Nutrient cycle

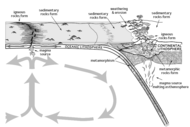

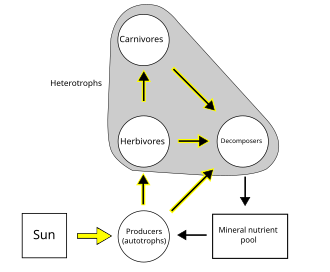

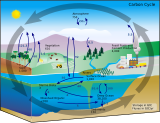

A nutrient cycle (or ecological recycling) is the movement and exchange of inorganic and organic matter back into the production of matter. Energy flow is a unidirectional and noncyclic pathway, whereas the movement of mineral nutrients is cyclic. Mineral cycles include the carbon cycle, sulfur cycle, nitrogen cycle, water cycle, phosphorus cycle, oxygen cycle, among others that continually recycle along with other mineral nutrients into productive ecological nutrition.

Overview

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Biogeochemical cycles |

|---|

|

The nutrient cycle is nature's recycling system. All forms of recycling have feedback loops that use energy in the process of putting material resources back into use. Recycling in ecology is regulated to a large extent during the process of decomposition.[1] Ecosystems employ biodiversity in the food webs that recycle natural materials, such as mineral nutrients, which includes water. Recycling in natural systems is one of the many ecosystem services that sustain and contribute to the well-being of human societies.[2][3][4]

There is much overlap between the terms for the biogeochemical cycle and nutrient cycle. Most textbooks integrate the two and seem to treat them as synonymous terms.[5] However, the terms often appear independently. The nutrient cycle is more often used in direct reference to the idea of an intra-system cycle, where an ecosystem functions as a unit. From a practical point, it does not make sense to assess a terrestrial ecosystem by considering the full column of air above it as well as the great depths of Earth below it. While an ecosystem often has no clear boundary, as a working model it is practical to consider the functional community where the bulk of matter and energy transfer occurs.[6] Nutrient cycling occurs in ecosystems that participate in the "larger biogeochemical cycles of the earth through a system of inputs and outputs."[6]: 425

All systems recycle. The biosphere is a network of continually recycling materials and information in alternating cycles of convergence and divergence. As materials converge or become more concentrated they gain in quality, increasing their potentials to drive useful work in proportion to their concentrations relative to the environment. As their potentials are used, materials diverge, or become more dispersed in the landscape, only to be concentrated again at another time and place.[7]: 2

Complete and closed loop

[edit]

Ecosystems are capable of complete recycling. Complete recycling means that 100% of the waste material can be reconstituted indefinitely. This idea was captured by Howard T. Odum when he penned that "it is thoroughly demonstrated by ecological systems and geological systems that all the chemical elements and many organic substances can be accumulated by living systems from background crustal or oceanic concentrations without limit as to concentration so long as there is available solar or another source of potential energy"[8]: 29 In 1979 Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen proposed the fourth law of entropy stating that complete recycling is impossible. Despite Georgescu-Roegen's extensive intellectual contributions to the science of ecological economics, the fourth law has been rejected in line with observations of ecological recycling.[9][10] However, some authors state that complete recycling is impossible for technological waste.[11]

Ecosystems execute closed loop recycling where demand for the nutrients that adds to the growth of biomass exceeds supply within that system. There are regional and spatial differences in the rates of growth and exchange of materials, where some ecosystems may be in nutrient debt (sinks) where others will have extra supply (sources). These differences relate to climate, topography, and geological history leaving behind different sources of parent material.[6][12] In terms of a food web, a cycle or loop is defined as "a directed sequence of one or more links starting from, and ending at, the same species."[13]: 185 An example of this is the microbial food web in the ocean, where "bacteria are exploited, and controlled, by protozoa, including heterotrophic microflagellates which are in turn exploited by ciliates. This grazing activity is accompanied by excretion of substances which are in turn used by the bacteria so that the system more or less operates in a closed circuit."[14]: 69–70

Ecological recycling

[edit]

An example of ecological recycling occurs in the enzymatic digestion of cellulose. "Cellulose, one of the most abundant organic compounds on Earth, is the major polysaccharide in plants where it is part of the cell walls. Cellulose-degrading enzymes participate in the natural, ecological recycling of plant material."[17] Different ecosystems can vary in their recycling rates of litter, which creates a complex feedback on factors such as the competitive dominance of certain plant species. Different rates and patterns of ecological recycling leaves a legacy of environmental effects with implications for the future evolution of ecosystems.[18]

A large fraction of the elements composing living matter reside at any instant of time in the world's biota. Because the earthly pool of these elements is limited and the rates of exchange among the various components of the biota are extremely fast with respect to geological time, it is quite evident that much of the same material is being incorporated again and again into different biological forms. This observation gives rise to the notion that, on the average, matter (and some amounts of energy) are involved in cycles.[19]: 219

Ecological recycling is common in organic farming, where nutrient management is fundamentally different compared to agri-business styles of soil management. Organic farms that employ ecosystem recycling to a greater extent support more species (increased levels of biodiversity) and have a different food web structure.[20][21] Organic agricultural ecosystems rely on the services of biodiversity for the recycling of nutrients through soils instead of relying on the supplementation of synthetic fertilizers.[22][23]

The model for ecological recycling agriculture adheres to the following principals:

- Protection of biodiversity.

- Use of renewable energy.

- Recycling of plant nutrients.[24]

Where produce from an organic farm leaves the farm gate for the market the system becomes an open cycle and nutrients may need to be replaced through alternative methods.

Ecosystem engineers

[edit]

The persistent legacy of environmental feedback that is left behind by or as an extension of the ecological actions of organisms is known as niche construction or ecosystem engineering. Many species leave an effect even after their death, such as coral skeletons or the extensive habitat modifications to a wetland by a beaver, whose components are recycled and re-used by descendants and other species living under a different selective regime through the feedback and agency of these legacy effects.[26][27] Ecosystem engineers can influence nutrient cycling efficiency rates through their actions.

Earthworms, for example, passively and mechanically alter the nature of soil environments. The bodies of dead worms passively contribute mineral nutrients to the soil. The worms also mechanically modify the physical structure of the soil as they crawl about (bioturbation) and digest on the molds of organic matter they pull from the soil litter. These activities transport nutrients into the mineral layers of soil. Worms discard wastes that create worm castings containing undigested materials where bacteria and other decomposers gain access to the nutrients. The earthworm is employed in this process and the production of the ecosystem depends on their capability to create feedback loops in the recycling process.[29][30]

Shellfish are also ecosystem engineers because they: 1) Filter suspended particles from the water column; 2) Remove excess nutrients from coastal bays through denitrification; 3) Serve as natural coastal buffers, absorbing wave energy and reducing erosion from boat wakes, sea level rise and storms; 4) Provide nursery habitat for fish that are valuable to coastal economies.[31]

Fungi contribute to nutrient cycling[32] and nutritionally rearrange patches of ecosystem creating niches for other organisms.[33] In that way fungi in growing dead wood allow xylophages to grow and develop and xylophages, in turn, affect dead wood, contributing to wood decomposition and nutrient cycling in the forest floor.[34]

History

[edit]

| Part of a series on the |

| Carbon cycle |

|---|

|

Nutrient cycling has a historical foothold in the writings of Charles Darwin in reference to the decomposition actions of earthworms. Darwin wrote about "the continued movement of the particles of earth".[28][36][37] Even earlier, in 1749 Carl Linnaeus wrote in "the economy of nature we understand the all-wise disposition of the creator in relation to natural things, by which they are fitted to produce general ends, and reciprocal uses" in reference to the balance of nature in his book Oeconomia Naturae.[38] In this book he captured the notion of ecological recycling: "The 'reciprocal uses' are the key to the whole idea, for 'the death, and destruction of one thing should always be subservient to the restitution of another;' thus mould spurs the decay of dead plants to nourish the soil, and the earth then 'offers again to plants from its bosom, what it has received from them.'"[39] The basic idea of a balance of nature, however, can be traced back to the Greeks: Democritus, Epicurus, and their Roman disciple Lucretius.[40]

Following the Greeks, the idea of a hydrological cycle (water is considered a nutrient) was validated and quantified by Halley in 1687. Dumas and Boussingault (1844) provided a key paper that is recognized by some to be the true beginning of biogeochemistry, where they talked about the cycle of organic life in great detail.[40][41] From 1836 to 1876, Jean Baptiste Boussingault demonstrated the nutritional necessity of minerals and nitrogen for plant growth and development. Prior to this time influential chemists discounted the importance of mineral nutrients in soil.[42] Ferdinand Cohn is another influential figure. "In 1872, Cohn described the 'cycle of life' as the "entire arrangement of nature" in which the dissolution of dead organic bodies provided the materials necessary for new life. The amount of material that could be molded into living beings was limited, he reasoned, so there must exist an "eternal circulation" (ewigem kreislauf) that constantly converts the same particle of matter from dead bodies into living bodies."[43]: 115–116 These ideas were synthesized in the Master's research of Sergei Vinogradskii from 1881-1883.[43]

Variations in terminology

[edit]In 1926 Vernadsky coined the term biogeochemistry as a sub-discipline of geochemistry.[40] However, the term nutrient cycle predates biogeochemistry in a pamphlet on silviculture in 1899: "These demands by no means pass over the fact that at places where sufficient quantities of humus are available and where, in case of continuous decomposition of litter, a stable, nutrient humus is present, considerable quantities of nutrients are also available from the biogenic nutrient cycle for the standing timber.[44]: 12 In 1898 there is a reference to the nitrogen cycle in relation to nitrogen fixing microorganisms.[45] Other uses and variations on the terminology relating to the process of nutrient cycling appear throughout history:

- The term mineral cycle appears early in a 1935 in reference to the importance of minerals in plant physiology: "...ash is probably either built up into its permanent structure, or deposited in some way as waste in the cells, and so may not be free to re-enter the mineral cycle."[46]: 301

- The term nutrient recycling appears in a 1964 paper on the food ecology of the wood stork: "While the periodic drying up and reflooding of the marshes creates special survival problems for organisms in the community, the fluctuating water levels favor rapid nutrient recycling and subsequent high rates of primary and secondary production"[47]: 97

- The term natural cycling appears in a 1968 paper on the transportation of leaf litter and its chemical elements for consideration in fisheries management: "Fluvial transport of tree litter from drainage basins is a factor in natural cycling of chemical elements and in the degradation of the land."[48]: 131

- The term ecological recycling appears in a 1968 publication on future applications of ecology for the creation of different modules designed for living in extreme environments, such as space or under the sea: "For our basic requirement of recycling vital resources, the oceans provide much more frequent ecological recycling than the land area. Fish and other organic populations have higher growth rates, vegetation has less capricious weather problems for sea harvesting."[49]

- The term bio-recycling appears in a 1976 paper on the recycling of organic carbon in oceans: "Following the actualistic assumption, then, that biological activity is responsible for the source of dissolved organic material in the oceans, but is not important for its activities after death of the organisms and subsequent chemical changes which prevent its bio-recycling, we can see no major difference in the behavior of dissolved organic matter between the prebiotic and postbiotic oceans."[50]: 414

Water is also a nutrient.[51] In this context, some authors also refer to precipitation recycling, which "is the contribution of evaporation within a region to precipitation in that same region."[52] These variations on the theme of nutrient cycling continue to be used and all refer to processes that are part of the global biogeochemical cycles. However, authors tend to refer to natural, organic, ecological, or bio-recycling in reference to the work of nature, such as it is used in organic farming or ecological agricultural systems.[24]

Recycling in novel ecosystems

[edit]An endless stream of technological waste accumulates in different spatial configurations across the planet and becomes hazardous in our soils, our streams, and our oceans.[53][54] This idea was similarly expressed in 1954 by ecologist Paul Sears: "We do not know whether to cherish the forest as a source of essential raw materials and other benefits or to remove it for the space it occupies. We expect a river to serve as both vein and artery carrying away waste but bringing usable material in the same channel. Nature long ago discarded the nonsense of carrying poisonous wastes and nutrients in the same vessels."[55]: 960 Ecologists use population ecology to model contaminants as competitors or predators.[56] Rachel Carson was an ecological pioneer in this area as her book Silent Spring inspired research into biomagnification and brought to the world's attention the unseen pollutants moving into the food chains of the planet.[57]

In contrast to the planet's natural ecosystems, technology (or technoecosystems) is not reducing its impact on planetary resources.[58][59] Only 7% of total plastic waste (adding up to millions upon millions of tons) is being recycled by industrial systems; the 93% that never makes it into the industrial recycling stream is presumably absorbed by natural recycling systems[60] In contrast and over extensive lengths of time (billions of years) ecosystems have maintained a consistent balance with production roughly equaling respiratory consumption rates. The balanced recycling efficiency of nature means that production of decaying waste material has exceeded rates of recyclable consumption into food chains equal to the global stocks of fossilized fuels that escaped the chain of decomposition.[61]

Pesticides soon spread through everything in the ecosphere-both human technosphere and nonhuman biosphere-returning from the 'out there' of natural environments back into plant, animal, and human bodies situated at the 'in here' of artificial environments with unintended, unanticipated, and unwanted effects. By using zoological, toxicological, epidemiological, and ecological insights, Carson generated a new sense of how 'the environment' might be seen.[62]: 62

Microplastics and nanosilver materials flowing and cycling through ecosystems from pollution and discarded technology are among a growing list of emerging ecological concerns.[63] For example, unique assemblages of marine microbes have been found to digest plastic accumulating in the world's oceans.[64] Discarded technology is absorbed into soils and creates a new class of soils called technosols.[65] Human wastes in the Anthropocene are creating new systems of ecological recycling, novel ecosystems that have to contend with the mercury cycle and other synthetic materials that are streaming into the biodegradation chain.[66] Microorganisms have a significant role in the removal of synthetic organic compounds from the environment empowered by recycling mechanisms that have complex biodegradation pathways. The effect of synthetic materials, such as nanoparticles and microplastics, on ecological recycling systems is listed as one of the major concerns for ecosystems in this century.[63][67]

Technological recycling

[edit]Recycling in human industrial systems (or technoecosystems) differs from ecological recycling in scale, complexity, and organization. Industrial recycling systems do not focus on the employment of ecological food webs to recycle waste back into different kinds of marketable goods, but primarily employ people and technodiversity instead. Some researchers have questioned the premise behind these and other kinds of technological solutions under the banner of 'eco-efficiency' are limited in their capability, harmful to ecological processes, and dangerous in their hyped capabilities.[11][68] Many technoecosystems are competitive and parasitic toward natural ecosystems.[61][69] Food web or biologically based "recycling includes metabolic recycling (nutrient recovery, storage, etc.) and ecosystem recycling (leaching and in situ organic matter mineralization, either in the water column, in the sediment surface, or within the sediment)."[70]: 243

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ohkuma, M. (2003). "Termite symbiotic systems: Efficient bio-recycling of lignocellulose". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 61 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1007/s00253-002-1189-z. PMID 12658509. S2CID 23331382.

- ^ Elser, J. J.; Urabe, J. (1999). "The stoichiometry of consumer-driven nutrient recycling: Theory, observations, and consequences" (PDF). Ecology. 80 (3): 735–751. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(1999)080[0735:TSOCDN]2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011.

- ^ Doran, J. W.; Zeiss, M. R. (2000). "Soil health and sustainability: Managing the biotic component of soil quality" (PDF). Applied Soil Ecology. 15 (1): 3–11. doi:10.1016/S0929-1393(00)00067-6. S2CID 42150903. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 August 2011.

- ^ Lavelle, P.; Dugdale, R.; Scholes, R.; Berhe, A. A.; Carpenter, E.; Codispoti, L.; et al. (2005). "12. Nutrient cycling" (PDF). Millennium Ecosystem Assessment: Objectives, Focus, and Approach. Island Press. ISBN 978-1-55963-228-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007.

- ^ Levin, Simon A; Carpenter, Stephen R; Godfray, Charles J; Kinzig, Ann P; Loreau, Michel; Losos, Jonathan B; Walker, Brian; Wilcove, David S (27 July 2009). The Princeton Guide to Ecology. Princeton University Press. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-691-12839-9.

- ^ a b c Bormann, F. H.; Likens, G. E. (1967). "Nutrient cycling" (PDF). Science. 155 (3761): 424–429. Bibcode:1967Sci...155..424B. doi:10.1126/science.155.3761.424. PMID 17737551. S2CID 35880562. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011.

- ^ Brown, M. T.; Buranakarn, V. (2003). "Emergy indices and ratios for sustainable material cycles and recycle options" (PDF). Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 38 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1016/S0921-3449(02)00093-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-13.

- ^ Odum, H. T. (1991). "Energy and biogeochemical cycles". In Rossi, C.; T., E. (eds.). Ecological physical chemistry. Amsterdam: Elsevier. pp. 25–26.

- ^ Cleveland, C. J.; Ruth, M. (1997). "When, where, and by how much do biophysical limits constrain the economic process?: A survey of Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen's contribution to ecological economics" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 22 (3): 203–223. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(97)00079-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2011.

- ^ Ayres, R. U. (1998). "Eco-thermodynamics: Economics and the second law". Ecological Economics. 26 (2): 189–209. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(97)00101-8.

- ^ a b Huesemann, M. H. (2003). "The limits of technological solutions to sustainable development" (PDF). Clean Techn Environ Policy. 5: 21–34. doi:10.1007/s10098-002-0173-8. S2CID 55193459. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2011.

- ^ Smaling, E.; Oenema, O.; Fresco, L., eds. (1999). "Nutrient cycling in ecosystems versus nutrient budgets in agricultural systems" (PDF). Nutrient cycles and nutrient budgets in global agro-ecosystems. Wallingford, UK: CAB International. pp. 1–26.

- ^ Roughgarden, J.; May, R. M.; Levin, S. A., eds. (1989). "13. Food webs and community structure". Perspectives in ecological theory. Princeton University Press. pp. 181–202. ISBN 978-0-691-08508-1.

- ^ Legendre, L.; Levre, J. (1995). "Microbial food webs and the export of biogenic carbon in oceans" (PDF). Aquatic Microbial Ecology. 9: 69–77. doi:10.3354/ame009069.

- ^ Kormondy, E. J. (1996). Concepts of ecology (4th ed.). New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. p. 559. ISBN 978-0-13-478116-7.

- ^ Proulx, S. R.; Promislow, D. E. L.; Phillips, P. C. (2005). "Network thinking in ecology and evolution" (PDF). Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 20 (6): 345–353. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.04.004. PMID 16701391. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2011.

- ^ Rouvinen, J.; Bergfors, T.; Teeri, T.; Knowles, J. K. C.; Jones, T. A. (1990). "Three-dimensional structure of cellobiohydrolase II from Trichoderma reesei". Science. 249 (4967): 380–386. Bibcode:1990Sci...249..380R. doi:10.1126/science.2377893. JSTOR 2874802. PMID 2377893.

- ^ Clark, B. R.; Hartley, S. E.; Suding, K. N.; de Mazancourt, C. (2005). "The effect of recycling on plant competitive hierarchies". The American Naturalist. 165 (6): 609–622. doi:10.1086/430074. JSTOR 3473513. PMID 15937742. S2CID 22662199.

- ^ Ulanowicz, R. E. (1983). "Identifying the structure of cycling in ecosystems" (PDF). Mathematical Biosciences. 65 (2): 219–237. doi:10.1016/0025-5564(83)90063-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-28.

- ^ Stockdale, E. A.; Shepherd, M. A.; Fortune, S.; Cuttle, S. P. (2006). "Soil fertility in organic farming systems – fundamentally different?". Soil Use and Management. 18 (S1): 301–308. doi:10.1111/j.1475-2743.2002.tb00272.x. S2CID 98097371.

- ^ Macfadyen, S.; Gibson, R.; Polaszek, A.; Morris, R. J.; Craze, P. G.; Planque, R.; et al. (2009). "Do differences in food web structure between organic and conventional farms affect the ecosystem service of pest control?". Ecology Letters. 12 (3): 229–238. Bibcode:2009EcolL..12..229M. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01279.x. PMID 19141122. S2CID 25635323.

- ^ Altieri, M. A. (1999). "The ecological role of biodiversity in agroecosystems" (PDF). Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment. 74 (1–3): 19–31. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.588.7418. doi:10.1016/S0167-8809(99)00028-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2011.

- ^ Mäder, P. (2005). "Sustainability of organic and integrated farming (DOK trial)" (PDF). In Rämert, B.; Salomonsson, L.; Mäder, P. (eds.). Ecosystem services as a tool for production improvement in organic farming – the role and impact of biodiversity. Uppsala: Centre for Sustainable Agriculture, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-91-576-6881-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-07-13. Retrieved 2011-06-21.

- ^ a b Larsson, M.; Granstedt, A. (2010). "Sustainable governance of the agriculture and the Baltic Sea: Agricultural reforms, food production and curbed eutrophication". Ecological Economics. 69 (10): 1943–1951. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.05.003.

- ^ Roman, J.; McCarthy, J. J. (2010). "The whale pump: Marine mammals enhance primary productivity in a coastal basin". PLOS ONE. 5 (10): e13255. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...513255R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013255. PMC 2952594. PMID 20949007.

- ^ Laland, K.; Sterelny, K. (2006). "Perspective: Several reasons (not) to neglect niche construction". Evolution. 60 (9): 1751–1762. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2006.tb00520.x. PMID 17089961. S2CID 22997236.

- ^ Hastings, A.; Byers, J. E.; Crooks, J. A.; Cuddington, K.; Jones, C. G.; Lambrinos, J. G.; et al. (February 2007). "Ecosystem engineering in space and time". Ecology Letters. 10 (2): 153–164. Bibcode:2007EcolL..10..153H. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00997.x. PMID 17257103. S2CID 44870405.

- ^ a b Darwin, C. R. (1881). "The formation of vegetable mould, through the action of worms, with observations on their habits". London: John Murray.

- ^ Barot, S.; Ugolini, A.; Brikci, F. B. (2007). "Nutrient cycling efficiency explains the long-term effect of ecosystem engineers on primary production". Functional Ecology. 21: 1–10. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2006.01225.x.

- ^ Yadava, A.; Garg, V. K. (2011). "Recycling of organic wastes by employing Eisenia fetida". Bioresource Technology. 102 (3): 2874–2880. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2010.10.083. PMID 21078553.

- ^ The Nature Conservancy. "Oceans and Coasts Shellfish Reefs at Risk: Critical Marine Habitats". Archived from the original on 4 October 2013.

- ^ Boddy, Lynne; Watkinson, Sarah C. (31 December 1995). "Wood decomposition, higher fungi, and their role in nutrient redistribution". Canadian Journal of Botany. 73 (S1): 1377–1383. doi:10.1139/b95-400. ISSN 0008-4026.

- ^ Filipiak, Michał; Sobczyk, Łukasz; Weiner, January (9 April 2016). "Fungal Transformation of Tree Stumps into a Suitable Resource for Xylophagous Beetles via Changes in Elemental Ratios". Insects. 7 (2): 13. doi:10.3390/insects7020013. PMC 4931425.

- ^ Filipiak, Michał; Weiner, January (1 September 2016). "Nutritional dynamics during the development of xylophagous beetles related to changes in the stoichiometry of 11 elements" (PDF). Physiological Entomology. 42: 73–84. doi:10.1111/phen.12168. ISSN 1365-3032.

- ^ Montes, F.; Cañellas, I. (2006). "Modelling coarse woody debris dynamics in even-aged Scots pine forests". Forest Ecology and Management. 221 (1–3): 220–232. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2005.10.019.

- ^ Stauffer, R. C. (1960). "Ecology in the long manuscript version of Darwin's "Origin of Species" and Linnaeus' "Oeconomy of Nature"". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 104 (2): 235–241. JSTOR 985662.

- ^ Worster, D. (1994). Nature's economy: A history of ecological ideas (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 423. ISBN 978-0-521-46834-3.

- ^ Linnaeus, C. (1749). London, R.; Dodsley, J. (eds.). Oeconomia Naturae [defended by I. Biberg]. Holmiae: Laurentium Salvium (in Latin). Vol. 2 (Translated by Benjamin Stillingfleet as 'The Oeconomy of Nature,' in Miscellaneous Tracts relating to Natural History, Husbandry, and Physick. ed.). Amoenitates Academicae, seu Dissertationes Variae Physicae, Medicae, Botanicae. pp. 1–58.

- ^ Pearce, T. (2010). "A great complication of circumstances" (PDF). Journal of the History of Biology. 43 (3): 493–528. doi:10.1007/s10739-009-9205-0. PMID 20665080. S2CID 34864334. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-31. Retrieved 2011-06-21.

- ^ a b c Gorham, E. (1991). "Biogeochemistry: Its origins and development" (PDF). Biogeochemistry. 13 (3): 199–239. doi:10.1007/BF00002942. S2CID 128563314. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- ^ Dumas, J.; Boussingault, J. B. (1844). Gardner, J. B. (ed.). The chemical and physical balance of nature (3rd ed.). New York: Saxton and Miles.

- ^ Aulie, R. P. (1974). "The mineral theory". Agricultural History. 48 (3): 369–382. JSTOR 3741855.

- ^ a b Ackert, L. T. Jr. (2007). "The "Cycle of Life" in Ecology: Sergei Vinogradskii's soil microbiology, 1885-1940". Journal of the History of Biology. 40 (1): 109–145. doi:10.1007/s10739-006-9104-6. JSTOR 29737466. S2CID 128410978.

- ^ Pamphlets on silviculture, vol. 41, The University of California, 1899

- ^ Springer on behalf of Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (1898). "The advances made in agricultural chemistry during the last twenty-five years". Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information (Royal Gardens, Kew). 1898 (144): 326–331. doi:10.2307/4120250. JSTOR 4120250.

- ^ Penston, N. L. (1935). "Studies of the physiological importance of the mineral elements in plants VIII. The variation in potassium content of potato leaves during the day". New Phytologist. 34 (4): 296–309. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1935.tb06848.x. JSTOR 2428425.

- ^ Kahl, M. P. (1964). "Food ecology of the wood stork (Mycteria americana) in Florida". Ecological Monographs. 34 (2): 97–117. Bibcode:1964EcoM...34...97K. doi:10.2307/1948449. JSTOR 1948449.

- ^ Slack, K. V.; Feltz, H. R. (1968). "Tree leaf control on low flow water quality in a small Virginia stream". Environmental Science and Technology. 2 (2): 126–131. Bibcode:1968EnST....2..126S. doi:10.1021/es60014a005.

- ^ McHale, J. (1968). "Toward the future". Design Quarterly. 72 (72): 3–31. doi:10.2307/4047350. JSTOR 4047350.

- ^ Nissenbaum, A. (1976). "Scavenging of soluble organic matter from the prebiotic oceans". Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres. 7 (4): 413–416. Bibcode:1976OrLi....7..413N. doi:10.1007/BF00927936. PMID 1023140. S2CID 31672324.

- ^ Martina, M. M.; Hoff, M. V. (1988). "The cause of reduced growth of Manduca sexta larvae on a low-water diet: Increased metabolic processing costs or nutrient limitation?" (PDF). Journal of Insect Physiology. 34 (6): 515–525. doi:10.1016/0022-1910(88)90193-X. hdl:2027.42/27572.

- ^ Eltahir, E. A. B.; Bras, R. L. (1994). "Precipitation recycling in the Amazon basin" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 120 (518): 861–880. Bibcode:1994QJRMS.120..861E. doi:10.1002/qj.49712051806.

- ^ Derraik, J. G. B. (2002). "The pollution of the marine environment by plastic debris: A review". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 44 (9): 842–852. Bibcode:2002MarPB..44..842D. doi:10.1016/s0025-326x(02)00220-5. PMID 12405208.

- ^ Thompson, R. C.; Moore, C. J.; vom Saal, F. S.; Swan, S. H. (2009). "Plastics, the environment and human health: current consensus and future trends". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 364 (1526): 2153–2166. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0053. PMC 2873021. PMID 19528062.

- ^ Sears, P. B. (1954). "Human ecology: A problem in synthesis". Science. 120 (3128): 959–963. Bibcode:1954Sci...120..959S. doi:10.1126/science.120.3128.959. JSTOR 1681410. PMID 13216198.

- ^ Rohr, J. R.; Kerby, J. L.; Sih, A. (2006). "Community ecology as a framework for predicting contaminant effects" (PDF). Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 21 (11): 606–613. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2006.07.002. PMID 16843566.

- ^ Gray, J. S. (2002). "Biomagnification in marine systems: the perspective of an ecologist" (PDF). Marine Pollution Bulletin. 45 (1–12): 46–52. Bibcode:2002MarPB..45...46G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.566.960. doi:10.1016/S0025-326X(01)00323-X. PMID 12398366. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- ^ Huesemann, M. H. (2004). "The failure of eco-efficiency to guarantee sustainability: Future challenges for industrial ecology". Environmental Progress. 23 (4): 264–270. doi:10.1002/ep.10044.

- ^ Huesemann, M. H.; Huesemann, J. A. (2008). "Will progress in science and technology avert or accelerate global collapse? A critical analysis and policy recommendations". Environment, Development and Sustainability. 10 (6): 787–825. doi:10.1007/s10668-007-9085-4. S2CID 154637064.

- ^ Siddique, R.; Khatib, J.; Kaur, I. (2008). "Use of recycled plastic in concrete: A review". Waste Management. 28 (10): 1835–1852. Bibcode:2008WaMan..28.1835S. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2007.09.011. PMID 17981022.

- ^ a b Odum, E. P.; Barrett, G. W. (2005). Fundamentals of ecology. Brooks Cole. p. 598. ISBN 978-0-534-42066-6.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Luke, T. W. (1995). "On environmentality: Geo-Power and eco-knowledge in the discourses of contemporary environmentalism". The Politics of Systems and Environments, Part II. 31 (31): 57–81. doi:10.2307/1354445. JSTOR 1354445.

- ^ a b Sutherland, W. J.; Clout, M.; Côte, I. M.; Daszak, P.; Depledge, M. H.; Fellman, L.; et al. (2010). "A horizon scan of global conservation issues for 2010" (PDF). Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 25 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2009.10.003. hdl:1826/8674. PMC 3884124. PMID 19939492.

- ^ Zaikab, G. D. (2011). "Marine microbes digest plastic". Nature News. doi:10.1038/news.2011.191.

- ^ Rossiter, D. G. (2007). "Classification of Urban and Industrial Soils in the World Reference Base for Soil Resources (5 pp)" (PDF). Journal of Soils and Sediments. 7 (2): 96–100. doi:10.1065/jss2007.02.208. S2CID 10338446.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Meybeck, M. (2003). "Global analysis of river systems: from Earth system controls to Anthropocene syndromes". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 358 (1440): 1935–1955. doi:10.1098/rstb.2003.1379. PMC 1693284. PMID 14728790.

- ^ Bosma, T. N. P.; Harms, H.; Zehnder, A. J. B. (2001). "Biodegradation of Xenobiotics in Environment and Technosphere". The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry. Vol. 2K. pp. 163–202. doi:10.1007/10508767_2. ISBN 978-3-540-62576-6.

- ^ Rees, W. E. (2009). "The ecological crisis and self-delusion: implications for the building sector". Building Research & Information. 37 (3): 300–311. doi:10.1080/09613210902781470.

- ^ Pomeroy, L. R. (1970). "The strategy of mineral cycling". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1: 171–190. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.01.110170.001131. JSTOR 2096770.

- ^ Romero, J.; Lee, K.; Pérez, M.; Mateo, M. A.; Alcoverro, T. (22 February 2007). "9. Nutrient dynamics in seagrass ecosystems.". In Larkum, A. W. D.; Orth, R. J.; Duarte, C. M. (eds.). Seagrasses: Biology, Ecology and Conservation. Springer. pp. 227–270. ISBN 9781402029424.