Jean Shepard

Jean Shepard | |

|---|---|

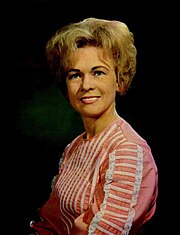

Jean Shepard, 1952. | |

| Born | Ollie Imogene Shepard November 21, 1933 Pauls Valley, Oklahoma, U.S. |

| Died | September 25, 2016 (aged 82) Gallatin, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Occupation | Singer |

| Years active | 1952–2015 |

| Works | Discography |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 3 |

| Musical career | |

| Genres |

|

| Instrument | Vocals |

| Labels |

|

Ollie Imogene "Jean" Shepard (November 21, 1933 – September 25, 2016), was an American country singer who was considered by many writers and authors to be one of the genre's first significant female artists. Her early successes during the 1950s decade were said to influence the future careers of Loretta Lynn, Dolly Parton and Tammy Wynette.

Shepard was born in Oklahoma but raised in California alongside her nine siblings. Having a musical upbringing, she formed an all-female country music band named The Melody Ranch Girls. During this period, she was heard by country artist Hank Thompson, who helped her get her first recording contract at age 18 with Capitol Records. Her second single with Ferlin Husky titled "A Dear John Letter" topped the country charts and reached the pop charts in 1953. In 1955, she had her first solo single top ten successes with "A Satisfied Mind", "I Thought of You" and "Beautiful Lies". During this period she was among the first female performers to headline shows and consistently be played on country music radio.

In 1963, Shepard's husband Hawkshaw Hawkins was killed in a plane crash. Considering ending her career, Shepard ultimately returned and in 1964 had her first top ten single in nine years with "Second Fiddle (To an Old Guitar)". She had 15 more top 40 US country singles during the decade, including the top ten recordings "If Teardrops Were Silver", "I'll Take the Dog" and "Then He Touched Me". With a dip in commercial success, Shepard became frustrated with Capitol's lack of promotion to her material and moved to United Artists Records. In 1973, she had a comeback at age 40 with the top ten song "Slippin' Away". Four more of her singles reached the US country top 20 during the 1970s.

Shepard became part of the Association of Country Entertainers (ACE) in the 1970s, which advocated for traditional country music. Her criticism of the genre's pop trends ultimately cost Shepard her recording contract from United Artists and she filed for bankruptcy during this time as well. Despite this, Shepard continued touring and became a popular attraction in European countries such as the UK and Germany. She continued sporadically recording as well, releasing her last studio album in 2000. Shepard also continued performing as a member of the Grand Ole Opry, whose cast she joined in 1955. In 2011, she was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum and continued performing through 2015.

Early life

[edit]Ollie Imogene Shepard was born in Pauls Valley, Oklahoma on November 21, 1933.[2] She was one of ten children[3] born to Hoit A. Shepard and Allie Mae Isaac Shepard. Both of her parents were sharecroppers[4] that raised cotton, sugarcane and peanuts.[5] Her father also worked additional jobs, including sewing burlap sacks at the Paul's Valley Alfalfa Mill.[6] When she was three, the family moved to Hugo, Oklahoma to be closer to her paternal grandparents. In Hugo, the Shepard family lived in a four-room house with little furniture[7] while Hoit Shepard received a government loan to sharecrop with another farmer.[5] Along with many Oklahoma farmers during the Dust Bowl, the Shepard family moved out west in search of a better life.[8] In 1943, the family settled in Visalia, California.[9]

In Visalia, Shepard skipped the third grade at Lynnwood Elementary School. In September 1947, she began the ninth grade at Visalia Union High School. In high school, she attended an accredited country music course and participated in the school's glee club.[10] She recalled being teased in her teen years for being an "Okie" who liked country music.[11] In tenth grade, Shepard and some friends formed an all-female country music band named the Melody Ranch Girls. Shepard played the upright bass in the group.[12] Her parents pawned their home's furniture to buy the instrument for Shepard.[13] Along with playing the bass, Shepard also sang, claiming to have sung "90 percent" of the lead vocals in the group.[14] She then began playing alongside the Melody Ranch Girls every weekend during her high school years.[13][15] Shepard recalled being so tired after gigs that her teachers would let her sleep during school hours.[14] Shepard then graduated from Visalia Union High School at age 17 due to her previously skipping third grade.[10]

The Melody Ranch Girls continued performing following high school, finding gigs in northern California, Oregon and Washington state.[13] The group later split after many of the band members got married.[16] Prior to their disbandment, Shepard was heard singing in the group by country performer Hank Thompson.[17][18] Thompson was impressed Shepard and told her that he would secure her a recording contract.[19] It would be several more months before she heard back from Thompson.[20]

Hank Thompson brought an acetate recording of Shepard to Ken Nelson at Capitol Records. Female country artists were not yet in vogue, therefore Nelson was hesitant to sign her to a contract.[19][13] "There's just no place in country music for women. But every band needs a girl singer," Nelson told Thompson.[19][21] Nelson then went to see Shepard perform live and was impressed. He succumb to offering her a contract, which had to be approved by a court judge because she was only 18 years old. Because the judge did not have background in the music industry, he sent Shepard to find a music business professional to look over the contract. She then brought the contract to a radio executive who gave it his blessing. The contract was then approved[22] and she officially signed with Capitol Records in 1952.[23][8]

Career

[edit]1952–1962: One of the first female country artists to find success

[edit]On September 30, 1952, Shepard made her first Capitol recordings in Hollywood, California.[24] In February 1953, Capitol released her debut single "Crying Steel Guitar Waltz".[25] The single was co-billed with steel guitar player Speedy West in belief that female country acts could not sell records alone.[24] The single was not a success.[23] Ferlin Husky then approached Nelson with a song previously recorded and played in the California region called "A Dear John Letter".[26] The song told the story of a Korean War soldier who receives a breakup letter from his female partner.[23] In May 1953,[26] "A Dear John Letter" was recorded with Shepard singing and Husky performing a spoken recitation.[8] In July 1953, it was issued as a single and reached the number one spot on the US country songs chart.[27] It also crossed over to the number four position on the US pop chart.[28] The duo then cut a follow-up release "Forgive Me, John",[9] which reached the US country top five[27] and the US pop top 30.[28] Through 1953, the Husky-Shepard duo toured the United States for a series of shows,[9][29] making an estimated $300 per gig.[29] Because the legal age was 21 to cross state lines, Husky was appointed as Shepard's guardian.[29][23]

In 1954, Capitol recorded Shepard twice more. This resulted in four singles, including "Two Whoops and a Holler" and "Please Don't Divorce Me".[30] Husky and Shepard also disbanded their duet act the same year. She briefly located to Beaumont, Texas to work with manager Neva Starnes. Throughout the southwestern US, Starnes booked Shepard on road dates with up-and-coming performer George Jones.[31] Around 1955, she joined the cast of the nationally broadcast Ozark Jubilee television show.[31][32] On one broadcast, she performed a song she recently heard called "A Satisfied Mind". Ken Nelson was then informed of the performance and brought her to California to cut it one week later. In 1955, Capitol rush-released "A Satisfied Mind" as a single.[31] Despite competing versions by Porter Wagoner and Red Foley,[31] Shepard's version reached the number four position on the US country chart[27] and ultimately became her first solo commercial success.[9] Its follow-up "I Thought of You" reached the number ten spot in 1955. In addition, both of the singles' B-sides ("Take Possession" and "Beautiful Lies") made the US country chart. Along with Kitty Wells, her back-to-back hits made Shepard one of the first solo female country artists to make the US country top ten.[27]

Shepard's success led to her induction into the cast of the Grand Ole Opry. The induction took place on her birthday in November 1955[31] and she would remain a member for 60 consecutive years.[18] With her induction, Shepard was one of only four women in the cast: Minnie Pearl, Kitty Wells and pianist Del Wood.[32] In addition, Shepard's commercial success made her one of the first solo female artists in country music to headline shows.[18] Shepard's fame prompted Capitol to issue her first studio album.[31] In May 1956, Songs of a Love Affair was released.[33] Considered one of the first country music concept albums,[34][23] Songs of a Love Affair was a collection of songs that told the point of view of woman whose spouse has been cheating on her.[35] By this point, Shepard began working steadily at the Grand Ole Opry as the cast was expected to make 26 shows per year.[36] At the Opry, Shepard developed a romantic relationship with Hawkshaw Hawkins and the two later married.[32] The pair then started touring together[36] with an ensemble that included horses and Native American performers.[37]

Capitol also continued releasing new material by Shepard.[36] She stopped recording in California after realizing she was paying out of pocket for travel. Ken Nelson then began flying to Nashville, Tennessee to produce her beginning in 1957.[38] Despite a regular output of new single releases, Shepard was unable to have commercial success for several years. This was in-part due to the influx of rock and roll and the pop-influenced Nashville Sound that overshadowed Shepard's honky tonk sound.[9][36] One exception was 1958's "I Want to Go Where No One Knows Me", which made the top 20 of the US country chart.[9][27] In December 1958, Capitol issued her second studio LP Lonesome Love, which was a concept album of love songs.[39] Shepard continued playing road shows with Hawkins and the Opry into 1960. That year, she finished sessions on her third studio LP Got You on My Mind, which Capitol issued in 1961.[36] Her fourth album Heartaches and Tears was released in 1962.[40] Critics noticed a slight incorporation of the Nashville Sound into these albums, along with Shepard's trademark honky tonk.[8][40][41]

1963–1972: Death of Hawkshaw Hawkins, comeback and leaving Capitol Records

[edit]In 1963, Hawkshaw Hawkins was killed in a plane crash, which also took the lives of Patsy Cline, Cowboy Copas and the pilot Randy Hughes.[42][23] Shepard was eight months pregnant and had a newborn child at the time of Hawkins' death.[42] After getting a settlement from the Piper Comanche company (whose airplane was involved in the crash), she debated ending her career.[43][44] Ultimately, she resumed it after being persuaded by Opry president Jack DeWitt.[42][44] Shepard then returned to the Opry stage several months after the crash.[45] She returned to the recording studio in August 1963. One of the songs recorded following the accident was "Two Little Boys".[44] The Marty Robbins-penned tune (written especially for Shepard) described how her children would carry on their father's legacy.[46] "Two Little Boys" was the B-side to her 1964 single "Second Fiddle (To an Old Guitar)".[32] The latter was considered her comeback recording[46] reaching number five on the US country songs chart, becoming her first charting single since 1959.[27] It was nominated for a Grammy award in 1965.[47]

Now under the production of Marvin Hughes, Shepard's next studio album was 1964's Lighthearted and Blue. The collection of cover tunes[44] was her first to make the US Top Country Albums chart, rising to the number 17 position.[48] Following her comeback, Shepard had a series of US charting country songs, including 15 that reached the top 40.[9][27] In 1965, both "A Tear Dropped By" and "Someone's Gotta Cry" made top 40 appearances.[44] Her 1966 single "Many Happy Hangovers to You", about a woman telling off an alcoholic husband, reached number 13 on the country chart. In 1966, both of her singles reached the country top ten: "If Teardrops Were Silver" and a duet with Ray Pillow called "I'll Take the Dog".[2] In 1967, both "Heart, We Did All That We Could" and "Your Forevers (Don't Last Very Long)" reached the top 20.[27] All seven singles were included on corresponding studio LPs that made the US country survey. Her highest-peaking LPs were Many Happy Hangovers (1966) and Heart, We Did All That We Could (1967), which both reached number six on the survey.[48] Critics from Billboard and Record World praised Shepard's vocal delivery and highlighted the emotional depth found in her albums of this era.[49][50]

In 1968, Shepard wed musician Benny Birchfield[51] and started working with new record producers.[52] This included Billy Graves (who recorded her 1968 LP Heart to Heart)[53] and Kelso Herston (who produced "Your Forevers Don't Last Very Long").[54] Shepard disliked how Herston often came into scheduled sessions drinking and wanted a change in collaborators.[55] She then chose Larry Butler, a songwriter and aspiring record producer.[56] Butler met with Herston and was given permission to work with Shepard.[57] Her first Butler-made recordings were released on the 1969 album Seven Lonely Days.[55][56] After two years of lower-charting singles, its title track reached number 18 on the US country chart in 1969.[27] It was followed by the number eight hit "Then He Touched Me", whose main character falls in love after giving up hope of finding it.[23] The Grammy-nominated song[47] was included on her 1970 album A Woman's Hand.[58] Her subsequent singles through 1971 made the US country top 30: "A Woman's Hand", "I Want You Free" and "With His Hand in Mine". The highest-climbing was the number 12 "Another Lonely Night",[27] whose main character reluctantly chooses to stay with her partner.[23] It was featured on her 1971 studio album Here & Now.[59]

In the early 1970s, Shepard became frustrated with the increasing lack of attention Capitol Records was giving to her music.[52][60] "I thought I was kinda lost in the shuffle," she later commented.[61] None of her Capitol singles following 1971 rose into the country top 40. Songs like "Safe in These Lovin' Arms of Mine" and "Virginia" only rose into the US country top 70.[27] Furthermore, her studio albums Just as Soon as I Get Over Loving You (1971)[62] and Just Like Walkin' in the Sunshine (1972)[63] failed to make the US country albums survey.[48] In 1972, Ken Nelson gave her a release from her Capitol recording contract.[52] "It was very hard for me. I cried like a baby," she remembered.[60]

1973–1979: Second comeback in her forties, ACE and traditional country music advocacy

[edit]In February 1973, Shepard signed with United Artists Records[64] and was given a large amount of money upfront to sign with the label.[55] Despite many Nashville executives believing she was past her prime,[56] Shepard was encouraged by Larry Butler (who was now running the company's country music division) to sign with the label.[56][55] Her first United Artists single was 1973's "Slippin' Away".[60] Written by Bill Anderson,[23] "Slippin' Away" rose to number four on the US Billboard country chart,[27] number three on Canada's RPM country chart[65] and made a brief appearance on the US Hot 100.[66] "Slippin' Away" became Shepard's highest-charting country single in nine years.[27] It appeared on an album of the same name that went to number 15 on the US country albums survey.[48] The disc's second single "Come on Phone" reached the US and Canadian country top 40.[27][65]

Shepard's restored commercial success at age 40 was due in-part to new production that featured upbeat tempos and hand-clapping background effects.[67] Her music's lyrical content also shifted away from honky tonk themes towards subjects of devotion and romance.[23][68] Such themes were noticed in her follow-up studio album I'll Do Anything It Takes (1974). AllMusic's Greg Adams compared Shepard's feminine themes favorably to that of similar songs by Tammy Wynette.[68] The disc reached number 21 on the US country survey.[48] Both of her singles from the album reached the US country top 20 in 1974: "I'll Do Anything It Takes (To Stay with You)" and "At the Time".[27] The latter was also penned by Bill Anderson, who also wrote her next two singles in 1975: "Poor Sweet Baby" and "The Tip of My Fingers".[69] Both songs again reached the US country songs top 20[27] and Shepard dedicated her next studio album to Anderson[70] titled Poor Sweet Baby...And Ten More Bill Anderson Songs. The disc featured the latter singles[71] and reached the top 50 of the US country chart.[48]

In 1974, Australian pop singer Olivia Newton-John won the Female Vocalist of the Year trophy on the televised Country Music Association Awards. In response, a group of country artists founded the Association of Country Entertainers (ACE), which advocated for the Country Music Association to promote the genre's traditional formats rather than appealing to crossover styles.[72] Known in the industry for promoting traditional country music,[8][9] Shepard was encouraged to join the cause[51] and was named the group's president in the 1970s.[8][2] In her 2014 autobiography, Shepard claimed that she "wasn't ever president", but instead given all of the responsibility to run it.[73] According to the Encyclopedia of Country Music, the ACE failed to have "adequate funding" and ultimately disbanded as a result.[72] According to Shepard, the ACE disbanded because she loaned money from a bank to run a local office. Members failed to keep up with payments and she took collateral on her home, but ultimately she filed for bankruptcy, which led to the ACE ending.[74]

To regain footing following her bankruptcy,[75] Shepard and Benny Birchfield bought a used Toyota and worked the touring circuit. Now her manager, Birchfield helped form her first full-time touring group named the Second Fiddles.[76] The Second Fiddles received equal billing on Shepard's 1975 live album On the Road.[77] During this period, Shepard criticized crossover country on tour and at the Grand Ole Opry, which led to country music disc jockeys to stop playing her songs.[51] Singles like "I'm a Believer (In a Whole Lot of Lovin')" and "Mercy" only reached the US country top 50, while "I'm Giving You Denver" and "Hardly a Day Goes By" only reached the top 90.[27] Her final United Artists album was Mercy, Ain't Love Good which reached the US country top 40 in 1976.[48] Shepard claimed United Artists "could not keep the wheel rolling" and she attempted to work with a new producer, George Richey.[78] Despite the change, radio backlash and media publicity continued, resulting in United Artists dropping Shepard from their roster.[79][51] She then signed with the Scorpion label,[80] who released her final-charting single "The Real Thing" in 1978.[27] She remained with Scorpion through 1979, signing a contract the same year with a new booking agency called Atlas Artist Bureau, Inc.[81]

1980–2015: Continued touring, sporadic recordings and the Grand Ole Opry

[edit]Finished with commercial country radio, Shepard continued touring and performing over the next several decades. Her music grew particularly popular in Europe, specifically in the United Kingdom where she performed frequently.[9] Among her first European engagements was the National Pure Country Music Tour in 1980 alongside Boxcar Willie.[82] Other countries Shepard recalled playing included Ireland, Germany, Austria and Sweden.[83]

In 1981, Shepard was among several Grand Ole Opry members to record a studio album under the title Stars of the Grand Ole Opry. Released by the First Generation label, Shepard's album consisted of re-recordings and some new material.[84] Billboard critics found Shepard's performance on the album to be traditional compared to her earlier recordings.[85] In 1985, she collaborated with Roy Drusky on the studio album Together at Last. Released on the Round Robin label, the project featured both duets and solo recordings by the pairing.[86] During the second half of the 1980s, Shepard advocated for Vietnam veterans[51] by fundraising.[87] Shepard often raised veteran's funds by playing shows, which sometimes were shut down by the Veteran's Administration because she did not receive permission to sponsor soldiers.[16] She continued advocating for traditional country music as well, criticizing James Brown's 1988 Grand Ole Opry performance.[88]

In 1991, the Country Harvest label released Shepard's second studio album of re-recordings titled Slippin' Away.[89] Labels began reissuing Shepard's 1950s Capitol material, beginning with 1995's Honky Tonk Heroine: Classic Capitol Recordings. Released on compact disc by the Country Music Foundation, the compilation also featured a biography and more details about the recordings in the liner notes.[90] Shepard also started appearing in filmed performances titled Country's Family Reunion during the 1990s.[21] Originally airing on the TNN network, the program eventually was released in a video format available for purchase.[91] In 2000, the Ernest Tubb Record Shop (which had its own distributing label) issued a new studio album by Shepard called The Tennessee Waltz. The album featured covers, along with new material.[92] The Raney label then released Shepard's last album called Precious Memories, a collection of gospel songs.[93]

Shepard also continued appearing as a member of the Grand Ole Opry.[23] Along with Jan Howard, Jeanne Pruett and Jeannie Seely, she was named one of the "Grand Ladies of the Grand Ole Opry" for her dedication to the venue.[94] In 2005, Shepard celebrated 50 years as a member of the Opry[95] and, at the time of her death, she was the longest-running living member of the Opry.[96] She also served as a spokesperson for the Springer Mountain Farms chicken company in the 2000s.[97] After 15 years of planning it, Shepard's autobiography was published in 2014 called Down Through the Years. The book recounted the personal and professional memories of her life up to that point.[98] On November 21, 2015, Shepard became the first woman to be a member of the Grand Ole Opry for 60 consecutive years—a feat that only one other person had achieved at the time (founding member Herman Crook of the Crook Brothers), and only one other, Bill Anderson, has reached since.[99] She retired from the stage the same night.[87][100]

Personal life

[edit]First marriage, annulment and second marriage to Hawkshaw Hawkins

[edit]

Shepard revealed in two sources that she was briefly married in 1951.[1][101] In her autobiography, she identified her husband's first name as Freddie but did not provide his last name. According to Shepard, the pair met after he was discharged from the Navy.[1] The pair met through Melody Ranch Girls member, Dixie Gardener. The pair then began going on dates and he soon proposed to her. Although she had second thoughts about the marriage, she wed Freddie shortly after her eighteenth birthday.[102] According to Shepard, Freddie disliked the idea of his wife having her own career and attempted to end her first recording contract with Capitol Records.[103] "He wanted to get me back to Tennessee where he was from and keep me barefoot and pregnant," she told liner notes author Chris Skinker.[101] Shepard also stated that Freddie had a tendency to become violent and threatened her life on multiple occasions. After one altercation, Shepard moved out of the couple's California apartment and returned to her parents' home. Shortly afterward, Shepard and her mother went before a court judge who granted her an annulment.[104]

Shepard met her second husband Hawkshaw Hawkins at the Ozark Jubilee in 1955.[23] After leaving the cast, she moved to Nashville, Tennessee where she ran into Hawkins again and the pair started a friendship.[31] The pair started a romantic relationship following Hawkins's divorce in 1958.[105] Inspired by Hank Williams's wedding, Shepard and Hawkins wed on November 26, 1960, while onstage at a concert in Wichita, Kansas.[23][106] In attendance was Ken Nelson (who gave Shepard away), Hawkins's secretary Lucille Coates and a local disc jockey broadcast the wedding over the radio.[106] Shepard gave birth to the couple's first child, Don Robin in 1961. He was named for the couple's friends, Don Gibson and Marty Robbins.[107] The couple toured together for the majority of their marriage,[108] but when they were home they often spent time hunting and fishing.[37] Hawkins and Shepard lived on a three-acre home in Goodlettsville, Tennessee that included a horse stable.[36]

On March 5, 1963, Hawkins was traveling home to Nashville by airplane alongside Patsy Cline, Cowboys Copas and pilot Randy Hughes. At the time, Shepard was eight months pregnant with the couple's second child.[44] That evening, while giving her son a bath, she began experiencing dizziness and sharp pain but ignored the symptoms and went to sleep. Shepard later theorized that her symptoms were associated with the timing of Hawkins's plane crash that day.[44][109] At 11:00 PM, she was awoken to a phone call from a friend who informed her that Hawkins's plane crashed. Shepard's doctor had to sedate her so she could rest and a highway patrol officer was stationed at her home all evening. Several friends, including Minnie Pearl, stayed by Shepard's bedside that evening.[110] At 6:00 AM, Hawkins's plane was found near Camden, Tennessee.[111] During her life, Shepard would criticize the way Patsy Cline's death in the crash overshadowed Hawkins's and others. "A lot of people think during this time that I've hated Patsy Cline, and that's not the story at all. I resented the way it was presented, like she was the only person on that airplane," she told The Tennessean in 2013.[112]

Third marriage to Archie Summers, final marriage to Benny Birchfield and death

[edit]

Following Hawkins' death, Shepard's parents stayed with her to attend to domestic duties. She gave birth to Donald Frank Hawkins II one month after her husband's plane crashed in 1963.[44] "I was so devastated for a long time. A couple of years at least – it was just rough," she remembered about grieving Hawkins.[113] Shortly after his death, Shepard sold her husband's quarter horses. After one was stolen off her property, she called the police and detective Archie Summers was sent to investigate the situation. Summers and Shepard began a romantic relationship shortly afterward[114] and the pair married in 1966.[32] Shortly after marrying, she discovered that Summers was an alcoholic but tried to keep the marriage together so her children could have a father figure. When Summers appeared at one of her concerts drunk, Shepard decided to end their marriage.[115] In 1968, the couple divorced.[32]

Shepard's final marriage was to musician Benny Birchfield and they remained together until her death in 2016[2] The pair first met at the 1966 Nashville Disc Jockey convention while Birchfield was playing in the Osborne Brothers' touring band. Birchfield then left the Osborne Brothers to play as Shepard's own road band. On the road, the pair developed a romantic relationship and the couple wed on November 21, 1968.[116] Shepard gave birth to the couple's only child together, Corey, on December 23, 1969. Birchfield also brought six more of his children into the marriage.[117] The couple eventually had 25 grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.[2] The family lived for a time in Gallatin, Tennessee in a home that cost 250,00 dollars, according to Shepard.[118] Birchfield served as Shepard's manager following their marriage.[2] During this period, Birchfield also worked as Roy Orbison's bus driver and band member.[119] Orbison often spent time at the couple's home in Nashville[120] and he was visiting them several hours before his death in 1988.[121]

In the 2010s, Shepard experienced trouble walking and had become immobile, relying on a wheelchair to move. After going to several doctors, it was discovered she had a brain deficiency and by 2013, it was treated and she resumed walking.[122] She later was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease and became increasingly debilitated by the illness.[123] In September 2016, Shepard entered hospice care[124] and died on September 25 in Gallatin, Tennessee due from complications of Parkinson's and also heart disease.[2] She was 82 years old at the time of her death.[42] A public funeral was held in Hendersonville, Tennessee on September 29.[124] Following Shepard's death, Birchfield was stabbed at their home by the boyfriend of their granddaughter, Icey Sloan-Hawkins. Birchfield killed her boyfriend with a gun and Hawkins was also later pronounced dead.[125] An investigation found that Hawkins's boyfriend had stabbed her to death and that Birchfield acted in self-defense, dismissing him from being charged with crimes.[126]

Artistry

[edit]Vocals

[edit]

Shepard's vocals have been described by music writers as having a raw and assertive sound that paired well with honky tonk music.[9][51][8] Author Kurt Wolff described her singing style as being "hardcore" and further wrote, "She had a firm voice, one that could growl as well as yelp, yodel and cry."[8] Edd Hurt of the Nashville Scene wrote, "Shepard stayed in control, but her voice gave body to songs that often explored the limits of what women could endure."[127] William Grimes of The New York Times said that she had a "female country voice with muscle and ambition".[2] Shepard also knew how to yodel, often doing so during live performances and occasionally on recordings.[128] Her yodeling was featured in the final section of her 1964 single "Second Fiddle (To an Old Guitar)"[2] Shepard later credited Jimmie Rogers records with teaching her how to yodel.[129]

Musical styles

[edit]Shepard was solely identified with the country genre throughout her career,[9] specifically with traditional country lyrically and musically.[127][2] Her recordings were often categorized into the honky tonk sub-genre,[3][8] which pointed to themes of infidelity, alcohol, romance and relationships ending.[23][130] Critics referred to her Capitol recordings for displaying honky tonk themes and found them to be the most memorable by female artists. Dan Cooper of AllMusic wrote, "She cut one great record after another, mostly on Capitol Records. Nearly all of them crackle, no matter the topic, with honky tonk angel spirit."[9] Mary A. Bufwack and Robert K. Oermann stated, "In the final roll call of the great female honky-tonk tunes are scores of Jean Shepard performances."[51]

Many of her 1950s and 1960s honky-tonk recordings portrayed women in assertive roles that predated the 1960s feminist movement.[3] William Grimes highlighted the songs "The Root of All Evil (Is a Man)" and "Many Happy Hangovers to You" for "planting the flag for independent women".[2] Kurt Wolff named "Don't Fall in Love with a Married Man" and "Sad Singin' and Slow Ridin" to be "proto-feminist and downright bold".[8] Author Peter La Chapelle wrote that she "not only sang pithy honky tonk numbers that bemoaned the behavior of the honky-tonk man, but even suggested that through collective action women could uproot the very foundations of the patriarchy".[131]

Shepard's 1950s Capitol recordings were also part of the Bakersfield Sound, a country sub-genre originating on the American west coast that had a rawer sound than its Nashville counterpart and featured Fender guitar instrumentation.[132][133] Her 1950s California recording sessions featured session musicians like Jimmy Bryant, Roy Harte, Fuzzy Owen, Buck Owens, Cliffie Stone, Lewis Talley and Speedy West.[134][135] Many of these musicians later had careers of their own and worked alongside other west country performers such as Merle Haggard.[135] Writers and historians considered 1953's "A Dear John Letter" to be the first commercially successful recording to consist entirely of Bakersfield musicians.[135][136]

When the Nashville Sound musical style ushered in pop-inspired trends, Shepard mostly kept her traditional sound,[9][8] but at times experimented with softer pop elements.[8] In reviewing 1958's Lonesome Love, AllMusic's Richie Unterberger found that the album combined "good straight-ahead honky tonk" with "satisfying injections of pop"[137] Chris Skinker of The Melody Ranch Girl box set noted that "the Nashville Sound was starting to creep into Jean's recordings" by 1961, specifically pointing to the "ethereal, echoey sound" of the guitar and the harmony vocals on specific songs.[40] As her career progressed, Shepard's song choices explored more contemporary themes of loyalty and faithfulness.[68][138] Other songs discussed sexuality such as 1974's "Poor Sweet Baby", which describes a woman and a man about to have intercourse. In 1975's "Another Neon Night", Shepard's character is involved in a one-night stand.[67][127]

Legacy, influence and achievements

[edit]Music writers, historians and journalists have noted that Jean Shepard was among country music's first commercially successful female artists.[139][72][42] With the exception of Kitty Wells and Minnie Pearl, Shepard was considered one of the female singers in the genre to reach similar success.[140] Peter Cooper of the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum wrote, "During the 1950s, few women managed to break through industry barriers to enjoy full-blown country careers, but Jean Shepard did just that."[23] Ken Burns of the PBS documentary Country Music wrote, "In the 1950s, self-supporting female country artists were rare. Women who rose to stardom on the West Coast rather than through the Grand Ole Opry were rarer still, as were women who adopted a hard-edged honky-tonk style or sang from a woman’s perspective. Jean Shepard was all that and more."[18] Mary A. Bufwack and Robert K. Oermann further explained that she was an exception due to her being a single woman: "Jean Shepard's achievement is all the more remarkable because she was the only early-1950s country music woman who made it on her own."[51]

Shepard's success in the 1950s was said to have influenced the careers of future female artists in the 1960s like Loretta Lynn, Tammy Wynette and Dolly Parton.[72][23] Other female country singers have since considered Shepard an influence, including Elizabeth Cook,[141] Reba McEntire,[142] Jeannie Seely[143] and Connie Smith.[144] Yet, Shepard was considered by writers not to get the credit she deserved. Bobbie Jean Sawyer of the Wide Open Country wrote, "Jean Shepard has never gotten her due recognition for opening doors for women in country music. But it's not too late to change that."[145] Blake Farmer of NPR reported that many people believed her future membership into the Country Hall of Fame was "overdue".[140] In regards to her own legacy, Shepard believed for many years the Country Hall of Fame ignored her early efforts. "In my case, they were about 20 years overdue. I just at some point decided they'd forgotten about me, and I forgot about them," she wrote in her autobiography.[146]

In 2010, Shepard was inducted into the Oklahoma Music Hall of Fame, her home state.[147] In 2011, Shepard was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame along with songwriter Bobby Braddock and fellow Oklahoma singer Reba McEntire.[148]

Discography

[edit]Studio albums

- Songs of a Love Affair (1956)

- Lonesome Love (1958)

- Got You on My Mind (1961)

- Heartaches and Tears (1962)

- Lighthearted and Blue (1964)

- It's a Man Every Time (1965)

- Many Happy Hangovers (1966)

- I'll Take the Dog (with Ray Pillow) (1966)

- Heart, We Did All That We Could (1967)

- Your Forevers Don't Last Very Long (1967)

- Heart to Heart (1968)

- A Real Good Woman (1968)

- I'll Fly Away (1969)[149]

- Seven Lonely Days (1969)

- Best by Request (1970)

- A Woman's Hand (1970)

- Here & Now (1971)

- Just as Soon as I Get Over Loving You (1971)

- Just Like Walkin' in the Sunshine (1972)

- Slippin' Away (1973)

- I'll Do Anything It Takes (1974)

- Poor Sweet Baby...And Ten More Bill Anderson Songs (1975)

- I'm a Believer (1975)

- Mercy, Ain't Love Good (1976)

- Stars of the Grand Ole Opry (1981)

- Together at Last (with Roy Drusky) (1985)[86]

- Slippin' Away (re-recordings) (1993)[89]

- The Tennessee Waltz (2000)[92]

- Precious Memories (2000)[93]

Books

[edit]- Down Through the Years (2014)[98]

Awards and nominations

[edit]| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | Cash Box | Best Country and Western Artist of 1953 | Nominated | [150] |

| Most Promising New Country and Western Vocalist of 1953 | Won | |||

| 1955 | Best Female Country Vocalist of 1955 | Nominated | [151] | |

| Best Country Record of 1955 – "A Satisfied Mind" | Nominated | |||

| 1956 | Best Female Vocalist | Nominated | [152] | |

| Best Country Record – "Beautiful Lies" | Nominated | |||

| 1957 | Best Female Vocalist | Nominated | [153] | |

| 1958 | Billboard | Favorite Female Artists of C&W Disc Jockeys | Nominated | [154] |

| 1959 | Cash Box | Best Country Female Vocalist of 1959 | Won | [9] |

| 1962 | Billboard | Favorite Female Artists of Country Music | Nominated | [155] |

| Cash Box | Best Female Vocalist | Nominated | [156] | |

| 1963 | Billboard | Favorite Female Country Artist | Nominated | [157] |

| 1964 | Cash Box | Best Female Vocalist | Nominated | [158] |

| 1965 | 8th Annual Grammy Awards | Best Country Vocal Performance, Female – "Second Fiddle (To an Old Guitar)" | Nominated | [47] |

| 1966 | Cashbox | Top Female Vocalist – Albums and Singles | Nominated | [159] |

| 1967 | Top Female Vocalist – Singles | Nominated | [160] | |

| Billboard | Top Female Vocalist | Nominated | [161] | |

| 1968 | Top Female Vocalist – Singles | Nominated | [162] | |

| 1970 | Nominated | [163] | ||

| 1971 | Nominated | [164] | ||

| 13th Annual Grammy Awards | Best Country Vocal Performance, Female – "Then He Touched Me" | Nominated | [47] | |

| 1973 | Billboard | Top Female Vocalist – Singles | Nominated | [165] |

| Female Artist Resurgence of the Year | Won | [166] | ||

| 1975 | Top Female Vocalist – Singles | Nominated | [167] | |

| 1976 | Nominated | [168] | ||

| 2010 | Oklahoma Music Hall of Fame | Induction | Inducted | [147] |

| 2011 | Country Music Hall of Fame | Induction | Inducted | [148][23] |

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c Shepard 2014, p. 56-58.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Grimes, William (September 27, 2016). "Jean Shepard, a Female Country Voice With Muscle and Ambition, Dies at 82". The New York Times. Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Country singer Jean Shepard dies; was Grand Ole Opry staple". The Washington Post. September 25, 2016. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 25.

- ^ a b Shepard 2014, p. 31.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 27.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 29.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Wolff, Kurt (2000). Country Music: The Rough Guide. Rough Guides Ltd. pp. 195–196. ISBN 978-1858285344.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Cooper, Dan. "Jean Shepard Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ^ a b Shepard 2014, p. 51.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 52.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 53-54.

- ^ a b c d Bufwack & Oermann 2003, p. 158.

- ^ a b Shepard 2014, p. 55.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 54-55.

- ^ a b Wolfe, Allison (November 20, 1998). "Ladies We Like: Jean Shepard". Lady Fest.org.

- ^ Thanki, Juli (November 11, 2015). "Opry to celebrate 'grand lady' Jean Shepard". The Tennessean. Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Burns, Ken. "Jean Shepard Biography". PBS. Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ^ a b c Skinker 1995, p. 7.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 63.

- ^ a b "Jean Shepard Interview". Country Stars Central. February 8, 2024. Retrieved May 18, 2024.

- ^ Skinker 1995, p. 7-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Cooper, Daniel. "Jean Shepard". Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved May 18, 2024.

- ^ a b Skinker 1995, p. 9.

- ^ Shepard, Jean; West, Speedy (February 1953). ""Crying Steel Guitar Waltz"/"Twice the Lovin' (In Half the Time)" (7" vinyl single)". Capitol Records. F-2358.

- ^ a b Skinker 1995, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Whitburn, Joel (2004). The Billboard Book Of Top 40 Country Hits: 1944-2006, Second edition. Record Research. p. 311.

- ^ a b Whitburn, Joel (1986). Joel Whitburn's Pop Memories, 1890-1954 The History of American Popular Music: Compiled from America's Popular Music Charts 1890-1954. Record Research Inc. ISBN 978-0898200836.

- ^ a b c Skinker 1995, p. 11.

- ^ Skinker 1995, p. 28.

- ^ a b c d e f g Skinker 1995, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f Bufwack & Oermann 2003, p. 159.

- ^ Shepard, Jean (May 1956). "Songs of a Love Affair (Liner Notes)". Capitol Records. T-728 (LP).

- ^ Bruce, Jennifer; Lee, Tena (2022). Southern Music Icons. The History Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-1467145411.

- ^ Kienzle, Rich (2013). Southwest Shuffle. Taylor & Francis. p. 213. ISBN 978-1136718960.

- ^ a b c d e f Skinker 1995, p. 17.

- ^ a b Shepard 2014, p. 100.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 92-93.

- ^ Shepard, Jean (December 1958). "Lonesome Love (Liner Notes)". Capitol Records. T-1126 (LP).

- ^ a b c Skinker 1995, p. 20.

- ^ "Spotlight Winners of the Week". Billboard. March 13, 1961. p. 28. Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Thanki, Juli (September 25, 2016). "Country Music Hall of Famer Jean Shepard dead at 82". The Tennessean. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 112.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Skinker 1995, p. 23.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 112-113.

- ^ a b Eder, Bruce. ""Two Little Boys": Jean Shepard: Review". AllMusic. Retrieved May 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Jean Shepard: Artist". Grammy Awards. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Whitburn, Joel (2008). Joel Whitburn Presents Hot Country Albums, 1964-2007. Record Research, Inc. ISBN 978-0898201734.

- ^ "Album Reviews: Country Spotlight". Billboard. March 11, 1967. p. 90. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ "COUNTRY LP REVIEWS" (PDF). Record World. November 9, 1968. p. 53. Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bufwack & Oermann 2003, p. 160.

- ^ a b c Shepard 2014, p. 157-158.

- ^ Shepard, Jean (February 1968). "Heart to Heart (Liner Notes)". Capitol Records. T-2871 (Mono); ST-2871 (Stereo).

- ^ Shepard, Jean (April 1967). ""Your Forevers (Don't Last Very Long)"/"Coming or Going" (7" vinyl single)". Capitol Records. 5899.

- ^ a b c d Shepard 2014, p. 158.

- ^ a b c d Kosser, Michael (2006). How Nashville Became Music City, U.S.A.: 50 Years of Music Row. Hal Leonard. p. 181. ISBN 978-0634098062.

- ^ "UA Country Artists". Billboard. Vol. 88, no. 41. October 9, 1976. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- ^ Shepard, Jean (August 1970). "A Woman's Hand (Liner Notes)". Capitol Records. ST-559.

- ^ Shepard, Jean (January 1971). "Here & Now (Liner Notes)". Capitol Records. ST-738.

- ^ a b c Skinker 1995, p. 24.

- ^ Skinker 1995, p. 157.

- ^ Shepard, Jean (August 1971). "Just as Soon as I Get Over Loving You (Liner Notes)". Capitol Records. ST-815.

- ^ Shepard, Jean (August 1972). "Just Like Walkin' in the Sunshine (Liner Notes)". Capitol Records. ST-11049.

- ^ Williams, Bill (February 17, 1973). "Nashville Scene". Billboard. Vol. 85, no. 7. Retrieved July 1, 2024.

- ^ a b "Search results for "Jean Shepard" under RPM Country Singles". RPM. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (2011). Top Pop Singles 1955–2010. Record Research, Inc. p. 758. ISBN 978-0-89820-188-8.

- ^ a b Bufwack & Oermann 2003, p. 356.

- ^ a b c Adams, Greg. "I'll Do Anything It Takes: Jean Shepard: Songs, reviews, credits". AllMusic. Retrieved July 1, 2024.

- ^ Bufwack & Oermann, p. 356.

- ^ Oermann, Robert K. (2008). Behind the Grand Ole Opry Curtain Tales of Romance and Tragedy. Center Street. ISBN 978-1599951843.

- ^ Shepard, Jean (January 1975). "Poor Sweet Baby...And Ten More Bill Anderson Songs (Liner Notes)". United Artists Records. UA-LA363-G.

- ^ a b c d Soelberg, Paul J. (2012). The Encyclopedia of Country Music. Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0199920839.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 160.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 161-163.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 163-164.

- ^ "Country Artist of the Week: Jean Shepard" (PDF). Cashbox. August 17, 1974. p. 38. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ "On the Road (Liner Notes) [as Jean Shepard and the Second Fiddles] (Liner Notes)". Jewel Records. 1974. LPS-407.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 168.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 164.

- ^ "Country: The Country Column" (PDF). Cashbox. March 25, 1978. p. 56. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ "The Country Column" (PDF). Cashbox. January 6, 1979. p. 18. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ Ball, Angela (November 8, 1980). "National Pure Country Music Tour In Lanarkshire, Scotland" (PDF). Cashbox. p. 26. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 165.

- ^ Shepard, Jean (May 1981). "Stars of the Grand Ole Opry (Liner Notes)". First Generation Records. FGLP-GOOS-09.

- ^ "Closeup" (PDF). Billboard. June 27, 1981. p. 80. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ a b Drusky, Roy; Shepard, Jean (1985). "Together at Last (Liner Notes)". Round Robin Records. DTB-666.

- ^ a b Oermann, Robert K. (September 27, 2016). "LifeNotes: Opry Matriarch Jean Shepard Passes At 82". MusicRow. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ "Thursday, March 10" (PDF). Radio & Records. February 26, 1988. p. 44. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ a b Shepard, Jean (1991). "Slippin' Away". Country Harvest Records. ER-111.

- ^ Flippo, Chet (November 4, 1995). "Promoting Cleveland's 'Only Hillbilly', Reissues from Shepard, Hillmen". Billboard. p. 55. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ Bessman, Jim (June 6, 1998). "'Reunion' Success Reveals a Vital Country Market". Billboard. p. 80. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ a b Shepard, Jean (2000). "The Tennessee Waltz (Liner Notes)". Ernest Tubb Record Shop. ETRS-1020.

- ^ a b Shepard, Jean (2000). "Precious Memories (Liner Notes)". Raney Recording Studio. 870-668-3222 (NO ID; recording studio original phone number).

- ^ "10 Opry Women Who've Blazed the Trail". Grand Ole Opry. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ "Great Ladies of the Opry/Grand Ole Opry Live Classics". Countrymusic.about.com. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ "Opry's oldest member is now Ralph Stanley". WIXY.com. March 11, 2011. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ Thompson, Gayle (June 11, 2014). "Jean Shepard Releases Autobiography". The Boot. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ a b "Jean Shepard Reflects on Her Life 'Down Through The Years'". Billboard. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ Hollabaugh, Lorie (July 6, 2023). "Bill Anderson To Be Honored As Longest-Serving Grand Ole Opry Member". MusicRow.com. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ "Grand Ole Opry Icon Jean Shepard Dead at 82". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 29, 2018. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ a b Skinker 1995, p. 6.

- ^ Shepard, p. 56.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 57.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 57-58.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 97.

- ^ a b Shepard 2014, p. 99.

- ^ Skinker, p. 22-23.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 98.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 108.

- ^ Nassour, Ellis (1993). Honky Tonk Angel: The Intimate Story of Patsy Cline. St. Martin's Press. p. 229. ISBN 0-312-08870-1.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 109.

- ^ Cooper, Peter (March 4, 2019). "Patsy Cline: Country music remembers its darkest day". The Tennessean. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 110.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 118-119.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 120.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 137-138.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 142.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 162.

- ^ Garrison, Joey (December 18, 2016). "UPDATE: 2 killed, husband of late country music star Jean Shepard injured in Hendersonville attack". The Tennessean. Retrieved July 9, 2024.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 144.

- ^ Folkart, Burt A. (December 8, 1988). "From the Archives: Rock 'n' Roll's Roy Orbison Dies". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 9, 2024.

- ^ "Jean Shepard: Eddie Stubbs Celebrity Salute: WSM Radio". YouTube. November 4, 2014. Event occurs at 4:12. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ Mirkin, Gabe (December 18, 2016). "Jean Shepard broke down barriers in country music, later battled Parkinson's Disease". Villages-News. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ a b Reuter, Annie (September 28, 2016). "Jean Shepard's Funeral to Be Open to the Public". Taste of Country. Retrieved July 9, 2024.

- ^ "Report: Trying to protect granddaughter, country star's widower killed man, family says". CBS News. December 20, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2024.

- ^ Cross, Josh (December 20, 2016). "No charges against Jean Shepard's husband in shooting". The Tennessean. Retrieved July 9, 2024.

- ^ a b c Hurt, Edd. "Remembering Jean Shepard". Nashville Scene. Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- ^ Bufwack & Oermann 2003, p. 158-159.

- ^ Skinker 1995, p. 5.

- ^ Bufwack & Oermann 2003, p. 143.

- ^ La Chapelle, Peter (2004). A Boy Named Sue Gender and Country Music. University of Mississippi. p. 38. ISBN 978-1604739565.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie; Hicks, Samb (1999). Music USA: The Rough Guide. Rough Guides Ltd. p. 406. ISBN 978-1858284217.

- ^ Meares, Hadley (September 13, 2019). "The Streets of Bakersfield: Maverick Music in California's Nashville West". PBS. Retrieved July 12, 2024.

- ^ Skinker 1995, p. 9-13.

- ^ a b c "Women of West Coast Country: Panel Discussion". Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. Event occurs at 1:02:37. Retrieved July 12, 2024.

- ^ "Jean Shepard: She gave Bakersfield Sound its first hit". Bakersfield.com. December 25, 2016. Retrieved July 12, 2024.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "Lonesome Love/This Is Jean Shepard: Jean Shepard: Songs, reviews, credits". AllMusic. Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- ^ Adams, Greg. "Seven Lonely Days: Jean Shepard: Songs, reviews credits". AllMusic. Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- ^ Abjorensen, Norman (2017). Historical Dictionary of Popular Music. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 116. ISBN 978-1538102152.

- ^ a b Farmer, Blake (September 27, 2016). "'There Wasn't None Of Us': Jean Shepard, Country Music Trailblazer, Dies At 82". NPR. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ Conway, Tom (March 12, 2017). "Elizabeth Cook fine with being country music outsider". South Bend Tribune. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ Richards, Kevin (June 24, 2011). "Jean Shepard Discusses Hall of Fame Induction and Being a Pioneer for Women in Country Music". Taste of Country. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ Homer, Sheree (2019). Under the Influence of Classic Country. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company. p. 108. ISBN 978-1476637075.

- ^ Cooper, Daniel. "Connie Smith". Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ Sawyer, Bobbie Jean (December 30, 2022). "Female Country Singers: The Top 45 Singers of All Time". Wide Open Country. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ Shepard 2014, p. 203.

- ^ a b Lang, George (November 5, 2010). "Oklahoma Music Hall of Fame inducts Jean Shepard, Les Gilliam, Sam Harris and Jamie Oldaker". The Oklahoman. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ a b "Reba McEntire among Country Hall of Fame inductees". Reuters. March 2011. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ Shepard, Jean (February 1969). "I'll Fly Away (Liner Notes)". Capitol Records. ST-171.

- ^ "For Ops to Vote" (PDF). Cash Box. November 28, 1953. p. 5. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "Left to Cast 'Cash Box' Poll" (PDF). Cash Box. November 19, 1955. p. 5. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "For 1956 Poll!" (PDF). Cash Box. December 8, 1956. p. 5. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "For 1957 Poll!" (PDF). Cash Box. December 7, 1957. p. 9. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "The Billboard 11th Annual Disc Jockey Poll" (PDF). Billboard. November 17, 1958. p. 20. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "15th Annual Country Music Disc Jockeys Poll" (PDF). Billboard. November 10, 1962. p. 25. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "Top Country Records & Artists of 1962" (PDF). Cash Box. December 29, 1962. p. 128. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "Country Music Awards" (PDF). Billboard. December 28, 1963. p. 67. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "Best Country Artists of 1964" (PDF). Cash Box. December 26, 1964. p. 66. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "Best Country Records of 1966" (PDF). Cashbox. December 23, 1967. p. 110. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "Best Country Records of 1967" (PDF). Cashbox. December 24, 1966. p. 124. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "Top Country Artists: Female Vocalist" (PDF). Billboard. October 28, 1967. p. 12. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "Top Country Singles Artists: Female Vocalist" (PDF). Billboard. October 19, 1968. p. 16. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "Top Artists by Category" (PDF). Billboard. October 17, 1970. p. CM-12. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ^ "Top Female Vocalist" (PDF). Billboard. October 16, 1971. p. 18. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "World of Country Music" (PDF). Billboard. October 20, 1973. p. 18. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "Billboard Country Awards" (PDF). Billboard. February 16, 1974. p. 36. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "1975 Country Music Chart Winners" (PDF). Billboard. October 18, 1975. p. 88. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "Top Country Vocalists" (PDF). Billboard. October 16, 1976. p. 10. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

Books

[edit]- Bufwack, Mary A.; Oermann, Robert K. (2003). Finding Her Voice: Women in Country Music: 1800–2000. Nashville, TN: The Country Music Press & Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 0-8265-1432-4.

- Shepard, Jean (2014). Down Through the Years. Don Wise Productions. ISBN 978-0944391068.

- Skinker, Chris (1995). "The Melody Ranch Girl (box set biography book)". Bear Family Records. BCD-15905-EI.

Notes

[edit]External links

[edit]- 1933 births

- 2016 deaths

- 20th-century American women singers

- 21st-century American women singers

- American autobiographers

- American women autobiographers

- American women country singers

- Bakersfield sound

- Capitol Records artists

- Country musicians from California

- Country musicians from Oklahoma

- Country Music Hall of Fame inductees

- Deaths from heart disease

- Deaths from Parkinson's disease in the United States

- Grand Ole Opry members

- Members of the Country Music Association

- Neurological disease deaths in Tennessee

- People from Pauls Valley, Oklahoma

- People from Visalia, California

- Singers from California

- Singers from Oklahoma

- United Artists Records artists

- American yodelers