Narcissus (mythology)

| Narcissus | |

|---|---|

Narcissus, fresco from the House of M. Lucretius Fronto at Pompeii | |

| Abode | Thespiae |

| Symbol | Daffodil |

| Parents | Cephissus and Liriope or Endymion and Selene |

| Part of a series on |

| Greek mythology |

|---|

|

| Deities |

| Heroes and heroism |

| Related |

|

|

In Greek mythology, Narcissus (/nɑːrˈsɪsəs/; Ancient Greek: Νάρκισσος, romanized: Nárkissos) was a hunter from Thespiae in Boeotia (alternatively Mimas or modern day Karaburun, Izmir) who was known for his beauty which was noticed by all. According to the best known version of the story, by Ovid, Narcissus rejected all advances, eventually falling in love with a reflection in a pool of water, tragically not realizing its similarity, entranced by it. In some versions, he beat his breast purple in agony at being kept apart from this reflected love, and in his place sprouted a flower bearing his name.

The character of Narcissus is the origin of the term narcissism, a self-centered personality style. This quality in extreme contributes to the definition of narcissistic personality disorder, a psychiatric condition marked by grandiosity, excessive need for attention and admiration, and an inability to empathize.

Etymology

[edit]The name is of Greek etymology. According to R. S. P. Beekes, "[t]he suffixes [-ισσος] clearly points to a Pre-Greek word."[1] The word narcissus has come to be used for the daffodil, but there is no clarity on whether the flower is named for the myth or the myth for the flower, or if there is any true connection at all. Pliny the Elder wrote that the plant was named for its fragrance (ναρκάω narkao, "I grow numb"), not the mythological character.

Family

[edit]In some versions, Narcissus was the son of the river god Cephissus and nymph Liriope,[2] while Nonnus instead has him as the son of the lunar goddess Selene and her mortal lover Endymion.[3]

Mythology

[edit]Several versions of the myth have survived from ancient sources, one from the Greek traveler and geographer of the second century AD Pausanias and a more popular one by Ovid, published before 8 AD, found in Book 3 of his Metamorphoses. This is the story of Echo and Narcissus, a story within another story. The framing in Ovid shows the story is a test of the prophetic abilities of Tiresias, an individual who had been both a man and a woman, and whose sight was taken from him during a contest between Juno and Jove. He had taken Jove's side and Juno, angered, blinded him. In its place, Jove gave him future sight, or prophecy. The prophecy which made Tiresias' name for him was the story of Echo and Narcissus.

After being "ravaged" by the river god Cephissus, the nymph Liriope gave birth to Narcissus "beautiful even as a child." As was apparently custom, she consulted the seer Tiresias about the boy's future, who predicted that the boy would live a long life only if he never "came to know himself". During his 16th year, after getting lost while hunting with friends, Narcissus came to be followed by a nymph Echo.

Echo, an Oread (mountain nymph), like Tiresias, had a sensory ability altered after an argument between Juno and Jove. Echo had kept Juno "occupied" with gossip while Jove had an affair behind her back. In another similar version by Ovid, it was said that Echo kept the goddess Hera occupied with stories while Zeus' lovers escaped Mt. Olympus.[4] As a punishment, Juno and Hera both took from Echo her agency in speech; Echo was, thereafter, never able to speak unless it was to repeat the last few words of those she heard. Echo had deceived using gossip; she would be condemned to be only that from then on.

Meanwhile, Echo spied Narcissus, separated from his hunting friends, and she become immediately infatuated, following him, waiting for him to speak so her feelings might be heard. Narcissus sensed he was being followed and shouted "Who's there?" Echo repeated "Who's there?" After a few rounds of this, in which Narcissus' confusion and frustrations mounts, Echo came close enough so that she was revealed, and attempted to embrace him. Horrified, he stepped back and told her to "keep her chains". Echo was heartbroken and she wasted away, losing her body amidst lonely glens, until nothing but her chaste verbal ability remained of her.

Nemesis, the goddess of revenge, heard the pleas of a young man, Ameinias, who had fallen for Narcissus but was ignored and cursed him; Nemesis listened, proclaiming that Narcissus would never be able to be loved by the one he fell in love with.

Thus, in the same, long, lost journey narrated by Ovid, after spurning Echo and the young man, Narcissus was getting thirsty. He finds a pool of water which Ovid tells us no animal had ever approached. Leaning down to drink, Narcissus sees a reflection. Ovid, inhabiting Narcissus' mindset, describes what he sees as being as beautiful as a marble statue. Narcissus did not realize it was his own reflection and fell deeply in love with it, as if it were someone else; in this way, Tiresias' prophecy came true in the same instance as did Nemesis' curse.[5][a][b] Unable to leave the allure of this image, Narcissus eventually realized that his love could not be reciprocated and he melted away from the fire of passion burning inside him, eventually turning into a gold and white flower.[6][7]

An earlier version ascribed to the poet Parthenius of Nicaea, composed around 50 BC, was discovered in 2004 by Dr Benjamin Henry among the Oxyrhynchus papyri at Oxford.[8][9] Again, like in Ovid, Narcissus lost his will to live and committed suicide. A version by Conon, a contemporary of Ovid, also ends in suicide (Narrations, 24). In it, a young man named Ameinias fell in love with Narcissus, who had already spurned his male suitors. Narcissus also spurned him and gave him a sword. Ameinias committed suicide at Narcissus's doorstep. He had prayed to the gods to give Narcissus a lesson for all the pain he provoked. Narcissus walked by a pool of water and decided to drink some. He saw his reflection, became entranced by it, and killed himself because he could not have his object of desire. Because of this tragedy, the Thespians came to honor and reverence Eros especially among the gods.[10][6] A century later the travel writer Pausanias recorded a novel variant of the story, in which Narcissus falls in love with his twin sister rather than himself.[10][11] In all versions, his body disappears and all that is left is a narcissus flower.

Influence on culture

[edit]The myth of Narcissus has inspired artists for at least two thousand years, even before the Roman poet Ovid featured a version in book III of his Metamorphoses. This was followed in more recent centuries by other poets (e.g. Keats and Alfred Edward Housman) and painters (Caravaggio, Poussin, Turner, Dalí (see Metamorphosis of Narcissus), and Waterhouse).

Literature

[edit]

The myth had a decided influence on English Victorian homoerotic culture, via André Gide's study of the myth, Le Traité du Narcisse ('The Treatise of the Narcissus', 1891), and the only novel by Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray.

Paulo Coelho's The Alchemist also starts with a story about Narcissus, found (we are told) by the alchemist in a book brought by someone in the caravan. The alchemist's (and Coelho's) source was very probably Hesketh Pearson's The Life of Oscar Wilde (1946) in which this story is recorded (Penguin edition, p. 217) as one of Wilde's inspired inventions. This version of the Narcissus story is based on Wilde's "The Disciple" from his "Poems in Prose (Wilde) ".

Author and poet Rainer Maria Rilke visits the character and symbolism of Narcissus in several of his poems.

Seamus Heaney references Narcissus in his poem "Personal Helicon"[12] from his first collection "Death of a Naturalist":

To stare, big-eyed Narcissus, into some spring

Is beneath all adult dignity.

In Rick Riordan's Heroes of Olympus series, Narcissus appears as a minor antagonist in the third book The Mark of Athena.

William Faulkner's character "Narcissa" in Sanctuary, sister of Horace Benbow, was also named after Narcissus. Throughout the novel, she allows the arrogant, pompous pressures of high-class society to overrule the unconditional love that she should have for her brother.

Hermann Hesse's character "Narcissus" in "Narcissus and Goldmund" shares several of mythical Narcissus' traits, although his narcissism is based on his intellect rather than his physical beauty.

A. E. Housman refers to the 'Greek Lad', Narcissus, in his poem "Look not in my Eyes" from A Shropshire Lad set to music by several English composers including George Butterworth. At the end of the poem stands a jonquil, a variety of daffodil, Narcissus jonquilla, which like Narcissus looks sadly down into the water.

Herman Melville references the myth of Narcissus in his novel Moby-Dick, in which Ishmael explains the myth as "the key to it all," referring to the greater theme of finding the essence of Truth through the physical world.

On Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen's A Fada Oriana, the eponymous protagonist is punished with mortality for abandoning her duties in order to stare at herself in the surface of a river.

Joseph Conrad's novel The Nigger of the 'Narcissus' features a merchant ship named Narcissus. An incident involving the ship, and the difficult decisions made by the crew, explore themes involving self-interest vs. altruism and humanitarianism.

Naomi Iizuka's play Polaroid Stories, a contemporary rewrite of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth, features Narcissus as a character. In the play he is portrayed as a self obsessed, and drug addicted young man who was raised on the streets. He is alluded to being a member of the LGBT+ community and mentions his sexual endeavours with older men, some ending with the death of these men due to drug overdoses. He is accompanied by the character Echo, whom he continuously spurns.

Music

[edit]- In Gilbert and Sullivan's opera Patience, the ldyllic poet Archibald Grosvenor calls himself "a very Narcissus" after gazing at his own reflection.[13]

- Composer Nikolai Tcherepnin wrote his ballet "Narcisse et Echo, Op. 40" in 1911 for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes and was danced by Nijinski.

- The fifth of Benjamin Britten's Six Metamorphoses after Ovid for solo oboe (1951) is titled "Narcissus", "who fell in love with his own image and became a flower".

Visual art

[edit]Narcissus has been a subject for many painters such as Caravaggio, Poussin, Turner, Dalí, Waterhouse, Carpioni, Lagrenée, and Roos.

-

Echo And Narcissus, John William Waterhouse

-

Liriope Bringing Narcissus before Tiresias, Giulio Carpioni

-

Echo and Narcissus, Louis-Jean-François Lagrenée

-

Narcissus, follower of Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio

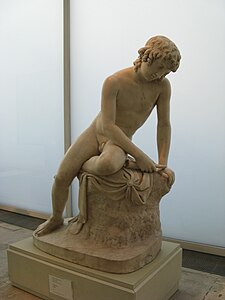

Sculptors such as Paul Dubois, John Gibson, Henri-Léon Gréber, Benvenuto Cellini and Hubert Netzer have sculpted Narcissus.[14]

-

Narcisse, Paul Dubois

-

Narcissus, John Gibson

-

Narziss, Hubert Netzer

-

Narcissus, possibly Valerio Cioli

-

Narcisse, Henri-Léon Gréber

-

Narcisse, Benvenuto Cellini

-

Narcisse, Gabriel Grupello and Albert Desenfans

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Narcissus is in danger when he sees the image but not, because of that, lost. He is lost when he recognizes himself in the image. It is not until then that death becomes the only possible solution. Narcissus dies when he loses the illusion but cannot escape from the feeling that it has aroused; he dies when there is no hope left that the passion can be satisfied. — Vinge (1967a)[5]

- ^

Finally Narcissus realizes that he has come across an insoluble problem and gives it a concise formulation : [Ovid writes] "Quod cupio, mecum est: Inopem me copia fecit."

- [Translation: "What I desire is with me: I was destitute and made abundant.]

- [Translation: "He sees through who he has in front of him in the water; he neither loves his reflection, like one reader follows another, nor does he practice 'narcissism', as has been misunderstood since Freud"]49.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 997.

- ^ "The myth of Narcissus". 2 August 2009.

- ^ Nonnus, Dionysiaca 48.581 ff.

- ^ Cartwright, Mark (5 March 2023). "Narcissus". World History Encyclopedia.

- ^ a b c Vinge, Louise (1967a). "The Narcissus Myth in Western Literature up until the Early 19th Century". litteraturbanken.se. Gleerups.

- ^ a b "The myth of Narcissus".

- ^ Tzetzes, John. "Chiliades, 1.9". lines 235–238.

- ^ Keys, David (May 2004). "Ancient manuscript sheds new light on an enduring myth". BBC History Magazine. Vol. 5, no. 5. p. 9. Retrieved 30 April 2010 – via Papyrology / University of Oxford.

- ^ Keys, David (1 May 2004). "The ugly end of Narcissus". Poxy: Oxyrhynchus Online. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ a b "ToposText". topostext.org. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ Jacoby, Mario (1991). Individuation and Narcissism: The psychology of self in Jung and Kohut (1st ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0415064644.

- ^ Cf. Ibiblio, Internet Poetry Archive: Text of the Poem Personal Helicon

- ^ Glinert, Ed, ed. (2006). The Complete Gilbert and Sullivan. Penguin Books. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-713-99860-3.

- ^ "Paul Dubois, Narcisse, Orsay". Archived from the original on 1 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

Modern sources

[edit]- Graves, R. (1968). The Greek Myths. London, UK: Cassell.

- Gantz, T. (1993). Early Greek Myth. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Kerényi, K. (1959). The Heroes of the Greeks. New York, NY / London, UK: Thames and Hudson.

- Vinge, Louise (1967). The Narcissus Theme in Western Literature up to the Early 19th Century.

- Calimach, A. (2001). Lovers' Legends: The gay Greek myths. New Rochelle, NY: Haiduk Press. ISBN 9780971468603. On-line version

- Alexander, M. (2012). Narcissus. available online

External links

[edit]- "Images of Narcissus". Iconographic Database. The Warburg Institute.

Media related to Narcissus (mythology) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Narcissus (mythology) at Wikimedia Commons- Henry, W. B. (n.d.). "New light on the Narcissus myth (P.Oxy. LXIX 4711)". Articles. Papyrology. Oxford, UK: University of Oxford.