress Maria Theresa. Maria Beatrice was heir of the Duchy of Modena and Reggio, whilst her husband was Governor of the Duchy of Milan. The Archduke Ferdinand had hoped to build a new palace, but eventually settled on remodeling the royal palace by moving out many of the administrative offices to increase the size of the royal residence.

The renovation work in 1773 was directed by Giuseppe Piermarini in collaboration with Leopold Pollack. Piermarini was tasked with the difficult job of balancing the demands of the Archduke, who was not willing to live in the royal palace unless it was grandly renovated, and the financial limitations imposed by Vienna. For the exterior he opted for an austere look, abandoning the baroque style and introducing the neoclassical in Milan. One major modification was the elimination of the wing of the courtyard adjacent to the Duomo, to create Piazzetta Reale, then larger than the square of the Cathedral. He also built the famous neoclassical façade of the palazzo that can be still admired to this day.

Fire struck again, destroying the Court Theater on February 26, 1776. It was decided at this time that the fire-prone Court Theater was to be built elsewhere: Teatro Alla Scala was erected, to become arguably the earliest public opera house in the world. A smaller court theater, now Teatro Lirico, was built closer to Palazzo Reale by demolishing a nearby school.

As per the interior work, the rooms was repurposed to meet the Archduke's requests. The most notable modification is the creation of the famous Hall of Caryatids (named after 40 caryatid sculptures by Gaetano Callani.) At the same time, the ducal chapel of San Gottardo was provided with a new altar and fully redecorated in neoclassical style. Only the bell tower was preserved without changes, being considered a model of architectural beauty by Azzone Visconti.

The Archduke ordered more Gobelins tapestries depicting stories of Jason to be placed side by side with the original ones by Pallavicini. The rooms were stuccoed by Giocondo Albertolli and frescoed by Giuliano Traballesi and Martin Knoller. Renovation works in the palace rooms continued, ending only in the 19th century with the final contributions by Andrea Appiani and Francesco Hayez.

Piermarini officially completed his work on 17 June 1778, when the Archduke officially took residence into the new Palazzo Reale.

Napoleonic era and restoration

[edit]

In 1796, Napoleon Bonaparte - still a general of the French Revolutionary Army - occupied Milan and made it capital of the newly proclaimed Cisalpine Republic, following his victory in the Battle of Lodi. The palazzo was then renamed the National Palace and became initially the seat of the Cisalpine Republic's military command and then its Directorate. When the Austro-Russians regained control of Milan in 1799, the French government quickly auctioned most of the palazzo's furnishings and allowed the rest to be looted by the general population.

After being damaged considerably, the palazzo returned to and even surpassed its former splendor in 1805, when it was eventually named "Royal Palace": Milan had become the capital of the Kingdom of Italy, ruled by Napoleon's adoptive son Eugène de Beauharnais, who was appointed viceroy and chose it to be his official residence. Milan was now the capital of a large kingdom spanning all across northern Italy and the Palazzo Reale was therefore renovated to ensure it was worthy of its title.

The damaged interiors were repaired and replaced with new and lavish furniture; Andrea Appiani worked on new frescoes in the main official rooms (Sala delle Udienze Solenni, Sala della Rotonda and Sala della Lanterna). As per the exterior, Eugène de Beauharnais invited Luigi Canonica to create an entire new block called "La Cavallerizza" (nowadays occupied by the city council offices). New stables, a large riding school and a place to give equestrian public performances, together with many offices were built in the new block in austere neo-classical style. The project was completed years later by Giacomo Tazzini, who also worked on the Via Larga façade. The complex was connected to the royal theatre (Cannobiana Theatre, at the time) through a bridge on via Restrelli.

With the fall of Napoleon in 1814, the Kingdom of Italy toppled and the huge palazzo, together with Milan, returned to Austrian hands. The Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia was formed and the royal palace remained the official seat of power of a wide realm under Austrian rule.

Recent era and loss of the Hall of Caryatids

[edit]

When Lombardy was annexed to the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1859, the royal palace became the residence of the new governor of Milan, Massimo d'Azeglio. D'Azeglio could only enjoy the palazzo for less than a year, though: following the events that led to the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861, it became one of the Savoy monarch's royal residences, even if it was not often occupied once the capital was moved to Florence. Umberto I preferred the Royal Villa of Monza to the palazzo and his son, Victor Emmanuel III, also avoided Milan and only visited the Palazzo Reale during official ceremonies. The last official royal reception held in Milan was in 1906, during the Milan International.

Palazzo Reale was to host its last official visit in 1919, when the U.S. President Woodrow Wilson was invited to Milan by Victor Emannuel III. Later that year, on October 11, the palace was sold by the House of Savoy to the Italian state, on condition that apartments would remain available for the Savoy royal family when necessary. Members of the family, among whom most notably Prince Adalberto, Duke of Bergamo, continued to live in the royal palace until the Second World War.

Big changes at the palazzo were to follow its sale. In 1850 the side nearest to the Duomo was reduced in size to allow better road traffic, thus altering radically the monumental proportions of the palace. A second disruption occurred in 1925, when the Royal Stables were demolished and then again in 1936-37 when the so-called "long sleeve" (a narrow and long wing) was shortened by at least 60 metres to build Palazzo dell'Arengario.

The whole building was heavily damaged on the night of 15 August 1943, when the city was caught in heavy bombing by the Royal Air Force. Even if the bombs only hit a small part of the roof, damage quickly extended across the whole structure because of a colossal fire that was not noted and quenched in time, testament to Milan's general state of disarray on that eventful night. All wooden fixtures and furnishings went lost and the high temperature damaged even the famous stuccoes and Appiani's paintings, ruining the Hall of Caryatids beyond repair. Its wooden beams collapsed and trusses smashed on the floor, damaging it together with the vault, the balcony and the gallery. The other halls were also damaged by water seepage, after many of the roof tiles went lost in the raid.

After a few years being left to itself, repair works at the palazzo commenced in 1947, after the end of the war. Italy's Cultural Heritage Superintendence started the refurbishment of the building and the Hall of Caryatids. A new floor and a new roof were built in a much simpler style, purposely leaving aside any ornate past decoration as a testament to the atrocities of the war. Fortunately it is still possible to admire the magnificent decorations of the Hall of Caryatids before its destruction in many paintings and photographs.

The Hall, deprived of its ancient luster, was brought back to international attention in 1953 when it was chosen by Picasso to host an exhibition. The Spanish artist's work Guernica was the main feature of the exhibition, symbolically displayed in the now much plainer Hall of Caryatids.

Starting in year 2000, the Italian government has commissioned a fuller restoration of the royal palace. The Hall of Caryatids was not redecorated to bring back its former splendor but only conservatively preserved, by removing the blackening on the walls, reinforcing the structural units and cleaning the remaining paintings. Sketches of the old ceiling were drawn on the cover of the new white ceiling, to give an impression of what the room looked like in the past.

The Museum of the Palace

[edit]At the beginning of the 21st century, more than fifty years after its destruction, Palazzo Reale found a new central role in the social and cultural life of Milan. Three phases of restoration were completed, even if the palace did not fully recover its original magnificence. The original purpose of the restorations was to create a "Palace Museum" to show the four historical seasons the Palazzo went through: the Neoclassical era, Napoleon's period, the Restoration and the Unification of Italy. The first phase of restoration undertook the complex task of refurbishing of the original furniture, to provide a stylistic representation of the life of the Ducal Court. Then the neoclassical halls were restored, to bring back the vision of Giuseppe Piermarini and the splendor of the "enlightened" era, when the city had a major role in Europe. The third phase focused on the old Apartment of Reserve, to portray the life of 19th century Austrian royalty. Unfortunately the original idea was abandoned and the Museum of the Palace was never inaugurated, despite the completion of its third phase of restoration in 2008.

Cultural centre

[edit]The Royal Palace is now a cultural centre in the heart of Milan, coordinated in conjunction with three other exhibition venues: Rotonda della Besana, Palazzo della Ragione and Palazzo dell'Arengario.

The building plays an important role within Milanese artistic life, having hosted in recent years prestigious exhibitions including works by Claude Monet, Pablo Picasso and other internationally renowned painters and sculptors. Turn-point for its prestige as exhibition hall was the 2009 show to celebrate Futurism's centenary.

Since November 4, 2013 a wing of the palace was repurposed to host the Great Museum of Milan Cathedral.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ "Palazzo Reale in Milan | Milan Museum Guide". Milan. 2013-03-09. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved 2018-06-06.

- ^ "Inauguration of the refurbishment of the Archive and of the new Grande Museo del Duomo in Milan - Archivum Fabricae". Archivio.duomomilano.it. Retrieved 2016-10-29.

Sources

[edit]- Melano, Oscar Pedro Milano di terracotta e mattoni, Mazzotta, 2002.

External links

[edit]- 1778 establishments in Italy

- Houses completed in 1778

- Museums in Milan

- Neoclassical palaces in Italy

- Palaces in Milan

- Royal residences in Italy

- Neoclassical architecture in Milan

- Gonzaga residences

- Contemporary art galleries in Italy

- Tourist attractions in Milan

- Louis XII

- Francis I of France

- Burned buildings and structures in Italy