Awlad Sidi Shaykh

| Awlad Sidi Shaykh أولاد سيدي الشيخ | |

|---|---|

| Arab tribe in Algeria | |

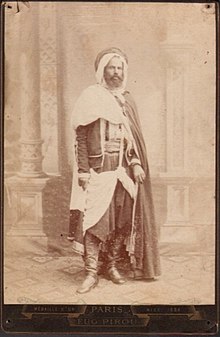

Notable of Awlad Sidi Shaykh in 1885 | |

| Ethnicity | Arab |

| Location | Western Algeria |

| Descended from | Sidi Shaykh (descendant of Abu Bakr) |

| Language | Arabic |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

The Awlad Sidi Shaykh (Arabic: أولاد سيدي الشيخ, also spelled Ouled Sidi Cheikh) was a confederation of Arab tribes in the west and south of Algeria led by the descendants of the Sufi saint Sidi Shaykh. The Awlad had religious authority, and also owned agricultural settlements and engaged in trade. During the French occupation of Algeria they alternately cooperated with and opposed the colonialists.

Origins

[edit]The Awlad Sidi Shaykh trace their ancestry to the saint Sidi Shaykh, a descendant of Muhammad's father-in-law Abu Bakr, the first caliph.[1] In the 16th century the growing population in the south-western Algerian Sahara created a need for more intense farming and for collaboration between farmers and nomads. Saint Sidi Shaykh founded a community of date farmers and nomads engaged in the caravan trade.[2] A. G. P. Martin dates this to 1651, when the walis of the Tuat and Gurara brought the Sharifian ideology to the villages of the Zenata Berbers.[3] Their headquarters was a prayer-meditation center that taught the ethics of hard work and sharing among and between the farmers and nomads.[2]

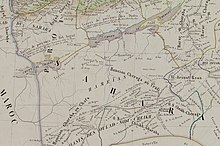

Arab tribes in the Gurara and the Sahara such as the Khenafsa became faithful to the Awlad Sidi Shaykh, the mrabtin[a] of the Saharan Atlas Mountains.[3] As the population pressure slackened in the following centuries the Awlad Sidi Shaykh gradually took control of the prayer-meditation center and grew into a mid-sized tribe. The religious ideals of cooperation were replaced by a system where the Awlad Sidi Shaykh used alms to maintain their dominance.[2] They became the dominant tribal and religious federation in the Aïn Madhi region of the central northern Algerian desert. They owned houses and storage places in the Gourara and Tuat region, and controlled zawaya religious strongholds throughout the greater Tuat. The zawaya owned large gardens worked by slaves and served as markets and travel lodges. They sent their earnings to the mother zawiya in El Abiodh Sidi Cheikh in the northwest of Algeria.[5]

Descendants of the Awlad Sidi Shaykh lived in the zawaya, where they were known as Zuwa or Ahl 'Azzi. They also owned land in the Hoggar Mountains, where they were religious scholars, teachers and traders. In the Hoggar Mountains they established agricultural settlements using slave labour, and these sometimes became staging posts on trade routes.[5] There were trading communities of the Awlad Sidi Shaykh far to the south in Timbuktu, Kidal and Agadez, and to the east in Ghadames and Ghat.[6] The confederation often came under the influence of the Sultan of Morocco.[1]

Territory

[edit]

The Awlad Sidi Shaykh have been nomadic Bedouins inhabiting the Ksour Range since the 17th century. By the late 1950s, the Awlad Sidi Shaykh nomadized between the Saharan Atlas and the pastures of the Wadi Seggueur and Wadi Gharbi, and the Ksour Range.[7]

History

[edit]Colonial era

[edit]After the French invasion of Algiers in 1830 it became clear that they might try to occupy the whole country and impose a rule much less acceptable than that of the Turkish Bey. In 1831 the Duc de Rovigo caused a scandal in Algiers when he built a military highway through two functioning cemeteries with no respect for the human remains, and converted several mosques into Catholic churches.[8] Algerians opposed to the French occupation came to accept 'Abd al-Qadir as leader of their movement.[8] Some of the Awlad Sidi Shaykh recognized 'Abd al-Qadir as sultan, as did the powerful Banu Hashim and Banu 'Amir.[9] These groups of the Oran Plateau and the Plain of Gharis accepted Muhyi al-Din, chief of the Qadiriyya Sufis, as the "Champion of Islam" against the French.[10]

In the 1840s the Awlad Sidi Shaykh assisted the Governor-General Thomas Robert Bugeaud in his struggle with the Emir 'Abd al-Qadir.[1] However, in the southern desert regions they supported 'Abd al-Qadir.[11] In the early 1850s the confederation was still divided. Some, led by Si Hamza, cooperated with the French. Others, led by Mohammed bin Abdallah, opposed them.[1]

Between 1864 and 1865 the Awlad Sidi Shaykh rose in rebellion against the French.[1] The rebellion stopped southward French expansion near Oran.[12] It was triggered by officers of the Arab Bureau (bureaux arabes) who were insensitive to the traditions of the Awlad.[13] One of the main military leaders of the revolt was Si Sliman, head of one of the main families. The French suppressed the revolt through greatly superior force.[14] Awlad Sidi Ahmad Majdub of the Amir Bedouin tribe of Morocco participated in the revolt, but was pardoned and placed in the Sebdou circle.[12] The Awlad were restive during the Kabyle Revolt (1871–72) but did not play a major role.[14] In the 1870s and 1880s local politics in Algeria were dominated by Europeans, commercial farming by French immigrants expanded, and funding for Islamic courts was cut, as was funding for schools that trained interpreters and judges. It was in this context that the Awlad Sidi Shaykh staged the last, desperate rural revolts along the frontier with Morocco.[15]

Plans to destroy the second Flatters expedition of 1880–81 were made by the Kel Ahaggar Tuaregs of the Hoggar Mountains, the Awlad Sidi Shaykh confederation and the Senussi before the expedition left Ouargla. They knew the planned route and were kept informed by the expedition guides, who helped sabotage the expedition by leading it past wells. Six hundred men of the three tribes gathered to ambush the expedition near the wells of Bir el-Garama.[16] The result was a massacre of half the expedition members, while many of the others died during a long retreat.[17]

Until 1883 the Awlad continued to occasionally mount raids against the colonialists.[14] The rebellion in the southwest led by Cheikh Bouamama (Shaykh Bu 'Amamah) from 1881 to 1883 fell apart due to disagreements among the tribes.[18] When Cheikh Bouamama retreated to Morocco in 1882 the French conquest of the south of Algeria was complete.[19] After this the Awlad Sidi Shaykh largely accepted French authority.[14] As the rebellion died down, the itinerant marabouts of the Awlad Sidi Shaykh turned to rebuilding their business, demanding donations to their shrine from the peasants, who still thought they had strong influence with God.[20] The colonial administrator Alfred Le Chatelier, a relatively enlightened secularist and republican, succeeded in convincing the Mekhedma tribe of the Sud-Oranais that they need not pay tribute.[21] There were still disturbances until 1902, and one of Awlad's leaders, Bu 'Imama, continued to resist until 1904.[22]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Naylor 2015, p. 100.

- ^ a b c Sivers 1983, pp. 113ff.

- ^ a b Bellil 1999, p. 80.

- ^ Aīssa Ouitis 1977, p. 94.

- ^ a b Scheele 2012, p. 45.

- ^ Scheele 2012, p. 46.

- ^ Despois, Jean (1959). "L'atlas saharien occidental d'Algérie : " Ksouriens " et Pasteurs". Cahiers de géographie du Québec (in French). 3 (6): 408, 414. doi:10.7202/020194ar. ISSN 0007-9766.

- ^ a b Martin 2003, p. 50.

- ^ Clancy-Smith 1994, p. 71.

- ^ Martin 2003, p. 51.

- ^ Martin 2003, p. 61.

- ^ a b Suwaed 2015, p. 23.

- ^ Naylor 2015, pp. 100–101.

- ^ a b c d Naylor 2015, p. 101.

- ^ Shillington 2013, p. 89.

- ^ Grandjean.

- ^ Ney 1891, pp. 636ff.

- ^ Krause 2017, PT175.

- ^ Sivers 2012.

- ^ Burke 2014, p. 53.

- ^ Burke 2014, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Martin 2003, pp. 39–40.

Sources

[edit]- Aīssa Ouitis (1977), Les contradictions sociales et leur expression symbolique dans le Sétifois (in French), Société nationale d'édition et de diffusion

- Bellil, Rachid (1999), Les oasis du Gourara (Sahara algérien), Peeters Publishers, ISBN 978-90-429-0721-8, retrieved 2017-09-23

- Burke, Edmund (2014-09-10), The Ethnographic State: France and the Invention of Moroccan Islam, Univ of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-27381-8, retrieved 2017-09-24

- Clancy-Smith, Julia A. (1994), Rebel and Saint, Berkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford: University of California Press, retrieved 2017-09-24

- Grandjean, Charles, "Flatters", Imago Mundi (in French), retrieved 2017-09-03

- Krause, Peter (2017-05-15), Rebel Power: Why National Movements Compete, Fight, and Win, Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-1-5017-1266-1, retrieved 2017-09-24

- Martin, B. G. (2003-02-13), Muslim Brotherhoods in Nineteenth-Century Africa, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-53451-2, retrieved 2017-09-24

- Naylor, Phillip C. (2015-05-07), Historical Dictionary of Algeria, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, ISBN 978-0-8108-7919-5, retrieved 2017-09-23

- Ney, Napoleon (1891), "The Proposed Trans-Saharian Railway", Scribner's Magazine, Charles Scribner's Sons, retrieved 2017-07-29

- Scheele, Judith (2012-04-30), Smugglers and Saints of the Sahara: Regional Connectivity in the Twentieth Century, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-02212-6, retrieved 2017-09-23

- Shillington, Kevin (2013-07-04), Encyclopedia of African History 3-Volume Set, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-135-45669-6, retrieved 2017-09-23

- Sivers, Peter von (September–December 1983), "Alms and Arms: The Combative Saintliness of the Awlad Sidi Shaykh in Algerian Sahara, Sixteenth to Nineteenth Centuries", Maghreb Review, 8 (5–6), retrieved 2017-09-23

- Sivers, Peter von (2012), "Algeria", Islamicus, retrieved 2017-09-24

- Suwaed, Muhammad (2015-10-30), Historical Dictionary of the Bedouins, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, ISBN 978-1-4422-5451-0, retrieved 2017-09-23