Stoney language

| Stoney | |

|---|---|

| Nakoda, Nakota, Isga, Îyethka Îabi, Îyethka wîchoîe, Isga Iʔabi | |

| Native to | Canada |

| Ethnicity | Nakota: Stoney |

Native speakers | 3,025 (2016)[1] |

Siouan

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | sto |

| Glottolog | ston1242 |

| ELP | Stoney |

The location of Stoney / Nakoda | |

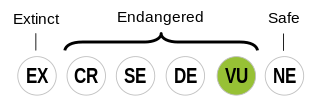

Stoney is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

| Nakota / Nakoda // Îyârhe[2] "ally / friend" // "mountain" | |

|---|---|

| Person | Îyethka[3] |

| People | Îyethkabi (Îyethka Oyade) |

| Language | Îyethka Îabi / wîchoîe Îyethka Wowîhâ[4] |

| Country | Îyethka Makóce |

Stoney—also called Nakota, Nakoda, Isga, and formerly Alberta Assiniboine—is a member of the Dakota subgroup of the Mississippi Valley grouping of the Siouan languages.[5] The Dakotan languages constitute a dialect continuum consisting of Santee-Sisseton (Dakota), Yankton-Yanktonai (Dakota), Teton (Lakota), Assiniboine, and Stoney.[6]

Stoney is the most linguistically divergent of the Dakotan dialects[7] and has been described as "on the verge of becoming a separate language."[citation needed] Ullrich considers Stoney and Assiniboine distinct languages, saying "The Nakoda language spoken by the Assiniboine is not intelligible to Lakota and Dakota speakers, unless they have been exposed to it extensively. The Stoney form of the Nakoda language is completely unintelligible to Lakota and Dakota speakers. As such, the two Nakoda languages cannot be considered dialects of the Lakota and Dakota language."[8] The Stoneys are the only Siouan people that live entirely in Canada,[6] and the Stoney language is spoken by five groups in Alberta.[9][7] No official language survey has been undertaken for every community where Stoney is spoken, but the language may be spoken by as many as a few thousand people, primarily at the Morley community.[10]

Relationship to Assiniboine

[edit]Stoney's closest linguistic relative is Assiniboine.[11] The two have often been confused with each other due to their close historical and linguistic relationship, but they are not mutually intelligible.[5] Stoney either developed from Assiniboine, or both Stoney and Assiniboine developed from a common ancestor language.[10][12]

Phonology

[edit]Very little linguistic documentation and descriptive research has been done on Stoney. However, Stoney varieties demonstrate broad phonological similarity with some important divergences.

Morley Dialect

[edit]For example, the following phonemes are reportedly found in Morley Stoney, spoken on the Morley Reserve:

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Pharyngeal | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive/ Affricate |

voiceless | p ⟨p⟩ | t ⟨t⟩ | t͡ʃ ⟨ch⟩ | k ⟨k⟩ | ||

| voiced | b ⟨b⟩ | d ⟨d⟩ | d͡ʒ ⟨j⟩ | ɡ ⟨g⟩ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | s ⟨s⟩ | ʃ ⟨sh⟩ | ħ ⟨rh⟩ | h ⟨h⟩ | ||

| voiced | z ⟨z⟩ | ʒ ⟨zh⟩ | ʕ ⟨r⟩ | ||||

| Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | |||||

| Semivowel | w ⟨w⟩ | j ⟨y⟩ | |||||

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i, ĩ | u, ũ | |

| Mid | e | o | |

| Low | a, ã |

Alexis Dialect

[edit]For comparison, these phonemes reportedly characterize the Stoney spoken at Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation, which maintains the common Siouan three-way contrast[5] between plain, aspirated, and ejective stops:

| Bilabial | Dental | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive/ Affricate |

plain | p ⟨b⟩ | t ⟨d⟩ | t͡ʃ ⟨j⟩ | k ⟨g⟩ | ʔ ⟨ʔ⟩ |

| aspirated | pʰ ⟨p⟩ | tʰ ⟨t⟩ | t͡ʃʰ ⟨c⟩ | kʰ ⟨k⟩ | ||

| ejective | pʼ ⟨p'⟩ | tʼ ⟨t'⟩ | t͡ʃʼ ⟨c'⟩ | kʼ ⟨k'⟩ | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | s ~ θ ⟨s⟩ | ʃ ⟨sh⟩ | x ⟨x⟩ | h ⟨h⟩ | |

| voiced | z ~ ð ⟨z⟩ | ʒ ⟨zh⟩ | ɣ ⟨r⟩ | |||

| Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | ||||

| Semivowel | w ⟨w⟩ | j ⟨y⟩ | ||||

Notice that Alexis Stoney, for example, has innovated contrastive vowel length, which is not found in other Dakotan dialects.[10] Alexis Stoney also has long and nasal mid vowels:[12]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i, iː, ĩ | u, uː, ũ | |

| Mid | e, eː, ẽ | o, oː, õ | |

| Low | a, aː, ã |

Writing system

[edit]| a | â | b | ch | d | e | g | h | i | î | j | k | m | n | o | p | r | rh | s | sh | t | u | û | w | y | z | zh |

| a | â | aa | b | c | c' | d | e | ê | ee | g | h | i | î | ii | j | k | k' | m | n | o | ô | oo | p | p' | r | s | sh | t | t' | u | û | uu | w | x | y | z | zh | ʔ |

Word set (includes numbers)

[edit]- One — Wazhi

- Two — Nûm

- Three — Yamnî

- Four — Ktusa

- Five — Zaptâ

- Man — Wîca

- Woman — Wîyâ

- Sun — Wa

- Moon — Hâwi

- Water — Mini

Phonetic differences from other Dakotan languages

[edit]The following table shows some of the main phonetic differences between Stoney, Assiniboine, and the three dialects (Lakota, Yankton-Yanktonai and Santee-Sisseton) of Sioux.[8][6]

| Sioux | Nakota | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lakota | Western Dakota | Eastern Dakota | Assinibione | Stoney | gloss | ||

| Yanktonai | Yankton | Sisseton | Santee | ||||

| Lakȟóta | Dakȟóta | Dakhóta | Nakhóta | Nakhóda | self-designation | ||

| lowáŋ | dowáŋ | dowáŋ | nowáŋ | 'to sing' | |||

| ló | dó | dó | nó | 'assertion' | |||

| čísčila | čísčina | čístina | čúsina | čúsin | 'small' | ||

| hokšíla | hokšína | hokšína | hokšída | hokšína | hokšín | 'boy' | |

| gnayáŋ | gnayáŋ | knayáŋ | hnayáŋ | knayáŋ | hna | 'to deceive' | |

| glépa | gdépa | kdépa | hdépa | knépa | hnéba | 'to vomit' | |

| kigná | kigná | kikná | kihná | kikná | gihná | 'to soothe' | |

| slayá | sdayá | sdayá | snayá | snayá | 'to grease' | ||

| wičháša | wičháša | wičhášta | wičhášta | wičhá | 'man' | ||

| kibléza | kibdéza | kibdéza | kimnéza | gimnéza | 'to sober up' | ||

| yatkáŋ | yatkáŋ | yatkáŋ | yatkáŋ | yatkáŋ | 'to drink' | ||

| hé | hé | hé | žé | žé | 'that' | ||

References

[edit]- ^ "Census Profile, 2016 Census". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ "Mountain". Stoney Nakoda Dictionary Online. Stoney Education Authority. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ "Stoney Nakoda". Stoney Nakoda Dictionary Online. Stoney Education Authority. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ "wowîhâ". Stoney Nakoda Dictionary Online. Stoney Education Authority. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ a b c Parks, Douglas R.; Rankin, Robert L. (2001). "Siouan languages". In DeMaille, Raymond J.; Sturtevant, William C. (eds.). Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 13: Plains. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 94–114.

- ^ a b c Parks, Douglas R.; DeMallie, Raymond J. (1992). "Sioux, Assiniboine, and Stoney Dialects: A Classification". Anthropological Linguistics. 34 (1/4): 233–255. JSTOR 30028376.

- ^ a b Taylor, Alan R. (1981). "Variation in Canadian Assiniboine". Siouan and Caddoan Linguistics Newsletter.

- ^ a b Ullrich, Jan (2008). New Lakota Dictionary (Incorporating the Dakota Dialects of Yankton-Yanktonai and Santee-Sisseton). Lakota Language Consortium. pp. 2, 4. ISBN 978-0-9761082-9-0.

- ^ Andersen, Raoul R. (1968). An inquiry into the political and economic structures of the Alexis band of Wood Stoney Indians, 1880-1964 (PhD dissertation). Columbia: University of Missouri.

- ^ a b c Cook, Eung-Do; Owens, Camille C. (1991). "Conservative and innovative features in Alexis Stoney". Papers from the American Indian Languages Conferences Held at the University of California, Santa Cruz, July and August 1991. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University. pp. 135–146.

- ^ DeMallie, Raymond; Miller, David Reed (2001). "Assiniboine". In DeMaille, Raymond J.; Sturtevant, William C. (eds.). Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 13: Plains. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 572–595.

- ^ a b c d Erdman, Corrie Lee Rhyasen (1997). Stress in Stoney (MA thesis). Calgary: University of Calgary.

- ^ a b Bellam, Ernest Jay (1975). Studies in Stoney phonology and morphology (MA thesis). Calgary: University of Calgary.