Cybele Palace

| Cibeles Palace | |

|---|---|

Palacio de Cibeles | |

Cybele Palace, with the fountain of the same name in the foreground | |

| |

| Former names | Palacio de Comunicaciones Palacio de Telecomunicaciones |

| General information | |

| Status | Completed |

| Architectural style | Eclecticism Neo-Plateresque |

| Location | Madrid, Spain |

| Coordinates | 40°25′08″N 3°41′32″W / 40.418906°N 3.692084°W |

| Current tenants | Ayuntamiento de Madrid |

| Inaugurated | 1919 |

| Height | |

| Architectural | Spanish Property of Cultural Interest |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Antonio Palacios Joaquín Otamendi |

Cibeles Palace (Spanish: Palacio de Cibeles), formally known as Palacio de Comunicaciones (Palace of Communications) and Palacio de Telecomunicaciones (Palace of Telecommunications) until 2011, is a complex composed of two buildings with white facades and is located in one of the historical centres of Madrid, Spain. Formerly the city's main post office and telegraph and telephone headquarters, it is now occupied by City Council of Madrid, serving as the city hall, and the public cultural centre CentroCentro.

Overview

[edit]The palace was built on one of the sides of the Plaza de Cibeles in the Los Jerónimos neighbourhood (district of Retiro) and occupies about 30,000 m2 of what were the old gardens of the Buen Retiro.[1] The choice of the site generated some controversy at the time for depriving Madrid of recreational space.[2] The first stone of the building was laid in 1907. The building was officially opened on 14 March 1919 and began operating as a modern distribution centre for post, telegraphs and telephones. Following some architectural changes to the building's exterior, such as the expansion of two floors and the street and pathway of Montalbán, it began to house municipal offices of the City of Madrid in 2007, moving its departments from the Casa de la Villa (House of the City) and the Casa de Cisneros, which were both located in the Plaza de la Villa. This renovation of the building from the early twenty-first century also included a cultural area called "CentroCentro".

The whole complex, from a Spanish architecture stance, is one of the first examples of Modernismo[dubious – discuss] and most representative, to be built in the centre of Madrid,[3] with its Neoplateresque façade and Baroque Salamanca evocations.[4] The building was designed by the young Spanish architects Antonio Palacios and Joaquín Otamendi through a municipal competition to be the headquarters for the Society of Post and Telegraph of Spain.[5] Palacios and Otamendi were also the consultants for the Bilbao Bridge, Madrid Casino and the San Sebastian Bridge. The Cybele Palace was the beginning of the brilliant career in construction for both architects. The decorative motifs of the façade and interior were made by the romantic sculptor Ángel García Díaz, a regular collaborator of Antonio Palacios.[6] One of the design objectives was the construction of "a building for the public".

After their construction and due to the wear and tear of normal use, the buildings slowly started to show signs of the modifications made, which included alterations to improve the communication systems. Modifications were carried out in both buildings in the 1960s and were directed by Alejandro de la Sota. Antonio de Sala-Navarro and Reverter carried out further repairs and alterations between 1980 and 1992. The decline in the use of postal mail in the late twentieth century gradually reduced the functions of the complex, and, as a result, it began to lose its importance. In 1993 it was declared a Bien de Interés Cultural (Asset of Cultural Interest) and classified in the 'monument' category.[7] At the beginning of the 21st century it was incorporated into the municipal estate and became a cultural centre and seat of the City Council of Madrid.

History

[edit]

Madrid was growing in population and size in the seventeenth century after the decision of Philip II of Spain to transform the city onto an administrative and political centre for the nation. The Calle de Alcalá initially began at Puerta del Sol and ended at Paseo del Prado (at the height of the Plaza de Cibeles). Madrid's population growth meant that postal communication during the reign of Fernando VI of Spain was promoted through the construction of the Real Casa de Correos (Royal House of Letters), which was allocated to the Spanish architect Ventura Rodríguez. After the crowning of the new monarch Charles III of Spain, Charles III reassigned the architect Jamie Marquet to the city.[9]

The building served as the Casa de Correos (Post Office) until the construction of the new "Palacio de Comunicaciones". The location in the heart of the city resulted in road congestion and slow communication. The widening alterations to Puerta del Sol in 1856 led to the Casa de Correos finally hosting the Ministry of the Interior. The preliminary draft was approved by the minister of Public Works, Claudio Moyano, for the expansion on 19 July 1860; following the proposal project of the architect and engineer Carlos María de Castro to expand the old city limits. During Spain's restoration period, the Paseo del Prado and Recoletos continued being the preferred location for prestigious institutions and organisations, as well as mansions. Examples include, Buenavista Palace (the Army General Headquarters), which was designed by the architect Juan Pedro de Arnal in 1776 for the Dukes of Alba and the Palacio del Marqués de Linares (Palace of Linares), which is currently the Casa de América.

One of the distinguishing elements of the surroundings was the installation of the Fountain of Cybele in 1794, designed by Ventura Rodríguez. The Plaza de Cibeles was originally called Plaza de Madrid, which was renamed as the Plaza de Castelar.[10] The gardens of the Buen Retiro stretched to the Paseo del Prado.[1] The so-called gardens of San Juan seemed to be the site for the construction of the new building. The architect José Grases Riera had previously carried out studies for the remodelling of the area and had one of them published.[11] The unveilings of the gardens of the Buen Retiro in 1876 and the Hipódromo de la Castellana two years later led to the traffic moving to the junction of the Calle de Alcalá and the Paseo del Prado. This led to the disappearance of the Real Pósito and the construction of the Palacio de Linares between 1873 and 1900. The Alcañices Palace or the Duke of Sexto were demolished to make way for the building of the Bank of Spain.

On 4 April 1910 the works commenced to demolish and build the north–south road axis of Gran Vía. This new larger road axis aimed to displace the role of the east–west axis featuring the roads Mayor-Alcalá, which had previously been predicted by architect Silvestre Pérez in 1810, during the Bonapartist reign.[12]

The building: a long process

[edit]

The building took twelve years to complete. During this time, it was subjected to delays, superstitions, and various disputes. The project was approved in 1905 with construction commencing in 1907. The official opening was in 1919. After the approval of the design, the construction was interrupted and slowed down for a few years due to resistance and political struggles in the period. There were political instability and interests at that time that gave rise to the transfer of municipal sites. The Chamber of Commerce in Madrid requested cancellation of the project and called for a new competition. The construction came to a halt for two years during the time the Liberal Party was in government. The construction processes for the new post office began with the arrival of the Conservative Party. During these processes, J. Otamendi tackled two other projects in the capital. In 1908 he began the Hospital of Maudes in the neighbourhood of Cuatro Caminos and in 1910 the headquarters for the Banco Español del Río de la Plata in the neighbourhood of Alcalá.

The work officially commenced on 12 September 1907.[13] The works were awarded to the Toran and Harguindey Society. The engineer Ángel Chueca Sainz was in charge of calculating the new building's metal structures, Chueca Sainz was the father of the distinguished architect Fernando Chueca Goitia. The construction started quickly and the people gave it the humorous name 'Nuestra Señora de las Comunicaciones' (Our Lady of Communications) because of its monumental character and size. In 1916 it first opened its doors to the Public Postal Savings Bank (Caja Postal de Ahorros) despite the building not being completed until 1918.[13] The construction materials required quickly brought the el Paseo del Prado to a standstill as between one thousand five hundred and two thousand tons of iron, seven thousand cubic meters of stone and a huge quantity of bricks were required. Groups of artists and artisans were organised by the sculptor Ángel García. Among them were the ceramist Daniel Zuloaga, who suspended his involvement and Manuel Ramos Rejano, from the Sevillian ceramists, sculpted the interior decoration.

By 1916, many of the finished façade elements were visible to passers-by from the street below. The media announced that Francos Rodríguez (as Director General of Communication) and Santiago Alba (as Minister of the Interior) were to visit the construction. Interior building works were concluding between 1916 and 1918. The cost of the building was at the time twelve million pesetas, almost three times the initial amount proposed.

Inauguration and beginning

[edit]After twelve years of construction, the building was officially opened at midday on 14 March 1919, with the name 'Catedral de las Comunicaciones' (Cathedral of Communications). The royal couple, Alfonso XIII and his wife Victoria Eugenie, attended the celebration accompanied by members of the government. Their visit lasted two hours. The palace was at the time a symbol of national progress, modernity and the ideas of regenerationism that were taking root in the media and in some of the intellectuals of the age. The palace became the hub of communications in Madrid at the beginning of the twentieth century. After just one year, the palace became the international headquarters of the Universal Postal Union (UPU). One of the first responsibilities of the palace was to deal with postal traffic. Palm trees were planted in the Plaza de Cánovas during the 1920s.

In 1927 saw the construction of the rear half of the Bank of Spain (Banco de España), which is situated on Calle Alaclá, demolishing the Casas-Palacio (known as Santamarca) for its completion. The Plaza de Cibeles was the main location for various political celebrations, such as the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic on 14 April 1931, when the flag of the Second Republic was raised on the façade of the Palacio de Comunicaciones.[14] The first remodelling was undertaken, adding two further floors to the management building.

Despite the important location, the building did not suffer major damage from the bombings that devastated Madrid during the Spanish Civil War. During the Siege of Madrid, the building came under gun fire. The bullet holes can still be seen today on the building's white façade. The bullet holes were caused by the military-like actions at the end of the Civil War (at the beginning of March 1939), as a consequence of Segismundo Casado's revolt against Juan Negerín's government.[15] The constitution of the National Defence Council placed a, artillery battery in the Plaza de Cibeles. The building was involved in a battle on 8 and 9 March when communist troops succeeded in taking the Palacio de Comunicaciones within a few hours, while Casado's troops were resisting in the Naval Office (Ministerio de la Marina), the War Office and the Bank of Spain. Much later it would be confirmed as the beginning of the street Gran Vía (The Great Way).[16]

Decline in its use as a postal centre and reuse

[edit]Telegraph services continued increasing in Spain until 1987. During this period the building underwent some restorations and a whitening of its façade in 1994. Since this date, the building's use had started to decline until 2005 when it became a purely residential service; with less than five hundred users. In 1996 the architect Belén Isla Ayuso was in charge of the first restoration of the façade.[17]

The Palacio de Comunicaciones' transformation began in 2003 after the Collaboration Protocol between the City Council of Madrid and the Treasury Department to optimise the use of certain buildings in Madrid. The needs of the city hall and municipal administration had outgrown their traditional seat, the Casa de la Villa and Casa de Cisneros, both of which are located in the Plaza de la Villa.

Therefore, the city council was relocated to the much grander but underused building on Plaza de Cibeles. The first municipal bodies, including the office of the mayor, were moved in 2007; the city council held its first session in the palace in 2011.

The Casa de la Villa is still owned by the municipality and is used for receptions and other formal events.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Ariza, Carmen (1990). «Los jardines del Buen Retiro de Madrid». Lunwerg (Ayuntamiento de Madrid) II.

- ^ Pérez Rojas, Francisco Javier. «Arquitectura madrileña de la primera mitad del siglo XX : Palacios, Otamendi, Arbós, Anasagasti». Exposición celebrada en el Museo Municipal de Madrid, en marzo de 1987 (Madrid: Ayuntamiento de Madrid). ISBN 8450559227

- ^ Isla Ayuso, Belén (2000). «Palacio de Comunicaciones: intervención en una de las muestras del modernismo madrileño». Restauración & Rehabilitación: Revista Internacional del Patrimonio Histórico (44): 34-45. ISSN 1134-4571.

- ^ Pérez Rojas, Francisco Javier (1985). «Antonio Palacios y la arquitectura de su época». Villa de Madrid (Madrid: Ayuntamiento de Madrid) (38): 3-20.

- ^ Bahamonde Magro, Ángel (2000). Correos y Telégrafos, ed. El Palacio de Comunicaciones: un siglo de historia de Correos y Telégrafos (primera edición). Madrid. ISBN 84-7782-758-3.

- ^ Arévalo Cartagena, Juan Manuel (2004). «Un escultor para arquitectos: la obra de Ángel García». Goya: Revista de Arte (301-302): 289-306. ISSN 0017-2715.

- ^ REAL DECRETO 892/1993, de 4 de junio, por el que se declara bien de interés cultural con categoría de Monumento, el edificio denominado Palacio de Comunicaciones, de Madrid.

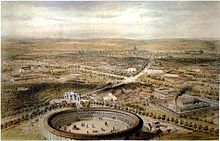

- ^ Grabado de Alfred Guesdon (Nantes, 1808-1876) realizado hacia 1854 y publicado en la revista «La Illustration, Journal Universel de París».

- ^ Virginia Tovar Martín (2008), «La Puerta del Sol y sus monumentos (siglos XVI y XVII)», Madrid, Ayuntamiento y el I.E.M. (folleto)

- ^ Acuerdo Municipal de Madrid de 14 de diciembre de 1900.

- ^ Grases Riera, José (1905). El Parque de Madrid. Los Jardines del Buen Retiro. El Salón del Prado (primera ed.). Madrid: Fortanet.

- ^ Sambricio, Carlos (1975). "Sivestre, Pérez. Un arquitecto de la Ilustración". Catálogo de Exposición. San Sebastián: Colegio de Arquitectos Vasco-Navarro.

- ^ a b Soledad, Búrdalo (2001). "Diez décadas prodigiosas: el Palacio de Comunicaciones de Madrid, símbolo de la evolución de correos en el último siglo". Revista de los Ministerios de Fomento y Medio Ambiente (494). ISSN 1136-6141.

- ^ Martínez Rus, Ana (2002). Madrid siglo XX (ed.). Proclamación de la República: La fiesta popular del 14 de julio (primera ed.). Ayuntamiento de Madrid. p. 245.

- ^ Montero Barrado, Severiano (2001). "Arqueología de la guerra civil en Madrid". Historia y Comunicación Social (6). Madrid: 97–122. ISSN 1137-0734.

- ^ Santiago Amón, (1977), Programa de TV «Trazos», recorrido por la Gran Vía

- ^ Isla Ayuso, Belén (2000). "Palacio de Comunicaciones: intervención en una de las muestras del modernismo madrileño". Restauración & Rehabilitación: Revista Internacional del Patrimonio Histórico (44): 34–45. ISSN 1134-4571.