Mr. & Mrs. Bridge

| Mr. & Mrs. Bridge | |

|---|---|

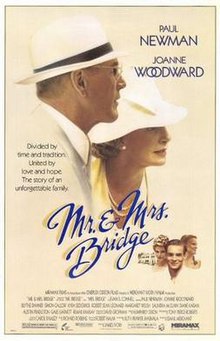

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | James Ivory |

| Screenplay by | Ruth Prawer Jhabvala |

| Based on | Mr. Bridge by Evan S. Connell Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell |

| Produced by | Ismail Merchant |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Tony Pierce-Roberts |

| Edited by | Humphrey Dixon |

| Music by | Richard Robbins (score) Jacques Offenbach (themes Barcarolle and Can Can) |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates | September 1990 (Venice)

|

Running time | 126 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $7.2 million[2] |

| Box office | $7.7 million[3] |

Mr. & Mrs. Bridge is a 1990 American drama film based on the novels Mr. Bridge and Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell. It is directed by James Ivory, with a screenplay by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, and produced by Ismail Merchant.

The film stars real-life couple Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward as the title characters. The character of Mrs. Bridge is based on Connell's mother, Ruth Connell.[4]

Plot

[edit]The film tells the story of a traditionally-minded family living in the Country Club District of Kansas City, Missouri, during the 1930s and 1940s. The Bridges grapple with changing mores and expectations. Mr. Bridge is a lawyer who resists his children's rebellion against the conservative values that he holds dear. Mrs. Bridge labors to maintain a Pollyanna view of the world, against her husband's emotional distance and her children's eagerness to adopt a world view more modern than her own.

Cast

[edit]- Paul Newman as Walter Gene Bridge

- Joanne Woodward as India Bridge

- Margaret Welsh as Carolyn Bridge, Walter and India's daughter

- Kyra Sedgwick as Ruth Bridge, Walter and India's daughter

- Robert Sean Leonard as Douglas Bridge, Walter and India's son

- Simon Callow as Dr. Alex Sauer, psychiatrist

- Remak Ramsay as Virgil Barron, Grace's husband

- Blythe Danner as Grace Barron, India's best friend

- Austin Pendleton as Mr. Gadbury, India's art instructor

- Gale Garnett as Mabel Ong, India's friend

- Saundra McClain as Harriet Rogers, the Bridges' maid

- Diane Kagan as Julia, Walter's secretary

- Robyn Rosenfeld as Genevieve, Dr. Sauer's girlfriend

- Marcus Giamatti as Gil Davis, Carolyn's husband

- Melissa Newman as Young India at the pool

- Salvatore Licata as Young Child

Production

[edit]Joanne Woodward read the first of Mr. Connell's two novels when it was published in 1959, and for many years, she hoped to adapt it into a television production. Originally, she did not intend to play the character of Mrs. Bridge due to the difference in age, but by the late 1980s, when developing the project proved difficult, that was no longer the case.[5]

After a dinner James Ivory first met the Newmans at, they decided to adapt the books into a feature-length film. After a script was finished, Paul Newman agreed to play Mr. Bridge, which brought in enough financing to shoot the film.[6]

Estimated at $7.5 million, with $500,000 immediately earmarked on interest payments for loans, it was considered a very modest budget, but it also granted Merchant and Ivory the freedom to make the film as they wished. The entire crew took very low salaries, while Newman and Woodward both took much lower salaries than to which they were accustomed.[6]

With the exception of a scene in Paris and another that took advantage of an Ottawa snowfall, the film was shot entirely in Kansas City, Missouri, on the same streets that Connell would have traveled as a child and teenager.[7] No sound stages were used as real houses, auditoriums and office buildings were all used as sets.[6] The residence used as the Bridges' home is just a block west of Loose Park on W. 54th St. There is also a scene set in the vault of the old First National Bank (now the Central Library); the same vault has been repurposed as the Stanley H. Durwood Film Vault.[7]

Much of the film was shot out of sequence to save money. For example, when filming the law office of Mr. Bridge over a single morning, the furniture and Newman's makeup and clothes were changed every hour, as the scenes jumped through spring 1932, autumn 1938, winter 1945, and summer 1938.[6]

Budget constraints also prevented the art department from renting their set dressings, forcing them to rely on loans and donations. Brunschwig & Fils[who?] donated $100,000 worth of fabrics and wallpaper, Glen Raven Mills of North Carolina[who?] donated period awning material, and Benjamin Moore donated 100 gallons of paint. A local law firm lent a dozen Tiffany lamps and paintings by Kansas City artists of the 1930s. Merchant borrowed bridge tables from a local society woman and a desk used by the founder of Hallmark from his son, who was the head of the company at the time.[6]

According to production designer David Gropman, the Bridges' home was filled with the personal belongings of the Connell family, with Evan Connell's sister, Barbara Zimmermann, lending all of her porcelain, her whole collection of silver, Christmas tree ornaments, and coffee urn. A lamp that Evan Connell made as a boy can be seen in Douglas Bridge's bedroom, while marble bookends that used to belong to his father were used to dress Mr. Bridge's law office.[6]

Costume designer Carol Ramsey also had to borrow the production's entire wardrobe, including $4,000 of sashes, merit badges, handcarved neckerchief slides and Boy Scout pins from 1938 for Douglas Bridge's Eagle Scout ceremony. The London tailors Gieves & Hawkes agreed to make the entire wardrobe for the film's male characters in return for a screen credit.[6]

A native of Klamath Falls, Oregon, Ivory would tell The New York Times: "The world of Mr. and Mrs. Bridge is the world I grew up in...It's the only film I've ever made that was about my own childhood and adolescence. When we talked about it, that seemed true of Paul and Joanne, too. We talked a lot about manners, about the way things used to be done."[6]

When Ivory was honored by the Houston Cinema Arts Festival in 2014, he presented the film as a personal favorite, adding that it was the one film that he would most like to see reappraised: "It had a wonderful story, great script and fabulous acting. So the fact that it was not as well received as some of the others was disappointing. Maybe there is something inherently depressing for Americans to think about, to look carefully at Mr. and Mrs. Bridge. When it was released we had focus groups after the film. And there was a gap of at least a couple of generations between the audiences and the family Connell had written about. People couldn't understand why Mrs. Bridges was acting the way she did, because they didn't know what American life was like in the 1930s and '40s."[8]

Reception

[edit]Jonathan Rosenbaum of The Chicago Reader wrote, "I'm not much of a James Ivory fan, but this 1990 adaptation of Evan S. Connell's novels deserves to be seen and cherished for at least a couple of reasons: first for Joanne Woodward's exquisitely multilayered and nuanced performance, and second for screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's retention of much of the episodic, short-chapter form of the books. It's true that she and Ivory have toned down many of the darker aspects, but as [The Village Voice] critic Georgia Brown has suggested, Woodward's humanization of her character actually improves on the original. Connell's imagination and compassion regarding this character have their limits, and Woodward triumphantly exceeds them."[9]

Vincent Canby of The New York Times praised the film, calling it "a vigorous, witty, satiric attempt to give dramatic shape to two aggressively anti-dramatic prose works". He also commended Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward for "the most adventurous, most stringent performances of their careers", observing that "there is a reserve, humor and desperation in their characterizations that enrich the very self-conscious flatness of the narrative terrain around them".[10]

Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a rating of 82%, based on 17 reviews.[11]

Awards and nominations

[edit]| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[12] | Best Actress | Joanne Woodward | Nominated |

| Chicago Film Critics Association Awards[13] | Best Actress | Nominated | |

| David di Donatello Awards | Best Foreign Actress | Nominated | |

| Golden Globe Awards[14] | Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama | Nominated | |

| Independent Spirit Awards[15] | Best Female Lead | Nominated | |

| Kansas City Film Critics Circle Awards[16] | Best Actress | Won | |

| Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards[17] | Best Actress | Runner-up | |

| National Board of Review Awards[18] | Top Ten Films | 8th Place | |

| National Society of Film Critics Awards[19] | Best Actress | Joanne Woodward | 2nd Place |

| New York Film Critics Circle Awards[20] | Best Film | Runner-up | |

| Best Actress | Joanne Woodward | Won | |

| Best Screenplay | Ruth Prawer Jhabvala | Won | |

| Venice Film Festival[21] | Golden Lion | James Ivory | Nominated |

| Golden Ciak (Best Film) | Won | ||

| Pasinetti Award (Best Film) | Won | ||

References

[edit]- ^ "Mr. & Mrs. Bridge (1990)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved June 24, 2023.

- ^ "Merchant Ivory Productions Budget vs US Gross 1986-96". Screen International. September 13, 1996. p. 19.

- ^ "Mr. & Mrs. Bridge". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- ^ Sieff, Gemma. "A Visit with Evan Connell". The Paris Review. Spring 2014 (208). Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- ^ Rohter, Larry (November 18, 1990). "Crossing the Bridges With the Newmans". The New York Times. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Harmetz, Aljean (February 18, 1990). "Partnerships Make a Movie". The New York Times. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ a b "Program Notes: Mr. and Mrs. Bridge (1990)". kclibrary.org. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ Evans, Everett (November 8, 2014). "Festival salutes the literate cinema of James Ivory". houstonchronicle.com. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan. "Mr. & Mrs. Bridge". chicagoreader.com. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (November 23, 1990). "A Placid Marriage, And Undercurrents". chicagoreader.com. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ "Mr. & Mrs. Bridge". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ "The 63rd Academy Awards (1991) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on October 20, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ "1988-2013 Award Winner Archives". Chicago Film Critics Association. January 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "Mr. & Mrs. Bridge – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "36 Years of Nominees and Winners" (PDF). Independent Spirit Awards. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ "KCFCC Award Winners – 1990-99". kcfcc.org. December 14, 2013. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "The 16th Annual Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards". Los Angeles Film Critics Association. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "1990 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Past Awards". National Society of Film Critics. December 19, 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "1990 New York Film Critics Circle Awards". New York Film Critics Circle. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ Kennedy, Harlan (1990). "Venice 1990 – The 47th Venice Film Festival". Film Comment. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

External links

[edit]- 1990 films

- 1990 drama films

- 1990 independent films

- American drama films

- Films directed by James Ivory

- Films set in Missouri

- Films set in Kansas City, Missouri

- Films shot in Missouri

- Films set in the 1930s

- Films set in the 1940s

- Films based on American novels

- Merchant Ivory Productions films

- Films with screenplays by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

- Films shot in Ottawa

- Alliance Atlantis films

- Films based on multiple works

- 1990s American films

- 1990s English-language films

- English-language drama films

- Films scored by Richard Robbins

- English-language independent films